The Village Fund Program in Indonesia: Measuring the Effectiveness and Alignment to Sustainable Development Goals

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Program Overview

2.1. SDGs in Indonesia

2.2. The Village Fund Program

2.3. The Village Fund Program and Its Related Regulations

- Justice: prioritizing the rights and interests of all village residents without discrimination.

- Priority needs: prioritizing the village’s more urgent interests.

- Village authority: prioritizing the authority of the rights of origin and local authority at the village scale.

- Participative: prioritizing community initiative and creativity.

- Self-management and based on village resources: implementation independently with the utilization of village natural and local resources.

- Typology of the Village: considering geographical, sociological, anthropological, economic, and ecological characteristics. Based on the Regulation of The Minister of Village, Number 2/2016, there are five categories: Independent, Advanced, Developing, Disadvantaged and Very Disadvantaged.

2.4. Village SDGs

3. Literature Review

3.1. Previous Studies on the Village Fund and SDGs

3.2. SDG Financing through the Village Fund

3.3. Village Development Programs in Other Countries

3.4. Comparison of Evaluation Methodologies Used in Previous Studies of Other Village-Related Funds

4. Methodology

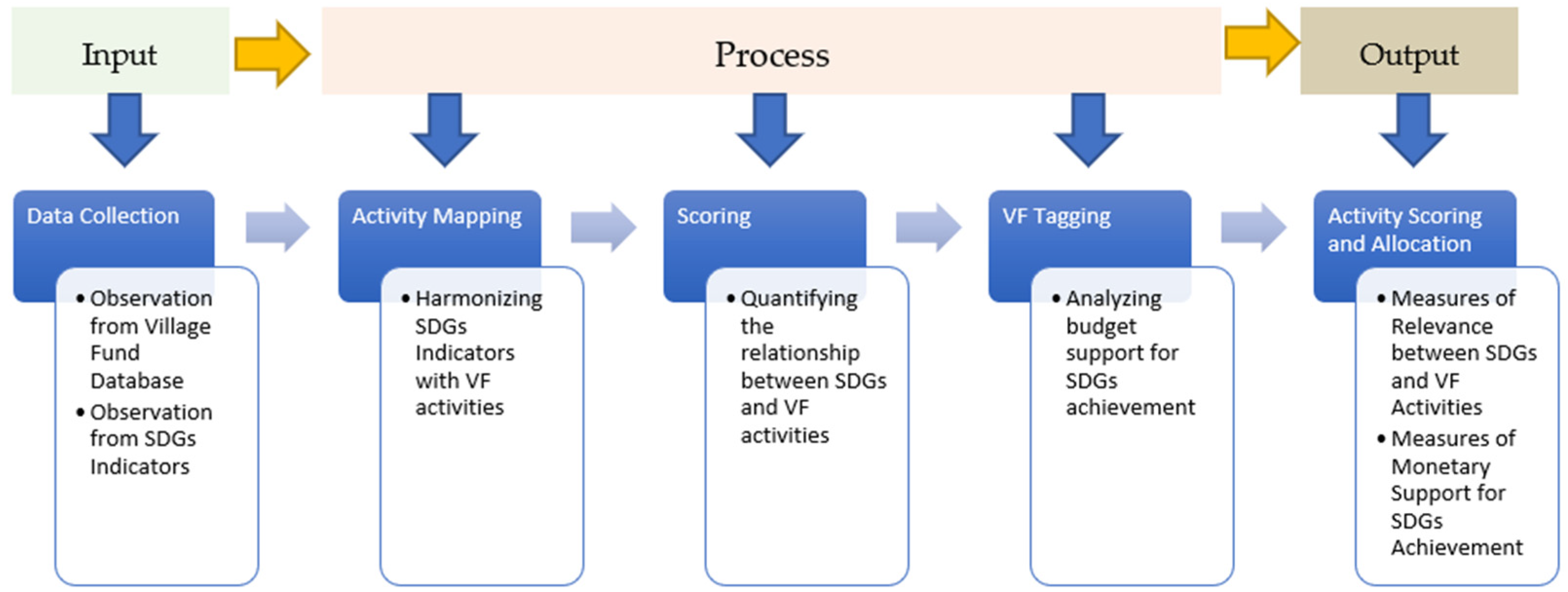

4.1. Research Design

- Objective, defined as a goal of the measurement task or basic question.

- Condition, defined as a set of circumstances, behaviors or processes that are relevant and necessary to achieve the objective.

- Theory, a sound underlying theory that supports the credibility of a framework. The theory needs to explain how the condition affects the objective.

- A state indicator or proxy that helps measure the condition, based on observations that reflect the dynamics of a particular phenomenon.

- Data, a sufficient amount of qualified observations to reflect the underlying conditions.

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Mapping

4.4. Activity Scoring

- Rank to determine type of direct and indirect indicator. The indicator found in the first rank in a budget code was designated as direct relationship indicator, whereas the indicators in second and third rank were assumed to be indirect. This approach helped in organizing complex judgment and avoid confusion. We limited this level to three possible ranks.

