1. Introduction

Research on immigrant entrepreneurship has received special attention in the field of American immigration and ethnic studies since the 1970s [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Fong and Chan [

7] found that, at the beginning of the 20th century, most immigration studies focused on the social and community aspects of immigrant adaptation. Moving beyond early studies on the immigrant community, they reported that between 1990 and 2004, sociological immigration studies addressed an array of topics covering the various dimensions of immigrant integration [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. The economic dimension of immigrant adaptation addresses the attainments and advancement of immigrants [

11] and the economic performance of immigrants compared to that of the native-born population [

13]. There was also a surge in the study of immigrant entrepreneurship in terms of participation and operations [

14,

15,

16]. In a review of research on immigrant entrepreneurship in the United States, Morawska argued that immigrant entrepreneurial activities were interpreted first in terms of immigrants’ ethnicization, then assimilation, and, most recently, transnationalism [

4].

An ideal global city, New York represents a classic case for understanding the defining features of contemporary entrepreneurial activities [

17,

18,

19,

20]. As a gateway city, New York’s demographic and economic profile changed dramatically between 1970 and 1990 [

4]. Internationalization of New York’s economy and population, especially the inflows of new immigrants and their settlements, added to the increased vibrancy of the city’s traditionally cosmopolitan culture and economic life [

21,

22]. The demand for cultural goods and services also increased with the growth of immigrant populations, mainly from Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean [

4,

23,

24]. Studies of immigrant entrepreneurship in the USA tend to focus overwhelmingly on large, well-established and visible populations such as Chinese [

25,

26,

27], Dominican [

26,

28,

29,

30], and Jamaican entrepreneurs [

31,

32] in New York, Korean immigrant entrepreneurs in Los Angeles [

33] and Cuban immigrant entrepreneurs in Miami [

34,

35]. By contrast, the business activities of the less entrepreneurial immigrant groups were rarely investigated.

Among the new Asian immigrant communities, there are many whose entrepreneurial activity was hardly reported in the existing literature. The Bangladeshi community is a case in point. While recent and still relatively small, Bangladeshi migration to the United States grew and diversified in the last few decades. A vibrant Bangladeshi community is emerging in the USA, creating a sustained demand for various ethnic goods and services. The research on a new immigrant community, such as the Bangladeshi and their businesses, is expected to offer valuable insights into a new immigrant community and shed light on the ways in which immigrant businesses emerge within the contemporary immigrant population.

Thus, this study made two points: first, we are not adequately aware of new immigrant groups who have moved to the USA since the late 1980s, and second, although management literature on entrepreneurship emphasizes innovation in small businesses, ethnic business studies tend to overlook the importance of innovation, probably due to the marginality of most immigrant businesses. This study attempted to advance our understanding in both areas. Empirically, this study addressed the following questions. Who are these migrant entrepreneurs? Why do they seek to open businesses? How do they mobilize resources for business? What makes them entrepreneurs? Broadly, this study explains the shifts in individual immigrants’ trajectories from immigrants to immigrant entrepreneurs by examining group characteristics of Bangladeshi immigrants, the opportunity structure that New York offers them, and the innovations that migrant entrepreneurs introduce to their businesses to make them unique and rewarding. Empirically, this study examines the emergence of immigrant businesses among Bangladeshis in New York. As a gateway city, New York attracts a large number of new immigrants who eventually choose to settle in the city. There is a burgeoning Bangladeshi community in New York, giving us a sufficient reason to choose New York for fieldwork.

The following section presents theoretical issues related to the development of immigrant entrepreneurship, followed by research methods undertaken for this study, and patterns of Bangladeshi immigration to the USA. The group characteristics and the strategies for resource mobilization are presented in the next sections, followed by an examination of the nature of the businesses, and descriptions of the innovation strategies they employ. The final section concludes with key findings and direction for future research.

2. Immigrant Businesses and Entrepreneurship: The Theoretical Issues

There exists a considerable body of literature on various aspects of immigrant and ethnic businesses in North America and Europe [

5,

22,

36]. The existing literature has primarily discussed immigrant groups’ cultural values and orientations, resources, organizations, and motivation for immigration as important cultural factors and structural discrimination, disadvantages associated with immigrant status, and cheap ethnic labor as key structural factors in the development of immigrant entrepreneurship [

15,

37,

38,

39,

40]. To explain the development of immigrant businesses, a number of theoretical models were developed over time. For instance, the transplanted cultural thesis holds that immigrants carry certain traditional values of their home country, and their imported cultural properties facilitate their entry and success in entrepreneurial ventures in a host society [

41,

42,

43]. The class and ethnic resources model points to the class properties and ethnic resources that immigrant groups tend to possess, and their ability to mobilize such resources through economic insertion into the host country [

44]. The sojourner thesis which presumes that early Chinese immigrants in America were sojourners who intended to make and save money and then return to their home villages for a better life [

45]. This seems in many ways irrelevant in the present context. The blocked mobility thesis argues that immigrants face structural barriers in entering the labor market, forcing them to gravitate towards self-employment [

46,

47]. Building on the common observations that native-born Americans tend to have a lower self-employment rate than their foreign-born counterparts, Light and Bonacich advance the disadvantage theory to explain the disparity [

33]. It seems that the transplanted cultural thesis, the class and ethnic resources theory, the blocked mobility thesis, and the disadvantage theory continue to influence and shape immigrant businesses today in one way or another.

In addition to the cultural-structural dichotomy, there is another set of dichotomy, namely, the supply-side and demand-side of entrepreneurship in which the supply side refers to cultural properties and ethnic resources of immigrant groups and the demand-side points to the contextual forces of the host society in the development of the immigrant entrepreneurship [

48]. A common criticism of cultural or supply-side analysis is its inadequate appreciation of the economic and institutional environment in which immigrant entrepreneurs function. Criticisms of structural or demand analysis include its inadequate emphasis on cultural properties and ethnic resources [

49].

On the conceptual theoretical level, the debate takes the familiar form of arguing which has priority of influence: culture, structure, or a fusion of the two. Waldinger and his associates argued in favor of an approach that considered immigrant groups’ social and cultural features, as well as the contextual or external forces, and suggested the integrative approach to immigrant entrepreneurship [

50]. Broadly, Waldinger et al. [

49] introduced the opportunity structure and the group characteristic as an integrative approach and elaborated various components that constitute market conditions and access to ownership, on the one hand, and immigrants’ predisposing factors and resource mobilization on the other [

49,

51,

52]. The argument was that the opportunity structure, or the demand for immigrant goods and services, and the group characteristics, or the supply of skills and resources of immigrants, offer a fertile ground for immigrant entrepreneurship to flourish.

