Professional Development of In-Service Teachers: Use of Eye Tracking for Language Classes, Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Professional Development for Technology Supported Education

1.2. In-Service Teacher’s Professional Development in Lithuania

1.3. Video Recording Feedback

1.4. Eye Tracking in Research

1.5. Class Interaction with Educational Technological Equipment

2. Materials & Methods

2.1. Research Objectives

2.2. Research Question

- How can eye tracking be used as a technology for the professional development of a language teacher focusing on the effective technology implementation in a cognitive load theory-based instruction?

2.3. Research Methodology

- The pair of teachers consisted of one expert and one novice;

- The teachers were paired according to the subject matter of their teaching;

- The teachers were also paired in their classes. Both teachers have to teach the same grade of students;

- Recorded lessons have also to be on the same topics.

- Two Lithuanian language teachers (first language, L1);

- Two Russian language teachers (second language, L2); and

- Two English language teachers (third language, L3).

- Number of visits (NV): the measurement of the number of visits within the active Area of Interest (AOI) or AOI group.

- Time to first fixation (TFF): the measurement of how long it takes before a test participant fixates on the active AOI or AOI group for the first time.

- Number of fixations (NF): the measurement of the number of times a participant fixates within the AOI or AOI group.

- Fixation duration (FD): the measurement of the duration of each participant fixation within an AOI (or within all AOIs which belong to an AOI group).

