Knowledge Integration in the Politics and Policy of Rapid Transitions to Net Zero Carbon: A Typology and Mapping Method for Climate Actors in the UK

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Existing Typologies of Environmental Policy Actors

- (a)

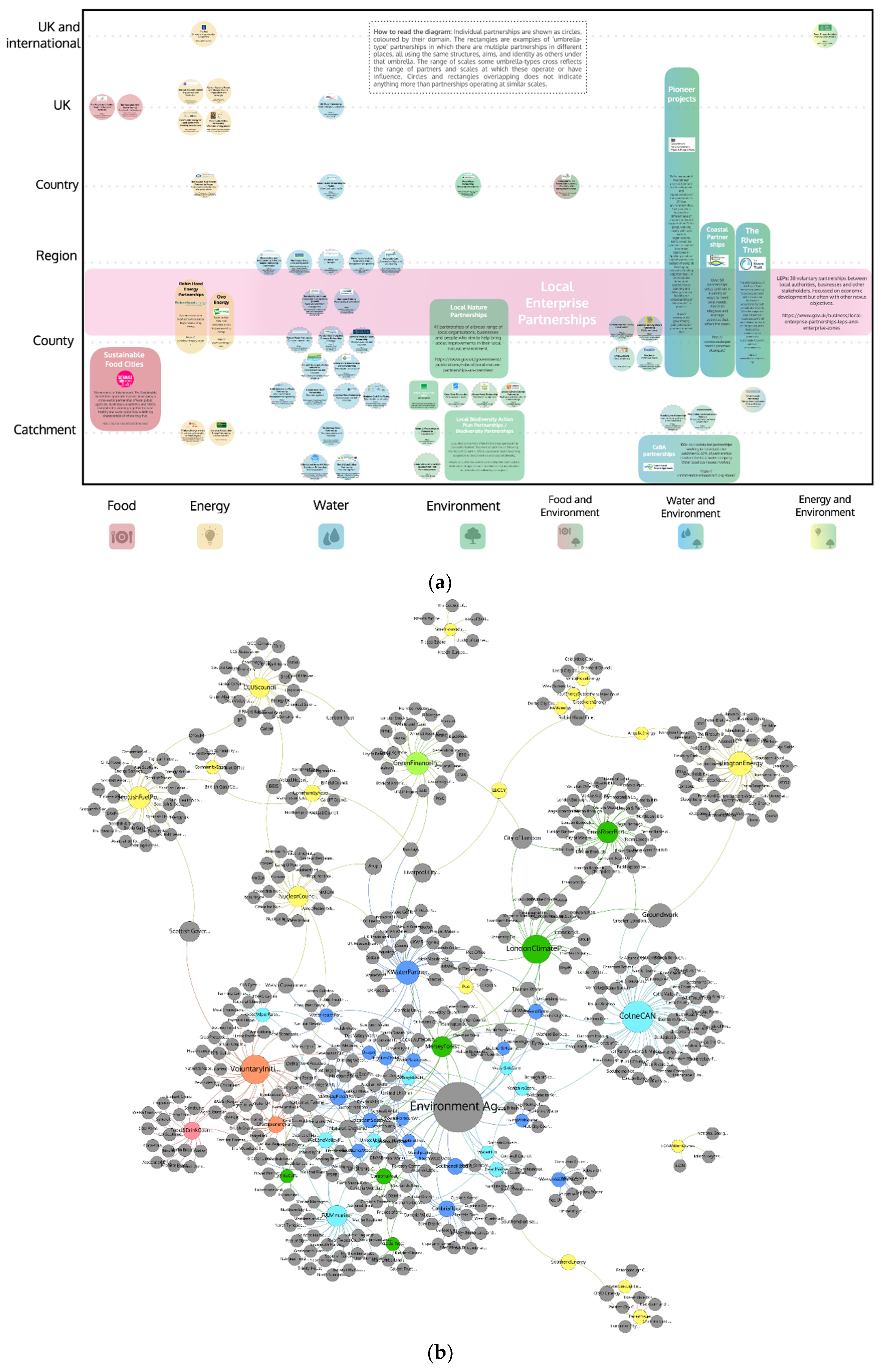

- Scale: Barbrook-Johnson [19] categorised UK organisations involved in public–private partnerships in the food–energy–water–environment nexus by their geographical scale of operation at the catchment, county, regional, devolved nation, UK, or international levels;

