1. Introduction

Recent times have observed an increased interest in the potential of key technologies such as big data in enabling organisational agility (OA) within complex, dynamic, and innovative business environments [

1,

2,

3]. OA differs from organisational change in that the former shows how leaders can become proactive and transform themselves when faced with unpredictability, while the latter deals with leaders driving top-down change [

4]. Hence, OA is conceptualised as a dynamic capability that operates at the organisational level to enable an organisation to cope in uncertain environments [

5]. In addition, agility is seen as a crucial capability to detect and seize competitive opportunities to generate innovations [

6]. Indeed, a recent investigation of Amazon’s global growth is linked to its agility capability [

7]. In summation, OA helps leaders and managers to build an ability to sense environmental changes and proactively respond to them [

8]. That is why agility is a desirable goal for any innovative organisation.

OA requires a shift from managerial control mindsets to “managing by all” (p. 118 [

9]). Hence, managers are expected to care about their employees and empower them to build firm-level capabilities to deliver agile capacity to firms [

10,

11]. This mindset, however, does not happen by itself. Managers should further embrace a learning culture at the organisational level [

5], where this so-called organisational learning culture (OLC) is considered “a collection of organisational conventions, values, and practices that encourage employees in an organisation to develop critical skills, knowledge, and competence through continuous learning processes” (p. 584 [

12]). Indeed, given such an intuitive significance of the concept of OLC and OA in delivering better performance outcomes for firms, there has been a complementary surge in research on the topic [

5,

8], though it seems the resultant impacts of OA and OLC on firm performance are not so clear [

13,

14].

For instance, earlier studies have recognised that an effective OLC can incur some positive performance implications for organisations [

15]. However, when investigating firm performance from both the financial and non-financial perspectives, some found a direct and positive link between the OLC and organisational differences between the two [

16]. Here, there appeared to be no direct link between the OLC and financial performance instead of occurring through non-financial performance vis-a-vis employee, customer, and supplier performance [

16]. This is something more recent work has also come to find in the sense of employee empowerment mediating the impact of the OLC on organisational performance [

17]. Conversely, a study [

16] found that a direct impact could be observed between the OLC and financial performance. More recent findings also provide some insight into the complexity of understanding the organisational implications of an effective OLC by demonstrating an indirect link through various other cultural norms, including innovation culture (when it comes to innovation performance) [

18,

19] and digital culture (when it comes to sustainability performance) [

20], to name a few. Indeed, such a challenge is compounded when introducing the notion of OA, particularly as it is characterised as a kind of organisational capability [

21]. As will become evident throughout this work, shining a light on the link between organisational capabilities, learning culture, and organisational performance remains an open task and one which we endeavour to key into with the help of big data as a complementary phenomenon.

To help deal with these challenges, this paper adopts the notion of firm growth as a performance metric. This choice helps us avoid the pitfalls associated with the adoption of financial and non-financial metrics and also induces the notion of time, a contributing factor in the issues associated with differing financial performance implications [

16]. In addition, this paper draws on dynamic capabilities theory, a widely used organisational theory reflecting the firm capabilities used in transformation [

8], to help make sense of the complex nature of the relationships between knowledge-based and capability-based constructs [

15]. More specifically, we adopt a hierarchical stance to dynamic capabilities, where lower-order (ordinary) capabilities help organisations perform day-to-day functions whilst higher-order (dynamic) capabilities help induce change in an organisations’ resource base [

8,

21]. This hierarchy ultimately helps us to demonstrate how OA, as a higher-order dynamic capability, presents a valuable capability in achieving a sustained competitive advantage [

22].

In adopting this perspective, we also recognise that dynamic capabilities are insufficient on their own; that is, to understand how they impact firm performance, the influence of lower-order capabilities should also be considered as a “dynamic bundle” [

23,

24].