3. Results

3.1. Experiment Settings

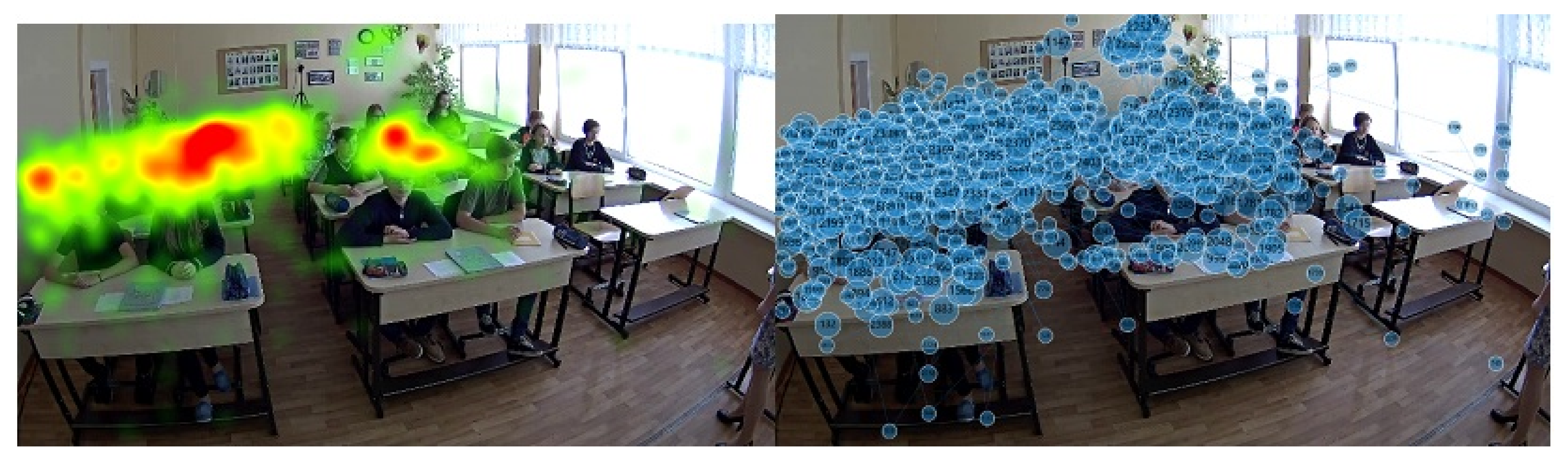

3.2. Eye Tracking Results

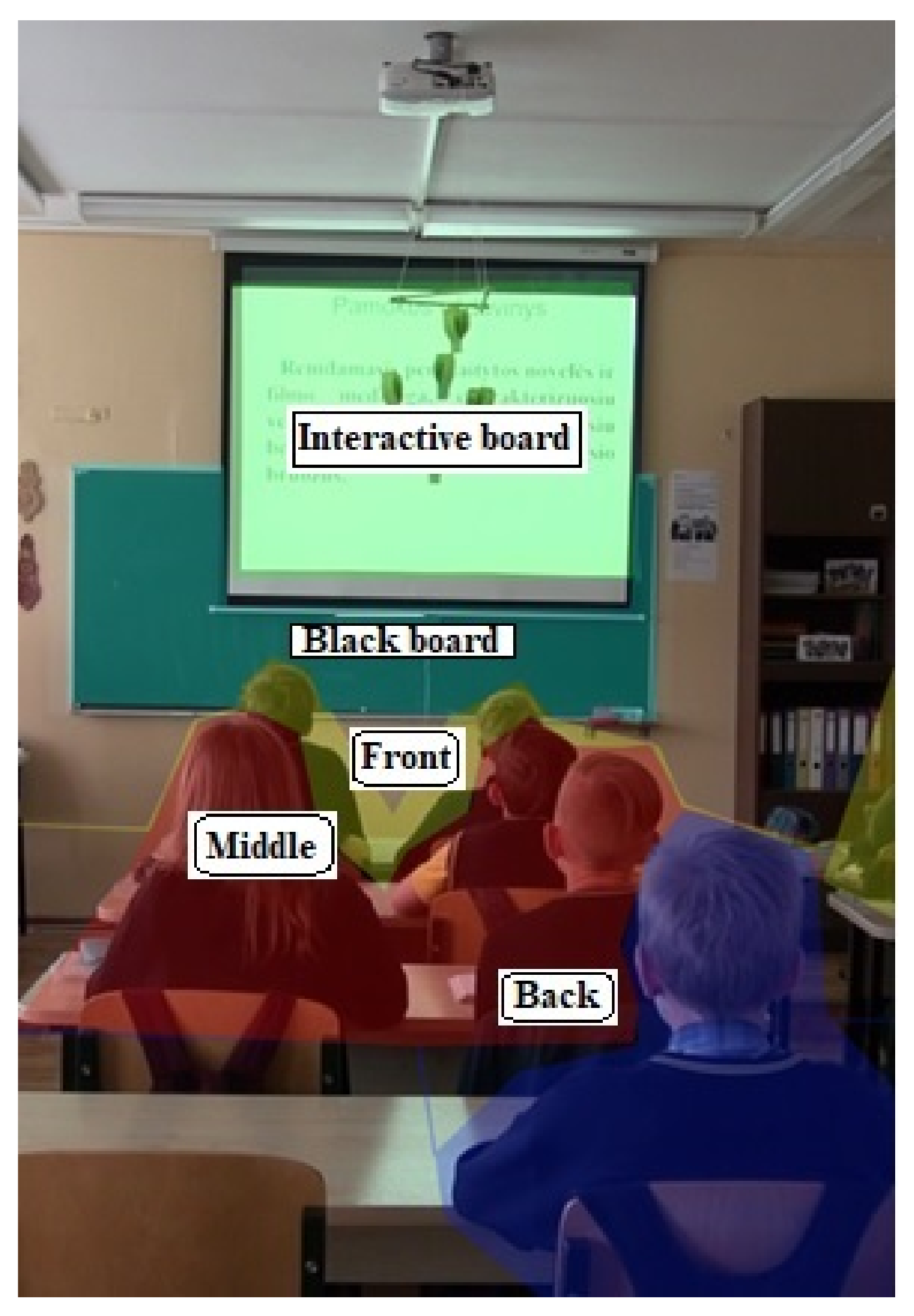

3.2.1. Interactive Board Analysis

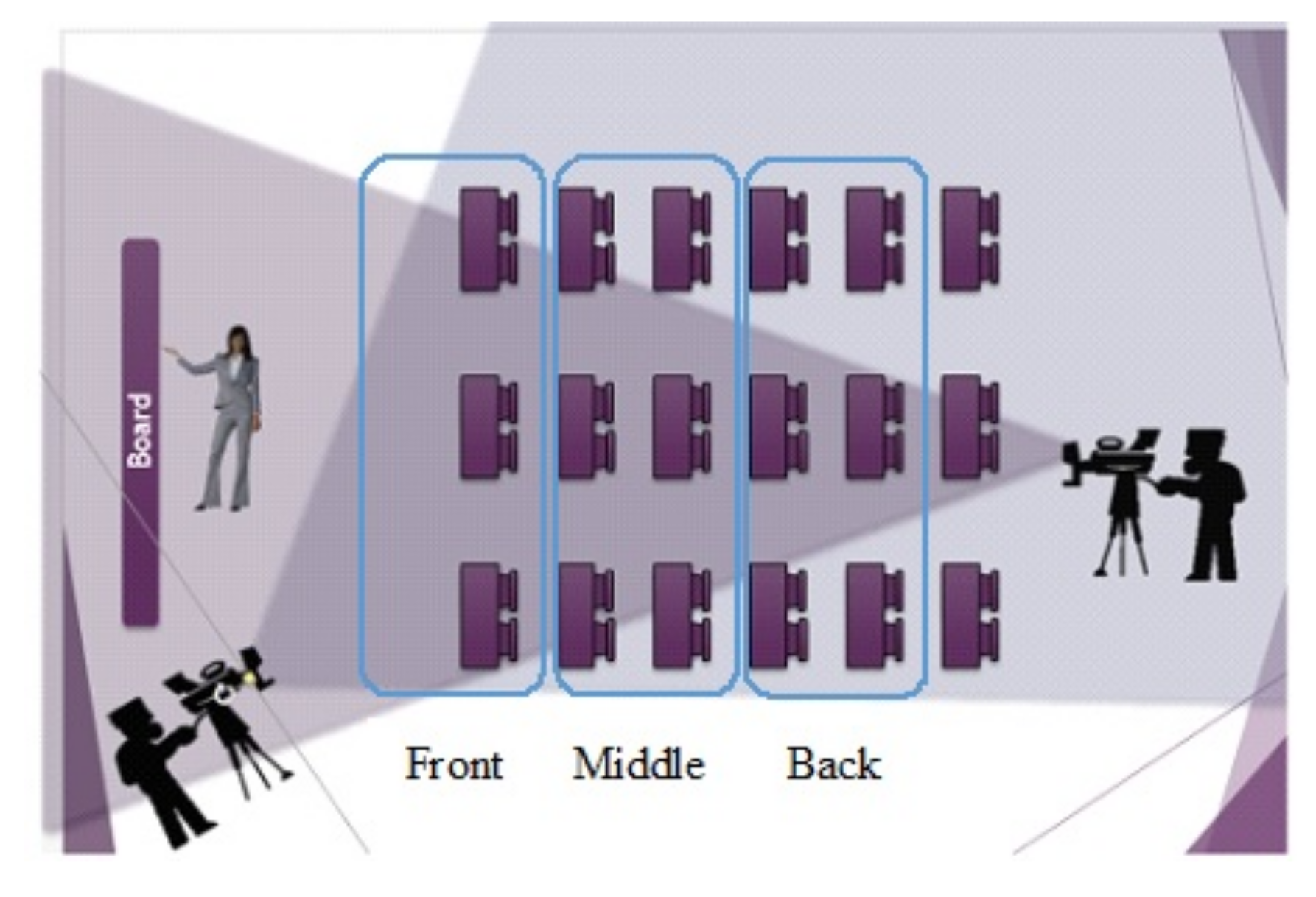

3.2.2. Horizontal Layout Analysis

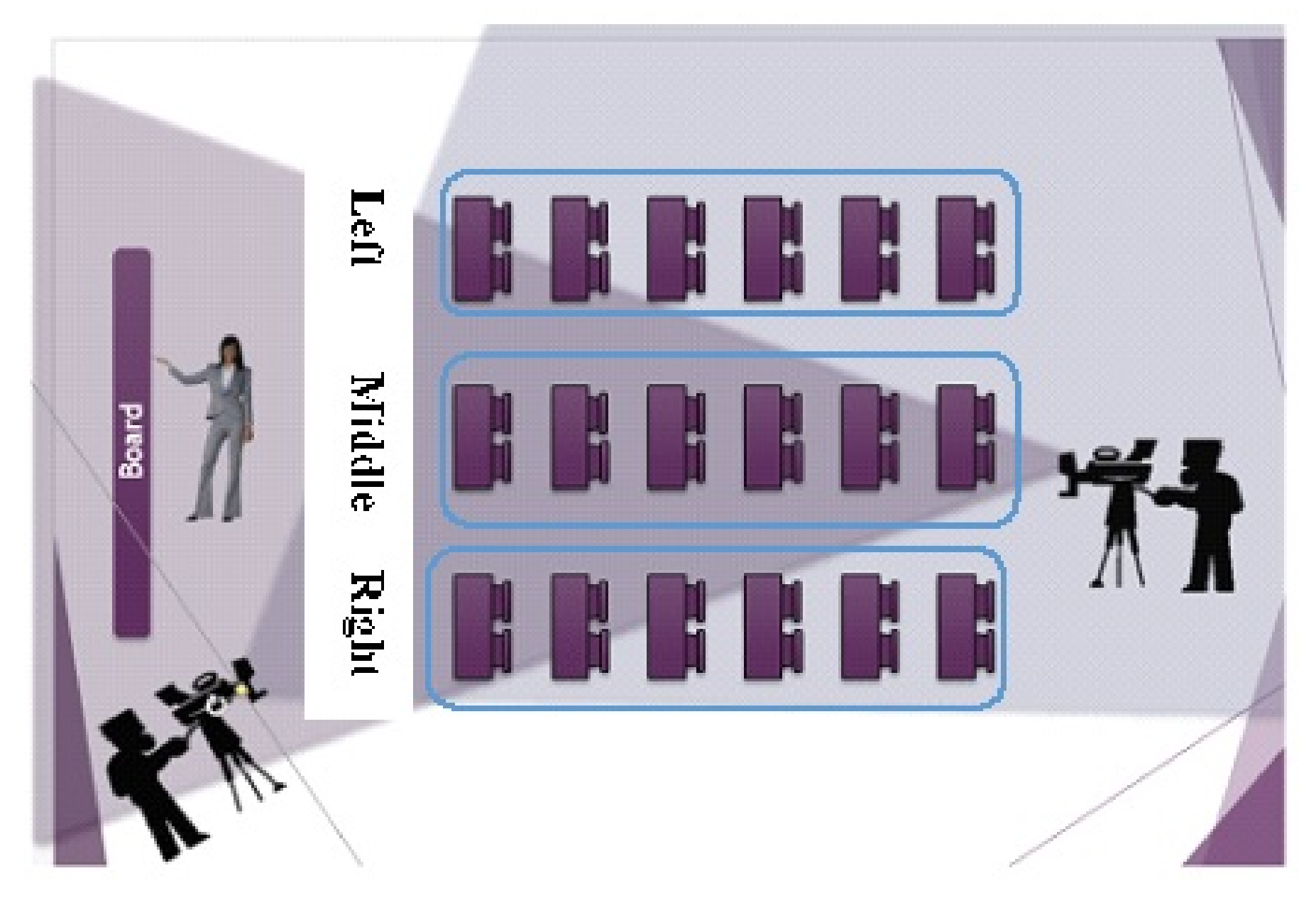

3.2.3. Vertical Layout Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Professional Development through Self-Reflection

4.1.1. Motivation

4.1.2. Classroom Management

4.1.3. E-content Material Usage

4.1.4. Eye Tracing on the Interactive Board

4.2. Policy Makers’ (Educational Experts’) Observations and Recommendations

4.2.1. Introduction

- What do you think about using technological equipment and e-learning materials in the course you are viewing?

- Did the teachers use various technological equipment in the video you observed? If so, how has this technological equipment been integrated?

- In your opinion, has the use of an eye tracking device and recording of the course affected the course?

- How do you evaluate the course you are looking at in terms of using technology, and classroom management, taking into account the lessons you have already been following?