- “The most chosen” rule to determine a direct relationship. If there were multiple indicators ranked by all researchers (for example, indicators 16.1, 14.1, and 11.1 in the first rank for Budget Code 210101), the indicator that most researchers ranked first would be chosen. A similar approach was used to determine the second and third place scores. The indicator chosen by a small number of researchers was ranked second or third only when there was no consensus among the majority of researchers on the placement of an indicator in the second or third place. This approach considered the statistical effects of rates and probabilities that each researcher could consider in his/her decision when classifying the relationship in the previous step.

- Compatibility Score. The compatibility score reflects the overall strength of the relationship between the budget code and specific SDGs. The score shows how well each indicator is supported by the first, second and third ranked of budget codes. We used the following formula to construct the score for each SDG indicator:where X1, X2, and X3 represent the sum of budget codes to which indicator X is assigned in the first, second and third rank, respectively. The weighted score for each rank represents the importance of the direct and indirect relationship; a higher overall score indicates a stronger relationship between SDGs and VF activities. Assigning weighted scores with the aforementioned formula helps treat relationships differently depending on rank order. Note that weighting the first rank more strongly (0.5) than the second and third ranks (each 0.25) and assigning second and third ranks the same weight of 0.25 reflect this study’s intention to explain the relationship into dichotomous categories in order to be in line with the framework of Schultz [52]).(0.5 × X1) + (0.25 × X2) + (0.25 × X3)

