Abstract

As many universities in non-Anglophone countries have committed to internationalising their academic programmes, more content courses in Arts and Sciences are being taught in English. When content courses are taught in English in a country where English is not the first language, this is called English Medium Instruction (EMI). Using specific country cases, previous studies have confirmed that an EMI course can pose many challenges to the learning of course content by students. To date, there have been few attempts to examine these challenges through a large-scale qualitative prism, which would be useful for gaining new insights in order to inform policy as well as classroom interventions. In this systematic thematic synthesis we have aimed to identify the obstacles to implementing learner-centred pedagogy in EMI tertiary programmes, focusing on student perspectives. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) and Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) were used to appraise and synthesise 40 empirical articles. The articles included 1769 participants in 20 non-Anglophone countries and jurisdictions. The participants were both local and international non-native English-speaking students enrolled in EMI courses. The synthesis yielded 46 descriptive themes stratified into six analytical domains. The suggested domains are meta/linguistic, instructional, meta/cognitive, socio-cultural, affective, and institutional obstacles. They suggest that students in different regions faced quite similar challenges in their EMI courses. The challenges consist of inadequate use of English by students and lecturers, and a lack of student-centred pedagogy, particularly in teacher–student and student–student interactions. The findings of most learner-centred EMI studies revealed that the main challenges came from English comprehension (the first three suggested domains); fewer studies included factors related to the learning environment (the last three domains). This review can inform university administrators, teaching staff and researchers engaged in internationalising higher education and aid in designing appropriate EMI programmes that offer better learner-centred educational experiences.

1. Introduction

A recent global survey of 907 higher education (HE) institutions from 126 countries has revealed that internationalisation is becoming more common around the world [1], with more universities, especially in non-English speaking countries, prioritising the future sustainability of tertiary programmes offered in English [2]. Sustainability is becoming an important measure in assessing the long-term effectiveness of English-medium programmes on many levels, from sustaining student learning and classroom engagement to sustaining faculty training and certification [3,4,5,6].

Defined as ‘the use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions in which the majority of the population’s first language is not English’ [7], English Medium Instruction (EMI) has been shown to be a ‘growing global phenomenon’ [2] as well as ‘the most significant trend in educational internationalisation’ [8] and it ‘is developing at such a remarkable speed that it is often beyond the control of policymakers and educational researchers’ [7]. In higher education, students’ perspectives and experiences have been extensively researched, with findings informing professional development programmes, pedagogical interventions, and institutional planning [9,10,11,12,13].

To date, a few studies have explored the key outcomes of EMI for students, such as second language (L2) improvement and content learning [9,10,11,12,14]. These studies have contributed to the growing evidence that EMI may pose significant challenges to students whose first language is not English [13,15]. Despite such important efforts to assess and highlight the role of L2 in content learning (with some studies pointing to the context-specific nature of implementation [16,17]), from the growing body of learner-focused literature the impression may be given that success in EMI is mainly about students’ linguistic needs and metalinguistic affordances. Even though there are comparatively fewer studies that address non-linguistic challenges, these demonstrate that sustaining effective EMI pedagogy might require more systematic approaches to assessing learners’ needs and concerns [13].

Considering that the advantages of learner-centred pedagogy are well established within HE research [18,19,20,21,22,23], it is surprising that it has not been thoroughly addressed by EMI scholars. Researchers exploring the classroom experiences of EMI learners have focused on specific pedagogical interventions within specific geographic, disciplinary, or institutional contexts [24,25,26,27], rather than taking a comprehensive approach to exploring what makes an EMI classroom learner-centred. Perhaps for the same reason, Macaro and his colleagues in their influential review stressed the urgency of understanding the ‘accommodation needs’ of EMI students in order to ensure that they are effectively learning the course content [9]. In his book, Macaro [7] discusses the merits of implementing constructivist pedagogy in an EMI classroom, a process he refers to as ‘quality interaction in pedagogy’ and which we will further discuss in the next section.

Moreover, while numerous models, types, and characteristics of EMI [7,28,29,30] have been proposed, an in-depth qualitative overview of student experience beyond linguistic issues is nonetheless lacking. Exploring the pedagogical practices of lecturers that university students themselves find problematic is necessary in order to align the goals of educational internationalisation and EMI policy to student expectations. In addition, exploring the obstacles to ‘learner-centred’ EMI pedagogy from the perspective of learners in HE is critical for assessing the validity of existing ‘success’ metrics [10,11,31].

The previous reviews to which we are able to compare our study were conducted by Macaro et al. [9], Williams [32], and Kremer and Valcke [33]. The review of EMI done by Macaro et al. [9] is perhaps the most renowned study in this area, and investigated the beliefs of university teachers and students and provided evidence on whether EMI was of benefit to developing English proficiency without associated detrimental effects on content learning. Williams, on the other hand, reviewed research with reference to the South Korean context [32], while Kremer and Valcke’s conference paper reviewed studies published before 2013 to examine didactic strategies employed by teachers and students in EMI classrooms [33]. Although all three studies provide useful insights into EMI research and practice, none of the papers shed light on the challenges of learner-centred EMI pedagogy from a student perspective, nor do they confine their methodologies to primary qualitative studies as we have in this study. Because of the unique systematic synthesis methodology we have adopted, the present study approaches EMI from a different perspective.

Along with teacher-oriented EMI studies, learner-focused research has been dominated by large-scale quantitative data [7]. While quantitative data provide numerically more accurate insights into certain variables and relationships within EMI, such models often omit microfactors that may be statistically insignificant, but contextually important. Qualitative studies, on the other hand, can help lecturers, researchers, and administrators identify what learner-centred pedagogy means to students; a considerable number of such studies has indeed been conducted. These studies are often not given the attention they deserve, partly because each has been conducted within a specific context, sample or research problem. To gain a more comprehensive view of learner-centred EMI pedagogy, our aim in this study is to combine the results of multiple qualitative studies into a synthesis that offers a range of meanings, experiences, and opinions provided by student participants in a variety of EMI contexts. The depth, scope and rigour of our thematic synthesis compared to a single study may also have greater potential to influence EMI policy and inform pedagogical practice [34].

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

2.1. Learner-Centred Pedagogy in HE

Learner-centred pedagogy acknowledges students’ diverse needs and abilities as well as individual preferences for constructing and re-constructing content knowledge. In a learner-centred classroom, lecturers prioritise students’ understanding rather than rote mastery of content subjects [35]. Although in the HE literature the term is not always used with consistent meaning [36,37], many authors have agreed that accompanying monologic lectures with interactive and innovative teaching methods improves learner engagement, critical thinking, motivation, and content learning. In addition, such conceptualisations (as shown in Table 1) have emphasised the importance of teacher–learner reciprocity, collaboration, active learning, quality feedback, intellectual challenge [18,21,23], students’ responsibility for learning, clear evaluation purpose and processes [19,21,23,38], engaging learners in solving real-world problems, application and demonstration of new knowledge, encouraging critical thinking [20,23,38], stimulation of student interest and motivation, learner control and autonomy [21,23,38], helping students construct meaning through relevant activities, lecturers’ systematic alignment of teaching and learning activities [22,38], building on students’ existing knowledge and skills, using dialogic teaching to support ‘visible’ learning [23], students and teachers as co-learners, and student–student interaction [38].

Table 1.

Learner-centred pedagogical frameworks in HE contexts.

2.2. Learner-Centred Pedagogy in HE and EMI

Previous research on students’ EMI experiences suggests that many factors can affect the effectiveness of learning content in English in higher education. The existing literature on student-perceived challenges in an EMI classroom can be broadly categorised into three groups. The first group includes studies exploring macro-level factors, such as national as well as institutional policies and practices that guide the implementation of EMI and have an effect on both lecturer and student experiences. Previous studies expose gaps that exist between both national- and institutional-level EMI policies and classroom-level practices [7,39]. These studies highlight contextual constraints on policy implementation [29], and called for more careful curriculum evaluation to inform context-sensitive ways to implement EMI policy [9,16]. Other studies emphasise the importance of teacher training and qualification [7,40] and institutional support for interdisciplinary as well as language instructor–content lecturer collaborations in universities that have increasing linguistically and culturally diverse student populations [41,42], as well as measures to improve students’ preparedness for EMI through effective design and delivery of EAP and ESP courses [43].

The second group of studies tend to focus on meso-level factors that include a wide range of pedagogical and linguistic challenges faced by students. These challenges are often externally driven and are associated with EMI lecturers’ choice of pedagogical strategies and their linguistic competence to provide an inclusive and effective EMI experience. For example, many studies focused on the impact of codeswitching, translanguaging, and bi/multilingual pedagogies on students’ learning and satisfaction [7,10,44,45,46]. Studies have also provided compelling evidence regarding the multidimensionality of EMI, as seen through different kinds of assessment approaches [28], differences between content-driven and language-driven EMI [28], and lecturers’ profiles, backgrounds, needs, and teaching styles [27,39,47,48].

The third group of studies look at micro-level factors to emphasise a range of personal and externally driven issues shaping students’ general satisfaction and learning outcomes in EMI courses. For example, studies have looked into the impact of linguistic and meta-linguistic competence for learning success [15,25,40,49,50,51] and numerous other factors associated with learners’ prior knowledge and schema building [52,53], previous experiences with EMI [31], skills in collaborative and cross-cultural learning [26,54], motivational and socio-emotional regulators [11,55,56], and other issues.

While it is evident that the learner-centric approach can potentially increase EMI students’ success and satisfaction rates, to date there have been few attempts in the EMI literature to systematically explore learner-centred pedagogy. One of the confounding factors is that in addition to content learning, EMI brings a critical ‘E’ factor into play, that is, English. A recently proposed working definition of an EMI course [57] highlighted the critical role of language in designing and delivering content courses, by suggesting that:

“For EMI courses, the delivery of content, whole-class interaction, the learning materials, and the demonstration and assessment of learning outcomes (such as oral presentation, assignments, or tests) should be in English. Other languages may be used in a principled and limited way in specific circumstances, for example, student-to-student and teacher-to-student interaction during pair work and group work may sometimes take place in languages other than English to aid mutual comprehension and idea generation. However, students should be asked to present their discussion outcomes in English and lecturers should ensure that at least 70% of class communication takes place in English”.

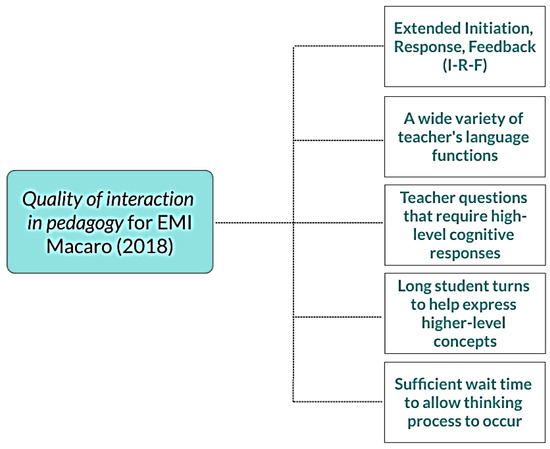

This conceptualisation has been influenced by the works of other scholars who previously proposed that interaction in the EMI classroom was ‘probably the most significant pedagogical resource that contributes to learning’ [7]. For instance, stemming from the interaction theories within the Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research, Macaro’s model refers to comprehensible input, incidental learning, negotiation of meaning, pushed output, and feedback as key ingredients of an interactive EMI process. Perhaps acknowledging that the use of these strategies may not necessarily indicate the presence of learner-centred pedagogy in an EMI classroom, and based on socio-cultural and constructivist theories of learning, Macaro further developed the notion of ‘quality interaction in pedagogy’ [7]. Although he did not use the term ‘learner-centred’, one can observe that the purpose of ‘quality interaction’ is not only to raise lecturers’ awareness of students’ diverse abilities and needs in an EMI classroom, but also to help lecturers design and deliver less monologic and more dialogic and interactive content courses in English.

