Banks and Climate-Related Information: The Case of Portugal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

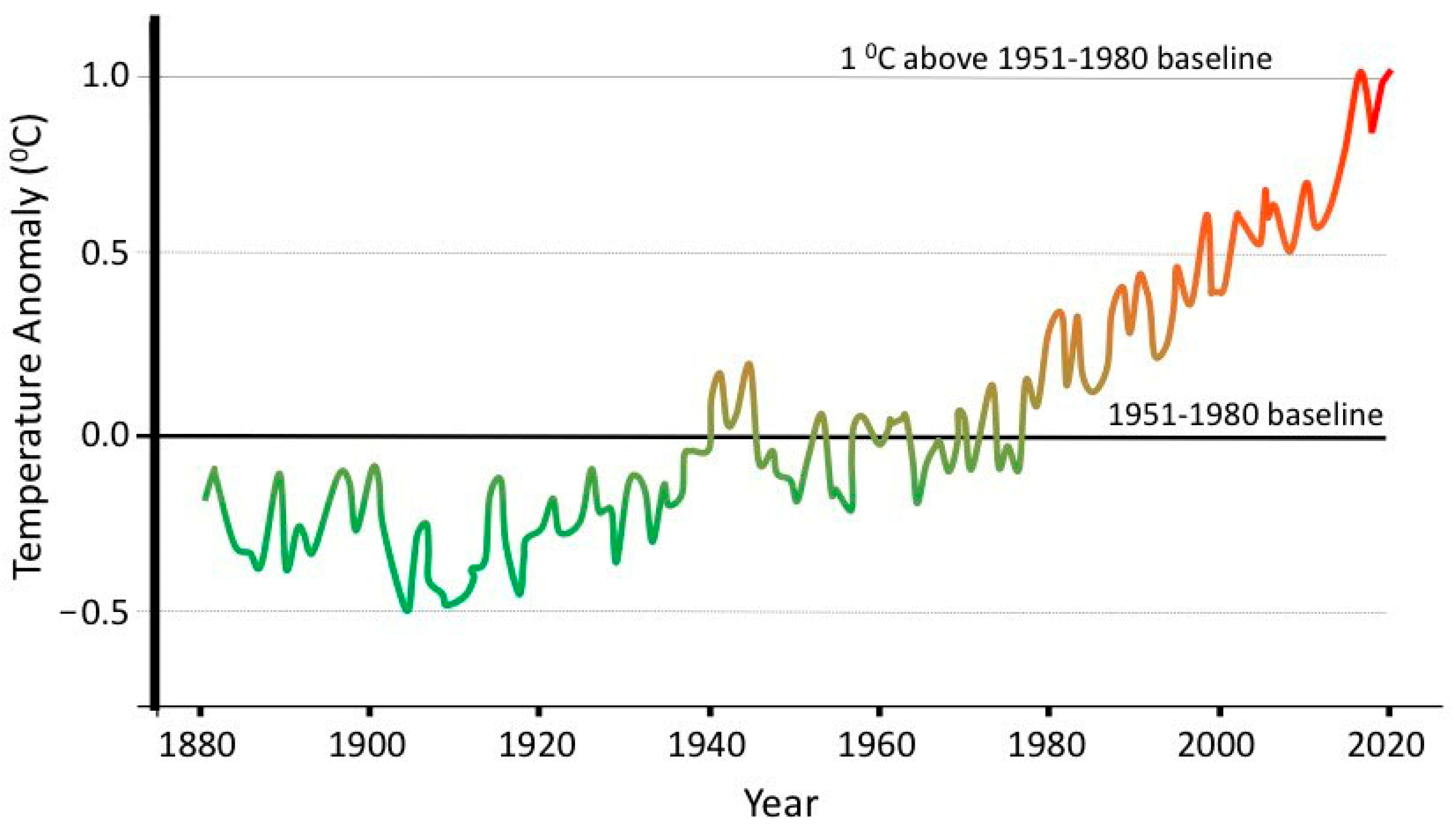

2.1. The Growing Importance of Banks in Climate Change

2.2. Regulations, Banks and Climate Change

- information about the expected impact of climate change on its strategies and activities;

- relevant governance aspects, including board oversight on matters related to climate change;

- information on who is responsible for setting, implementing, and monitoring a specific policy on climate-related matters. They may also describe the role and responsibility of the board/supervisory board regarding environmental, social, and human rights policies;

- material information on climate-related impacts on their operations and strategy, including appropriate assessments of likelihood and use of scenario analyses; and

- the appropriate disclosures on metrics and targets that are used to assess and manage relevant environmental and climate-related matters.