4.5. Village Fund Tagging

5. Results

5.1. Village Fund Activities

5.2. Village Fund SDG-Related Activities Scoring

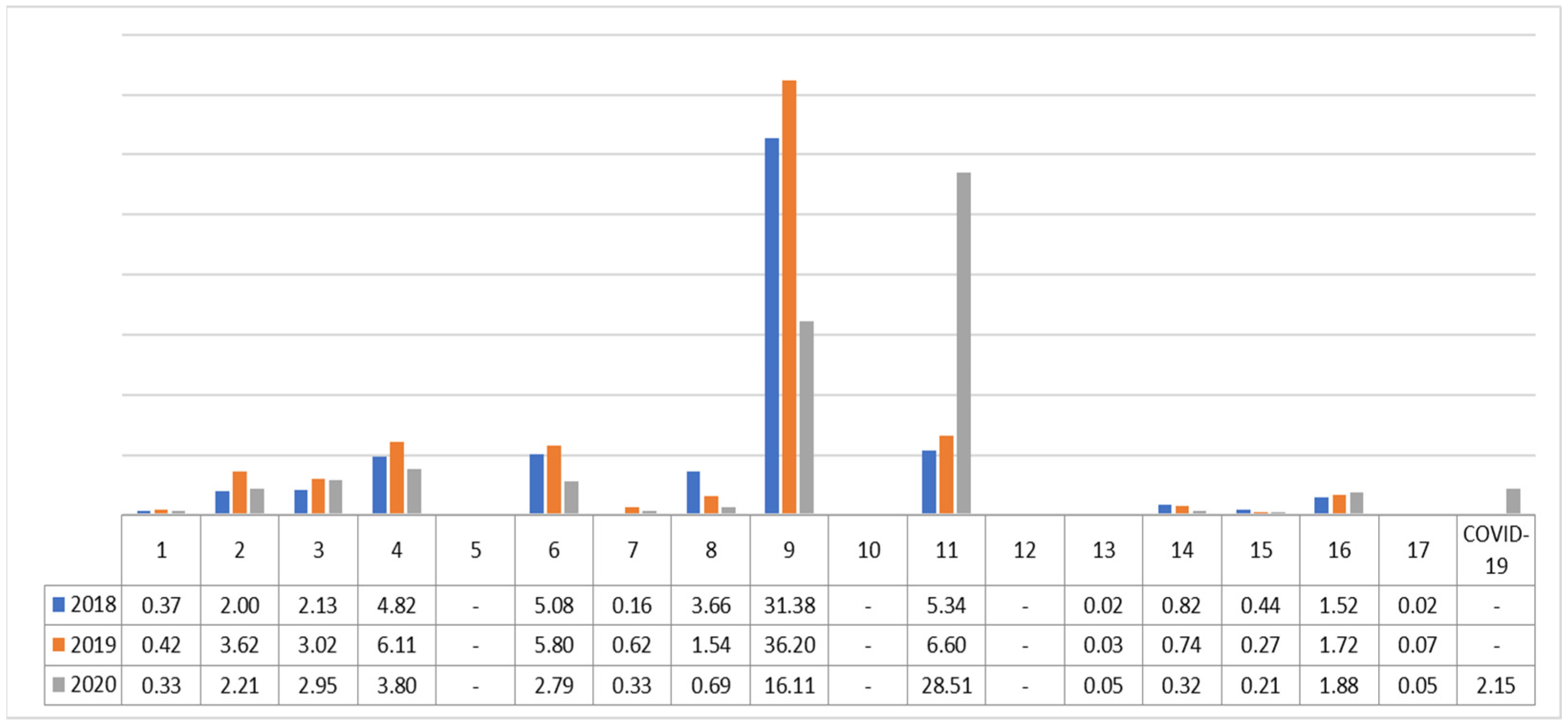

5.3. Village Fund Allocations

6. Discussion

6.1. SDGs with the Highest Allocation

6.2. SDGs with The Lowest Allocation

6.3. Neglected SDG Objectives

6.4. Linkages between the Village Fund and Government Priorities/Existing Regulation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raszkowski, A.; Bartniczak, B. On the Road to Sustainability: Implementation of the 2030 Agenda Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Miguel Ramos, C.; Laurenti, R. Synergies and Trade-offs among Sustainable Development Goals: The Case of Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Rural innovation system: Revitalize the countryside for a sustainable development. J. Rural Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J.; Svobodová, L. How a Participatory Budget Can Support Sustainable Rural Development—Lessons From Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ćurčić, N.; Mirković Svitlica, A.; Brankov, J.; Bjeljac, Ž.; Pavlović, S.; Jandžiković, B. The Role of Rural Tourism in Strengthening the Sustainability of Rural Areas: The Case of Zlakusa Village. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kementerian Keuangan. Buku Saku Dana Desa. 2017. Available online: https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/media/6750/buku-saku-dana-desa.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Rassanjani, S. Indonesian Housing Policy and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Otoritas J. Ilmu Pemerintahan 2018, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Badan Pusat Statistik. Profil Kemiskinan di Indonesia Maret 2021. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/pressrelease/2021/07/15/1843/persentase-penduduk-miskin-maret-2021-turun-menjadi-10-14-persen.html (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Gunawan, J.; Permatasari, P.; Tilt, C. Sustainable development goal disclosures: Do they support responsible consumption and production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 118989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Empowerment Fund (NEF). Rural and Community Development Fund. Available online: https://www.nefcorp.co.za/products-services/rural-community-development-fund/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Smart Growth in Small Towns and Rural Communities. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/smart-growth-small-towns-and-rural-communities#background (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Fiscal Policy Agency. Visi, Misi, Tugas, dan Fungsi. Available online: https://fiskal.kemenkeu.go.id/profil/visi-misi-tugas-fungsi (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Soerjatisnanta, H.; Natamihardja, R. Institutional and Cultural Approaches for Strengthening Human Right Cities and SDG’s at the Village Level. In Proceedings of the 9th World Human Rights Cities Forum, Gwangju, South Korea, 30 September–3 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tempo Program. SDGs Desa Agar Dana Desa Dirasakan Untuk Warga. Available online: https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1404394/program-sdgs-desa-agar-dana-desa-dirasakan-untuk-warga/full&view=ok (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Kementerian Desa. Sosialisasi Permendesa PDTT No 13/20 tentang Prioritas Penggunaan Dana Desa 2021. 2021. Available online: http://www.djpk.kemenkeu.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/sosialisasi-permendesa-13-2020.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Iskandar, A.H. SDGs DESA: Percepatan Pencapaian Tujuan Pembangunan Nasional Berkelanjutan; Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; ISBN 6024339836. [Google Scholar]

- Vulnerable nations lead by example on Sustainable Development Goals research. Nature 2021, 595, 472. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazid, Y.; Abdullah, A.; Mustafa, M. Desa Funds and Achievement of SDG’s Purpose: Normative Study of Sustainable Development in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Islam, Civilization and Science (Isicas 2019), Selangor, Malaysia, 14–15 October 2019; pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Dwitayanti, Y.; Maria; Nurhasanah; Armaini, R. The Impact of Village Fund Program Implementation Toward Society Welfare in Indonesia. In 3rd Forum in Research, Science, and Technology (FIRST 2019); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kadafi, M.; Sudarlan; Sudrahman, H. The implications of village funds received by underdeveloped village per district/city against poverty in Indonesia and literacy rate: Emperical evidence in Indonesia. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 3924–3928. [Google Scholar]