To this end, we introduce big data capabilities (BDC), or digital technologies to manage large volumes of data [

25], as a lower-order capability that helps shed some more light on the ambiguous relationship among OLC, OA, and organisational performance. Recent studies have demonstrated the link between digital technologies and dynamic capabilities needed for agility [

2], perhaps more so in the context of agility in particular [

3,

26]. However, these studies do not consider distinguishing how the specific technologies might have varying impacts. Such an omission puts a damper on the understanding of how organisations can generate technology-related strategies with the aim of building agility [

26]. In this paper, we delve into big data technologies, though as described next, making sense of their use in practice, particularly in grasping their place in an organisation’s resource pool, leaves much to be desired.

The results appear to be mixed when it comes to contemporary work that investigates the interaction of big data capabilities and dynamic capabilities. For instance, some authors specifically refer to BDC as a dynamic capability in and of itself, having a significant influence on how organisations maintain the capability to adapt to changing circumstances [

27]. Others suggest that BDC is a function of better management practices [

28,

29], while others view BDC as a lower-order capability [

30,

31]. Again, relying on dynamic capabilities theory, the expectation is that BDC can behave in an additive (complementary) fashion. BDC enables the transformation of organisational culture into actionable capabilities for ongoing organisational renewal, thus also acting as a conduit that can link the knowledge-based construct of OLC to higher-order dynamic capabilities.

