Speech and Language Therapy Service for Multilingual Children: Attitudes and Approaches across Four European Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)

1.2. Multilingualism

1.3. Speech and Language Therapy in Multilingual Contexts

1.3.1. Lack of Language Proficiency beyond the Societal Language

1.3.2. Lack of Satisfactory Diagnostic Tools Available for the Multilingual Population

1.3.3. SLTs’ Preparedness and Confidence Assessing and Treating Multilingual Children

1.4. Country-Specific Differences

1.4.1. Education and SLT Training

1.4.2. Referral Policy

1.4.3. Therapy Costs and Insurance Coverage

1.4.4. Immigration Census Data and History

1.5. Research Goals and Hypotheses

- •

- to explore SLTs’ beliefs and approaches towards treating multilingual children both within and comparing the four countries through an online questionnaire;

- •

- to assess how variables that were explicitly addressed in the questionnaire and that could differ both within and across countries affect attitudes and approaches in SLT services for multilingual children, precisely:

- •

- SLTs’ overall professional experience (measured in years),

- •

- Experience in specifically working with multilingual children,

- •

- Educational background (BA vs. MA), indicated by respondents’ years of education,

- (This variable was taken into consideration for the Italian sample only since the educational/training system for SLT in Italy is more homogeneous on a national level (3 years of BA compulsory; 2 additional years of MA optional).)

- •

- Respondents’ personal language background (being monolingual vs. multilingual),

- (This variable was only taken into account for the subgroup of German-speaking SLTs (working in Germany, Austria, or Switzerland) to investigate how SLTs’ beliefs regarding multilingualism influence their approaches in terms of applied procedures in the clinical practice. Since these countries compared to Italy have a larger proportion of multilingual citizens, due to both historical (migration) and educational factors (only about 14% of the overall population speaks English versus 40% in Austria and 31% in Germany, with only four additional language groups exceeding 1%, not including any language from migrant contexts, versus eight additional languages in Austria and seven in Germany, including various minority languages from migration contexts) [62]).

- The large majority of SLTs acknowledge the importance of taking into account aspects of the child’s heritage language and culture when treating multilingual children and providing parent training.

- The large majority of SLTs is aware of, and—presuming that existing tools are reasonably applicable and easily accessible—optimally makes use of, a series of tools that facilitate SLT service provision for multilingual children (i.e., multilingual and computerized solutions).

- Differences among the countries reflect the organizational, sociological, and historical differences described above but are mediated by SLTs’ experience level in working with multilingual children.

- SLTs’ experience in working with multilingual children positively correlates with greater awareness of the need for multilingual approaches and with better knowledge of available tools specifically designed for multilingual children.

- A longer duration of overall SLT practice (professional experience in years) is linked with more multilingually oriented approaches in SLT service provision.

- A longer duration of SLT education/training is linked with more multilingually oriented approaches in SLT service provision.

- Multilingual SLTs attribute more importance to multilingual approaches in SLT service for multilingual children, due to their greater awareness (and personal experience) of cross-linguistic influence and facilitation processes occurring across languages.

- Knowledge of special diagnostic material is associated with its actual use while providing SLT services for multilingual children.

- SLTs’ who declare that DLD is not likely to be exacerbated by multilingualism (i.e., second language acquisition or cross-linguistic influence) are more open to a linguistically diverse language environment.

- SLTs who favor the use of heritage language at home would be more likely to adopt multilingual approaches and are more open to multilingual material (including information and communications technology (ICT) solutions) in SLT services.