- Arifin, B.; Wicaksono, E.; Tenrini, R.H.; Wardhana, I.W.; Setiawan, H.; Damayanty, S.A.; Solikin, A.; Suhendra, M.; Saputra, A.H.; Ariutama, G.A.; et al. Village fund, village-owned-enterprises, and employment: Evidence from Indonesia. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 79, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Flacke, J.; Martinez, J.; van Maarseveen, M.F.A.M. Participatory planning practice in rural Indonesia: A sustainable development goals-based evaluation. Community Dev. 2020, 51, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonperm, J.; Haughton, J.; Khandker, S.R. Does the Village Fund matter in Thailand? Evaluating the impact on incomes and spending. J. Asian Econ. 2013, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theparat, C. Debt Freeze for Village Fund Tabled. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1582302/debt-freeze-for-village-fund-tabled (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Boonperm, J.; Haughton, J.; Khandker, S.R.; Rukumnuaykit, P. Appraising the Thailand Village Fund; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2012; Volume 5998. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, P.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P.; Sliuzas, R. Spatial analyses of the urban village development process in shenzhen, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 2177–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, K. The WTO Just Ruled against China’s Agricultural Subsidies. Will This Translate to a Big U.S. Win? Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/03/04/wto-just-ruled-against-chinas-agricultural-subsidies-will-this-translate-big-us-win/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Zeng, G.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Sun, H. The Dynamic Impact of Agricultural Fiscal Expenditures and Gross Agricultural Output on Poverty Reduction: A VAR Model Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, J.-L.; Bassole, L. Does Community Driven Development Work? Evidence from Senegal. SSRN Electron. J. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aziz, N.L.L. Otonomi Desa dan Efektivitas Dana Desa. J. Penelit. Polit. 2016, 13, 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Beath, A.; Christia, F.; Enikolopov, R. The National Solidarity Programme: Assessing the Effects of Community-Driven Development in Afghanistan. Int. Peacekeeping 2015, 22, 302–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandoevwit, W.; Ashakul, B. The Impact of the Village Fund on Rural Households. TDRI Q. Rev. 2008, 23, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, R.S.; Sherburne-Benz, L. Household Effects of African Community Initiatives: Evaluating the Impact of the Zambia Social Fund. 2001. Available online: http://www1.worldbank.org/prem/poverty/ie/dime_papers/63.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Deininger, K.; Liu, Y. Longer-Term Economic Impacts of Self-Help Groups in India; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2009; Volume 4886. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, J.; Feuer, H.N.; Kitano, S.; Asahi, H. Assessing the effectiveness of Japan’s community-based direct payment scheme for hilly and mountainous areas. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 160, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonne, J. The KALAHI-CIDSS Impact Evaluation: A Revised Synthesis Report; The World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.S.; Dandona, L.; Hoisington, J.A.; James, S.L.; Hogan, M.C.; Gakidou, E. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: An impact evaluation. Lancet 2010, 375, 2009–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medonos, T.; Ratinger, T.; Hruška, M.; Špička, J. The Assessment of the Effects of Investment Support Measures of the Rural Development Programmes: The Case of the Czech Republic. Agris Online Pap. Econ. Inform. 2012, 4, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve, F.; Zafrilla, J.E.; Cadarso, M.-Á. Where have all the funds gone? Multiregional input-output analysis of the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 129, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J.; Pradhan, M.; Rawlings, L.B.; Ridder, G.; Coa, R.; Evia, J.L. An impact evaluation of education, health, and water supply investments by the Bolivian Social Investment Fund. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2002, 16, 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, M.; Manevska-Tasevska, G. Farm-Level Employment and Direct Payment Support for Grassland Use: A Case of Sweden; Agrifood Economics Centre: Lund, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli, D.; Acharya, G.; Chaudhury, N.; Thapa, B.B. Impact of Social Fund on the Welfare of Rural Households: Evidence from the Nepal Poverty Alleviation Fund; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank: Washington DC, USA, 2012; Volume 6042. [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban, S. Reviewing Egyptian community social fund (village savings and loans association, VSLA) as an approach for community social fund. Hortic. Int. J. 2019, 3, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D. Fundamental Measurement. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1997, 11, 558. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, N.R. Physics: The Elements; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- insight2impact. New Approaches to Measuring Financial Inclusion. Available online: https://cenfri.org/publications/measurement-framework-notes/ (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Finkelstein, L. Widely, strongly and weakly defined measurement. Measurement 2003, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.B. Measurability. Measurement 2007, 40, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stay, J.F. HIPO and integrated program design. IBM Syst. J. 1976, 15, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, W.S. HIPO (hierarchy plus input-process-output). In The Information System Consultant’s Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Subiyakto, A.; Ahlan, A.R. Implementation of Input-Process-Output Model for Measuring Information System Project Success. TELKOMNIKA Indones. J. Electr. Eng. 2014, 12, 5603–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, W.C. On Categorizing Qualitative Data in Content Analysis. Public Opin. Q. 1958, 22, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Basics of Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-205-48.137. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations SDG Indicators: Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017; United Nations: New York, NY, USA,, 2017; Available online: https://undocs.org/A/RES/71/313 (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Burns, T.; Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; The Free Press: Detroit, MI, USA, 1953; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, G. The Future of Coders: Human Judgments in a World of Sophisticated Software. In Text Analysis for the Social Sciences: Methods for Drawing Statistical Inferences from Texts and Transcripts; Roberts, C.W., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 225–238. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, W.C. Reliability, Ambiguity and Content Analysis. Psychol. Rev. 1952, 59, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsueh, P.-Y.; Melville, P.; Sindhwani, V. Data quality from crowdsourcing: A study of annotation selection criteria. In Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2009 Workshop on Active Learning for Natural Language Processing, Boulder, CO, USA, 5 June 2009; pp. 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vuurens, J.; de Vries, A.; Eickhoff, C. How Much Spam Can You Take? An Analysis of Crowdsourcing Results to Increase Accuracy. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGIR Workshop on Crowdsourcing for Information Retrieval, Beijing, China, 28 July 2011; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gatra, S. Jokowi: Infrastruktur dan Dana Desa Kunci Pemerataan. Available online: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2019/04/13/22574631/jokowi-infrastruktur-dan-dana-desa-kunci-pemerataan (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Swaningrum, A. Poverty and Sustainable Community Development in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Integrated Microfinance Management (IMM 2016), Bandung, Indonesia, 19–22 September 2016; pp. 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Odagiri, M.; Cronin, A.A.; Thomas, A.; Kurniawan, M.A.; Zainal, M.; Setiabudi, W.; Gnilo, M.E.; Badloe, C.; Virgiyanti, T.D.; Nurali, I.A.; et al. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals for water and sanitation in Indonesia—Results from a five-year (2013–2017) large-scale effectiveness evaluation. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/UNICEF. Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2017; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sulisworo, D. The Contribution of the Education System Quality to Improve the Nation’s Competitiveness of Indonesia. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishatono, I.; Raharjo, S.T. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) dan Pengentasan Kemiskinan. Share Soc. Work J. 2016, 6, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2020—The Sustainable Development Goals and Covid-19; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Desa. 100 Persen Dana Desa untuk Infrastruktur. Available online: https://kemendesa.go.id/berita/view/detil/1633/100-persen-dana-desa-untuk-infrastruktur (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Nalle, V.I.W.; Syaputri, M.D. Sanitation Regulation in Indonesia: Obstacles and Challenges to the Achievement of SDGs Targets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Sciences in the 21st Century, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 12–14 July 2019; pp. 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank GDP Growth (Annual %)—Indonesia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=ID (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- The Global Economy Indonesia: Unemployment Rate. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Indonesia/unemployment_rate/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Tadjoeddin, M.Z. Decent work: On the quality of employment in Indonesia. Asian J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 42, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmi, H.; Tanjung, N.S.; Figna, L.N.; Silviana, V.P. Adapting in Digital Era of Globalized Agro-food System and Delivery of UN SDGs 1 and 2: Agriculture Extension in Small-scale Red Onion (Shallot) Horticulture Area in Highland Solok District, Indonesia. IPTEK J. Proc. Ser. 2019, 6, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kiryluk-Dryjska, E.; Beba, P.; Poczta, W. Local determinants of the Common Agricultural Policy rural development funds’ distribution in Poland and their spatial implications. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.; Sheil, D.; Galloway, G.; Riggs, R.A.; Mewett, G.; MacDicken, K.G.; Arts, B.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Langston, J.; Edwards, D.P. SDG 15: Life on Land—The Central Role of Forests in Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 482–509. ISBN 9781108765015. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, V.V.; Kubitza, C.; Pascual, U.; Qaim, M. Land markets, Property rights, and Deforestation: Insights from Indonesia. World Dev. 2017, 99, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santika, T.; Meijaard, E.; Budiharta, S.; Law, E.A.; Kusworo, A.; Hutabarat, J.A.; Indrawan, T.P.; Struebig, M.; Raharjo, S.; Huda, I.; et al. Community forest management in Indonesia: Avoided deforestation in the context of anthropogenic and climate complexities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 46, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassanjani, S. Ending Poverty: Factors That Might Influence the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Indonesia. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2018, 8, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sagala, S.; Lubis, W.; Vitri, R.; Rianawati, E.; Nugraha, D.; Ameridiyani, A. Energy Resilient Village Potential in Boyolali, Indonesia; Working Paper Series; Resilience Development Initiative: Bandung, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Gevelt, T.; Canales Holzeis, C.; Fennell, S.; Heap, B.; Holmes, J.; Hurley Depret, M.; Jones, B.; Safdar, M.T. Achieving universal energy access and rural development through smart villages. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 43, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CNN. Indonesia Jokowi Sebut 433 Desa Belum Dapat Aliran Listrik. Available online: https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20200403101725-85-489891/jokowi-sebut-433-desa-belum-dapat-aliran-listrik (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Panjaitan, R.A. Challenges facing the multi-stakeholder partnerships in implementing SDG’s goal: Poverty reduction in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Social and Political Sciences, Jakarta, Indonesia, 14–15 November 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akbar, I. Understanding the Partnership Landscape for Renewable Energy Development in Indonesia. J. Univ. Paramadina 2017, 14, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Quibria, M.G. The global partnership for sustainable development. Nat. Resour. Forum 2015, 39, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tickamyer, A.R.; Kusujiarti, S. Riskscapes of gender, disaster and climate change in Indonesia. Cambridge J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2020, 13, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Supporting Indonesia to Advance their NAP Process. Available online: https://www.adaptation-undp.org/projects/supporting-indonesia-advance-their-nap-process (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Climate Action Tracker Climate Action—Indonesia. Available online: https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/indonesia/ (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Widiastuty, I.L. Peran perempuan dan penduduk terdidik dalam upaya mencapai target sustainable development goals di Indonesia. JPPM (J. Pendidik. Pemberdaya. Masy.) 2018, 5, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report. 2019. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/IDN.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Amri, K.; Nazamuddin, B.S. Is There Causality Relationship Between Economic Growth and Income Inequality? Panel Data Evidence From Indonesia. Eurasian J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldan, B.; Janoušková, S.; Hák, T. How to understand and measure environmental sustainability: Indicators and targets. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Luo, Z.; Wamba, S.F.; Roubaud, D.; Foropon, C. Examining the role of big data and predictive analytics on collaborative performance in context to sustainable consumption and production behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1508–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Wamba, S.F.; Song, M. Towards a theory of sustainable consumption and production: Constructs and measurement. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xia, X.H.; Chen, B.; Sun, L. Public participation in achieving sustainable development goals in China: Evidence from the practice of air pollution control. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiñaga, E.; Henriques, I.; Scheel, C.; Scheel, A. Building resilience: A self-sustainable community approach to the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | RPJMN Goals | SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bringing back the country to protect the people and provide security to all citizens | SDGs 9–10, 13, 16–17 |

