1. Introduction

Industrialization of Europe contributed to the formation of generations. Such inventions as the steam engine, electricity, and medical progress have shaped the world to its present state, which we know today. Nevertheless, the rather rapid and intensive economic and industrial growth as well as the exploitation of natural resources contributed to changes in many areas and infrastructure, turning them into degraded, desolate land, impacting the natural environment significantly. The landscapes of natural regions had been completely changed, and the remains of the industrial period became a difficult problem to solve.

Owing to the development of industrial tourism, and above all, sustainable tourism, post-industrial facilities get new life [

1]. The idea of sustainable development replaces the emphasis on finding a perfect solution with the use of tangible and intangible values, which is important from the perspective of social life and would be lost if no activities have been undertaken [

2]. Therefore, the process of changing post-industrial buildings into tourist facilities, including tourist trails, is related to the design of sustainable development models as well as business models [

3].

An increased interest in industrial tourism has been noticed in the past decade. This trend is seen both in Europe and Poland. Industrial tourism becomes one of the best forms of promoting the tourist and cultural potential of a specific region, area, or city [

4].

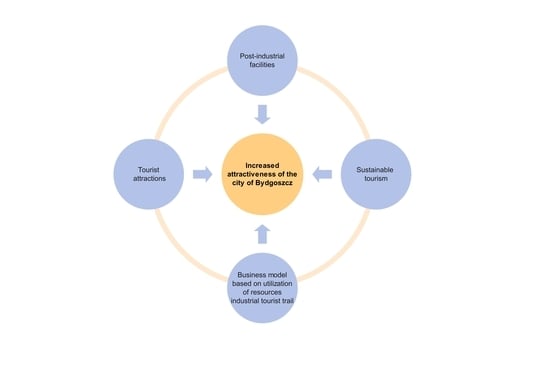

The purpose of this article is to determine the development of post-industrial facilities based on the TeH2O Industrial Themed Trail in Bydgoszcz serving as an example of industrial tourism and its impact on city attractiveness. It additionally indicates a business model that is based on resource utilization, in the form of industrial tourist trail landmarks.

In order to achieve these goals, it was necessary to conduct an analysis of the state of knowledge, the technology and the terminology related to development of post-industrial facilities, as to explain the role they play in contemporary tourism and discuss the topic of business models. The most important issue was to conduct a survey among the Bydgoszcz residents and visitors, in order to determine the impact that the development of post-industrial buildings has on the city’s attractiveness.

Development of post-industrial facilities for the purposes of industrial tourism becomes increasingly popular. Such activity allows for the protection of historic landmarks, equipping them with new roles, providing creative impact on the life of local residents, and facilitating development of new business models. All the advantages arising from heritage site revitalization contribute to the increasing number of industrial tourism advocates. Through their educational, historical, and creative character these sites become increasingly attractive to present-day tourists. One additional advantage of developed post-industrial facilities is the fact that they promote the locations, in which they are featured. In this way, they make the current industrial cities more interesting [

5]. A similar process can be seen in Bydgoszcz, where owing to the presence of the TeH

2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail, the city’s tourist attractiveness has considerably increased. The trail mentioned attracts a growing number of tourists from outside the city, who are interested in industrial tourism. Developed post-industrial facilities also provide important information about the region which they represent, raising interest among their visitors.

The trail’s full name is the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail. For the purpose of this article, the authors will also use other names in reference to the trail: TeH2O Trail, TeH2O Industrial Thematic Trail in Bydgoszcz, TeH2O Thematic Trail, TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail.

The TeH

2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz encompasses the following city heritage sites: The Exploseum, the Granaries on the Brda River, the Mill Island, the Bydgoszcz Canal, the Museum of Soap and the Dirt History, Water Tower, the Museum of Photography, the Bydgoszcz Beer Brewery, the “Pod Łabędziem” Pharmacy, the Water Supply Pump Hall, the Bookbinding Workshop, the Former municipal gas works, Woodworking Factory, the “Lemara” Barge, the Museum of the Bydgoszcz Canal [

6].