- (b)

- Policy discourse: the categorisation of policy discourses in climate change politics helps to understand how issues are framed and how policy discourses relate to each other in terms of aligning/competing groups [20,21,22]. Hess [23] argued that a focus on language and discourse coalitions, rather than on shared core beliefs or identities [24,25], offered greater flexibility in understanding the dynamics of coalitions, for which the goals and compositions may change in response to persuasive counter-framing, new information, events, changes in administration, membership, and institutional form [26] (This point is reiterated below when considering the advantages and disadvantages of various mapping methodologies). Boehnert [27] categorised UK, US, and Canadian actors via five policy discourses: climate science, climate justice, ecological modernisation, neoliberalism, and climate contrarianism.

- (c)

- Organisation type: Costoya [28] proposed a four-part typology of civil society actors based on their organisation, vision of civil society, and logic of social action: (1) Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), (2) social movements, (3) networks, and (4) plateaus. Networks and plateaus were viewed as information-age correlates of the more traditional NGOs and social movements. This typology is summarised in Table 1, column A. Boehnert [27] differentiated actors into 12 types: governments, intergovernmental organisations, science research institutions, media organisations, non-governmental organisations/charities, associations and societies, climate research institutes and think tanks, websites/blogs, contrarian blogs, contrarian organisations, individuals, and corporations.

- (d)

- Sector: various typologies arrange stakeholders into the sector of the economy in which they operate, as summarised in Table 1, column B. The following are examples:

- The UK’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC) publishes “indicator frameworks” for seven sectors of the economy—power, buildings, industry, transport, agriculture and land-use, land-use change and forestry, waste, and F-gases [29].

- Scoones et al. [30] discussed the importance of non-state actors in business, finance, academia, grassroots, and social movements. According to Sovacool and Geels [31], actors also include households, businesses, policymakers, social movements, scientists, journalists, investors, and special interest groups.

- Oxfam International’s [32] guidelines for analysing social and political change processes list social movements, political parties, political and business elites, the military, police, inspirational leaders, and faith leaders as agents of change.

- Climate Assembly UK [33] included an advisory panel representing academic research, think tanks, business associations, environmental organisations, citizen organisations, and trade unions.

- Boehnert [27] mapped various types of media organisations in three categories: journals, newspapers, and television broadcasters; websites; and contrarian blogs.

- (e)

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| Organisation Type/Structure [28] | Sector of Society [27,29,30,31] | Method/Modus Operandi [34,36,37] |

| Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) (e.g., WWF, Friends of the Earth Business associations Trade Unions Think Tanks) Social Movement (e.g., 350.org, School Strike 4 Climate, Extinction Rebellion) Network (e.g., Climate Action Network; Global Climate Forum Transition Towns) Plateau (e.g., World Social Forum) | Academia The Arts Business Citizen NVDA Energy Generation Farming Finance Health Law/Litigation Local Politics Media National Politics Prefigurative Movements Religion Trade Unions Transport | Traditional Methods: Demonstrate Strike Occupy public/private space Donate/subscribe Petition Lobby Public Meeting Boycott Exhibition Theatrical Performance Artwork Civil Disobedience Policy Advocacy Disinformation/astroturfing Recent Methods: Litigate (as Plaintiff) Strike from School Internet-based Calls to Action Divest/Reinvest Digital Media Influencing Prefigurative Politics |

1.2. Existing Organigrams and Maps

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Scope

2.2. Methods

2.3. Method for Typology Design

- Name (actor label): name of the organisation;

- Scale (y-axis): the scales used in this typology are (1) district, (2) region/county, (3) devolved nation, (4) United Kingdom (includes international organisations with a UK office), and (5) international (without a UK office). This scaling corresponds to the administrative areas derived from the Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics [49] (Table 2).