| 2 | Establishing clean, efficient, democratic, and reliable governance | SDGs 5, 10, 16–17 |

| 3 | Building from the periphery to strengthen local areas and villages within the framework of a unitary state | SDGs 1–12 |

| 4 | Strengthening the country’s presence in reforming the law enforcement system to be corruption-free, dignified and reliable | SDGs 5, 10, 14–16 |

| 5 | Improving the quality of human life and society | SDGs 1–4, 6, 8, 10 |

| 6 | Improving productivity and competitiveness in the international market | SDGs 8-11, 17 |

| 7 | Realizing economic independence by moving the strategic sectors of the domestic economy | SDGs 2, 6–9, 12–15 |

| 8 | A revolution of national character | SDG 4 |

| 9 | Strengthening diversity and cultural restoration | SDGs 5, 10, 16–17 |

| Goal | SDG Agendas | VF Priorities 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | No Poverty |

|

| 2 | Zero Hunger |

|

| 3 | Good Health and Well-being |

|

| 4 | Quality Education |

|

| 5 | Gender Equality |

|

| 6 | Clean Water and Sanitation |

|

| 7 | Affordable and Clean Energy |

|

| 8 | Decent Work and Economic Growth |

|

| 9 | Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure |

|

| 10 | Reduced Inequalities |

|

| 11 | Sustainable Cities and Communities |

|

| 12 | Responsible Consumption and Production |

|

| 13 | Climate Action | - |

| 14 | Life Below Water | - |

| 15 | Life on Land |

|

| 16 | Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

|

| 17 | Partnership for The Goals | - |

| Authorship | Country/Program | Objects Analyzed | Program Contribution | Method Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arcand and Bassole (2008) [29] | Senegal/Programme National d’Infrastructures Rurales (PNIR) | The impact of the PNIR project in Senegal on access to basic services, household spending, and children’s physical condition. | Improve access and consumption | They used difference-in-difference estimators as well as parallel trend assumptions to test the hypothesis’ evolution over time. |

| Arifin et al. (2020) [21] | Indonesia/Village Fund (VF) | The impact of VF on village-owned enterprises and employment opportunities. | Improve the number of village-owned enterprises | They employed first difference and difference-in-difference, as well as parallel trend hypothesis testing for continuous treatment. |

| Aziz (2016) [30] | Indonesia/Village Fund (VF) | The effectiveness of VF: the achievement of objectives, timeliness, and benefits. | Improve the amount of infrastructure | They conducted analysis data on the amount of Village Funds and realization of Village Funds distributed nationally. |

| Beath et al. (2015) [31] | Afghanistan/National Solidarity Programme (NSP) | The impact of the NSP on democratic processes, access to utilities, and economic welfare. | Improve the amount of infrastructure, but limited quality | They conducted randomized controlled trials across 500 villages to assess the impact. |

| Boonperm et al. (2013) [23] | Thailand/Village and Urban Community Fund (VF) | The impact of VF on incomes and spending. | Unlikely to decrease poverty | They conducted propensity score matching as well as using a fixed-effects/difference model to eliminate selection bias. |

| Chandoevwit and Ashakul (2008) [32] | Thailand/Village and Urban Community Fund (VF) | The impact of VF on household income, expenses, and poverty ratio. | Unlikely to decrease poverty | This study utilized propensity score matching and double difference to assess the impact of the program. |

| Chase and Sherburne-Benz (2001) [33] | Zambia/Zambia Social Fund (ZSF) | The effectiveness of ZSF on poor communities, access to education and health services, and community participation in addressing crucial development issues | Improve access and consumption | The primary source of this study was the Zambia Living Conditions Monitoring Survey with an additional survey module addressing issues on social infrastructure. The other approach was propensity score community matching, pipeline matching and with/without comparisons. |

| Deininger and Liu (2009) [34] | India/Self-Help Groups (SHGs) | The impact of the SHG-based micro-credit model on poor communities, capacity building in larger-scale programs, and equity injection. | Improve access and consumption | This study combined difference-in-difference estimates with propensity score matching. |

