Establishing a Sustainable Labor Market in Developing Countries: A Perspective of Generational Differences in Household Wage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Empirical Research Design

Data Source and Processing

4. Variable Setting and Descriptive Statistics

4.1. Explanatory Variables

- Work experience (exper.): Given that obtaining accurate data on workers’ work experience is difficult, the paper is based on the work of [9,36]: the actual age of the individual, minus the number of years of education, minus six, is used as a substitute variable for the worker’s work experience. According to Chinese labor laws, if the education level is below junior middle school, people must be at least 16 years old to work; accordingly, their work experience is expressed as age minus 16.

- Marital status (marriage): This paper considers the effects of having a spouse on the income level of workers; thus, the samples marked as cohabitation are classified as those with a spouse. Therefore, marital status is divided into those who are married and those who are not. The former is assigned a value of 1, and the latter is assigned a value of 0.

- Gender (gender): Given that gender wage differences are evident in the Chinese labor market, gender was deliberately considered in the regression, with male respondents assigned a value of 1 and female respondents assigned a value of 0. Owing to the generational differences studied in this paper, gender variables were included in the mixed sample regression model.

- Occupation type (proff): Different occupations may affect the labor income of urban and rural employees in two ways. First, different professions have different requirements regarding the human capital of employees, resulting differences in labor factor returns among occupations. Second, the fragmentation of the labor market leads to barriers to workers’ mobility in different occupations, resulting in income differentials.

- Industry variable (year): Different industries will affect the labor income of employees; thus, different industries are divided into control variables. A total of 20 industries are divided in this paper according to the national industry standard. The classification of occupations and industries used in this paper is based on Chinese standards. As this paper studies the problem of migrant workers in China, it is appropriate to use Chinese standards for related occupations and industries.

- Characteristic variable of unit ownership: The ownership characteristics of the employment sector will affect the labor income of employees; thus, different ownership characteristics are divided as control variables.

- Region variable (region): A big gap exists in the economic development levels in different regions of China. Therefore, the income gap between different regions is significant. The regional dummy variable was introduced to control this influence. If all the 31 provincial administrative regions in Mainland China are included in the model as dummy variables, then a large degree of freedom will be lost. In fact, in previous studies, the majority of scholars divided China into 3–4 regions to control this influence. Generally speaking, China is divided into eastern, central, western, and northeastern regions according to economic development.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