- SLTs who have more experience and/or more extensive education and/or attribute more relevance to the multilingual background of their patients would also be more aware of the potential impact that multilingualism may have on both therapy and parent consultation.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Questionnaire Design

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Declaration of Consent and Data Storage

3. Results

3.1. SLTs’ Characteristics

3.2. SLTs’ Attitudes in the Whole Sample

3.3. SLTs’ Clinical Approaches in the Whole Sample

3.4. Country-Related Effects

3.5. Effects of Duration of SLTs’ Education and Language Background

3.6. Effects of SLTs’ Attitudes towards Children’s Heritage Language

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Experience and Education

4.2. Country-Related Differences: Historical, Social, and Health Policy-Related Factors

4.3. SLTs’ Language Background

4.4. Discrepancies between Knowledge and Practice

4.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

4.6. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question Number | Question | Answering Options |

|---|---|---|

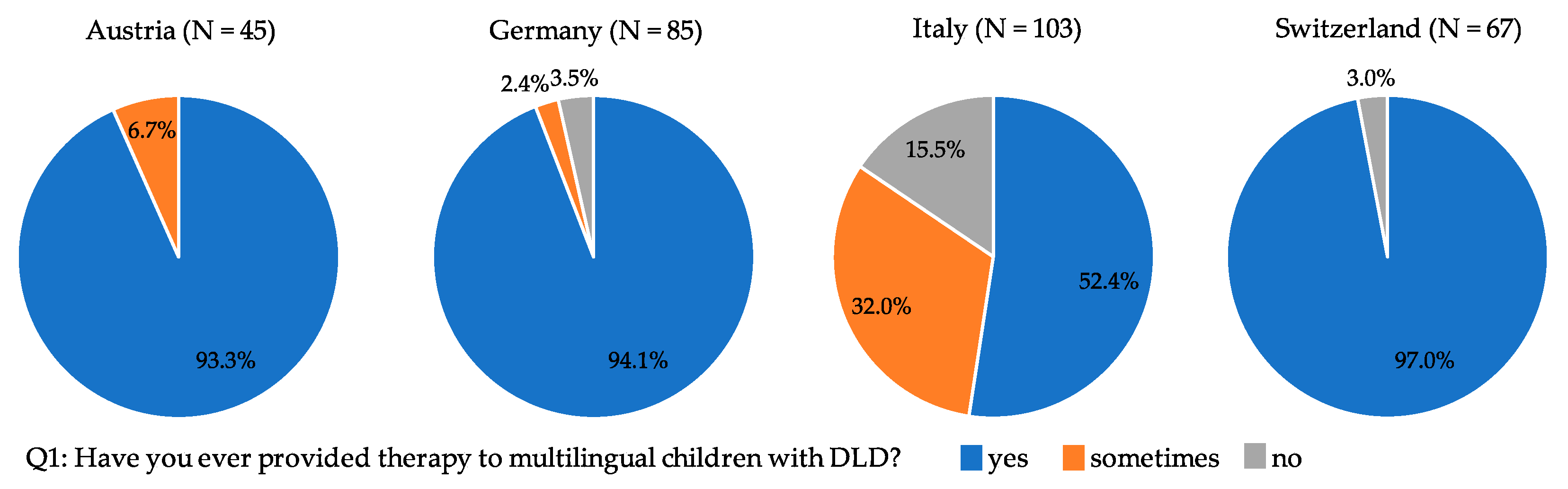

| Q1 | Have you ever provided therapy to multilingual children with developmental language disorder (DLD)? | Yes Sometimes never |

| Q2 | Do you think that different approaches are needed in the diagnosis and treatment of multilingual children compared to monolingual children? | Yes Sometimes never |

| Q3 | Do you think that (A) the therapy of DLD of multilingual children should be limited exclusively to the societal language, or that (B) the child’s first language should also be taken into account? | A more A than B more B than A B |

| Q4 | Do you believe that (A) DLD is independent of speaking a second language, or that (B) multilingualism can impact the manifestation of DLD? 2 | A more A than B more B than A B |

| Q5 | Do you think that (A) it would be better for multilingual children with DLD to speak only one language (both at home and outside of the family environment), or that (B) it would be better for all of a child’s communication partners to interact with the child in the language they know best? | A B |

| Q6 | In the context of speech and language therapy (SLT) for multilingual children with DLD, do you think that it is useful to compare a child’s language performance in his/her first and second language? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q7 | If yes/sometimes/rarely (Q6)…(A) were your comparisons based on information provided by the parents or (B) were you able to directly observe child behavior in both languages (possibly in the presence of parents)? | A more A than B more B than A B |