- Net-zero ambition (x-axis): the wider research project that generated this study is focused on the UK net zero carbon policy. Data collected for this paper was similarly restricted to actors’ net-zero policy preferences for the UK as a whole. It is worth noting that some scholars and campaigners have criticised the entire “net-zero” approach, arguing instead for more stringent “absolute zero” emissions targets. Others advocate separate accounting practices for positive and negative emissions. It is also worth noting that net-zero GHG targets are not strictly comparable using only the stated year, since long-term cumulative GHG budgets depend on other factors, including the mitigation pathway (convex, concave, and linear pathways imply different overall GHG emissions); the emissions “scope” (usually referred to as scopes 1, 2, and 3), which specifies the boundary between what is counted and what is omitted; and the reliance on international offsetting and other negative emissions schemes. In addition, some actors specify their UK net-zero policy preference over a range of years, such as “well before 2050” or “by the late 2030s”. The net-zero targets should therefore be viewed as broad approximations of actors’ degrees of urgency/ambition, providing useful insights in terms of alignments and tensions within and between economic sectors, GHG mitigation sectors, policy discourses, and other category data. For these reasons, net-zero ambition is designated in ranges from 2025–2030, 2031–2035, 2036–2040, 2041–2045, 2046–2055, and >2055;

- Policy discourse (actor colour): primary data collected from forty-seven expert interviewees, conferences, workshops, and other transcribed sources, together with secondary material from organisation webpages, reports, journals, and other media, were subjected to thematic analysis [50]. Key themes were developed into an analytical hierarchy—iterating between data management, descriptive accounts, and explanatory accounts—designed to build a conceptual “scaffolding” of broader meanings [51]. The initial reading of the data was literal, and the initial labelling and thematic framework was descriptive or semantic [52]. Thematic analysis of the policy discourses identified in this study (to be detailed in a forthcoming paper) resulted in the following five categories, each of which were allocated a colour in the non-state actors map:

- Revolution (red): this represents actors proposing (quasi-) revolutionary, as opposed to reformist, solutions to the climate crisis. According to these actors, the current capital and elite-controlled system of government is incapable of adequate reform, necessitating system overthrow;

- Participation (yellow): this discourse prioritises democratic participation and collective decisions on targets, pathways, and solutions in the transition to a low-carbon society. “Participation” actors are therefore not assigned to “a priori” net-zero targets;

- Limits (green): this discourse gives primacy to the biophysical capacities and social foundations of a sustainable future. This is a post-growth policy discourse. It points out that infinite economic growth on a finite planet is not possible; moreover, beyond a threshold level of income, it bears little relation to what people really value;

- Growth (blue): this is the nationally and globally dominant policy discourse. It argues that the transition to a low-carbon economy is either compatible with or requires continued GDP growth;

- Delay (purple): this discourse dismisses decarbonisation as a policy priority. Proponents tend to be connected to the fossil fuel industry and/or to an economic libertarian ideology that opposes government intervention.

- Relative influence (non-state actor size): six units of measurement were used in different combinations to calculate non-state actor influence on policy, depending on the social movement or NGO sector and data availability: Alexa Rank 90 Day Trend (https://www.alexa.com/siteinfo); Twitter following (https://twitter.com); revenue (https://www.influencewatch.org; https://beta.charitycommission.gov.uk; https://suite.endole.co.uk); number of MPs (https://members.parliament.uk); readership (https://www.newsworks.org.uk; organisation webpages); and think-tank ranking [53]. As in Boehnert [27], a degree of subjective judgement was used but was further refined by commentary from an informal expert review panel (see Acknowledgements). It was not possible to compare actors across sectors. All calculations were standardised as a percentage of the highest score (or in the case of Alexa Rank, the lowest score) of actors within each sector. The average total score for each actor was used as the final object diameter (from 1–100 units) for fourteen NGO sectors, social movements, and individuals, totalling sixteen non-state sectors. Each of these populates a single row in the whole UK section of the map of non-state actors. State actors were not sized by “relative influence”.

- Policy insider/outsider: Newell [54] and Piggot [55] differentiated “insider” individuals and organisations, who typically provide advice and/or research to government for policy development, from “outsider” individuals and organisations, who tend to be excluded from the policy process. Insider/outsider status is a strong indicator of an organisation’s methods (item 9): outsiders are more likely to use protest tactics whereas insiders tend to use lobbying, advocacy, and research. It is also an indicator of policy radicalness: insiders are less inclined to push for more radical policies [55]. Insider/outsider status is closely associated with but not identical to relative influence (item 5). The most interesting individuals and organisations for those committed to more rapid decarbonisation are the exceptional “radical insiders”: those with privileged access who push for more radical policy [56]. Unsurprisingly, insiders tend to influence policy more than outsiders, but there are contexts in which outsiders can rapidly affect change, a recent example being the Black Lives Matter movement [57,58]. Where coalitions formally invite a broad range of insiders and outsiders to achieve a common goal, for example, the IPPR’s Environmental Justice Commission, the insider/outsider distinction may become otiose. The existence of a diverse “ecology” of insider and outsider NGOs and social movements may also provide strategic benefits: for example, the outsider tactics of Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion may make it impossible to for them to build direct relationships with powerful incumbents in the government, business, or finance. However, if accompanied by sufficient media attention and public sympathy/outrage, they may force these incumbents to raise their ambition and seek alliances with insider organisations and coalitions such as WWF or We Mean Business.

