Teachers’ Social–Emotional Competence: History, Concept, Models, Instruments, and Recommendations for Educational Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What was the historical, conceptual, and theoretical path of the SEC construct?

- What are the models and measurement instruments for teachers’ SEC?

- What recommendations are pertinent for the development of teachers’ SEC as a way of contributing to educational quality?

2. Methods

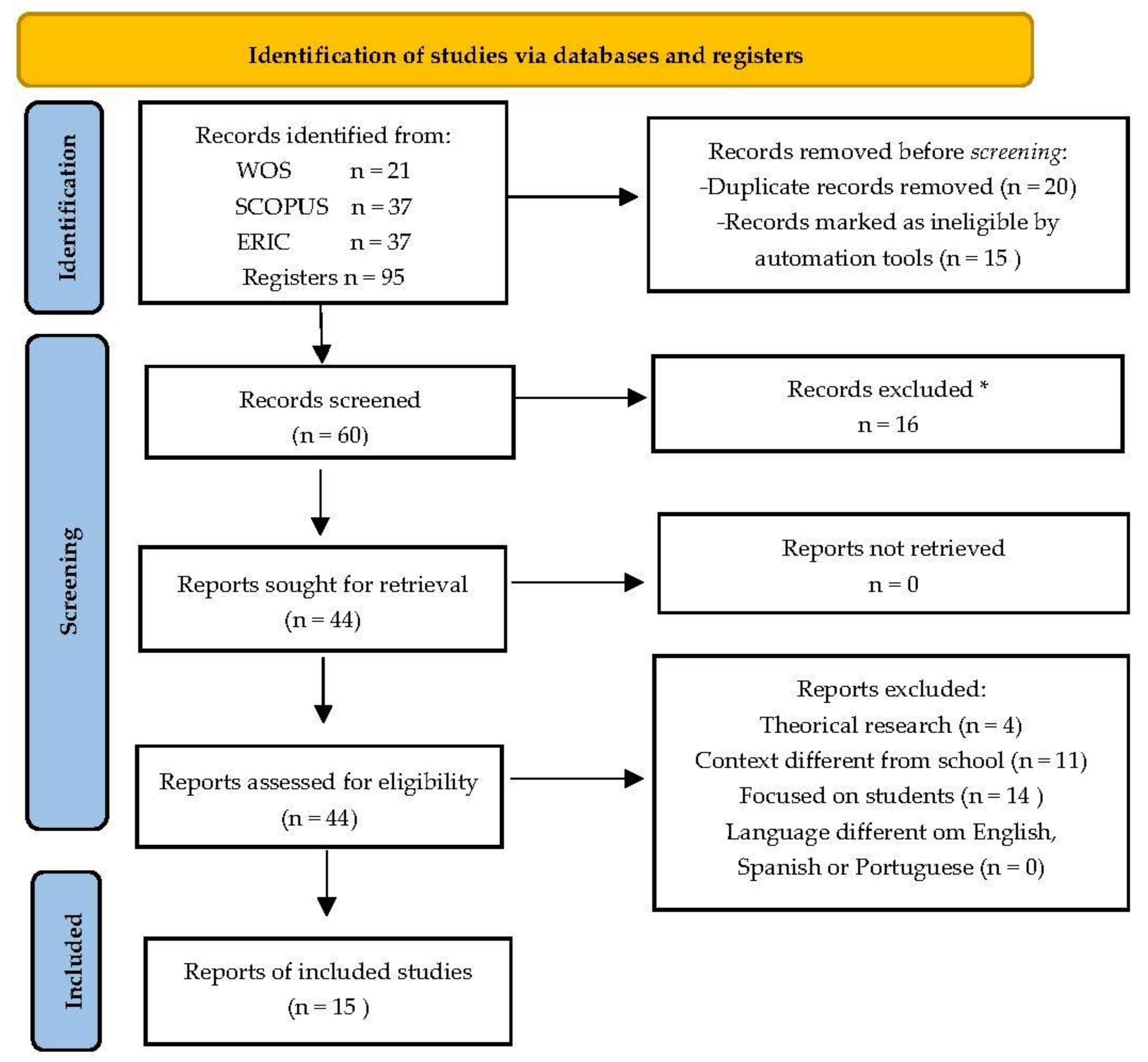

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

2.1.1. Database and Concepts Used to Form the Search Algorithm

2.1.2. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.1.3. Search Process Results

