Access and Benefit Sharing and the Sustainable Trade of Biodiversity in Myanmar: The Case of Thanakha

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Access and Benefit Sharing, and the Use of Natural Ingredients

- -

- Access to GR and TK is granted through a “prior informed consent (PIC)” given by the national authority of a provider country to a user.

- -

- The sharing of the benefits derived from the use of GR and associated TK must be agreed upon according to some conditions between the providers and users, through the so-called “mutually agreed terms” (MAT) [5].

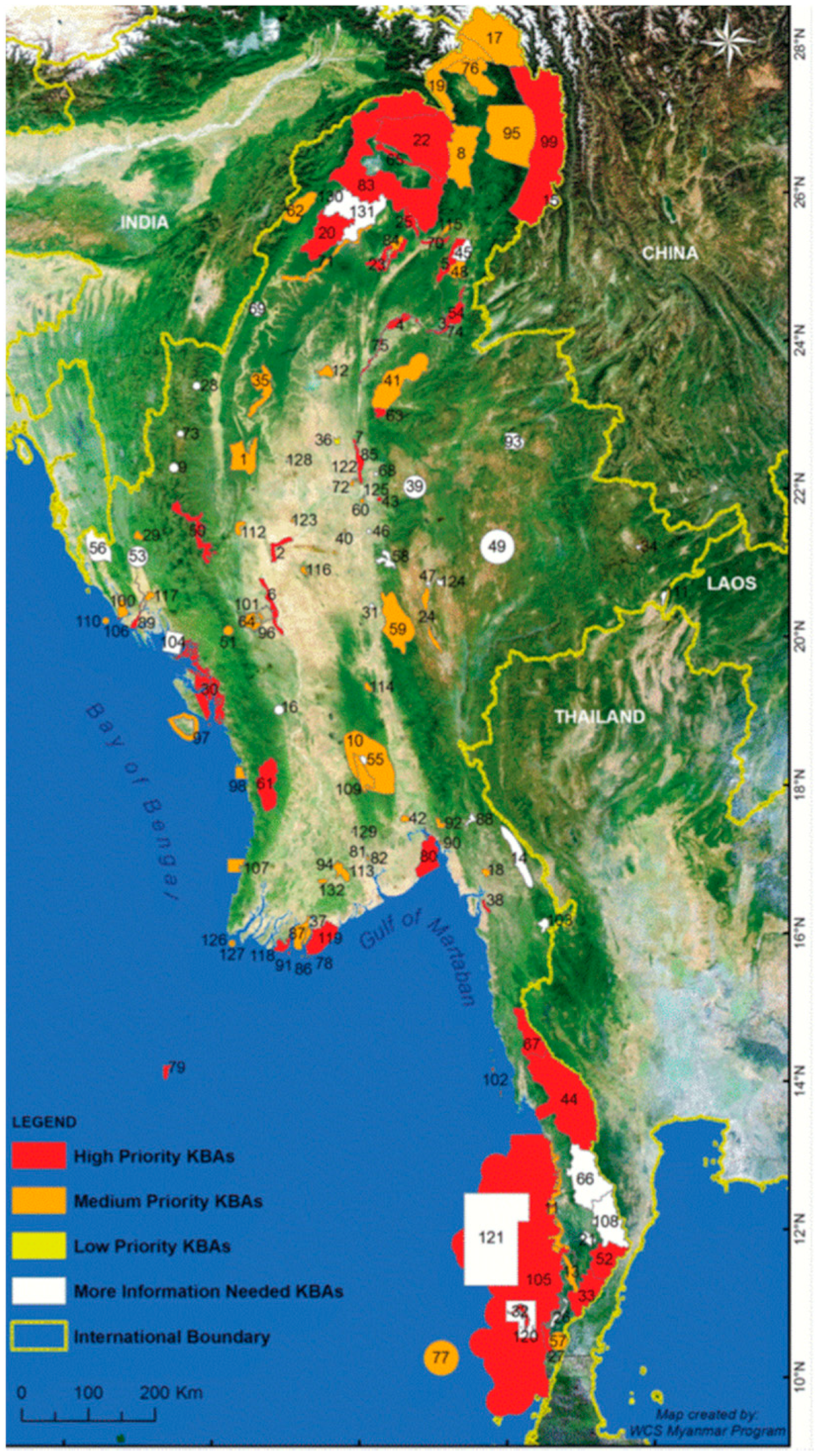

1.2. Biodiversity in Myanmar

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Situation of Access and Benefit Sharing in Myanmar