| Q8 | Are you aware of any testing or other diagnostic material that have been developed specifically for multilingual children with DLD? | Yes no |

| Q9 | Do you use special diagnostic material/tools for multilingual children with DLD? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q10 | If yes/sometimes/rarely (Q9)… What diagnostic material/tools do you use for multilingual children with DLD? | [open question, free text answer] |

| Q11 | Do you think it would be useful to check whether the phonemes that cause difficulties to the child in the societal language are present 3/also affected 4 in the heritage language? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q12 | Do you think it would be useful to check whether the syntactic and morphological structures that cause difficulties to the child the societal language are present 5/also affected 6 in the heritage language? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q13 | Do you think it would be useful to check whether words that the child uses semantically/lexically incorrectly in the societal language are similar or very different in the heritage language? | Yes Sometimes rarely never |

| Q14 | Do you think it would be useful to check whether words that the child uses semantically/lexically incorrectly in German (i.e., the societal language) are also used incorrectly in the heritage language? 7 | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q15 | Do you think it would be useful to have a summary chart of the phoneme inventory of the child’s heritage language? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q16 | Do you think it would be useful to have a summary table of the main syntactic structures and constructions in the child’s heritage language? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q17 | Do you think that an overview table with a list of the most important prepositions (translation + usage) in the child’s heritage language would be useful? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q18 | Do you think that computerized tasks to assess the level of proficiency in the child’s other language would be useful? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q19 | If such tasks existed, would you use them when working with multilingual children with DLD? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q20 | Do you think it would be useful to give the child and his/her family tasks to take home to practice in heritage language? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q21 | If such tasks were available to you, would you use them? | Yes Sometime rarely never |

| Q22 | Do you think that differences in the languages spoken by the child and the therapist may influence the quality of the intervention? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q23 | Do you think that differences in the languages spoken may the quality of the parent consultation? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q24 | Do you think that cultural differences between the SLT and the child’s family influence the quality of parent consultation? | Yes Sometimes Rarely never |

| Q25 | For how many years have you practiced/have you been practicing Speech and Language Therapy? | <5 years 5–10 years 10–20 years >20 years |

| Q26 | What percentages of children you diagnose/treat for DLD are multilingual? | 0–5% 6–2% 26–50% 51–75% 76–95% 96–100% |

| Q27 | Besides German, do you speak any other language(s) at native level? 8 | Yes no |

| Q28 | If yes (Q27), what language(s) do you speak any other language(s) at native level? 9 | [open question, free text answer] |

| Q 29 | What is your educational qualification? 10 | BA in SLT (3 years) MA in SLT (5 years) other |

References

- Johnson, C.J.; Beitchman, J.H.; Brownlie, E.B. Twenty-Year Follow-Up of Children with and Without Speech-Language Impairments: Family, Educational, Occupational, and Quality of Life Outcomes. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2010, 19, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snowling, M.J.; Bishop, D.; Stothard, S.E.; Chipchase, B.; Kaplan, C. Psychosocial outcomes at 15 years of children with a preschool history of speech-language impairment. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 759–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. THE 17 GOALS|Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D.V.; Snowling, M.J.; Thompson, P.A.; Greenhalgh, T. Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, L.B. Children with Specific Language Impairment; MIT Press paperback ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sansavini, A.; Favilla, M.E.; Guasti, M.T.; Marini, A.; Millepiedi, S.; Di Martino, M.V.; Vecchi, S.; Battajon, N.; Bertolo, L.; Capirci, O.; et al. Developmental Language Disorder: Early Predictors, Age for the Diagnosis, and Diagnostic Tools. A Scoping Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrhenius, B.; Gyllenberg, D.; Chudal, R.; Lehti, V.; Sucksdorff, M.; Sourander, O.; Virtanen, J.-P.; Torsti, J.; Sourander, A. Social risk factors for speech, scholastic and coordination disorders: A nationwide register-based study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boivin, M.J.; Kakooza, A.M.; Warf, B.C.; Davidson, L.L.; Grigorenko, E.L. Reducing neurodevelopmental disorders and disability through research and interventions. Nature 2015, 527, S155–S160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grosjean, F. Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism; Harvard Univ. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Caroll, S.E. Exposure and input in bilingual development. Bilingualism 2017, 20, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crescentini, C.; Marini, A.; Fabbro, F. Competence and Language Disorders in Multilinguals. EL.LE Educ. Linguist. Lang. Educ. 2012, 1, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Oller, D.K.; Pearson, B.Z.; Cobo-Lewis, A.B. Profile effects in early bilingual language and literacy. Appl. Psycholinguist. 2007, 28, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garraffa, M.; Vender, M.; Sorace, A.; Guasti, M.T. Is it possible to differentiate multilingual children and children with Developmental Language Disorder? Lang. Soc. Policy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armon-Lotem, S.; de Jong, J. Introduction. In Assessing Multilingual Children: Disentangling Bilingualism from Language Impairment, 1st ed.; Armon-Lotem, S., de Jong, J., Meir, N., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lüke, C.; Ritterfeld, U. Mehrsprachige Kinder in sprachtherapeutischer Behandlung: Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Heilpädagogische Forsch. 2011, 37, 188–197. [Google Scholar]