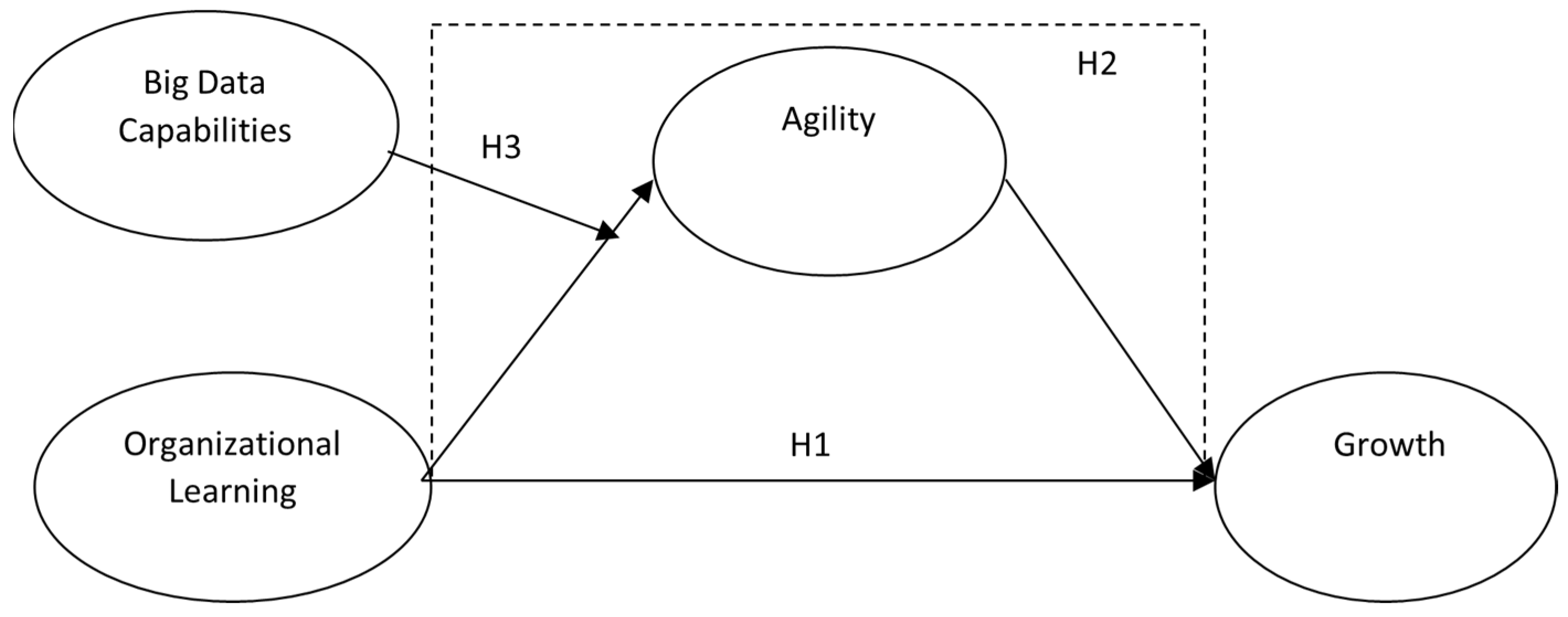

Based on this, our contribution to the theory is twofold. First, we shed some more light on the nature of the interaction effects between OLC, OA, and firm-level performance by introducing the notion of “growth”, which induces a time-based perspective. Secondly, we key into discussing the complex and ambiguous nature of interactions between knowledge-based and capability-based phenomena with a firm-level performance by introducing a dynamic bundle consisting of OLC, OA, and BDC. Thus, our intention is to contribute toward a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between knowledge-based and capability-based phenomena and ultimately provide some insights for the practical adoption of big data technologies to put OA and OLC to work in organisations.

In order to achieve this, the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 focuses on the extant literature and develops hypotheses to link the organisational learning culture and growth performance through OA’s mediating impact.

Section 3 describes the data and the research method, whilst

Section 4 presents the analysis results, followed by a discussion in

Section 5. The paper ends with the contributions to the literature, a summary of the limitations, and some suggestions for future research.

3. Research Design

The following figure visualises the research study design (See

Figure 2). Steps 1, 2, and 3 in the research method diagram have been mentioned in the previous parts, while steps 4 and 5 will be described in more detail in the following sections.

3.1. Measures

Multi-item scales for OLC and OA were adopted from prior studies to measure the constructs and test the hypotheses mentioned above. Growth and big data competency were measured by asking the respondents directly, as shown in

Appendix A. Each construct was measured using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

In this paper, the OLC is an independent construct. A scale consisting of 6 items was adapted from the Dimensions of the Learning Organisation Questionnaire (DLOQ) [

52]. One sample item is “In my organisation, people help each other learn.”

To measure the companies’ OA, an OA scale (6-point Likert scale) consisting of 3 dimensions—OpA, CA, and PA, each having 2 items—was adapted from Felipe et al. [

5] and Sambamurthy et al. [

6]. Some examples of the performance scale items are as follows: “Often rethinks their business model and creates their digital attack businesses” (OpA); “Thinks end-to-end about where digital efforts can produce a step-change in value for customers” (CA); and “Has an open structure for collaboration, and different organisations and processes for radical and incremental projects” (PA).

To measure the BDC, we asked the respondents to evaluate their companies’ level in understanding big data analytics strategically and operationally on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Finally, for measuring organisational growth, we asked the respondents to rate the revenue growth performance of their businesses over the last 3 years, on a 5-point Likert-type scale, including “0% or less” (1), “1–5%” (2), “6–10%” (3), “11–20%” (4), and “over 20% (5)”. Hence, this study utilised perceived growth (PG) as its performance measure.

Although not the focus of our study, turnover value was included as a control variable, as it may potentially mitigate any spurious interpretations of the findings. The respondents chose 1 of the 5 turnover values their company achieved in 2016: “less than AUD 10 million”, “AUD 10.1–100 million”, “AUD 101–250 million”, “AUD 251–500 million”, and “over AUD 500 million”, where m refers to million. Then, their answers were coded as a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “less than AUD 10 million” (1) to “over AUD 500 million” (5).

Even though the extant literature suggests that the firm size or other characteristics can be involved as control variables for firm-level analyses, international business and marketing studies are prone to endogeneity issues [

53]. Specifically, many researchers emphasise the routine consideration of endogeneity in international studies [

54,

55]. Moreover, some researchers even argue that PLS-SEM does not allow endogeneity to be addressed [

56,

57]. According to Hult et al. [

54], between 2008 and 2017, none of the 43 reviewed PLS-SEM articles published in the

Journal of International Marketing,

International Marketing Review, and the

Journal of International Business Studies—the three highest-ranked international marketing journals—tested for endogeneity. Since our study was conducted on a national sample (i.e., Australian companies), and we used the PLS- SEM technique, endogeneity was not an issue for our research.

3.2. Sampling

The research design included a sample of Australia‘s leading 247 companies whose leaders belonged to a professional organisation called the “CEO Circle.” This group organises confidential networking for individuals working in CEO and C-level roles [

58]. Since our study focused on leadership perspectives regarding culture, agility, and growth of firms, the “CEO Circle” provided access to individuals in CEO, C-level, and managing director roles across a diverse cross-section of organisations within Australia.

