Supply Chains’ Failure in Workers’ Rights with Regards to the SDG Compass: A Doughnut Theory Perspective

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation for Study

2.2. Problem Statement

- How do the UN SDGs map onto the social foundations of the doughnut model, with respect to workers’ rights in supply chains?

- With each element of the social foundations of the doughnut model, what issues arise concerning the violations of workers’ rights in supply chains?

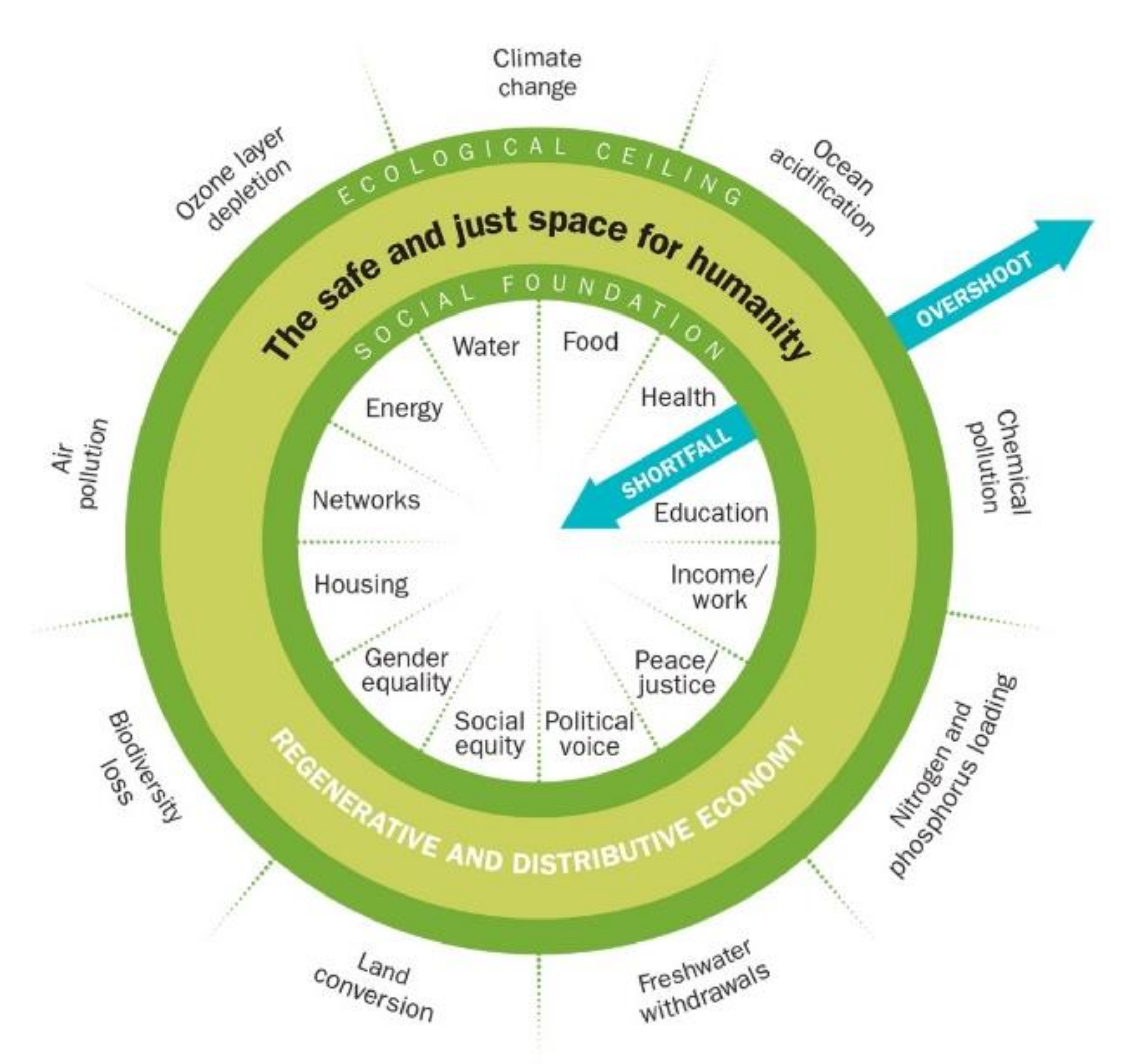

3. Doughnut Theory

4. SDGs through a Doughnut Theory Lens

5. Exploring Workers’ Rights in Supply Chains with Regards to SDGs with Doughnut Theory Lens

5.1. Basic Needs (Water, Food, Housing, Energy)

5.1.1. Key Issues

5.1.2. Examples

5.2. Health

5.2.1. Key Issues

5.2.2. Examples

5.3. Education

5.3.1. Key Issues

5.3.2. Examples

5.4. Work and Income

5.4.1. Key Issues

5.4.2. Example

5.5. Peace and Justice

5.5.1. Government

Key Issues

Examples

5.5.2. NGOs

Key Issues

Examples

5.5.3. International Labour Organization (ILO) and World Trade Organization (WTO)

Key Issues

Examples

5.5.4. Unions

Key Issues

Examples

5.6. Social Equality

5.6.1. Key Issues

5.6.2. Examples

5.7. Gender Equality

5.7.1. Key Issues

5.7.2. Examples

5.8. Networks

5.8.1. Key Issues

5.8.2. Examples

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Contribution to Theory

6.2. Contribution to Practice

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pagell, M.; Shevchenko, A. Why research in sustainable supply chain management should have no future. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2014, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautrims, A.; Schleper, M.C.; Cakir, M.S.; Gold, S. Survival at the expense of the weakest? Managing modern slavery risks in supply chains during COVID-19. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, Government Continued to Source PPE from Malaysia Suppliers Accused of Modern Slavery, the Independent. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/covid-ppe-gloves-malaysia-nhs-government-latest-b1812320.html (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Miller, F.A.; Young, S.B.; Dobrow, M.; Shojania, K.G. Vulnerability of the medical product supply chain: The wake-up call of COVID-19. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2021, 30, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Eusanio, M.; Zamagni, A.; Petti, L. Social sustainability and supply chain management: Methods and tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, F.A.; Chowdhury, I.N.; Klassen, R.D. Social management capabilities of multinational buying firms and their emerging market suppliers: An exploratory study of the clothing industry. J. Oper. Manag. 2016, 46, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Croom, S.; Vidal, N.; Sceptic, W.; Marshall, D.; McCarthy, L. Impact of social sustainability orientation and supply chain practices on operational performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 2344–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamba, C.C.; Chan, P.W.; Sharmina, M. How does social sustainability feature in studies of supply chain management? A review and research agenda. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 522–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S.; Tang, C.S. Corporate social sustainability in supply chains: A thematic analysis of the literature. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 882–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Mubarik, M.S.; Kusi-Szarpong, S.; Zaman, S.I.; Alam Kazmi, S.H. Social sustainable supply chains in the food industry: A perspective of an emerging economy. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.; McCarthy, L.; McGarth, P.; Claudy, M.C. Going above and beyond: How sustainability culture and entrepreneurial orientation drive social sustainability supply chain practice adoption. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Schleper, M.C.; Blome, C. Conflict minerals and supply chain due diligence: An exploratory study of multi-tier supply chains. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. World Employment Social Outlook. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_615594.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Ange Aboa, A.R. Child Labour Rising in West Africa Cocoa Farms Despite Efforts: REUTERS. 