4.2.2. Use of Technological Equipment and e-Learning Content

4.2.3. Different Technological Equipment Integration and Effects of Eye Tracking Device

4.2.4. Assessment of the Course in Terms of Technology Use, Classroom Management

4.3. Additional Topics

5. Conclusions

5.1. ICT Competencies and ICT Usage in Class

5.2. Student Centerd Education and Non-Verbal Communication

5.3. Self-Reflection and Class Work Improvements

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Self-Reflection Interview Questions

Appendix A.1. Motivation

Appendix A.2. Recording

Appendix A.3. Class

Appendix A.4. Teacher’s Lessons

Appendix A.5. Lessons of Colleagues

Appendix B. Equipment and Recordings

- One video from the teacher’s point of view (POV) with the teacher’s voice and teacher’s gaze in the tracking data mapped on the video frames;

- Video recordings of the classroom (one view each from the front and back of the classroom) with audio recording from one microphone (used for manual synchronization with the teacher’s POV recording);

- Automatic projection of the teacher’s gaze at data from manually selected time intervals of gaze at manually selected screenshots from the lesson video footage (synchronized with the teacher’s gaze and POV video footage, synchronized manually).

Appendix C. Data Analysis Methods

References

- Uztosun, M.S. In-Service Teacher Education in Turkey: English Language Teachers’ Perspectives. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2018, 44, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory, Learning Difficulty, and Instructional Design. Learn. Instr. 1994, 4, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khong, H.K.; Kabilan, M.K. A Theoretical Model of Micro-Learning for Second Language Instruction. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load Theory and Educational Technology. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedushko, S.; Ustyianovych, T. Predicting Pupil’s Successfulness Factors Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Mathematical Modelling Methods. In Proceedings of the Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Kiev, Ukraine, 26–27 January 2019; Volume 938, pp. 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurydice. Conditions of Service for Teachers Working in Early Childhood and School Education; European Education and Culture Executive Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/conditions-service-teachers-working-early-childhood-and-school-education-43_en (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- European Commission. 2nd Survey of Schools: ICT in Education; Technical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/euodp/data/storage/f/2019-03-19T084831/FinalreportObjective1-BenchmarkprogressinICTinschools.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Sun, J.; van Es, E.A. An Exploratory Study of the Influence That Analyzing Teaching Has on Preservice Teachers’ Classroom Practice. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 66, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablić, M.; Mirosavljević, A.; Škugor, A. Video-Based Learning (VBL)—Past, Present and Future: An Overview of the Research Published from 2008 to 2019. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2020, 26, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, M.; Menninga, A.; Steenbeek, H.; van Geert, P. Improving Language Use in Early Elementary Science Lessons by Using a Video Feedback Intervention for Teachers. Educ. Res. Eval. 2020, 25, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, L.P.; Magnuson, P.; Dillenbourg, P.; Saar, M. Reflection for Action: Designing Tools to Support Teacher Reflection on Everyday Evidence. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2020, 29, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, N.; Besselink, E.; Oosterheert, I. The Power of Video Feedback with Structured Viewing Guides. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 66, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinknecht, M.; Gröschner, A. Fostering Preservice Teachers’ Noticing with Structured Video Feedback: Results of an Online- and Video-Based Intervention Study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 59, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilop, C.N.; Weber, K.E.; Kleinknecht, M. Effects of Digital Video-Based Feedback Environments on Pre-Service Teachers’ Feedback Competence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.E.; Prilop, C.N.; Kleinknecht, M. Effects of Blended and Video-Based Coaching Approaches on Preservice Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Perceived Competence Support. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2019, 22, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, T.J.; Blazar, D.; Gehlbach, H.; Gehlbach, H.; Quinn, D.M.; Thal, D. Can Video Technology Improve Teacher Evaluations? An Experimental Study. Educ. Financ. Policy 2020, 15, 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, E.B.; East, A.; Thrush, N. Effects of a Video-Feedback Intervention on Teachers’ Use of Praise. Educ. Treat. Child. 2015, 38, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukkink, R.G.; Tavecchio, L.W.C. Effects of Video Interaction Guidance on Early Childhood Teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.E.; Gold, B.; Prilop, C.N.; Kleinknecht, M. Promoting Pre-Service Teachers’ Professional Vision of Classroom Management during Practical School Training: Effects of a Structured Online- and Video-Based Self-Reflection and Feedback Intervention. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2018, 76, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vattøy, K.D.; Gamlem, S.M. Teacher–Student Interactions and Feedback in English as a Foreign Language Classrooms. Cambridge J. Educ. 2020, 50, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarodzka, H.; Holmqvist, K.; Gruber, H. Eye Tracking in Educational Science: Theoretical Frameworks and Research Agendas. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.I.; Navarro, Ó.; Ortega, M.; Lacruz, M. Evaluating Multimedia Learning Materials in Primary Education Using Eye Tracking. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2018, 59, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, O.; Molina, A.I.; Lacruz, M.; Ortega, M. Evaluation of Multimedia Educational Materials Using Eye Tracking. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 197, 2236–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemdag, E.; Cagiltay, K. A Systematic Review of Eye Tracking Research on Multimedia Learning. Comput. Educ. 2018, 125, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, N.; Bråten, I.; Salmerón, L. Does Reading Medium Affect Processing and Integration of Textual and Pictorial Information? A Multimedia Eye-Tracking Study. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 62, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.; Rosa, P.J. Eye-Tracking as a Research Methodology in Educational Context: A spanning framework. In Early Childhood Development: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, edited by Information Resources Management Association; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.A.; Jarodzka, H.; Klassen, R.M. Capturing Teacher Priorities: Using Real-World Eye-Tracking to Investigate Expert Teacher Priorities across Two Cultures. Learn. Instr. 2019, 60, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiella, F.; Mannese, E.; Savarese, G.; Plutino, A.; Lombardi, M.G. Eye-Tracking Glasses for Improving Teacher Education: The e-Teach Project. Res. Educ. Media 2019, 11, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewska, M.; Kotoniak, P. Development of Program Comprehension Skills by Novice Programmers–Longitudinal Eye Tracking Studies. Inform. Educ. 2020, 19, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, C.; Holmes, K. “It Gives You That Sense of Hope”: An Exploration of Technology Use to Mediate Student Engagement with Mathematics. Heliyon 2020, 6, e02945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comi, S.L.; Argentin, G.; Gui, M.; Origo, F.; Pagani, L. Is It the Way They Use It? Teachers, ICT and Student Achievement. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2017, 56, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, A. ESL Teachers’ Use of ICT in Teaching English Literature: An Analysis of Teachers’ TPCK. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 34, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Assar, S. Information and Communications Technology in Education. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Second Edition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9780080970875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Flores, J.; Rodríguez-Santero, J.; Torres-Gordillo, J.J. Factors That Explain the Use of ICT in Secondary-Education Classrooms: The Role of Teacher Characteristics and School Infrastructure. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 68, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunuc, S.; Kuzu, A. Confirmation of Campus-Class-Technology Model in Student Engagement: A Path Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.K.W.; Yang, M. Using ICT to facilitate instant and asynchronous feedback for students’ learning engagement and improvements. In Emerging Practices in Scholarship of Learning and Teaching in a Digital Era; Springer: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 9789811033445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, F.; Mailok, R.; Ubaidullah, N.; Ahmad, U. The Effect of Project-Based Learning Against Students’ Engagement. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2016, 6, 6891–6895. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296672247_THE_EFFECT_OF_PROJECT-BASED_LEARNING_AGAINST_STUDENTS’_ENGAGEMENT (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Denscombe, M. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0335226863. [Google Scholar]

