1. Introduction

Payments for ecosystem/environmental services (PES) have emerged internationally as the new environmental conservation concept over the past two decades. Since PES were defined by Wunder in 2005 [

1], discussions of the concept [

2,

3,

4,

5] and evaluation of specific cases [

6,

7,

8] have taken place globally. These international discussions have been led mainly by environmental economists.

While the development of scholarly definitions of PES is a recent phenomenon, Japan has a centuries-long history of using various forms of these payments. Efforts to require downstream villages to bear the cost of protecting upstream water source forests have been reported since at least the late 17th century [

9], nearly 200 years before the establishment of the modern land ownership system in Japan. Since then, systems in which downstream organizations pay for the conservation of upstream forests have developed in various forms across Japan. In general, these efforts have been referred to as downstream “participation (参加)” or upstream–downstream “interaction (交流)” for water source forest conservation. These expressions focus on broader cooperative relationships between regions rather than purely economic relationships.

With the growing international interest in PES, a recently developed system in Japan known as the Forest Environmental Tax has been described as a PES-like scheme by some authors [

10,

11,

12]. It has also been pointed out that the scheme deviates to some extent from the “ideal” PES proposed by environmental economists [

12], because it was not designed purely for the application of market mechanisms. However, this scheme did not appear out of nowhere in Japan, as it includes aspects that have developed over hundreds of years of experience [

13,

14]. Japanese PES-like schemes, including Forest Environmental Tax systems, can be understood as solutions to interregional problems involving forest ecosystem services that have been agreed upon and accepted by the society. The deviation from the “ideal” PES represents the presence of a different logic and perspective than that held by environmental economists, in the solution that was developed over time in Japan.

This paper aims to consider the significance of PES with cooperative relationships, by examining the historically formed solutions in Japan. In

Section 2, we review the theory of PES as presented in international discussions, as well as the discourse on PES-like systems in Japan. In

Section 3, we apply this discussion to Japan to identify the characteristics and historical evolution of typical PES-like systems there. Then, in

Section 4, we clarify the key attributes of the Japanese perspective on PES, which emphasize building solidarity across regions. Finally, in

Section 5, we discuss the significance of the Japanese perspective on PES.

2. Theoretical Discussion of PES and PES-like Systems

2.1. PES Theory in International Discussions

The concept of PES has spread widely in international discussions since the 2000s. PES is recognized as an innovative paradigm that evolved in response to the command-and-control approach, such as the designation of protected areas, which spread in the 1960s, 1970s, and late 1980s, and the integrated approach to conservation and development, which spread in the 1990s [

1,

15]. The PES concept is described as being different from these conventional conservation paradigms [

1,

15]. Compared to the integrated approach, PES schemes are described as direct approaches with specific aims that are cost-effective; compared to the command-and-control approach, PES are voluntary, negotiated frameworks [

1].

However, the definition of PES is debatable, as two perspectives provide different scopes for the concept [

2,

3]. The environmental economics perspective provides a narrow definition of PES focusing on efficiency [

1,

5,

16]. The ecological economics perspective is broader and includes social aspects [

4,

17]. The former is considered mainstream [

4], and many efforts have been made to evaluate actual examples of PES-like initiatives with reference to the “true PES” from the environmental economics perspective [

7,

12]. The most widespread definition of PES is the one by Wunder, i.e., “a voluntary transaction where a well-defined ecosystem service is being ‘bought’ by an ecosystem service buyer from an ecosystem service provider if and only if the ecosystem service provider secures ecosystem service provision” [

1] (p. 3), which was modified by himself in 2015 to “voluntary transactions between service users and service providers that are conditional on agreed rules of natural resource management for generating offsite services” [

5] (p. 241). Most of the actual cases, including the Japanese Forest Environmental Tax system, do not meet the narrow requirements of this perspective’s definition of a “true PES”.

This narrow definition “mirrors the functioning of an ideal PES type” [

5] (p. 235). The “ideal” PES is basically derived from the Coase Theorem and emphasizes market mechanisms and efficiency [

1,

16]. The relationship between the user, who pays for ecosystem services, and the provider, who receives the payment in exchange for these services, occurs within the market. The business-like relationship [

1] between the two parties is regarded as the most innovative feature of PES. Wunder described the transaction through this relationship as one that “without pretending to hold community hands—it is all about selling and buying a service to achieve a more rational land use” [

1] (p. 7). The relationship assumed between the two parties here is arms-length and without emotion.

In contrast to this mainstream PES perspective, authors from the ecological economics perspective focus more on actual practices than the ideal model and consider the complexity of the real world. They regard the market as only one type of coordination mechanism [

4,

17]. Vatn pointed out that, in addition to markets, there are two other systems that connect users and providers: hierarchy and community management [

17]. He noted that these three systems typically coexist in actual PES practices, despite many viewing PES as belonging only to the market system. While market-focused solutions strengthen the forces separating the parties, Vatn emphasized the need for PES to strengthen cooperative will. Here, we find a view of the relationship between the parties that contrasts Wunder’s view.

