Participation of Local People in the Payment for Forest Environmental Services Program: A Case Study in Central Vietnam

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

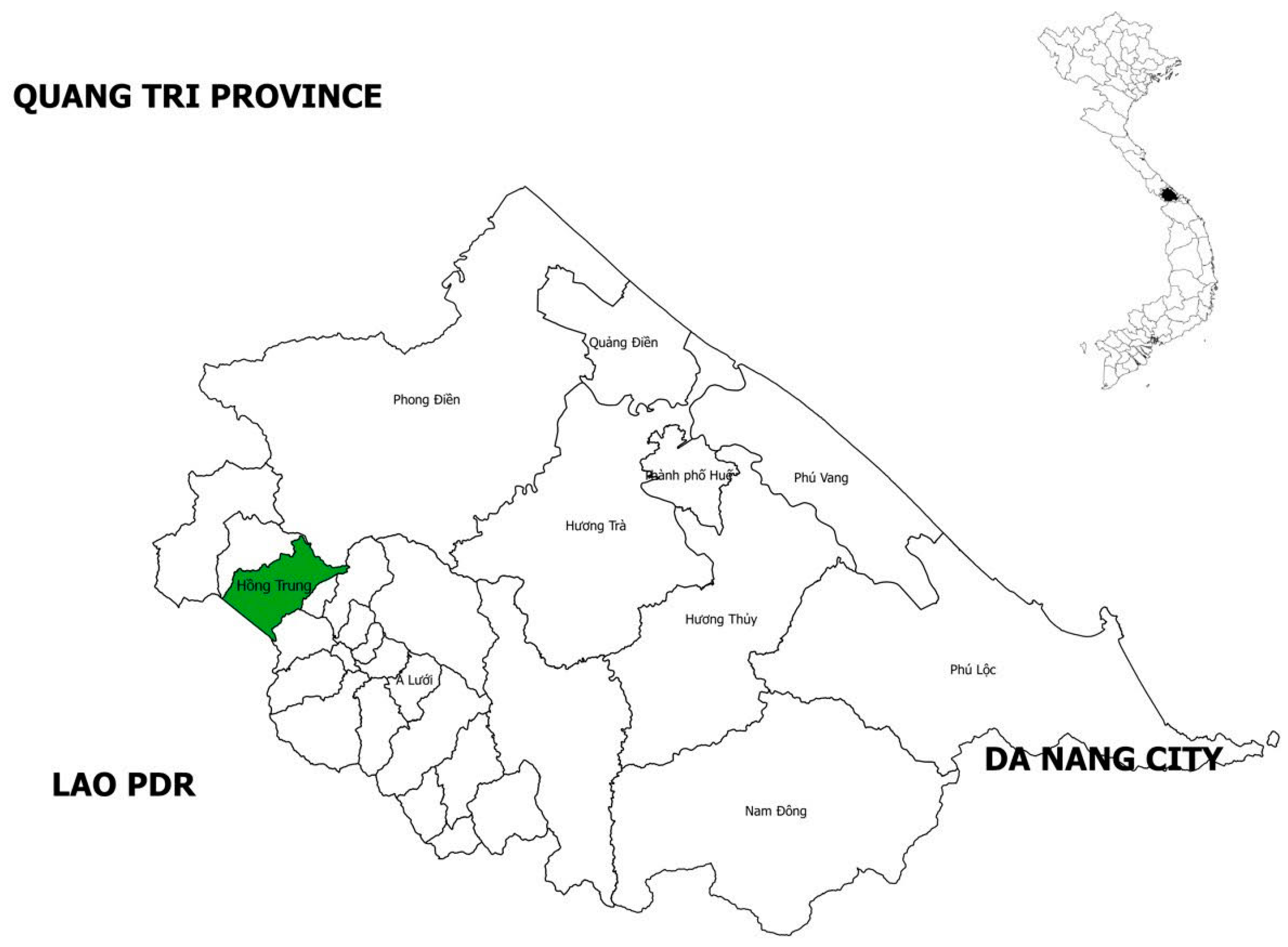

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Who Are the Participants?

