Abstract

The starting point of the presented research is the theory of destination marketing, in which the concept of destination branding is the key element. Destination branding models include the idea of visual brand identity, which includes the logo as a crucial element. Since the 1980s, the concept of sustainable development has shaped the society and global economy, including tourism. Tourists are increasingly guided by the analysis of the tourist area in terms of the importance of nature and the possibility of spending free time responsibly. They look for a sustainable tourist offer. Therefore, the aim of this work is to evaluate the tourist offers of Polish territorial units in terms of visual message—logo and its content, and to examine whether they comprise design components that reveal the sustainable development of the destination. The research method was content analysis of promotional signs. Sustainable development in tourism focuses on three pillars: nature, responsible tourist activity, and the historical remains protected in a sustainable way. The authors search for such images in the logos. In the conclusion, the authors summarize that elements of nature and historical heritage are strongly present in the logos, which does not mean that the tourist offer is a balanced offer.

1. Introduction

The visual components of the destinations’ brands—signatures of towns and counties (in Polish language—poviats)—were the subjects of the presented research. The authors examined obtainable logos and slogans (obtainable here means practiced in destination branding at the time of the query (from January to the end of June 2020)). The study tries to answer the following research questions:

- What does the destination’s signature communicate the potential tourists?

- How many of these narratives communicate the sustainable development of tourist destinations?

- How is sustainable tourism communicated in promotional signatures?

The novelty of the presented research consists of three related elements. First, the use of a visual analysis method by analyzing the presence of design components which are closely connected with sustainability. In social research, visual methods raise methodological questions [1,2], and although they are used in tourism analysis [3], they still raise doubts in academia. The authors indicate, however, that the subject of research (logo) itself provokes the use of visual analysis, and the method would have to be appropriate—at the same time—for quantitative and qualitative analyses. Secondly, the study also enriches research on destination branding by conducting analyses of Poland as a case study and thirdly applying an interdisciplinary approach—both elements are rare in the literature [4]. The authors endeavored to investigate the relationship between destination branding and sustainability in the visual presentation of the Polish logos. Such an effort has been successfully undertaken in other researches [5], which indicates the theoretical and practical usefulness of such interdisciplinary approaches.

Three main concepts were the starting points for the study: (1) destination branding as a theory of tourist promotion of a place, (2) semiotics and visual semiotics [6] as the methodology of research and (3) sustainable tourism as an industry which ensures the development of local community and natural environment and promotes human welfare and public participation in decision-making [7]. The research mostly focuses on the analysis of visual components of the destination brands. The signature is a visual element of the brand consisting of a logo, slogan and other additional elements such as fonts. It is the structured relationship between a logotype, brandmark, and tagline [8] that in graphic design theory is understood as precisely defined relationships among these elements in terms of proportion, placement, distance, colour, typeface, background control, and non-distortion (misused). As Healey stresses, the conventional solution of symbol plus wordmark is the most common form for a logo, which is expected to have form and colours [9]. The other researchers have stressed that a logo also contains additional elements such as shape [10,11,12] (The authors decided not to take into account the shape (form) of the analyzed logos. There are studies showing that the shape of the logo affects the effectiveness of its impact [10,11]; such attempts were also made in Poland [12]. There was also an attempt at such an analysis with regard to sustainability [13]. However, there are methodological concerns to these studies: they took place in controlled, laboratory conditions, and not in a natural environment, they manipulated the shape and form of the logo (e.g., names were removed, fonts were changed), fictitious logos were used, and the study groups were deliberately selected, not random.).

The aim of this work is to get knowledge about the content of promotional visual signs (signatures) which try to promote the sustainable development of a destination and at the same time, sustainable tourism. To reach such a goal, in the process of examination, the symbols of sustainability in the destination’s signatures were searched for by analysing them, using content analysis as the research method. The authors try to fill the gap in research on destination branding by exploring the issue of what a signature communicates to the audience, considering only one of the contemporary perspectives, such as sustainability.

Knowledge obtained from the study has two aspects: (1) theoretical—the research is aimed to improve the destination branding theory with the communication functions of the visual content of signatures and (2) practical, by indicating the applied guidance resulting from this concept.

Content analysis as a qualitative research method was chosen because it allows for the analysis of logos and slogans contained in the promotional signs. Secondly, considering the theory of destination branding, one may assume that a creator of the territorial signatures wants to disclose some properties important for a place, and he/she chooses such elements which may symbolize the most crucial and typical features of the destination and its community. The results of the research may put a new perspective on understanding the signature’s significance in destination branding. The content analysis method of the research is valued in such an examination because it helps to recognise what the senders (in the case of destination signatures they are local government units—LGU) want to communicate to the receivers—tourists and residents [14].

During the research process, the authors met a practical problem. It was difficult to separate the creator of the signature (an author of the logo and slogan) from the sender (a transmitter of the message contained in the signature). The term ‘creator’ is understood as the graphic designer who carries out a task delegated by the competent administrative authority. The sender is the LGU commissioning a logo for marketing purposes. Therefore, there are consequences that affect the content of the logo. The authors in the previous research [15] concluded that there are three ways to build the visual system of a place in Poland:

- (1)

- Signs are created in offices, i.e., they are made by officials.

- (2)

- The client (in that case the LGU) specifies the requirements for the content of the logo in details, what limits the creativity of the graphic designer.

- (3)

- The signs are subject to stakeholders’ consultation processes (e.g., citizens) that influence the content of the signatures.

Such a variety of signature creation methods has consequences in their content. Some of them express what governors of the territory wish to disclose, some present features which are expected by the governors of the place, however they do not necessarily reflect the specificity (genius loci of the place) of a given destination, and some are created in a long, complex, and relational process [15,16] which has an impact on identity or description of the promoted place.