2.2. Theoretical Discussion on PES-like Systems in Japan

A generation before these international debates on PES heated up, Kumazaki provided a theoretical analysis of the systems for upstream water source forest conservation with downstream payments, developed in Japan [

18]. These systems were taken as examples of the negotiations among the affected parties described by Coase. The means of internalizing external economies include taxation, subsidy policies, direct regulation, and inter-party negotiations. Among these, Kumazaki highlighted that inter-party negotiations are considered an appropriate means of finding a solution, especially in cases where services are provided to a limited geographical area, such as watershed forest conservation, as the affected parties know most about their interests [

18].

Moreover, Kumazaki argued that these systems result from political and administrative processes based on the consensus of both sides, and are supported by a sense of regional solidarity [

18]. Such solidarity and communication among people is explained as being necessary to reconcile conflicts using Rawls’ principles [

19] of defining the scope of one’s activities in terms of others and thinking in terms of the other person being in the worst condition. The solidarity emphasized here is a strong example of cooperative will, as noted by Vatn [

17], and the opposite of the emotionless and distant relationship assumed by Wunder [

1].

The theoretical work of Kumazaki was carried out in parallel with detailed fact-finding surveys of the natural and socioeconomic conditions in major watersheds in Japan. Between 1974 and 1981, a group of researchers, including Kumazaki, published a considerable number of reports [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Additionally, Kumazaki compiled and summarized centuries of examples from around Japan, in which downstream organizations “participated” in the conservation of upstream watershed forests by sharing the costs [

9,

30,

31]. This was the period when the most intensive research on payments for water source forest conservation was conducted in Japan.

Kumazaki did not specify an ideal model of negotiations or provide an evaluation of existing cases in comparison to the ideal status. This is because his discussion was intended to provide a theoretical framework of possible options for those considering the implementation of different systems. He assumed that there were limits to what could be explained by economic theory and that value judgments and decision-making were essentially left to the people involved [

18,

32]. The structures of the systems that were established should be respected as the solution achieved by the parties at each time.

2.3. Viewing PES from a Perspective of Relationship Building

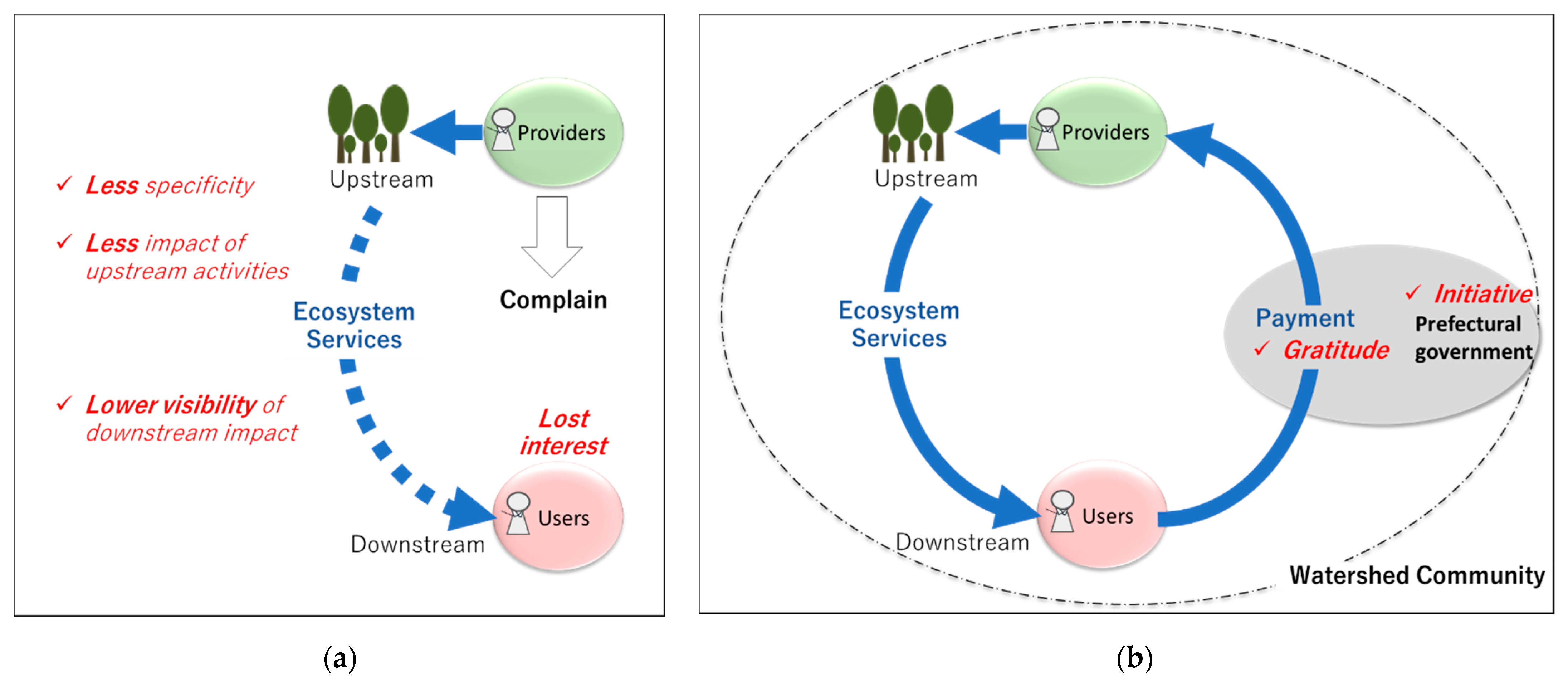

The key element dividing the two PES perspectives discussed above is how the relationship between the two parties, users and providers, is understood. In the following section, we will clarify the relationship between users and providers in PES-like practices in Japan, focusing on three aspects: (1) the conditions of the ecosystem services, (2) the interests of providers and users, and (3) the characteristics of the payment as a means of connecting the two parties (see

Figure 1).