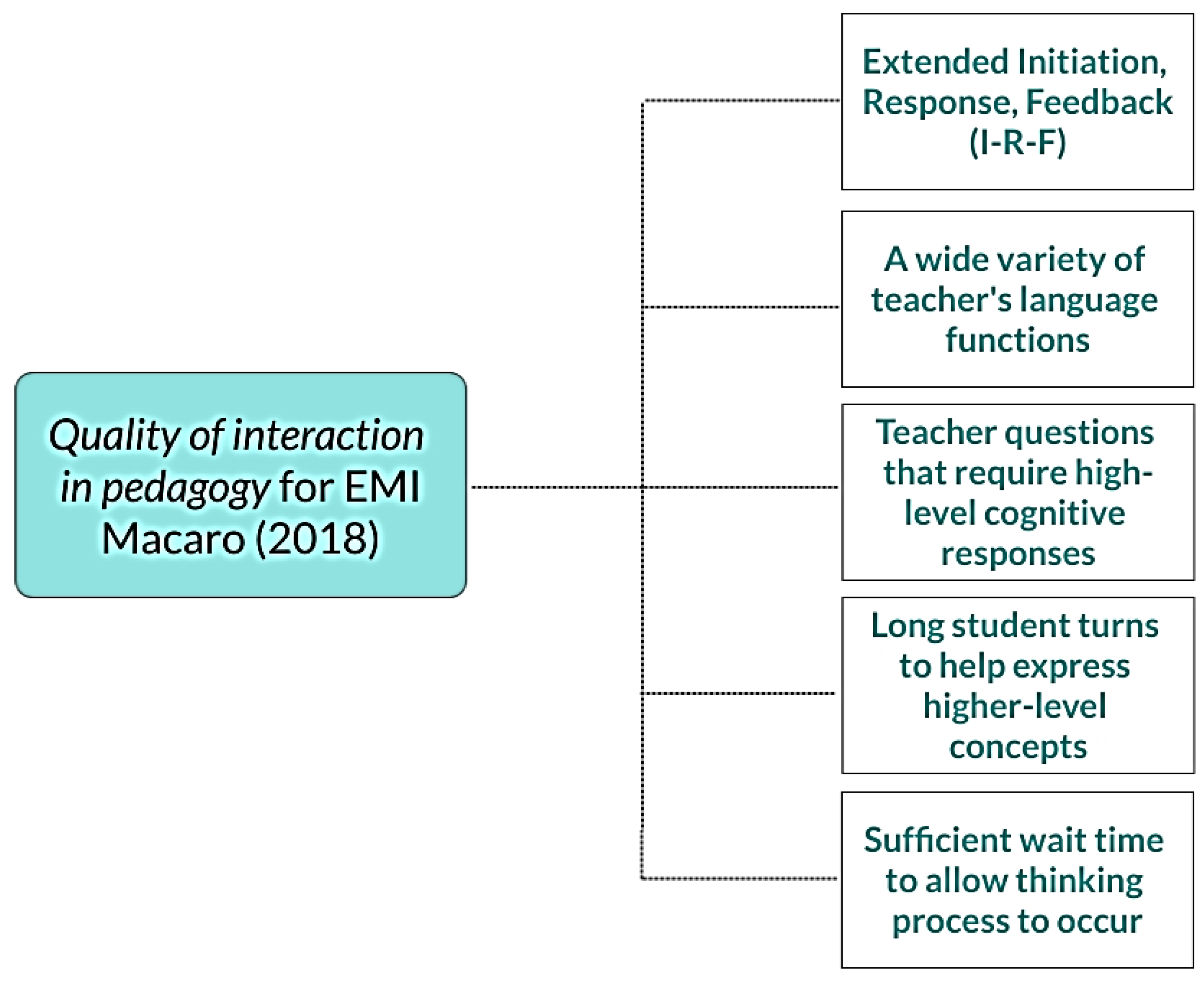

Macaro’s measures of quality interaction, as shown in Figure 1, reflect the key role of a constructivist pedagogy in EMI effectiveness by promoting ‘the student as an active participant in learning an academic subject, moving from preconceptions and misconceptions of how certain (for example, scientific) phenomena occur to a modification of those conceptualisations as a result of new experience, such as an interaction in the classroom’ [7]. Recently, this model has been tested in part in a study involving seven universities in Turkey, revealing significant differences in terms of the proportion of first language (L1) use and teacher–student interaction by university type, with less L1 use and interaction found in EMI classes at elite universities [30]. The study identified four variations of EMI pedagogical implementation with respect to language use and interaction: (1) English dominant and teacher-centred; (2) English-dominant interactive; (3) L1-dominant interactive; and (4) L1-dominant and teacher-centred. While such contributions to the research of learner-centred EMI pedagogy are significant, there is still room for broader empirical validation of such practices and the existing interrelationships within different student populations, disciplines, and institutions. Therefore, this study attempts to provide in-depth qualitative insights into the topic by thematically synthesizing student opinion and perceived challenges from a large body of primary qualitative research.

Figure 1.

Quality of interaction in EMI pedagogy (adapted from Macaro, 2018 [7]).

Consequently, the main research question that this study addresses is: What are the challenges faced by students enrolled in internationalising universities in different countries and what are the students’ views about the obstacles to implementing learner-centred pedagogy in English-medium academic courses?

3. Materials and Methods

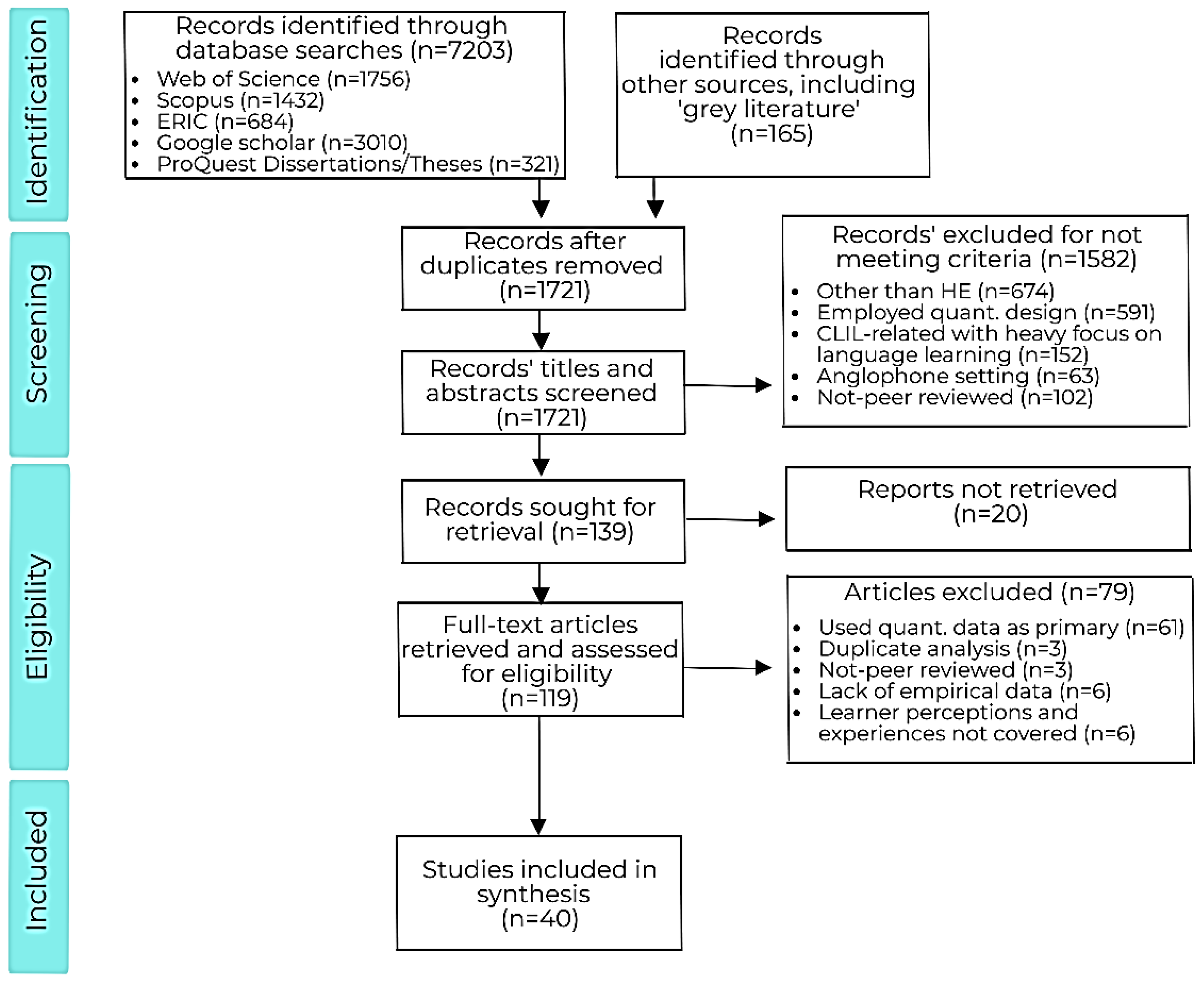

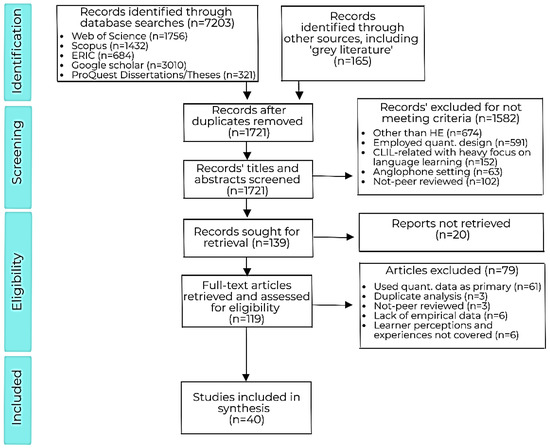

This systematic thematic synthesis study aimed to identify the challenges in using learner-centred pedagogy in EMI tertiary programmes from a student perspectives. We used an Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) approach to identify the essential articles for analysis and to report the results [58]. This approach suggested three main processes for article identification: literature search and selection (see Figure 2), quality appraisal, and data synthesis.

Figure 2.

The flow diagram of selection and screening processes.

3.1. Literature Search and Selection

Comprehensive searches were carried out in the Web of Science’s Core Collection, which included Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI), Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI), Book Citation Index (BCI), as well as in the Scopus, ERIC, and Google Scholar databases. Given the systematic scope of the study, we conducted additional searches in the ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database, which indexes abstracts and provides full-text access to dissertations and theses. We also searched the reference lists of relevant publications using forward and backward snowballing methods [59]. The search did not set restrictions on the language of publication. Quantitative studies and systematic reviews were excluded.