3.2. Level of Participation

3.3. Impacts of PFES on Local People

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wegner, G.I. Payments for ecosystem services (PES): A flexible, participatory, and integrated approach for improved conservation and equity outcomes. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 18, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagiola, S.; Arcenas, A.; Platais, G. Can Payments for Environmental Services Help Reduce Poverty? An Exploration of the Issues and the Evidence to Date from Latin America. World Dev. 2005, 33, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balvanera, P.; Uriarte, M.; Almeida-Leñero, L.; Altesor, A.; DeClerck, F.; Gardner, T.; Hall, J.; Lara, A.; Laterra, P.; Peña-Claros, M.; et al. Ecosystem services research in Latin America: The state of the art. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P.; Nghiem, T.; Le, H.; Vu, H.; Tran, N. Payments for environmental services and contested neoliberalisation in developing countries: A case study from Vietnam. J. Rural. Stud. 2014, 36, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Corbera, E.; Pascual, U.; Kosoy, N.; May, P. Reconciling theory and practice: An alternative conceptual framework for understanding payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Arsel, M.; Pellegrini, L.; Adaman, F.; Aguilar, B.; Agarwal, B.; Corbera, E.; De Blas, D.E.; Farley, J.; Froger, G.; et al. Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wunder, S. When payments for environmental services will work for conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, N.; Martinez-Tuna, M.; Muradian, R.; Martinez-Alier, J. Payments for environmental services in watersheds: Insights from a comparative study of three cases in Central America. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts; CIFOR: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vatn, A. An institutional analysis of payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden, S.; Lee, D.R. Paying for Environmental Services: An Analysis of Participation in Costa Rica’s PSA Program. World Dev. 2005, 33, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, M.A.; Westby, L. Community participation in payment for ecosystem services design and implementation: An example from Trinidad. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieg-Gran, M.; Porras, I.; Wunder, S. How can market mechanisms for forest environmental services help the poor? Preliminary lessons from Latin America. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1511–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. No pay, no care? A case study exploring motivations for participation in payments for ecosystem services in Uganda. Oryx 2012, 46, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corbera, E.; Brown, K.; Adger, W.N. The Equity and Legitimacy of Markets for Ecosystem Services. Dev. Chang. 2007, 38, 587–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M.; Shivakoti, G.P. Multi-level Forest Governance in Asia: An introduction. In Multi-Level Forest Governance in Asia: Concepts, Challenges and the Way Forward; Inoue, M., Shivakoti, G.P., Eds.; SAGE: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, U.; Muradian, R.; Rodríguez, L.C.; Duraiappah, A. Exploring the links between equity and efficiency in payments for environmental services: A conceptual approach. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M. A participatory framework for conservation payments. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, N.; Corbera, E.; Brown, K. Participation in payments for ecosystem services: Case studies from the Lacandon rainforest, Mexico. Geoforum 2008, 39, 2073–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T. The allocation of forestry land in Vietnam: Did it cause the expansion of forests in the northwest? For. Policy Econ. 2001, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, P.X.; Tran, N.H.; Zagt, R. Forest Land Allocation in Viet Nam: Implementation Processes and Results. Tropenbos Int. Vietnam 2013, 2013, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Meyfroidt, P.; Lambin, E.F. Forest transition in Vietnam and its environmental impacts. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008, 14, 1319–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.; Bennett, K.; Vu, T.; Brunner, J.; Le, N.; Nguyen, D. Payments for Forest Environmental Services in Vietnam: From Policy to Practice; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2013; ISBN 9786021504109. Available online: https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/OccPapers/OP-93.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- To, P.; Dressler, W. Rethinking ‘Success’: The politics of payment for forest ecosystem services in Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.H.; Zeller, M.; Suhardiman, D. Payments for ecosystem services in Hoa Binh province, Vietnam: An institutional analysis. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, H.P.B.; Fujiwara, T.; Iwanaga, S.; Sato, N. Challenges of the Payment for Forest Environmental Services (PFES) program in forest conservation: A case study in Central Vietnam. J. For. Res. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, S.; Yokoyama, S.; Duong, D.T.; Van Minh, N. Policy effects for forest conservation and local livelihood improvements in Vietnam: A case study on Bach Ma National Park. J. For. Res. 2019, 24, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loft, L.; Le, D.N.; Pham, T.T.; Yang, A.L.; Tjajadi, J.S.; Wong, G.Y. Whose Equity Matters? National to Local Equity Perceptions in Vietnam’s Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services Scheme. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 135, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual Report: Thua Thien Hue Forest Protection Department 2019; Thua Thien Hue Department of Agriculture and Rural Development: Thua Thien Hue, Vietnam, 2019.