- Actor type (actor shape): actors are divided into non-state actors and state actors. Non-state actors are subdivided into non-governmental organisations (NGOs, circle); NGO networks (circle with border circles); social movements (triangle); movements of movements (triangle within a triangle), which are alignments of social movements; and individuals (star). State actors (rectangle) are subdivided into the UK government (department, select committee, all-party parliamentary group, and statutory body) devolved nation, region/county and district, and intergovernmental organisations. It is important to note that, following Costoya [28], our definition of “NGO” is more expansive and literal than is customary. We use NGO here as a label for all non-state actors that are organisations as opposed to social movements (Table 3, column 7).

- Actor sector: we categorised actors according to the GHG mitigation sector in which they are engaged, broadly following the UK Committee on Climate Change’s “outcome indicators”—all sectors, agriculture, buildings, GHG removal, f-gases, industry, land use, forestry, energy, transport, and waste [29,59]. For the NGO sector, we assigned NGOs to one of fourteen sectors that best describes their primary source of income, membership, or support—the arts, business/professions, citizens, community/city, environment, finance, health, law/litigation, media, political parties, religions, research (academic), research (think tank), and trade unions [27,60,61];

- Modus operandi: actors employ various methods, tactics, and performances to further their aims [62]. The inclusion of modus operandi creates a richer description of each actor and may reveal patterns, strategic links, and informal alignments of actors adopting similar tactics. One example is the small but growing set of professional associations that have recently made “declarations of climate emergency”, some of which include commitments to avoid projects that would increase the burning of fossil fuels, including airport expansion schemes. The list of methods is presented in Table 3, column 9;

- Political discourse: in addition to policy discourses (item 4), this typology categorises political discourses used to motivate and persuade the public and other actors to support their cause, shaping “how we see and imagine problems and solutions, and how we come to define, know, and frame futures” [30] (p. 21). Political discourses are divided into grand narratives, counter-narratives, and motivational frames. Grand narratives are defined as compelling, unifying stories for rapid transition to a more sustainable future, based on themes such as restoration, redemption, and emergence [63,64,65,66,67]; counter-narratives are discourses designed to delay decarbonisation and concerted action on climate change. We reproduced Lamb et al.’s [68] list of twelve delay discourses, grouped into four overall delay strategies. Motivational Frames can be used by any actor to encourage or discourage action on climate change. The motivating efficacy of political discourses depends on many factors, including recipients’ values, social identity [69,70], and the perceived trustworthiness of messengers [71]. Political messaging is therefore often tailored to appeal to specific contexts and audiences.

2.4. Design Method for the State Actor Organigram and Non-State Actor Map

- “net-zero ambition” for the UK as a whole: along the x-axis in columns separated by dotted lines. Actors in the same column (e.g., 2046–2055) share the same range of UK net-zero ambition, regardless of their location from the left to the right of the column; the left–right sortition of actors within the same row and column reflects only their influence relative to other actors in that row and column, as explained in “relative influence” below;

- “policy discourse”, as indicated by the actor’s colour (Figure 8 legend). Note that, for the “participation” discourse (yellow), several actors may collectively occupy the same object, stretched across several columns of net-zero ambition. This illustrates the priority of this discourse to encourage public participation and deliberative decision-making rather than to rely on top-down targets and solutions;