The TeH2O thematic trail was established as a result of the SHIFT-X project co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund and joined by the city of Bydgoszcz. The Bydgoszcz City Hall is thus the originator and the founder of the TeH2O Trail. Since 2016, the trail has been administered by the Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum, with only one person employed at the Department of Education and Promotion as the route coordinator.

The person responsible for the operation of the trail on behalf of the Leon Wyczółkowski District Museum is the Coordinator of the TeH

2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz. The coordinator’s main tasks include, inter alia, the following [

7]:

Representation of the entities operating as part of the trial in contacts with third parties;

Promotion and provision of information about the trail offer on behalf of all partners, development and implementation of promotional activities;

Implementation of all activities within the trial structure, i.e., communication between entities, development of a permanent offer as well as the issues related to customer service and tourism-related infrastructure, etc.

One important element of the trail’s functioning entails its support for the Bydgoszcz City Hall, which makes annual budget decisions and can issue recommendations for the Leon Wyczółkowski Distric Muesum regarding the functioning of the TeH2O Trail. The functioning of the trail is also assisted by the Bydgoszcz Information Center and the Kujawsko-Pomorska Organizacja Turystyczna (a tourist organization). The results of the survey conducted enrich the literature on sustainable industrial tourism and on development of post-industrial facilities in the context of creating business models. In addition, they serve as a recommendation for conduction of further quantitative research in this field. They provide good practice knowledge for the development of new tourist products—tourist trails based on post-industrial facilities, serving as a foundation for a business model.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Utilization of Post-Industrial Facilities and Industrial Tourism

Technological progress has significant impact on the way some things, goods, and articles of everyday use are made. Development of humanity, from the beginning of its existence, has influenced new discoveries and inventions. A huge part of it was so significant, that it resulted in the changes in the structure and organization of industry. These sites and—first of all—the post-industrial facilities in our surroundings have been identified for a relatively short time. They primarily pertain to city centers, which in the past two centuries had served as industrial centers. Nowadays they serve as relics of the industrial period, unique reminders, and historical witnesses of the bygone era [

8].

These areas or facilities, which ceased to operate as production plants or do not fulfill their other auxiliary functions associated with production, along with the areas of unfinished industrial projects, are called post-industrial areas or brownfield lands [

9]. Many post-industrial objects result from industrial revolutions, but they are also related to political system changes, business bankruptcies, as well as development of technology and science [

10,

11].

Depending on the time of development of post-industrial areas, these locations, both in Poland and Europe, had certain common features. During the 1930s, post-industrial facilities were located in city centers or on their outskirts, but also in close proximity to rivers. In the following decades (i.e., the 1960s and 1970s), along with the technological progress, post-industrial facilities were situated in the vicinity of railroads or thoroughfares [

12].

Both in Poland and Europe construction of many post-industrial facilities was determined by such factors as reduced coal mining and implementation of environmentally friendly solutions. It led to the restructuring of industry, which was losing its status. These activities resulted in profitability declines or even business closures experienced by many enterprises [

10,

13].

Many countries faced the problem of post-industrial facilities, not being sure how to treat them—as a burden, which should be discarded as soon as possible or as something useful, bringing benefits in the future. Many post-industrial facilities completely disappeared, or their purpose was suddenly changed. Frequently, due to hasty decisions, it had negative impact, causing irreversible long-term changes [

14,

15].

Tourism plays an increasingly important role in the economy, social activity, and the culture. According to the report published by the World Travel & Tourism Council, the tourism industry generates 10.3% of the global GDP, which translates to 8.9 billion American dollars [

16].