5. Model Setting and Research Methods

5.1. Salary Regression Equation Setting

5.2. Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition Method

5.3. Quantile Decomposition

6. Analysis of Empirical Results

6.1. Mean Regressive Analysis of Wage Equation and Oaxaca–Blinder Decomposition Results

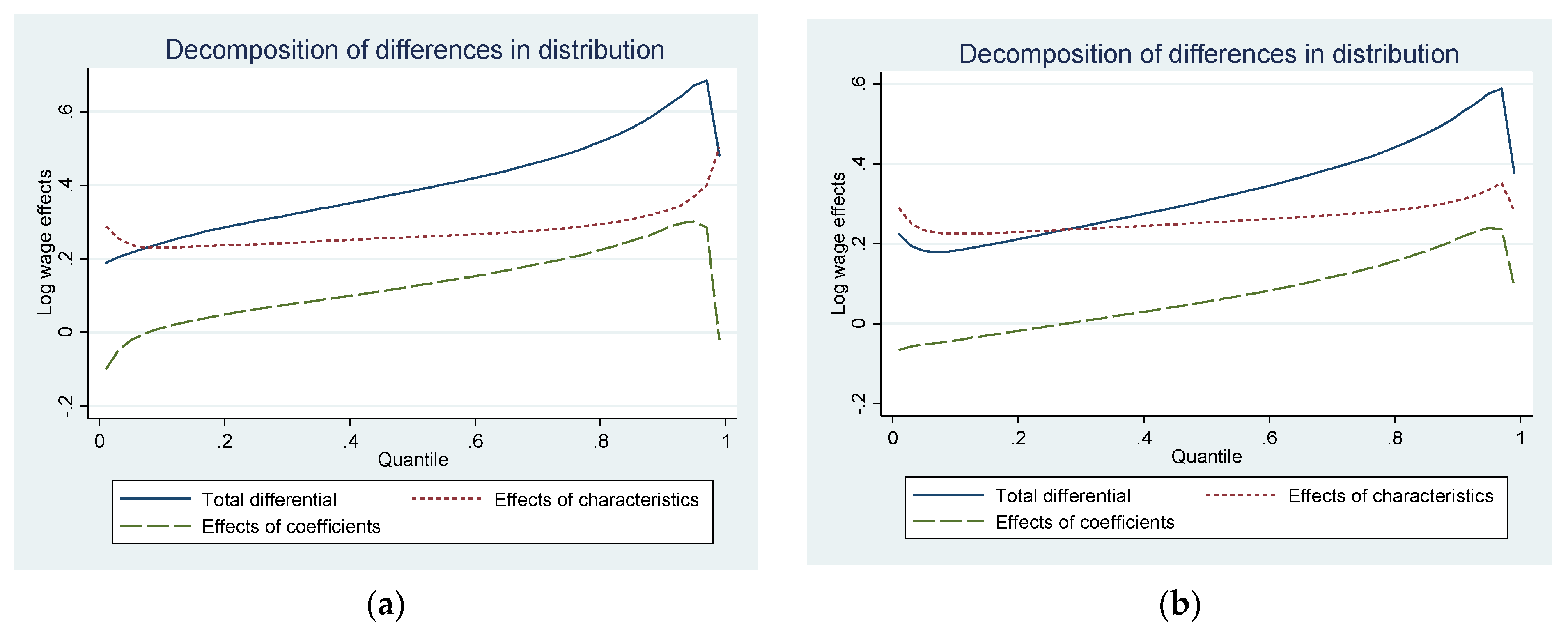

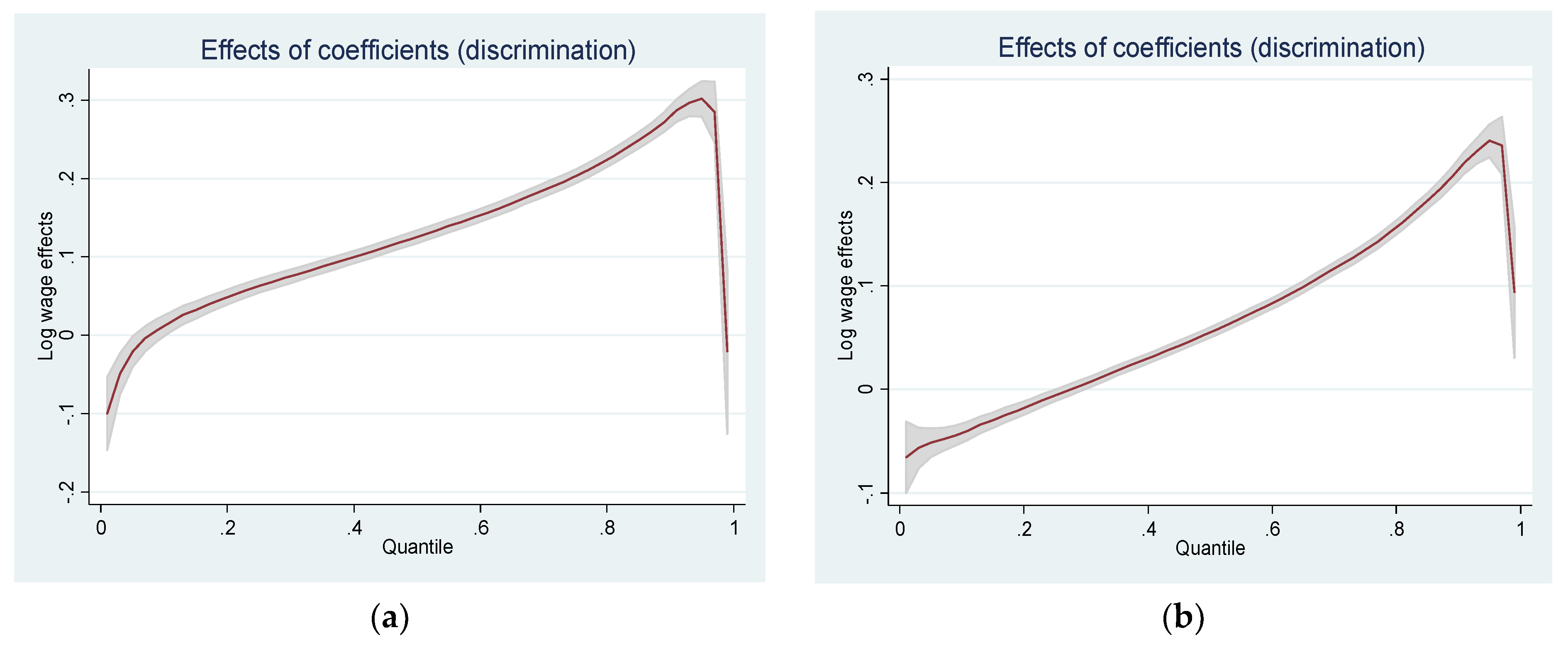

6.2. Analysis of the Results of Quantile Regression and Quantile Decomposition

6.3. Result Analysis of Quantile Regression and Quantile Decomposition of Wage Equation

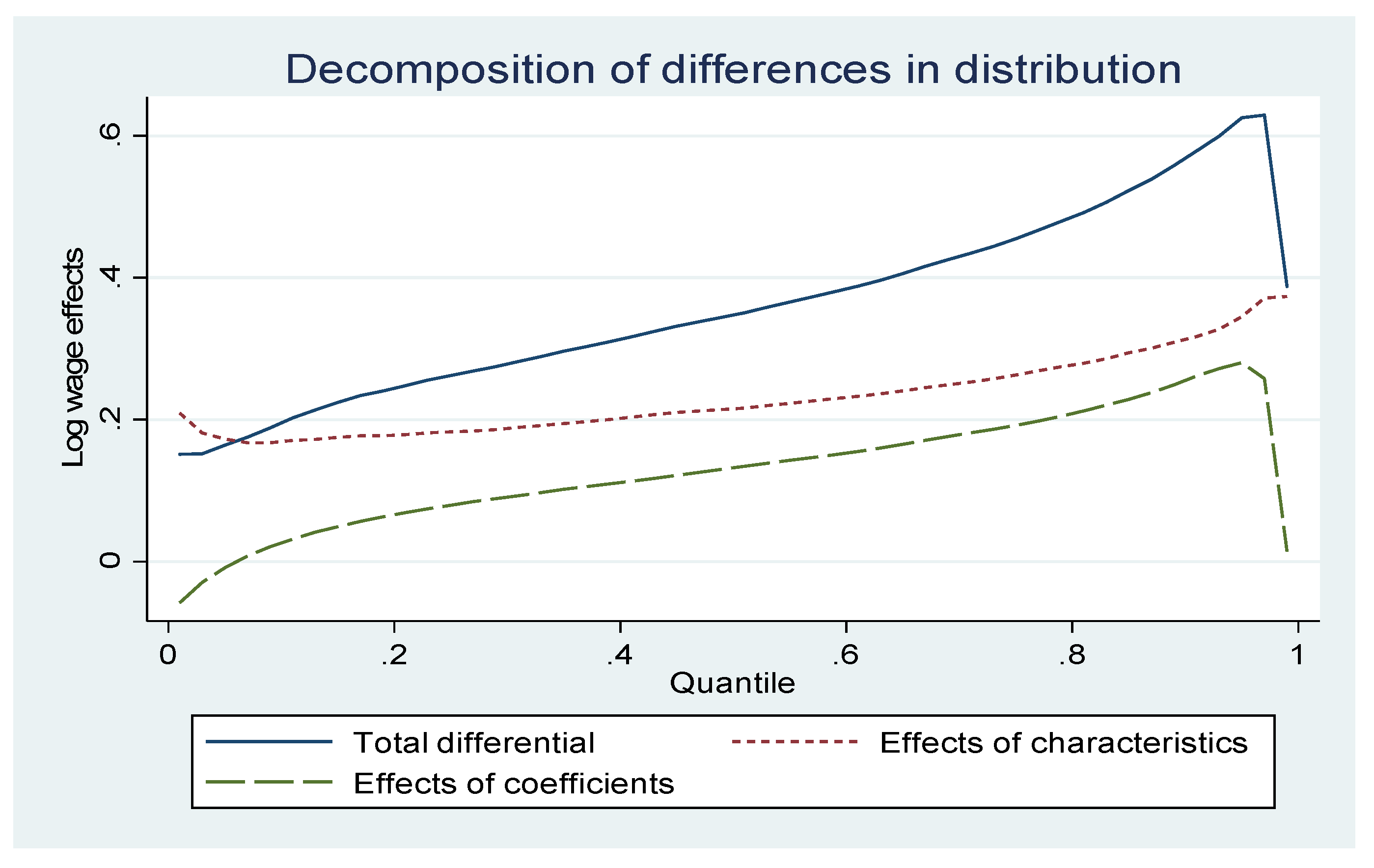

6.4. Robustness Test

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Theoretical Conclusions

7.2. Practical Conclusions

7.3. Limitations and Future Research Line

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morikawa, M. A comparison of the wage structure between the public and private sectors in Japan. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 2016, 39, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X. The research of yield on human capital of rural migrant workers. Youth Stud. 2009, 4, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. Wage difference in the transition period: A quantitative analysis of discrimination. Quant. Econ. 2003, 28, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B. Research on wage difference between urban and rural laborers: Based on the theory of compensatory wage difference. East China Econ. Manag. 2016, 10, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Y. Quantile regression analysis of the difference of salary differences among urban migrants. World Econ. Pap. 2010, 4, 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. Analysis of the citizenization of migrant workers’ salary and its influencing factors from the intergenerational perspective. Econ. Issues 2018, 3, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Deutschmann, C. Labour market segmentation and wage dynamics. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2015, 2, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démurger, S.; Hou, Y.; Yang, W. Forest management policies and resource balance in china: An assessment of the current situation. J. Environ. Dev. 2007, 18, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mincer, J. Human capital and the labor market: A review of current research. Educ. Res. 1989, 18 4, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démurger, S.; Xu, H. Return migrants: The rise of new entrepreneurs