- “relative influence”. Actors within the same sector (single row) were sized according to a standardised average of relative quantitative measures of “relative influence” (from 1–100), together with a degree of judgement and external expert review. The layout of actors within each sector (single row) of the map follows a two-stage sorting process. The first stage sorts all actors within each sector by relative influence from left (low influence) to right (high influence); a second stage then re-positions each actor in the row according to their range of net-zero ambition (e.g., 2025–2030, 2031–2035, etc). Actor size remains unchanged, but the left–right sortition is now only maintained within each column of net-zero ambition. It is therefore possible to have a larger-sized (highly influential) actor placed to the left of a smaller one, but only if that larger actor occupies an earlier, more ambitious range of net-zero ambition.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- actors and scales, from the international to local levels or within a single organisation;

- actors within any mitigation sector or a combination of sectors (e.g., buildings or transport);

- actors within any NGO sector or a combination of NGO sectors (e.g., finance or political parties);

- policy targets (e.g., actors’ own individual targets, industry-wide targets, or regional targets); and

- policy discourses, political discourses, or advocacy methods.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; IPBES Secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/biodiversity/pdfs/Summary-for-Policymakers-IPBES-Global-Assessment.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Global Warming of 1.5 °C Special Report; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; World Meteorological Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. In Proceedings of the 21st Paris Climate Change Conference, Paris, France, 12 December 2015; Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/9064 (accessed on 6 April 2016).

- Figueres, C.; Rivett-Carnac, T. The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis; Manila Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Transparency, 2018. Brown to Green: The G20 Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy. Available online: www.climate-transparency.org/g20-climate-performance/g20report2018 (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Overland, I.; Sovacool, B.K. The Misallocation of Climate Research Funding. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillion, D.Q. The Loud Minority: Why Protests Matter in American Democracy; Princeton University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. 2019. Available online: https://transitionsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/STRN_Research_Agenda_2019c-2.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2019).

- Roberts, C.; Geels, F.W.; Lockwood, M.; Newell, P.; Schmitz, H.; Turnheim, B.; Jordan, A. The Politics of Accelerating Low-Carbon Transitions: Towards a New Research Agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 44, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J. Energy Democracy and Social Movements: A Multi-Coalition Perspective on the Politics of Sustainability Transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Broderick, J.F.; Stoddard, I. A factor of two: How the mitigation plans of climate progressive nations fall far short of Paris-compliant pathways. Clim. Policy 2020, 20, 1290–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Zero Carbon Sooner—The Case for an Early Zero Carbon Target for the UK; CUSP Working Paper No. 18; University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.cusp.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP18-Zero-carbon-sooner.pdf/ (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- OECD. Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach, New Approaches to Economic Challenges; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J.; Kallis, G. Is Green Growth Possible? New Polit. Econ. 2020, 25, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknost, D.; Hammond, M. Beyond the Environmental State? The political prospects of a sustainability transformation. Environ. Polit. 2020, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebeck, K.; Williams, J. The Economics of Arrival: Ideas for a Grown-Up Economy; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity without Growth, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics; Penguin: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barbrook-Johnson, P. Innovative Partnerships: A Review of Innovative Public-Private Partnerships in Food-Energy-Water-Environment Domains in the UK. CECAN Report. 2019. Available online: www.cecan.ac.uk/resources (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Hajer, M.A.; Versteeg, W. Voices of Vulnerability: The Reconfiguration of Policy Discourses. In The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society; Drysek, J.S., Norgaard, R.B., Schlosberg, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A. The Politics of Environmental Discourse: Ecological Modernisation and the Policy Process. Oxford Scholarship Online. 1997. Available online: https://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/019829333X.001.0001/acprof-9780198293330 (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- Entman, R. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J. Coalitions, framing, and the politics of energy transitions: Local democracy and community choice in California. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 50, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.A. The advocacy Coalition Framework: Revisions and relevance for Europe. J. Eur. Public Policy 1998, 5, 98–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; McAdam, D. A Theory of Fields; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.; Sovacool, B.K. Energy Democracy, Dissent and Discourse in the Party Politics of Shale Gas in the United Kingdom. Environ. Polit. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boehnert, J. Mapping Climate Communication. Poster Summary Report. 2014. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2021767/Mapping_Climate_Communication_Poster_Summary_Report (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Costoya, M.M. Toward a Typology of Civil. Society Actors: The Case of the Movement to Change International Trade Rules and Barriers; Civil. Society and Social Movements Programme Paper Number 30; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: http://www.unrisd.org/80256B3C005BCCF9/httpNetITFramePDF?ReadForm&parentunid=0451352E376C1031C12573A60044CE42&parentdoctype=paper&netitpath=80256B3C005BCCF9/(httpAuxPages)/0451352E376C1031C12 (accessed on 24 June 2018).

