Multi-Stakeholder Impact Environmental Indexes: The Case of NeXt

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Short Review of the Literature

3. A Theoretical Sketch of Our Hypothesis

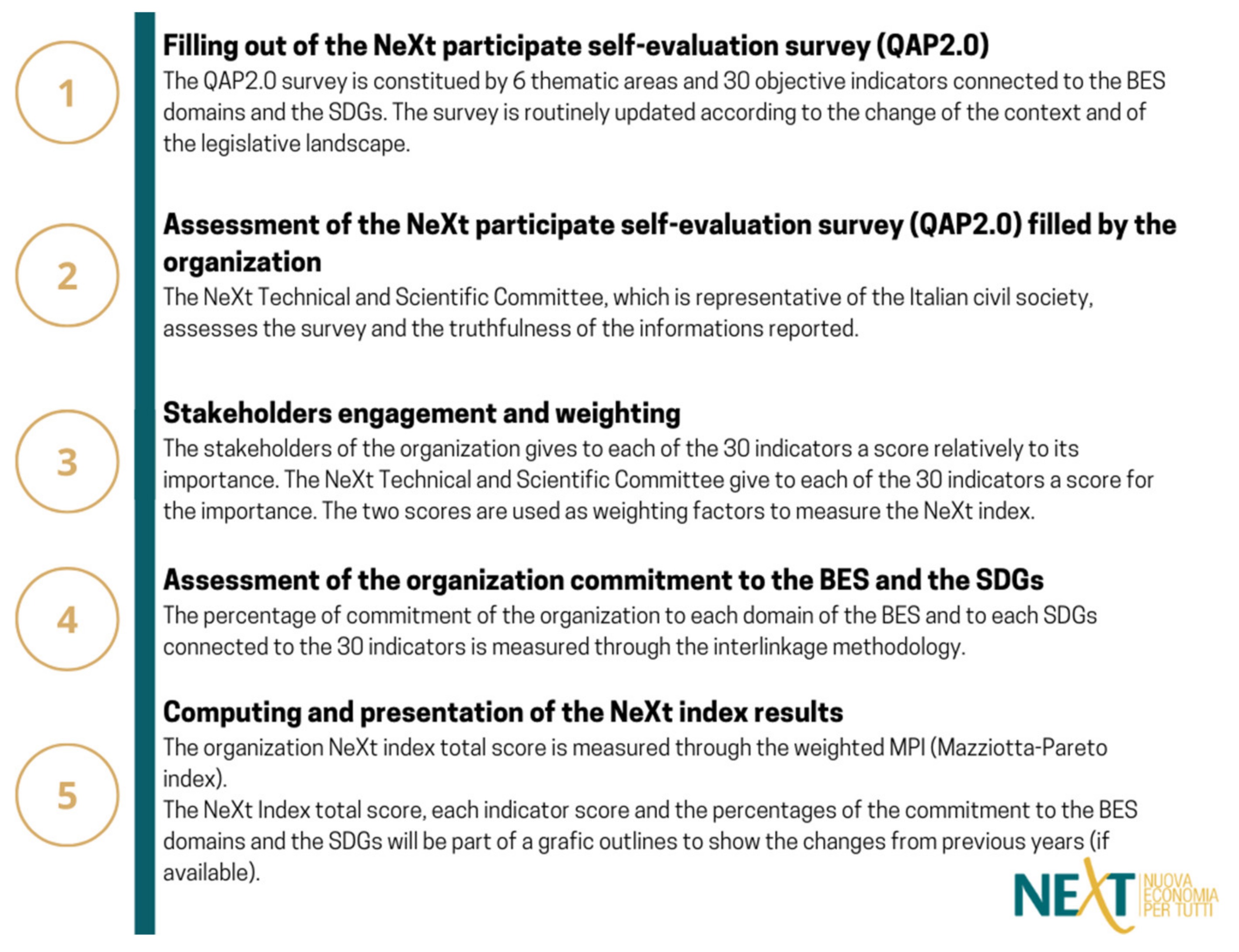

4. The Process for the Construction of the NeXt Index

4.1. Calculus and Ponderation of Individual NeXt Indicators

4.2. Aggregation of NeXt Indicators

4.3. Calculation of NeXt Indicators’ Impacts in Terms of Macroeconomic BES and SDG Domains

- (i)

