How Can Companies Decrease Salesperson Turnover Intention? The Corporate Social Responsibility Intervention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Development

2.1. Salespeople’s CSR Perception and Perceived Corporate Reputation

2.2. Salespeople’s CSR Perception and Organizational Pride

2.3. Perceived Reputation and Organizational Pride

2.4. Organizational Pride and Salesperson Turnover Intention

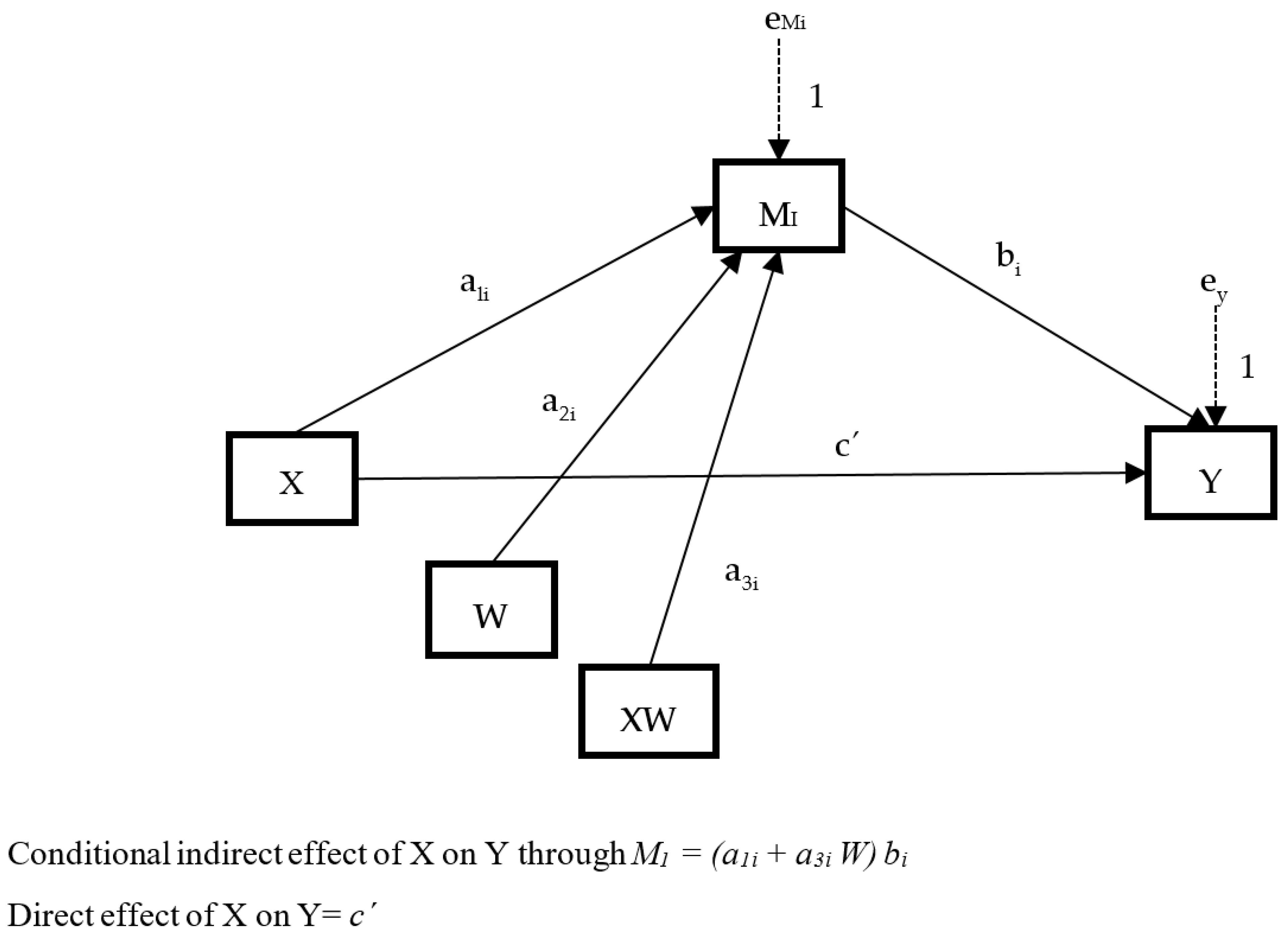

2.5. Turnover Intention: Mediation Hypotheses

2.6. Interpersonal Justice: Moderation Hypothesis

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection Procedure and Sources