in rural China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Peng, J. Urban differences in educational return rate. Chin. Popul. Sci. 2010, 20, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Yao, X. Econometric analysis of migrant workers’ salary discrimination. Chin. Rural Econ. 2006, 26, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Q. Income differences between urban residents and floating population: Decomposition based on method. Chin. Popul. Sci. 2007, 2, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Chen, X. Empirical research on the effect of the household registration system evolvement on labor market segmentation in China: From dual perspectives of employment opportunities and wage gap. Econ. Res. 2012, 12, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, Y.; Zeng, X. The influence of market discrimination on the gender wage gap in urban areas. Econ. Res. 2011, 18, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, C. The income gap between migrant workers and urban workers. Manag. World 2008, 6, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, S. The influence of education and household registration discrimination on the difference of salary between urban workers and migrant workers. Agric. Econ. Issues 2011, 26, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, L.; Liu, L. Discrimination against rural-to-urban migrants: The role of the Hukou System in China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Meng, F.; Wan, H.; Wu, S. Ownership division, household registration discrimination and intergenerational urban-rural wage differences. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2019, 6, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R. Wage differentials between urban residents and rural migrants in urban China during 2002–2007: A distributional analysis. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 37, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yao, Y. A study of the paradox of simultaneous expansion of labor force shift and wage gap: From the perspective of market segmentation. Contemp. Financ. Econ. 2012, 4, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, N.; Yokota, K. Lewis growth model and china’s industrialization. Asian Econ. J. 2008, 22, 359–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, N.; Kong, H.; Yi, S. Research on the Differences in Household Registration Wages from the Perspective of Intergenerational. Stat. Decis. 