- Tobii, A.B. Eye Tracker Data Quality Report: Accuracy, Precision and Detected Gaze under Optimal Conditions-Controlled Environment; 2018. Available online: https://www.tobiipro.com/siteassets/tobii-pro/accuracy-and-precision-tests/tobii-pro-spectrum-accuracy-and-precision-test-report.pdf/?v=1.1 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Tobii, A.B. Eye Tracking for Research. Available online: https://www.tobiipro.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Guo, Q.; Tao, J.; Gao, X. Language Teacher Education in System. System 2019, 82, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, G.; Hubbard, P. Language Teacher Education and Technology. Handb. Technol. Second Lang. Teach. Learn. 2017, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, P.; McConnel, J. Eye Tracking Methodology for Studying Teacher Learning: A Review of the Research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2019, 42, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, G.G. Preventive and Classroom-Based Strategies. Handb. Classr. Manag. 2014, 2, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatkovski, B.; Kochoska, J. Communicative-Pedagogical Features of Communication in the Educational Process-Communicative Competence. In Proceedings of the International Conference of the Faculty of Educational Sciences, Shtip, North Macedonia, 24–25 September 2015; pp. 405–408. Available online: https://js.ugd.edu.mk/index.php/AMC/article/view/1484 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Muhonen, H.; Pakarinen, E.; Rasku-Puttonen, H.; Lerkkanen, M.K. Dialogue through the Eyes: Exploring Teachers’ Focus of Attention during Educational Dialogue. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 102, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeki, C.P. The Importance of Non-Verbal Communication in Classroom Management. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2009, 1, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, W.; Holland, S. The Fear of New Technology: A Naturally Occurring Phenomenon. Am. J. Bioeth. 2009, 9, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Salloum, S.A.; Hassanien, A.E.; Shaalan, K. Fear from COVID-19 and Technology Adoption: The Impact of Google Meet during Coronavirus Pandemic. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.J.; Baudry, J.; Mahr, D.; Sanchez, G.; Tancoigne, E. “Citizen Science”? Rethinking Science and Public Participation. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2019, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instructional Effect | Required Skills for Effective Integration of Technology into Instruction | ICT Integration Competences |