Regarding the conditions of ecosystem services, site specificity of the ecosystem services and the degree of dependence of each party on these services are crucial factors affecting the relationship between the two parties. The strength of the linkage between the two parties depends on which ecosystem service requires payment. For services with limited target areas, such as watershed forest conservation, a higher level of coordination, rather than competition, is generally required [

33]. On the other hand, in the case of payments for services that are not necessarily land-limited in scope, such as carbon sequestration [

4] or cross-border payments [

17], a higher degree of commodification of transactions is more likely to occur. The distance required between the two parties also depends on the mechanism that connects them [

17].

The intensity of provider and user interests in ecosystem services fundamentally reflects the extent of each party’s awareness of its dependence on those services. Natural disasters provide an opportunity for people to become more aware of their dependence on ecosystem services, but the development of disaster management facilities may diminish this awareness. It is also important to note that the objects of interest among service providers and users are not necessarily limited to environmental services and the amount of payment; moreover, what the provider or user is interested in will affect the meaning of the payment.

The meaning of payment is a crucial issue that divides the understanding of PES. Payment is often perceived as a mere economic relationship, but it is embedded in the wider social context [

17]. The perceptions of payment by the participants are not purely instrumental perceptions that follow individual interests, but often follow the logic of reciprocity; in other words, payments are perceived as a way to maintain social relationships [

17]. The word “participation” is commonly used to describe payments for water source forest conservation in Japan. This implies great awareness of social relations that go beyond mere economic relations. After examining downstream payments in Japan, Furuido noted that if payments cultivate a sense of participation among water users, then the payments are considered to be an important positive measure [

34].

Questions such as who took the initiative and who was able to reflect their will on the payment—decide whether or not to pay, how much to pay, how to use the amount paid, and how to monitor it—and to what extent, are important both from the standpoint of advocating the importance of negotiations between parties who know the actual situation well [

18] and that voluntariness is an innovative element of PES [

1]. The position of the government, which often plays an important role in payment systems, needs to be carefully considered. Governments are generally viewed as third parties who are neither users nor providers [

17,

35], and government-funded programs are generally considered to be compulsory for users [

35]. However, the government sometimes acts as a water-user group. There are various forms of the relationship between the government and individual residents, and the fact that the government takes the initiative does not necessarily mean that the will of the residents is not reflected at all.

Considering the above factors, the relationship between providers and users of environmental services as assumed in Wunder’s discussion [

1] can be illustrated as in

Figure 2.

3. Experiences of Downstream Payments for Upstream Forests in Japan

3.1. Methodology

To clarify the relationship between users and providers of PES-like practices in Japan, we identify three phases in which the nature of the relationship between the two parties differs and examine each of them. The first two of the three phases—”the initial form of downstream payments” and “the spread of regional cooperation led by prefectures”—were extracted from numerous case studies presented by Kumazaki [

9,

30,

31], focusing on the differences in the relationships. The third phase, “Forest Environmental Tax system as a tool to arouse public interest by payment,” has developed in recently and shows a different relationship to the previous two phases.

For cases in which the characteristics of each phase are observed, we used published reports, records, and secondary literature to understand the relationship between users and providers, and identify the implication of the payments.

3.2. Initial Forms of Downstream Payments

3.2.1. Cases

Coping with natural disasters is an integral part of life in Japan. The land is covered by steep and complex mountainous terrain, with heavy precipitation, short and steep gradient rivers, occurrences of earthquakes, and volcanoes. These characteristics make residents vulnerable to mountain-related disasters. In particular, for paddy rice farmers, sufficient and stable water supplies are critical [

9]. As with many countries in Asia [

7], a high population density also intensifies conflicts over land use. For these reasons, people living downstream from forests frequently have strong interests in their condition.

The earliest documented example of payment from downstream villages in Japan was in the late 17th century [

9]. This was a period of widespread coping with the decrease and degradation of forests due to population growth and new rice field development [

36,

37]. In 1684, the clan, the feudal authority that ruled the area, made a decision as an arbitrator that 23 downstream villages would pay rice as salaries for the forest rangers in the water source forests that were planted after the drought [

38,

39]. Another recorded case occurred in the late 18th century, involving a conflict between an upstream village that planned to cut down trees for charcoal production and downstream villages that were concerned about destabilizing the water supply. The case was settled by the downstream villages paying a lump sum of money and annual rice payments in exchange for the upstream villages’ termination of logging [

9].

Beginning at the end of the 19th century, the installation of modern water supply systems caused downstream cities to take a keen interest in the forests in upstream areas. The city of Yokohama, for example, was concerned about the devastation of the forests in the watershed area and began to take various measures. The city paid compensation to the owners of the mines, leading the latter to give up their mining rights [

30]. In the early 20th century, the city of Yokohama purchased upstream forests after an upstream village successfully opposed the designation of the area as a protected forest for more than a decade. As a condition of this purchase, various compensatory measures were offered to the upstream village, such as sharing profits from timber sales and preferential employment. For more than 100 years since then, the city of Yokohama has managed the water source forests as well as maintained its relationship with the upstream village.