The literature dealing with the functions of visual identification in tourism promotion is limited [17,18,19], and based mainly on case studies [3].

The present study enriches the existing literature by the semiotic analysis of signatures, with a special interest in symbols of sustainability, marked by the visual identification of places which are aimed to promote tourism in a particular destination. The main objective of the research is therefore to describe the content of the signatures and indicate to what extent this content communicates the sustainable development of a tourist destination. Choosing from the rich literature about the symbols of sustainability, the authors are aware of the limitation of participants’ observations. Considering such a subjective point of view, the researchers wanted to understand the logo phenomena genuinely and in such a way that has an impact on recognizing visual phenomena significance in destination branding.

When examining visual signs, the authors treat them as objects inseparably linked with the entities commissioning the logo creation (officials), and the direct authors, i.e., graphic designers. The research follows a humanistic mode of inquiry developed specifically to address socially constructed phenomena [20] that assumes that the logo (a subject) is strongly associated with the entity that created it (the author). Taking into account the above assumptions, one may conclude that signatures communicate official images of the places, but not the characteristics of the community and the destination itself, which they are supposed to represent. Considering the concept of reception, it is presumed in the presented research that the participants in a social action are the judges of rationality (in the case of logo design they are local governments who are senders) whose judgement is local and necessarily relative. The audience (i.e., prospective tourists in that case) seeks a more universal rational explanation of the signatures’ content and meaning [21] (p. 172).

The structure of the article is as follows:

- Theoretical framework

- Materials and methods

- Results

- Conclusions, including theoretical implications, managerial implications, limitations and future research.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. From Destination Marketing to Destination’s Logo

Destination marketing is a relatively new subject in the professional tourism literature (Pike suggests the following definition of destination marketing: ... the process of matching destination resources with environment opportunities, with the wider interests of society in mind [22] (p. 27). For definitions see also [23].) The first research papers appeared in the 70s, but considerable development occurred at the beginning of the 21st century [24]. The concept of destination branding is even newer—the scientific studies began after 2000 [4, 25, 26]. The first scientific conference on this topic was held in 2005 [22]. However, since then, destination branding has become a legitimate theoretical concept in scientific tourism research. Studies in this field indicate the multidisciplinary nature of the ‘destinations’ phenomenon [27]. It should be added that destination marketing adopts many concepts from so-called ‘universal marketing’. One of them is the idea of brand identity [28,29], and brand identity development, which is understood as the vision of how the destination should be perceived in the marketplace [18,30]. Many previous studies suggested that the abovementioned idea—brand identity—is the key ingredient of a brand [8,31], and—as a consequence—destination brand identity in tourism [30,32,33,34,35,36]. As Zavattaro clearly states: Identity is what brand managers shape and put out to stakeholders via communications tools, landscape design, and other elements of place making [37] (p. 29). All above cited studies indicate that the tangible component of the brand’s identity is its visual identity, as Alina Wheeler states: Brand identity fuels recognition, amplifies differentiation, and makes big ideas and meaning accessible [8] (p. 4). Many studies highlight that brand identity is a prerequisite for successful marketing communication in business as well as in the public sector [38,39]. This also applies to destination brands [40]. An indispensable condition for reliable marketing communication is a coherent identification of the sender—in the case of destination, it is a city, town, community, region, etc., which is why the visual signs (signatures) have a crucial impact. The place brand communicates the particular attributes of that place, and thus it gives the destination its specific meaning [41].

The authors consider a destination the basic analytical unit [22], and try to analyse the logos of destinations considering destination marketing and branding as legitimate research fields. Destination is a geographical space in which a cluster of tourism resources exists, and the tourists actively take advantage of them [18]. In order for this destination to become a tourist attraction, it is necessary to match these resources with the interests of tourists, which is carried out by marketing [18]. However, in view of the multitude of marketing activities, including destination marketing, both in theory and in practice, the need to build a destination brand is emphasized as a unique combination of product characteristics and added values [m]. The comprehensive definition of the destination brand, from both the buyer and seller perspective, is proposed by Blain, Levy, Ritchie [42] (p. 337). This definition incorporates the visual identity of the destination brand:

Destination branding is the set of marketing activities that (1) support the creation of a name, symbol, logo, word mark or other graphics that readily identifies and differentiates a destination; that (2) consistently convey the expectation of a memorable travel experience that is uniquely associated with the destination; that (3) serve to consolidate and reinforce the emotional connection between the visitor and the destination; and that (4) reduce consumer search costs and perceived risk. Collectively, these activities serve to create a destination image that positively influences consumer destination choice.