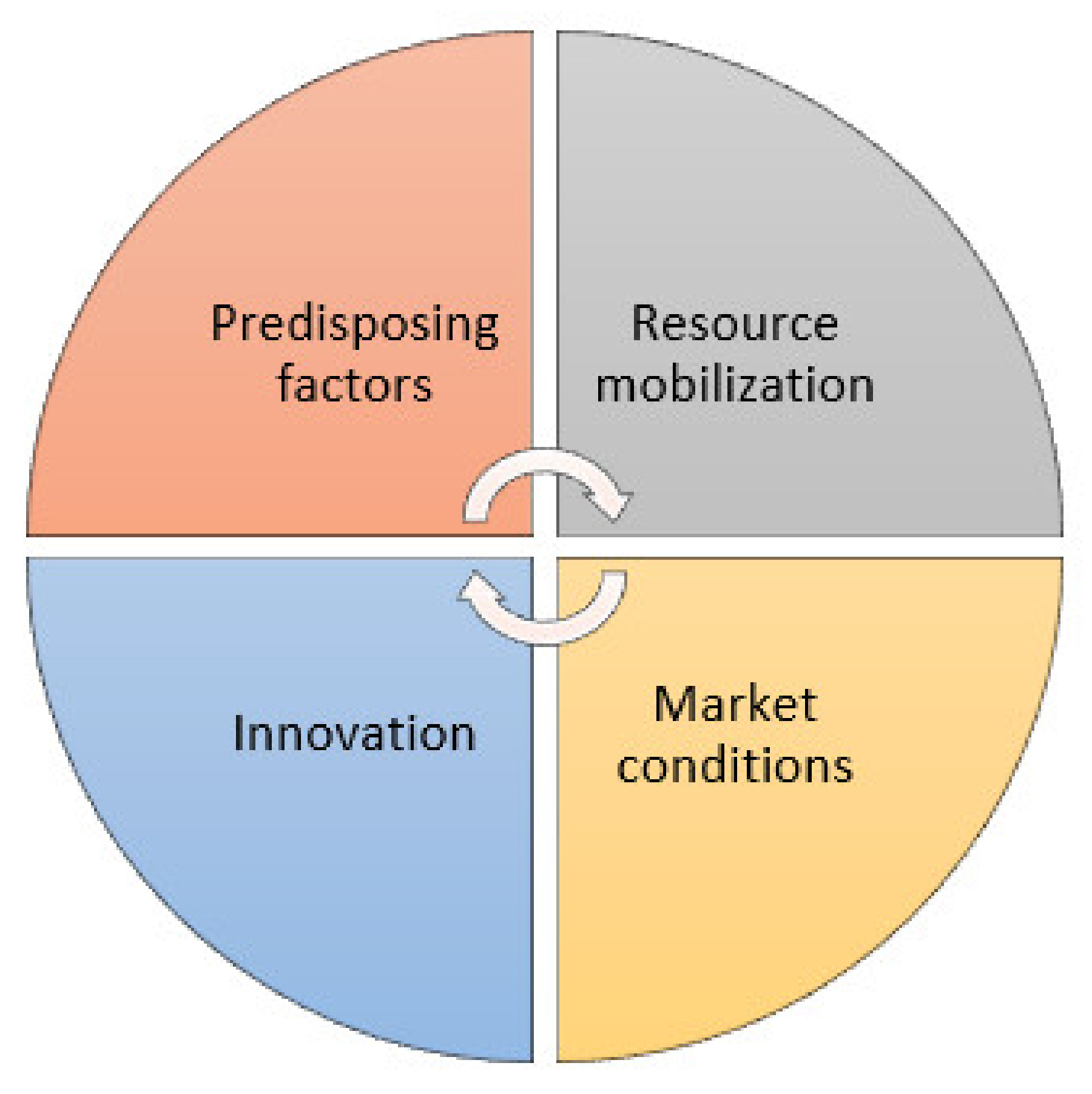

Immigrant entrepreneurs tend to apply innovative strategies to participate in both the ethnic and non-ethnic market and, thus, penetrate new, rewarding markets. This research builds on predisposing factors, resource mobilization, and market conditions elaborated by Waldinger et al. [

53] in ethnic entrepreneurship literature [

49] and innovation explained by Engelen in immigrant businesses.

Figure 1 shows that predisposing factors, resource mobilization, market conditions, and innovation interact in the emergence of new immigrant businesses. Despite their marginal character, as this study shows, many small immigrant entrepreneurs have thrived owing to the ingenuity of individual immigrants and their motivation to innovate for wider market. Evidently, the ingenuity of individual entrepreneurs comes to play a role in the development of immigrant entrepreneurship. In particular, Schumpeter’s notions of entrepreneurship, combination, and innovation were important for this research (p. 74, [

54]). Schumpeter used the concept of combination to define entrepreneurship and suggested that entrepreneurship consists of making new combinations. A new combination, in Schumpeterian word an “innovation”, was considered a novel way of merging already existing “resources”, “materials” or “means of production” (pp. 192–193, [

55]).

Schumpeter mentioned the five types of innovation, such as the introduction of a new good and a new method of production, identification of a new raw material and a new market, and finally a new organization of an industry [

54]. Pursuing any one or all of the five types of innovation may be described as innovative strategies. In the Schumpeterian sense, the essence of entrepreneurship lies in using existing resources in a new way to accomplish new goals [

54]. According to Engelen [

56], innovation refers to an attempt to make one’s business as dissimilar as possible from competitors. The literature on immigrant businesses often disregards the use of innovative practices in immigrants’ micro-enterprises [

1]. This tendency to undermine the importance of innovation is probably attributable to the marginal character of most immigrant enterprises [

56]. This paper builds on Engelen’s work, especially his “breaking out” strategies [

56]. A break-out strategy broadly alludes to the endeavor of immigrant businesses to move out of the immigrant market niches and exploit the wider market [

57]. Break-out strategy was a topic of much interest in research on the development of immigrant enterprises in recent years [

58,

59,

60]. This research examined the breaking out process by highlighting Bangladeshi immigrants’ innovations in product, process, marketing, sales and distribution, and integration and cooperation.