- unified classification system for sustainable economic activities (taxonomy);

- EU green bond standard;

- benchmarks for low-carbon investment strategies;

- new guidelines on the reporting of climate-related information.

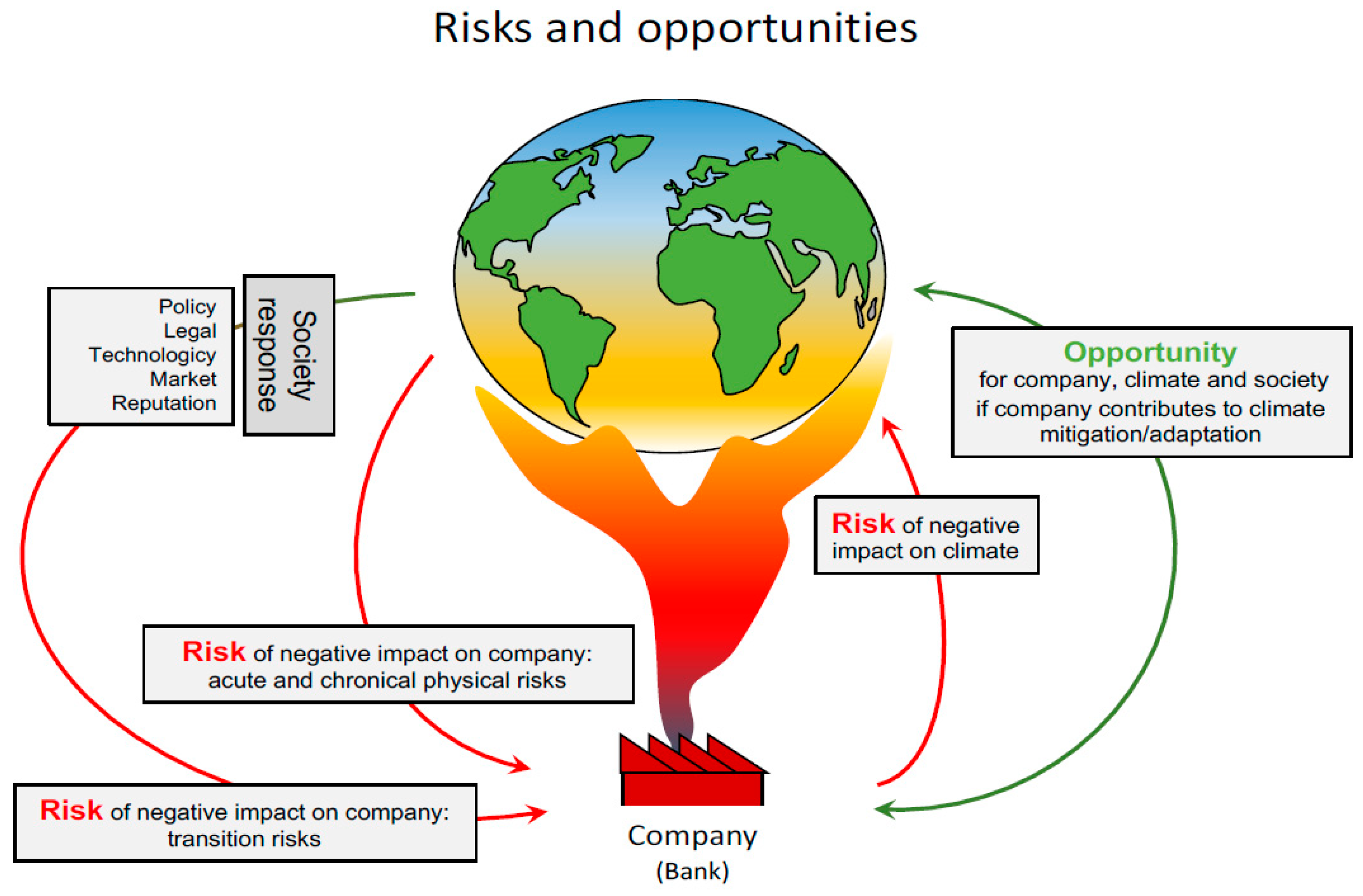

- physical risks (arising from the physical effects of climate change, including liability risks for contributing to it);

- transition risks (arising from the transition to a low-carbon and climate-resistant economy);

- other risks (for example, changes in the market and consumer preferences and legal risks that may affect the performance of the underlying assets).

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Content Analysis and Evaluation Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Evolution of Climate-Related Information