- Scharff Rethfeldt, W. Logopädische Versorgungssituation mehrsprachiger Kinder mit Sprachentwicklungsstörungen: Das MeKi-SES-Projekt zur Versorgung einer ambulanten Inanspruchnahmepopulation in Bremen. Forum Logopädie 2017, 4, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zmarich, C.; Lena, L.; Pinton, A. Lo sviluppo fonetico fonologico nell’acquisizione di L1 e di L2. In I Disturbi del Linguaggio I Disturbi del Linguaggio: Caratteristiche, Valutazione, Trattamento; Marotta, L., Caselli, M.C., Eds.; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2014; pp. 87–124. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, J.; Crago, M.; Genesee, F.; Rice, M. French-English Bilingual Children With SLI. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2003, 46, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tomblin, J.B.; Records, N.L.; Buckwalter, P.; Zhang, X.; Smith, E.; O’Brien, M. Prevalence of Specific Language Impairment in Kindergarten Children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 1997, 40, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehti, V.; Gyllenberg, D.; Suominen, A.; Sourander, A. Finnish-born children of immigrants are more likely to be diagnosed with developmental disorders related to speech and language, academic skills and coordination. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lamo White, C.; Jin, L. Evaluation of speech and language assessment approaches with bilingual children. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2011, 46, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huer, M.B.; Saenz, T.I. Challenges and Strategies for Conducting Survey and Focus Group Research with Culturally Diverse Groups. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2003, 12, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, N.; Marchman, V.A.; Fernald, A. Does input influence uptake? Links between maternal talk, processing speed and vocabulary size in Spanish-learning children. Dev. Sci. 2008, 11, F31–F39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huttenlocher, J.; Waterfall, H.; Vasilyeva, M.; Vevea, J.; Hedges, L.V. Sources of variability in children’s language growth. Cogn. Psychol. 2010, 61, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, B.; Risley, T.R. Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children; P.H. Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, B.; Risley, T. The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age. Am. Educ. 2003, 27, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, A.; Bialystok, E. Independent effects of bilingualism and socioeconomic status on language ability and executive functioning. Cognition 2014, 130, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scharff Rethfeldt, W. Kultursensible logopädische Versorgung in der Krise-zur Relevanz sozialer Evidenz. Forum Logopädie 2016, 30, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- von Suchodoletz, W.; Macharey, G. Stigmatisierung sprachgestörter Kinder aus Sicht der Eltern. Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2006, 55, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, M.; Scharff Rethfeldt, W.; Grech, H.; Letts, C.; Muller, C.; Salameh, E.-K.; Vandewalle, E. Position Statement on Language Impairment in Multilingual Children. In Proceedings of the 30th World Congress of the International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics (IALP), Dublin, Ireland, 21–25 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scharff Rethfeldt, W.; McNeilly, L.; Abutbul-Oz, H.; Blumenthal, M.; de Goulart, G. Common Questions by SLT-SLP About Bilingual-Multilingual Children and Informed Evidence-Based Answers; IALP: Birkirkara, Malta, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marinova-Todd, S.H.; Colozzo, P.; Mirenda, P.; Stahl, H.; Kay-Raining Bird, E.; Parkington, K.; Cain, K.; de Scherba Valenzuela, J.; Segers, E.; Segers, A.N.M.; et al. Professional practices and opinions about services available to bilingual children with developmental disabilities: An international study. J. Comm. Dis. 2014, 63, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich, S.; von Knebel, U. Sprachtherapie mit sukzessiv mehrsprachigen Kindern mit Sprachentwicklungsstörungen: Eine empirische Analyse gegewärtiger Praxiskonzepte im Bundesland Berlin. Forsch. Sprache 2017, 5, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.J.; McLeod, S. Speech-language pathologists’ assessment and intervention practices with multilingual children. Int. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 2012, 14, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordaan, H. Clinical Intervention for Bilingual Children: An International Survey. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2008, 60, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, M.A.; Morgan, G.P.; Thompson, M.S. The Efficacy of a Vocabulary Intervention for Dual-Language Learners with Language Impairment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013, 56, 748–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordardottir, E.; Cloutier, G.; Ménard, S.; Pelland-Blais, E.; Rvachew, S. Monolingual or bilingual intervention for primary language impairment? A randomized control trial. J. speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2015, 58, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerma, T.; Blom, E. Assessment of bilingual children: What if testing both languages is not possible? J. Commun. Disord. 