3.1.1. Institutional Framework for Biodiversity and ABS Matters in Myanmar

3.1.2. Regulatory Framework and Current Developments Related to ABS

3.1.3. Current Changes Happening in the Legislation Related to ABS

3.1.4. Recent and Current ABS Supporting Activities in Myanmar

3.1.5. ABS Institutional and Policy Framework

3.1.6. Current Situation on Traditional Knowledge (TK) in Myanmar

3.1.7. Possible Options Identified by the Interviewed Stakeholders

3.1.8. Overview of the Obstacles and Limitations Identified

3.1.9. Limited Awareness of the Value of GR and Understanding about an ABS System

3.2. Thanakha and Access and Benefit Sharing in Myanmar

3.2.1. Thanakha in Myanmar

3.2.2. Thanakha Value Chain in a Nutshell and Its Involved Actors

- a.

- Value Chain Actors

- Farmers: Thanakha farmers are at the core of the Thanakha value chain for the production of the raw material, managing the local resources and owning the Myanmar thanakha-related traditions and culture.

- Intermediaries: Thanakha brokers and traders operate at different levels. At the local level, intermediaries source directly from the farmers, transport the goods, and sell to local processing plants and the regional wholesaler in the Pakokku township. At the national level, traders distribute raw Thanakha to the retailers and processors across the whole country. An important number of local traders are also farmers, producing and selling directly to consumers at local markets. The sales are mainly performed in traditional formats of different cut-stem styles. An important regional Thanakha market is located in Myaing town, where customers from the township can buy locally produced Thanakha. Another important Thanakha market is located in Ayardaw town. The sale prices can vary depending mostly on the quality, but for a cut of stem of medium quality the price rounds out to 1500 MMK (USD 1). While the sourcing practices of these actors are mostly directly from farmers, the direction of the trader´s sales varies between local processors, regional wholesalers, and national processors. This group creates the most extended net of actors across the country, connecting farmers with processors, other intermediaries, manufacturers, retailers and finally customers. Unlike other Thanakha actors, the intermediaries are mainly women (Figure 8).

- Thanakha processors: Thanakha processors are commonly family-based small- to medium-sized companies located at the local or regional level. The business is based on transforming raw Thanakha into paste bars by grinding Thanakha branches using a wheel shaped “Taung Oo” stone that spins, driven by an engine-powered machine. Another business associated with local processing plants consists of peeling the bark from the stems to supply the manufacturing industry. The whole Thanakha paste production process consists on seven steps; first is the grinding of the Thanakha branches in the machine using water to obtaining, as a result, a muddy solution of water and Thanakha. Then comes the filtering process, leaving the solution on a filter-based structure for around 6 h; the complete draining of the water is done using a press system for approximately one hour, followed by a manual molding process once the paste is obtained, to finally pass through a sun- drying stage before the packaging of the final Thanakha paste bars. While local processors source most of their raw material from local traders, regional processors source mostly from regional wholesalers that distribute to almost the whole country. Both local and regional processors sell their final products directly to local and national retailers, although partly for demand-based cases, sales are also made directly to consumer.

- Thanakha manufacturers: Among the most important Thanakha value chain actors for value adding and the market value share are the manufacturers of Thanakha-based modern cosmetics. Mainly located in Yangon, these family-based businesses are currently an important driving force for the Thanakha industry, and are also involved in the expansion of the sector to other countries through export activities. Two major manufacturing companies currently operating in Myanmar are Shwe Pyi Nann, the largest Thanakha company in Myanmar, owning 125 acres of Thanakha plantation in Bagan, and Shwe Bo Minthamee, which has been involved in the Thanakha business sector since 1971. Although the business focus is still on manufacturing traditional Thanakha paste, they are also putting in efforts to develop Thanakha-based cosmetics and a variety of other skin care products. Both companies are currently exporting their products to Thailand, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Australia, Germany, and the USA. These companies do not source directly from farmers, but from a regional wholesaler from Pakokku Township and either local or regional processors supplying Thanakha bark.