- An international framework calculating links and the consistency of NeXt indicators with the Sustainable Development Goals of Agenda 2030 (https://unric.org/it/agenda-2030/, accessed on 9 October 2020), issued in 2015 by the United Nations; this implies that each of the 30 NeXt indicators is linked with a reference priority SDG. Such ink made by connecting the survey indicators, the GRI framework indicators (https://www.globalreporting.org/Pages/default.aspx, accessed on 9 October 2020) and the SDGs to each other. The first match was made by the NeXt Study Center, while the SDGs Compass platform (https://sdgcompass.org/, accessed on 9 October 2020) was used for the second match. This platform helps companies implement coherent business strategies with the social and environmental sustainability indicators set by the UN Agenda 2030.

- (ii)

- A national framework calculating links of NeXt indicators with the 12 domains of Benessere Equo e Sostenibile (https://www.istat.it/it/benessere-e-sostenibilit%C3%A0/la-misurazione-del-benessere-(bes)/gli-indicatori-del-bes accessed on 9 October 2020), the Italian multidimentional wellbeing framework designed by Istat [41,42,43], here recalibrated on a corporate basis, becoming BESA, which stands for “fair and sustainable corporate wellbeing” (this implies that each of the 30 NeXt indicators is linked with a reference to a priority BES domain). Link made by connecting the survey indicators, the GRI framework indicators and BES domains to each other. The first match was made by the NeXt Study Center while the BESA theoretical framework was used for the second match.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions: Limits and Direction for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Stakeholders | Stakeholder Type |

|---|---|

| EarthDay Italia, Legambiente, Kyoto Club, | Environmental Ngos |

| Acli, AOI Cooperazione, ARCI, Cittadinanzattiva, CSVNet, CVX, Fondazione Lanza, Forum Nazionale del Terzo Settore, Transparency International, Opera del Murialdo, Fondazione Ebbene | Other Ngos |

| Adige, Fim-CISL, CGIL, CISL, First Social Life, Flaei, UIL, | Trade Unions and/or workers’ associations |

| Adiconsum, Adoc, Federconsumatori, Movimento Consumatori, | Consumers’ association |

| Aipec, Anima, UCID, Fondazione Sodalitas, | Entepreneurs’ associations |

| Altromercato, Banca Etica, Confcooperative, Federcasse, Legacoop, | Cooperative associations and/or social business |

| FairTradeItalia, Impronta Etica, PEFC Italia, | Label and/or certifying and rating companies |

| Istituto Maria Ausiliatrice, Tor Vergata, Unitelma Sapienza, ErsHub, | Education institutions |

| Vita | Media Companies |

Appendix B

| AREAS | INDICATORS | LINK with SDGs and BES |

|---|---|---|

| THE CORPORATE AND ITS GOVERNANC | 1.1. Transparency on shareholders and sources of capital Criterion: transparency on capital ownership with respect to a control group (percentage value). For example: if the main shareholders are X (15%), Y (12%) and Z (8%), the information concerns 35% of the ownership.

|  |

| 1.2. Corporate culture and actions against illegality and corruption Criterion: control of suppliers’ legality and transparency, to be expressed in percentage terms with respect to the controlled suppliers total amount

|  | |

| 1.3. Management strategy and attention to diverse stakeholders Criterion: levels and modes of stakeholders’ engagement, to be expressed through numerical values

|  | |

| 1.4. Employee participation and involvement in corporate strategy decisions Criterion: stakeholders’ engagement in corporate strategy decisions, to be expressed in percentage terms (100% stands for their engagement in every corporate decisions made)

|  | |

| 1.5. Differential between min. and max. remunerations within the company Criterion: differential between the maximum annual remuneration for the best paid and the minimum annual remuneration for the least paid.