One of the reasons for post-industrial area utilization in tourism has contributed to the development of industrial tourism. It targets traveling, in which destination is determined by the cultural value of specific sites. This type of tourism encompasses not only heritage sites, but also contemporary landmarks. Revitalized post-industrial facilities blend in perfectly with the latest trends of today’s travelers who visit and search for new cultural experiences. Constant growth and promotion of industrial tourism is one of the priorities in the Polish tourism economy; it results from the fact that post-industrial facilities can play an important role in tourism as revitalized objects. Attention should primarily be paid to the way these facilities are developed in terms of attractiveness, education, and entertainment. Such activities allow the degraded, abandoned areas to breathe a new life into towns and regions, thus contributing to the development of society and improvement of culture. It has a positive impact on the locations and the level of their residents’ satisfaction. These activities are part of sustainable development and have positive impact on the creation of new business models on the part of the organizations operating in the tourism industry [

11,

17,

18,

19,

20].

2.2. The Process of Post-Industrial Facility Restructuring in the Light of the Law

The problem of post-industrial facility and area development can be recognized as a common issue. Such areas and objects can frequently be distinguished by the attractive location and infrastructure, preserved at varying levels. Studies and analyses have led to the development of practical tools, which are focused on post-industrial area restructuring. These tools include proper organizational structures, legal regulations, procedures, and model projects [

14,

21,

22].

The solutions implemented proved to be necessary for ensuring reasonable, compliant with the principle of sustainable development, implementation of the activities carried out in these areas, which places emphasis—first of all—on natural protection and fulfilment of the present generations’ aspirations, keeping in mind the future generations, through efficient utilization of natural resources, e.g., energy savings and reduction of environmental pollution [

23,

24].

Under the Polish law, the first document regulating the issues related to brownfield land is the government program for post-industrial areas, passed by the Council of Ministers on 27 April 2004. The program mainly aimed to determine the conditions and mechanisms used for the development of post-industrial areas, maintaining the principles of sustainable development [

25,

26].

The act on revitalization (Journal of Laws 2015, art. 1777), which was passed on 9 October 2015 is the first Polish regulation focused on this issue. Brownfield land and post-industrial facilities were incorporated into revitalization areas. It results from the fact that development thereof will contribute to the prevention of negative social phenomena. Economic phenomena include the fact that local business is in bad shape and the quality of environment poses serious threats to people [

27].

Analyzing the legal acts that are currently in force in Poland, it can be concluded that revitalization activity in post-industrial areas requires specific conditions. One of the most important conditions entails assurance that a post-industrial area, as a result of restructuring, solves the social problems mentioned in art. 9 sec. 1 items 1–4 of the act on revitalization [

27].

2.3. Utilization of Business Models

Business models have been known in foreign and Polish literature on the subject for more than several decades [

28,

29]. The significance of business models in contemporary business can be characterized by the clear difference existing between management practitioners and theoreticians [

30].

In Polish literature, different definitions of business model can be found [

31]. T. Falencikowski characterizes business model as a “relatively isolated, compound conceptual object, describing the running of business through articulation of the logic of creating values for customer and interception of part of this value for an enterprise” [

32]. P. Timmers, on the other hand, defines business model as product, service, and information flow architecture, including a description of the various business actors; and a description of the sources of revenues [

33]. D. Teece claims that business model is a tool used to design a mechanism for creation, delivery, and value capturing for customer purposes [

34].

One of the main tasks of business models entails description of business, explaining how a given company works and the ways to develop competitive advantage on the market [

35]. It additionally describes the relations between the organization’s components leading to the creation and capture of its value [

36]. Business models are flexible and have to be adjusted to the changes that take place in markets, the innovations, and the legal frameworks. Business model is regarded as a way of building business and adding value for its customers [

37].

Business models are complex—they consist of many models, which incorporate a range of activities in an organization, starting from the organization as a whole, and ending with models of individual business units, products, or processes [

38,

39,

40].

It should be noted that in the source literature, business models for regional products consist of entry and exit conditions, quality standards, and mechanisms for control and improvement. They additionally should clearly identify the social, image-related and financial benefits, specifying their financing [

41].