3. Data Sources and Methods

The concepts of “immigrant entrepreneurship” and “ethnic entrepreneurship” are interchangeably used in this paper. By immigrants, we mean those people who moved to the USA for permanent settlement. In line with Dheer, we refer to immigrant entrepreneurship as a process whereby immigrants identify new economic opportunities in their host country and embark on new enterprises as a move to create and exploit opportunities [

2]. Bangladeshi immigrant entrepreneurs run various types of businesses to cater to the demands of co-ethnic clientele, and beyond, across the United States. We define micro-enterprises operationally as enterprises with few employees and relatively little start-up capital. Our study principally includes low-end, micro-enterprises with traditional ethnic orientation. Empirically, this study documents Bangladeshi small businesses in New York City. There are many Bangladeshi entrepreneurs who are involved in high-end market niches, serving exclusively non-ethnic clientele in the USA. However, we have not included such high-end enterprises in our study. We selected small businesses with ethnic orientation deliberately as this would allow us to show how these immigrant businesses are moving out to the wider market by employing various break-out strategies.

In total, 50 Bangladeshi immigrant entrepreneurs were purposively selected for interviews. These 50 entrepreneurs represented over 29 types of micro-enterprises. The rationale for choosing 29 types of micro-enterprises was to avoid repetition and over-representation of particular businesses in our sample. However, the list was not exhaustive; it excluded other types of businesses due to lack of accessibility, availability, and resource constraints. The surveyed businesses represent a wide spectrum of businesses that serve multi-ethnic and multiracial clienteles. We first conducted informal discussions with immigrants and immigrant entrepreneurs to gain insights into the development of immigrant businesses among community members. Later, we developed a questionnaire and conducted a pilot study with a number of immigrant entrepreneurs. A semi-structured interview schedule was developed and run to elicit information on demographic attributes, business type, mobilization of resources, legal constraints, and, finally, the innovative strategies employed to stay in and expand upon business. Information on respondents’ gender, family size, immigration status, years taken to start the present business, business partnership(s), number of full-time and part-time employees, children’s career plans, information on siblings and parents are presented in the relevant sections. The fieldwork for this study was conducted with Bangladeshi immigrants turned entrepreneurs located primarily in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Manhattan in New York City.

The interviews were supplemented by participant observation and discussions with Bangladeshi immigrants and other South Asian immigrants who were also part of the broader clientele for immigrant entrepreneurs. Such individual and group meetings also rendered much needed insights into the emergence of entrepreneurship among the Bangladeshi immigrants in New York City. In the interview process, we collected business cards, product promotional flyers, price lists, pictures of some important products, and other available documentation. Respondents were interviewed in their mother tongue, Bengali, for convenience. As the authors of this paper are native Bangladeshi, language and cultural skills and connections with Bangladeshi community members were added advantages to this research. During the fieldwork, some respondents were reluctant to be interviewed at first; however, we were eventually able to gain their trust through our social connections and successfully interview them.

4. The US Immigration Context: New Immigrants

White [

61] divided the history of U.S. immigration into five waves: wave I (1565–1802), wave II (1803–1868), wave III (1869–1917), wave IV (1918–1968), and wave V (1969–present). The first four waves principally involved migration to the United States from European nations. Between the 1880s and the early 1920s, over 23 million European immigrants arrived in the United States (p. 5, [

62]). The 1965 Amendments to the Immigration Act, popularly called the Hart-Celler Act, are often considered a decisive break in U.S. immigration policy landscape [

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]. The enactment of the Hart-Celler Act on July 1, 1968 changed the basis for entry to the U.S. in alignment with the following priorities: (a) promotion of family reunification, (b) filling of labor market vacancies, and (c) accommodation of refugees and asylum seekers [

61,

67]. This allowed a sustained, pronounced shift in the source countries and regions of immigrant inflows, with Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean emerging as the principal source regions over time [

68,

69].

The most significant of the other legislative changes that were made following the passage of the Hart-Celler Act were the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (i.e., the IRCA) and the Immigration Act of 1990. The IRCA provided amnesty for many undocumented immigrants. The Immigration Act of 1990 increased the annual number of arrivals to 700,000 and created a diversity visa program [

61]. White calculated the inflow of immigrants during the years 1968–2015 and reported that nearly 37 million immigrants arrived during this period (p. 83, [

61]). Unlike prior periods (the first four waves of immigration), only 11.9 percent of all immigrants arrived from Europe, whereas Latin America and the Caribbean accounted for 44.4 per cent in total. Interestingly, 31.2 percent of all arrivals originated from Asia between 1968–2015 (p. 82, [

61]).

In the social and political frontier of the United States, there was a remarkable shift in acceptance of new immigrants in the 20th century. Despite being a settler country, the U.S. did not allow ethnic and hyphenated identities in the early 20th century [

62]. To some in the early 20th century, hyphenated Americanism even “amounted to un-Americanism” (p. 9, [

70]). In the 1940s, the notion of “melting pot” found a place in the textbooks for the first time [

62]. A new notion of “beyond the melting pot” emerged as a revision to the American self-image by the early 1960s [

71]. By the end of 1960s, the phrase “nation of immigrants” became widely popular and, by the late 20th century, being a hyphenated American became commonly accepted [

72].

International migration was an important feature of the landscape of Bangladesh since its independence in 1971. Kibria [

73] identified two major streams of Bangladeshi migration overseas. The first migration stream involved labor migration from Bangladesh to primarily the Gulf States, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, Iraq, Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar. Since the 1980s, international labor migration from Bangladesh has expanded to new destinations like Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, and Brunei. The second stream of international migration from Bangladesh included the developed world, namely, to the United States as well as to European countries. Although the noticeable migration of Bangladeshis to the USA started in the 1980s, a handful of people from the present-day Bangladesh landed in the USA as early as the 1920s [

74,

75,

76]. They are considered the first wave of Bangladeshis and mainly worked as seafarers and jumped the ship in the port city of Detroit, Michigan in the 1920s and 1930s [

77].

From the 1990s onwards, Bangladeshis first started to immigrate to the U.S. in a considerable number and continued to do so under special visa programs such as the Opportunity Visa and the Diversity Visa.