First, the CEO Circle member managers were contacted by telephone, and the aim of our study was explained to them. Of the 247 firm managers contacted, 223 agreed to work with this study, and eventually, 185 completed the questionnaire. The original data collection took place in 2016, and it included extra subsections covering strategy-focused questions. The initial data analysis was published as an executive report in 2017 [

58]. This study derived from the survey by dropping the disruptive technology strategy section and focusing on questions related to organisational learning culture, agility, growth, and big data capabilities (see the survey questions in

Appendix A).

After removing the surveys that had no growth data, the study ended with usable data from 138 companies. The respondents were 77 CEOs (56%), 21 C-Level executive directors (15%), and 40 other non-executive and business unit heads. In terms of turnover, 31% (43) of the firms had an annual turnover of over AUD 500 million, while 24% (34) had between AUD 10.1 and 100 million, 19% (26) had between AUD 101 and 250 million, 14% (19) had between AUD 251 and 500 million, and 11% (16) had less than AUD 10 million. Our study represents a wide range of small, medium, and large companies. Moreover, 18 of the participant firms (13%) were operating in the manufacturing industry, while 18 (13%) were in finance and insurance, 14 (10%) were in retail, 12 (9%) in were ICT and technology, 12 (9%) were in accounting services, 11 (8%) were in health, and the rest (53 companies) were in other sectors.

3.3. Assessment of Common Method Variance

In order to test for common method variance (CMV), we used Harman’s single factor [

59] by exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with all variables loaded onto a single factor without a rotation. The new common latent factor explained only 21.73% of the variance, significantly less than the cut-off value of 50%.

Kock [

60] suggested that a model with greater than 3.3 variance inflation factors (VIFs) signals a CMV issue. The results of our VIF analysis (as seen in

Table A1 in

Appendix B) show that the VIF values ranged between 1.054 and 1.712 (i.e., the values were lower than the proposed threshold of 3.3). Accordingly, our model did not seem to be affected by common method bias.

5. Discussion

Knowledge is arguably one of the most important resources organisations have under their control, not the least when adapting to (or inducing) changes in the marketplace [

71]. Thus, effectively creating and disseminating this knowledge throughout an organisation is a core capability for sustained competitive advantage [

72]. However, this is not straightforward, as such a capability often needs to be built, nurtured, and ultimately embedded into the way an organisation conducts its business [

8] (i.e., organisations should hold a learning culture if they are to survive in the long term).

Our results support the premise that an OLC is a key yet insufficient ingredient in an organisation’s pursuit of continuous growth. Like others (e.g., [

73]), we found that the value of holding an OLC only came into play through the development of dynamic capabilities. Then, the OLC ultimately led to organisational performance, thus providing further evidence to support the viewpoint of learning mechanisms, such as the OLC, giving rise to higher-order dynamic capabilities [

40]. However, when it comes to an understanding of the foundations (such as BDC) that support this process of capability building, our results pose some interesting conclusions.

In our case, BDC presented themselves as enablers for successfully transforming an effective learning culture into actionable capabilities for inducing and adapting to change. The results suggest that, aside from being an important precursor for dynamic capabilities, BDC hold additive (complementary) qualities by bolstering the knowledge creation and dissemination activities stemming from an OLC, which are then used to help with strategic choices in maintaining evolutionary fitness. This resembles a so-called “dynamic bundle” [

23] that helps to further explicate the still ambiguous role (and interdependencies) of lower-order capabilities (BDC) and higher-order dynamic capabilities (OA), though it also includes a knowledge-based element of the OLC, thus further demonstrating a successful integration of disparate views on organisations [

73].