3.2.2. Relationship between Users and Providers

Figure 3 illustrates a typical relationship between the upstream village and the downstream party in this phase. Downstream payments were one of the solutions reached after negotiations between the upstream and downstream parties that occurred in response to the risk of crises. The target forests in which the downstream side was interested were generally limited, and their needs for the conditions of the area were critical. On the other hand, for the upstream side, the utilization of the target forest was an important livelihood issue. Compromise between the two parties, both of which were strongly affected by the same forest, included a means of payment from the downstream party. Both sides participated in the negotiations by necessity.

These payments for the conservation of watershed forests play a significant role in reconciling the opposition of the upstream community to conservation measures. The conditions imposed on people living upstream as ecosystem service providers often include the waiver of some rights to the watershed forest, but the conditions vary in form. Downstream residents desperately need these conditions, and when they are not met, conflicts often flare up, leading to further negotiations.

Payments for upstream forest protection were established as a complement rather than an alternative to protected forests. The designation of a forest as a protected area by the government was a means of securing the solution. It was not necessarily imposed unilaterally by the government; it could also serve as a means for the villages involved to ensure that both parties were in agreement.

3.3. Spread of Regional Cooperation Initiated by Prefectures

3.3.1. Cases

From the early 20th century to the mid-late 20th century, payments for watershed forest conservation shifted from downstream initiatives to upstream initiatives [

31]. While public investment by the government increased dramatically after a period of high economic growth in the mid-20th century, downstream communities rapidly lost interest in the upstream forests. Dams and other construction between upstream and downstream cities had disconnected their direct relationships. Mountains were covered with forest, and the forests transitioned from the planting phase to the growing phase in the 1970s. The link between disaster prevention and forests has become less visible over time. On the other hand, many of the villages in upstream areas suffered from depopulation, and some mountain villages were displaced by the creation of reservoirs behind new dams. The residents of mountain villages were gradually becoming dissatisfied with prosperous cities that had forgotten the forests upstream.

In this context, relatively large-scale funds for watershed forest conservation were established, led by prefectures. The case of Kiso-sansen is one of the most symbolic examples. The governor of Gifu Prefecture, which has the watershed areas of three major rivers (Kiso-sansen) in its jurisdiction, planned to improve the watershed forests in the late 1960s in order to recover from water pollution caused by overcutting and forest deterioration caused by natural disasters [

31,

40,

41]. In addition to allocating its own budget for this purpose, the prefecture requested expenditure from downstream entities such as Aichi Prefecture, Nagoya City, and electric power companies. The governor of Aichi Prefecture showed strong interest in the project and cooperated as a promoter. Later, the governor of Aichi Prefecture also established two funds for the conservation of water source forests in smaller water basins that were located within the prefecture [

31,

42]. In addition, Fukuoka Prefecture, together with municipalities in the prefecture, established a large fund for the conservation of forests in the watershed after a severe drought in 1978 [

31,

43].

In contrast, the Forestry Agency unsuccessfully attempted to establish a tax based on water use [

44]. From 1985 to 1986, the Forestry Agency, together with politicians (Diet members—government representatives) and forestry organizations, proposed to establish a water source tax that would be levied on citizens and industries in proportion to the amount of their water use and would be used for the maintenance of water source forests. Based on examples of prefectural initiatives and the results of research on downstream cost-sharing, vigorous efforts were made. However, due to strong opposition from the industrial sector, the proposal was not implemented.