2017, 66, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, P.; Tracy, R. Linguistische Sprachstandserhebung—Deutsch als Zweitsprache (LiSe-DaZ); Hogrefe: Bern, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gagarina, N. Diagnostik von Erstsprachkompetenzen im Migrationskontext. In Handbuch Spracherwerb und Sprachentwicklungsstörungen: Mehrsprachigkeit, Auflage; Chilla, S., Haberzettl, S., Eds.; Urban & Fischer: München, Germany, 2014; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chilla, S. Grundfragen der Diagnostik im Kontext von Mehrsprachigkeit und Synopse diagnostischer Verfahren. In Handbuch Spracherwerb und Sprachentwicklungsstörungen: Mehrsprachigkeit, Auflage; Chilla, S., Haberzettl, S., Eds.; Urban & Fischer: München, Germany, 2014; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, A.; Schulz, P. Specific Language Impairment and Early Second Language Acquisition: The Risk of Over- and Underdiagnosis. Child. Ind. Res. 2014, 7, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseberry-McKibbin, C.; Brice, A.; O’Hanlon, L. Serving English Language Learners in Public School Settings. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2005, 36, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintruff, Y.; Orlando, A.; Gumpert, M. Diagnostische Praxis bei mehrsprachigen Kindern—Eine Umfrage unter Therapeuten zur Entscheidung über den Therapiebedarf mehrsprachiger Kinder mit sprachlichen Auffälligkeiten. Forum Logopädie 2011, 25, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Grandpierre, V.; Milloy, V.; Sikora, L.; Fitzpatrick, E.; Thomas, R.; Potter, B. Barriers and facilitators to cultural competence in rehabilitation services: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, C.; Kay-Raining Bird, E.; Deacon, H. Survey of Canadian Speech-Language Pathology Service Delivery to Linguistically Diverse Clients. Can. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 2012, 36, 18–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacci, P.; Atti, E.; Casamenti, M.; Piani, B.; Porrelli, M.; Mari, R. Which Measures Better Discriminate Language Minority Bilingual Children with and Without Developmental Language Disorder? A Study Testing a Combined Protocol of First and Second Language Assessment. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2020, 63, 1898–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis, J.; Schneider, P.; Duncan, T.S. Discriminating Children with Language Impairment Among English-Language Learners from Diverse First-Language Backgrounds. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 2013, 56, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triarchi-Herrmann, V. Zur Förderung und Therapie der Sprache bei Mehrsprachigkeit. In Spektrum Patholinguistik; Universitätsverlag Potsdam: Potsdam, Germany, 2009; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Contento, S.; Bellocchi, S.; Bonifacci, P. BaBIL: Prove per la Valutazione delle Competenze Verbali e Non-Verbali in Bambini Bilingui-Manuale e Materiali; Giunti O.S.: Florence, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hautala, J.; Heikkilä, R.; Nieminen, L.; Rantanen, V.; Latvala, J.-M.; Richardson, U. Identification of Reading Difficulties by a Digital Game-Based Assessment Technology. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2020, 58, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, M.A.; Sutherland, R.; Jeng, K.; Bale, G.; Batta, P.; Cambridge, A.; Detheridge, J.; Drevensek, S.; Edwards, L.; Everett, M. Agreement between telehealth and face-to-face assessment of intellectual ability in children with specific learning disorder. J. Telemed. Telecare. 2018, 25, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, G.; Ng, V.; Lim, B.H.; Tan, W.P.; Lukito, N. The computerised-based Lucid Rapid Dyslexia Screening for the identification of children at risk of dyslexia: A Singapore study. Educ. Child. Psychol. 2011, 28, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Motsch, H.-J. ESGRAF-MK: Mit 16 Abbildungen und 17 Tabellen: Mit Diagnostik-Software auf CD-ROM; Ernst Reinhardt Verlag: München, Germany; Basel, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Speakaboo. Available online: http://www.speakaboo.io/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Stankova, M.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, I.R.; Matić, A.; Levickis, P.; Lyons, R.; Messarra, C.; Kouba Hreich, E.; Vulchanova, M.; Vulchanov, V.; Czaplewska, E.; et al. Cultural and Linguistic Practice with Children with Developmental Language Disorder: Findings from an International Practitioner Survey. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Migration and Migrant Population Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Chancellerie Fédérale. Message Relatif à l’initiative Populaire “Contre l’immigration de Masse”. Available online: https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/fga/2013/50/fr (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Bundeskanzleramt. Integrationsbericht 2020. 10 Jahre Expertenrat—10 Jahre Integrationsbericht. Available online: https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/service/publikationen-aus-dem-bundeskanzleramt/publikationen-zu-integration/integrationsberichte.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Fondazione ISMU. Dati Sulle Migrazioni: Immigrati in Italia ed in Europa—Fond. ISMU. Available online: https://www.ismu.org/dati-sulle-migrazioni/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Language Knowledge. The Most Spoken Languages in Europe. Available online: http://languageknowledge.eu/ (accessed on 22 September 2021).