Currently, one of the most serious threats resulting from tourism is the burdens caused by overtourism. Creation of business models, which combine sustainable development and value for businesses is therefore important [

42]. Such business models can constitute a significant source of competitive advantage, generating many economic benefits [

36]. Nowadays, owing to their affordability and versatility, business models are used in an increasingly higher number of industries, i.e., in industrial, food, tourist, energy, and other enterprises [

43].

Development of new business models in tourism allows for the generation and maximization of profits [

44]. One reason for this is the development of information technology, which owing to its mobility can transform the tourism market not only in Poland, but also globally. Moreover, the information technology progress has contributed to increased competitiveness of the companies operating on the tourist market [

45].

Companies operating in the tourism industry, wanting to create a business model, should keep in mind that it is supposed to reflect the mechanisms of the activities that contribute to the achievement of their targets [

46]. One important aspect is the ability to modify business models. Frequently, this ability is perceived as a precondition for dealing with changes that can result from the surrounding as a consequence of an economic decline or due to the permanent transitions of the market in terms of supply and demand [

47].

2.4. Industrial Tourist Trail as a Model of Sustainable Tourism

Utilization of post-industrial facilities is part of sustainable tourism. According to the European Commission, sustainable tourism is tourism that is economically and socially profitable, not affecting the environment and the local culture [

48]. The concept of sustainable tourism was developed along with the implementation of sustainable development [

49,

50]. During the conference dedicated to sustainable tourism in 1995, the Charter for Suitable Tourism was adopted, which was accepted by the biggest international organizations, such as the World Tourism Organization, the United Nations Environment Program, UNECSO, and the European Commission [

51].

Sustainable tourism became part of the New Urban Agenda as one of the sectors that can have significant impact on the development of urban economy and the creation of new, high quality jobs. The significant growth of industrial tourism can be associated with various activities that not only are focused on tourist traffic stimulation, but above all have a positive impact on the economy, the life of the local people, helping avoid the negative effects of overtourism in urban space, paving the path toward sustainable development of tourist initiatives, which is beneficial for both the tourists and the residents [

52]. Creation of themed tourist trails incorporating post-industrial facilities, is therefore a positive undertaking, from the perspective of sustainable tourism and economy.

The idea of themed trails emerged from the dynamic development of industrial tourism, which utilizes brownfield land and post-industrial facilities [

53]. One of the biggest themed trails operating across Europe is the European Route of Industrial Heritage (ERIH). In Poland, there are ten trails of this type, which are part of the European Route of Industrial Heritage [

54,

55].

It should be noted that the ERIH does not encompass all the trails. We should therefore pay special attention to the trails that are not part of this European giant with regard to the post-industrial facility aspect, the cultural trails in Poland can be divided into two types. The first type comprises trails with post-industrial facilities featuring several industrial heritage landmarks. Another type consists of industrial trails dedicated fully to industrial heritage. Currently, in Poland, there are about 600 cultural trails, 7% of which are industrial trails [

56]. The TeH

2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz belongs in this group of trials.

The intertwining of history, industry, and environmental protection gave rise to the development of a regional business model. The TeH

2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz combines public buildings with private property. A business partnership exists between the tourist route facilities and the numerous facilities within the infrastructure surrounding the route. This, among others, promotes the trial and results in the improvement of the functioning of the local economy. The trail is multi-productive, which means that tourists can use many products or services. Such a combination improves the local economy and promotes the trail. Existence of business partnership fosters the competitive advantage of the tourist region and facilitates the development of enterprises that are able to cooperate within such a network. Owing to the development of the business model, the effectiveness of advertisement and promotion cost minimization, in relation to the trail objects and locations, has improved. Access to information on the building of a position in the market improved, along with the ability to make decisions faster. Development of a business model that brings together post-industrial facilities enabled funding from the previously mentioned international SHIFT-X project co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund. A network of entrepreneurs emerges around the trail. The building of a business model facilitated acquisition of new knowledge-sharing skills pertaining to the ability of finding best solutions in case of problems. The business model also increased the innovation capacity of the trail participants. As a result, it is possible to create innovative industrial heritage products. The products associated with the business model developed include, among others: organization and coordination of tourist services (sightseeing, organization of tours), the monitoring of the route and facility markings, promotion of the trail and its facilities, updating and distribution of information about the trail, distribution of various materials about the trail, initiation and coordination of thematic products for tourists, sale of own services, etc. The TeH