2020, 1, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.Y.C. Segregated and not equal? Occupation, earnings gap between urban residents and rural migrants in Vietnam. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, B.D.; Tran, G.L.; Nguyen, T.P.T. Social Protection for Rural-Urban Migrants in Vietnam: Current Situation, Challenges, and Opportunities; CSP Research Report No. 8; Institute for Social Development Studies: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.W. The household registration system and migrant labor in China:notes on a dabate. Publ. Dev. Rev. 2010, 36, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Chen, Q.Y.; Wang, R.Y. Household registration reform, labour mobility and optimization of the urban hierarchy. Soc. Sci. 2015, 36, 131–151. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini, I.; Siu, K.; Chan, A. The “rights awakening” of Chinese migrant workers: Beyond the generational perspective. Crit. Asian Stud. 2016, 48, 422–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W. The global financial crisis and migrant workers in china: ‘there is no future as a laborer; returning to the village has no meaning’. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.K. Community-based organizations for migrant workers’ rights: The emergence of labour NGOs in China. Commun. Dev. J. 2013, 48, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Yao, X. Research on the intergenerational differences between migrant workers—Based on wage determination and willingness of staying in the city. Res. Econ. Manag. 2014, 9, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.D.; Meng, X.; Wang, D.W. The Dynamic Change in Wage Gap between Urban Residents and Rural Migrants in Chinese Cities. 2010. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1706289 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Jin, S.F.; Wu, Y.T.; Cheng, M.D. An empirical analysis of the wage difference of the new generation of migrant workers: Based on the survey data of Chengdu. Rural Econ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 29, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M. The consumption level and consumption structure of the new generation of migrant workers: A comparison with the previous generation of migrant workers. J. Labor Econ. 2017, 5, 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, G.; Andersson, R.; Musterd, S.; Kauppinen, T.M. Does neighborhood income mix affect earnings of adults? new evidence from sweden. J. Urban Econ. 2008, 63, 858–870. [Google Scholar]