- b.

- Enabling environment

- Thanakha farmers’ and traders’ associations: Thanakha farmers’ and traders’ associations are an important element within the Thanakha Market System in Myanmar, as they represent the Thanakha farmers from the main productive areas at the township level. The associations from the Ayardaw (300 members) and Yesagyo (508 members) Townships were created in 2014, followed by the Myaing Township association (380 members) in 2015. The Pakokku Township association is in the process of being formalised. The associations’ role is to support the development of new markets, to increase the Thanakha surface area by attracting more farmers to Thanakha production activities, and to support Thanakha farmers financially and with technical and marketing skills.

- Thanakha business associations: Two main associations in the Thanakha business sector exist. Both associations pursue the further development of the Thanakha industry in Myanmar. Its main role is to promote market expansion and encourage the export of Thanakha-based modern cosmetics. The Thanakha National Federation involves farmers and traders through their respective associations, and three large manufacturing companies. The main role of the Thanakha National Federation is to facilitate a dialogue platform for the Thanakha value chain actors to discuss constraints from production to marketing.

- Government ministries and agencies: While the role of the state in the sustainable development of the Thanakha industry is crucial, currently, the promotion of the Thanakha sector is not one of Myanmar’s government priorities. In any case, there are some initiatives driven by specific ministries promoting the development of Myanmar’s Thanakha industry. Thanakha is categorized as a NTFP by the Forest Department, which issues permits for the transport of these resources, but farmers still claim to have problems in transporting unprocessed Thanakha. The Ministry of Commerce has facilitated the creation of the Thanakha Farmers’ and Traders’ Associations at the township level, and is supporting Thanakha-business-related companies with foreign R&D institutions.

- International organizations: Even if they are not closely related to the Thanakha Value Chain in Myanmar, there still is a group of international organizations supporting the sustainable development of biodiversity-based products in the region. UNCTAD is supporting Thanakha VC through the Regional BioTrade Project. GEF, UNDP, UNEP and ACB have been supporting the implementation of the Nagoya Protocol in the region, as well as the protection of traditional national products like Thanakha.

- Research institutes: Yezin Agricultural University and Yadanabon University in Mandalay are currently performing research on Thanakha, specifically on Thanakha paste’s properties and its shelf-life, and about the traditional cultural aspects of Thanakha. Further studies are needed on the various properties of Thanakha in order to reveal its skin therapeutic potential [31].

3.2.3. Thanakha’s Commercialization and Export Potential

3.2.4. Thanakha’s Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge

3.2.5. Potential Equitable Benefit Sharing in the Thanakha Sector

4. Implications for the Implementation of ABS Measures for the Thanakha Sector

- (i)

- Collect and consolidate available information regarding Thanakha TK

- (ii)

- Document verbal traditional knowledge through guidelines devel-oped together with the local community and recognized by the government

- (iii)

- Develop benefit sharing agreements with the identified and recognized TK owners.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- LAWS Year