2O thematic trail addresses its offer both to the inhabitants of Bydgoszcz and the tourists, the passers-by who decided to visit the city. The customers who have decided to take advantage of the thematic trail offer can, first of all, learn about the people and the events in the industrial heyday of Bydgoszcz. The visitors can additionally take advantage of the following: a single entry ticket to many facilities, a system of discounts (e.g., for workshops) for the recipients visiting more than one facility, discounts on the services provided by the facilities/entities in the vicinity of the trail, co-creation of offers for business (company meetings, integration events, etc.,). TeH

2O thematic trail intends to acquire new partners in the coming years (new facilities on the route, new facilities/accompanying entities), but above all, to acquire new key foreign partners for the development. Development of an offer for new groups of recipients (foreign tourists) is one of the key elements of a long-term strategy. The development strategy additionally includes continuous emergence of new products offered as part of the trail [

7,

43,

57,

58]. It is worth adding, that some regions were not very popular among tourists, but their inclusion in the trail has become one of the main development factors for those locations.

3. Materials and Methods

The study used both secondary and primary data sources. The first part of the research entailed a survey carried out via free online questionnaire tools. The target survey group involved two sets of respondents—the residents of the city of Bydgoszcz and the tourists visiting Bydgoszcz.

The subject scope of the study encompassed Bydgoszcz as a tourist destination, in particular the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail. The time frame was 2015–2019. The study of primary sources was carried out in 2019.

The questionnaire was made available on social media—i.e., Facebook, associating the biggest group of Bydgoszcz residents, as well as on theme groups addressing tourism and sightseeing. The Facebook groups—My (Our) Bydgoszcz, Bydgoszcz Fordon, Bydgoszczanie, Bydgoszczanki, Tourism, Must-See Historic Sites, and various groups associated with specific neighborhoods of the city.

The study entailed a non-random sample selection, i.e., the purposeful selection method was used. The research was divided into two parts. The first part involved a survey carried out among the residents of Bydgoszcz, whereas the second part involved a survey carried out among the tourists visiting Bydgoszcz. The survey time range was set at one month. After the data collection stage was completed, the authors acknowledged the number of the survey questionnaires received as appropriate for the first part of the analysis and enabling verification of the research assumptions. During the data reduction stage, none of the questionnaires received was rejected. Total of 212 people took part in the first part of the study. In the second part of the study, the population was 208 persons. The total number of the respondents was thus estimated at 420 persons.

Table 1 shows the structure of the research sample.

The questionnaire consisted of 16 questions. Ultimately, the questionnaire included an imprint with questions about gender, age, education, and employment status. In the category of closed questions, the authors offered multiple selections of answers and a frequency scale of certain phenomena. The questionnaire concerned the assessment of the city’s tourist attractiveness and industrial tourism, taking into consideration the assessment of a number of aspects related to the examined TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz.

Analysis of the questionnaire results was preceded by a description of Bydgoszcz tourism.

Figure 1 presents the statistical indexes of the tourist traffic in Bydgoszcz. The information on to the number of tourists visiting Bydgoszcz was published by the Bydgoszcz Information Center [

20,

59,

60,

61,

62]. The number of tourists in Bydgoszcz over the past five years was increasing systematically. Such factors as improvement of the hotel service quality as well as the increased number of beds and tourist facilities have most likely contributed to the growing number of tourists. Additionally, in the period described, new flights were added to the schedule of the Bydgoszcz Airport, thus affecting the increased number of the tourists coming from abroad.