Author 1 (M.I.) used Boolean rules to build search strings consisting of multiple combinations of search terms. These search terms were further refined and discussed among the team of researchers (M.I., T.K.F.C., Y.Y., N.D.) and grouped into four broad categories, as shown in Table 2. We used 32 search string combinations in total. Examples of some of the search strings used are given below.

Table 2.

Terms and concepts used as search strings.

- TOPIC: (English medium instruction) AND TOPIC: (teaching) AND TOPIC: (students) AND TOPIC: (perceptions) AND TOPIC: (university).

- TOPIC: (EMI) AND TOPIC: (pedagogy) AND TOPIC: (students) AND TOPIC: (views) AND TOPIC: (higher education).

Table 3 shows the criteria which were used to guide the literature search and selection. Three authors (M.I., Y.Y., N.D.) independently screened the titles and abstracts, removed those that did not meet the inclusion criteria, and assessed full-text versions of the selected studies for eligibility.

Table 3.

Filtering criteria for search, selection, and quality appraisal.

3.2. Quality Appraisal

The comprehensiveness of the reporting in each primary qualitative study was assessed in two stages. Initially, independent reviewers (M.I., Y.Y., N.D.) used the CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [60], a set of ten items designed to be answered with ‘yes’/‘can’t tell’/‘no’ when critically assessing the comprehensiveness of each article. The studies that received at least 8 out of 10 ‘yes’ answers by two independent reviewers as well as the ones that used interviews and focus groups to examine student experiences were then subjected to an additional check using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) [61]. This framework allows reviewers to identify explicit and comprehensive reporting of studies that used in-depth interviews and focus groups to collect data and evaluate the transferability of the findings to their own settings. The COREQ’s 32 items are grouped into three domains: (i) research team and reflexivity; (ii) study design; and (iii) data analysis and reporting. Three authors (M.I., Y.Y. and N.D.) assessed each eligible study independently using the COREQ framework and resolved any disagreements through discussion. The authors followed a four-stage approach (identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion [62]) to select articles for further analysis; this process is illustrated in Figure 2.

3.3. Data Synthesis

This study used Thomas and Harden’s systematic thematic synthesis approach to analyse 40 selected articles [63]. This approach integrates the findings of multiple qualitative studies; the following five steps were used in the analysis:

- All included papers were read thoroughly by three authors.

- The first author then extracted and summarised the documents regarding their definition and context of EMI, country of research, sample size, characteristics of academic subjects, study design, methods of analysis, and key research questions (see Table 4).

Table 4. A stratified schema of participant quotations and references reporting each domain and theme.

Table 4. A stratified schema of participant quotations and references reporting each domain and theme. - The full-text articles and their descriptors were then assessed independently by three researchers (M.I., Y.Y., N.D.) using the CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [60] and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) [61], as mentioned earlier.

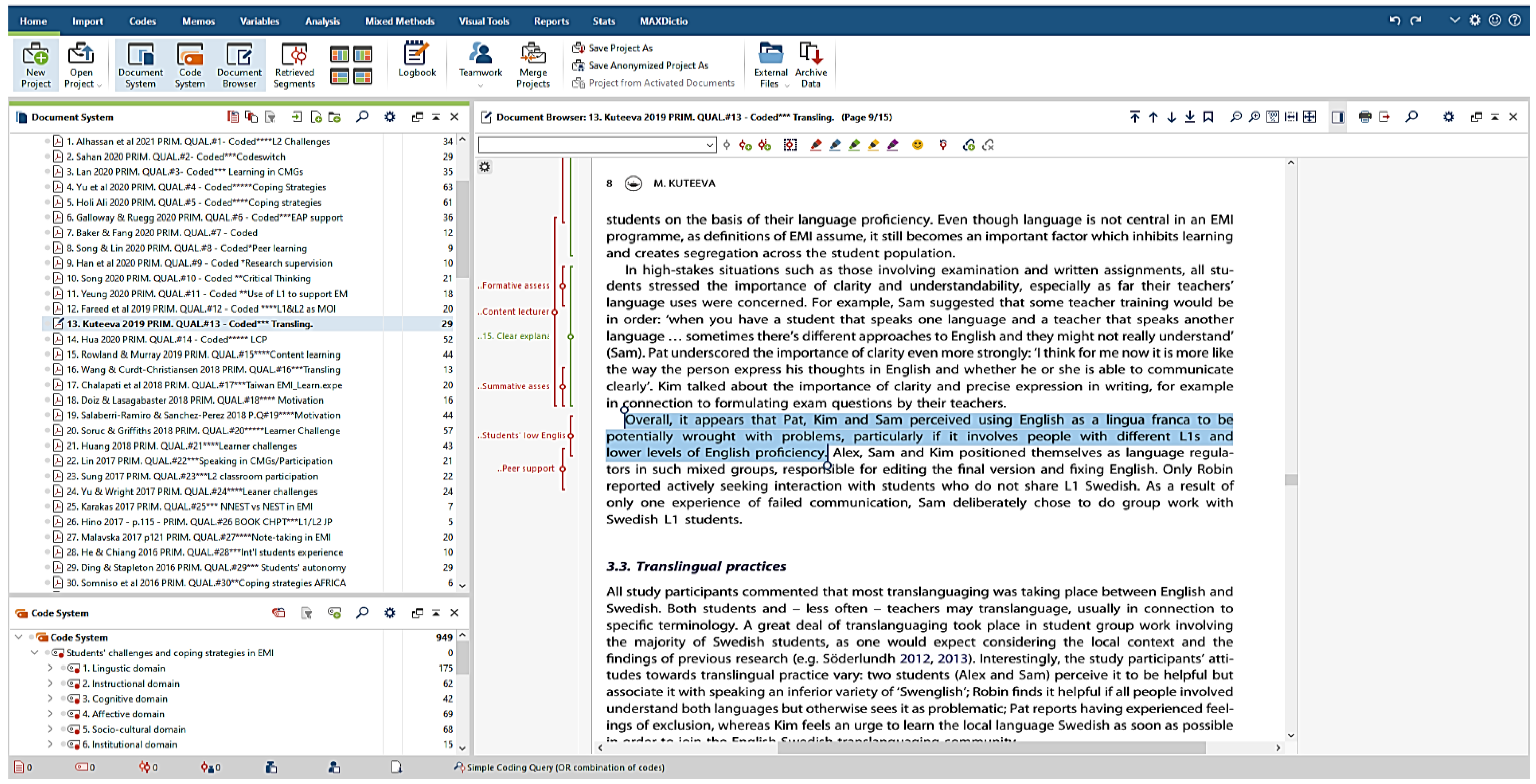

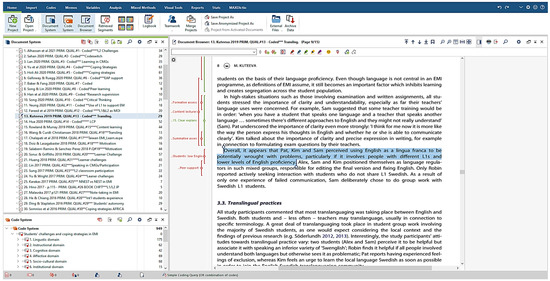

- Data from the results sections of the articles were independently and inductively coded by two authors (M.I., Y.Y, N.D.) line-by-line using MAXQDA Ver. 2020TM, a software programme designed for computer-assisted qualitative and mixed-method data, text, and multimedia analysis (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Line-by-line coding in MAXQDA Pro. 2020.

Figure 3. Line-by-line coding in MAXQDA Pro. 2020. - The results of open coding were organised into descriptive themes. Researchers (M.I. and T.K.F.C.) then compared the developed themes inductively and established the primary analytical domains [63].

The final process resulted in the inclusion of 40 studies that qualified for the synthesis. Detailed descriptors of the studies included in the synthesis are given in Appendix A.