- Melly, B. Decomposition of differences in distribution using quantile regression. Labour Econ. 2005, 12, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oaxaca, R. Male–female differentials in urban labor markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 1973, 14, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J.A.F.; Mata, J. Counterfactual decomposition of changes in wage distributions using quantile regression. J. Appl. Econom. 2010, 20, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Melly, B. Estimation of Counterfactual Distributions Using Quantile Regression. Ph.D. Thesis, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, D. Towards a Broader Explanation of Male-Female Wage Differences. Cent. Econ. Res. 1999, 99, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atal, J.P.; Nopo, H.; Winder, N. New Century, Old Disparities: Gender and Ethnic Wage Gaps in Latin America; IDB Working Paper IDB-WP-109; Department of Research and Chief Economist, Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Urban Employees | Old Generation of Migrant Workers | New Generation of Migrant Workers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. | S.D. | V. | S.D. | V. | S.D. | |

| Average hourly wage | 29.59 | 33.80 | 18.66 | 24.53 | 19.84 | 25.68 |

| Average years of education (years) | 13.65 | 2.89 | 8.64 | 2.62 | 11.06 | 2.76 |

| Average working experience (years) | 13.35 | 9.55 | 28.65 | 6.37 | 9.52 | 5.58 |

| Degree of education | Amount | % | Amount | % | Amount | % |

| Graduate | 540 | 3.66 | 7 | 0.03 | 104 | 0.25 |

| Undergraduate | 4272 | 28.95 | 148 | 0.70 | 2632 | 6.44 |

| College | 3956 | 26.81 | 514 | 2.44 | 5911 | 14.47 |

| High school and technical Secondary school | 3499 | 23.71 | 3012 | 14.30 | 11,815 | 28.93 |

| Junior middle school | 2233 | 15.13 | 11,630 | 55.22 | 18,488 | 45.27 |

| Primary school or below | 256 | 1.73 | 5752 | 27.31 | 1889 | 4.63 |

| Group by experience | Amount | % | Amount | % | Amount | % |

| 0 to 10 years | 7131 | 48.33 | 0 | 0.00 | 23,583 | 57.75 |

| 11 to 20 years | 4350 | 29.48 | 1431 | 6.79 | 16,694 | 40.88 |

| 21 to 30 years | 2258 | 15.30 | 1,2018 | 57.06 | 562 | 1.38 |

| 31 years and above | 1017 | 6.89 | 7614 | 36.15 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Sample size | 14,694 | 20,997 | 40,772 | |||

| Urban Employees | Old Generation of Migrant Workers | New Generation of Migrant Workers | All Samples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education years (years) | 0.066 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.054 *** | 0.047 *** |

| (25.75) | (9.29) | (38.95) | (46.04) | |

| Work experience (years) | 0.022 *** | −0.024 *** | 0.038 *** | 0.019 *** |

| (10.78) | (−4.87) | (19.33) | (21.99) | |

| The square of years of work experience | −0.001 *** | 0.000 ** | −0.001 *** | −0.000 *** |

| (−9.67) | (2.57) | (−13.01) | (−22.33) | |

| (The old generation is taken as the benchmark.) | ||||

| New generation of migrant workers | 0.027 *** | |||

| (3.54) | ||||

| Urban employees | 0.126 *** | |||

| (16.22) | ||||

| Gender (M = 1) | 0.171 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.183 *** |

| (16.51) | (27.73) | (28.27) | (42.1) | |

| Spouse | 0.090 *** | 0.01 | 0.067 *** | 0.093 *** |

| (6.91) | (0.58) | (9.19) | (15.93) | |

| Occupation | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Industry | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Nature of unit ownership | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Region | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Constant term | 1.937 *** | 3.357 *** | 1.999 *** | 2.177 *** |

| (28.81) | (35.12) | (43.85) | (71.63) | |

| R2 | 0.317 | 0.16 | 0.193 | 0.241 |

| N | 14,694 | 20,997 | 40,722 | 76,413 |

| Total Variances | Characteristic Variances | Coefficient Variances | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | |

| Education years | −0.9870 | 248.61 | −0.2660 *** (−32.97) | 90.27 | −0.7210 *** (−19.17) | 723.17 |

| Work experience | −0.3750 | 94.46 | −0.0520 *** (−6.42) | 17.45 | −0.3230 *** (−13.62) | 323.97 |

| Gender (M = 1) | 0.0788 | −19.85% | 0.0195 *** (14.13) | −6.54 | 0.0593 *** (7.68) | −59.48 |

| Marriage | −0.0951 | 23.95 | 0.0239 *** (12.64) | −8.02 | −0.1190 *** (−6.59) | 119.36 |

| Occupation | −0.0076 | 1.91 | −0.0476 *** (−15.63) | 15.97 | 0.0400 (1.48) | −40.12 |

| Industry | −0.0369 | 9.29 | 0.0167 *** (10.43) | −5.60 | −0.0536 *** (−4.45) | 53.76 |

| Nature of unit ownership | 0.0924 | 23.28 | −0.000856 ** (−2.44) | −2.87 | −0.1010 *** (−4.42) | 101.30 |

| Region | 0.2217 | −55.85 | 0.00871 *** (8.22) | −2.92 | 0.2130 *** (18.17) | −213.64 |

| Constant term | 0.9060 | −228.21 | 0.9060 *** (11.9) | −908.73 | ||

| Total variances | −0.397 *** (−55.97) | 100.00 | −0.298 *** (−38.77) | 100.00 | 0.0997 *** (−10.24) | 100.00 |

| Total Variances | Characteristic Variances | Coefficient Variances | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | % | Value | % | Value | % | |

| Education years | −0.4510 | 137.08 | −0.1720 *** (−48.16) | 74.78 | −0.2790 *** (−7.36) | 282.96 |

| Work experience | 0.1092 | −33.19 | −0.0228 *** (−11.06) | 9.91 | 0.1320 *** (11.19) | −133.87 |

| Gender (M = 1) | −0.0010 | 0.29 | −0.0046 *** (−4.63) | 1.99 | 0.0036 (0.56) | −3.68 |

| Marriage | −0.0464 | 14.10 | −0.0197 *** (−19.29) | 8.57 | −0.0267 ** (−2.57) | 27.08 |

| Occupation | 0.0507 | −15.41 | −0.0241 *** (−15.15) | 10.48 | 0.0748 *** (3.82) | −75.86 |

| Industry | 0.0082 | −2.49 | 0.0070 *** (7.84) | −3.05 | 0.0012 (0.1) | −1.18 |

| Nature of unit ownership | −0.2119 | 64.39 | −0.0099 *** (−10.17) | 4.28 | −0.2020 *** (−9.22) | 204.87 |

| Region | 0.1695 | −51.52 | 0.0155 *** (15.12) | −6.74 | 0.1540 *** (14.68) | −156.19 |

| Constant term | 0.0425 | −12.92 | 0.0425 (0.67) | −43.10 | ||

| Total variances | 0.329 *** (−50.41) | 100.00 | −0.23 *** (−47.46) | 100.00 | −0.0986 *** (−13.99) | 100.00 |

| OLS | QR_10 | QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | QR_90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of education | 0.066 *** | 0.071 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.063 *** |

| (28.35) | (14.53) | (21.07) | (36.41) | (20.68) | (11.04) | |

| Work experience | 0.022 *** | 0.028 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.021 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.027 *** |

| (11.49) | (8.26) | (5.52) | (9.23) | (10.92) | (8.02) | |

| Square of work experience | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (−10.53) | (−7.80) | (−5.51) | (−9.00) | (−9.97) | (−7.56) | |

| Gender (M = 1) | 0.171 *** | 0.131 *** | 0.145 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.193 *** | 0.224 *** |

| (16.54) | (10.19) | (14.3) | (14.2) | (18.64) | (12.02) | |

| Marriage | 0.090 *** | 0.058 ** | 0.064 ** | 0.066 *** | 0.085 *** | 0.120 *** |

| (6.92) | (2.68) | (3.1) | (4.97) | (6.71) | (5.84) | |

| Occupation | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Industry | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Nature of unit ownership | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Region | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Constant term | 1.937 *** | 1.088 *** | 1.584 *** | 1.897 *** | 2.270 *** | 2.599 *** |