|  | |

| PEOPLE AND THE WORKING ENVIRONMEMT | 2.1. Collaborative, participatory and supportive working environment Criterion: job satisfaction share based on work climate surveys, (percent of at least satisfied workers)

|  |

| 2.2. Respect for employee dignity through fair remuneration (concerning work schedule, tasks performed, and responsibilities assigned) Criterion: positive differential between the total amount of remunerations paid by the company and the minimum levels set by the main union contracts (annual basis), to be expressed in percentage terms

|  | |

| 2.3. Dialogue with workers representatives on health and safety at work Criterion: attendance and engagement (of both informative and consultative kind) of one workers’ representative for safety and one workers’ representative for territorial safety

|  | |

| 2.4. Work-Life balance (smart working, gender opportunities, etc.) Criterion: attendance and diversity of work-life balance agreements

|  | |

| 2.5. Employee career development, rewarding employees skills and experience through training and lifelong learning Criterion: for each employee, annual average of training and continuing education hours

|  | |

| RELATIONSHIPS WITH CITIZENS AND CONSUMERS | 3.1. Listening, dialogue and relationships tools with consumers to understand and improve their satisfaction (by facilitating dialogue on both new and traditional media, etc.) Criterion: attendance and diversity of relational tools with clients/consumers

|  |

| 3.2. Full and documented information on the environmental and social sustainability of products/services and all related processes, available to customers Criterion: information on products/service available on labels and informative material

|  | |

| 3.3. Customers’ valorization as a stimulus for partnership innovations and co-design of products/services Criterion: attendance and diversity of interaction modes with clients

|  | |

| 3.4. Effective ways for complaint management and resolution, guaranteeing proper response times and satisfaction levels Criterion: attendance and diversity of complaint management strategies

|  | |

| 3.5. Measurement of customers satisfaction rate (percent of customers at least satisfied customers) Criterion: customer satisfaction rate

|  | |

| THE SUPPLY CHAIN | 4.1. Supply chain transparency Criterion: public visibility of suppliers on the company’s website, to be expressed in percentage terms (percent value share of visible suppliers on total suppliers value)

|  |

| 4.2. Activation of criteria and procedures concerning the choice of direct suppliers and their socio-environmental sustainability Criterion: relationship between sustainable suppliers and all suppliers, to be expressed in percentage terms (avoiding minimum price bid auctions without concern for environmental and social criteria and choices based on cost savings only)

|  | |

| 4.3. Adoption and applications of monitoring tools by suppliers on the socio-environmental sustainability Criterion: monitoring suppliers’ care towards ethics and human rights, through local visits as well as interviews to managers and employees, to be expressed in percentage terms (percent of the value share of monitored suppliers on total suppliers value)

|  | |

| 4.4. Fair and transparent agreements on suppliers’ payments Criterion: late payments with respect to the total amount of payments to suppliers, to be expressed in percentage terms

|  | |

| 4.5. Indirect suppliers’ compliance with sustainability principles for the purchase of raw/processed products Criterion: relationship between the number of materials/tools/products purchased according to sustainability criteria and the total number of materials/tools/products, to be expressed in percentage terms

|  | |

| ATTITUDES/RESPONSABILITY TOWARD THE ENVIRONMENT | 5.1. Climate change mitigation and energy efficiency Criterion: energy efficient deviation from the sectors’ standard greenhouse gases emissions, percent

|  |

| 5.2. Circular economy approach through proper waste management Criterion: efficiency trend about resource use (reduction of landfill waste), percent

|  | |

| 5.3. Energy supply from renewable sources Criterion: energy supply from renewable sources, percent