Table 1 presents the growth of Bangladeshis obtaining lawful permanent residence in the United States between 1973 and 2018. As

Table 1 suggests, there was a sharp increase in the growth of Bangladeshis obtaining permanent residence from the 1990s onwards. Two changes in the USA immigration policy are often attributed to this sharp rise [

78]. The first was the legalization of previously undocumented immigrants through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), which legalized foreigners living in the country unlawfully since 1982. The second was the introduction of new visa programs, such as the Opportunity Visa and the Diversity Visa. These visa programs clearly influenced the development of the Bangladeshi community throughout the United States [

73,

77,

78,

79].

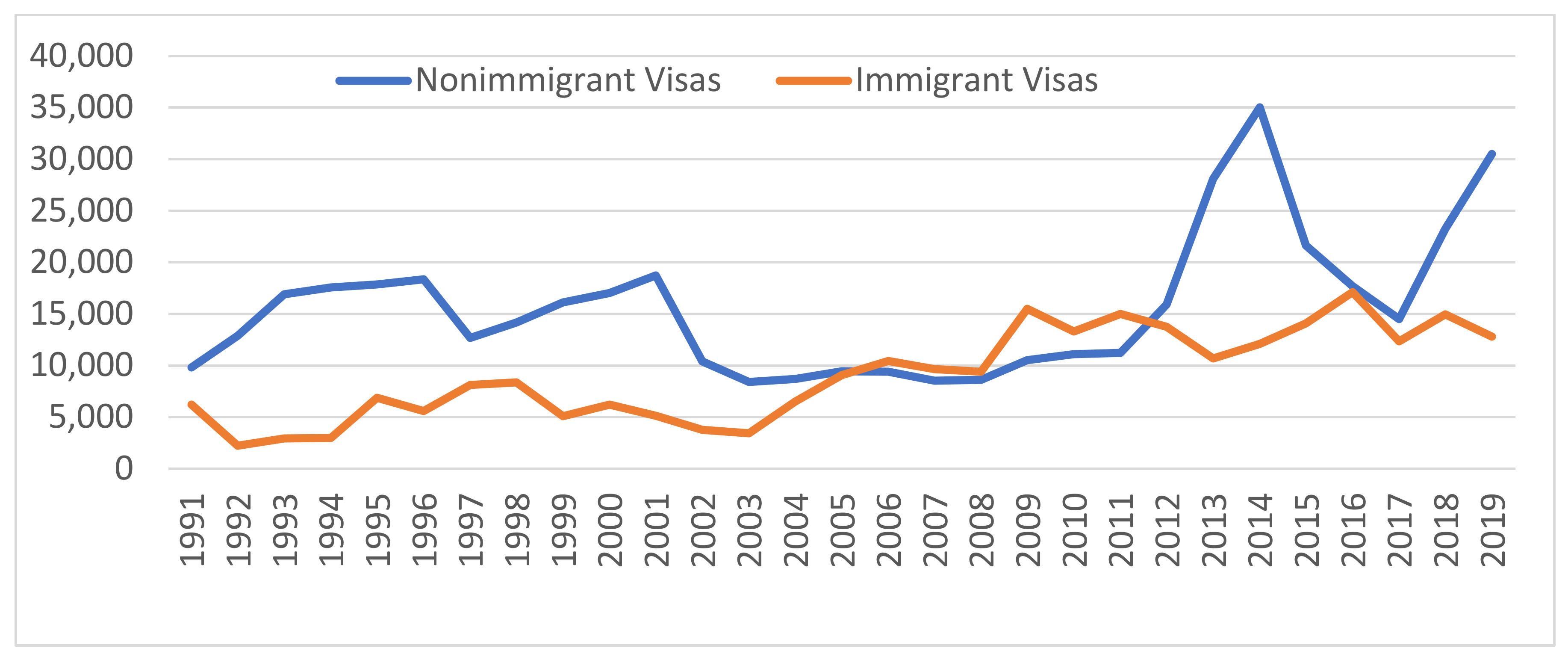

Figure 2 presents the number of immigrant and non-immigrant visas issued to Bangladeshis between 1991 and 2019. According to the estimates of the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs, 263,681 immigrant visas were issued to Bangladeshis between 1991 and 2019. There was a sharp drop the first few years after 9/11 and immediately after the beginning of the Trump administration. A large number of Bangladeshis were issued non-immigrant visas, totaling 455,215, between 1991 and 2019. The growth of non-immigrant visas was steady, except for a drop during the first few years after 9/11. Many of these non-immigrant visa holders stayed back in the USA with various regular and irregular immigration statuses. In total, nearly 719,000 immigrant and non-immigrant visas were issued to Bangladeshis to travel to the USA.

We found steady growth of the Bangladeshi permanent resident population in the USA (

Table 1). As

Table 1 suggests, around 312,877 Bangladeshis obtained permanent resident status from 1973 to 2018. The patterns of growth of permanent residents are interesting; in the years between 1973 and 1984, the annual growth rate of permanent residents was below 1000. In the years between 1985 and 1995, the annual growth rate increased from 1000 residents to over 6000 residents, with the exception of 10,676 residents in 1991. In the years between 1996 and 2004, the annual increase was roughly 8000 residents (

Table 1). There was a sustained increase of annual growth from nearly 11,000 in 2005 to 15,717 in 2018. It is important to note that this number excludes early immigrants and children of Bangladeshi-American citizens and residents. Considering the immigrant and non-immigrant visas and the growth of permanent residents, it is obvious that a vibrant Bangladeshi immigrant community is emerging in the US, creating demand for various ethnic goods and services across the country.

5. Predisposing Factors

Information on respondents was elicited to understand and identify some predisposing factors for starting businesses in the USA. All surveyed respondents were male, except two respondents who were female entrepreneurs involved in special types of enterprises, namely a tutoring center, dedicated to helping immigrant children cope with academic pressure, and a driving school. Of the 50 respondents, three quarters were aged above 40 years, 18 respondents were aged between 41 and 50 years, and 17 were aged above 50 years. The remaining four entrepreneurs were aged between 20 and 30 years, and 11 were aged between 31 and 40 years. This finding was not surprising; most of the entrepreneurs older than 30 first looked for fortune in different occupations and before finally starting their own businesses. The younger entrepreneurs made early moves to run businesses. Most of the respondents (47 respondents) were married with children, whereas two were unmarried living with their extended families at the time of the interviews, and one was a divorcee living with two children. The average family size of the respondents was 4.04 members.