- Environmental Conservation Law and subsidiary legislation 2012

- Environmental Conservation Law 2012

- Seed Law 2011

- Myanmar Constitution 2008

- Conservation of Water Resources and Rivers Law 2006

- Traditional Medicine Law 1996

- Protection of Wildlife and Conservation of Natural Areas Law 1994

- Marine Fisheries Law 1993

- Forest Law 1992

- Freshwater Fisheries Law 1991

- POLICY

- National Sustainable Development Strategy 2009

- National Forestry Sector Master Plan 2000

- Myanmar Agenda 21 1997

- Forest Policy 1995

- National Environmental Policy 1994

- MoALI Agricultural Research Department (ARD): the MoALI ARD applies the Standard Material Transfer Agreement (SMTA) under the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (ITPGRFA) for the transfer of GRs from the seed bank to be shared with local and international organizations for research and propagation purposes (pers. comm MoALI-ARD Seed Bank). The collector does not share any benefits than those indicated in the SMTA. This point was identified as a constraint as stated in UNEP-China Trust Fund Project Final Report, as the level of benefits that can be achieved according to the SMTA under the ITPGRFA are limited [40]. Furthermore, to strengthen public awareness and participation in conserving plant genetic resources, the National Information Sharing Mechanism on the Implementation of Global Plan of Action for the Conservation and Sustainable Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture [57], has been developed. The MoALI is also starting to work on plant variety protection (PVP) system for traditional varieties (pers. comm MoALI-ARD Seed Bank). A good example mentioned was the case of the Dutch company Rijkzwaan, which wanted to collect good genes of Kasseti cucumber variety (small melon) to be introduced in the melon varieties produced in Europe. Rijkzwaan is in the process to prepare an MoU with MoALI ARD to collect this variety. However, since the kasseti is a weed and it is not cultivated, it is impossible to sign an MoU to transfer this species, which is also not in the list ITPGRFA list. In this case, an ABS system would be appropriate. So, there were exchanges between the MoALI-ARD and the MoNREC-ECD. Yet, the MoNREC-ECD has not started to work on SMTA, and the Dutch company refuses to collect any species without the SMTA.

- MoNREC -Forest Research Institute, Forest Department (FRI): According to pers. comm. with the MoNREC Forest Research Institute, the FRI deals mostly with individuals and the system of permission that they give to access to forest GR from the World Heritage Sites is through institutional arrangements on a case by case basis. They expressed the need to do more systematic inventory of Myanmar’s forest resources and they have existing arrangements on how this can be done. They conduct research on forest genetic resources in 68 districts, sustainable use of genetic resources, significant landscape conservation. They collect ethnobotany information on TK (on the use of GR and wildlife). They partnered with Japanese research institutes for an inventory of flora of Myanmar. The new Local community forest allows the allocation of land for forest community. Forest communities need to manage the land in a sustainable way. After a few years, communities can collect some of their forest GR and sell them within their township. Selling outside their township area, would imply the payment of a percentage on their sold produce to the local government.

- MoH, Department of Traditional Medicine (DTM): DTM works with about 3000 national companies involved in production and trading of TM (Fame Pharmaceuticals, Yokepyo Pharmaceutical company, Lwin Win Myint Aung & U Tha Yin Industries, Great Wall and Mawriya companies). Recent small collaboration with foreign institutes, like Miyazaki University and Toyama University of Japan have started to conduct joint research and capacity building. Through this MoU, the Japanese universities can collect medicinal plants and breed them in their labs. The DTM organizes the botanists who could accompany the Japanese researchers to Thanindary and Kahin State, looking for specific wild medicinal plants, through the contact with community’s leaders, TM practitioners, and TM local authorities at state/province/township level. The collection of the medicinal plants is done for academic purpose. The Japanese research institute, on the other hand, grants training (Study tours for a number of Myanmar officers from DTM) in their universities on good manufacture practice of TM, and quality control, as well it informs on research findings, and offers co-authorship of research papers. Another Japanese institute, the Nakayama University, signed a collaboration agreement in 2017 with DTM for chemical analysis of natural compounds. The DTM does not apply any PIC, or MAT, or MTA. According to pers. comm. from DTM, they do not own much knowledge about ABS at DTM, but the department was invited to present the overview of the Myanmar ABS system in a conference in Thailand held in June 2018.