4.2. Approach Adopted by Banks on Climate-Related Information for 2017–2019

4.2.1. Disclosure on Business Model

4.2.2. Disclosure on Policies and Due Diligence Processes

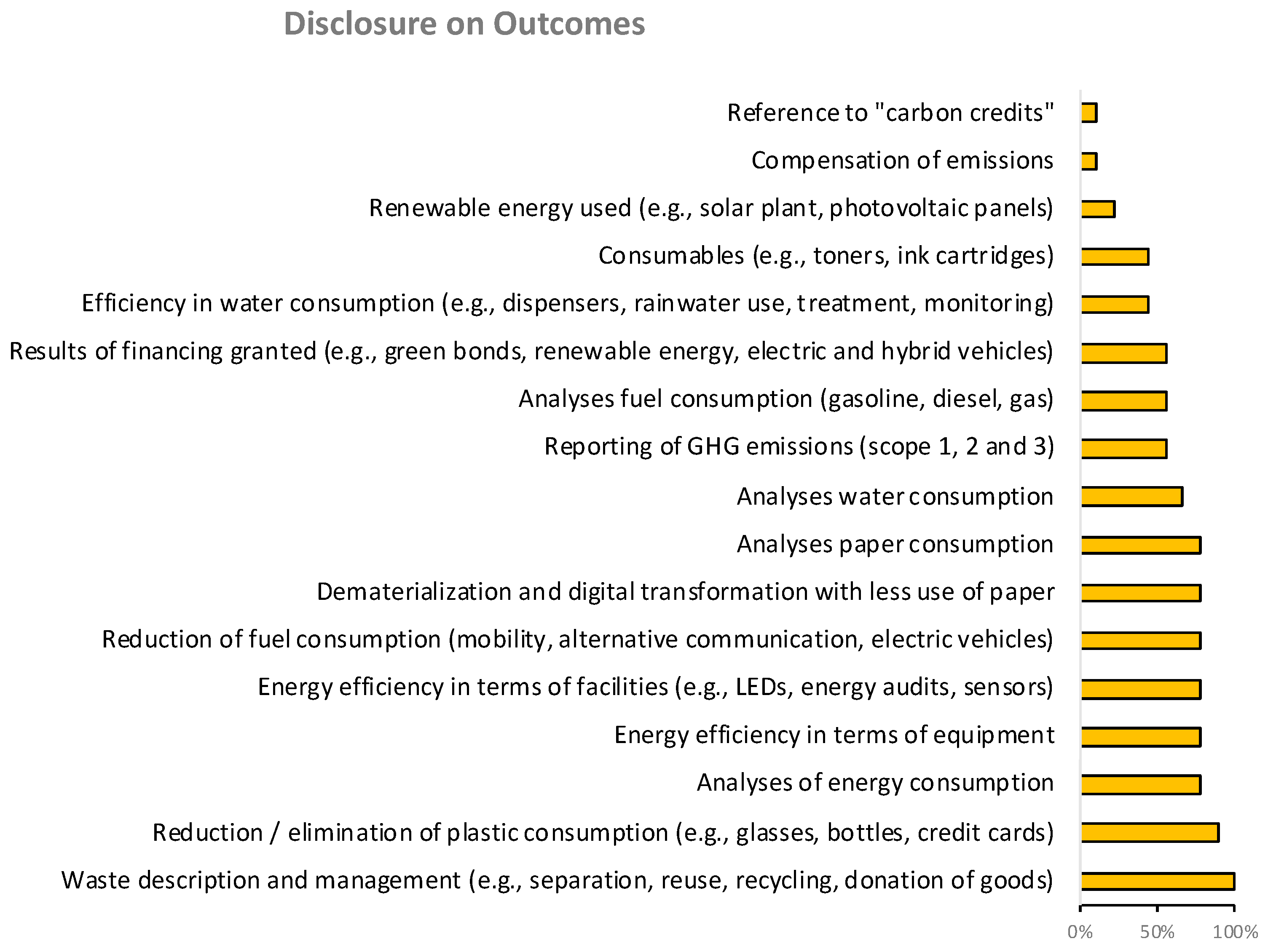

4.2.3. Disclosure on Outcomes

4.2.4. Disclosure on Principal Risks and Their Management

4.2.5. Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s)

5. Discussion

- building models of climate scenarios to support financial risk analysis;

- developing data and analysis for climate risk analysis at the level of borrowers;

- improving the methodology for the impact assessment of the portfolio; and

- integrating transition risk assessment in the organization.

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Overview: Weather, Global Warming and Climate Change. California, USA, 2021. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/resources/global-warming-vs-climate-change/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Bowman, M. The Role of the Banking Industry in Facilitating Climate Change Mitigation and the Transition to a Low-Carbon Global Economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 27, 448–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, D.G. Corporate Governance and Climate Change: The Banking Sector; Ceres: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU—European Parliament and the Council. Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council—of 22 October 2014—Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, L330, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- EU—European Commission. Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting (Methodology for Reporting Non-Financial Information). Off. J. Eur. Union 2017, C215, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- EU—European Commission. Communication from the Commission Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting: Supplement on Reporting Climate-Related Information. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, C209, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Carbon Dioxide. California, USA, 2019. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Climate Change: How Do We Know? California, USA, 2019. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/evidence/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 1–151. [Google Scholar]