- Committee on Climate Change (CCC). Reducing UK Emissions. 2018 Progress Report to Parliament. 2018. Available online: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/reducing-uk-emissions-2018-progress-report-to-parliament/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Scoones, I.; Newell, P.; Leach, M. The Politics of Green Transformations. In The Politics of Green Transformations; Scoones, I., Leach, M., Newell, P., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.J.; Geels, F.W. Further Reflections on the temporality of energy transitions: A response to critics. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxfam International. How to Analyse Change Processes; Research Guidelines: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/how-to-analyse-change-processes-620866 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Climate Assembly UK. Advisory Panel. 2020. Available online: https://www.climateassembly.uk/detail/advisorypanel/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Tarrow, S. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.; Sandler, J.; Kelleher, D.; Miller, C. Gender at Work: Theory and Practice in 21st Century Organisations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Raekstad, P.; Gradin, S.S. Prefigurative Politics: Building Tomorrow Today; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming; Bloomsbury Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turnberry, J.; Haxeltine, A.; Lorenzoni, I.; O’Roprdan, T.; Jones, M. Mapping Actors Involved in Climate Change Policy Networks in the UK. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, 2005. Working Paper 66. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.111.6089&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Willis, R.; Mitchell, C.; Hoggett, R.; Britton, J.; Poulter, H. Enabling the Transformation of the Energy System: Recommendations from IGov; EPSRC/University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2019; Available online: https://projects.exeter.ac.uk/igov/enabling-the-transformation-of-the-energy-system/ (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Bäckstrand, K.; Kuyper, J.W.; Linnér, B.; Loövbrand, E. Non-state actors in global climate governance: From Copenhagen to Paris and beyond. Environ. Polit. 2017, 26, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernstein, S.; Hoffman, M. The politics of decarbonization and the catalytic impact of subnational climate experiments. Policy Sci. 2018, 51, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hess, D.J. Sustainability Transitions: A political coalition perspective. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pacheco-Vega, R.; Murdie, A. When do environmental NGOs work? A test of the conditional effectiveness of environmental advocacy. Environ. Polit. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. Too Hot to Handle? The Democratic Challenge of Climate Change; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, J.I.; Hadden, J. Exploring the framing power of NGOs in global climate politics. Environ. Polit. 2017, 26, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D. How Change Happens; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, P. Towards a Global Political Economy of Transition: A Comment on the Transitions Research Agenda. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 34, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Andonova, L.B.; Betsill, M.M.; Compagnon, D.; Hale, T.; Hoffmann, M.J.; Newell, P.; Paterson, M.; VanDeveer, S.D.; Roger, C. Transnational Climate Change Governance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ONS. All Administrative Names and Codes in the United Kingdom; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2020. Available online: https://geoportal.statistics.gov.uk/search?collection=Dataset&sort=name&tags=all(NAC_ADM) (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigour using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L.; O’Connor, W. Carrying Out Qualitative Analysis. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003; pp. 219–262. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGann, J.G. 2019 Global Go to Think Tank Index Report; TTCSP Global Go to Think Tank Index Reports; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/think_tanks/17 (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Newell, P. Climate for change? Civil society and the politics of global warming. In Global Civil Society Yearbook; Holland, F., Ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005; pp. 90–119. [Google Scholar]