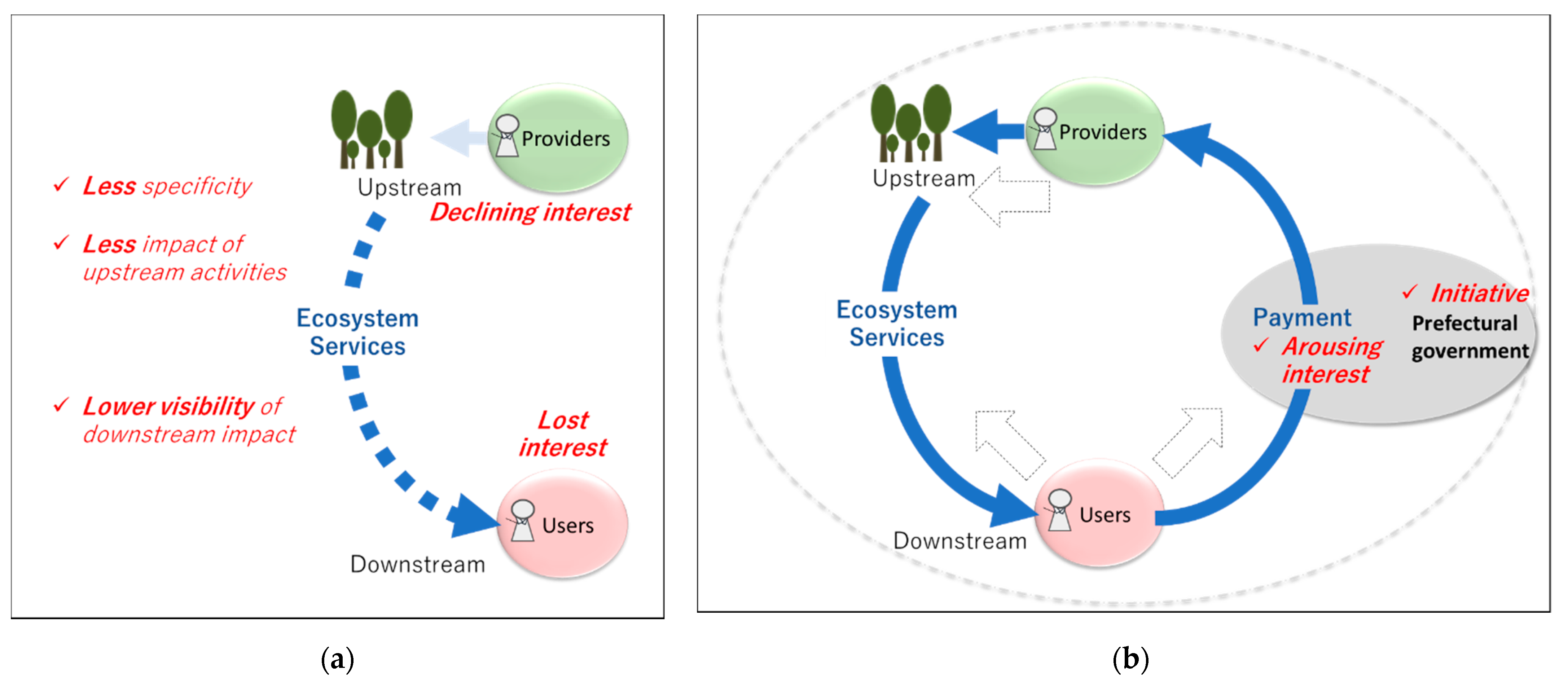

3.3.2. Relationship between Users and Provider

The upstream–downstream relationship in these prefecture initiatives, such as Watershed Funds, is illustrated in

Figure 4. The distinctive feature here is that the prefectural government has taken the initiative in establishing the payment system by taking into account the situation and intentions of both upstream and downstream parties.

Why were the prefectures able to establish cost-sharing systems that could not be implemented by the national government? The main reason for this was the decision to not adopt a method of taxation based on the amount of water usage, as we will see later. However, the leadership of the governors was also one of the key reasons for success. Prefectures in Japan often have jurisdiction over the entire watershed, while municipalities generally have jurisdiction over only parts of the watershed, such as the upstream or downstream area. In such cases, the prefectures have both upstream and downstream interests in consideration. This makes it easier for the prefectures to decide to pay for the forests in the upstream area with funds collected mainly from the downstream area. On the other hand, it makes it difficult for individual residents to be aware of their payments. In the case of the Kiso-sansen, a partnership was established between the prefecture with the upstream forests and the prefecture with the downstream cities. However, the two prefectures each had both upstream and downstream or midstream interests within their territory, and cooperation was established, led by governors [

31,

40,

41].

The statements of the governors leading the movement in the prefectures emphasized solidarity in the region. In Fukuoka prefecture, the fund establishment resulted from complaints of upstream forest managers that downstream communities benefiting from the watershed forests they had nurtured had not expressed gratitude to the upstream communities [

43]. The governor of Fukuoka Prefecture explained that the fund was intended to express gratitude to the upstream communities [

31]. In the case of the Kiso-sansen, the governor of the downstream Aichi Prefecture had a strong interest in building a cross-border cooperative relationship and was proactive in conserving the watershed forests through joint efforts of multiple prefectures [

31,

40]. The governor of Aichi Prefecture at the time emphasized the importance of having a spirit of cooperation between people upstream and downstream for the development of the watershed as a whole rather than focusing on profit or loss [

31,

42]. When the fund was established, it was the upstream municipalities that were in a particularly difficult position, as they wanted to emphasize the importance of watershed forest conservation, but were concerned about their communities’ decline due to dam construction. In their speeches, the governors emphasized the importance of building a relationship between upstream and downstream communities. This spirit of cooperation was often indicated using the phrase “watershed community” [

42,

45].

The payment systems were introduced with the intention of expressing gratitude and empathy from the downstream communities to the upstream communities, while the physical and psychological division between the upstream and downstream communities due to dams and other factors spread. Compared to the initial form, discussed previously in

Section 3.2, an inevitable need to secure PES services diminished, and the prefectural government, which had both upstream and downstream interests, made an executive decision to institute payments for upstream watershed forests. On the other hand, individual prefectural residents, especially those downstream, had little opportunity to hear about the intention of the governor to establish the fund and were frequently unaware of the system [

46]. The solidarity as a “watershed community” was built mainly through executive decisions.