| Dwitayanti et al. (2020) [19] | Indonesia/Village Fund (VF) | The impact of VF on the level of community welfare measured by Human Development Index. | Improve the amount of infrastructure and increase community welfare | This study used a simple linear regression analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) program. |

| Ito et al. (2019) [35] | Japan/Direct Payment Scheme (DPS) | The achievement of DPS framework to prevent farmland abandonment in rural areas. | Decrease farmland abandonment | They used propensity score matching to address the non-random community participation in the DPS. Additionally, they used inverse probability weighting and doubly robust estimations to check robustness. They also employed a difference-in-difference approach to improve estimation results of the matching procedure. |

| Kadafi et al. (2020) [20] | Indonesia/Village Fund (VF) | The implication of VF on poverty and literacy rates in underdeveloped villages. | Improve access to education and limited decrease in poverty | In this study, they used a simple linear regression. |

| Labonne (2013) [36] | Philippines/KALAHI-CIDSS | The impact of the program on access to health and education, poverty, and community empowerment/governance. | Improve access and consumption | This study employed qualitative assessment using focus group discussions and comparison analysis of treatment group and control group. Additionally, parallel trend hypothesis and regression were also used. |

| Lim et al. (2010) [37] | India/ Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) | The impact of JSY to reduce the number of maternal and birth-related deaths. | Improve the number of births in health facilities. | They used data from Indian district-level household surveys to evaluate the effect of JSY. For data analysis, they employed exact-matching analysis, with-versus-without analysis, and the difference-in-difference method. |

| Medonos et al. (2012) [38] | Czech Republic/Rural Development Programme (RDP) | Contributions of investment support for Czech agriculture towards business expansion and productivity improvement. | Improve productivity and business expansion | They used propensity score matching in this study to assess the contribution of the investment support for agriculture. |

| Monsalve et al. (2016) [39] | European Union/European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) | The sustainability of EAFRD from a triple bottom line perspective. | Improve economy, slightly increase social performance (depending on the labor categories), and increase negative environmental impact | This study employed standard multiregional input-output (MRIO) model to conduct the analysis. |

| Newman et al. (2002) [40] | Bolivia/Social Investment Fund (SIF) | The impact of small-scale rural infrastructure projects in health, water, and education financed by SIF. | Improve access, but limited quality | They used propensity score matching and observing the differences between treatment groups and comparison groups to assess the impact of the program. |

| Nordin and Manevska-Tasevska (2013) [41] | Sweden/Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) | The influence of CAP, comprising grassland subsidy and direct payments, on farm employment. | Improve employment | This study employed comparative analysis based on a fixed effects model and an instrumental variable model. |

| Parajuli et al. (2012) [42] | Nepal/Poverty Alleviation Fund (PAF) | The impact of PAF on rural household welfare: per capita consumption, food insecurity, school enrollment, and child malnutrition. | Improve access to education and consumption | They conducted two rounds of data surveys and a difference-in-difference method combined with the instrumental variable estimation method. |

| Shaaban (2019) [43] | Egypt/Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA) | The impact of VSLA for women’s economic empowerment and social cohesion. | Improve economy and community participation | This study used case studies in seven regions, with data collection conducted via semi-structured interviews with randomly selected samples. |

| Yazid et al. (2019) [18] | Indonesia/Village Fund (VF) | The impact of VF on supporting economic activities and improving the quality of life of village communities. | Decrease poverty | They used qualitative methods and secondary data collected from archival materials, such as scientific journals and government publications. |

| No | Name (Measurement Unit) | Description | Period | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Village Fund Activities Program (Activity Codes) | The list of all programs activities that can be financed by village funds | 2018, 2019, 2020 | OMSPAN (Treasury and Budget Online Monitoring System), |

| 2 | Sustainable Development Goals Indicators (Indicators) | The list of 231 unique global indicators of the framework for the SDGs | 2020 | United Nations [55] |

| 3 | Village Fund Realization (Measured in IDR) | The realization of village funds by each village in Indonesia, classified by villages, VF activities, and Fiscal Year | 2018, 2019, 2020 | OMSPAN |

| SDG | Description | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Goal 1 | No Poverty |

|

| Goal 2 | Zero Hunger |

|

| Goal 3 | Good Health and Well-being |

|

| Goal 4 | Quality Education |

|

| Goal 5 | Gender Equality |

|

| Goal 6 | Clean Water and Sanitation |

|

| Goal 7 | Affordable and Clean Energy |

|

| Goal 8 | Decent Work and Economic Growth |

|

| Goal 9 | Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure |

|

| Goal 10 | Reduced Inequalities |

|

| Goal 11 | Sustainable Cities and Communities |

|

| Goal 12 | Responsible Consumption and Production |

|

| Goal 13 | Climate Action |

|

| Goal 14 | Life Below Water |

|

| Goal 15 | Life on Land |

|

| Goal 16 | Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions |

|

| Goal 17 | Partnership for The Goals |

|

| SDGs | Main | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 and 2020 | 2018 | 2019 and 2020 | |