2.1.4. Study Content Analysis Process

2.2. Theoretical Review

3. Results

3.1. Historical and Conceptual Path of the SEC Construct

3.1.1. Historical SEC Path

3.1.2. Definition Path of the SEC Concept

3.2. Theoretical SEC Models and Instruments

3.2.1. Theoretical SEC Models

Emotion Regulation Process Model

Mayer and Salovey’s Emotional Intelligence Model

Bar-On’s Emotional Intelligence Model

CASEL Model

3.2.2. SEC Measurement Instruments

3.3. Recommendations for Developing Teachers’ SEC as a Way to Contribute to Educational Quality

3.3.1. Recommendations for Assessing SEC in Teachers and Their Students

3.3.2. Recommendations for Teacher Training in SEC

3.3.3. Recommendations to Strengthen the Leadership of Educational Institutions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Citation | Participants Characteristics | Socioemotional Competence Definition/or Similar Concept | Theoretical Model | Approach, Design and Sample | Instruments | Instruments Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aldrup et al. [50] | (a) Germany (b) Secondary (c) Pre/in service teachers | Social–emotional competence refers to a person’s knowledge, skills, and motivation required to master social and emotional situations. | Emotional regulation process model (Gross, 1998) | (a) Quantitative (b) Correlational (c) 346 | 1. Test of regulation and understanding of social situations in teaching (TRUST) (Authors elaboration) | (1) Emotional regulation (2) Relationship management |

| 2 | Brown et al. [51] | (a) USA (b) Primary-secondary (c) In-service teachers | Teachers’ SECs include a set of five interrelated skills: self-awareness, social awareness, self-management, relationship skills, and responsible decision making. | Social and emotional learning model (2013) | (a) Mixed (b) Not available-Correlational (c) 76 | 1. Semi-structured interviews 2. Socioemotional competence questionnaire. | (1) Self-awareness (2) Social awareness (3) Relationship management (4) Responsible decision making (5) Self-management |

| 3 | Buzgar and Giurgiuman [89] | (a) Romania (b) Primary-secondary (c) In-service teachers | Social–emotional learning refers to the process through which children and adults acquire and efficiently apply knowledge, attitudes and abilities in order to understand and control emotions, establish and achieve personal goals, feel and express empathy towards others, maintain positive relations with people, and make responsible decisions. | Not available | (a) Mixed (b) Correlational-grounded theory (c) 120 | 1. Questionnaire designed by authors | (1) Students’ age (2) Teacher’s expertise (years) (3) Teacher’s county (4) Teacher’s SEL training (5) Socioemotional learning program |

| 4 | Cheng [90] | (a) China (b) Primary-secondary (c) In-service teachers | Emotional competency is the social and emotional ability to cope with the demands of daily life. It determines how effectively individuals understand and express themselves, understand and relate to others and how they deal with everyday demands and pressures. | Bar-On Emotional intelligence model | (a) Quantitative (b) Structural equation model (predictive) (c) 958 | 1. Bar-On EQ-I | (1) Interpersonal problem solving (2) Self-actualization (3) Independent thinking (4) Stress management (5) Adaptability (6) Interpersonal relationship |

| 5 | Chica et al. [91] | (a) Colombia (b) Not available (c) In service teachers | Emotional competence: the group of knowledge, capacities, abilities and attitudes necessary in order to understand, express and regulate the emotional phenomena in an appropriate way. | Not available | (a) Qualitative (b) Multiple case study (c) 156 | 1. Field journals of student practices and discussion groups 2. Open questionnaire | (1) Emotional conscience (2) Emotional regulation (3) Emotional autonomy (4) Social competencies (5) Competencies for life and wellbeing |

| 6 | Garner [92] | (a) USA (b) Primary-secondary (c) Pre/in service teachers | Not available | Not available | (a) Quantitative (b) Hierarchical regression analysis (associative) (c) 175 | 1. Subscale of Beran 2. Dyadic Trust Scale 3. Classroom Expressiveness Questionnaire | (1) Normative beliefs (2) Assertive beliefs (3) Avoidance beliefs (4) Dismissive beliefs (5) Prosocial beliefs (6) Empathy for victims (7) Mental representations of relationships (8) Confidence about managing bullying (9) Positive expressiveness (10) Negative expressiveness |

| 7 | Hen and Goroshit [93] | (a) Israel (b) Primary–Secondary (c) Inservice teachers | Not available | Not available | (a) Quantitative (b) Structural equation model (predictive) (c) 312 | 1. Self-Efficacy Scale 2. Inter-personal Reactivity Index | (1) Understanding (2) Perceiving (3) Facilitating (4) Regulating (5) Class context (6) School context (7) Fantasy (8) Empathic concern (9) Perspective taking (10) Gender (11) Academic degree (12) Years of work experience |

| 8 | Hen and Sharabi-Nov [94] | (a) Israel (b) Primary (c) Inservice teachers | Emotional intelligence: refers to the ability to process emotional information as it pertains to the perception, assimilation, expression, regulation and management of emotion. | Emotional intelligence model. | (a) Quantitative (b) Quasi-experimental (c) 186 | 1. Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) 2. Schutte Self Report Emotional Intelligence Test (SSREIT) 3. Reflection diaries | (1) Fantasy (2) Empathic concern (3) Perspective taking (4) Personal distress (5) Empathy (6) Expression of emotion (7) Regulation of emotion (8) Management of emotion (9) Emotional Intelligence |