The survey participants represented various employment groups and different levels of education.

Table 2 shows the sample structure in employment distribution. Among the respondents from Bydgoszcz, the biggest group comprised white-collar (office) workers, whereas the unemployed constituted the smallest group.

The most diverse group of the surveyed consisted of the tourists visiting Bydgoszcz. The biggest groups included students, white-collar workers, and blue-collar (manual) workers. Just like in the case of residents, the unemployed constituted the smallest group. The survey result comparison is presented in

Table 2.

The greatest share of the surveyed, in age distribution, i.e., both the residents of Bydgoszcz and the visitors, was the group of people aged 21 to 30. The results are shown in

Table 3. Because of the educational nature of post-industrial tourism, the authors considered the large share of this group purposeful and appropriate for the assessment of the phenomenon under examination.

The next stage of the study entailed an in-depth interview with the Coordinator of the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz. Because of spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the interview was carried out remotely. At the request of the Coordinator of the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail, all questions were sent by e-mail. The authors of the study also used secondary sources, most important of which was the report on the tourist traffic in Bydgoszcz in 2015–2019, prepared by Leszek Woźniak and the Bydgoszcz Information Center and made available by the City of Bydgoszcz—Bydgoszcz Information Center.

4. Empirical Study Results

The non-resident (visitor) respondents were asked if they have visited the city or plan to do so in the coming year. Based on the study, it has been found that 177 survey participants (85%) had visited the city of Bydgoszcz. Whereas 93 survey participants (4.7%) intended to do so, and 75 (36.1%) did not express their opinion on this matter.

Additionally, they were asked about the purpose of their trips to Bydgoszcz.

Figure 2 presents their answers.

The respondents from the city of Bydgoszcz stated that the city is touristically attractive. Such an opinion was expressed by 97 respondents (45.8%). The visiting respondents shared a similar opinion. This opinion was expressed by 81 respondents (38.9%).

Table 4 presents the detailed results of the Bydgoszcz tourist attractiveness assessment expressed by the respondents.

During the research, the respondents were asked about the knowledge of the TeH2O industrial trial. Out of the city of Bydgoszcz inhabitants, as many as 60.4%, i.e., 128 respondents, stated that they have heard about this route, while 34.9%, i.e., 71 respondents, were not familiar with what the trial analyzed was, and 4.7%, i.e., 10 respondents, were unable to indicate any answer. The results were similar in the case of the question addressing the fact of visiting an industrial trial object. These results are as follows: 60.4%, i.e., 128 resident respondents had visited a trail facility, 23.1%, i.e., 49 respondents, had not, while 16.5%, i.e., 35 respondents, were unable to indicate whether they had visited any of the facilities of the industrial trial.

The visiting (non-resident) respondents’ answers to same question were as follows: 72.6% have never heard about the TeH2O Industrial Trail, 16.8% are familiar with it, and 10.6% did not provide any answer. The visitors’ answers to the question regarding visiting any of the sites on the Industrial Trail can be summarized as follows: 54.8% have not visited any of the sites, 13.9% visited one of the sites, and as much as 31.3% were not able to state if they have visited any of the sites.

The surveyed were asked to provide their opinion on the share of the TeH

2O Industrial Trail in the assessment of the city’s attractiveness. The answers provided ranged from 1 to 6, where 1 indicated the smallest share and 6 the greatest.

Table 5 presents the assessment results for both groups of the respondents.

The respondents were then asked about their assessment of industrial tourism. They were to mark their opinion of industrial tourism on a 5-point scale, where 1 meant completely unattractive, and 5 very attractive. The full range of the answers provided is shown in

Table 6.

The figure below (

Figure 3) shows assessment of the development of post-industrial facilities on the TeH

2O Trail.