| Country | Foreign-Born Population 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Thousand | % of the Population | |

| Germany | 15,040.7 | 18.1 |

| Italy | 6161.4 | 10.3 |

| Austria | 1760.6 | 19.8 |

| Switzerland | 509.7 | 29.2 |

| Germany | Italy | Austria | Switzerland | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of Citizenship | % | Country of Citizenship | % | Country of Citizenship | % | Country of Citizenship | % |

| Turkey | 12.7 | Romania | 22.7 | Germany | 13.6 | Italy | 18.0 |

| Poland | 7.4 | Albania | 8.4 | Romania | 8.4 | Germany | 7.8 |

| Syria | 7.3 | Morocco | 8.2 | Serbia | 8.3 | Portugal | 7.3 |

| Romania | 6.8 | China | 5.7 | Turkey | 8.0 | France | 5.3 |

| Italy | 5.7 | Ukraine | 4.5 | Bosnia Herzegovina | 6.6 | Spain | 4.2 |

| Other | 60.1 | Other | 50.4 | Other | 55.2 | Other | 57.5 |

| What Percentage of Children you Diagnose/Treat for DLD are Multilingual? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–5% | 6–25% | 26–50% | 51–75% | 76–95% | 96–100% | |

| proportion of German-speaking SLT respondents (n = 154) | 5.8% | 22.1% | 24.7% | 26.6% | 16.2% | 4.6% |

| A | More A Than B | More B Than A | B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q3 Do you think that (A) the therapy of DLD in multilingual children should be limited exclusively to the societal language, or that (B) the child’s heritage language should also be taken into account? | 3.0% | 25.4% | 36.8% | 34.8% |