| 9 | Karimzadeh et al. [95] | (a) Iran (b) Primary (c) Inservice teachers | Emotional intelligence: is an ability to identify and recognize the concepts and meanings of emotions, and their interrelationships to reason them out and to solve relevant problems. | Bar-On Emotional intelligence model | (a) Quantitative (b) Experimental (c) 68 | 1. Bar-On Social–emotional Questionnaire | (1) General mood (2) Adaptive ability (3) Interpersonal ability (4) Intrapersonal ability (5) Stress management |

| 10 | Knigge et al. [70] | (a) Germany (b) Secondary (c) Preservice teachers | Not available | Prosocial classroom model | (a) Quantitative (b) Experimental (c) 323 | 1. Self report 2. Interpersonal Reactivity Index | (1) Affective attitude behavioral (2) Affective attitude learning (3) Empathic concern (4) Perspective taking (5) Emotional exhaustion (6) Goal student–teacher relationship |

| 11 | Maiors et al. [96] | (a) Romania (b) Secondary (c) Inservice teachers | Social–emotional competencies include five core competencies: self-awareness, social awareness, self-management, relationship skills, and responsible decision making. | Social and emotional learning model | (a) Quantitative (b) Correlational (c) 81 | 1. Socioemotional competence questionnaire. | (1) Basic Needs Satisfaction (2) Rational Beliefs (3) Emotional Exhaustion (4) Depersonalization (5) Personal Accomplishments (6) Social emotional competencies |

| 12 | Martzog et al. [55] | (a) Germany (b) Not available (c) Preservice teachers | Social–emotional competencies: multifaceted and include the teacher’s ability to be self-aware, to be able to recognize their own emotions and how their emotions can influence the classroom situation. | Not available | (a) Quantitative (b) Quasi-experimental (c) 148 | 1. Interpersonal Reactivity Index IRI. | (1) Empathic concern (2) Perspective taking (3) Fantasy (4) Personal distress |

| 13 | Oberle et al. [56] | (a) Canada (b) Primary (c) Inservice teachers | Teacher SEC: a comprehensive set of interrelated skills and processes, including emotional processes, social and interpersonal skills, and cognitive processes. | Prosocial classroom model | (a) Quantitative (b) Associative, predictive model (c) 35 | 1. 6-item Students’ Perceptions of Teacher Social–emotional Competence scale (TSEC) | (1) Teacher burnout (2) Classroom autonomy (3) School socioeconomic level (4) Age (5) Sex |

| 14 | Peñalva et al. [97] | (a) Spain (b) Not available (c) Preservice teachers | Emotional competence refers to the knowledge, capacities, abilities and attitudes that are considered necessary to understand, express and properly regulate emotional phenomena. | Not available | (a) Quantitative (b) Descriptive (c) 110 | 1. Emotional competence scale. | (1) Self-awareness (2) Self-regulation (3) Self-motivation (4) Empathy (5) Social skills |

| 15 | Pertegal-Felices et al. [98] | (a) Spain (b) Primary–Secondary (c) Pre/in service teachers | Emotional intelligence: is based on ability, aptitude, skill or efficiency that lead the person to a successful performance at work. | Not available | (a) Quantitative (b) Ex post facto comparative (c) 287 | 1. Traid Meta-Mood Scale-24 (TMMS-24) 2. Bar-On EQ-i:S. 3. NEO-FFI. | (1) Attention (2) Clarity (3) Repair (4) Intrapersonal intelligence (5) Interpersonal intelligence (6) Adaptability (7) Stress management (8) Humor (9) Emotional stability (10) Extroversion (11) Openness (12) Kindness (13) Responsibility |

| n° | n° Citation | Model | Core Concept | Description | Dimensions | Instruments | Use Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8926 | Emotional regulation process model [64] | Emotion regulation: is defined and distinguished from coping, mood regulation, defense, and affect regulation. Emotion is characterized in terms of response tendencies. | The emotion regulation process model facilitates the analysis of types of emotion regulation. This model has five sets of emotion regulatory processes: situation selection, situation modification, attention deployment, cognitive change, and response modulation. This is an elaboration of two-way distinction between antecedent-centered emotion regulation, which occurs before the emotion is generated, and response-centered emotion regulation, which occurs after the emotion is generated. | (a) Situation selection (b) Situation modification (c) Attentional deployment (d) Cognitive change (e) Response modulation | Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) Dimensions: (a) Cognitive reappraisal, (b) Expressive suppression | Adults Children and Adolescents |