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-cocoa-childlabour-ivorycoast-ghana-idUKKBN2742FU (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Doward, J. Children as Young as Eight Picked Coffee Beans on Farms Supplying Starbucks. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/mar/01/children-work-for-pittance-to-pick-coffee-beans-used-by-starbucks-and-nespresso (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Bird, R.C.; Soundararajan, V. From suspicion to sustainability in global supply chains. Tex. AML Rev. 2019, 7, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egels-Zandén, N.; Lindholm, H. Do codes of conduct improve worker rights in supply chains? A study of Fair Wear Foundation. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anner, M. Monitoring workers’ rights: The limits of voluntary social compliance initiatives in labor repressive regimes. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleper, M.C.; Stanczyk, A.; Blome, C. Archetypes of Global Sourcing Decision-Making: The Influence of Contextual Factors. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management 2018, Chicago, IL, USA, 10–14 August 2018; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018; p. 10510. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, D.; Greenleaf, A.R.; Lake, M.; Levi, M.; Noveck, J. Governing global supply chains: What we know (and don’t) about improving labor rights and working conditions. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A.; Delgado, C. Supply chain social sustainability: Standard adoption practices in Portuguese manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 198, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Breuer, A.; Janetschek, H.; Malerba, D. Translating sustainable development goal (SDG) interdependencies into policy advice. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niestroy, I. How Are We Getting Ready? The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in the EU and Its Member States: Analysis and Action so Far; Discussion Paper; German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE): Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nakicenovic, N.; Messner, D.; Zimm, C.; Clarke, G.; Rockstrom, J.; Aguiar, A.P.; Boza-Kiss, B.; Campagnolo, L.; Chabay, L.; Collste, D.; et al. TWI2050-The World in 2050 (2019). The Digital Revolution and Sustainable Development: Opportunities and Challenges; The World in 2050 Initiative; International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA): Laxenburg, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, B. Modern Slavery is an Enabling Condition of Global Neoliberal Capitalism: Commentary on Modern Slavery in Business; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rippingale, J. Consumers are Not Aware We Are Slaves inside the Greenhouses. 2019. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2019/10/16/consumers-are-not-aware-we-are-slaves-inside-the-greenhouses (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Erneut 81 Corona-Fälle in Tönnies-Schlachthof, in Zeit Online. 2020. Available online: https://www.zeit.de/zustimmung?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.zeit.de%2Fgesellschaft%2Fzeitgeschehen%2F2020-10%2Ftoennies-fleischindustrie-coronavirus-soegel-ausbruch-schlachthof (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Arnold, M. Abattoir Coronavirus Outbreak Triggers Infections Surge in Germany, in FT. 2020. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/057e861b-ef35-418d-9d16-81d2a0219212 (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- NGG. Für die Fleischkonzerne Heiligt der Profit alle Mittel. Das Arbeitsschutzkontrollgesetz Muss eins zu eins Umgesetzt Werden. 2020. Available online: https://www.ngg.net/presse/pressemitteilungen/2020/fuer-die-fleischkonzerne-heiligt-der-profit-alle-mittel-das-arbeitsschutzkontrollgesetz-muss-eins-zu-eins-umgesetzt-werden/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Nordrhein-Westfalen, Alle Gegen Tönnies, in Süddeutsche Zeitung. 2020. Available online: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/nordrhein-westfalen-alle-gegen-toennies-1.4946220 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Connolly, K. Meat Plant Must be Held to Account for COVID-19 Outbreak, Says German Minister. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/22/meat-plant-must-be-held-to-account-covid-19-outbreak-germany (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Germany: Coronavirus Exposes Meat Workers’ Plight, in DW. 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/germany-coronavirus-exposes-meat-workers-plight/a-53902174 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Oltermann, P. German Police Raid Meat-Processing Firms Suspected of Smuggling Workers, in Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/german-police-raid-meat-industry-firms-over-illegal-workers/a-55022253 (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Klassen, R.D.; Vereecke, A. Social issues in supply chains: Capabilities link responsibility, risk (opportunity), and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghababsheh, M.; Gallear, D. Socially sustainable supply chain management and suppliers’ social performance: The role of social capital. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 173, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. The Rana Plaza Accident and Its Aftermath. 2018. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/geip/WCMS_614394/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Davies, R.; Kelly, A. More than £1bn Wiped Off Boohoo Value as It Investigates Leicester Factory, in Gaurdian. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/jul/06/boohoo-leicester-factory-conditions-covid-19 (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Sanders, L. Leicester Lockdown Unveils the Truth about Its Fast Fashion Industry, in Euronews. 2020. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/culture/2020/07/12/leicester-lockdown-unveils-the-truth-about-its-fast-fashion-industry (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Miklós, A. Exploiting injustice in mutually beneficial market exchange: The case of sweatshop labor. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybarczyk, K. Ending Child Labor in Mica Mines in India and Madagascar. 2021. Available online: https://stopchildlabor.org/ending-child-labor-in-mica-mines-in-india-and-madagascar/ (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Bernacchio, C. Virtue beyond contract: A MacIntyrean approach to employee rights. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A. SLAVE LABOUR Your Groceries Picked by Slaves—How Britain’s Biggest Slavery Gang Supplied Supermarkets such as Tesco, Asda and M&S, in Sun. 2019. Available online: https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/9454633/your-groceries-picked-by-slaves-how-britains-biggest-slavery-gang-supplied-supermarkets-such-as-tesco-asda-and-ms/ (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Dawkins, C.E. A normative argument for independent voice and labor unions. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 1153–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Ortega, O.; Outhwaite, O.; Rook, W. Buying power and human rights in the supply chain: Legal options for socially responsible public procurement of electronic goods. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2015, 19, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gualandris, J.; Klassen, R.; Vachon, S.; Kalchsmidt, M.G.M. Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mares, R. The limits of supply chain responsibility: A critical analysis of corporate responsibility instruments. Nord. J. Int. Law 2010, 79, 193–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelly, A. Primark and Matalan among Retailers Allegedly Cancelling £2.4bn Orders in ‘Catastrophic’ Move for Bangladesh, in Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/02/fashion-brands-cancellations-of-24bn-orders-catastrophic-for-bangladesh (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Mosley, L. Workers’ rights in global value chains: Possibilities for protection and for peril. New Political Econ. 2017, 22, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, T. Building a sustainable supply chain: An analysis of corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices in the Chinese textile and apparel industry. J. Text. Inst. 2011, 102, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfaty, G.A. Shining light on global supply chains. Harv. Int. J. 2015, 56, 419. [Google Scholar]