3.2. Measures

3.3. Measurement Model (Scale Validity and Reliability)

3.4. Common Method Variance Bias and Multicollinearity

4. Results

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Aguinis, H. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization. APA Handbooks in Psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.-P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How Do Employees Perceive Corporate Responsibility? Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Corporate Stakeholder Responsibility Scale. J. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Qadeer, F.; Shahzadi, G.; Jia, F. Getting paid to be good: How and when employees respond to corporate social responsibility? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Chen, L.-F. Boosting employee retention through CSR: A configurational analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Qun, W.; Abdullah, M.; Alvi, A. Employees’ Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Employee Outcomes: Mediating Role of Organizational Justice for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gond, J.-P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Farooq, O.; Cheffi, W. How Do Employees Respond to the CSR Initiatives of their Organizations: Empirical Evidence from Developing Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bourdeau, B.; Graf, R.; Turcotte, M.-F. Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility as Perceived By Salespeople On Their Ethical Behaviour, Attitudes And Their Turnover Intentions. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2013, 11, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Theotokis, A.; Panagopoulos, N.G. Sales force reactions to corporate social responsibility: Attributions, outcomes, and the mediating role of organizational trust. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1207–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Yam, K.C.; Aguinis, H. Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2019, 72, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunder, S.; Kumar, V.; Goreczny, A.; Maurer, T. Why Do Salespeople Quit? An Empirical Examination of Own and Peer Effects on Salesperson Turnover Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, I.D.; Brashear Alejandro, T.; Foreman, J.; Chelariu, C.; Bergman, S. Social norms in the salesforce: Justice and relationalism. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F.; Mulki, J.P.; Solomon, P. The role of ethical climate on salesperson’s role stress, job attitudes, turnover intention, and job performance. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2006, 26, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, J.B.; Johnson, J.T. The Effects of Perceived Supervisor Support, Perceived Organizational Support, and Organizational Justice on Turnover among Salespeople. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2009, 29, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comaford, C. Salespeople Are Burning out Faster than Ever—Here’s Why. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinecomaford/2016/06/18/how-leaders-can-engage-retain-top-sales-talent/ (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Hansen, J.D.; Riggle, R.J. Ethical Salesperson Behavior in Sales Relationships. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2009, 29, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, O.C.; Johnston, M.W.; Marshall, G.W.; Ferrell, L. A New Direction for Sales Ethics Research: The Sales Ethics Subculture. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2019, 27, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.L.; Baxter, R.; Glynn, M.S. How salespeople facilitate buyers’ resource availability to enhance seller outcomes. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Priporas, C.-V. The effect of mobile retailing on consumers’ purchasing experiences: A dynamic perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.; Song, H.J.; Lee, C.-K. Effects of corporate social responsibility and internal marketing on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 55, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Moore, J.H.; Wang, Z. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Outcomes: A Moderated Mediation Model of Organizational Identification and Moral Identity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Newman, A.; Shao, R.; Cooke, F.L. Advances in Employee-Focused Micro-Level Research on Corporate Social Responsibility: Situating New Contributions within the Current State of the Literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sidhu, A.; Beacom, A.M.; Valente, T.W. Social Network Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Boles, J.S.; Dudley, G.W.; Onyemah, V.; Rouziès, D.; Weeks, W.A. Sales Force Turnover and Retention: A Research Agenda. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2012, 32, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R.M. Social Exchange Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Psychology: An Integrative Review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Gupta, A.; Chaker, N.N. The pull-to-stay effect: Influence of sales managers’ leadership worthiness on salesperson turnover intentions. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.; Sandvik, K.; Selnes, F. Direct and Indirect Effects of Commitment to a Service Employee on the Intention to Stay. J. Serv. Res. 2003, 5, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Smith, J.E.; Shalley, C.E. The Social Side of Creativity: A Static and Dynamic Social Network Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fombrun, C. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image; Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P. Reputation as an Intangible Asset: Reflections on Theory and Methods in Two Empirical Studies of Business School Reputations. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meca, E.; Palacio, C.J. Board composition and firm reputation: The role of business experts, support specialists and community influentials. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018, 21, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, J.; Pruyn, A.; de Jong, M.; Joustra, I. Multiple organizational identification levels and the impact of perceived external prestige and communication climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidts, A.; Pruyn, A.T.H.; Van Riel, C.B.M. The Impact of Employee Communication and Perceived External Prestige on Organizational Identification. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walsh, G.; Mitchell, V.-W.; Jackson, P.R.; Beatty, S.E. Examining the Antecedents and Consequences of Corporate Reputation: A Customer Perspective. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.B. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Hi, N.; Blumberg, I. The Link between (Not) Practicing CSR and Corporate Reputation: Psychological Foundations and Managerial Implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic Implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arikan, E.; Kantur, D.; Maden, C.; Telci, E.E. Investigating the mediating role of corporate reputation on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and multiple stakeholder outcomes. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. Emerging Insights into the Nature and Function of Pride. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 16, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Madey, S. Why Are Job Seekers Attracted by Corporate Social Performance? Experimental and Field Tests of Three Signal-Based Mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellemers, N.; Kingma, L. Corporate social responsibility as a source of organizational morality, employee commitment and satisfaction. J. Organ. Moral Psychol. 2011, 1, 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck, K.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V. Consistency Matters! How and When Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Employees’ Organizational Identification? J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1141–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.R.; McIntosh, T.; Reid, S.W.; Buckley, M.R. Corporate implementation of socially controversial CSR initiatives: Implications for human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Yu, Y. The Influence of Perceived Corporate Sustainability Practices on Employees and Organizational Performance. Sustainability 2014, 6, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. Autonomous vs. comparative status: Must we be better than others to feel good about ourselves? Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2002, 89, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrend, T.S.; Baker, B.A.; Thompson, L.F. Effects of Pro-Environmental Recruiting Messages: The Role of Organizational Reputation. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghapanchi, A.H.; Aurum, A. Antecedents to IT personnel’s intentions to leave: A systematic literature review. J. Syst. Softw. 2011, 84, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Azami, A. An Analysis on the Relationship between Work Family Conflict and Turnover Intention: A Case Study in a Manufacturing Company in Malaysia. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, J.; Dukerich, J.; Harquail, C. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gouthier, M.H.J.; Rhein, M. Organizational pride and its positive effects on employee behavior. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker-Wright, J. Moral Status in Virtue Ethics. Philosophy 2007, 82, 449–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydyk, J. A Capability Approach to Justice as a Virtue. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 2012, 15, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.C. Justice as an Emotion Disposition. Emot. Rev. 2010, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.L.H.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colquitt, J.; Scott, B.; Rodell, J.; Long, D.; Zapata, C.; Conlon, D.; Wesson, M. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: A meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 199–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.J.; Mossholder, K.W.; Harris, S.G. Justice and job engagement: The role of senior management trust. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.E.; Pappas, J.M. The Role of Trust in Salesperson—Sales Manager Relationships. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2000, 20, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, J. The Impact of Justice Type on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Do Outcome Favorability and Leader Behavior Matter? Curr. Psychol. 2015, 34, 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Applicants’ and Employees’ Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility: The Moderating Effects of First-Party Justice Perceptions and Moral Identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, B.C.; Harold, C.M. Interpersonal Justice and Deviance. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, M.R.; Kudret, S. Multi-foci CSR perceptions, procedural justice and in-role employee performance: The mediating role of commitment and pride. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, S.H.; Moon, T.W.; Hur, W.M. Bridging Service Employees’ Perceptions of CSR and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Moderated Mediation Effects of Personal Traits. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Hur, W.; Kang, S. Employees’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility and Job Performance: A Sequential Mediation Model. Sustainability 2016, 8, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brislin, R.W. The wording and translation of research instruments. In Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research; Lonner, W.J., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1986; pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Mathieu, J.; Rapp, A. To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fournier, C.; Tanner, J.F.; Chonko, L.B.; Manolis, C. The Moderating Role of Ethical Climate on Salesperson Propensity to Leave. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2010, 30, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Sadd, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 1609182308. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, M.K.; Singhal, C.; Shang, G.; Ployhart, R.E. A critical evaluation of alternative methods and paradigms for conducting mediation analysis in operations management research. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.F. Moderation in Management Research: What, Why, When, and How. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, M. Equity, Equality, and Need: What Determines Which Value Will Be Used as the Basis of Distributive Justice? J. Soc. Issues 1975, 31, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Kulik, C.T. Third-party reactions to employee (MIS)treatment: A justice perspective. Res. Organ. Behav. 2004, 26, 183–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M. Employee Participation in CSR and Corporate Identity: Insights from a Disaster-Response Program in the Asia-Pacific. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2009, 12, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, I.; Seele, P. Theorizing stakeholders of sustainability in the digital age. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobko, P.; Stone-Romero, E.F. Meta-analysis may be another useful tool, but it is not a panacea. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Elsevier Science/JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 359–397. ISBN 0762303689. [Google Scholar]