The questions contained in the in-depth interview addressed assessment of the city’s attractiveness, its industrial tourism and the share of the Water, Industry and Craft Trail in this scope. Other issues that were discussed included the establishment of the TeH2O Trail as well as the source of and the purpose behind this undertaking. Information on the attendance, the marketing strategies and the economy was included as well.

In the coordinator’s opinion, based on the survey answers obtained, the city’s attractiveness has significantly increased when it began to be associated with the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail. The residents’ awareness of the industrial value of Bydgoszcz was very important as well. Development of post-industrial facilities for tourist purposes has breathed new life into those sites, allowing the history of these sites to be presented, thus reaching a wide group of its offer recipients. The Coordinator of the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail stated that industrial tourism is a perfect answer to the tourists’ ever increasing demand for new experiences. It mainly results from the fact that such tourism combines the function of sightseeing with the knowledge of the world, the familiarization with technology and production processes, as well as the history of these sites, facilities, and societies. Some of the reasons that led to the establishment of the Trail include the need for protection and promotion of the industrial heritage of Bydgoszcz, the strive for increased awareness among the residents and the administrators of post-industrial facilities. The Coordinator of the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail also stated that the idea of the TeH2O Trail is based on the assumption that technology does not exist without the man. The Coordinator mentioned that annually the Trail reports about 100–150,000 entries, with a steady growth in the trend. She also emphasized the difficulty in the estimation of the number of the people who are aware of the Trial’s existence and choose recreation on the Młyńska Island or the Bydgoszcz Canal. The city’s residents account for a significant share among the Trail visitors.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The article presents an example of restructured areas and facilities affected by past industrial activity. The laws and regulations in force allow restructuring of post-industrial facilities for tourism-related purposes. It should be mentioned, however, that every post-industrial area exhibits different features, which result from many variables, e.g., the type of the industrial activity conducted in the past, its location, the society’s needs, the degradation level of the facility, and/or the area and the surrounding environment, the administrative authority’s prospects, as well as the feasibility of investment plans.

The authors described the laws and regulations pertaining to the changes indicated as well as examples of development, in relation to the facilities and areas that meet specific social problems. The current state of this issue in Poland has been presented as well. Other key topics include description of post-industrial area utilization for tourism purposes and the role of industrial tourist trails as an example of business model.

The study and the literature analysis allowed the research objective to be achieved. Development of post-industrial facilities for tourist purposes is an attractive form of tourism, which results from the information obtained via numerous references, statistics, and the research addressing topic. More than 60% of the respondents residing in Bydgoszcz have visited the post-industrial facilities located on the TeH2O Trail. Their assessment of the attractiveness this type of tourism offers, 43% of the surveyed selected answers 4/5, and 36% of the respondents selected answer 5, where on the 5-point scale, 1 meant completely unattractive, and 5 very attractive. The non-resident respondents have also visited the TeH2O Industrial Trail sites, but only at a 13.9% rate.

The method of post-industrial object development on the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz has been assessed as well. Also in this case vast majority’s opinion was positive. The respondents assessed that it is an example of a very interesting post-industrial area utilization; this opinion was expressed by 26% of the resident respondents and 50.6% of the non-resident (visiting) respondents. Moreover, 41% of the respondents from Bydgoszcz answered that the Trial embodies an interesting form of post-industrial facility development. Conversely, 25.6% of the non-resident respondents recognize that the Trial constitutes a perfect combination of technology, history, and spatial development. The development of industrial tourism had also a positive impact on the improvement of the environment. Thematic routes are a perfect example of how post-industrial facilities can be used in a sustainable way, which fits with the canons of sustainable tourism.

The authors of the article did not find results similar to the research conducted. The authors searched such databases as: Google Scholar, BazEkon, Scopus, etc. No similar publications addressing to the research field that would allow comparison of the results with the hypothesis and objectives set at the beginning of the study have been found. The lack of similar studies may result from the fact that industrial tourism, and in particular tourist routes, have only gained popularity in the recent years. It is therefore necessary to indicate the need for research in this area.