4. Results

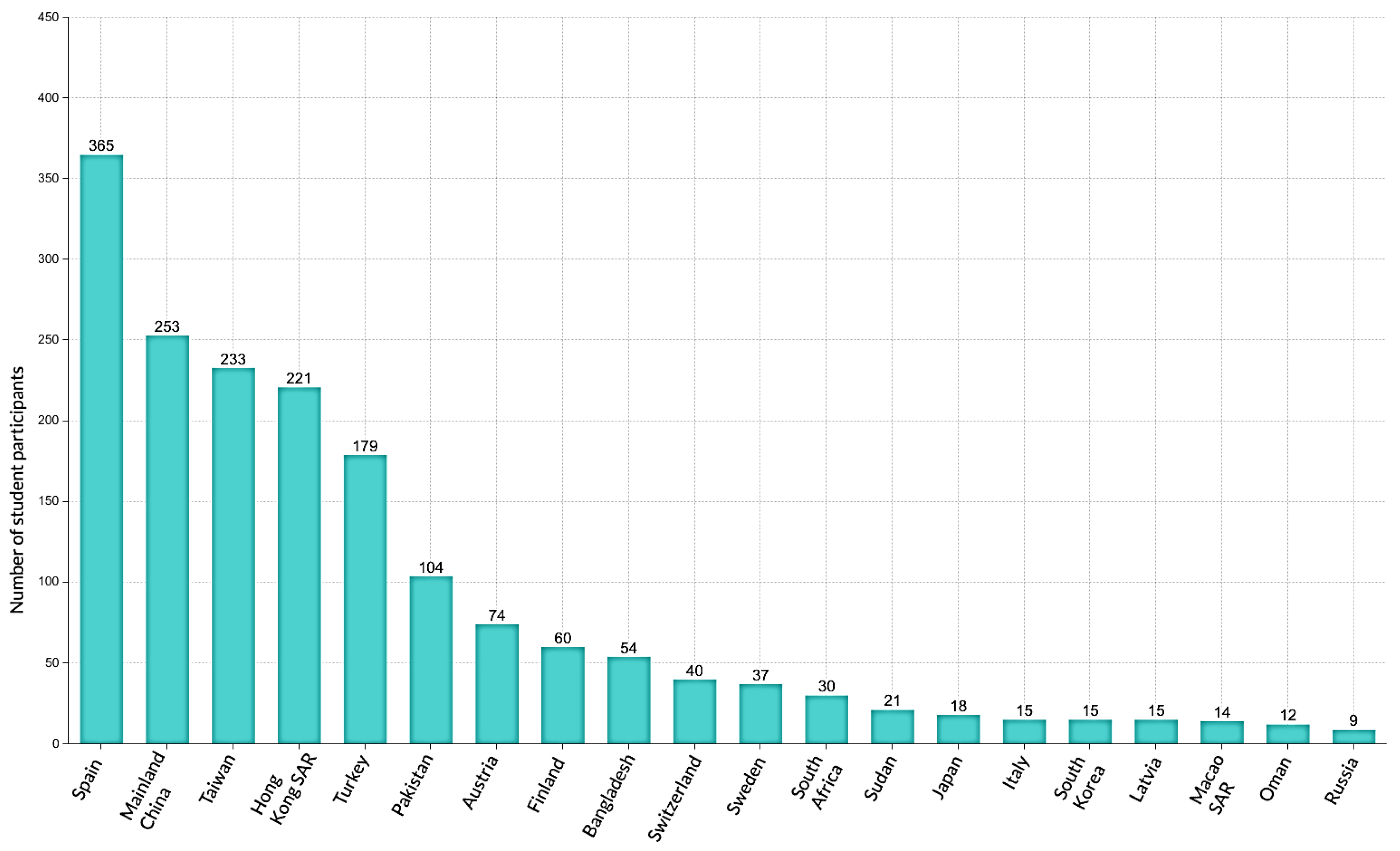

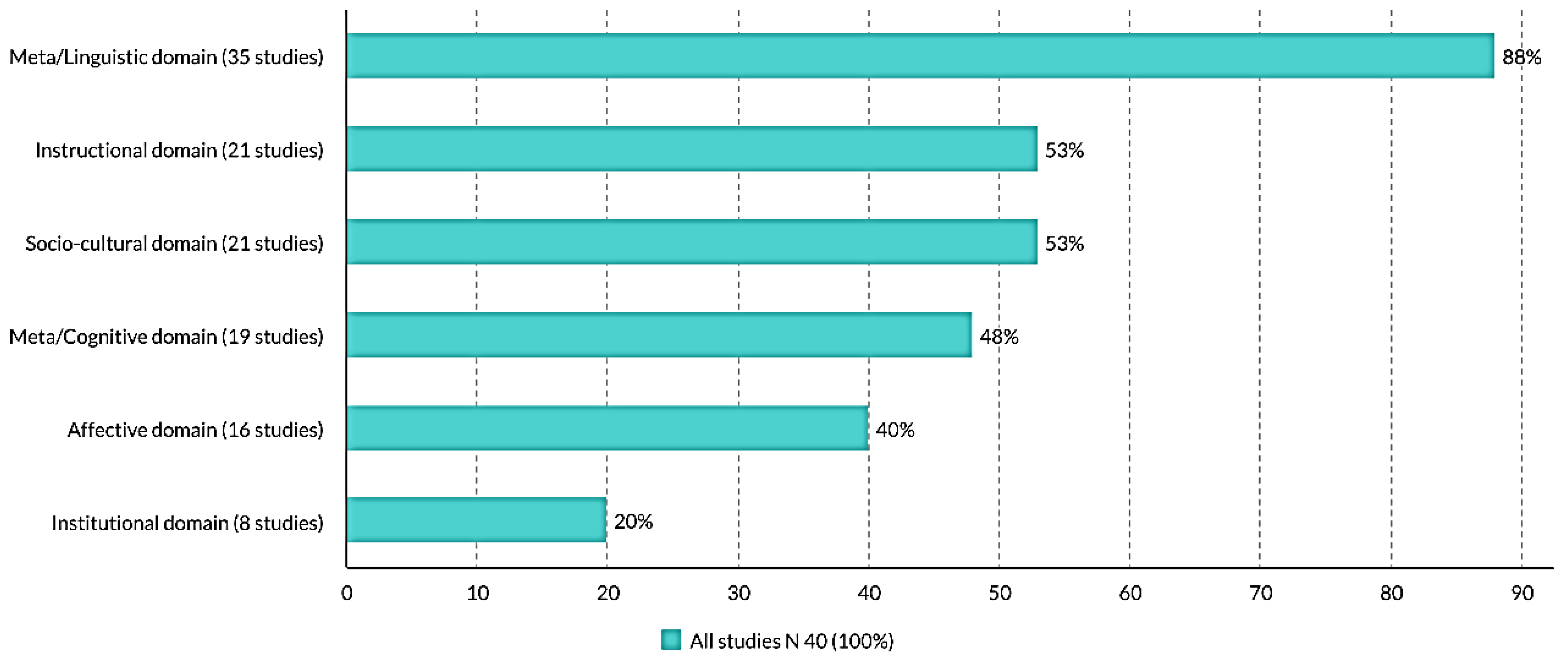

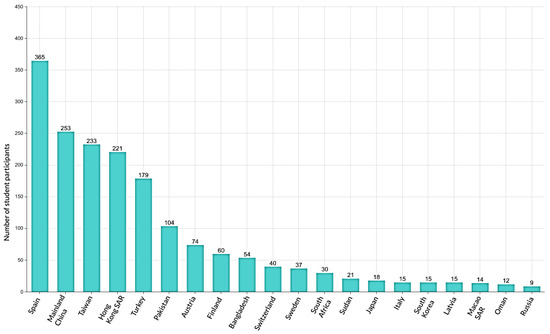

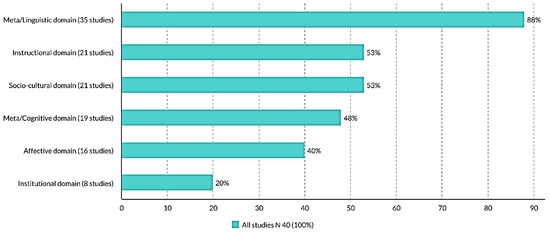

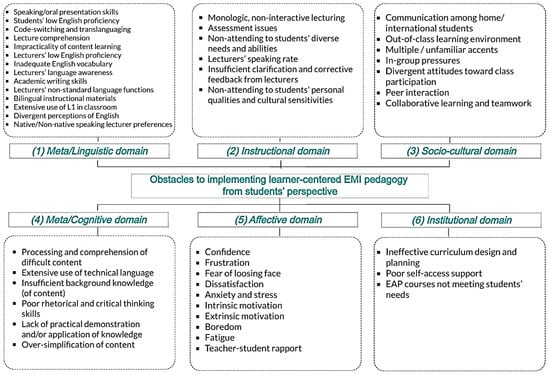

The selected 40 studies included 1769 participants from 20 countries and jurisdictions (see Figure 4). The six main analytical domains related to the issues and obstacles faced by students during their content learning with EMI were identified. These were the meta/linguistic (reported by 35 studies), instructional (21 studies), socio-cultural (21 studies), meta/cognitive (19 studies), affective (16 studies), and institutional domains (8 studies), as illustrated in Figure 5. Selected quotations illustrating each descriptive theme are provided in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Representation of student participants by country or jurisdiction (N = 1769).

Figure 5.

Distribution of studies across six analytical domains.

4.1. Meta/Linguistic Domain

First, we explored the themes related to the students’ attitudes toward content learning through EMI. Students referred to the impracticality of EMI for some content disciplines in 11 studies. Some students expressed concerns and negative feelings [64,65,68,70], while in other studies they voiced mixed or positive views regarding the practical utility of EMI for studying content [12,53,67,69,71,72]. In addition, students seemed to have divergent perceptions of English in content classrooms, especially when it comes to comparisons among international and home students [70,73,74,75,76]. Some international students believed they were ‘as much non-native English speakers’ as home students, however, they regarded English as ‘just a medium for communication’ and ‘felt no need to be concerned about making mistakes’ [73,74], whereas home students expected native-like English from teachers and peers alike [73]. Other students perceived English as ‘an imposed lingua franca’ that limited the possibility of ‘having courses delivered in both the local and other foreign languages’ [70].

Next, we examined a group of themes related to students’ and lecturer’s English proficiency, the strategies used, and their effects on learning. For both home and international students in at least 12 studies, concerns stemmed from adapting to a bilingual academic environment in which students had low general English proficiency. Students believed that their inadequate English was one of the leading causes of poor content comprehension [6,12,64,66,78], and as such this had a negative effect on their confidence ‘to speak in front of classmates’ [6,79] and their motivation to learn [82]. Many students pointed to the weaknesses of their academic English skills and attributed it to the lack of prior experience with English Medium Instruction [6,76,82]. Students’ use of coping strategies such as ‘looking for gestures, some verbs, some phrases’ in order to understand lecturers’ speech further highlights the depth of the problem [12]. The latter also seemed to influence students’ preference for non-native-speaking lecturers because native-speaking faculty ‘often speak too fast without realizing it’ [80]. Students with higher English proficiency believed that when the class has many students with low levels of English, some professors tended to ‘teach at an average level’ [74].

The participants in 10 studies believed that lecturers’ low English proficiency was another major hurdle for content comprehension [12,53,72,84], and that it prevented course instruction ‘in a deeper way’ and jeopardised class facilitation and engagement [12,84]. As some instructors were not properly trained to teach or communicate in English, this led to their committing noticeable grammatical and vocabulary errors when using spoken English [75,86]; thus, they often resorted to their L1 to teach courses [79]. Students suggested that universities should ‘test teacher’s levels of English’ or establish ‘certain language standards’ for EMI lecturers to help students perform better in their EMI courses [83,86]. This was perceived as a two-dimensional problem, in that ‘not only students find it hard to understand their teachers’ English, but it may be equally hard for content instructors to understand international students’ English’ [83,86]. Another related theme pointed to the lecturers’ non-standard language functions. Students referred to their inability to understand lectures due to lecturers’ English pronunciation, intonation, accent, or dialect [53,75,81,86,87] which ‘created difficulty in comprehension and caused the loss of concentration after 15 min of listening’ [75]. The lecturers’ accent especially seems to have affective and cognitive impacts on student learning [53,67,81,88]. On the contrary, when lecturers could successfully engage with students in ‘much the same way as they do in their native language’ the students mentioned that non-standard language functions became a secondary issue [87]. Some students ‘felt that the use of English did not impair their ability to understand course content delivery …due, in part, to the fact that their teachers are non-native speakers of English with more familiar accents and intonation’ [53]. The latter two themes provide some context for the recurrence of a theme related to native vs. non-native English-speaking lecturer preferences [53,71,80,88]. In one study, Turkish EMI students chose native speakers because of ‘better command of English and quality of education system’, while ‘better communication opportunities and better comprehension of lectures’ were reasons for preferring non-native-speaking lecturers. Other students had no specific preferences, provided lecturers showed ‘fluency and intelligibility’ and ‘expertise in the subject matter’ [80]. One could also relate this theme to the lecturers’ poor language awareness and support, reported in nine studies. Although in some studies students ‘felt that it is not the role of lecturers to help them with English’ [53], students also shared their ‘dissatisfaction with an EMI class that had little language support’ from instructors, and to a lesser degree, from their respective departments [74,78,83,89,90]. In most other cases, students made it clear that effective learning in an EMI course is not only about the quality of content and its delivery, but also the effective use of the primary medium of instruction, and that lecturers should be aware of their use of English [68,69,78,88,89,90].

Twelve studies have systematically addressed extensive code-switching, which refers to the alternation between languages in a specific communicative episode in an EMI classroom, such as an oral presentation or responding to a lecturer’s question [99]. On the one hand, due to their insufficient level of spoken English, lack of vocabulary knowledge or due to the difficulty of the content subject, many students welcomed the possibility of using their first language (L1) when they felt the need [12,53,67,74,75,76,91]. This practice was especially expected and tolerated when used by lecturers with unclear pronunciation and who lacked the ability to ‘put everything together’ in English [53,64,66,67,76,89,91]. On the other hand, extensive code-switching in class caused a backlash from international and a few home students who either did not speak the L1 (such as Spanish or Mandarin) or expected their EMI course to support their ‘genuine’ English learning [64,74]. In some cases, code-switching was intertwined with the act of translanguaging that brought together different dimensions of students’ personal history, experience, attitudes, and identities [100]. Switching to Swedish [78] or Cantonese [6] in the EMI lecture or team project allowed ‘peer communication on a different level’ and ‘to join the ‘elite’ group’ of L1 speaking students’ [78], or, conversely, was used by home students to disregard the needs of minority international students [6]. Indeed, the interrelationships between language fluency and codeswitching/translanguaging are not always linear. However, one can observe implications stemming from lecturers’ and students’ ‘abandonment of English’ in an EMI course altogether, preferring extensive use of L1 in the classroom instead, as reported in some studies [13,65,66,67,78,90].