3.4. Forest Environmental Tax System as a Tool to Arouse Public Interest by Payment

3.4.1. Cases

One of the most controversial issues with the water source tax proposal in the 1980s was that the financial burden was based on the amount of water used [

44], which differed from the prefectural initiatives at the time. This was the primary cause of the industrial opposition that prevented the proposal from being implemented. In the 1990s, however, a couple of cases emerged in which the payment systems were based on the amount of water usage [

13]. One was established by Kanagawa Prefecture, though the payment was borne only by some residents of the prefecture. Two others were established by cities. In all cases, payment systems were established in response to droughts. Both cities were already participating in the above-mentioned “watershed community” in their region, and the new payments expanded the measures for watershed conservation. Although the number of cases of implementation were limited, this system was expected to raise awareness for participation in forest conservation in the watershed through the act of paying the water bill [

47]. Meanwhile, with the expansion of local governments’ tax autonomy due to the amendment of laws for decentralization in 2000, the momentum for the establishment of a water source tax system grew among prefectures. Kochi Prefecture, with its many forests and small population, and Kanagawa Prefecture, with its many large cities, were among the first to respond.

In Kochi Prefecture, the governor announced the establishment of a tax for forest conservation, and studies were conducted to examine possible systems to be introduced. The tax was provisionally called the “Watershed Conservation Tax”; it was intended that water users would bear the cost [

48]. After discussions with experts and various exchanges of opinions with the people of the prefecture, a new tax system called the “Forest Environmental Tax” was established in Kochi Prefecture in 2004. The adopted system charged each resident a fixed amount of money rather than an amount proportionate to water usage. Following Kochi, subsequent prefectures established similar taxes. However, Kanagawa Prefecture had already imposed a fee for watershed forest conservation based on the amount of water use on a limited number of users; the prefectural government had spent five years discussing the possibility of taxation linked to water use. In 2007, Kanagawa Prefecture created a system that included taxation based on income, which was thought to affect the amount of water use. As of 2021, these kinds of tax systems, collectively known as the Forest Environmental Tax, have been introduced in 37 out of 47 prefectures.

3.4.2. Relationship between Users and Provider

Figure 5 shows the relationship between upstream and downstream communities in the Forest Environmental Tax system initiated by prefectures. By raising the issue of additional taxation, the prefectural government intends to stimulate public interest in forests and to build a conscious collaborative relationship across regions through forest policy.

The Forest Environmental Tax systems are similar to the prefectural initiatives described previously in

Section 3.3, in that the prefectures, which have both upstream and downstream areas, build systems by taking into account the interests of both parties. The most distinctive feature of the Forest Environmental Tax system, on the other hand, is that the prefectural governments attempted to arouse the interest of a wide range of prefectural residents in the payments by asking whether additional taxation should be imposed. The question of the necessity of additional tax is salient and can draw the attention of the public, and elucidate whether they are interested in forests. In fact, in the two prefectures leading the Forest Environmental Tax initiative, various forms of intense discussions and gathering of opinions took place before establishing the tax system. It is a payment system that focuses on raising individual users’ awareness for the importance of forest conservation and to bear the cost for it. The Forest Environmental Tax system has become known as a “participatory tax system” [

49,

50,

51,

52]. This concept emphasizes the significance of citizens’ participation in the entire process, from the consideration of whether or not to introduce a tax to the verification of how the tax is used. This was a new concept that emerged in the process of considering the tax.

Another interesting feature of the Forest Environmental Tax compared to earlier cases of prefectural initiatives is that prefectures with large forests and small populations, such as Kochi Prefecture, attempted to introduce it ahead of others. Focusing on these natural and socioeconomic conditions, Kochi Prefecture can be regarded as a prefecture with relatively “upstream interests” in the whole of Japan. The governor of Kochi Prefecture, who used additional taxes to stimulate residents’ awareness of and participation in forest conservation, intended to disseminate information about the efforts started there to the rest of Japan. Looking at the interest of Kochi Prefecture in Japan as a whole, it was also a way to allow prefectures with large forests (upstream prefectures) to appeal to those with large populations (downstream prefectures). At that time, there was a debate over the reduction of fiscal transfers to less populated areas in the country, and there were several movements among the less populated prefectures that asserted the significance of having forests with diverse and important values [

53]. The creation of a Forest Environmental Tax can be seen as one of these movements.

After the Forest Environmental Tax systems spread to many prefectures, the national government introduced the Forest Environment Transfer Tax in 2019. Under this scheme, the national government allocates a certain amount of tax revenue to municipalities and prefectures based on their forest area, population size, and number of forestry workers. Every municipality, including those with no forests in their jurisdictions, is required to use the transferred tax revenue to implement forest environment conservation measures. By increasing taxes, this measure did not stimulate debate as the prefectural Forest Environmental Tax did, but instead used the allocated tax to focus the attention of municipalities on forest conservation.

4. The Japanese Perspective of Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services

In the previous section, we have described the characteristics of typical PES cases that have spread in Japan in each phase, focusing on the relationship between service providers and users. These typical cases in Japan have the following features when compared to “ideal” PES. PES in upstream forests were a means of communication across regions and not merely a demonstration of monetary value. Payment provided a means to understand mutual connections instead of an arms-length transaction without personal feelings. The efforts have focused on enabling downstream people to understand and empathize with upstream conditions rather than pursuing a scientific basis or economic rationale for payment.