| 2 | 2935 | Prosocial classroom model [17] | Social and emotional competence: use the broadly accepted definition of social and emotional competence developed by CASEL (2008). This definition involves five major emotional, cognitive, and behavioral competencies: self- awareness, social awareness, responsible decision making, self-management, and relationship management. | The prosocial classroom mediational model establishes teacher social and emotional competence (SEC) and wellbeing as an organizational framework that can be examined in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Teachers’ SEC and wellbeing influences the prosocial classroom atmosphere and student outcomes. This model recognizes teacher SEC as an important contributor to the development of supportive teacher–student relationships; teachers higher in SEC are likely to demonstrate more effective classroom management and they will implement a social and emotional curriculum more effectively because they are outstanding role models of desired social and emotional behavior | (a) Teacher’s social–emotional competence and wellbeing (b) Teacher–student relationships (c) Effective classroom management (d) Social–emotional learning program implementation (e) Classroom climate | Different instruments for measuring SEC, example: 1. Interpersonal Reactivity Index 2. TSEC perception scale | Adults |

| 3 | 55 | Social and emotional learning model [26] | Social and emotional learning: involves the processes through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. | CASEL has identified five interrelated sets of cognitive, affective, and behavioral competencies: self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision making, relationship skills, social awareness (CASEL, 2013). The framework takes a systemic approach that emphasizes the importance of establishing equitable learning environments and coordinating practices across key settings to enhance all students’ social, emotional, and academic learning. It is most beneficial to integrate SEL throughout the school’s academic curricula and culture, across the broader contexts of schoolwide practices and policies, and through ongoing collaboration with families and community organizations. | (a) Self-awareness (b) Self-management (c) Responsible decision making (d) Relationship skills (e) Social awareness | Socioemotional competence questionnaire Dimensions: (a) Self-awareness, (b) Self-management, (c) Responsible decision making, (d) Relationship skills, (e) Social awareness | Adults Children and Adolescents |

| 4 | 2105 | Bar-On Emotional Intelligence model [65] | Emotional intelligence: is an array of noncognitive capabilities, competencies, and skills that influence one’s ability to succeed in copying with environmental demands and pressures. | The Bar-On model provides the theoretical basis for the EQ-i, which was originally developed to assess various aspects of this construct as well as to examine its conceptualization. According to this model, emotional–social intelligence is a cross-section of interrelated emotional and social competencies, skills and facilitators that determine how effectively we understand and express ourselves, understand others and relate with them, and cope with daily demands. | (a) Intrapersonal skills (b) Interpersonal skills (c) Adaptability (d) Stress management (e) General mood | Bar-On EQ-I Dimensions: (a) Intrapersonal, (b) Interpersonal, (c) Stress management, (d) Adaptability, (e) General mood | Adults Children and Adolescents |

| 5 | 12,606 | Emotional intelligence model [25] | Emotional intelligence: is a set of abilities that account for how people’s emotional perception and understanding vary in their accuracy. More formally, we define emotional intelligence as the ability to perceive and express emotion, assimilate emotion in thought, understand and reason with emotion, and regulate emotion in the self and others. | The model considers that emotional intelligence is conceptualized through four basic skills: the ability to accurately perceive and express emotions, the ability to access and/or generate feelings that facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotions and emotional awareness and the ability to regulate emotions promoting emotional and intellectual development. | (a) Perception and expression of emotion (b) Assimilating emotion in thought (c) Understanding and analyzing emotion (d) Reflective regulation of emotion | Self-report measure: Trait Meta-Mood Scale Dimensions: (1) Attention (2) Clarity (3) Repair Performance measurement: MSCEIT Dimensions: (1) Perceiving and expressing emotions (2) Using emotions, (3) Understanding emotions, (4) Regulating emotions | Adults Children and Adolescents |