- MoE—Biotechnology Research Department (BRD): According to current staff at BRD, it was reported a limited knowledge and involvement in ABS related issues. BRD work involves research on plant and animal GRs in Myanmar. They stipulate MoU, with the International Foundation for Research grant, which provides the material for research and training and use of labs in Manitoba in return. The previous director who was involved in the UNEP-China trust fund project and the UNDP GEF V project reported that through many international collaborations, research and student exchange programmes, BRD is paying great care of transferring bio-samples and their bioactive components while conducting biotechnological research. By implementing some annexes of NP-ABS measures in MoU/contract of BRD, the BDR partner university and BRD itself can monitor the right to ABS of utilizing TK and GRs among parties, and applying articles n. 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 17 and 23 of NP-ABS in enhancement of current MoU in BRD (pers. comm. BRD Former Director). Collaboration agreement between were signed between the BRD and the Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences of China for conducting R&D activities on Myanmar´s GR, in particular on rice.

References

- Seidel, V. Plant-derived chemicals: A source of inspiration for new Drugs. Plants 2020, 9, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIPO (Ed.) Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual Property—Background Brief. 2021. Available online: https://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/briefs/tk_ip.html (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Lenzen, M.; Moran, D.; Kanemoto, K.; Foran, B.; Lobefaro, L.; Geschke, A. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature 2012, 486, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). Achieving Environmental Sustainability in Myanmar, 2nd ed.; ADB: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2015; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Rosendal, G.K. Balancing Access and Benefit Sharing and Legal Protection of Innovations from Bioprospecting: Impacts on Conservation of Biodiversity. J. Environ. Dev. 2006, 15, 428–447. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1070496506294799 (accessed on 1 December 2006). [CrossRef]

- Reid, W.V.; Sarukhán, J. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 1st ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Sahota, A. Sustainability: How the Cosmetics Industry Is Greening Up, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2014; p. 333. [Google Scholar]

- Laladhas, K.P.; Nilayangode, P.; Oommen, V.O. Biodiversity for Sustainable Development, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- UEBT (Union for Ethical BioTrade). Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS). Basic Information Sheet; UEBT: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka, R. The negotiating history of the Nagoya Protocol on ABS: Perspective from Japan. J. Intellect. Prop. Assoc. Jpn. (JIPAJ) 2012, 9, 56–66. Available online: https://www.ipaj.org/english_journal/pdf/9-1_Kohsaka.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2012).