All surveyed respondents had completed various levels of education in Bangladesh, except one who studied in the USA as an undergraduate. In terms of educational attainment, 13 respondents held postgraduate degrees or master’s degrees (16 years of schooling or more), 23 held bachelor’s degrees or BAs (14 years of schooling or more), 10 held a “higher secondary certificate” or HSC (12 years of schooling), and only four held a “secondary school certificate” (10 years of schooling or more). The educational attainment of the respondents was higher than that of Bangladeshi entrepreneurs in other countries, such as Canada [

16], Japan [

81], and South Korea [

82]. It is obvious that respondents earned higher educational credentials in Bangladesh. However, such educational credentials were not often recognized in the USA labor market; thus, it was challenging for the respondents to secure a suitable job.

Existing literature suggests that immigrants with prior business experience or business education tend to initiate business ventures in their host country [

83]. Among the surveyed respondents, 28 respondents had exposure to different types of businesses back home in Bangladesh before their immigration to the USA. Such businesses ranged from grocery enterprises to tutoring centers. They largely came from middle-class families in which the family heads ran different businesses to support the family. The types of business the respondents and their parents operated in Bangladesh were often different from those they operated in the USA, with the exception of four cases. For example, in one case, the family had a bookstore and printing press in Bangladesh and, upon immigration to the USA, the respondent opened an ethnic bookstore in Jackson Heights, New York, which is now a highly popular bookstore in the Bangladeshi immigrant community. In another case, a respondent’s family was involved in the garments business. After immigration to the USA, he tried his luck in many other businesses and finally ended up back in the garments business. In the third case, the respondent’s family ran a tutoring center in Bangladesh, providing her with a foundation to open a center in the USA.

Insertion into the local economy demands considerable familiarity with the various aspects of the business and relevant experience, which usually comes with time. We examined immigration timelines and noted that 26 respondents immigrated to the USA between 1990 and 2000, and only four respondents immigrated between 2011 and 2020. Therefore, it is probable that most respondents were early immigrants who had extensive experience living in the country. Living in the country made it easier for them to get legal immigration status. Of the surveyed 50 respondents, 36 held a USA passport, and 13 had permanent residency. One respondent held a Canadian passport with legal resident status in the USA. Thus, all respondents had legal status in the USA. However, this is not surprising because conducting business requires various official documents that can only be secured after acquiring legal immigration status. A question about whether respondents wanted their children to participate in their business in the USA yielded interesting responses. Nineteen respondents did not want to see their children in their own business, whereas 20 respondents saw their business as a potential occupation for their children. In some cases, their children were already in the business, helping and learning the operational aspects. However, many of these respondents commented that they would prefer to see their children opening other businesses that are socially and economically more rewarding.

6. Circumventing Resource Constraints

Arranging the financial and other resources to launch a new business is undisputedly one of the biggest hurdles for new immigrants. It takes time to build up savings, experience, and business networks. This process of resource mobilization will remain ambiguous without an examination of immigrants’ skill acquisition, time taken to start the current businesses in the USA, and previous occupational paths. Immigrants did not start businesses immediately after their arrival in the USA.

Figure 3 shows the years of arrival in the USA and the years when they started their current businesses. Indeed, on average, each respondent took nearly 10 years to start a business of their own. Eleven respondents started their businesses at between 15 and 25 years of residence in the USA. However, in 10 cases, the immigrants embarked on a business venture within two years of arrival in the USA. These immigrants were exposed to family businesses in Bangladesh and possessed substantial financial capital to start a new business, an issue discussed further in the following paragraphs.

Hardly anyone chooses to invest in a business without prior exposure and experience. This is why we inquired about the previous occupations of respondents and noticed an interesting continuation of job experiences and aspirations during the shift from wage employment to self-employment. Twenty-one respondents continued in the types of occupations they were used to having as wage employees for a certain period. They familiarized themselves with the respective businesses, learned the skills, saved the capital, and later opened their own businesses. Some of the respondents did not choose the same business, but one that was somewhat similar, such as moving from McDonalds to Subway or from a grocery store to a convenience store. Seven respondents reported starting businesses similar to those in which they worked as employees.

The shift from wage employment to self-employment also suggested that these respondents secured some personal savings and were somewhat confident in their ability to start a business of their own on foreign soil. Considering the occupations and accumulation of personal savings, it was expected that personal savings would dominate the sources of start-up capital. Personal savings—either from wages earned in the USA or from disposition of properties in Bangladesh—were the sole source of start-up capital for 12 respondents. The assets they had in Bangladesh were slowly disposed, and the cash was transferred to the USA. In addition to securing cash transfers from their home countries, they also saved their incomes in the USA over time to invest in their businesses. Some respondents took partnership as a strategy to circumvent resource constraints.

Of the surveyed 50 entrepreneurs, 20 of them started their current business jointly with other Bangladeshis, usually with friends and/or relatives. When they started the businesses jointly with others, the sources of start-up capital were predominantly their personal savings and small loans from banks and other sources. In one case, the respondent started the business as a joint venture, but later became sole proprietor after settling the initial investment with his partners. Studies on Bangladeshi immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada, South Korea, Japan, and Saudi Arabia did not report the presence of widespread partnership in business [

76,

81,

84]. One of the reasons for forming partnerships in the USA is probably the high material and labor costs and the level of unemployment among immigrants. Business partners tend to work in the same business venture and draw salaries in addition to profits. Thus, their businesses become a source of employment for themselves as well.

Still, some respondents employed different sources—such as friends, relatives, bank loans, and savings—to generate start-up capital for their businesses.

Figure 4 presents the contribution of different sources to the start-up capital of the surveyed respondents. In essence, 36 percent of respondents arranged their start-up capital from a single source: for 24 percent from personal savings, 10 percent from bank loan, and 2 percent from family sources. The remaining 64 percent used two or more sources, such as 20 percent from personal savings and family sources, another 20 percent from personal savings, friends and partners, 8 percent from friends and partners, and the remaining respondents from a combination of sources, such as savings, bank loan, partners, and family sources. The contributions of family members (siblings) were significant; 21 respondents had close family members (siblings) living in the USA due to family visas. However, personal savings remained the major contributor. We found four cases in which bank loans were the sole source of start-up capital.

7. Nature of Immigrant Businesses in New York

The emergence of immigrant businesses are shaped by the opportunity structure, that is, market conditions and access to ownership. There must be demand for businesses that are accessible to immigrant entrepreneurs. Market conditions tend to favor products and services necessary for co-ethnic, co-national, and co-regional groups. To take advantage of such conditions, businesses must be situated to serve a wider market. The emergence of different categories of Bangladeshi enterprises makes it obvious that U.S. market conditions are favorable for Bangladeshi businesses.