| Q4 Do you believe that (A) DLD is independent of speaking a second language, or that (B) multilingualism may impact the manifestation of DLD? | 34.7% | 24.3% | 29.3% | 11.7% |

| Do You Think That It Would Be Useful/Helpful to… | No | Rarely | Sometimes | Yes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q6 … compare a child’s language performance in his/her heritage and societal language? | 2.0% | 4.7% | 29.1% | 63.4% |

| Q11 … check whether the phonemes that cause difficulties to the child in the societal language are present/are also affected in the heritage language? | 2.0% | 3.3% | 15.0% | 79.7% |

| Q15 … have a summary chart of the phoneme inventory of the child’s heritage language? | 1.7% | 3.7% | 17.7% | 77.7% |

| Q12 … check whether the syntactic and morphological structures that cause difficulties to the child in the societal language are present/are also affected in the heritage language? | 4.3% | 1.7% | 17.0% | 77.7% |

| Q16 … have a summary table of the main syntactic structures and constructions in the child’s heritage language? | 2.0% | 1.7% | 14.3% | 82.0% |

| Q13 … check whether words that the child uses semantically/lexically incorrectly in the societal language are similar or very different from the heritage language? | 4.0% | 4.3% | 15.3% | 76.3% |

| Q17 …have an overview table with a list of the most important prepositions (translations & usage) in the child’s heritage language? | 4.0% | 6.3% | 18.3% | 71.3% |

| Q20 … give the child and his/her family some homework to practice in their heritage language? | 6.7% | 7.7% | 41.7% | 43.7% |

| Q21 If such tasks were available to you, would you use them? | 4.7% | 5.7% | 26.7% | 63.0% |

| Q18 … assess the level of proficiency in the child’s heritage language with computerized tasks? | 5.3% | 5.3% | 32.7% | 56.7% |

| Q19 If such tasks existed, would you use them when working with multilingual children? | 5.0% | 4.7% | 36.0% | 54.3% |

| No | Rarely | Sometimes | Yes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q12 (German version) Do you think it would be useful to check whether the syntactic and morphological structures that cause difficulties to the child in the societal language are also affected in the heritage language? | 5.6% | 2.5% | 19.3% | 72.6% |

| Q12 (Italian version) Do you think it would be useful to check whether the syntactic and morphological structures that cause difficulties to the child in the societal language are present in the heritage language? | 1.9% | 0% | 12.6% | 85.4% |

| Question | Response Options | Austria | Germany | Italy | Switzerland |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q4 Do you believe that (A) DLD is independent of speaking a second language, or that (B) multilingualism may impact the manifestation of DLD? | A | 37.8% | 48.2% | 26.2% | 28.4% |

| more A than B | 17.8% | 20.0% | 23.3% | 35.8% | |

| more B than A | 37.8% | 22.4% | 35.9% | 22.4% | |

| B | 6.7% | 9.4% | 14.6% | 13.4% | |

| Q7 if yes/sometimes/rarely (Q6)...(A) were your comparisons based on information provided by the parents or (B) were you able to directly observe child behavior in both languages (possibly in the presence of parents)? | A | 31.1% | 30.6% | 31.1% | 32.8% |

| more A than B | 26.7% | 41.2% | 26.2% | 43.3% | |

| more B than A | 31.1% | 12.9% | 15.5% | 14.9% | |

| B | 6.7% | 14.1% | 20.4% | 9.0% | |

| Q12 Do you think it would be useful to check whether the syntactic and morphological structures that cause difficulties to the child in the societal language are present/also affected in the heritage language? | no | 8.9% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 6.0% |

| rarely | 6.7% | 2.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| sometimes | 13.3% | 20.0% | 12.6% | 22.4% | |

| yes | 71.1% | 74.1% | 85.4% | 71.6% | |

| Q14 Do you think it would be useful to check whether words that the child uses semantically/lexically incorrectly in German (i.e., the societal language) are also used incorrectly in the heritage language? | no | 4.4% | 2.3% | 0.0% | |