|---|---|---|

| Worked example | Timely transition from interpersonal to inter-technological sources of communication | General ICT competences and ICT usage in class; ICT integration and competences for classroom management; ICT integration for student engagement and motivation; ICT integration and support for student-centered education; Non-verbal communication; Self-reflection for improved teaching. |

| Split-attention | Managing and processing split-source interactive information | |

| Modality | Managing technology that supports consistent multimodal interaction | |

| Transient | Managing technology in a manner to support reduction of transiency | |

| Redundancy | Managing the clustered information on request and in real-time | |

| Expertise reversal and element interactivity | Content personal adaptation and interpersonal communication skills | |

| Working memory depletion | Skill to form, prioritize and dose instructional chunks |

| ICT Integration Competence | Primary Areas of Interest | Eye Tracking Variables Supporting the Competence |

|---|---|---|

| General ICT competences and ICT integration and usage in class | AOIGC, AOITT, AOITC, AOITM AOIIB | Regarding the AOITT area, NF is in favor of AOITM compared to AOITC. This optimizes the time to process information and minimizes the teacher’s interaction time with the computer. NV and FD in AOITT are small compared to other areas. This reduces the time for non-teaching activities and indicates sufficient ICT proficiency. NV in favor of AOIB compared to AOITT. |

| ICT integration and competences for classroom management | AOIGC, AOIV1-3, AOIH 1-3, AOIB…, AOIP…, AOIIB | The NV for the different subject areas is balanced. This allows for an even distribution of attention among the students during the lesson. The same applies to FD, but some variation is allowed as different “problem” areas require additional attention from the teacher. In interactive whiteboard-supported learning, subject areas are favoured for NV, allowing for classroom management activities. |

| ICT integration for student engagement and motivation | AOIGC, AOITT, AOIIB, AOIGO | TFF in favour of subject areas over ICT-related areas. TFF in favour of AOIIB over other ICT-related areas. This allows for earlier engagement and motivation of students. NV in favour of classroom areas compared to AOIGO area, supporting an active teaching style. |

| ICT integration and support for student-centered education | AOIGC, AOIIB | FD of AOIGC and AOIIB are balanced in support of an interactive teaching style that engages students in activities during the lesson. NV is in favor of interactive classroom equipment over assistive ICT equipment for the teacher. This allows the focus to be on the learning process itself, avoiding additional activities such as managing the ICT equipment. |

| Non-verbal communication | AOIV1-3, AOIH 1-3, AOIB1-…, AOIP1-… | TFF differences on different subject areas should be minimized and NV and FD balanced, maintaining an even distribution of attention. |

| Self-reflection for improved teaching. | Different class areas of interest | A self-reflective comparative analysis of the results of the experiment (all variables are involved). The comparative study is conducted in the following dimensions: (1) within the same lesson; (2) between lessons of the same teacher; (3) between teachers/lessons of the same subject; (4) between different subjects. This allows for the adoption of advanced teaching styles and the use and personalization of best teaching practices. |

| Lesson | T-LE | T-LN | T-RE | T-RN | T-EE | T-EN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of recordings | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Lessons topics covered | Grammar: verbs | Literature: analysis of the work of the Lithuanian author | With whom we are friends? Grammar | Friendship. A song for the 3rd grade pupils entitled “The friendship is not a work” | Myth and legends | Grammar: revision of Past Continuous |