- CBD. The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity; CBD: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Avillés-Polanco, G.; Jefferson, D.J.; Almendarez-Hernández, M.A.; Belatrán-Morales, L.F. Factors that explain the utilization of the Nagoya Protocol Framework for Access and Benefit Sharing. J. Environ. Dev. J. Intellect. Prop. Assoc. Jpn. (JIPAJ) 2019, 11, 18. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/20/5550 (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- UNCTAD. 20 Years of BioTrade. Connecting People, the Planet and Market (b); United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. BioTrade and Access and Benefit Sharing: From Concept to Practice. A Handbook for Policymakers and Regulators; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. Biodiversity and Trade: Promoting Sustainable Use through Business Engagement (a); Report of the III BioTrade Congress; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Helvetas. Regional Biotrade Project South-East Asia (Vietnam, Lao PDR, Myanmar). 2016. Available online: https://www.helvetas.org/Publications-PDFs/reg_biotrade_ppt_eng_nov2016_full.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Mittermeier, R.A. Hotspots Revisited, 1st ed.; Cemex: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- Tun, Z.N.; Dargusch, P.; McMoran, D.; McAlpine, C.; Hill, G. Patterns and Drivers of Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Myanmar. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. A Global Standard for the Identification of Key Biodiversity Areas, 1st ed.; Version 1.0; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/Rep-2016-005.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Forest Department. NBSAP (National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2015–2020; Forest Department: Naypyitaw, Myanmar, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Khurtsia, K. Inle Lake Conservation and Rehabilitation, Stories from Myanmar; UNDP: Yangon, Myanmar, 2015; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.C. Understanding the drivers of Southeast Asian biodiversity loss. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingalls, M.L.; Diepart, J.-C.; Truong, N.; Hayward, D.; Niel, T.; Sem, T.; Phomphakdy, M.; Bernhard, R.; Fogarizzu, S.; Epprecht, M.; et al. The Mekong State of Land, 1st ed.; Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern and Mekong Region Land Governance, Bern Open Publishing (BOP): Bern, Switzerland, 2018; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). Deforestation Rates Myanmar; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- MCRB. Briefing Paper Biodiversity, Human Rights and Business in Myanmar; Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business: Yangon, Myanmar, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources: Gland, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- MOECAF (Ministry of Environmental conservation and Forestry). Inle Lake Long Term Restauration and Conservation Plan; MOECAF: Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, 2014; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Wangthong, S.; Palaga, T.; Rengpipat, S.; Wanichwecharungruang, S.P.; Chanchaisak, P.; Heinrich, M. Biological Activities and Safety of Thanaka (Hesperethusa crenulata) Stem Bark. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 132, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiverling, E.V.; Klein, A.M.; Bacik, L.C.; Gelsdorf, C.; Ahrns, H. Sun protection and other uses of Thanakha in Myanmar. Curr. Res. Integr. Med. 2017, 2, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Jeyaseeli, L.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Palchoudhuri, S.; Roy, D.S.; De, B.; Dastidar, S.G. Possibilities of Developing New Formulations for Better Skin Protection from a Traditional Medicinal Plant Having Potent Practical Usage. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2014, 4, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiverling, E.; Trubiano, J.; Williams, J.; Ahrns, H.; Craft, D.; England, M. Analysis of the Antimicrobial Properties of Thanaka, a Burmese Powder Used to Treat Acne. J. Biosci. Med. 2017, 5, 77589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Undurraga, J.T. Analysis of the Thanakha’s Market Potential through the Implementation of Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) and BioTrade Principles in Myanmar, 1st ed.; Bern University of Applied Sciences, School of Agricultural, Forest and Food Sciences, HAFL: Bern, Switzerland, 2018; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- ABSCH (The Access and Benefit-Sharing Clearing-House). Myanmar—Country Profile. 2014. Available online: https://absch.cbd.int/en/countries/MM (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. Available online: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/11735/2/thematic_analysis_revised (accessed on 17 June 2018). [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UEBT. Fair and Equitable Benefit Sharing. Manual for the Assessment of Policies and Practices along Natural Ingredient Supply Chains; Union for Ethical BioTrade: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CBD. Myanmar Overview. 2018. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/countries/?country=mm (accessed on 13 August 2018).

- Law Plus. Myanmar’s IP Laws Passed by the Upper House. 2018. Available online: https://www.lawplusltd.com/2018/02/myanmars-ip-laws-passed-upper-house/ (accessed on 13 August 2018).

- Mancini, M.C. Localised agro-food systems and geographical indications in the face of globalisation: The case of Queso Chontaleno. Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACB. Institutional and Policy Review of Access and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) Frameworks of Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam; ASEAN Center for Biodiversity (ACB): Laguna, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Kite Tales. Rice Wine: From Crop to Cup. 2018. Available online: https://kite-tales.org/en/article/rice-wine-crop-cup (accessed on 25 August 2018).

- Singla, A. Protection of Traditional Knowledge in India with Reference to Neem, Turmeric, Basmati Rice, 1st ed.; O.P. Jindal Global University: Sonipat, India, 2020; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, C. The Tragedy of the Commons in Plant Genetic Resources: The Need for a New International Regime Centered around an International Biotechnology Patent Office. Yale Hum. Rts. Dev. LJ 2001, 4, 63. Available online: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yhrdlj/vol4/iss1/3 (accessed on 18 February 2014).

- Smith, D.; Hinz, H.; Mulema, J.; Weyl, P.; Ryan, M.J. Biological control and the Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit sharing—A case of effective due diligence. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, M.S.; Nawata, E. Introduction of Thanakha (Limonia acidissima) and a Diversified Farming System into Yinmarbin Township, Sagaing Region, Myanmar. Trop. Agric. Dev. 2016, 60, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutry, M.; Allaverdian, C.; Mellac, M.; Huard, S.; Thein, U.S.; Win, T.M.; Sone, K.P. Land Tenure in Rural Lowerland Myanmar. From Historical Perspectives to Contemporary Realities in the Dry Zone and the Delta; GRET: Yangon, Myanmar, 2017; p. 302. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl Sampath, P. Regulating Bioprospecting: Institutions for Drug Research, Access and Benefit Sharing; United Nations University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; p. 267. [Google Scholar]