Figure 5 presents various types of businesses that Bangladeshis are operating in predominantly Bangladeshi-dominated areas. The businesses surveyed include groceries, restaurants, cultural outlets (e.g., those selling ethnic books, handicrafts and/or newspapers), catering, women’s apparel, used car businesses, electronics shops, real estate brokers, travel agencies, photocopies, mobile phone, and ready-made garment (RMG) outlets. Some businesses primarily serve the needs of co-nationals, and some cater to broader regional immigrants, such as the South Asian market, or a broader immigrant market. Although we found overlapping and sometimes difficult to categorize ethnic and mainstream markets in some cases, we discussed different types of businesses based on this broad classification for convenience.

Of the businesses that emerged to predominantly serve the Bangladeshi community, grocery stores, restaurants, salons, travel agencies, ethnic newspapers and bookstores, educational coaching centers (tutorial centers), income tax filing services, and real estate brokerages are noteworthy. The groceries surveyed mainly targeted the Bangladeshi community; however, they usually procured and sold products of Bangladeshi and South Asian origin, especially Indian and Pakistani products, such as various culinary and food items, in addition to many other products unique to Bangladeshis, such as various types of fish and vegetables. Restaurants emerged as the second most prevalent business venture for these entrepreneurs. Since Bangladesh is predominantly a Muslim country, such restaurants do not serve pork, and this allows the restaurants to expand their clientele beyond even South Asians. Ethnic newspapers also deserve attention. Newspapers tend to showcase community activities and news featuring both Bangladesh and the USA. Shops that sell cultural products, such as handicrafts and music, and Bengali books fill an important market niche by serving the community in New York and beyond. Housing and transportation constituted two unquestionable needs for every immigrant family. A few respondents started real estate and used car enterprises to serve the increasing demand for housing and private transport. Since both businesses require considerable financial investment, some of them also started financial consultancy and brokerage services (securing bank loans) in response to market needs.

Bangladeshi entrepreneurs penetrated markets outside of the immigrant entrepreneur mainstream by opening businesses such as electronic product shops, mobile phone and repair shops, pizza shops, used car businesses, driving centers, convenience stores, street food outlets, petrol stations, and pharmacies. Enterprises that offer tax filing, financial consultancy, and immigration services experienced a strong demand for their services, especially from new immigrants. Shops for electronic products, mobile phones, and repair services, and convenience stores serve a wide variety of clienteles, especially in the low-end market. There was a high concentration of Bangladeshis in the pizza restaurant industry in New York and nearby states. Exposure to the operation of pizza restaurants allowed some of them to franchise different pizza brands and run them independently. We noticed a similar arrangement for Subway. Street food is famous for cheap, quick service, and street food providers are usually located in convenient areas, such as tourist spots, subway stations, and other high-traffic places. Pharmacies are another interesting business venture in New York. We identified several pharmacies run and owned by Bangladeshis.

In addition to the nature of businesses, this study also investigated the employees and their ethnic origins. The businesses that this study examined had 238 employees in total; each business had an average of 4.95 employees. Eighty-one per cent of the employees were working full-time, and 19 per cent were working part-time. Nearly 26 per cent of the employees were female. Female employees were more likely to work part-time. Although these businesses were primarily run by employees of Bangladeshi origin, several businesses employed people from other nations, such as India, Pakistan, Mexico, Spain, and various countries in Africa. In total, 14 out of 47 businesses had hired other nationals. The businesses that hired immigrants of other national origins included restaurants, pharmacies, Subways, groceries, pizza restaurants, salons, auto workshops, and petrol stations. It is obvious that a new type of immigrant enterprise is emerging in which the businesses, the clienteles, and even the employees are of diverse origins, representing a departure from earlier forms of ethnic business.

8. Innovative Practices

Immigrant retailers, wholesalers, service providers, and exporters confront cut-throat competition in their businesses and employ innovations in products, sales, and distribution to make their businesses different and rewarding.

Figure 5 presents the estimated percentages of the ethnic origin of clientele for different enterprises as reported by the respondents. We broadly categorizes two groups: Bangladeshi clientele and non-Bangladeshi clientele. The non-Bangladeshi category included people from South Asian, Southeast Asian, African, Middle Eastern, Latin American, and European background. This broad categorization was offered to demonstrate how immigrant entrepreneurs use both ethnic and non-ethnic businesses (e.g., petrol station) to attract non-ethnic clientele to their businesses by employing innovative practices in products, sales, and distribution.

Product innovation was a decisive factor in immigrant businesses because business owners must compete with other co-national and co-regional businesses and attract a wider clientele. We investigated product innovations in the two most common first businesses for immigrant entrepreneurs: grocery shops and restaurants. This study included 10 grocery shops and six restaurants located across New York City. Groceries tended to showcase a wide range of products, including vegetables, fish, and meat (frozen and unfrozen), culinary items, confectionary items, dairy products, and cosmetics. Grocery owners procured supplies from different wholesalers who dealt in products from South Asia, East Asia, and even Turkey and some North African countries. These groceries did not source products from Bangladesh alone. Procuring various high-demand products from diverse sources was a used strategy to reach different immigrant groups from Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa (MENA) and thus widen the clientele base. It is important to note that immigrants from the MENA region are usually Muslim, and grocery owners are aware of the demand for halal food. Thus, these groceries served new immigrants from Asia and MENA in New York and nearby states.

In restaurants, product innovation finds its expression in the art of cooking. Bangladeshi immigrant entrepreneurs primarily ran two types of restaurants: one dealt with exclusively Bangladeshi customers, and the other served South Asian immigrants and beyond. It is important to note that the owners of all six restaurants under study worked in restaurants on different capabilities, and they had acquired valuable skills suitable for running a business successfully. In general, owners of restaurants tended to hire experienced chefs and offer unique dishes, and their personal exposure to restaurant businesses helped them acquire these skills and connections with others. In the first type of restaurant, owners offered different types of Bangladeshi dishes with an astute sense of regional variation (e.g., dishes popular in the Chittagong, Sylhet, Comilla, Barishal, or Khulna regions of Bangladesh). In the second type of restaurant, the owners usually targeted high-end customers who are likely to spend more to taste authentic South Asian cuisines. These restaurants are usually visited by both South Asian elites and other mainstream customers who like to have a lunch or dinner surrounded by authentic South Asian ambiance.