- UN (United Nations—Climate Change). Guterres: Climate Action Is a “Battle for Our Lives”. Bonn, Germany, 2019. Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/guterres-climate-action-is-a-battle-for-our-lives (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- Stephens, C.; Skinner, C. Banks for a better planet? The challenge of sustainable social and environmental development and the emerging response of the banking sector. Environ. Dev. 2013, 5, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, D.; Tilburg, R.V. Financial Risks and Opportunities in the Time of Climate Change. Bruegel Policy Brief 2016, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ryszawska, B.; Zabawa, J. The Environmental Responsibility of the World’s Largest Banks. Econ. Bus. 2018, 32, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- RP (República Portuguesa). Decreto-Lei n.º 89/2017 de 28 de Julho. Diário da República 2017, 1.ª Série—N.º 145 de 28 de Julho de, 2017. pp. 4267–4271. Available online: https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/107773645/details/maximized (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- RP (República Portuguesa). Lei n.º 148/2015 de 9 de Setembro. Diário da República 2015, 1.ª Série—N.º 176 de 9 de Setembro de, 2015. pp. 7501–7516. Available online: https://dre.pt/home/-/dre/70237676/details/maximized (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- EU—European Commission. Consultation Document on the Update of the Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting. Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/consultations/finance-2019-non-financial-reporting-guidelines_en (accessed on 23 December 2019).

- EU—European Commission. Sustainable Finance: Making the Financial Sector a Powerful Actor in Fighting Climate Change. Brussels, Belgium, 2018. Available online: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-3729_en.htm?locale=en (accessed on 6 December 2019).