- del Mar Alonso-Almeida, M.; Perramon, J.; Bagur, L. Women managers and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in Spain: Perceptions and drivers. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2015, 50, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Chica, O.; Tapia Frade, A.; De Diego Vallejo, R. Does a socially responsible prototypical leader exist in Spain? Cuad. Gest. 2019, 19, 53–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, C.; Fay, S.; Xiang, K. When do we need higher educated salespeople? The role of work experience. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSR | 5.38 | 0.97 | ||||||

| 2. Reputation | 5.67 | 1.05 | 0.59 ** | |||||

| 3. Pride | 5.85 | 1.18 | 0.53 ** | 0.63 ** | ||||

| 4. Justice | 6.33 | 0.79 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |||

| 5. Turnover | 2.36 | 1.65 | −0.21 ** | −0.26 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.05 | ||

| 6. Gender | 1.55 | 0.50 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.01 | −0.01 | |

| 7. Age | 41.13 | 8.74 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.21 ** |

| Consequences (Model 6) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (Reputation) | M2 (Pride) | Y (Turnover) | |||||||

| Antecedents | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p |

| Constant | 2.33 | 0.56 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 0.61 | 0.04 | 6.15 | 1.06 | <0.001 |

| CSR | 0.63 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.96 |

| Reputation | --- | --- | --- | 0.54 | 0.08 | <0.001 | −0.06 | 0.15 | 0.68 |

| Pride | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | −0.49 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Control Variables | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p |

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.74 | −0.13 | 0.14 | 0.35 | −0.18 | 0.24 | 0.46 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.32 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.59 |

| R-squared | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.15 | ||||||

| F | 30.37 | 30.37 | 5.77 | ||||||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Direct effect | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| CSR->Turnover | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.95 | −0.29 | 0.31 |

| Indirect effect | Effect | BootSE | p | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| CSR->Reputation->Turnover | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.61 | −0.15 | |

| CSR->Reputation->Pride->Turnover | −0.17 | 0.11 | −0.34 | −0.07 | |

| CSR->Pride->Turnover | −0.15 | 0.07 | −0.32 | −0.05 | |

| Total effect | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| CSR->Turnover | −0.35 | 0.13 | 0.01 | −0.60 | −0.10 |

| Consequences (Model 7) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 (Pride) | Y (Turnover) | |||||

| Antecedents | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p |

| Constant | 2.96 | 0.62 | <0.001 | 6.20 | 1.15 | <0.001 |

| CSR | 0.29 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.96 |

| Reputation | 0.51 | 0.08 | <0.001 | −0.06 | 0.15 | 0.68 |

| Pride | --- | --- | --- | −0.49 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Justice | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.33 | --- | --- | --- |

| CSR x interpersonal justice | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.02 | --- | --- | --- |

| Control variables | Coeff. | SE | p | Coeff. | SE | p |

| Gender | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.51 | −0.18 | 0.24 | 0.46 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.63 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.59 |

| R-squared | 0.68 | 0.38 | ||||

| F | 23.84 | 5.77 | ||||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Indirect Effect | Justice Values | Effect | Boot SE | LLCI * | ULCI ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR->Pride->Turnover | 5.25(Percentile10) | −0.25 | 0.10 | −0.50 | −0.09 |

| 6.00(Percentile 25) | −0.17 | 0.07 | −0.36 | −0.06 | |

| 6.50(Percentile 50) | −0.13 | 0.06 | −0.29 | −0.03 | |

| 7.00(Percentile 75) | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.24 | 0.02 | |

| 7.00(Percentile 90) | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.24 | 0.02 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castro-González, S.; Bande, B.; Vila-Vázquez, G. How Can Companies Decrease Salesperson Turnover Intention? The Corporate Social Responsibility Intervention. Sustainability 2021, 13, 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020750

Castro-González S, Bande B, Vila-Vázquez G. How Can Companies Decrease Salesperson Turnover Intention? The Corporate Social Responsibility Intervention. Sustainability. 2021; 13(2):750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020750

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastro-González, Sandra, Belén Bande, and Guadalupe Vila-Vázquez. 2021. "How Can Companies Decrease Salesperson Turnover Intention? The Corporate Social Responsibility Intervention" Sustainability 13, no. 2: 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020750