| (31.64) | (8.55) | (19.77) | (30.63) | (29.18) | (17.22) | |

| R2 | 0.317 | 0.1522 | 0.1752 | 0.2042 | 0.2166 | 0.2086 |

| N | 14,694 | 14,694 | 14,694 | 14,694 | 14,694 | 14,694 |

| OLS | QR_10 | QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | QR_90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of education | 0.0183 *** | 0.0145 *** | 0.0176 *** | 0.0192 *** | 0.0220 *** | 0.0193 *** |

| (9.84) | (4.74) | (8.35) | (9.67) | (9.11) | (8.38) | |

| Work experience | −0.0237 *** | −0.0208 *** | −0.0117 * | −0.0177 *** | −0.0321 *** | −0.0424 *** |

| (−5.41) | (−3.86) | (−2.02) | (−4.09) | (−4.89) | (−4.69) | |

| Square of work experience | 0.000 ** | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** |

| (2.91) | (1.57) | (0.09) | (1.54) | (3.37) | (3.59) | |

| Gender (M = 1) | 0.234 *** | 0.224 *** | 0.220 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.250 *** | 0.233 *** |

| (27.41) | (15.39) | (20.21) | (28.81) | (28.68) | (14.91) | |

| Marriage | 0.00958 | 0.0328 | 0.0336 | 0.0116 | 0.0112 | −0.0142 |

| (0.64) | (1.09) | (1.73) | (1.04) | (0.69) | (−0.49) | |

| Occupation | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Industry | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Nature of unit ownership | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Region | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Constant term | 1.937 *** | 1.088 *** | 1.584 *** | 1.897 *** | 2.270 *** | 2.599 *** |

| (31.64) | (8.55) | (19.77) | (30.63) | (29.18) | (17.22) | |

| R2 | 0.160 | 0.099 | 0.107 | 0.1137 | 0.1048 | 0.1003 |

| N | 20,997 | 20,997 | 20,997 | 20,997 | 20,997 | 20,997 |

| OLS | QR_10 | QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | QR_90 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of education | 0.054 *** | 0.0568 *** | 0.0533 *** | 0.0530 *** | 0.0528 *** | 0.0564 *** |

| (40.88) | (27.76) | (33.27) | (49.79) | (37.47) | (30.66) | |

| Work experience | 0.0379 *** | 0.0409 *** | 0.0363 *** | 0.0330 *** | 0.0321 *** | 0.0351 *** |

| (19.97) | (8.79) | (18.17) | (18.09) | (12.57) | (18.14) | |

| Square of work experience | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** | −0.001 *** |

| (−13.45) | (−6.78) | (−10.84) | (−11.95) | (−7.61) | (−10.95) | |

| Gender (M = 1) | 0.164 *** | 0.135 *** | 0.149 *** | 0.176 *** | 0.184 *** | 0.201 *** |

| (28.32) | (14.92) | (24.55) | (37.88) | (32.98) | (21.6) | |

| Marriage | 0.0666 *** | 0.0815 *** | 0.0566 *** | 0.0565 *** | 0.0710 *** | 0.0920 *** |

| (9.36) | (10.87) | (8.19) | (13.51) | (15.07) | (7.84) | |

| Occupation | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Industry | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Nature of unit ownership | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Region | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Constant term | 1.999 *** | 1.107 *** | 1.744 *** | 2.070 *** | 2.337 *** | 2.624 *** |

| (49.83) | (12.52) | (25.62) | (64.45) | (39.43) | (37.5) | |

| R2 | 0.1926 | 0.1053 | 0.1163 | 0.1272 | 0.1337 | 0.1282 |

| N | 40,722 | 40,722 | 40,722 | 40,722 | 40,722 | 40,722 |

| Quantile | Total Variances | Characteristic Variances | Coefficient Variances | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.V. | Ratio (%) | D.V. | Ratio (%) | ||