Innovations in used car businesses included the combination of used car sales and repair shops. Used Japanese cars are in high demand, so many businesses procured used Japanese cars in bank auctions after car loan payment defaults, then sold them to community members and beyond. The customers of these businesses were not necessarily all Bangladeshi in origin. They performed better than many other non-Bangladeshi competitors because they added service packages from their own workshops, usually at lower prices than outside workshops, creating a “two in one” deal for potential car buyers. A few respondents were involved in mobile shops with repair facilities. The owners first worked in the same field for a few years and then opened a shop in a convenient location. To attract wider clientele, they sold mobile sets and offered repair services, including sim card changes.

Cultural products—such as handicrafts, Bangladeshi art, and portraits of national heroes, and Bengali books—constituted authentic cultural products sold in shops in Jackson Heights. Handicrafts are procured from Bangladesh directly and are sold year-round. However, they are in high demand and sell for higher prices during national events of Bangladesh, such as Independence Day (26 March), Victory Day (16 December), and Language Martyrs’ Day (also called International Mother Language Day, 21 February). Book shops offered a wide range of collections written by Bangladeshi scholars as well as Bengali scholars from West Bengal, India, thus serving wider Bengali clienteles in the USA. Some entrepreneurs were found to be running Subways and pizza restaurants, serving the mainstream market. The owners of these restaurants worked in pizza and Subway shops for a number of years before later securing franchises to run their own businesses. As they had worked in such restaurants previously, they were aware of the operations and logistics required to run the business successfully. The respondents reported that the profit margins for running a pizza or Subway restaurant were limited. However, they aimed to own more than one outlet to secure higher returns.

We included three salons in our survey. Like pizza restaurants and Subways, salons are low-profit businesses; the price for each cut ranged from $8 to $12. Although salon owners targeted more clients by opening in convenient locations, they also aimed to establish more locations for higher profits. They added other high-value services along with haircuts, such as washing, coloring, styling, and massage. Two unusual types of immigrant business run by two female entrepreneurs, namely driving schools and tutorial centers for school children, deserve special attention here. The owner of the driving school worked in a driving school in New York City for a few years, and later realized that there was no Bangladeshi driving school in New York City. She opened the driving school and introduced a Bengali translation of the driving instruction books at her center. She was able to attract Bangladeshi and, later, other South Asian immigrant women in a short span of time. Although the driving school was owned by a female Bangladeshi immigrant, the school was not a female driving school as such. Male learners also took lessons at this driving school. A female educator was running a tutorial center for primary and secondary students in New York. Her family was involved in a similar enterprise in Bangladesh. Upon immigration to the USA, she realized there was a demand for private tutoring among immigrant children, many of whom were struggling to cope with American school standards. She started with a few Bangladeshi students and later expanded the center to accommodate South Asians and others.

Innovations in sales and distribution also distinguished immigrant enterprises. Three strategies were particularly common in the literature: spatial, temporal, and modality strategies [

56]. Spatial strategy was widely observed among our surveyed enterprises; that is, businesses were opened at convenient locations, where there was a high concentration of other ethnic businesses and/or similar business types. From the entrepreneurs’ perspective, having similar businesses in the same complex or nearby builds trust among customers, and more customers tend to visit these locations for convenience. As a barber shop owner reported, “price is fixed, and we cannot charge a higher price; therefore, what we needed was to get more customers. People do not have time to wait for several hours for a haircut. In our shopping complex, there are three salons, and we are doing good businesses”. The same logic was communicated by owners of printing shops, gadget shops, and clothing and apparel shops.

Subway restaurants, gadget shops, and convenience stores were usually located near public transport access. However, pizza shops were not found as frequently at high-rent roads or complexes. One of the reasons given by respondents was that pizza is considered a delivery product. People do not want to walk or ride to get a pizza; they prefer to order for home or office delivery. In contrast, pharmacies, restaurants, handicraft stores, and groceries are usually located in areas that are easily accessible via public transport. Although many businesses tend to cluster at specific locations, there are some businesses that do not follow such spatial logic, such as car repair shops, used car showrooms, and real estate agencies. These businesses tend to be placed in low-rent areas to reduce expenses.

Temporal strategy was historically used by ethnic businesses because they tend to rely more on unpaid family labor. Most of our surveyed respondents were running businesses that relied on part-time and full-time employees. Sometimes adult members of the family offered a helping hand, but it was not found as a cost-saving measure on a regular basis. Shops followed standard opening and closing hours; however, some businesses, such as Subway and pizza restaurants, remained open for longer periods, and respondents ran a pharmacy that operated 24/7. With regard to modality strategy, some respondents employed sales and distribution modalities that differed from convention ones with services on sites alone. Some groceries and restaurants offered take-away and home delivery services in which customers placed orders via telephone or an online app, especially for customers who lived far away, including areas outside New York, such as Connecticut and New Jersey. Thus, different types of Bangladeshi immigrant businesses employed different innovative practices to differentiate themselves from competitors.

9. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Espousing the integrative framework of Waldinger et al. [

49] and the innovation [

54], and the breaking out strategy of Engelen [

56], this study discussed the emergence of entrepreneurship in a contemporary immigrant group in New York. This study investigated two issues: the emergence of entrepreneurship among new immigrant groups and the importance of innovation in small immigrant businesses.

To address the first issue, we elaborated on how predisposing factors, resource mobilization, market conditions, and innovation interact to make new immigrant enterprises through a case study of Bangladeshi entrepreneurs in New York City. As discussed earlier, existing studies tend to study either group characteristics or opportunity structure in the host country [

1,

2]. We have taken an integrative approach to immigrant businesses by combing the socio-demographic features of Bangladeshi entrepreneurs with the opportunity structure in the host society. This approach enabled us to document the complex interplay of socio-demographic attributes, ethnic bases of resource arrangements, demand for ethnic products and services, and, finally, innovation practices in a more nuanced manner.

This study showed that Bangladeshi immigration to the USA primarily grew due to the Diversity Visa program in the 1980s and the subsequent family quota system. In the absence of labor market-driven selective immigration, such as a skill-based immigration program like the one found in Canada, most Bangladeshi immigrants used two channels for legal immigration to the USA: fortune-driven diversity visas and self-feeding family immigration visas. As a result, the educational credentials, professional skills, and experience necessary to secure relatively stable, professional jobs in the U.S. economy remained scarce among this new group, providing a motive for opening new businesses. The opening of new businesses involves two preconditions: financial capital and relevant business experience.