|  | |

| 5.4. Communication and education initiatives to promote environmental responsibility among citizens Criterion: availability of communication and education initiatives to promote environmental responsibility among citizens, to be expressed in percentage terms (e.g., if the firm provides information for environmental education on 30 products over 100, the answer is 30%)

|  | |

| 5.5. Responsible consumption of natural resources (raw materials, water, soil, etc.) Criterion: two-year reduction trend of raw materials consumed for corporate activities, percent

|  | |

| ATTITUDES/RESPONSABILITY TOWARDS THE LOCAL COMMUNITY | 6.1. Openness and confrontation with local communities on corporate activities and their impact Criterion: worked hours in activities such as meetings on the local heritage, in comparison with the total amount of worked hours, percent

|  |

| 6.2. Constant dialogue and sharing with local stakeholders (institutions, organizations and others) Criterion: average number of meetings with each stakeholder’s category (initiatives and working groups)

|  | |

| 6.3. Participation and support to local development policies, including valorization of local environment and cultural heritage Criterion: reference to projects supporting local development policies, to be expressed in percentage terms in comparison with the corporate profit

|  | |

| 6.4. Promotion and growth of stable work at a local level Criterion: increase in permanent jobs (on a three-year basis), related to locally trained people, percent

|  | |

| 6.5. Mission achievement in collaboration with other companies and local stakeholders Criterion: local outsourcing, supporting local supply chains and non-profit organizations, percent

|  |

Appendix C. The Mazziotta-Pareto Approach to Calculation of the Final Index Score

- (i)

- is the i-th domain score

- (ii)

- is the j-th indicator score

- (iii)

- is the score weight

- (iv)

- is the unweighted arithmetic average of indicators’ scores in the i-th domain

- (v)

- is the weighted average of indicators’ scores in the i-th domain

- (vi)

- is the weighted standard deviation of indicators’ scores in the i-th domain

- (vii)

- is the weighted coefficient of variation in the i-th domain

- (i)

- is the aggregate (NeXt Index) score

- (ii)

- is the i-th domain score

- (iii)

- is the unweighted arithmetic average of domain scores

- (iv)

- is the standard deviation of domain scores

- (v)

- is the coefficient of variation of domain scores.