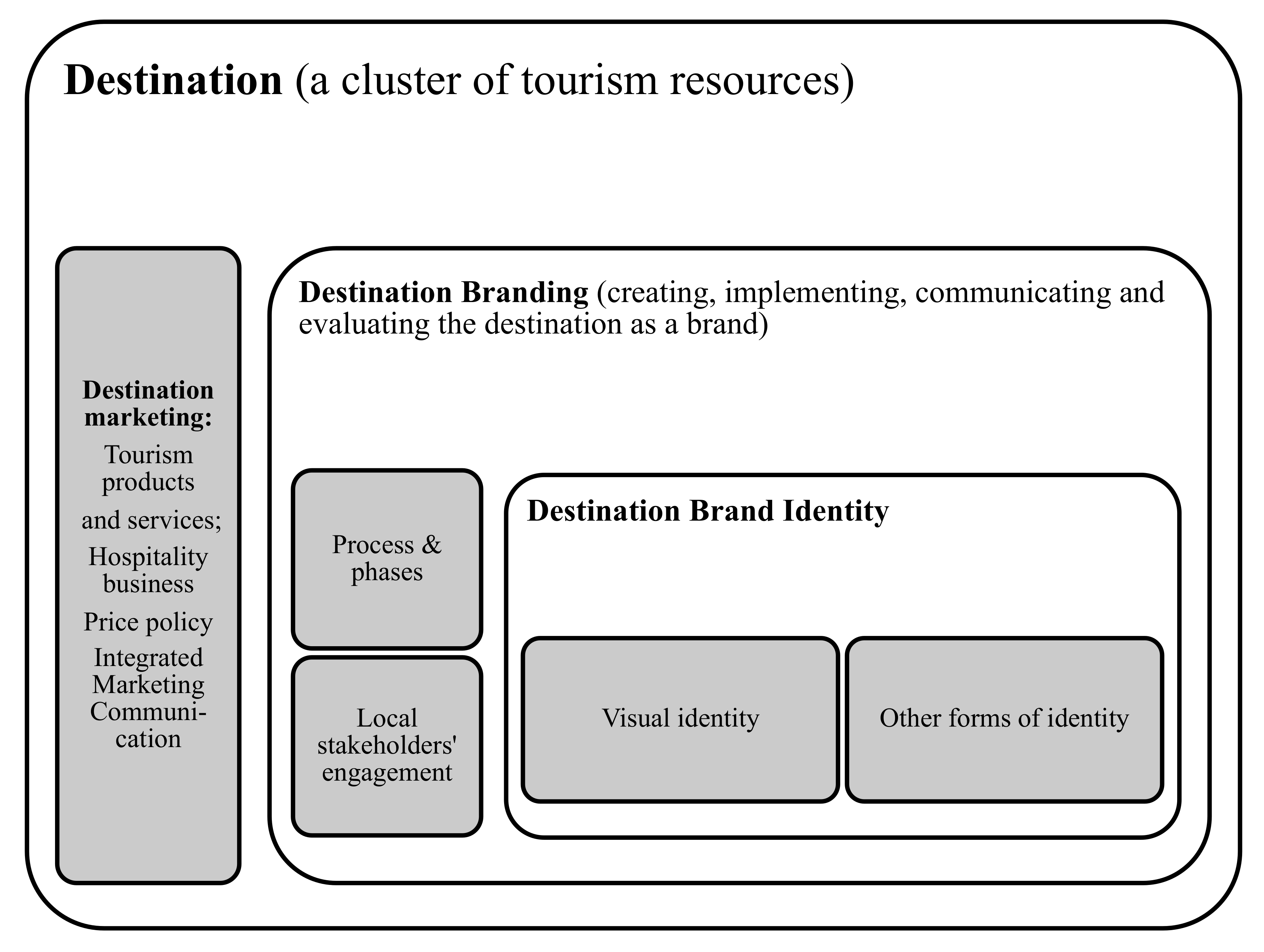

It must be stressed that destination branding is more complex than product or corporate branding, which is why it is so difficult to define a brand message [43]. The process of brand building depends on the destination marketing phases which run in parallel with the brand building process. The content of the destination brand depends on the identity of the place (genius loci) and any kind of symbols important to local stakeholders who are more or less actively involved in the destination branding process. Taking into account the literature on the subject matter and the cited definitions, the authors propose their own analytical model, which is concentrated on the sender’s perspective (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of destination as a marketing invention.

Previous researches of the authors [15,44] illustrate that identity is a key component determining destination marketing and branding. However, examination of the visual identification of places is relatively rare, grounded primarily in single case studies, and the conclusions are not coherent enough [45,46,47,48]. Assuming that identity affects the image and attitudes of tourists towards the destination [22], it seems important to examine the content of identity and—especially—visual identity as significant components of destination brand identity. Following the analysis of Echtner [49], visual signs practiced in the tourism industry not only denote, but also connote the place identity. The author states [49] (p. 49):

That which is a sign (namely, the associative total of a concept and an image) in the first system [i.e., denotative], becomes a mere signifier in the second. Part of the semiological enterprise becomes moving beyond the denotated sign system to the mythical level. Such a layered view of semiotics has particular relevance to the analysis of tourism’s signification systems, with their emphasis on denotation, myth and fantasy.

To sum up, the research approach can be operationalized as an attempt to gain a profounder understanding the connotative meanings hidden under the denotative surface. Visual identity of destination denotates what creators want to reveal and at the same time it connotates, in the light of culturally accepted codes, a particular meaning of the iconic sign which is expected by the authors as a visual form of identity [50] (p. 248). As Eco stresses, the iconic sign refers not to the subject itself, but to its perceptual schema [50] (p. 136). A signature is an iconographic code which connotes the cultural symbols of the destination. Therefore, in such a way, a logo or/and slogan might become an iconic sign that can be reproduced, quoted, or transmitted to the recipients (tourists and residents).

Many logos of Polish destinations refer to the substance (Ger. Substanz), and display what the city/community has to offer to the tourists [51]. It should be added that from the studies on the Polish cases [15,52] two additional conclusions follow: (1) the logos of local government units are also destinations’ logos (creation of separate tourist brands occurs rarely) and (2) these logos are closer to illustrations for clarification than symbols of reality. Logos are stories, illustrations, and narratives, which make them easier to interpret. Studying the logo as a narrative enables extensive content analysis. The logo is a story [51], and thus it is a bearer of history, legends, tales about a place and its inhabitants (community).

2.2. From Sustainability to Sustainable Tourism

There is a systematically growing concern regarding sustainability and sustainable development both in research and business practice. The term sustainable tourism occurred when it was recognised that tourism should be developed in a sustainable manner [53]. Since tourism has a crucial impact on economy, society, and culture, this industry can be a vital factor of sustainability [54].

Tourism can be analysed as an economic activity as well as an element of sustainable development of the particular territory [55]. Sustainable development as an idea emerged in the early 90s when “Journal of Sustainable Tourism” appeared [56].