The core concept in understanding payments for forest ecosystem services in Japan is interregional solidarity. Looking back on Japanese history, there has always been a strong emphasis on building cooperative relationships between upstream and downstream communities. This likely reflects the natural and socioeconomic conditions of Japan. That is, the interrelationship between upstream and downstream communities is relatively clear and close because of the steep stream gradient and shortness of rivers. The interest in water sources is relatively high because river water is widely used as drinking water. Additionally, the contrast in socioeconomic conditions between upstream communities, where forestry is relatively more important economically and depopulation is occurring, and downstream communities, which are urban and densely populated, is relatively clear. Even in communities with such different social and economic backgrounds and little direct interaction between people, PES has been seen as a way for people to feel a sense of solidarity in living together and to feel a sense of connection across regions.

The nature of this relationship of solidarity between upstream and downstream communities, however, has changed over the years. The solidarity in the initial forms of downstream payments arose inevitably from a strong dependence on forest ecosystem services in upstream areas. The payments were a kind of conciliation to convince upstream communities of downstream demand for upstream forests. As the impact of upstream forest services became less visible, the government built solidarity artificially through payments. The payments gradually shifted from having a socio-economic meaning, the sharing of the upstream burden, to having a psychological meaning, the expression of gratitude and awareness of dependency.

The greater role of the government did not necessarily mean a weaker reflection of individual will. Rather, the government sought to substantiate the sense of solidarity by making individual users more aware of the meaning of payment. In the past few decades, the main purpose of payments for forest ecosystem services in Japan has been to raise awareness among people.

The Japanese perspective on payment is difficult to explain in terms of economic rationality in the short run. This indicates how building solidarity among regions is regarded as an essential issue in Japan and how payments for forest ecosystem services are expected to enable it. As connections among communities become less and less visible, societies increasingly need forest ecosystem services to make people aware of cross-regional connections.

5. Conclusions

In this article, we examined the nature of the PES with cooperative relationships, that evolved over centuries of history in Japan. The sense of solidarity that Kumazaki once saw as supporting negotiations between parties to internalize the external economy through payments [

18] has now become the very purpose of payments in Japan. Payments for forest ecosystem services are now a way to deliver messages of solidarity across regions.

There are two aspects to the meaning of payment: the expression of a quantity of value and the statement of a qualitative message. While environmental economists refer to the “ideal PES” as focusing on the former aspect to achieve efficient and inexpensive trade, Japanese PES-like practices, on the other hand, focus on the latter aspect to build stable and cooperative relationships across the region, and even throughout the country. The Japanese cases are intended to create an opportunity to think about the qualitative meanings of the payment, which is emphasizing the importance of forest ecosystem services and expressing gratitude for their supply, by asking whether the amount of burden is acceptable, and to connect this to building relationships of solidarity. It can be seen as a way to send a qualitative message by means of a quantitative expression.

This type of PES in Japan may not be as innovative as environmental economists suggest, but it is doubtless a direct and democratic exchange of messages between the parties involved and encompasses a kind of voluntariness in that users can reflect a certain degree of their will by participating in discussions about payment. However, the primary significance of cooperative PES may not lie in this directness and voluntariness. Rather, we can find its significance in the fact that payments can be a way to approach the issue of building solidarity among groups with conflicting interests by focusing on the function of payments as messengers, which has often been overlooked in the past.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.I. and S.M.; writing—original draft, R.I.; writing—review and editing, R.I. and S.M.; supervision R.I.; visualization, R.I. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number JP18H03422).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yasuto Hori for his comments on the draft and Hiromichi Furuido for sharing with us materials on PES-like cases in Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts. CIFOR Occas. Pap. 2005, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Farley, J.; Costanza, R. Payments for Ecosystem Services: From Local to Global. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2060–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, L. Redefining Payments for Environmental Services. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 73, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Corbera, E.; Pascual, U.; Kosoy, N.; May, P.H. Reconciling Theory and Practice: An Alternative Conceptual Framework for Understanding Payments for Environmental Services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the Concept of Payments for Environmental Services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosoy, N.; Martinez-Tuna, M.; Muradian, R.; Martinez-Alier, J. Payments for Environmental Services in Watersheds: Insights from a Comparative Study of Three Cases in Central America. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 61, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Upadhyaya, S.K.; Jindal, R.; Kerr, J. Payments for Watershed Services in Asia: A Review of Current Initiatives. J. Sustain. For. 2009, 28, 551–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine-De-Blas, D.; Wunder, S.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.; Del Pilar Moreno-Sanchez, R. Global Patterns in the Implementation of Payments for Environmental Services. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumazaki, M. Progress of Water-shed Forests Establishment by the Down-stream Parties Concerned (I) (水源林造成における下流参加の系譜 (I): 費用分担問題への接近). Water Sci. 1981, 25, 1–24. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Ito, H. Payments for Ecosystem Services (生態系サービスへの支払い (PES)). In Basic Knowledge of Biodiversity, Ecosystems and Economics (生物多様性・生態系と経済の基礎知識); Hayashi, K., Ed.; Chuohoki Publishing CO., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2010; pp. 172–192. ISBN 978-4-8058-4912-5. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y. Issues of Forest Environmental Tax and Water Resources Fund from the Viewpoint of PES—Focusing on the Case Study of Aichi Prefecture (PESの視点から見た森林環境税及び水源基金の課題: 愛知県の事例検討を中心に). J. Water Environ. Issues 2015, 28, 75–81. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Tanaka, K. Models Explaining the Levels of Forest Environmental Taxes and Other PES Schemes in Japan. Forests 2021, 12, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, R. Forest Environmental Taxes in the Progress of the Measures for Forest Conservation (水源林保全における費用負担の系譜からみた森林環境税). Water Sci. 2010, 54, 46–65. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaki, R. Benefit and cost sharing in the Forest-environment-tax system (森林環境税における受益と負担). Environ. Inf. Sci. 2019, 48, 43–48. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Muradian, R. Cognitive framing, collective action and ecosystem services. In Les Services écosys- témiques dans les espaces agricoles. Paroles de chercheur(e)s, 2nd ed.; Métaprogramme Inra EcoServ, Ed.; Métaprogramme Inra EcoServ: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 13, pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing Payments for Environmental Services in Theory and Practice: An Overview of the Issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A. An Institutional Analysis of Payments for Environmental Services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazaki, M. Forest Utilization and Environmental Conservation: Basic Principles of Forest Policy (森林の利用と環境保全: 森林政策の基礎理念); Kumazaki, M., Ed.; Japan Forest Technology Association: Tokyo, Japan, 1977. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- The Forestry Agency Planning Division. Research Report on Establishment of Cost Sharing Relationship for Forestation and Its Maintenance Summary: The Tone Valley (森林造成維持費用分担関係設定調査報告書要旨: 利根川流域); The Forestry Agency Planning Division, Ed.; The Forestry Agency Planning Division: Tokyo, Japan, 1975; (In Japanese).