Such a bundle of capabilities, culture, and learning mechanisms also helps demonstrate how capabilities can be embedded and modified through an organisational culture, something that remains difficult to grasp [

74]. As is still the case, (learning) culture seems to be one of the most challenging themes for agile organisations [

75], particularly when shifting from an exploitative mode of operation to one that is more exploratory [

38]. Often, this shift would involve introducing conflicting goals, values, and practices that would have to coexist depending on the strategy being adopted. Our study, like most, reinforced the power of an effective learning culture in leveraging change. However, we also demonstrated how BDC can potentially resolve (or leverage) such an organisational paradox. Indeed, how BDC should be adopted in times of learning or organisational change to cope with these conflicting themes is still a key question involving a wide range of contingencies, including, for instance, environmental dynamism and technological change [

76,

77]. Though our data could not directly substantiate this impact, we provided preliminary insight into this as a platform for future studies.

6. Conclusions

This paper observes the relationships among the OLC, OA, BDC, and growth performance. The search for how agility delivers better firm performance has recently been a popular topic [

26]. However, agility does not occur in a vacuum; rather, it is a product of the company culture. Thus, our study offers a model to explain how the OLC triggers a chain effect through its influence on OA, resulting in company growth (behaviour) performance. Consistent with the hypotheses developed in the model, we showed the positive relationship between the OLC and growth performance only through full mediation. Hence, we could confidently highlight that the OLC did not generate growth, strengthening the argument that managers should generate a learning culture to embed attitudes for behavioural change.

This paper considered OA as a desired dynamic capability for companies striving for survival in turbulent environments based on dynamic capabilities theory. Another interesting finding indicated the key role of BDC in amplifying the impact of the OLC on OA. These findings pointed out that firm leadership should facilitate an effective learning environment and build big data competencies through the efficient use of technologies to survive the stringent competition and perform well. Thus, this paper highlighted that building capabilities in organisations, including OA and BDC, could enrich each other and build a solid base to deliver successful organisational growth.

6.1. Implications for Theory

Our study contributes to dynamic capabilities theory in two main ways. First, considering that dynamic capabilities theory is instrumental in understanding organisational performance [

8,

29,

71], our data explains how OA as a dynamic capability affects organisational performance by transferring the OLC into growth (i.e., a construct we adopted to help counter the ambiguous outcomes from financial and non-financial performance metrics). Second, taking on the complex and ambiguous role of BDC in fostering a more responsive and flexible organisation, we demonstrated how BDC can act as part of a complementary “dynamic bundle” [

23,

24], shedding light on the interaction effects between knowledge-based phenomenon (OLC), lower-order capabilities (BDC), dynamic capabilities (OA), and firm-level performance. Indeed, the influence of learning in the dynamic capabilities schema is not so straightforward and leaves much room for refinement [

78]. In line with others [

73], we observed that the OLC acted as a precursor for and facilitator of organisational renewal, going back to the fundamental notion of building dynamic capabilities through learning [

40]. What is interesting here is the fact that BDC (characterised as a lower-order capability) appeared to bolster the efficacy of a learning culture in enabling ongoing organisational renewal, leading to firm-level growth. Thus, BDC did not appear to be a substitute for the OLC and did not disrupt the efforts of a learning culture in building dynamic capabilities. Generally, learning from big data poses significant challenges for organisations, not the least being when it comes to making sense of the learning this technology can bring [

76]. Mastering this capability requires a conscious effort for learning in new and flexible ways [

76]. Thus, perhaps “learning to unlearn” [

79] becomes a characteristic of such a capability. This finding brings it further to the notion of second-order capabilities [

79], the likes of which do not necessarily work to keep the organisation running efficiently (like lower-order capabilities would typically be regarded as performing) but rather help the organisation build first-order dynamic capabilities themselves. Because this runs somewhat counter to the idea of BDC as dynamic capabilities [

27], it would be interesting to observe the interaction effects of BDC on the relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm-level performance outcomes to help provide some more insight into this phenomenon, perhaps proving a fruitful notion for further research.

6.2. Implications for Practice

Concerning practical implications, this study proposes two contributions. First, managers should empower their employees by OA and BDC, with the knowledge that their most important tool to fight dynamic market pressures is, to a large extent, linked to their ability to make effective use of big data. Managing data will improve leadership by bringing workforces on board and equipping them with the necessary capability sets [

36,

80]. This study clearly shows how big data competencies helped to utilise the OLC to become effective in OA.