References

- Settembre-Blundo, D.; González-Sánchez, R.; Medina-Salgado, S.; García-Muiña, F.E. Flexibility and Resilience in Corporate Decision Making: A New Sustainability-Based Risk Management System in Uncertain Times. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2021, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.; Agrawal, D.; Jha, A.; Gastaldi, M.; Paul, S.K.; D’Adamo, I. Addressing the Challenges to Sustainable Initiatives in Value Chain Flexibility: Implications for Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2021, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2019 Green Bond Market Summary. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/2019_annual_highlights-final.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Global Public Procurement Database: Share, Compare, Improve! Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/03/23/global-public-procurement-database-share-compare-improve (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Easterlin, R.A. Does Empirical Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essay in Honor of Moses Abramovitz; David, P.A., Reder, M.W., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commission-report.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Zengin, Y.; Naktiyok, S.; Kaygın, E.; Kavak, O.; Topçuoğlu, E. An Investigation upon Industry 4.0 and Society 5.0 within the Context of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianu, E.; Pîrvu, R.; Axinte, G.; Toma, O.; Cojocaru, A.V.; Murtaza, F. EU Labor Market Inequalities and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.J. Happiness and economic performance. Econ. J. 1997, 107, 1815–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E.; Frijters, P.; Shields, M.A. Relative Income, Happiness, and Utility: An Explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and Other Puzzles. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 95–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being: The Science of Happiness and a Proposal for a National Index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Kahneman, D.; Helliwell, J. International Differences in Well-Being; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P.; White, M.P. How can measures of subjective well-being be used to inform public policy? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, R.; MacCulloch, R. Some uses of happiness data in economics. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 1359–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Tella, R.; MacCulloch, R.J.; Oswald, A.J. Preferences over inflation and unemployment: Evidence from surveys of happiness. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. Happiness, economy and institutions. Econ. J. 2000, 110, 918–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. Beyond outcomes: Measuring procedural utility. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2005, 57, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graham, C. Happiness around the World: The Paradox of Happy Peasants and Miserable Millionaires; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Diener, E.; Schwarz, N. Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B.; Schkade, D.; Schwarz, N.; Stone, A.A. Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science 2006, 312, 1908–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1996; Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2010; Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Revisited: Reflections and Overview; Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. Well-being in nations and well-being of nations. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 91, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becchetti, L.; Corrado, L.; Fiaschetti, M. The regional heterogeneity of wellbeing ‘expenditure’ preferences: Evidence from a simulated allocation choice on the BES indicators. J. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 17, 857–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.R. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Webler, K.; Kastenholz, H.; Renn, O. Public Participation in Impact Assessment: A Social Learning Perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1995, 15, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoux, L.; Chambers, R. Reversing the paradigm: Quantification, participatory methods and pro-poor impact assessment. J. Int. Dev. 2005, 17, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.L.; Campbell, R. Taking Stock of Empowerment Evaluation: An Empirical Review. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J.; Mabee, W.E.; Reed, M.; McAlpine, P. Bottom up and Top down: Analysis of Participatory Processes for Sustainability Indicator Identification as a Pathway to Community Empowerment and Sustainable Environmental Management. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 78, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social Impact Assessment: The State of the Art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthen, M.; Veale, A.; McKay, S.; Wessells, M. The Transformative and Emancipatory Potential of Participatory Evaluation: Reflections from a Participatory Action Research Study with War-Affected Young Mothers. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2019, 47, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation; Sage: Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, R.G. Collaborative Evaluation within a Framework of Stakeholder-Oriented Evaluation Approaches. Eval. Program Plann. 2012, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Learning from experience in sustainability. In Proceedings of the International Sustainable Development Research Conference 2003, Nothingham, UK, 24–25 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Björkman, M.; Svensson, J. When is community-based monitoring effective? evidence from a randomized experiment in primary health in Uganda. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 8, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbio, L.; Pomatto, G. Il coinvolgimento dei cittadini nelle scelte pubbliche. Nuove Forme Di Democrazia 2007, 58, 1000–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta, M.; Pareto, A. Measuring Well-Being Over Time: The Adjusted Mazziotta–Pareto Index Versus Other Non-compensatory Indices. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 136, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istat. Rapporto SDGs 2019. Informazioni Statistiche per l’Agenda 2030 in Italia. 2019. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/04/SDGs_2019.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Istat. BES 2019. Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2019/12/Bes_2019.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Istat. Appendice Statistica al Rapporto. BES 2019, Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/236714 (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- A Sense of Purpose. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2018/01/17/a-sense-of-purpose/ (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Laufer, W.S. Social accountability and corporate greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2011, 20, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Becchetti, L.; Cacciapaglia, M.; Morone, P.; Raffaele, L.; Semplici, L. Multi-Stakeholder Impact Environmental Indexes: The Case of NeXt. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212364

Becchetti L, Cacciapaglia M, Morone P, Raffaele L, Semplici L. Multi-Stakeholder Impact Environmental Indexes: The Case of NeXt. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212364

Chicago/Turabian StyleBecchetti, Leonardo, Maristella Cacciapaglia, Piergiuseppe Morone, Luca Raffaele, and Lorenzo Semplici. 2021. "Multi-Stakeholder Impact Environmental Indexes: The Case of NeXt" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212364

APA StyleBecchetti, L., Cacciapaglia, M., Morone, P., Raffaele, L., & Semplici, L. (2021). Multi-Stakeholder Impact Environmental Indexes: The Case of NeXt. Sustainability, 13(22), 12364. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212364