- Piggot, G. The influence of social movements on policies that constrain fossil fuel supply. Clim. Policy 2018, 18, 942–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, R. Building the Political Mandate for Climate Action; The Green Alliance: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.green-alliance.org.uk/resources/Building_a_political_mandate_for_climate_action.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Cohn, N.; Quealy, K. How US Public Opinion Has Moved on Black Lives Matter. The New York Times. 10 June 2020. Available online: https://www.gooriweb.org/news/2000s/2020/nyt10june2020.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Ankel, S. 30 Days That Shook America: Since the Death of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter Movement Has Already Changed the Country. Business Insider. 24 June 2020. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/13-concrete-changes-sparked-by-george-floyd-protests-so-far-2020-6?r=US&IR=T (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Committee on Climate Change (CCC). Net Zero: The UK’s Contribution to Stopping Global Warming. 2019. Available online: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/net-zero-the-uks-contribution-to-stopping-global-warming/ (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- Climate Assembly UK. 2020. Available online: https://www.climateassembly.uk (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Scoones, I.; Leach, M.; Newell, P. (Eds.) The Politics of Green Transformations; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, D.; Diani, M. Social Movements: An Introduction; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bushell, S.; Buisson, G.S.; Workman, M.; Colley, T. Strategic Narratives in Climate Change: Towards a Unifying Narrative to Address the Action Gap on Climate Change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monbiot, G. Out of the Wreckage: A New Politics for an Age of Crisis; Verso: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A. The Myth Gap: What Happens When Evidence and Arguments Aren’t Enough; Eden Project Books: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, P. Journey to Earthland: The Great Transition to Planetary Civilisation; The Tellus Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.greattransition.org/publication/journey-to-earthland (accessed on 15 March 2017).

- Klein, N. This Changes Everything; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, W.F.; Mattioli, G.; Levi, S.; Roberts, J.T.; Capstick, S.; Creutzig, F.; Minx, J.C.; Müller-Hansen, F.; Culhane, T.; Steinberger, J.K. Discourses of climate delay. Glob. Sustain. 2020, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahan, D.M. Fixing the communications failure. Nature 2010, 463, 296–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raven, R.; Kern, F.; Verhees, B.; Smith, A. Niche Construction and Empowerment through Socio-Political Work. A Meta-Analysis of Six Low-Carbon Technology Cases. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2016, 18, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batson, D.C. Altruism in Humans; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vugt, M. Triumph of the Commons. New Sci. 2009, 203, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K.A.; Tost, L.P. The Egoism and Altruism of Intergenerational Behavior. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 13, 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fehr, E.; Gaechter, S. Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbacher, D. What Motivates Us to Care for the Distant Future? In Intergenerational Justice; Gosseries, A., Meyer, L.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 273–300. [Google Scholar]

- Scruton, R. Settling Down and Marking Time; Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.cusp.ac.uk/themes/m/rs_m1-2/ (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- Jonas, H. Imperative of Responsibility: In Search of an Ethic for the Technological Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, P. The Expanding Circle: Ethics, Evolution and Moral Progress; Princeton University Press: Oxford, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.; Kallgren, C.; Reno, R. A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: A theoretical refinement and re-evaluation of the role of norms in human behaviour. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.C. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory; Blackwell Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Laudato Si’. Encyclical Letter Laudato si’ of the Holy Father Francis on Care of Our Common Home; Vatican Press: Vatican City, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Krznaric, R. The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short Term World; W.H. Allen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Christoff, P. Ecological modernisation, ecological modernities. Environ. Polit. 1996, 5, 476–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallis, G. Limits: Why Malthus Was Wrong and Why Environmentalists Should Care; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vivid Economics. Keeping it Cool: How the UK Can End its Contribution to Climate Change. An Analytical Report for WWF. 2018. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/uk-can-lead-way-stopping-climate-change-reaching-net-zero-emissions-2045-new-report-reveals (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Dunlap, R.E.; McCright, A.M. Challenging Climate Change: The Denial Countermovement. In Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 393–442. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Brulle, R.J. Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.R.; Christie, I.; Willis, R. Social Tipping Intervention Strategies for Rapid Decarbonisation Need to Consider How Change Happens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10629–10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centola, D.; Becker, J.; Brackbill, D.; Baronchelli, A. Experimental Evidence For Tipping Points in Social Convention. Science 2018, 360, 1116–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leach, M.; Scoones, I. Mobilising for Green Transformations. In The Politics of Green Transformations; Scoones, I., Leach, M., Newell, P., Eds.; Abingdon: Routledge, UK, 2015; pp. 119–133. [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP). After Protest: Pathways Beyond Mass Mobilization. 2019. Available online: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Youngs_AfterProtest_final2.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Centola, D. How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex. Contagions; Princeton University Press: Woodstock, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crutchfield, L.R. How Change Happens: Why Some Social Movements Succeed While Others Don’t; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, B.; Exley, Z. Rules for Revolutionaries: How Big Organizing Can. Change Everything; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- North, P. The Politics of Climate Activism in the UK: A Social Movement Analysis. Environ. Plan A 2011, 43, 1581–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettifor, A. The Case for the Green New Deal; Verso: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPPR. Faster, Further, Fairer: Putting People at the Heart of Tackling the Climate and Nature Emergency; Interim Report of the IPPR Environmental Justice Commission; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.ippr.org/files/2020-05/faster-further-fairer-ejc-interim-may20.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Cerrato, D.; Ferrando, T. The Financialization of Civil Society Activism: Sustainable Finance, Non-Financial Disclosure and the Shrinking Space for Engagement. Account. Econ. Law A Conviv. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKibben, B. Physics Doesn’t Negotiate: Notes on the Dangerous Difference between Science and Political Science. Medium. 30 August 2015. Available online: https://medium.com/climate-desk/why-the-earth-is-heating-so-fast-267072ab2b49 (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Vadén, T.; Lähde, V.; Majava, A.; Järvensivu, P.; Toivanen, T.; Eronen, J.T. Raising the Bar: On the Type, Size and Timeline of a ‘Successful’ Decoupling. Environ. Polit. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | ||||