| rarely | 6.7% | 2.3% | 3.0% | ||

| sometimes | 6.7% | 10.6% | 25.4% | ||

| yes | 82.2% | 84.7% | 71.6% | ||

| Q20 Do you think it would be useful to give the child and his/her family tasks to take home to practice in the heritage language? | no | 11.1% | 2.4% | 8.7% | 6.0% |

| rarely | 4.4% | 10.6% | 1.9% | 14.9% | |

| sometimes | 26.7% | 47.1% | 42.7% | 43.3% | |

| yes | 57.8% | 40.0% | 45.6% | 35.8% | |

| Q21 If such tasks were available to you (Q20), would you use them? | no | 6.7% | 1.2% | 4.9% | 7.5% |

| rarely | 2.2% | 7.1% | 1.0% | 13.4% | |

| sometimes | 20.0% | 28.2% | 26.2% | 29.9% | |

| yes | 71.1% | 63.5% | 68.0% | 49.3% | |

| Q22 Do you think that differences in the languages spoken by the child and the therapist may influence the quality of the intervention? | no | 8.9% | 18.8% | 5.8% | 7.5% |

| rarely | 13.3% | 12.9% | 1.0% | 20.9% | |

| sometimes | 42.2% | 44.7% | 48.5% | 55.2% | |

| yes | 35.6% | 23.5% | 44.7% | 16.4% | |

| Q24 Do you think that cultural differences between the SLT and the child’s family influence the quality of parent consultation? | no | 11.1% | 11.8% | 2.9% | 7.3% |

| rarely | 11.1% | 11.8% | 1.9% | 8.7% | |

| sometimes | 42.2% | 42.4% | 45.6% | 45.3% | |

| yes | 35.6% | 34.1% | 48.5% | 38.3% |

| Q5 Do You Think That… | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| … It Would be Better for Multilingual Children with DLD to Speak Only One Language (Both at Home and Outside the Family Environment). | … It Would be Better for All of a Child’s Communication Partners to Interact in the Language They Know Best. | ||

| Q3 Do you think that (A) the therapy of DLD in multilingual children should be exclusively limited to the societal language, or that (B) the child’s heritage language should also be taken into account? | A | 9.7% | 2.2% |

| more A than B | 35.5% | 36.9% | |

| more B than A | 22.6% | 36.2% | |

| B | 33.3% | 24.6% | |

| Q6 In the context of SLT for multilingual children with DLD, do you think that it is useful to compare a child’s language performance in the heritage and societal language? | no | 6.9% | 1.5% |

| rarely | 6.9% | 4.5% | |

| sometimes | 41.4% | 28.0% | |

| yes | 44.8% | 66.0% | |

| Q8 Are you aware of any testing or other diagnostic material that have been developed specifically for multilingual children? | no | 61.3% | 32.7% |

| yes | 38.7% | 67.3% | |

| Q18 Do you think that computerized tasks to assess the level of proficiency in the child’s heritage language would be useful? | no | 16.1% | 4.9% |

| rarely | 9.7% | 4.8% | |

| sometimes | 19.4% | 34.2% | |

| yes | 54.8% | 56.9% | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bloder, T.; Eikerling, M.; Rinker, T.; Lorusso, M.L. Speech and Language Therapy Service for Multilingual Children: Attitudes and Approaches across Four European Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112143

Bloder T, Eikerling M, Rinker T, Lorusso ML. Speech and Language Therapy Service for Multilingual Children: Attitudes and Approaches across Four European Countries. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112143

Chicago/Turabian StyleBloder, Theresa, Maren Eikerling, Tanja Rinker, and Maria Luisa Lorusso. 2021. "Speech and Language Therapy Service for Multilingual Children: Attitudes and Approaches across Four European Countries" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112143

APA StyleBloder, T., Eikerling, M., Rinker, T., & Lorusso, M. L. (2021). Speech and Language Therapy Service for Multilingual Children: Attitudes and Approaches across Four European Countries. Sustainability, 13(21), 12143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112143