- TEG (Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance). Financing a Sustainable European Economy—Report on Climate-Related Disclosures; EU Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; 50p. [Google Scholar]

- EU—European Commission (Banking and Finance). Targeted Consultation on the Update of the Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting. Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://www.eciia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ECIIA-reaction-Targeted-consultation-on-the-update-of-the-non-binding-guidelines-on-non-financial-reporting-.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2019).

- EU—European Commission. Summary Report of the Targeted Consultation on the Update of the Non-Binding Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting (20 February–20 March 2019); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, J. Implementing the Kyoto Mechanisms: Potential Contributions by Banks and Insurance Companies. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.—Issues Pract. 2000, 25, 602–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaglia, P. Transforming the EU Financial Sector into a Powerful Actor in Promoting Sustainability. Fond. Eni Enrico Mattei FEEM 2019, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Batten, S.; Sowerbutts, R.; Tanaka, M. Let’s Talk about the Weather: The Impact of Climate Change on Central Banks; Bank of England Working Paper N.º603; Bank of England: London, UK, 2016; 38p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeffery, C.; Tenwick, J.; Bicciolo, G. Comparing the Implementation of the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive in the UK, Germany, France and Italy; Frank Bold: Brno, Czech Republic, 2017; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Matuszak, Ł.; Różańska, E. CSR Disclosure in Polish-Listed Companies in the Light of Directive 2014/95/EU Requirements: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNEP FI (Finance Initiative). Navigating a New Climate; UNEP Finance Initiative—Acclimatise: Genève, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Campiglio, E.; Dafermos, Y.; Monnin, P.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Schotten, G.; Tanaka, M. Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBA (European Banking Authority). Final Report—Guidelines on Loan Origination and Monitoring; EBA/GL/2020/06; European Banking Authority: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Feridun, M.; Güngör, H. Climate-Related Prudential Risks in the Banking Sector: A Review of the Emerging Regulatory and Supervisory Practices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco de Portugal. Banco de Portugal—Instituições Autorizadas. Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. Available online: https://www.bportugal.pt/entidades-autorizadas/67/all (accessed on 21 December 2019).

- Carini, C.; Rocca, L.; Veneziani, M.; Teodori, C. Ex-Ante Impact Assessment of Sustainability Information–The Directive 2014/95. Sustainability 2018, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L. Corporate Social Responsibility and Resource-Based Perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, M.; Kuzey, C. Determinants of climate change disclosures in the Turkish banking industry. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 901–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, S.; Rigot, S.; Borie, S. A New Measure of Environmental Reporting Practice Based on the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. In Proceedings of the AFC 2019, Paris, France, 9–17 May 2019; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Demaria, S.; Rigot, S. Corporate environmental reporting: Are French firms compliant with the Task Force on Climate Financial Disclosures’ recommendations? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 30, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Nicolò, G.; Zanellato, G. Ensuring More Sustainable Reporting in Europe Using Non-Financial Disclosure—De Facto and De Jure Evidence. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ECB (European Central Bank). ECB Report on Institutions’ Climate-Related and Environmental Risk Disclosures (November 2020); ECB: Frankfurt, Germany, 2020; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer, B.; Hamprecht, J.; Hoffmann, V.H. Much Ado About Nothing? How Banks Respond to Climate Change. Bus. Soc. 2012, 51, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRIS (Grupo de Reflexão para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável). Carta de Compromisso para o Financiamento Sustentável em Portugal. Lisboa, 2019. Available online: https://www.fundoambiental.pt/ficheiros/b-carta_compromissos_web_final-pdf.aspx (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- EPs (Equator Principles). The Equator Principles EP4: July 2020; The Equator Principles Association: Eastbourne, UK, 2020; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, M.J. Banks, climate risk and financial stability. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2019, 27, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, E.; Mirasgedis, S.; Sarafidis, Y.; Hontou, V.; Gakis, N.; Lalas, D.; Xenoyianni, F.; Kakavoulis, N.; Dimopoulos, D.; Zavras, V. A methodological framework and tool for assessing the climate change related risks in the banking sector. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 874–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BPI (Banco Português de Investimento, SA). Relatório e Contas—Banco BPI 2019; Banco Português de Investimento: Porto, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–510. [Google Scholar]