A second practical implication involves the importance of culture for leadership. Leaders should consider understanding, building, and sustaining a learning culture as part of their leadership roles. They should be better trained in building healthy cultures and aligning culture and strategy [

81]. An abundance of research in leadership and organisational culture [

36,

50,

74] clarifies that building strong cultures can play a significant role in the innovativeness of organisations. Therefore, overlooking organisational cultures can cost organisations and their employees, customers, and stakeholders.

A final remark to managers and leaders within companies is that OA is built over a strong learning culture, so they should consider how to flourish this dynamic capability within their company environments. They might try different structures and human resource practices to build a strong learning culture [

81]. They should also find ways of improving their agility by emphasising the performance of different agility dimensions such as customer, operational, and partnering agility. Understanding nuanced information in each agility dimension could help efficient technology management to create their competitive advantage.

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

A few limitations should be noted, along with questions for future research. First, since using cross-sectional data is one of the significant limitations of this research, questions are raised about the causal direction and purpose of the relationship among the constructs. Even though surveying is considered a standard method for research in the business environment, the method used (only questionnaire) may not provide objective measures and results about the flow of knowledge. For example, it is unclear how the agility within customer relationships, operations, and partnership relationships is a dynamic phenomenon in the management context. Due to cross-sectional data and restricted time issues, scholars should collect longitudinal data.

Second, and probably foremost, the data are self-reported. Even though organisational researchers are not fond of using self-reports, they cannot do without them, as the practical usefulness of those measures makes them virtually essential in many research contexts [

82]. Indeed, self-reports are not as limiting as once commonly asserted [

83]. The extant literature provides evidence regarding the more precise estimates of self-reports than the behavioural measures [

84]. For instance, using self-reported and perceptual indicators versus objective ones is a rising issue in performance measurement.

Many studies have provided empirical evidence supporting a strong correlation between objective and self-reported performance measures [

85]. The present results provide evidence of relationships among the variables. Moreover, to go beyond the hesitations regarding self-reported measures for perceived growth, we also attempted to gather objective measures for growth. However, only 44 of 138 companies publicly shared actual growth data. Hence, we decided to check our results by conducting the same tests on the sample of 44 firms. The results obtained from this smaller sample were very similar to the previous ones, except for the moderating effect of BDC (See

Table A2 in

Appendix B).

Third, this study considered turnover a control variable, while many other factors such as firm size or human resource practices [

14] might play a role in growth. Future studies could enrich the investigation to determine the significant factors that might increase our understanding of the interplay among the OLC, OA, and growth.

Moreover, the sample size was also limited (n = 138). However, since our initial sample comprised 247 companies whose top managers were members of the CEO Circle in Australia, we gathered data from 57% of our initial sample, proving a good ratio. Moreover, we chose the CEO Circle to reach out to senior executives who could direct us in the right direction for the macro-level leadership topics under investigation in this research.

Fourth, our study was conducted in Australia, and it was hard to generalise. Future studies could conduct comparative studies and gather large datasets to allow comparisons and the deriving of theoretical and practical lessons regarding the relationship between the OLC, OA, BDC, and growth.

Finally, this study explored OA’s mediating role as a three-dimensional composite construct, composed of operational agility, customer agility, and partnering agility, on the relationship between the OLC and growth. There is still a lack of consensus regarding the content of OA in the management literature. Different dimensions could be related to OA as a multifaceted concept, thus proving to be an interesting future research topic. Indeed, two findings of this study point out promising future study avenues. First, our finding that the OLC did not directly affect growth is a research question that could prove intriguing for researchers. More studies should conduct empirical studies to cross-examine the explanatory power of OA as a dynamic capability in strengthening the benefits of digital technologies such as big data. Second, this study demonstrates that BDC influences the impact of the OLC on OA as a complementary bundle consisting of lower-order capabilities, higher-order (dynamic) capabilities, and the knowledge-based construct of the OLC. Further research is encouraged to examine the contingencies surrounding their relationships to draw a more fine-grained picture of how individuals use big data to translate organisational culture to a dynamic capability for ongoing organisational change based on innovations.