Finally, we explored themes related to specific problems in an EMI classroom that exposed students’ problems and necessitated student-centred interventions. Students in nearly half of the studies had encountered problems with speaking and oral presentation in English, which affected their learning in various ways. The data specifically highlighted problems related to the lack of skills to ‘speak in English in class’ [12,66,68,91], participation in discussions [53,66,74,82,91], answering questions in English [12,52], pronunciation and peer reactions [68], ‘finding the right word’ [53], memorizing slides [81], ‘producing absurd sentences’ [12], and switching to L1 when unable to express an idea in English [74]. Some lecturers’ poor English and/or monologic teaching did not provide opportunities for practising speaking skills [64]. Students also mentioned that universities provided help with English writing skills, but there was no support for oral communication [89]. Some students attributed their poor speaking to cultural norms that encouraged more ‘listening’ than ‘speaking and arguing’ in class [73,81], whereas others felt ‘pressured by peers and teachers to participate in discussions’ due to their higher English fluency [6]. Students believed that oral participation played a key role in their acceptance in the peer group [92]. Another critical issue for many students was inadequate English vocabulary (10 studies) which manifested itself in specific issues such as understanding vocabulary used in the class, understanding themes, inferring vocabulary from context, decoding vocabulary while listening, remembering key vocabulary, and the need to constantly look up vocabulary using dictionaries and translation tools [12,13,65,68,90,91,93]. Another related subtheme that emerged pointed to the problem of academic writing in English (nine studies) which could be seen from poorly written assignments [90], students’ inability to compose longer essays [81], their weak knowledge of referencing and plagiarism-avoidance practices [6,81], and confusion caused by ‘different requirements at a new university’ [82]. Students pointed to various aspects of academic writing that presented a challenge, including format, structure, grammar, presentation, choice of words, and clarity [65,72,83,90,91]. Some mentioned the ‘need to do research, a lot of analysis, and discussion’ [6].

Eleven studies have systematically reported instances of students facing problems with EMI lecture comprehension. Namely, students had trouble when prioritizing listening and/or taking notes at the same time [12,91], with lecturer’s speech rate being too fast [75,91], in addition to learning and revising content that required more time, prolonged concentration, and additional energy compared with studying courses in the students’ native language [52,53,81,82]. Other factors included lecturers failing to explain terms or not adequately using discourse markers and logical connectors [75,86,88], as well as inability to comprehend and reflect on course materials in English [81]. Some students, especially those with no prior EMI experience, seemed to be especially worried about their comprehension in the first few weeks of their courses [81]. Poor lecture comprehension seems to be linked with incomprehensibility of instructions and tasks during examinations as well [66]. The use of comprehension strategies such as recording and listening to lectures several times [53], extensively using online translation tools [90], taking elaborate notes [12], printing out PowerPoint slides, and checking unfamiliar words and spelling [81,82] point to the students’ needs to cope with these problems on their own. Some other themes, such as bilingual instructional materials, could also relate to the problem of EMI lecture comprehension and course performance [12,13,53,65,67,79]. As some English textbooks and handouts were ‘wordy and complex’ [67], and as ‘understanding a new concept in written English takes a bit longer and you have to read a sentence more than once’ [53], students would prefer reading additional materials in their native language ‘to gain in-depth knowledge of the subject contents delivered in English’ [13]. However, in some settings where students were more fluent in English, they ‘preferred reading authentic rather than simplified or abridged materials’ in English [53]. In addition, some students were critical about ‘an imbalance in the use of teaching materials’ [79], in other words, lecturers’ overreliance on textbooks disregarded the students’ need to support learning with additional teaching materials such as videos.

4.2. Instructional Domain

This domain includes themes related to students’ views of content lecturers’ competencies and the instructional strategies used in EMI classrooms. Data extracts from 21 studies (53%) were synthesised into six themes. The most prevalent theme within the domain is related to students’ frustration with ‘monologic’ [84,87], non-interactive lecturing, which negatively affected students’ concentration, motivation and learning in an EMI classroom [6,12,52,53,64,67,79,84,86]. According to students, the EMI courses did not result in any learning when the classes were ‘teacher-fronted’ with ‘little opportunity to communicate with either teachers or peers’ [67], especially when ‘teachers narrated exactly what has been written in the textbooks’ or ‘just read from the PowerPoint slides that had already been uploaded to the Moodle [6,12,64,79,84,86]. Such an instructional approach had rendered ‘the class atmosphere completely dead’ [52]. Students were often disappointed to have ‘little or no discussions in class’ [86]. Such monologic teaching styles were often described by students as ‘traditional,’ ‘dull,’ ‘one-way delivery’, ‘teacher-fronted’, or ‘not internationalised’. [67,79,84]. Monologic instruction encouraged resistant behaviours, such as sleeping in class, using smartphones, chatting, and absences [52,84]. International students and some home students faced the need to adapt to classes that were more didactic and less interactive compared to what they had previously experienced [6]. Therefore, many students stressed the effectiveness of dialogic instruction, such as when lecturers encouraged informal discussions or ‘faced the students and kept them busy with questions [87]. Students referred to this approach as ‘useful,’ ‘active’ ‘engaging,’ and ‘interactive’ [64,84]. Students especially praised the use of group work and other strategies for classroom management and participation that compensated for the low language proficiency of lecturers and students [64]. Although there were students who thought that the interactive nature of the classroom represented a stark contrast with their prior education experiences, nonetheless these students did not necessarily consider it an instructional deficiency [6], pointing yet again to their own lack of oral communication skills. In addition to ‘interactive lecturing’ students also favoured ‘clear’ presentation of slides and explicit communication of each lesson’s objectives [87].

Along with lecturing style, students were also concerned with assessment issues when attending EMI content subjects (10 studies). In some cases, students found it ‘stressful’ that subject learning through EMI ‘might have an influence on their final marks because they have difficulties to express themselves in English’ [53,64] and some suggested that tests and exams should be flexible in allowing the use of students’ L1 [64,66]. Generally, students expected that formative and summative assessments should ‘obviously … assess subject knowledge rather than knowledge of English’ [53]. Occasionally, students felt it was unfair that the examinations in English ‘cater only for students who have either English-medium background or have good command over the language’ [66]. This was a serious concern ‘when classroom participation was part of the assessment criteria’ [6]. In other cases, students pointed to difficulties with lecture comprehension and the lack of ‘room for negotiating grades’ when lecturers did not speak students’ L1 [88]. The need to constantly use L2 also negatively affected the time management of some students for exam and graded assignment preparation [72]. Students who worked hard to complete their courses in English also expected to receive reports that certified their English proficiency in order to help them secure competitive jobs [67]. Students stressed the need for clarity and comprehensiveness, especially when lecturers’ English was not advanced [65,78]. Assessment issues were also raised in other contexts. On one occasion, students were concerned that their peers’ poor English explained the lecturers’ use of ‘easy’ and ‘non-challenging’ assessments [84]. In the same study, students pointed out that when lecturers failed to ‘demonstrate relevancy’ of the content, learning was reduced ‘merely to surviving in examinations’ [84]. Some students struggled to come to terms with many assessment varieties, such as ‘a mid-term test, a group project, an online discussion’ or often ‘heavily weighting towards written examinations’ which was too much of a burden, especially when students had no prior experience [6].

Students also felt that because a typical EMI course brings together students from all kinds of linguistic, cultural, and educational backgrounds, attending to students’ diverse needs and abilities when teaching course content would significantly enhance learning outcomes [6,12,52,79,82,84]. In one study, students pointed out that less proficient learners thought that ‘they do not receive the attention that they need from the lecturer’ [52]. In the perfect scenario, students expected that the ‘lecturers would listen to the students’ problems and advise and help in finding solutions whenever possible, encourage and appreciate their efforts, extend deadlines for the submission of assignments, respond positively to students’ weaknesses, and take care of each student individually …’ [12,79,82]. Students believed that EMI programmes should be designed to ‘offer flexibility in choice of courses and cater to students who learn at different paces’ [79]. Students also stressed the need for lecturers to attend to students’ personal and cultural sensitivities [6,73,82,83]. Some international students with higher levels of English ‘felt the pressure to speak in class when they have nothing to say’ [73]. This study pointed out that some lecturers indeed ignored ‘the fact that international students desire to remain silent at times and that some [home] students do develop a desire to speak.’ In another study, it was reported that the ‘lecturer publicly ridiculed the Rwandan students, indicating that they did not deserve to be studying’ on the programme for their poor critical thinking skills [82]. The disregard of cultural sensitivity in a multicultural EMI classroom may indeed lead to students’ attrition, as one Japanese student in South Korea had experienced [83]. In addition, students in five studies mentioned the lecturers’ speaking rate as a double obstacle for lecture comprehension [12,52,75,90,91] reported as ‘keeping up with the teacher and the topic’. The lack of clarification and corrective feedback from lecturers was another problem faced by students in five studies [13,65,75,83,90]. For example, some students failed to ‘complete assignments without clear guidelines and rubrics’ [65] or because of a lack of explanation of ‘unclear terms’ [75] and ‘subject-specific vocabularies’ [83]. As for corrective feedback, some students voiced concerns that their written assignments had many shortcomings, and the lack of feedback from lecturers only increased students’ anxiety [83].

4.3. Socio-Cultural Domain

This domain includes themes related to students’ learning in collaborative, culturally mixed and out-of-class environments. Data from 21 studies (53%) were synthesised and grouped into seven descriptive themes. One of the major recurring themes in this domain was the challenge of communication among home and international students. Although this and the following themes may not be directly related to EMI pedagogy, they significantly impact EMI lecturers’ pedagogic repertoires when implementing interactive assignments. In particular, communication breakdowns between home and international students were explained by poor or non-standard spoken English [12,77,78]. For example, local students expressed frustration about the difficulty of understanding international students’ ‘heavily accented’ English [77]. Conversely, both home and international students encountered difficulties ‘when interacting with native English speakers due to the fast pace of discussion and use of colloquial terms’ [6]. Other students complained that communication was sometimes impossible since the ‘students from the same country always sat together so they could speak their own language’ [79]. Language barriers also seemed to increase in-group pressures noted by students in several studies [73,74,77,78,84,95]. For example, some home students felt that ‘international students might have used their lack of language proficiency as an excuse to seek and receive more help from teachers’ [95].

Another critical issue that students brought forward to express their frustration when studying in culturally mixed groups was multiple and/or unfamiliar accents [6,12,71,77,85,95]. Studying in such environments violated some students’ expectations that ‘in such groups they could learn and speak standard varieties of English such as American or British English’ [77]. When speaking in class it was noted that the accent, stress, intonation, and general English proficiency of some home and international students made it difficult to follow class discussions [6,12,71,85,95]. Some students felt that in such situations lecturers were of little help; thus, students stressed the importance of peer support [78,82,88,95]. For example, some students expressed their willingness to help international students, and often played an important role in bridging the gap between EMI lecturers and international students [95].