| Literature: analysis of the work of the Lithuanian author | Grammar: a Verb | Portrait of a friend. Grammar | With whom we are friends? Grammar | Grammar: negative form, positive form, and questions | Breaking the low. Vocabulary, text understanding | |

| Grammar: Nouns | Literature: artistic expressions to describe the nature in works of literature. | Searching for a friend. Grammar | Portrait of a friend. Grammar | Reading and understanding the text from textbook | Biography of famous people I | |

| Literature: artistic expressions to describe the nature in works of literature. | Grammar: a Noun | True friend | - | Writing biography of famous people | Biography of famous people II |

| Lesson | T-LE | T-LN | T-RE | T-RN | T-EE | T-EN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment used | Multimedia projector—presentation, video | Multimedia projector—presentation and video | Multimedia projector—presentation, tasks | Multimedia projector—video clip | Multimedia projector—interactive material, video, material from websites, tablets | Multimedia projector—interactive educational material |

| Number of students by lesson | 14 | 19 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| 14 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 12 | |

| 13 | 17 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 11 | |

| 13 | 18 | 7 | - | 12 | 11 |

| Teacher Code | Average Visit Count on Board | Average Fixation Duration on Board | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactive Board (%) | Black Board (%) | Interactive Board (%) | Black Board (%) | |

| T-LN | 75.00 | 25.00 | 75.00 | 25.00 |

| T-LE | 95.00 | 5.00 | 94.69 | 5.31 |

| T-EN | 89.04 | 10.96 | 92.17 | 7.83 |

| T-EE | 76.91 | 23.09 | 87.03 | 12.97 |

| T-RN | 88.16 | 11.84 | 98.55 | 1.45 |

| T-RE | 82.95 | 17.05 | 90.23 | 9.77 |

| Teacher Code | Average Visit Count | Average Fixation Duration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front (%) | Middle (%) | Back (%) | Front (%) | Middle (%) | Back (%) | |

| T-LN | 31.73 | 39.93 | 28.34 | 33.73 | 41.53 | 24.74 |

| T-LE | 21.06 | 47.90 | 31.04 | 21.32 | 51.45 | 27.24 |

| T-EN | 26.35 | 34.16 | 39.49 | 25.37 | 34.85 | 39.78 |

| T-EE | 15.55 | 41.47 | 42.98 | 19.14 | 35.31 | 45.56 |

| T-RN | 14.38 | 35.86 | 49.76 | 13.59 | 36.66 | 49.75 |

| T-RE | 19.25 | 29.18 | 51.57 | 19.80 | 34.83 | 45.38 |

| Teacher Code | Average Visit Count | Average Fixation Duration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left (%) | Middle (%) | Right (%) | Left (%) | Middle (%) | Right (%) | |

| T-LN | 61.34 | 32.53 | 6.14 | 63.89 | 31.07 | 5.04 |

| T-LE | 9.93 | 31.13 | 58.95 | 6.15 | 22.56 | 71.30 |

| T-EN | 58.05 | 26.60 | 15.35 | 55.93 | 30.01 | 14.06 |

| T-EE | 59.30 | 23.66 | 17.05 | 58.28 | 22.62 | 19.11 |

| T-RN | 43.07 | 14.70 | 42.23 | 47.37 | 11.33 | 41.30 |

| T-RE | 75.12 | 9.93 | 14.96 | 82.96 | 5.92 | 11.11 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dagienė, V.; Jasutė, E.; Dolgopolovas, V. Professional Development of In-Service Teachers: Use of Eye Tracking for Language Classes, Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212504

Dagienė V, Jasutė E, Dolgopolovas V. Professional Development of In-Service Teachers: Use of Eye Tracking for Language Classes, Case Study. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212504

Chicago/Turabian StyleDagienė, Valentina, Eglė Jasutė, and Vladimiras Dolgopolovas. 2021. "Professional Development of In-Service Teachers: Use of Eye Tracking for Language Classes, Case Study" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212504

APA StyleDagienė, V., Jasutė, E., & Dolgopolovas, V. (2021). Professional Development of In-Service Teachers: Use of Eye Tracking for Language Classes, Case Study. Sustainability, 13(22), 12504. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212504