- Feinmann, J. The scandal of modern slavery in the trade of masks and gloves. BMJ 2020, 369, m1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, R.M. The Promise and Limits of Private Power: Promoting Labor Standards in a Global Economy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K. When subterranean slavery supports sustainability transitions? power, patriarchy, and child labor in artisanal Congolese cobalt mining. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, K.; Tyler, M. Sexual Harassment, Sexual Violence and CSR: Radical Feminist Theory and a Human Rights Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundy, A. How to Make Business Fix Supply Chain Flaws, in FT. 2020. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/8f03f397-d36f-467c-8907-98beb5ce9e9c (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Boström, M.; Pati, R.K.; Padhi, S.; Govindan, K. Sustainable and responsible supply chain governance: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. Horizontal Collaboration in Response to Modern Slavery Legislation: An Action Research Project Peyton, N. West African Countries on Alert for Child Labor Spike Due to Coronavirus. 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-westafrica-traffic-idUSKBN22C2KI (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Rajeev, A.; Pati, R.K.; Padhi, S.; Govindan, K. Evolution of sustainability in supply chain management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, R. The UN Framework on Business and Human Rights: A workers’ rights critique. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketokivi, M.; Choi, T. Renaissance of case research as a scientific method. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section below in the Paper | Doughnut Theory Social Foundation Elements | Social Focused SDGs |

|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | Basic needs: water, food, energy, housing |   |

| 5.2 | Health |  |

| 5.3 | Education |  |

| 5.4 | Income and work |  |

| 5.5 | Peace and justice |  |

| 5.6 | Social equality |  |

| 5.7 | Gender equality |  |

| 5.8 | Networks |  |

| Environmentally focused SDGs (not the focus of this research) |       | |

| Those SDGs related to the ideal layer |   | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lotfi, M.; Walker, H.; Rendon-Sanchez, J. Supply Chains’ Failure in Workers’ Rights with Regards to the SDG Compass: A Doughnut Theory Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212526

Lotfi M, Walker H, Rendon-Sanchez J. Supply Chains’ Failure in Workers’ Rights with Regards to the SDG Compass: A Doughnut Theory Perspective. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212526

Chicago/Turabian StyleLotfi, Maryam, Helen Walker, and Juan Rendon-Sanchez. 2021. "Supply Chains’ Failure in Workers’ Rights with Regards to the SDG Compass: A Doughnut Theory Perspective" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212526

APA StyleLotfi, M., Walker, H., & Rendon-Sanchez, J. (2021). Supply Chains’ Failure in Workers’ Rights with Regards to the SDG Compass: A Doughnut Theory Perspective. Sustainability, 13(22), 12526. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212526