References

- Arens, K.; Morin, A. Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.; Brown, J.; Frank, J.; Doyle, S.; Oh, Y.; Davis, R.; Rasheed, D.; DeWeese, A.; DeMauro, A.A.; Cham, H.; et al. Impacts of the CARE for teachers program on teachers’ social and emotional competence and classroom interactions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 1010–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M. Students’ emotional and behavioral difficulties: The role of teachers’ social and emotional learning and teacher-student relationships. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2018, 9, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.; Denk, A.; Lubaway, E.; Sälzer, C.; Kozina, A.; Perše, T.; Rasmusson, M.; Jugović, I.; Lund Nielsen, B.; Rozman, M.; et al. Assessing social, emotional, and intercultural competences of students and school staff: A systematic literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A. Advancements in the Landscape of Social and Emotional Learning and Emerging Topics on the Horizon. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A. Social and emotional learning and teachers. Future Child 2017, 27, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissberg, R.; Durlak, J.; Domitrovich, C.; Gullotta, T. Social and Emotional Learning: Past, present, and future. In Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice, 1st ed.; Durlak, J.A., Domitrovich, C.E., Weissberg, R.P., Gullotta, T.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, T.P.; Marques-Pinto, A.; Alvarez, M.J. Estudo psicométrico da escala de avaliação dos riscos e oportunidades dos jovens utilizadores do facebook. Rev. Iberoam. Diagn. Eval. Psicol. 2016, 1, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Hernández, E. Competencias socioemocionales y creencias de autoeficacia como predictores del burnout en docentes mexicanos. Rev. Estud. Exp. Educ. 2018, 17, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.; Doyle, S.; Oh, Y.; Rasheed, D.; Frank, J.L.; Brown, J.L. Long-term impacts of the CARE program on teachers’ self-reported social and emotional competence and well-being. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 76, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.; Roberto, M.S.; Veiga-Simão, A.M.; Marques-Pinto, A. A meta-analysis of the impact of social and emotional learning interventions on teachers’ burnout symptoms. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, M.; Sutherland, K.; Algina, J.; Wilson, R.; Martinez, J.; Whalon, K. Measuring teacher implementation of the BEST-in-CLASS intervention program and corollary child outcomes. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2015, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelin, J. Enhancing pre-service teachers’ socio-emotional competence. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2019, 11, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Conroy, M.A.; Sutherland, K.S.; Algina, J.; Ladwig, C.; Werch, B.; Martinez, J.; Jessee, G.; Gyure, M.; Curby, T. Outcomes of the BEST-in-CLASS intervention on teachers’ use of effective practices, self-efficacy, and classroom quality. School Psych. Rev. 2019, 48, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, P.; Gaeta, M. La competencia socioemocional docente en el logro del aprendizaje de las competencias genéricas del perfil de egreso de educación media superior. Rev. Común. Vivat. Acad. 2016, 19, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.; Shapka, J.; Perry, N.; Martin, A. Teachers’ psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.; Greenberg, M.T. The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2009, 79, 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.M.; McGarrah, M.W.; Kahn, J. Social and Emotional Learning: A Principled Science of Human Development in Context. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLay, D.; Zhang, L.; Hanish, L.; Miller, C.F.; Fabes, R.; Martin, C.; Kochel, K.P.; Updegraff, A.A. Peer influence on academic performance: A social network analysis of social-emotional intervention effects. Prev. Sci. 2016, 17, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roorda, D.; Jak, S.; Zee, M.; Oort, F.; Koomen, H. Affective teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psych. Rev. 2017, 46, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra-Alzina, R.; Pérez-Escoda, N. Las competencias emocionales. Educ. XX1 2007, 10, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D. Emotional Intelligence: New Ability or Eclectic Traits? Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic, I.; Crespi, M.; Radusky, P. Construcción y validación del inventario de competencias socioemocionales para adultos (ICSE). Interdiscip. Rev. Psicol. Cienc. Afines 2015, 32, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, M. Difficulties in defining social-emotional intelligence, competences and skills—A theoretical analysis and structural suggestion. Int. J. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train 2015, 2, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D. Models of emotional intelligence. In The Handbook of Intelligence, 1st ed.; Stemberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 4, pp. 396–420. [Google Scholar]