Another theme that further highlights the importance of socio-cultural factors is linked to home and international students’ divergent attitudes toward class participation [73,74,84,85,86]. For instance, in one study local students sought to limit their talk in class and would rather wait until after class to talk to the lecturers privately. Such practices were alien to most international students [73], who were often ‘just too active’ and tended to ‘dominate the class discussions’ [74]. Some home students ‘didn’t feel comfortable competing with international students for opportunities to contribute to the discussions’, which led to their gradual withdrawal [74]. Varied cultural and educational backgrounds of students and lecturers in one course had both benefits and challenges for collaborative learning and teamwork [6,78,96,97,98]. According to some students, one of the benefits of diversity on collaborative learning is being ‘freer’ to express one’s opinion ‘because another person’s ideas might be way crazier than yours’ [97]. On the other hand, some students reported difficulties when collaborating with students with different personalities, which manifested itself in ‘frustration over free-riders or a perception that some group members would not pull their weight in completing the required tasks’ [6]. For example, some international students perceived that their higher English proficiency was used in an instrumental way by home students to pressure them to take the lead in finalizing a team project [6].

Finally, one of the important recurring themes within the socio-cultural domain was out-of-class learning, reported in at least eight studies [6,13,53,65,79,81,90,93]. An important aspect of this related to learner autonomy, i.e., the challenges of adapting to what students referred to as an ‘independent learning culture’ at English-medium universities [6]. These students reported being previously more accustomed to close relationships with lecturers and peers, but in the absence of these ‘core sources of information and advice’ they had to cope with day-to-day learning on their own [6,81,93]. Some students stressed that when universities offered a mentoring support, these sessions tended to be rather ineffective [79]. As a result, some students actively sought outside help (e.g., ‘a ladder to climb’ [81]) from former classmates, friends and family members in order to cope with difficulties studying content subject in English [65,81].

4.4. Meta/Cognitive Domain

This domain focuses on themes related to students’ cognitive and metacognitive affordances for EMI content subject learning and comprehension. Findings and quotes from 19 studies (48%) have been synthesised and categorised into six themes. Given the complexity of studying content subjects in L2, students in at least 11 studies (28%) pointed to the problem of processing and comprehension of difficult content. Some students suggested that the concepts were ‘too overwhelming and difficult’ not only for students to learn [79], but even for lecturers to teach [53]. In many studies, students believed that compared with regular classes in L1, taking an EMI course ‘required extra effort, more work and time’ for students [68,69], while during classes ‘keeping up with the teacher and the topic,’ ‘understanding lecture content in English,’ ‘lacking examples to scaffold understanding abstract concepts’, ‘lecturer not explaining the new concept’ or failing to grasp when ‘the lecturer starts a new idea and where they finish it’ [12,75,84] proved stressful and challenging. The most widely used strategy to ‘keep up with the course’ was to use the L1 as much as possible for notetaking, clarifications, cross-checking, and discussions [76].

One of the factors that further complicated the processing of new or difficult concepts was students’ poor background knowledge or schema building [52,53,88,91] especially in the fields of STEM subjects, psychology [52,91], and various research methods. The students’ experiences suggested that lecturers should have taken into consideration not only learners’ prior EMI experiences or English proficiency levels but also their current subject knowledge [88]. On the other hand, when it came to students who had stronger background knowledge and advanced English levels, the problem turned out to be a perceived over-simplification of content by lecturers [74,84,88]. Since lecturers were aware of their own and most students’ problems with English [88], they seemed to have simplified the course delivery and materials, resulting in ‘easy’ and ‘non-challenging’ lectures, discussions, and exams [84]. This sparked frustration and resistance from students with advanced background knowledge and language skills [74,84].

Another hurdle related to this cognitive domain and reported by students was the lecturers’ extensive use of technical language (reported in seven studies). Students complained that when they encountered technical jargon ‘everything became confusing’ and ‘challenging’, partly because ‘they had not learned technical terminology in their English language support classes’ [72,94]. In the absence of support from lecturers, students sought to employ their own strategies, such as guessing from context, regularly using technical dictionaries and Wikipedia, and searching for visual descriptors [12], all of which negatively affected their overall time management and planning for thorough reading of course books or completing other assignments [6,88]. According to students, another barrier to effective comprehension of content was the lack of practical demonstration and/or application of knowledge by content lecturers, as reported in three studies. Since many students seemed to have ‘prioritised disciplinary learning’ [67] ‘acquiring content knowledge and being able to put it into practice’ was the most essential perceived learning outcome [84]. However, according to students, and partly due to lecturers’ language deficiencies or monologic lecturing, practical demonstration or application of course content was not possible, which increased students’ dissatisfaction and disengagement [67,74,84].

Finally, one emerging theme that negatively affected engagement, especially during seminars and discussions, was students’ poor rhetorical and critical thinking skills [6,83,97]. Students pointed to their lack of prior training in criticism and content discussion (e.g., ‘grasping and reflecting on author’s reasoning and proposing alternative methods/perspectives’) during lectures, presentations, team projects, and when writing essays [97]. Some students believed that lecturers’ teaching style by default limited the opportunities for participating in ‘engaged and argumentative’ [6] as well as ‘discussion-centred’ sessions [83].

4.5. Affective Domain

This domain includes themes related to students’ socio-emotional and motivational responses toward EMI. Data from 16 studies (40%) were synthesised and grouped into 10 descriptive themes. Students in at least six studies reported a lack of confidence when taking EMI courses [12,13,52,64,79,82]. Specifically, they felt ‘shameful’ about their poor spoken English, resulting in their avoiding communication with teachers and peers [12,13,52,79]. In some situations, even when students were ‘courageous enough’ to overcome their shyness and participate in discussions, the ‘one-way teaching environment’ undermined such efforts [82]. Although many themes in this domain were closely intertwined, some themes, such as fear of losing face [12,13,64,68,74], were strongly linked to one another. This theme covered situations when students were to interact with native English-speaking lecturers [12,13] and present or speak in front of the class [12,74], as well as with problems of pronunciation [68] and perceived overall ability ‘to get through’ the course [64].

Fear of losing face in the context of communication among students with poor English and their native English-speaking lecturers seemed to negatively affect the building of teacher–student rapport [13,95]. Students expressed their frustration [6,12,64,74,79,95] with having to follow local cultural norms and refrain from disagreeing with faculty [95], or being required to attend courses with poor relevance to their academic majors [74,79], with poor comprehension of content in English, with having to collaborate with other students [6] with lower English proficiency [64], and with lectures being too ‘teacher-centred’ [6]. Although the level of student dissatisfaction with the EMI courses fluctuated from study to study, some articles reported increased dissatisfaction due to linguistic, instructional, and socio-cultural reasons [68,74,79,84,87]. Elevated anxiety and stress were explicitly reported in five studies [6,52,64,68,81] when students felt anxious and stressed at the beginning of the course [81], and when ‘speaking in public’ or answering questions in English [52,68]. Stress levels due to perceived poor English skills were heightened during major summative assessments [64], when reading difficult course materials [6], or when trying to come to terms with lecturers’ strong accents [81]. Some students also reported an increased sense of boredom when lecturers conducted monotonous classes and when topics were either non-challenging or irrelevant to students [12,52,84]. Some students thought that fatigue was ‘a typical state of body and mind’ when attending classes on complex topics in a foreign language [12,52], especially when there was no break [52]. Related to the affective domain, students explained their participation in EMI courses by intrinsic motivation [13,65,66,68,84].

Despite having low levels of English, they sought to attend EMI courses and interact with their teachers and ‘like-minded peers’ [84] as a way ‘to boost their academic learning’ [13], ‘to improve their language skills’ and ‘to maintain the international standards’ [66,68]. They also ‘proactively and creatively developed coping [strategies] that worked for them’ [65]. However, some students’ interest in the course and motivation to learn were negatively affected when lecturers did not demonstrate linguistic fluency and pedagogical competence [66]. Data also pointed to the presence of extrinsic motivation [12,53,68,84] to explain students’ desire to attend EMI courses. In some studies, students believed that EMI experience would better prepare them for future jobs at multinational companies and the growing role of English in the world [12,53,68,84]. In other cases, they took up the courses because of their ‘friends who were enrolled in the same classes,’ ‘because parents insisted’ and due to a perceived need to ‘take an internship abroad and become an Erasmus student’ [68].

4.6. Institutional Domain

This domain includes themes related to university-wide policies and conditions affecting learning in EMI classrooms. Compared to the previous five domains, the institutional needs were less evident in student responses. Eight studies (20%) in total referred to these needs, which were then synthesised and grouped into three themes. Somewhat implicitly, students mention ineffective curriculum design and planning in their universities [74,79,82,87] as affecting the ways in which EMI classes were conducted and classroom experience was affected. Some students stressed that compulsory EMI courses did not take into consideration students’ content needs and language levels, thus increasing disengagement [74,79]. The courses were designed and delivered with the expectation that all students would successfully cope with the linguistic and academic aspects, which often proved incorrect [82]. Some students complained about poor communication channels (often in local languages) regarding the courses offered [79].

Another theme focused on inadequate self-access support [53,82,89,93], i.e., access to facilities and programmes organised by home institutions to help students improve their academic English skills. Some students were ‘critical of the lack, or limited availability’ of support centres or classes [82] and, when available, of the relevance of these to their needs [89]. Although many students were already too overloaded with their EMI classes and assignments to attend additional classes, some students felt the need to attend such programmes improved their composition and spoken English skills [53,93].

Finally, like support centres, some of the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses did not address students’ needs [13,82,89]. For example, some students complained these courses were ‘irrelevant’ and ‘of little value’ because lecturers taught the courses in English in the same way other content classes were taught [13,89], or ‘used methodologies that did not suit the beginners’ [82]. Overall, even from this limited number of studies a strong connection can be seen between institutional policy implementation and classroom experiences.

These findings highlight several crucial factors which might affect the ways in which learner-centred EMI is researched and practiced in the future. This synthesis suggests that the process of adopting learner-centred EMI pedagogy may not be as uniform and standardised as one might to expect.