There are many definitions of sustainable tourism which vary depending on the methodological approach adopted. The concept of sustainable tourism can be interpreted as a process of tourism development [57] and/or an outcome of tourism development [58]. In the classic textbook “Global Tourism”, sustainable tourism is a component of sustainable development, which consists of seven main dimensions: resource management, economic activity, social obligation, aesthetic appeal, ecological parameters, biological diversity, and basic life support system [59] (p. 178–179). The World Tourism Organization defines sustainable tourism as tourism which leads to the management of all resources in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be filled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support systems [60]. As Faulkner [61] stresses, sustainable tourism development is a form of tourism which protects and improves the natural and cultural assets of the destination, the resident population quality of life, satisfies the tourists market, achieves a return on tourist operators, and achieves equity in the distribution of costs and benefits of tourism between current and future generations.

Considering the above approaches to sustainable tourism, it is noticeable that governance is the key element for implementing sustainable tourism [62]. Major changes in the governance of a place started at the beginning of globalisation and in many countries, especially after the transition from centralised to democratic countries, when marketing tools started to be introduced by self-government units to promote regions and towns as tourist attractions [63]. Place branding is implemented today as a governance strategy of local government units for creating better environmental, social, and economic conditions [41]. As stated in the literature, the Destination Marketing Organisations (DMO) play a significant role in the sustainable management of tourism destinations [22]. Here, it should be stressed that there is a difference between place and destination branding. The first kind of branding targets all stakeholders while the second one targets tourists and residents [14].

Despite the significance of sustainability, both inside and outside of the tourism industry, tourism is less sustainable than ever [64]. Undoubtedly public and commercial interest in environmental issues and their implications did lead to an expansion in the scope of marketing to appropriate concerns over the sustainability of resources and consumption [65,66,67,68,69,70].

The need for a response to tourist demands and local community expectations is clearly significant for tourism as it faces increased challenges with respect to sustainability and its contribution to society and destination economies [71]. There are many indicators which may measure the sustainability of the destination [72]. Examples include [73]:

- -

- resource use

- -

- waste pollution

- -

- local production

- -

- access to basic human needs

- -

- access to facilities

- -

- freedom from violence and oppression

- -

- access to the decision-making process

- -

- diversity of natural and cultural life.

Generally, there are three main dimensions of sustainability: environmental, economic and sociocultural [74,75]. However, there are many indicators that reveal the degree of sustainable tourism [76]. Taking into account the recommendations of sustainable development indicated by the United Nations [77], four main dimensions of sustainability should be indicated: economic, environmental, cultural, and locality (the sociocultural dimension has been divided into two: cultural and locality).

For the purposes of the research, the authors followed the sustainable tourism issues created by Tanguay et al. [76] who also pointed out the indicators suitable to each of the issues. The issues were divided into four categories and to each of them the visual symbols were examined in destinations’ logos.

3. Materials and Methods

An image, which could be photography, pictures, or graphics, is a part of contemporary social life. Therefore, contemporary social sciences increasingly study images to examine them as evidence of social illusions or hope [78]. This means that brands, including destination brands, are part of the cultural landscape, and the above-mentioned definitions of destination brand indicate that an important component of the brand is its visual identity [79].

The authors were aware of the imperfect option to make a shift from the case studies analysis to quantitative research. Therefore, all Polish town and county’s logos that were used in the public space at the time of scrutiny, have been reviewed. It turned out that of the 380 Polish towns and counties, 183 of them used signatures in marketing practice. All were analysed through the use of the content analysis research method.

Content analysis is a valid research method in place branding [80,81]. Govers, Go, and Kumar suggest that in destination research “The 3-Gap Destination Image Formation Model” is applicable. As they suggest, there is a strategic gap between the projected tourism destination image and the perceived tourism experience. However, to investigate and assess such a gap, one needs to analyse the situation from both sides, i.e., supply and demand [82]. In the presented research the authors examine the tourist destination promoters.

In the case of the graphic symbol analysis practiced in promotion, the research process consists of four stages [83] (pp. 56–66):

- finding images—destination logos were found on official webpages, social media, and in other promotional authorised publications;

- formulating categories for coding—coding means attaching a set of descriptive labels (or categories) to the images [83] (p.58);

- coding the images—applying distinguished categories to destination logos;

- analysing the results—formulating conclusions and discussion of the questions.

Visual content analysis is associated with many theoretical and practical complications, especially with reliability, replicability, accuracy and methods of sample selection for research. Referring to these issues, the authors followed the process of reliability assessment prepared by Neuendorf [84]: development of the coding scheme, practice coding, pilot reliability (it was done during previous researches of the authors), actual coding data and testing a sub-sample of units. The issue of repeatability and accuracy is related to the selection of the sample, which is why the authors decided to work with the full population of poviats and cities with poviat status in Poland. Such research may be repeated; the only difficulty may be changes of an administrative nature (e.g., establishment or liquidation of a poviat as an administration unit). The authors tried to accurately describe the research procedure, creating categories for coding and the coding process. It seems that the descriptions and examples contained in the article allow for the reconstruction of the research. The authors are aware of the limitations of the used research method, because it is not appropriate for research focused on the reception process [69]. However, as shown by other studies, the actions undertaken by authorities in charge of tourism have a fundamental impact on the creation of the identity and image of the destination brand [85].

4. Results

Taking into account the characteristics of sustainable tourism, the following symbols have been considered for analysis: graphical (logo), verbal (slogan), or a unification of both logo and slogan called a ‘slogo’ [86].

In the first stage—finding images—the authors decided to analyse the signatures of Polish towns and counties. That is why all such units were scrutinized: 66 towns and 314 counties (The administrative division of Poland is three-tier and includes: 16 voivodships (regions), 380 poviats (including 314 country [rural] poviats and 66 city-poviats) and 2477 communes). Searching on the internet, looking for documents, doing interviews with officials, and travelling across Poland, 190 signatures were collected (see Table 1). All of them were examined to verify the symbols communicating the destination as a place of sustainable development. Using a qualitative thematic coding methodology, a categorical framework for studying logos classification was created.