- Kiester, A.R. Aesthetics of Biological Diversity. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1996, 3, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- UCR (University of California Riverside). Hesperathusa (Naringi) Crenulata. 2008. Available online: https://citrusvariety.ucr.edu/citrus/Hesperathusa.html (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Berdegue, J.; Ospina, P.; Favareto, A.; Aguirre, F.; Chiriboga, M.; Escobar, J.; Fernández, I.; Gomez, I.; Modrego, F.; Ramirez, E.; et al. Determinantes de las Dinámicas de Desarrollo Territorial Rural en América Latina; Rimisp-Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kariyawasam, K.; Tsai, M. Access to genetic resources and benefit sharing implications of Nagoya Protocol on providers and users. J. World Intellect. Prop. 2018, 21, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Facilitating BioTrade in a Challenging Access and Benefit Sharing Environment (c); United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tengö, M.; Brondizio, E.S.; Elmqvist, T.; Malmer, P.; Spierenburg, M. Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 2014, 43, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, J.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A.; et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—Connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, M.J. Sharing the benefits of biodiversity: A new international protocol and its implications for research and development. Planta Medica 2011, 77, 1221–1227. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=caba6&AN=20113257775 (accessed on 20 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Hailu, B.; van Schalkwyk, F. Open Data and Transparent Value Chains in Agriculture. A Review of Literature; World Wide Web Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- National Information Sharing Mechanism (NISM-GPA). Implementation of the Global Plan of Action for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of PGRFA. 2018. Available online: www.pgrfa.org/gpa/mmr/mmrwelcomeil.html (accessed on 27 August 2018).

| Project | Period |

|---|---|

| 1. ASEAN ABS Project Building capacity for implementing CBD provisions on access to genetic resources and sharing benefits | 2011–2014 |

| 2.UNDP-China Trust Fund Project Support for Ratification and Implementation of the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing in ASEAN Countries | 2015–2016 |

| 3.UNDP/GEF Project Strengthening human resources, legal frameworks and institutional capacities to implement the Nagoya Protocol | 2016–2019 |

| 4.UN Environment/GEF Project Effective implementation of Myanmar’s commitments under the Nagoya Protocol through enhanced policies on access and benefit sharing from utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge | Started in 2019 |

| Level | Entity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NCA |

| Designated by the National Focal Point |

| Coordination mechanism | Cabinet committee on ABS | Composed by the National Focal Point and the designated NCA to discuss and resolve national ABS issues |

| Parliamentary Liaison | Cabinet Committee on ABS shall establish a liaison unit that will work with the Parliament on ABS issues | |

| Involvement with communities and other holders | Coordination mechanisms established to involve communities and other stakeholders, including the business sector and the academic community on ABS related issues | |

| Implementing actions | Technical working group | Lead by the MoNREC ECD for identifying actions and resources necessary to establish and enhance the national institutional and policy ABS framework |

| STRENGTHS | WEAKNESSES |

|

|

| OPPORTUNITIES | THREATS |

|

|

| Opportunities | Challenges |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giuliani, A.; Undurraga, J.T.; Dunkel, T.; Aung, S.M. Access and Benefit Sharing and the Sustainable Trade of Biodiversity in Myanmar: The Case of Thanakha. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212372

Giuliani A, Undurraga JT, Dunkel T, Aung SM. Access and Benefit Sharing and the Sustainable Trade of Biodiversity in Myanmar: The Case of Thanakha. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212372

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiuliani, Alessandra, José Tomás Undurraga, Theresa Dunkel, and Saw Min Aung. 2021. "Access and Benefit Sharing and the Sustainable Trade of Biodiversity in Myanmar: The Case of Thanakha" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212372

APA StyleGiuliani, A., Undurraga, J. T., Dunkel, T., & Aung, S. M. (2021). Access and Benefit Sharing and the Sustainable Trade of Biodiversity in Myanmar: The Case of Thanakha. Sustainability, 13(22), 12372. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212372