5. Discussion: Empirical and Pedagogical Implications

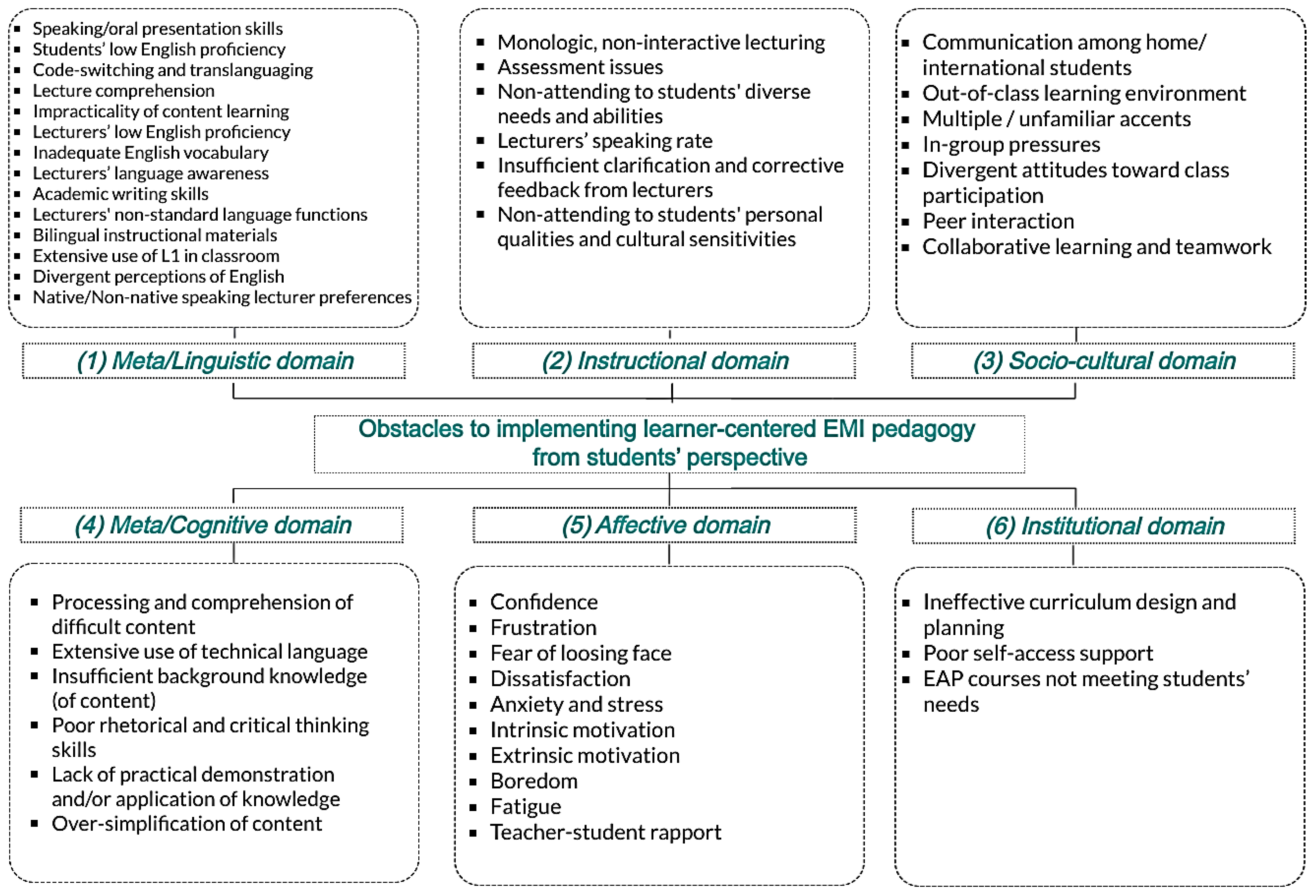

The aim of this study was to identify the challenges to the implementation of learner-centred EMI pedagogy by synthesizing and analysing student experiences as reported in primary qualitative research. The findings reveal that teaching practices and learning environments can create obstacles to promoting learner-centred experiences in the EMI setting. These obstacles are summarised and presented in Figure 6. Five factors are further discussed in this section: (1) context-dependency; (2) multi-dimensionality; (3) domain interdependence; (4) teacher-centredness by default; and (5) sustaining the effectiveness of EMI on all levels.

Figure 6.

Summary schema of analytical domains and descriptive themes.

5.1. Context-Dependency

Perceived obstacles to the implementation of learner-centred pedagogy vary between countries, institutions, disciplines, and teacher and student bodies. For instance, while some studies explained EMI’s ‘dynamism and context dependency’ by reference to institutional factors [29,89], other studies associated it with differences in lecturer profiles (e.g., age, experience, English proficiency, subjects taught, country of residence) and, crucially, access to faculty development and EMI certification [47]. EMI’s context-dependency is reflected especially vividly in the differences among student experiences and perceived challenges across classrooms in different countries and jurisdictions [40,49,50,55,78,96,101]. While researchers stress the importance of ‘context-sensitive ways to implement EMI’ and ‘EMI curriculum innovation’ amidst growing multilingualism in HE [16,89], an important question that remains to be tackled by future research is: whether, in the absence of clear goals and objectives due to the varying contexts, conceptualisations and purposes of EMI among faculty and students, learner-centred pedagogies can be sustainably implemented in diverse EMI classrooms around the world, and if so, how is this to be accomplished?

While answers to this question will depend on the extent and targeted nature of future studies (i.e., by using learner-centred pedagogy as their primary focus, which is scarce in the current EMI literature), we are nonetheless beginning to understand that the high contextuality of EMI is a natural and an inevitable process and not necessarily an impeding issue for EMI’s success. Evidence from the studies synthesised here suggest that every one of the six analytic domains could also be seen as a ‘different context’ and could serve as a blueprint for implementing learner-centred pedagogy along with promoting teacher training, certification, and pre-enrolment support programmes for students [43,46,102].

5.2. Multi-Dimensionality

The six suggested domains are multiple dimensions of EMI pedagogy, which is supported by related studies [7,54,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]. For example, Macaro’s measures of quality interaction in pedagogy place emphasis on the meta-linguistic aspects of interaction (e.g., the use of a wide variety of teacher language functions), while the remaining four measures seem to have been designed as instructional (e.g., extended Initiation–Response–Feedback) as well as (meta)cognitive interventions (e.g., teachers posing questions that require high-level cognitive responses from students, allowing long student turns to help them express higher-level concepts, and giving students sufficient time to allow the thinking process to occur). In addition, lecturer–student and student–student interactions in the EMI context indeed transcend linguistic and metacognitive territories [54,103,104,105,106,110], and may be closely linked to other realms such as the socio-cultural and affective [50,108,109,111,112,113,114]. For example, several studies explored Asian university students’ perceptions of their reluctance in verbal EMI classroom participation, often claiming shyness and poor speaking skills as key determinants [55,115]. It was found that such students used silence as a tool to quietly yet attentively participate and ‘as a way to harmonise with the environment which is the cultural norm’ in their countries [55,115]. Our synthesis reveals that all dimensions related to learner-centred EMI pedagogy might need equal attention, since some are still less well-researched than others. In particular, future studies should examine the impact of socio-cultural, (meta)cognitive, affective, and institutional issues which, according to students, affect their EMI learning experience.

Moreover, most studies thus far have focused on investigating how linguistic and meta-linguistic issues impede student learning in EMI and highlighted the importance of English proficiency for both lecturers and students. This demonstrates how critical the ‘E’ is in successful implementation of learner-centred pedagogical EMI [9,14,44,78,116]. This is echoed by growing research in language comprehension (e.g., how linguistic and metalinguistic ability affects student learning). However, this also means that other factors of the learning environment such as meta/cognitive, instructional, affective, socio-cultural, and institutional factors have been somewhat neglected and need to be studied in much more depth.

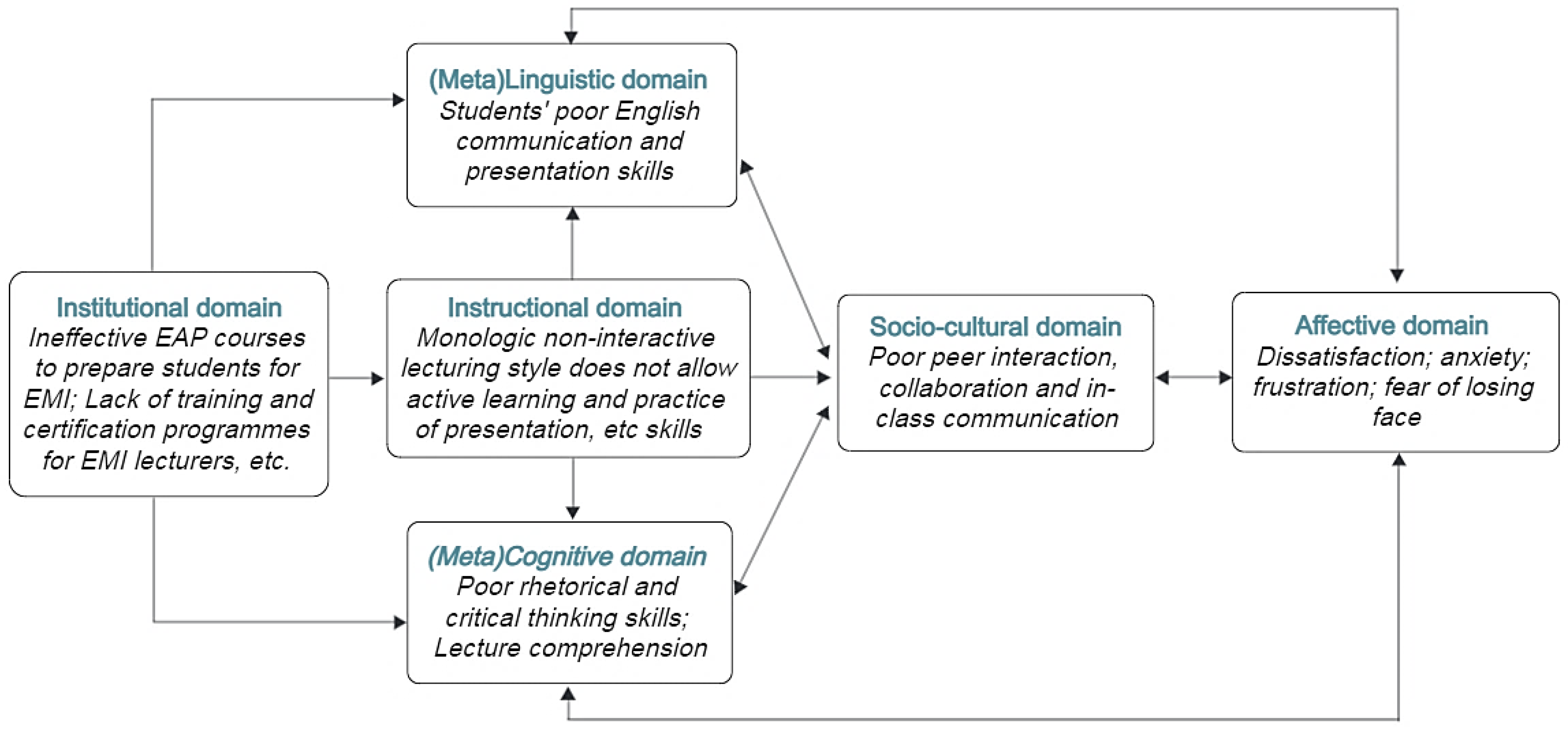

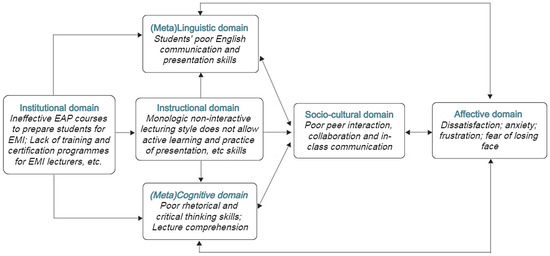

5.3. Domain Interdependence

While our synthesis identified six broad domains, their analysis exposed numerous connections between the domains. Domain interdependence is also evidenced by the quotations from students, which often fitted more than one domain. This indicates that learner-centred EMI pedagogy can be understood as a dynamic web of domains which are closely intertwined and affected by one another; Figure 7 provides a sample schema to support this view. From the diagram, one can see that the socio-cultural and affective domains may well be impacted if the institutional domain has not created adequate conditions to prepare students linguistically and cognitively to enroll in EMI courses or, for the same reasons, not trained lecturers to deliver learner-centred classroom experiences.