Table 1.

Number of local government units (LGU) analysed.

Coding is the stage in the examination process that moves from the collected data to abstract categories [87]. In the process of qualitative research, codes emerge directly from the research [87] (p. 95). In the presented study, key words were developed on the basis of the literature on sustainable tourism [49,88,89,90], but graphics intended to be visual symbols of these concepts emerged during the coding process as an outcome of this process. The strategy of the coding process involved image-by-image coding. For example, the image of flying birds was a symbol of nature in a destination. Then the collected codes were ordered according to previously worked out coding categories to present the data in the form of statistics.

Categories which represented sustainability of the tourist destination chosen to code the logo’s content were as follows:

- Economic sustainability:

- -

- local business

- -

- guidelines for training and certification

- -

- sustainable tourist behaviour promotion

- -

- products diversity

- -

- ethical marketing

- Ecologial sustainability:

- -

- ecological processes,

- -

- biological diversity

- -

- biological resources

- -

- symbols of nature

- Cultural sustainability:

- -

- cultural symbols

- -

- heritage

- -

- cultural diversity

- Local sustainability

- -

- local human capacity

- -

- local community symbols

- -

- indigenous people and traditional skills and jobs.

Since the year 2010, voivodship development strategies have perceived sustainability as the purpose of regional growth, but formerly the idea of environmental protection was developed in such strategies. That’s why, up to that year, the idea of sustainable tourism had not been implemented in any of the documents.

The process of coding, classifying and assigning to individual categories was carried out by the authors of the article in accordance with their knowledge, experience in logo researches, and defined codes.

A total of 352 items have been classified; their number is greater than the number of units, because some signatures, due to their complexity and multielement nature, were classified in several items (cf. e.g., Sulęcin County). The most common sustainability symbols come from the cultural sustainability category, symbols of ecological sustainability are the second category practiced in visual promotion, the third one is local sustainability, and economic sustainability visual signs are the least popular in such LGUs activities. As Table 2 shows, the most often are symbols of nature represented, followed closely by symbols of the past culture (heritage). The other signatures contain very diverse content. However, it should be emphasized that those related to local culture, local community, and local business are the most frequently used. What needs attention is a very poor representation of economic sustainability visual symbols. It seems that cities and counties do not communicate in their logos any signs connected with economic activities supporting sustainable development. Examples of signatures in categories of sustainability are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Categories symbolising sustainability in signatures of towns and counties.

Table 3.

Examples of signatures and their sustainably content.

In the case of a tourist offer addressed to customers from outside Poland, there is a difficulty with translation or foreign language versions of promotional slogans originally created in Polish (The authors would like to mention here that they conduct a research project on territorial branding in Poland and maintain regular contacts with LGU’s all over Poland what allows them to make such a general conclusion). Although Poland is a relatively large market for inbound tourism [92], in the case of marketing communication, the most common solution is a literal translation of the slogans from the native language into foreign one. There are translations that are linguistically questionable (for example “Chorzów—puts in motion”), but this does not affect the authors’ conclusions about the slogans. Untranslatable word games or puns are very rare, in such cases, promotional materials, descriptions, or additional explanations are used to explain the meaning of the slogans. Such an approach, i.e., a literal translation of a slogan in Polish into e.g., English, is justified by the following premises—tourist traffic in Poland is dominated by domestic tourists (80% of overnight stays), and foreign tourists’ expenses per capita are almost twice as high as Polish tourists [92].

The Table 4 contains information about the slogans of regional capitals in Poland. It comes from the official identification systems that the authors received from the relevant offices.

Table 4.

Slogans used by the capitals of Polish regions (voivodships).

5. Conclusions

Half of the surveyed local government units use visual signs, such as the logos in their promotional activities, and most of them communicate symbols representing the values of sustainable development. The quantitative analysis shows that local governments denotate mostly nature and cultural heritage in visual messages addressed to visitors and residents. Therefore, every fifth LGU recognizes nature as a symbol that denotes destination. Fewer destinations reveal their cultural past in visual signs, which means that the nature and traditional culture are expected to be recognised by the recipients of LGU visual messages. The local government units are also relatively attached to local values, which are presented in promotional signs. Especially important, disclosed by 10% of LGUs, is local human capacity.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The paper contributes to an understanding of logos functions in promoting sustainable tourism. LGUs, revealing the elements of sustainable development, consciously communicate features of a given destination associated with elements of sustainable development. They present themselves to the visitors as places friendly to sustainable development, caring for natural and historical heritage. However, it should be emphasised that ethical and economic categories, which are the principal features of sustainability, are marginally presented in the examined signatures.

When analysing the logo content of the Polish cities and counties, and considering a semiotic analysis, it should be emphasized that although nature and culture, which are important elements of sustainable development, are strongly represented, the connotation will be different. The iconic symbols of nature and traditional cultural objects, in the light of the contemporary expectations of the audience, would rather connote tradition, the past, and even conservatism.

Sustainable development, including sustainable tourism, is a symbol of the present, postmodernity, and in essence, is an idea directed towards the sustainable future. The Polish destinations’ signatures do not have such features. Therefore, the denotation is different from the connotation of these messages. The recipient receives the image of a traditional country that cares about nature and culture, but cannot identify the relationship between the Polish culture and nature with the economy, which, in accordance with the concept of sustainable development, should reveal symbols that allow us to think about a future reality similar to the current one. It is known from the researches that tourism has already shifted from traditional tourism to sustainable tourism and tourists might expect symbols clearly connected with economic and local sustainability, which in the examined signatures are poorly represented.