| 5 | International | |||

| 4 | United Kingdom | |||

| 3 | England | Scotland | Wales | Northern Ireland |

| 2 | Region/County | Council Area | Principle Area | County |

| 1 | District | District | ||

| 1. Actor Name (label): 2. Scale (y-axis): District, Region/County, Devolved Nation, UK, International 3. Net-Zero Ambition (x-axis): 2025–2030, 2031–2035, 2036–2040, 2041–2045, 2046–2055, 2051–2055, >2055 4. Policy Discourse (colour): Revolution, Participation, Limits, Growth, Delay 5. Relative Influence (size): 6. Policy Insider/Outsider: | ||||

| 7. Actor Type (shape) | 8. Actor Sector | 9. Modus Operandi | 10. Political Discourse | |

| Non-State Actors: NGOs (circle) NGO Networks (circle + circle border) Social Movements (triangle) Movement of Movements (double triangle) Individuals (star) State Actors (all rectangles) UK Government

Regions/Counties Districts Intergovernmental Organisations (IGOs) | Mitigation Sectors: All sectors Agriculture Buildings GHG removal F-Gases Industry Land use, forestry Energy Transport Waste NGO Sectors: The Arts Business/professions Citizens Community/city Environment Finance Health Law/litigation Media Political parties Religions Research/academy Research/think tank Trade unions | Traditional Methods: Art/performance Boycott Civil disobedience Demonstrate/march Divest/reinvest Donate/subscribe Lobby Occupy space Petition Policy advocacy Public meeting Publish Strike Education/training Disinformation Recent Methods Deliberative democracy Digital media campaign Internet call to action Litigation Prefigurative politics Strike from school | Grand Narratives: Emergence Redemption Resilience Restoration Stewardship Survival Utopia Prosperity/wellbeing Counter-Narratives: Redirect Responsibility:

| Motivational Frames Ego +: self-enhancement/co-benefits, legacy, reputation [72,73,74] Ego -: negative emotions, e.g., fear, shame, guilt, outrage, [75] Conserving: conserving goods of natural/capital value: love of land, home, heritage [76,77,78] Altruist: concern for the welfare of others [72] Collectivist: concern for the welfare of a specific group; loyalty; solidarity [72] Principlist: ethics of justice, fairness, humanity, rights, freedom, the greatest good [72,77,79,80] Normative: human tendency to imitate and conform to perceived social norms [81,82] Self-transcendent: a trans-generational cause that extends beyond one’s own limited existence [77,79,83,84] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, S.R.; Christie, I. Knowledge Integration in the Politics and Policy of Rapid Transitions to Net Zero Carbon: A Typology and Mapping Method for Climate Actors in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020662

Smith SR, Christie I. Knowledge Integration in the Politics and Policy of Rapid Transitions to Net Zero Carbon: A Typology and Mapping Method for Climate Actors in the UK. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020662

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Steven R., and Ian Christie. 2021. "Knowledge Integration in the Politics and Policy of Rapid Transitions to Net Zero Carbon: A Typology and Mapping Method for Climate Actors in the UK" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020662

APA StyleSmith, S. R., & Christie, I. (2021). Knowledge Integration in the Politics and Policy of Rapid Transitions to Net Zero Carbon: A Typology and Mapping Method for Climate Actors in the UK. Sustainability, 13(2), 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020662