- Pham, T.; Nguyen, T.; Dao, C.; Hoang, L.; Pham, L.; Nguyen, L.; Tran, B. Impacts of Payment for Forest Environmental Services in Cat Tien National Park. Forests 2021, 12, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, P.T.; Chau, N.H.; Chi, D.T.L.; Long, H.T.; Fisher, M.R. The politics of numbers and additionality governing the national Payment for Forest Environmental Services scheme in Vietnam: A case study from Son La province. For. Soc. 2020, 4, 379–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Exploring equity and sustainable development in the new carbon economy. Clim. Policy 2003, 3, S41–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, C.Y.; Corbera, E. Participation dynamics and institutional change in the Scolel Té carbon forestry project, Chiapas, Mexico. Geoforum 2015, 59, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, N.T.; De Groot, W.T. The impact of payment for forest environmental services (PFES) on community-level forest management in Vietnam. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 113, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.K.; Rahman, G.M.; Fujiwara, T.; Sato, N. People’s participation in forest conservation and livelihoods improvement: Experience from a forestry project in Bangladesh. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2012, 9, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, T.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Impact of payments for environmental services and protected areas on local livelihoods and forest conservation in northern Cambodia. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 29, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bremer, L.L.; Farley, K.A.; Lopez-Carr, D.; Romero, J. Conservation and livelihood outcomes of payment for ecosystem services in the Ecuadorian Andes: What is the potential for ‘win–win’? Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 8, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wealth Rank | Household Member | Household Head | Labor Force | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Education | ||||||||

| Category | N | Av. | SD. | Av. | SD. | Av. | SD. | Av. | SD. |

| Poor | 13 | 4.32 | 1.11 | 40.06 | 12.08 | 3.51 | 1.48 | 2.64 | 1.11 |

| Non-Poor | 19 | 4.24 | 1.11 | 40.48 | 12.01 | 3.45 | 1.46 | 2.65 | 1.09 |

| Total | 32 | 4.28 | 1.11 | 40.38 | 12.02 | 3.53 | 1.49 | 2.66 | 1.09 |

| Poor | Non-Poor | |

|---|---|---|

| PFES participation | 9 (69.2%) | 13 (68.4%) |

| Form of participation | Community (9) | Community (9), Local organization (4) |

| Reasons | Poor | Non-Poor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentages | Number | Percentages | |

| Increasing income | 11 | 84.6 | 15 | 78.9 |

| Protecting community forest | 7 | 53.8 | 12 | 63.1 |

| Collecting NTFPs | 3 | 23.1 | 2 | 10.5 |

| Stability of payment | 9 | 69.2 | 9 | 47.3 |

| Others | 4 | 30.8 | 5 | 26.3 |

| Activities | Poor (N = 9) | Non-Poor (N = 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Forest patrolling | 88.9% | 84.6% |

| Making forest boundaries | 33.3% | 38.5% |

| Forest fire fighting | 33.3% | 46.1% |

| Measuring biomass | 11.1% | 23.1% |

| Participation in training | 55.6% | 69.2% |

| Attending meetings | 66.7% | 76.9% |

| Before PFES | Under PFES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Non-Poor | Poor | Non-Poor | |

| Land use classification | ||||

| Residential areas (%) | 5.70 | 4.43 | 5.69 | 4.31 |

| Agricultural land (%) | 6.72 | 7.73 | 7.01 | 7.53 |

| Mean agricultural land (ha) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Forestland (%) | 87.58 | 87.84 | 87.30 | 88.16 |

| Mean forestland (ha) | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 1.09 |

| Legality | ||||

| Land use certification (%) | 56.70 | 57.00 | 59.20 | 60.70 |

| Without land use certification (%) | 43.30 | 43.00 | 40.80 | 39.30 |

| Household Income | Poor (13) | Non-Poor (19) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFES (9) | Without PFES (4) | PFES (13) | Without PFES (6) | |

| Total (Million VND) | 23.3 | 22.3 | 26.8 | 24.2 |

| Purpose | Poor (9) | Non-Poor (13) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hhs | Percentage | Number of hhs | Percentage | |

| Savings | - | - | 2 | 15.3% |

| Agricultural investment | - | - | 3 | 23.1% |

| Payment of bills | 1 | 11.1% | 3 | 23.1% |

| Purchase of forest patrolling equipment | 2 | 22.2% | 4 | 30.8% |

| Payment of children education fees | 3 | 33.3% | 2 | 15.3% |

| Payment of debts | 4 | 36% | 2 | 15.3% |

| Purchase of necessities | 6 | 66.7% | 10 | 77.4% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngoc, H.P.B.; Fujiwara, T.; Iwanaga, S.; Sato, N. Participation of Local People in the Payment for Forest Environmental Services Program: A Case Study in Central Vietnam. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212731

Ngoc HPB, Fujiwara T, Iwanaga S, Sato N. Participation of Local People in the Payment for Forest Environmental Services Program: A Case Study in Central Vietnam. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212731

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgoc, Hoang Phan Bich, Takahiro Fujiwara, Seiji Iwanaga, and Noriko Sato. 2021. "Participation of Local People in the Payment for Forest Environmental Services Program: A Case Study in Central Vietnam" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212731

APA StyleNgoc, H. P. B., Fujiwara, T., Iwanaga, S., & Sato, N. (2021). Participation of Local People in the Payment for Forest Environmental Services Program: A Case Study in Central Vietnam. Sustainability, 13(22), 12731. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212731