- CASEL. Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs [Internet]. Preschool and Elementary School Edition. 2013. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/513f79f9e4b05ce7b70e9673/t/526a220de4b00a92c90436ba/1382687245993/2013-casel-guide.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Luo, L.; Reichow, B.; Snyder, P.; Harrington, J.; Polignano, J. Systematic review and meta-enalysis of classroom-wide social–emotional interventions for preschool children. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, T.; Darling-Churchill, K. Review of measures of social and emotional development. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 45, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.; Plötner, M.; Schmitz, J. Social competence and psychopathology in early childhood: A systematic review. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 28, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamothe, M.; Rondeau, É.; Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C.; Duval, M.; Sultan, S. Outcomes of MBSR or MBSR-based interventions in health care providers: A systematic review with a focus on empathy and emotional competencies. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 24, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puertas, P.; Ubago, J.; Moreno, R.; Padial, R.; Martínez, A.; González, G. La inteligencia emocional en la formación y desempeño docente: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2018, 29, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Robles-Bello, M. Instrumentos de evaluación en inteligencia emocional: Una revisión sistemática cuantitativa. Perspect. Educ. 2018, 57, 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Palminder, S. Towards a metodology for developing evidence-informed managament knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwary, D.A. A corpus and a concordancer of academic journal articles. Data Br. 2018, 16, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A. La Documentación Educativa en la Sociedad del Conocimiento: Actas del I Simposio Internacional de Documentación Educativa. Revisión Documental en las Bases de Datos Educativas: Un Análisis de la Documentación Disponible Sobre Evaluación de la Transferencia de los Aprendizajes. Available online: https://redined.mecd.gob.es/xmlui/handle/11162/5539 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Kihlstrom, J.; Cantor, N. Social intelligence. In The Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence, 1st ed.; Sternberg, R., Kaufman, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 564–581. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, M.; Rivas, L. Orígenes, evolución y modelos de inteligencia emocional. Innovar 2005, 15, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Zins, J.; Weissberg, R.; Frey, K.; Greenberg, M.; Haynes, N.; Kessler, R.; Schwab-Stone, M.E.; Shriver, T.P. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators, 1st ed.; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1997; pp. 1–164. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J.; Weissberg, R.; Greenberg, M.; Dusenbury, L.; Jagers, R.; Niemi, K.; Schlinger, M.; Schlund, J.; Shriver, T.P.; Van Ausdal, K.; et al. Systemic Social and Emotional Learning: Promoting Educational Success for All Preschool to High School Students. Am. Psychol. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC). Available online: http://www.iisue.unam.mx/boletin/?p=2472 (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Miller, A.L.; Fine, S.E.; Gouley, K.K.; Seifer, R.; Dickstein, S.; Shields, A. Showing and telling about emotions: Interrelations between facets of emotional competence and associations with classroom adjustment in Head Start preschoolers. Cogn. Emot. 2006, 20, 1170–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, M. Students’ perceptions of female professors. J. Vocat. Behav. 1976, 8, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoiber, K.; Anderson, A.J. Behavioral assessment of coping strategies in young children at-risk, developmentally delayed, and typically developing. Early Educ. Dev. 1996, 7, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, B.E. Effects of Day-Care on Cognitive and Socioemotional Competence of Thirteen-Year-Old Swedish Schoolchildren. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. The development of social and emotional competence at school: An integrated model. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2019, 44, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrup, K.; Carstensen, B.; Köller, M.; Klusmann, U. Measuring teachers’ social-emotional competence: Development and validation of a situational judgment test. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.L.; Valenti, M.; Sweet, T.; Mahatmya, D.; Celedonia, K.; Bethea, C. How Social and Emotional Competencies Inform Special Educators’ Social Networks. Educ. Treat. Child. 2020, 43, 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, M.L.; Williams, B.V.; May, T. Early Childhood Teachers’ Perspectives on Social-Emotional Competence and Learning in Urban Classrooms. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 34, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Osher, D.; Same, M.R.; Nolan, E.; Benson, D.; Jacobs, N. Identifying, Defining, and Measuring Social and Emotional Competencies, 1st ed.; American Institutes For Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–252. [Google Scholar]