- BNPPPF (Banco BNP Paribas Personal Finance, SA). Demonstrações Financeiras e Notas às Contas a 31 de Dezembro de 2019 Do Banco BNP Paribas Personal Finance, SA; Banco BNP Paribas Personal Finance: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- MILLENNIUM BCP (Banco Comercial Português, SA). Relatório de Sustentabilidade 2019; Banco Comercial Português: Porto, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- CGD (Caixa Geral de Depósitos, SA). 2019 Relatório de Gestão e Contas; Caixa Geral de Depósitos: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–793. [Google Scholar]

- NOVO BANCO (Novo Banco, SA). Relatório de Sustentabilidades 2019; Novo Banco: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- SANTANDER (Banco Santander Totta, SA). Relatório de Banca Responsável 2019; Banco Santander Totta: Lisbon, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, M. Transparency of Climate-Related Risks and Opportunities: Determinants Influencing the Disclosure in Line with the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures. Glocality 2021, 4, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TCFD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures). Implementing the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climated-Related Financial Disclosures; Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G.; Krzus, M.P. Implementing the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures Recommendations: An Assessment of Corporate Readiness. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2019, 71, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EU—European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Volume 104, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Monasterolo, I.; Ulrich, V. Addressing Climate-Related Financial Risks and Overcoming Barriers to Scaling-up Sustainable Investment. In Proceedings of the G20 Insights 2020, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 31 October–1 November 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Thistlethwaite, J. The Challenges of Counting Climate Change Risks in Financial Markets; Centre for International Governance Innovation: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2015; Volume 62, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- De Bernardi, P.; Venuti, F.; Bertello, A. The Relevance of Climate Change Related Risks on Corporate Financial and Non-Financial Disclosure in Italian Listed Companies. In The Future of Risk Management Palgrave Macmillan; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strano, E.; Kabli, A. Non-Financial Reporting in Banks: Emerging Trends in Italy. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Social Sciences, Rome, Italy, 18–19 June 2018; Volume 2, pp. 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, A. Climate-Related Financial Disclosures: What Next for Environmental Sustainability? Univ. Oslo Fac. Law Leg. Stud. Res. Pap. Ser. 2018, 120, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- MBIE (Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment). Mandatory Climate-Related Disclosures. Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment. Wellington, New Zealand. 2021. Available online: https://www.mbie.govt.nz/business-and-employment/business/regulating-entities/mandatory-climate-related-disclosures/ (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Camilleri, M. Environmental, social and governance disclosures in Europe. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2015, 6, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasodomska, J.; Michalak, J.; Świetla, K. Directive 2014/95/EU: Accountants’ Understanding and Attitude towards Manda-tory Non-Financial Disclosures in Corporate Reporting. Meditari Account. Res. 2020, 28, 751–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.; Bartosch, J.; Avetisyan, E.; Kinderman, D.; Knudsen, J.S. Mandatory Non-financial Disclosure and Its Influence on CSR: An International Comparison. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 162, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizcarra, H.V. The Reasonable Investor and Climate-Related Information: Changing Expectations for Financial Disclosures. Environ. Law Rep. 2020, 50, 10106–10114. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP FI (Finance Initiative). Extending Our Horizons; UNEP Finance Initiative: Genève, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, O.; Kholodova, O. Climate Change and the Canadian Financial Sector; Center for International Governance Innovation Papers: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017; Volume 134, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- TCFD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures). Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures—2020 Status Report; TCFD: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, A.L.; Rodrigues, L.L. Banks and Climate-Related Information: The Case of Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112215

Santos AL, Rodrigues LL. Banks and Climate-Related Information: The Case of Portugal. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112215

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Aldina Lopes, and Lúcia Lima Rodrigues. 2021. "Banks and Climate-Related Information: The Case of Portugal" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112215

APA StyleSantos, A. L., & Rodrigues, L. L. (2021). Banks and Climate-Related Information: The Case of Portugal. Sustainability, 13(21), 12215. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112215