Figure 7.

A sample schema of interdependence among domains and themes.

In addition, while observing various ways in which the reviewed studies labelled and classified students’ perceived obstacles to implementing learner-centred pedagogy in EMI, we found that the content of quotations from the different studies were often similar, suggesting that despite varying geographic and institutional contexts [5,51] students often voiced similar experiences and concerns [6,12,64,84,86,87]. This strongly suggests that even under very diverse interpretations of EMI there is something universal in the expectations of learner-centred experiences for students taking EMI content courses.

5.4. Teacher-Centredness by Default

This study found that despite growing awareness in recent years among EMI scholars about the needs and anxieties of students attending EMI courses in HE, in most of the reviewed contexts English Medium Instruction continues to be associated with a teacher-centred learning experience. One possible explanation is that, by default, many EMI lecturers in the selected studies prioritise transmitting content knowledge primarily through monologic lectures, in some cases with limited classroom interaction [12,30,52,53,64,67,79,84]. Participant students in the reviewed studies voiced their concerns with teacher-centred classrooms and the fact that the quality of their learning was evaluated based on their ability to correctly reproduce knowledge provided by teachers [6,65,66,72,78,84,88]. This synthesis has found strong evidence pointing to lecturers’ overuse of didactic modes of teaching and the resulting negative impact on the (meta)cognitive, affective, and socio-cultural aspects of students’ content learning in English.

It is understandable, given the nature of EMI courses with a focus on content delivery rather than language learning and the fears that lecturers have about their own language proficiency, that lecturers may tend to fall back on a monologic approach. Teacher-centred pedagogies have traditionally been associated with formal and hierarchical relationships among lecturers and students [36,117,118], with students perceiving themselves as the ‘consumers’ and lecturers as the ‘providers’ of knowledge [52,53,66,90,91,119,120]. However, it is clear that EMI institutions and lecturers need to find effective solutions in order to integrate learner-centred pedagogy into EMI course design and delivery.

5.5. Sustaining the Effectiveness of EMI on All Levels

Finally, our results have implications for sustaining the effectiveness of EMI on three levels:

- On a micro-level, the success of both HE internationalisation and EMI pedagogy depends on how effectively such programmes can create inclusive environments to sustain students’ learning, motivation, and classroom engagement. As we observed from numerous studies, even ‘small’ issues such as ‘fear of losing face’ or ‘multiple accents in multicultural EMI classrooms’ can impair student learning and satisfaction in the long run when not addressed [13,68,77,95].

- On a meso-level, implementing an effective and learner-centred EMI pedagogy requires a sustainable institutional strategy to train and possibly certify content lecturers. Crucially, such measures could also focus on facilitating collaboration and coordination between content lecturers and language instructors in a systematic manner [3,4,5,6].

- On a macro-level, the success of EMI ultimately depends on how faculty and university administrators perform on the previous two fronts, as they are critical for sustaining international student mobility and inter-university partnerships as strategic objectives of the internationalisation of HE [2].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Overview of Findings

This synthesis has confirmed the findings of previous research in that many students believe in the usefulness of the EMI experience in terms of gaining new content knowledge, enhancing English language skills, and improving the chances of future employment and career growth. The key obstacles to such successful participation can be categorised into many themes, including teacher-centred pedagogical approaches, lack of language awareness by lecturers, and students’ own unpreparedness to effectively participate in EMI courses, among many others. The findings of this synthesis are consistent with previous studies that highlight the critical role of language and academic skills from the perspective of both students and lecturers [9,10,11], as well as the need for dialogic, interactive, and multimodal pedagogical approaches in order to ensure the effective implementation of EMI [7,42,56,121,122].

Consequently, this study has made several important contributions to the literature on EMI. First, by synthesizing qualitative evidence, we have identified six types of challenges for implementing learner-centred EMI pedagogies across diverse geographic and institutional contexts. Second, this study discussed five strategic points which EMI faculty and administrators can use to design effective interventions, improve student satisfaction, and promote the internationalisation of university programmes. Third, the study has found many micro-level pedagogical issues within these six domains, some of which require further research and validation. Finally, this study contains useful implications with regard to sustaining the effectiveness of EMI on three levels in the context of HE internationalisation.

6.2. Strengths and Limitations

An extensive primary qualitative literature search was conducted in order to achieve the study’s goals. In addition, this is the first study to use a systematic thematic synthesis of primary qualitative research to examine students’ views and experiences of EMI. The review process was transparent, systematic, and included empirical studies from a variety of academic subjects and geographies. Furthermore, rigorous article eligibility criteria allowed for stronger internal validity. We thoroughly followed the ENTREQ, CASP and COREQ protocols in conducting this synthesis.

However, since we did not attempt to stratify our findings using various EMI models and typologies such as different purposes of EMI, diverse curriculum models, EMI introduction and access models, etc. [7,28,30], the findings of this study may not be readily applicable to specific EMI contexts. Therefore, future review studies in specific and unique contexts may be warranted. Additionally, while the overall findings from this synthesis are based on insights gathered from a large sample of 1769 university and college students in 20 countries and jurisdictions, the findings from several articles included in this review were themselves limited by small sample sizes [74,78,84,85].

Another limitation of this study is that all 40 studies that met the inclusion criteria were primary qualitative studies (i.e., they used in-depth interviews, classroom observation, focus groups, student journals, and open-ended surveys as their primary data). In doing so, our study has strictly followed the guidelines [63]. However, since the term ‘primary’ remains ill-defined in this context, we excluded papers (N = 61) which used mixed methods even though they featured smaller-scale interviews and focus groups to triangulate their primary quantitative results. Since several previous synthesis studies in other fields have included mixed methods studies [123,124], future EMI synthesis studies might consider adopting a similar approach.

Finally, the samples from the included studies were selected from very diverse student populations, covering both home and international students as well as those studying in undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate and doctoral EMI programmes. Although we recognise that this diversity of respondents and samples may affect the characterisation of challenges for the implementation of learner-centred pedagogy, our aim was to define the commonalities among this diverse population. Therefore, we focused on the content of respondents’ quotations, not their personal characteristics. Given that diverse populations were included in the synthesis, we are convinced that our findings cover a wide range of student views on the challenges in implementing learner-centred EMI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.I.; writing—original draft, M.I.; methodology, M.I., T.K.F.C. and J.D.; data curation, M.I., Y.Y. and N.D.; visualisation, M.I.; software, M.I.; investigation, M.I. and T.K.F.C.; writing—review and editing, M.I., T.K.F.C., J.D. and Y.Y.; project administration, M.I. and Y.Y.; funding acquisition, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research Category C; number 21K00701.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented are available in the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptors of empirical studies included in the synthesis.

Table A1.

Descriptors of empirical studies included in the synthesis.

| # | Author Year [Ref] Document Type | Location | Sample Size, EMI Subject | Design (Data Collection; Data Analysis) | Key Research Question(s) | Quality Appraisal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASP 10-Item Check List [60] | COREQ 32-Item Check List [61] | ||||||

| 1. | Alhassan et al. 2021 [91] Journal article | Sudan | N = 21 Business | Ethnographic research (Semi-structured Interviews, observations, and collection of documents; Content analysis). | What challenges do Sudanese EMI business students experience in EMI courses? To what extent do these problems impact students’ academic performance? | Passed | Passed |

| 2. | Baker & Fang 2020 [98] Journal article | Mainland China (and UK) | N = 45 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (Open-ended questionnaire responses, interviews and focus groups; Thematic framework approach). | To what extent do students develop an awareness of and/or identity as an intercultural citizen because of undertaking EMI programmes in a university abroad? | Passed | Passed |

| 3. | Chalapati et al. 2018 [79] Journal article | Taiwan | N = 64 International tourism and hospitality | A qualitative design (Semi-structured, focus group interviews; Thematic framework approach). | What are the learning experiences of local and international students, and what barriers do they face in an EMI degree programme at a private university? | Passed | Passed |

| 4. | Ding & Stapleton 2016 [81] Journal article | Hong Kong SAR | N = 9 Various EMI courses | A qualitative multiple case study design (semi-structured interviews, classroom observation; Thematic framework approach). | What major problems do students encounter while adapting to the EMI education? | Passed | Passed |

| 5. | Doiz & Lasagabaster 2018 [68] Journal article | Spain | N = 28 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (Focus group interviews and discussions; Thematic framework approach). | How are teachers’ and students’ ideal L2 self-manifested in EMI? What are the teachers’ and students’ reflections on the EMI experience? | Passed | Passed |

| 6. | Doiz et al. 2013 [70] Journal article | Spain | N = 27 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (Focus group discussions; Thematic framework approach). | What does internationalisation mean to the university community? How much does the community value EMI? | Passed | Passed |

| 7. | Fareed et al. 2019 [66] Journal article | Pakistan | N = 104 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (In-depth interviews; Thematic framework approach). | What are the perceptions of school, college and university teachers and students about the medium of instruction? | Passed | Passed |

| 8. | Galloway & Ruegg 2020 [89] Journal article | Japan and Mainland China | N = 29 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (Open-ended questionnaire responses, interviews and focus groups; Thematic framework approach). | What are the core principles of EMI? How can students studying through the medium of English be supported? What are the needs of the international student body? | Passed | Passed |

| 9. | Hamid et al. 2013 [76] Journal article | Bangladesh | N = 54 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (semi-structured interviews, classroom observations; Inductive content analysis). | How do teachers and students develop language practices, ideologies and institutional othering in a private university in Bangladesh? | Passed | Passed |

| 10. | Han et al. 2020 [95] Journal article | Mainland China | N = 25 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (In-depth interviews; Thematic framework approach). | What challenges do local students experience when working with international students? | Passed | Passed |

| 11. | He & Chiang 2016 [86] Journal article | Mainland China | N = 60 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (Open ended reports; Thematic framework approach). | English-medium education aims in accommodating international students in Mainland Chinese universities, and how well are they working? | Passed | N/A (No interviews/focus groups used) |

| 12. | Henry & Goddard 2015 [69] Journal article | Sweden | N = 32 Various EMI courses | A qualitative discourse analysis (Semi-structured interviews; Discursive analysis). | Does identity play a role in explaining Swedish students’ enrolment in an EMI programme? | Passed | Passed |

| 13. | Hino 2017 [85] Book chapter | Japan | N = 4 Various EMI courses | A qualitative interpretive design (Case studies, class observation, class video recording, open-ended questionnaire; Content analysis). | How could EMI help students acquire communicative abilities in EIL, including linguistic, sociolinguistic, and interactive? | Passed | N/A (No interviews/focus groups used) |

| 14. | Holi Ali 2020 [65] Journal article | Oman | N = 12 Engineering | A qualitative interpretive design (Semi-structured interviews; Inductive content analysis). | How did Omani engineering students respond to EMI challenges? | Passed | Passed |

| 15. | Hua 2020 [52] Journal article | Taiwan | N = 30 Psychology | A qualitative interpretive design (Qualitative open-ended questionnaire and focus group discussions; Content analysis). | What are the factors facilitating or hindering local students’ EMI learning? What are their suggestions to facilitate EMI experiences? | Passed | Passed |