- Llorent, V.J.; Zych, I.; Varo-Millán, J.C. Social and emotional competences self-perceived by the university professors in Spain. Educ. XX1 2020, 23, 297–318. [Google Scholar]

- Martzog, P.; Kuttner, S.; Pollak, G. A comparison of Waldorf and non-Waldorf student-teachers’ social-emotional competencies: Can arts engagement explain differences? J. Educ. Teach. 2016, 42, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberle, E.; Gist, A.; Cooray, M.S.; Pinto, J.B. Do students notice stress in teachers? Associations between classroom teacher burnout and students’ perceptions of teacher social-emotional competence. Psychol. Sch. 2020, 57, 1741–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, A. Educación de la competencia socioemocional y estilos de enseñanza en la educación media. Sophia—Educ. 2015, 11, 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, Á.; Celis, L.; Blandón, O. Las competencias docentes profesionales: Una revisión del sentido desde diferentes perspectivas. Rev. Educ. Pensam. 2017, 24, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci, S.; Barnett, S.; Kanaya, T. Developing childhood proclivities into adult competencies: The overlooked multiplier effect. In The Psychology of Abilities, Competencies, and Expertise; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, D.; Vasco, C. Habilidades, Competencias y Experticias: Más Allá del Saber qué y el Saber Cómo, 1st ed.; Unitec: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013; pp. 1–179. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert, F. Competencies and key competencies: Educational perspective. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1st ed.; Smelser, N., Baltes, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Competency Framework [Internet]. Talent.oecd. 2014. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/careers/competency_framework_en.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Gross, J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R. The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI). Psicothema 2006, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; Carstensen, L.L.; Pasupathi, M.; Tsai, J.; Götestam-Skorpen, C.; Hsu, A.Y. Emotion and aging: Experience, expression, and control. Psychol. Aging 1997, 12, 590–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J.; Muñoz, R.F. Emotion Regulation and Mental Health. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Prac. 1995, 2, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, G.; Oudsten, B. Emotional intelligence: Relationships to stress, health, and well-being. In Emotion Regulation, 1st ed.; Vingerhoets, A., Nyklíček, I., Denollet, J., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- CASEL. CASEL’S SEL FRAMEWORK: What Are the Core Competence Areas and Where Are They Promoted? Available online: https://casel.org/casel-sel-framework-11-2020/ (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Yoder, N. Self-Assessing Social and Emotional Instruction and Competencies: A Tool for Teachers [Internet]. Center on Great Teachers and Leaders. Washington: American Institutes for Research. 2014, pp. 1–30. Available online: https://www.lib.uwo.ca/cgi-bin/ezpauthn.cgi?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1697492666?accountid=15115%0Ahttp://vr2pk9sx9w.search.serialssolutions.com?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/ERIC&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev: (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Knigge, M.; Krauskopf, K.; Wagner, S. Improving socio-emotional competencies using a staged video-based learning program? results of two experimental studies. Front. Educ. 2019, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.; Weissberg, R.; Dymnicki, A.; Taylor, R.; Schellinger, K. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child. Dev. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKown, C. Challenges and opportunities in the applied assessment of student social and emotional learning. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKown, C. Student Social and Emotional Competence Assessment: The Current State of the Field and a Vision for Its Future; CASEL: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mckown, C. Social-Emotional Assessment, Performance, and Standards. Future Child 2017, 2, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Kitil, M.J.; Hanson-Peterson, J. Building a Foundation for Great Teaching; A Report Prepared for CASEL; CASEL: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, V.; Lloyd, C.; Rowe, K. El impacto del liderazgo en los resultados de los estudiantes: Un análisis de los efectos diferenciales de los tipos de liderazgo. REICE Rev. Electrón. Iberoam. Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2014, 12, 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, J.; Muñoz, G. ¿Qué Sabemos Sobre los Directores en Chile, 1st ed.; Centro de Innovación en Educación de Fundación Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2012; pp. 1–456. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco-Sáez, A.; González-Martínez, P. Liderazgo para la inclusión y para la justicia social: El desafío del liderazgo directivo ante la implementación de la Ley de Inclusión Escolar en Chile. Rev. Educ. Ciudad. 2017, 33, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C.; Durlak, J.; Staley, K.; Weissberg, R. Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Suárez, A.; Herrero, J.; Pérez, B.; Juarros-Basterretxea, J.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F. Risk Factors for School Dropout in a Sample of Juvenile Offenders. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L.; Belsky, D.; Dickson, N.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.L.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Roberts, B.W.; Ross, S.; et al. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2693–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentacosta, C.; Fine, S. Emotion knowledge, social competence, and behavior problems in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A. Emotional Intelligence: An Integrative Meta-Analysis and Cascading Model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic, I.; Caballero, R.; Vizioli, N.; Hurtado, G. II Congreso de Internacional de Psicología—V Congreso Nacional de Psicología Ciencia y Profesión. Estudio de las Competencias Socioemocionales en Diferentes Etapas Vitales. Argentina: Anuario de investigaciones. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321144339_Estudio_de_las_Competencias_Socioemocionales_en_Diferentes_Etapas_Vitales (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Cassullo, G.L.; García, L. Estudio de las ocmpetencias socio emocionales y su relación con el afrontamiento en futuros profesores de nivel medio. Rev. Electrón. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2015, 18, 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalyn, T. Measuarement of Teachers’Social-Emotional Competence: Development of the Social Emotional Competence Teacher Rating Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wigelsworth, M.; Lendrum, A.; Oldfield, J.; Scott, A.; Bokkel, I.; Tate, K.; Emery, C. The impact of trial stage, developer involvement and international transferability on universal social and emotional learning programme outcomes: A meta-analysis. Camb. J. Educ. 2016, 46, 347–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzgar, R.; Giurgiuman, T. Teaching social and emotional competencies: A pilot survey on social and emotional learning programs implemented in Romania. J. Educ. Sci. Psychol. 2019, 9, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, E. Management strategies for developing teachers’ emotional competency. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2013, 7, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica, O.; Sánchez, J.; Pacheco, A. A look at teacher training in Colombia: The utopia of emotional training. Utop. Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, P. The role of teachers’ social-emotional competence in their beliefs about peer victimization. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2017, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, M.; Goroshit, M. Social–emotional competencies among teachers: An examination of interrelationships. Cogent. Educ. 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hen, M.; Sharabi-Nov, A. Teaching the teachers: Emotional intelligence training for teachers. Teach. Educ. 2014, 25, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, M.; Salehi, H.; Embi, M.; Nasiri, M.; Shojaee, M. Teaching efficacy in the classroom: Skill based training for teachers’ empowerment. English Lang. Teach. 2014, 7, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maiors, E.; Dobrean, A.; Păsărelu, C.R. Teacher rationality, social-emotional competencies and basic needs satisfaction: Direct and indirect effects on teacher burnout. J. Evid.-Based Psychother. 2020, 20, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñalva, A.; López, J.; Landa, N. Competencias emocionales del alumnado de Magisterio: Posibles implicaciones profesionales. Rev. Educ. 2013, 362, 690–712. [Google Scholar]

- Pertegal-Felices, M.; Castejón-Costa, J.; Martínez, M. Competencias socioemocionales en el desarrollo profesional del maestro. Educ. XX1 2011, 14, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Social–Emotional Competence Definition |

|---|---|

| 1997 | Social–emotional competence refers to a person’s knowledge, skills, and motivation required to master social and emotional situations. |

| 2002 | A multivariate concept that includes a person’s ability to identify their emotions, to be able to manage their emotions appropriately, to have positive interactions, and to have positive interactions with others. |

| 2003 | A set of social and emotional skills to achieve a goal both in the personal and professional spheres. |

| 2007 | The ability to appropriately mobilize a set of knowledge, skills, abilities and attitudes to perform different activities with a certain level of quality and efficiency. |