| 0.1 | 0.24309 | 0.23026 | 94.72% | 0.01284 | 5.28% |

| 0.2 | 0.28496 | 0.23662 | 83.04% | 0.04833 | 16.96% |

| 0.3 | 0.31788 | 0.2428 | 76.38% | 0.07509 | 23.62% |

| 0.4 | 0.35134 | 0.25165 | 71.62% | 0.09969 | 28.38% |

| 0.5 | 0.38448 | 0.25913 | 67.40% | 0.12536 | 32.60% |

| 0.6 | 0.41923 | 0.26634 | 63.53% | 0.15288 | 36.47% |

| 0.7 | 0.46215 | 0.2769 | 59.91% | 0.18526 | 40.09% |

| 0.8 | 0.51763 | 0.29393 | 56.78% | 0.2237 | 43.22% |

| 0.9 | 0.60692 | 0.32776 | 54.00% | 0.27916 | 46.00% |

| 0.99 | 0.48172 | 0.502211 | 104.25% | −0.020491 | −4.25% |

| Quantile | Total Variances | Characteristic Variances | Coefficient Variances | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.V. | Ratio (%) | D.V. | Ratio (%) | ||

| 0.1 | 0.18384 | 0.22538 | 122.60% | −0.04155 | −22.60% |

| 0.2 | 0.21122 | 0.22944 | 108.63% | −0.01823 | −8.63% |

| 0.3 | 0.24282 | 0.23709 | 97.64% | 0.00573 | 2.36% |

| 0.4 | 0.27528 | 0.24496 | 88.99% | 0.03032 | 11.01% |

| 0.5 | 0.30850 | 0.25340 | 82.14% | 0.05511 | 17.86% |

| 0.6 | 0.34534 | 0.26201 | 75.87% | 0.08332 | 24.13% |

| 0.7 | 0.38865 | 0.27192 | 69.97% | 0.11673 | 30.03% |

| 0.8 | 0.44117 | 0.28430 | 64.44% | 0.15687 | 35.56% |

| 0.9 | 0.52099 | 0.30804 | 59.13% | 0.21295 | 40.87% |

| Quantile | Total Variances | Characteristic Variances | Coefficient Variances | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.V. | Ratio (%) | D.V. | Ratio (%) | ||

| 0.1 | 0.19562 | 0.16810 | 85.93 | 0.02753 | 14.07 |

| 0.2 | 0.24414 | 0.17820 | 72.99 | 0.06595 | 27.01 |

| 0.3 | 0.27826 | 0.18756 | 67.40 | 0.09071 | 32.60 |

| 0.4 | 0.31350 | 0.20189 | 64.40 | 0.11162 | 35.60 |

| 0.5 | 0.34745 | 0.21537 | 61.99 | 0.13208 | 38.01 |

| 0.6 | 0.38423 | 0.23134 | 60.21 | 0.15289 | 39.79 |

| 0.7 | 0.43003 | 0.25112 | 58.40 | 0.17891 | 41.60 |

| 0.8 | 0.48561 | 0.27708 | 57.06 | 0.20853 | 42.94 |

| 0.9 | 0.56847 | 0.31308 | 55.07 | 0.25539 | 44.93 |

| Quantile | Total Variances | Characteristic Variances | Coefficient Variances | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.V. | Ratio (%) | D.V. | Ratio (%) | ||

| 0.1 | 0.09246 | 0.12111 | 130.99 | −0.02865 | −30.99 |

| 0.2 | 0.12734 | 0.13136 | 103.16 | −0.00402 | −3.16 |

| 0.3 | 0.16036 | 0.14101 | 87.93 | 0.01935 | 12.07 |

| 0.4 | 0.19230 | 0.14976 | 77.88 | 0.04255 | 22.12 |

| 0.5 | 0.22498 | 0.15899 | 70.67 | 0.06599 | 29.33 |

| 0.6 | 0.26147 | 0.17041 | 65.17 | 0.09106 | 34.83 |

| 0.7 | 0.30275 | 0.18205 | 60.13 | 0.12070 | 39.87 |

| 0.8 | 0.35244 | 0.19794 | 56.16 | 0.15450 | 43.84 |

| 0.9 | 0.42399 | 0.22284 | 52.56 | 0.20115 | 47.44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Pérez-Sánchez, M.d.l.Á.; Yi, S.; Parra-Lopez, E.; Bu, N. Establishing a Sustainable Labor Market in Developing Countries: A Perspective of Generational Differences in Household Wage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111835

Li D, Pérez-Sánchez MdlÁ, Yi S, Parra-Lopez E, Bu N. Establishing a Sustainable Labor Market in Developing Countries: A Perspective of Generational Differences in Household Wage. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111835

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ding, María de los Ángeles Pérez-Sánchez, Shun Yi, Eduardo Parra-Lopez, and Naipeng (Tom) Bu. 2021. "Establishing a Sustainable Labor Market in Developing Countries: A Perspective of Generational Differences in Household Wage" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111835