Indication, through consistent visual identification, of the sustainable type of a tourist offer has, from the point of view of DMO, at least two features:

- Such visual identification may build relationships with the local (host) community.

- It also may perform a sort of selective role in target markets.

From the communication point of view, the second feature is more important. The form of the offer itself automatically selects interested visitors for those looking for sustainable offers and not. The form of the message itself can tell who the desired customer is.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Research has shown that several sustainability indicators are significantly more numerous than others. They are symbols of nature (74), heritage of place (71), and local human capacity (41). It is commonly accepted that there are two primary goals in creating and managing a brand identity—description and distinction [93]. If so, many signs refer to the same symbols; distinguishing them can be difficult as they do not fulfill one of the basic marketing functions. Other studies, at least in the case of Poland, also indicate that the visual content is relatively poor and more or less literally represent things such as the sun, water, and greenery [94].

5.3. Discussion and Limitations

Although the authors made every effort to gather all signatures, the collected signature database is still incomplete. For example, there are logos that can be found on websites, but the lack of documentation makes it impossible to qualify (authors have found at least three such cases). The second reason why the database is incomplete is the variability of logos practiced in the management of cities and regions in Poland. Signatures are withdrawn, modified, or replaced by new ones, without official announcement. The image of the place presented by the signatures could change if you take into account the so-called investment signatures (e.g., logos created to encourage investors to invest in a particular place). However, this requires separate data collection methods as the sources are not widely available.

Another difficulty that limits the presented research is related to the relationship between the destination signature and the logo of the office (LGU administration of this destination) that holds the power in that destination. Moreover, there is also the difficulty of implementing visual identity for a particular destination. The process of development and implementation is very long, and the multitude of management procedures resulting from national law make it difficult. Multiple identification breaks down the uniformity of the brand, an issue noticed also by other researchers [51].

There is a question about the impact of logos and slogans on tourist’s perception. Do they influence tourists’ decisions, and if so—how effectively? Since the paper does not concern research on the reception of advertising messages, one can only indicate the direction of further research. Firstly, there are extensive analyses of territorial promotional slogans in Poland, which enable comparative research [95,96]. Secondly, practitioners emphasize the importance of the quality of slogans. Steve Cone, for example, emphasizes that official tourist slogans are “shallow and boring” [97]. Thirdly, this quality should be assessed not only in terms of logo content, but also the form, i.e., the impact on the reception of such elements as: shape, colour, fonts or unusual graphic solutions in the slogan (vide Szczecin “Floating garden”). As Gałkowski stresses [98] “The effectiveness of a slogan consists of a number of factors, also nonformal and nonintentional. The success of its use also depends on the cultural conditions”.

Therefore, the additional question arises of how to promote tourism when there is no uniformity in legal regulations and in governing the destination. For example, there are two types of communication: (1) formal—official communication practiced by a given LGU, which informs what activities in the field of sustainable development a town or region undertakes, and what the attitudes of the inhabitants toward sustainable tourism are, and (2) advertising communication that uses rhetorical artifices, which often allow for free interpretation of the message. This freedom in reading the content of the signatures as a visual identity is limited and even imposed by the verbal text—a slogan that specifies what the signature is about. As Eco wrote, there can be either concordance or incompatibility [50]. An image with a significant aesthetic function is accompanied by a slogan with an emotive function, or an image with a metaphorical structure is accompanied by a slogan with a metonymic structure. There could be a very business-like logo, but the slogan contradicts its content, as an example.

The results reported here add to the existing literature in the field data which show how signatures may promote a particular idea, in this case sustainable tourism. However, the results show that what is communicated in the signature content may have a completely different meaning for the recipient of the message. Natural, historical or cultural symbols do not imply that a destination is oriented towards sustainable tourism. According to the semiotics, the denotation of a sign may connote the opposite meaning. The fact that nature is promoted in the logo does not mean that it is properly protected in the promoted territory. Showing cultural goods in the visual promotion of the destination does not mean that they are valuable in the life of the local community.

5.4. Future Research

Further research should concern the recipient’s perspective. Knowing the content of signatures covering sustainable symbols does not mean that this content is perceived by recipients. The researches presented so far [3,99,100] mainly focused on case studies, including in the case of Poland.

Understanding tourists’ perception as to whether a particular destination supports sustainability is critical, especially today, during the COVID-19 pandemic [101]. However, such an issue is the subject of comprehensive research focused on the audience.