| 2009 | A comprehensive set of interrelated skills and processes, including emotional processes (e.g., understanding and regulating emotions, taking others’ perspectives, recognizing their own emotional strengths and weaknesses), social and interpersonal skills (e.g., understanding social cues and interacting positively with others), and cognitive processes (e.g., stress management, impulse control). |

| 2011 | A multidimensional concept, cognitive, attitudinal and behavioral, and it involves uncertainty. |

| 2012 | Knowledge, skills and social and emotional attitudes, put into practice in real life. |

| 2013 | Teacher SEC is understood as a comprehensive set of interrelated skills and processes, including emotional processes (e.g., understanding and regulating emotions, taking others’ perspectives, recognizing their own emotional strengths and weaknesses), social and interpersonal skills (e.g., understanding social cues and interacting positively with others), and cognitive processes (e.g., stress management, impulse control.) |

| 2017 | Skills, knowledge, attitudes, and social and emotional dispositions that enable a person to set goals, manage behavior, build relationships, and process information in diverse contexts that intentionally develop these competencies. |

| 2019 | Teacher SEC is defined in terms of the five competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills and responsible decision making. |

| 2020 | Effective management of intrapersonal and interpersonal social and emotional experiences in ways that foster one’s own and others’ thriving. SEC is operationalized by individuals’ social–emotional basic psychological need satisfaction, motivations, and behaviors. |

| Emotional Intelligence Models | Emotional Regulation Model | Social–Emotional Development Models | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayer and Salovey (1997) Emotional intelligence model | Bar-On (1997) Bar-On emotional intelligence model | Gross (1998) Emotional regulation process model | Jennings and Greenberg (2009) Prosocial classroom model | CASEL (2013) Social and emotional learning model |

| Definition Emotional intelligence: is a set of abilities that account for how people’s emotional perception and understanding vary in their accuracy. More formally, we define emotional intelligence as the ability to perceive and express emotion, assimilate emotion in thought, understand and reason with emotion, and regulate emotion in the self and others. | Definition Emotional intelligence: is an array of noncognitive capabilities, competencies, and skills that influence one’s ability to succeed in copying with environmental demands and pressures. | Definition Emotional regulation: is defined and distinguished from coping, mood regulation, defense, and affect regulation. Emotion is characterized in terms of response tendencies. | Definition: Social and emotional competence: use the broadly accepted definition of social and emotional competence developed by CASEL. This definition involves five major emotional, cognitive, and behavioral competencies: self- awareness, social awareness, responsible decision making, self-management, and relationship management. | Definition: Social and emotional learning: involves the processes through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. |

| Major areas of skills Perception and expression of emotion Assimilating emotion in thought Understanding and analyzing emotion Reflective regulation of emotion | Major areas of skills Intrapersonal skills Interpersonal skills Adaptability scales Stress-Management scalesGeneral Mood | Major areas of skills Situation selection Situation modification Attentional deployment Cognitive change Response modulation | Major areas of skills Teacher’s social–emotional competence and wellbeing Teacher–student relationships Effective classroom management Social–emotional learning program implementation Classroom climate | Major areas of skills Self-awareness Self-management Responsible decision making Relationship skills Social awareness |

| n° citation 12,606 | n° citation 2015 | n° citation 8926 | n° citation 2935 | n° citation 55 |

| Model | Measuring Instrument | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional regulation process model [63] | Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) Dimensions:

| Adults Children and teenagers |

| Prosocial classroom model [17] | Different instruments for measuring SEC, example:

| Adults |

| Social and emotional learning model [26] | Socioemotional competence questionnaire Dimensions:

| Adults Children and teenagers |

| Bar-On Emotional intelligence model [64] | Bar-On EQ-I Dimensions

| Adults Children and teenagers |

| Emotional intelligence model [25] |

Trait Meta-Mood Scale Dimensions:

MSCEIT Dimensions

| Adults Children and teenagers |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lozano-Peña, G.; Sáez-Delgado, F.; López-Angulo, Y.; Mella-Norambuena, J. Teachers’ Social–Emotional Competence: History, Concept, Models, Instruments, and Recommendations for Educational Quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112142

Lozano-Peña G, Sáez-Delgado F, López-Angulo Y, Mella-Norambuena J. Teachers’ Social–Emotional Competence: History, Concept, Models, Instruments, and Recommendations for Educational Quality. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112142

Chicago/Turabian StyleLozano-Peña, Gissela, Fabiola Sáez-Delgado, Yaranay López-Angulo, and Javier Mella-Norambuena. 2021. "Teachers’ Social–Emotional Competence: History, Concept, Models, Instruments, and Recommendations for Educational Quality" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112142

APA StyleLozano-Peña, G., Sáez-Delgado, F., López-Angulo, Y., & Mella-Norambuena, J. (2021). Teachers’ Social–Emotional Competence: History, Concept, Models, Instruments, and Recommendations for Educational Quality. Sustainability, 13(21), 12142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112142