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 4.75 | 4.50 |

| 2 | 9 | 8 | 5.75 | 5.00 |

| 3 | 13 | 13 | 13.25 | 13.25 |

| 4 | 44 | 44 | 28.50 | 27.50 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| 6 | 22 | 18 | 16.25 | 13.00 |

| 7 | 3 | 3 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| 8 | 25 | 16 | 16.00 | 11.50 |

| 9 | 42 | 33 | 37.00 | 31.00 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | 0 |

| 11 | 32 | 27 | 22.50 | 19.00 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 3.75 | 3.75 |

| 13 | 2 | 2 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| 14 | 11 | 7 | 7.00 | 5.00 |

| 15 | 10 | 9 | 5.25 | 5.25 |

| 16 | 27 | 27 | 15.25 | 15.25 |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | 2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDGs | IDR | % | SDGs | IDR | % |

| 9 | 31,384,412,923,921 | 54.33% | 9 | 36,201,180,508,977 | 54.24% |

| 11 | 5,340,340,749,691 | 9.24% | 11 | 6,599,482,208,255 | 9.89% |

| 6 | 5,080,924,032,220 | 8.80% | 4 | 6,108,367,243,623 | 9.15% |

| 4 | 4,817,363,906,321 | 8.34% | 6 | 5,799,944,410,121 | 8.69% |

| 8 | 3,658,809,730,389 | 6.33% | 2 | 3,618,742,718,691 | 5.42% |

| 3 | 2,130,551,620,897 | 3.69% | 3 | 3,017,373,458,082 | 4.52% |

| 2 | 1,996,098,399,921 | 3.46% | 16 | 1,717,734,470,167 | 2.57% |

| 16 | 1,520,080,767,426 | 2.63% | 8 | 1,544,220,147,962 | 2.31% |

| 14 | 821,999,106,074 | 1.42% | 14 | 742,414,240,826 | 1.11% |

| 15 | 444,157,836,090 | 0.77% | 7 | 620,569,890,707 | 0.93% |

| 1 | 370,617,622,561 | 0.64% | 1 | 417,308,508,210 | 0.63% |

| 7 | 160,227,575,188 | 0.28% | 15 | 270,109,622,410 | 0.40% |

| 17 | 22,629,260,778 | 0.04% | 17 | 65,532,829,025 | 0.10% |

| 13 | 22,225,284,095 | 0.04% | 13 | 25,559,265,952 | 0.04% |

| 5 | 0 | 0.00% | 5 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 10 | 0 | 0.00% | 10 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 12 | 0 | 0.00% | 12 | 0 | 0.00% |

| SDGs | 2020 (IDR) | 2020 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 28,513,917,628,198 | 45.69% |

| 9 | 16,106,214,685,063 | 25.81% |

| 4 | 3,804,633,956,704 | 6.10% |

| 3 | 2,953,373,790,597 | 4.73% |

| 6 | 2,790,068,342,931 | 4.47% |

| 2 | 2,214,204,702,768 | 3.55% |

| COVID-19 1 | 2,150,742,108,462 | 3.45% |

| 16 | 1,884,848,078,082 | 3.02% |

| 8 | 689,248,464,547 | 1.10% |

| 7 | 329,330,410,759 | 0.53% |

| 1 | 327,073,717,071 | 0.52% |

| 14 | 324,190,881,213 | 0.52% |

| 15 | 212,985,857,179 | 0.34% |

| 13 | 54,955,549,367 | 0.09% |

| 17 | 53,915,592,627 | 0.09% |

| 5 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 10 | 0 | 0.00% |

| 12 | 0 | 0.00% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Permatasari, P.; Ilman, A.S.; Tilt, C.A.; Lestari, D.; Islam, S.; Tenrini, R.H.; Rahman, A.B.; Samosir, A.P.; Wardhana, I.W. The Village Fund Program in Indonesia: Measuring the Effectiveness and Alignment to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112294

Permatasari P, Ilman AS, Tilt CA, Lestari D, Islam S, Tenrini RH, Rahman AB, Samosir AP, Wardhana IW. The Village Fund Program in Indonesia: Measuring the Effectiveness and Alignment to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112294

Chicago/Turabian StylePermatasari, Paulina, Assyifa Szami Ilman, Carol Ann Tilt, Dian Lestari, Saiful Islam, Rita Helbra Tenrini, Arif Budi Rahman, Agunan Paulus Samosir, and Irwanda Wisnu Wardhana. 2021. "The Village Fund Program in Indonesia: Measuring the Effectiveness and Alignment to Sustainable Development Goals" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112294

APA StylePermatasari, P., Ilman, A. S., Tilt, C. A., Lestari, D., Islam, S., Tenrini, R. H., Rahman, A. B., Samosir, A. P., & Wardhana, I. W. (2021). The Village Fund Program in Indonesia: Measuring the Effectiveness and Alignment to Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, 13(21), 12294. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112294