This study showed that Bangladeshi immigrants worked in different small businesses and gained experience before they started their businesses, often opening businesses similar to those in which they were previously employed. They saved and invested their savings in the businesses, and, when the savings fell short, they secured start-up capital from their friends, relatives, and banks. In addition, they sometimes formed partnerships to circumvent capital and skill constraints. Regarding resource mobilization, the existing studies emphasized the importance of financial capital and social capital [

43,

44,

85]. We reported that resources may also constitute business skill formation, as immigrants lack the financial and social capital and skills for running a business in a new host country. Most Bangladeshi immigrants worked at various businesses to gain operational skills, sharpen their business acumen, and accumulate start-up capital for new enterprises. Thus, this study reported a two-pronged strategy of resource formation and mobilization for Bangladeshi immigrant entrepreneurs in the USA.

The structural approach to immigrant businesses stresses the demand for ethnic goods and services as a critical factor for the emergence of immigrant businesses [

5,

40,

48]. This study showed that the emergence of immigrant businesses was also contingent on the opportunity structure. This paper reported on the demand for ethnic goods and services, especially among burgeoning Bangladeshi communities in New York and nearby states, such as Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The emergence of a wide range of Bangladeshi enterprises suggests robust demand for immigrant goods and services in the market. As a gateway city, New York has emerged as a center of attraction for this emerging community to live and work, generating a substantial demand for ethnic goods and services. The demand was also fueled by the community members living in states near New York, who often make weekend visits to New York City and make purchases from immigrant shops while visiting their relatives and friends in the area.

Existing studies tend to argue that access to ownership largely depends on two factors: the number of vacant business ownership positions and government policies toward immigrants [

86,

87]. For instance, Kim found that Korean grocery store owners have taken over from Jewish or Italian proprietors [

88]. However, our surveyed respondents did not assume the business ownership from some other groups. They identified the market niche and opened new businesses of their own. Thus, the business vacancy hypothesis does not fit in the case of the Bangladeshi immigrant entrepreneurs. Access to legal ownership of immigrant businesses is also affected by government policies [

49]. Our surveyed immigrants secured legal status to live and work in the country by gaining citizenship, permanent residency, and work permits. As a result, the individuals we surveyed reported minimal legal barriers to opening businesses.

The second issue dealt with innovation in immigrant businesses by dissecting the innovative practices of immigrant entrepreneurs. The mainstream literature on entrepreneurship extensively addressed the issue of innovation in businesses [

89,

90]. We argued that the literature on ethnic entrepreneurship has largely overlooked the importance of innovation in small businesses. We showed how innovation in products, sales, and distributions attracted compatriot and non-compatriot clienteles and made their businesses rewarding. We demonstrated that, notwithstanding their marginal nature, immigrant businesses grew and prospered because of the ingenuity of immigrant entrepreneurs and their willingness to adopt innovative practices to make their businesses different and rewarding. This paper showed that immigrants employed different innovative strategies for product offerings, distribution, and sales. They introduced new products from their home countries and other regions, as reported for groceries and restaurants, thus expanding their clientele beyond the Bangladeshi community. Product innovation was also reported in diverse businesses, such as salons, used car businesses, media, and print shops, travel agencies, tutorial centers, and driving schools.

Waldinger et al. advanced two concepts in their study of ethnic entrepreneurship: “economic assimilation thesis” and “enclave spatial logic” [

49]. The economic assimilation thesis suggested that immigrant businesses gradually lose their immigrant identity and thus turn into mainstream businesses. However, Engelen argued that the economic assimilation thesis does not adequately consider innovation in immigrant businesses [

56]. Our study reported that immigrant businesses attracted both compatriot and non-compatriot clienteles. While some businesses are increasingly attracting the mainstream non-compatriot clientele, the origins of such non-compatriot clientele are fascinating; they are often people of Asian origin. They are more often religiously Muslim clienteles from the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. In addition, some businesses were attracting more non-compatriot clientele. However, most businesses also maintained a substantial percentage of compatriot clientele at the same time and thus retained a sustained ethnic appeal to the broader community members. We viewed the reason behind this entrepreneurial success as lying in the adoption of innovative practices in their businesses. Rahman and Lian, in their study of South Asian immigrant businesses in Japan, also reported a similar trend [

81].

Engelen argued that spatially oriented strategies were relevant for some entrepreneurs, but not for others [

56]. In a similar vein, Bangladeshi immigrant businesses met a sharp break with “spatial logic” because these entrepreneurs introduced innovative marketing and distributing strategies against the traditional notion of “spatial logic of the ethnic enclave”. For instance, we reported that some enterprises offered service innovations such as home delivery, take away, two-in-one services, and buy now and pay later services, undermining the traditional spatial, temporal, and modality strategies. A similar trend was also reported in the studies of immigrant entrepreneurship in South Korea and Canada [

76,

82].

The surveyed immigrant entrepreneurs are ingenious in widening and deepening their clientele base, attracting compatriots and non-compatriots, and moving beyond the ethnically dominated locality. Thus, the Bangladeshi immigrant enterprises differed from the classic ethnic business pattern of owning a small, often vulnerable enterprise in a neighborhood with a strong ethnic concentration and banking overwhelmingly on compatriot clienteles and networks [

3,

83]. Thus, innovation has made these enterprises different and rewarding, and transformed them into businesses that illuminate the breaking out process for new immigrant entrepreneurs.

This study attempted to provide critical insights for understanding the development of immigrant entrepreneurship among Bangladeshi immigrants in New York. There is a dearth of research on new immigrant groups and their businesses in the gateway cities in the USA. Although this study attempted to contribute to our understanding of this complex phenomenon, more work is needed to document the emergence of ethnic businesses among other new immigrant groups in the USA to compare their experiences. Among the lines of research to be developed, it would be interesting to study: (i) why new immigrants perform marginal business activities and escape to entrepreneurship; (ii) female participation in immigrant businesses; (iii) intergenerational patterns of immigrant businesses; (iv) business activities of different new immigrant groups from Asia, Africa, and Latin America; (v) mechanisms to help new immigrant businesses through various policy initiatives at the state level; and (vi) the feasibility of designing corporate social responsibility policies in New York that would help new immigrant groups develop more entrepreneurial ideas.