The research conducted in 2018 by Zawadka et al. [

63] on the popularity of the tourist routes located in the rural areas of the Podlasie and Masovian voivodeships shows familiarity and the popularity of this type of tourist routes is low. The most famous trail is the Chopin Trail (Chopin’s Mazovia). The authors indicate that, on average, over half of the respondents were not aware of the existence of the routes analyzed. These routes are known to the persons residing in the vicinity of those objects. The lack of familiarity with the routes analyzed may result from poorly implemented promotional activities that were aimed at popularization of such tourist attractions.

A research conducted by Krzysztof Widawski et al. [

55] on the tourist attractiveness of the objects making up the Land Flowing with Milk and Honey trail indicates that only one of the 22 sites analyzed is of low attractiveness.

Nevertheless, the research carried out by the above-mentioned authors does not specify how the thematic routes examined affect the attractiveness of the places in which they are located. It is therefore important to take the problem identified in the research into account.

Based on the research carried out and the authors’ observations, several conclusions can be drawn:

Development of post-industrial facilities for the purpose of industrial tourism has become an increasingly popular solution, aimed at attracting a growing number of recipients. The research allowed a conclusion that development of post-industrial facilities significantly improves city attractiveness, thus contributing to the promotional activities of these cities and regions. As such, the cities that had once been known for their industry, later degraded and forgotten, now can rebuild their identity and show their history.

The TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz has had considerable impact on the increase of the city’s attractiveness. The Trail has become a tourist destination for both the residents of the city of Bydgoszcz and the visitors. Owing to the inflow of tourists in the past years, the TeH2O Trail can be popularized both domestically as well as in Europe.

The TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz offers great potential for the region, which when properly utilized can bring measurable benefits. Among the benefits arising from the TeH2O Trail there are economic advantages, including the profits generated by specific landmarks located on the Trail as well as the general hospitality of the services situated in the proximity of the Trail, i.e., hotels, restaurants, souvenir shops, etc., prevail. It should be noted that industrial tourist trails improve the competitive position of any region. They also strengthen the social, economic, cultural, and spatial ties within their area.

This significant increase in the popularity of industrial tourism in Poland requires proper adjustment of the industrial heritage and the sightseeing packages are presented. It is important that such offers are addressed to individual tourists, groups of tourists, and tour operators. It is also necessary to develop a clear, easily available landmark information system that would provide details on the sites to be visited and the themed trails operating in Poland. Moreover, such landmarks should be better promoted in mass media. This problem can thus be solved by the development of a business model that would entail utilization of resources, i.e., the components comprising a themed trail, via an online service, which would serve as a tool allowing the tourists to create their own itinerary, adjusted to their needs and providing many other functionalities.

According to the studies conducted by the authors, the TeH2O Industrial Trail is better known among the residents of the city of Bydgoszcz than the visitors (non-residents). This may result from the fact that the Trail is insufficiently advertised outside Bydgoszcz. It also should be mentioned that many people visiting sites of the TeH2O Industrial Trail were not aware that specific landmarks are part of this Trail.

The city of Bydgoszcz is a place where industrial history plays a very important role. Many post-industrial buildings can be found there which set the city’s rhythm. This is one of the reasons why the authors of the article engaged in the topic of business models preserving the historical value of the city. The design of such models, which are based on post-industrial facility development, is a perfect example of activities that are aimed at monument protection and simultaneous creation of business ties between the trail participants.

The authors of this article are aware that the study does not provide representative results and the data received cannot be generalized onto the entire population. Nevertheless, the results of this study can serve as a foundation for in-depth research in this field.

It thus rightly concluded that development of post-industrial facilities for tourism purposes, by establishment of a themed tourist route, such as the TeH2O Water, Industry and Craft Trail in Bydgoszcz for instance, is a just, needed, and attractive solution. Utilization of post-industrial facilities generates measurable benefits, not only in economic or social, but also in ecological terms.