An important research direction may be the analysis of the inhabitants’ identification with the values of sustainable development. It can be assumed that the stronger the identification with these values, the stronger the acceptance of the visual expression of the specificity of a place as attractive due to these values.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D. and A.A.-M.; methodology, A.A.-M.; validation, J.M. and G.P.; formal analysis, J.M. and P.D; resources, P.D.; data curation, P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.M.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, G.P.; project administration, G.P.; funding acquisition, A.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pauwels, L. Urban Communication Research|Visually Researching and Communicating the City: A Systematic Assessment of Methods and Resources. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels, L. Conceptualising the ‘Visual Essay’ as a Way of Generating and Imparting Sociological Insight: Issues, Formats and Realisations. Sociol. Res. Online 2012, 17, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, P.M.; Palmer, C.; Lester, J.-A.M. (Eds.) Tourism and Visual Culture, 1st ed.; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84593-609-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C. Destination branding: Opportunities and new challenges. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganoni, M. City Branding and New Media: Linguistic Perspectives, Discursive Strategies and Multimodality; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-137-38795-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dunleavy, D. Visual Semiotics Theory: Introduction to the Science of Signs. In Handbook of Visual Communication. Theory, Methods, and Media; Josephson, S., Kelly, J.D., Smith, K., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B. Theoretical activity in sustainable tourism research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 54, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A. Designing Brand Identity: An Essential Guide for the Whole Branding Team, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-118-98082-8. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, M. Deconstructing Logo Design: 300+ International Logos Analysed and Explained by Matthew Healey; Rotovision: Brighton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, P.W.; Cote, J.A. Guidelines for Selecting or Modifying Logos. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Lans, R.; Cote, J.A.; Cole, C.A.; Leong, S.M.; Smidts, A.; Henderson, P.W.; Bluemelhuber, C.; Bottomley, P.A.; Doyle, J.R.; Fedorikhin, A.; et al. Cross-National Logo Evaluation Analysis: An Individual-Level Approach. Mark. Sci. 2009, 28, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walas, B. Znaczenie Logo Miast w Rozpoznawalności Miejsca Docelowego. Studia Oeconomica Posnaniensia 2014, 2, 264. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Yu, F.; Ding, X. Circular-Looking Makes Green-Buying: How Brand Logo Shapes Influence Green Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E.; Petersen, S. Branding the destination versus the place: The effects of brand complexity and identification for residents and visitors. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus-Matuszyńska, A.; Dzik, P. Tożsamość Wizualna Polskich Województw, Miast i Powiatów. Identyfikacja, Prezentacja, Znaczenie; Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek: Torun, Poland, 2017; ISBN 978-83-8019-602-5. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, K.A. Community Engagement: Exploring a Relational Approach to Consultation and Collaborative Practice in Australia. J. Promot. Manag. 2010, 16, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Page, S.J. Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkadi, E. City Branding: Proposal of an Observation and Analysis Grid. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 121–128. ISBN 978-3-030-36125-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, E.C. Humanistic Inquiry in Marketing Research: Philosophy, Method, and Criteria. J. Mark. Res. 1986, 23, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, A. Rationality and recognition. In Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences: A Pluralist Perspective; Della Porta, D., Keating, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 162–174. ISBN 978-0-521-88322-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S. Destination Marketing: An Integrated Marketing Communication Approach; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7506-8649-5. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper, N. The framework of tourism: Towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.M. Destination Management and Destination Marketing: The Platform for Excellence in Tourism Destinations. Tour. Rev. 2013, 28, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Pride, R. (Eds.) Destination Branding: Creating the Unique Destination Proposition; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-7506-5969-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kasapi, I.; Cela, A. Destination Branding: A Review of the City Branding Literature. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankinson, G. The management of destination brands: Five guiding principles based on recent developments in corporate branding theory. J. Brand Manag. 2007, 14, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Tourism destination branding complexity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A. Meeting the destination branding challenge. In Destination Branding: Creating the Unique Destination Proposition; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; pp. 59–78. ISBN 978-0-7506-5969-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.A. Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.-N. The New Strategic Brand Management: Advanced Insights and Strategic Thinking; Kogan Page: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7494-6515-5. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, M.S. Strategic branding of destinations: A framework. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florek, M. Podstawy Marketingu Terytorialnego; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2013; ISBN 978-83-7417-727-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nandan, S. An exploration of the brand identity–brand image linkage: A communications perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2005, 12, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecnik Ruzzier, M. Country brand and identity issues: Slovenia. In Destination Brands; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-136-34663-7. [Google Scholar]

- Çınar, K. Customer Based Brand Equity Models in Hotel Industry: A Literature Review. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 281–288. ISBN 978-3-030-36125-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zavattaro, S. Place Branding through Phases of the Image: Balancing Image and Substance. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-137-39443-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier, M.; Villeneuve, J.-P. Marketing Management and Communications in the Public Sector; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-136-50459-4. [Google Scholar]

- Percy, L. Strategic Integrated Marketing Communication: Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7506-7980-0. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, M. Branding as an Essential Element of the of Destination Management Process Using the Example of Selected States. Manag. Sci. Nauk. Zarządzaniu 2018, 23, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryluk, H.; Glińska, E.; Barkun, Y. Benefits and barriers to cooperation in the process of building a place’s brand: Perspective of tourist region stakeholders in Poland. Oeconomia Copernic. 2020, 11, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, C.; Levy, S.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination Branding: Insights and Practices from Destination Management Organizations. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, A.; Mottironi, C.; Corigliano, M.A. Tourist destination brand equity and internal stakeholders: An Empirical Research. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus-Matuszyńska, A.; Dzik, P. Measurement of Local Government Unit Marketing Orientation. Studia Ekon. 2017, 336, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Konecnik Ruzzier, M.; Petek, N. Country Brand I Feel Slovenia:First Response from Locals. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2012, 25, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, S. Reading Tourism Texts: A Multimodal Analysis; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-84541-428-3. [Google Scholar]

- Barisic, P.; Blazevic, Z. Visual Identity Components of Tourist Destination. World Acad. Sci. Eng. Technol. Int. J. Soc. Behav. Educ. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladou, S.; Kavaratzis, M.; Rigopoulou, I.; Salonika, E. The role of brand elements in destination branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.M. The semiotic paradigm: Implications for tourism research. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, U. La Struttura Assente: La Ricerca Semiotica e il Metodo Strutturale; Casa Editrice Valentino Bompiani & C.: Milano, Italy, 2016. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Beyrow, M.; Vogt, C. Städte und Ihre Zeichen: Identität, Strategie, Logo; Avedition: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3-89986-202-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Turystyka i Polityka Turystyczna a Rozwój: Między Starym a Nowym Paradygmatem; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.F. Sustainable tourism destinations: The importance of cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2001, 9, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.Q.T.; Young, T.; Johnson, P.; Wearing, S. Conceptualising networks in sustainable tourism development. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and Sustainable Development: Exploring the Theoretical Divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Higham, J.; Lane, B.; Miller, G. Twenty-five years of sustainable tourism and the Journal of Sustainable Tourism: Looking back and moving forward. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M. Mobilities and sustainable tourism: Path-creating or path-dependent relationships? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, T.; Bricker, K. Sustainable Tourism Development: The Long Road from Theory to Practice. Int. J. Econ. Dev. 2001, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E.; Price, G.G. Chapter 9—Tourism and sustainable development. In Global Tourism (Third Edition); Theobald, W.F., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 167–193. ISBN 978-0-7506-7789-9. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (Ed.) UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2002 Edition; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2002; ISBN 978-92-844-0687-6. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, B. Chapter 15. Destination Australia: A Reseach Agenda for 2002 and Beyond; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2003; pp. 341–357. ISBN 978-1-873150-49-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical research on the governance of tourism and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Meyer, D. Power and tourism policy relations in transition. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. A typology of governance and its implications for tourism policy analysis. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green Marketing; Pitman: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-7121-0843-0. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington, W.; Florian, P. Environmental Marketing: Positive Strategies for Reaching the Green Consumer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-07-011599-6. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam, Y.K.; Apeldoorn, P.A.C. Sustainable Marketing. J. Macromarketing 1996, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A. Marketing and the Natural Environment: What Role for Morality? J. Macromarketing 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P. The Sustainability of “Sustainable Consumption. ” J. Macromarketing 2002, 22, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. Toward the Institutionalization of Macromarketing: Sustainable Enterprise, Sustainable Marketing, Sustainable Development, and the Sustainable Society. J. Macromarketing 2012, 32, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. Tourism and Social Marketing; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-415-57665-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-415-41403-6. [Google Scholar]

- Conaghan, D.; Hanrahan, J.; McLoughlin, E. The Sustainable Management of a Tourism Destination in Ireland: A Focus on County Clare. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 3, 62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, N.; Laing, J.H. Backpacker tourism: Sustainable and purposeful? Investigating the overlap between backpacker tourism and volunteer tourism motivations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, B.; Alvarez, M.D. Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective of Sustainability in Cultural Tourist Destinations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay, G.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.-C. Sustainable Tourism Indicators: Selection Criteria for Policy Implementation and Scientific Recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenda 21 for the Travel & Tourism Industry. 1997. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284403714 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Magala, S. Antropologia wizualna. In Badania Jakościowe. Podejścia i Teorie; Jemielniak, D., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, J.; Salzer-Morling, M.S. Introduction: The Cultural Codes of Branding. In Brand Culture; Schroeder, J., Salzer-Morling, M.S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-0-203-00244-5. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Go, F. Place Branding: Glocal, Virtual and Physical Identities, Constructed, Imagined and Experienced; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-230-23073-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, A.R. Urban design and the entrepreneurial city: Place branding theory and methods. In Advertising and Branding: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 204–227. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R.; Go, F.M.; Kumar, K. Promoting Tourism Destination Image. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4739-6791-5. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K.A. Reliability for Content Analysis. In Media Messages and Public Health: A Decisions Approach to Content Analysis; Jordan, A., Kunkel, D., Manganello, J., Fishbein, M., Eds.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-203-88734-9. [Google Scholar]

- Dymond, S.J. Indicators of Sustainable Tourism in New Zealand: A Local Government Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 1997, 5, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, M. Slogany w Reklamie i Polityce; Trio: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; ISBN 978-83-88542-35-0. [Google Scholar]

- Glinka, B.; Hensel, P. Teoria ugruntowana. In Badania Jakościowe. PODEJŚCIA i Teorie; Jemielniak, D., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiee, S.; Rajabzadeh Ghatari, A.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Jahanyan, S. Developing a model for sustainable smart tourism destinations: A systematic review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Will sustainable tourism research be sustainable in the future? An opinion piece. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northcote, J.; Macbeth, J. Conceptualizing Yield: Sustainable Tourism Management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowska, A.; MIsiak, M. Paneuropa, Kometa, Hel: Szkice z Historii Projektowania Liter w Polsce; Karakter: Kraków, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Czernicki, Ł.; Kukołowicz, P. Maciej Miniszewski. In Branża Turystycznaw Polsce. Obraz Sprzed Pandemii; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mollerup, P. Marks of Excellence: The Development and Taxonomy of Trademarks Revised and Expanded Edition, 2nd ed.; Phaidon Press: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-7148-6474-7. [Google Scholar]

- Adamus-Matuszyńska, A.; Dzik, P. Logo w Komunikacji Marketingowej Samorządu Terytorialnego. Mark. Rynek 2017, 10, 26–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jędrzejczak, B. Słownik Sloganów Reklamujących Polskie Marki Terytorialne; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego: Gdańsk, Poland, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jędrzejczak, B. Językowe Środki Perswazji w Sloganach Reklamujących Polskie Marki Terytorialne Na Przykładzie Haseł Promujących Polskę, Województwa i Miasta Wojewódzkie; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego: Gdańsk, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cone, S. Superslogany. Słowa, Które Zdobywają Klientów i Zwolenników, a Nawet Zmieniają Bieg Historii; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gałkowski, A. Hasła Reklamowe Miast Polskich w Kontekście Urbonomicznym. Rozprawy Komisji Językowej ŁTN 2014, 67–79. Available online: http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-3082afe9-1b8c-4b32-9bd8-bda19da835fa (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Van, H.T.; Huu, A.T.; Ushakov, D. Destination Branding as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Development (The Case of Bangkok, Thailand). Adv. Sci. Lett. 2018, 24, 6339–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Florek, M.; Insch, A.; Gnoth, J. City Council websites as a means of place brand identity communication. Place Brand. 2006, 2, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Santos, L.; Cardoso, L.; Araújo-Vila, N.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A. Sustainability Perceptions in Tourism and Hospitality: A Mixed-Method Bibliometric Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).