- The Forestry Agency Planning Division. The Forestry Agency Planning Division Report on Promotion of Cost Sharing for Forestation and Its Maintenance (森林造成維持費用分担の推進について); The Forestry Agency Planning Division, Ed.; The Forestry Agency Planning Division: Tokyo, Japan, 1976; (In Japanese).

- The Forestry Agency. Research Report on Promotion of Cost Sharing for Forestation and Its Maintenance: The Shinano Valley (森林造成維持費用分担推進調査報告書: 信濃川流域); The Forestry Agency, Ed.; The Forestry Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 1977; (In Japanese).

- The Forestry Agency. Research Report on Promotion of Cost Sharing for Forestation and Its Maintenance: The Yoshino Valley (森林造成維持費用分担推進調査報告書: 吉野川流域); The Forestry Agency, Ed.; The Forestry Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 1978; (In Japanese).

- The Forestry Agency. Research Report on Promotion of Cost Sharing for Forestation and Its Maintenance: The Kumano Valley (森林造成維持費用分担推進調査報告書: 熊野川流域); The Forestry Agency, Ed.; The Forestry Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 1979; (In Japanese).

- The Forestry Agency. Report on the Implementation of the Cost Sharing of Forestation and Its Maintenance (森林造成維持費用分担実施報告書); The Forestry Agency, Ed.; The Forestry Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 1981; (In Japanese).

- The Forestry Agency Planning Division. Project for Promotion of Cost Sharing for Forestation and Its Maintenance: Supplementary Explanation Material No.2 Overview by Watershed (森林造成・維持費用分担推進事業 附帯説明資料 その2 流域別概況); The Forestry Agency Planning Division, Ed.; The Forestry Agency Planning Division: Tokyo, Japan, 1974; (In Japanese).

- Water Science Institute. Research Report on Establishment of Cost Sharing Relationship for Forestation and Its Maintenance: The Tone Valley (森林造成維持費用分担関係設定調査報告書 利根川流域); Water Science Institute, Ed.; Water Science Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 1975. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Water Science Institute. Research Report on Promotion of Cost Sharing for Forestation and Its Maintenance; The Chikugo Valley (森林造成維持費用分担推進調査報告書筑後川流域); Water Science Institute, Ed.; Water Science Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 1976. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Water Science Institute. Research Report on Establishment of Cost Sharing Relationship for Forestation and Its Maintenance; The Kiso Sansen Valley (森林造成維持費用分担関係設定調査報告書 木曽三川流域); Water Science Institute, Ed.; Water Science Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 1976. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kumazaki, M. Progress of Water-shed Forests Establishment by the Down-stream Parties Concernd (II) (水源林造成における下流参加の系譜 (II): 費用分担問題への接近). Water Sci. 1981, 25, 32–55. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazaki, M. Progress of Water-shed Forests Establishment by the Down-stream Parties Concerned (III) (水源林造成における下流参加の系譜(III): 費用分担問題への接近). Water Sci. 1981, 25, 33–54. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazaki, M. A Study on Forest Planning (I)—Forest Resource Use and Environmental Problems: An Economic Analysis- (森林利用計画に関する研究 (第I報)-森林資源利用と環境問題; その経済分析-). Bull. Gov. For. Exp. Stn. 1974, 262, 1–40. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Landell-Mills, N.; Porras, I.T. Silver Bullet or Fools’ Gold: A Global Review of Markets for Forest Environmental Services and Their Impact on the Poor; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Furuido, H. The Cost Allocation of the Forest Watersheds Improvement (流域管理と費用負担). For. Econ. 1993, 46, 8–15. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Engel, S.; Pagiola, S. Taking Stock: A Comparative Analysis of Payments for Environmental Services Programs in Developed and Developing Countries. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, K. Transformation of the Land and Focus on Water and Soil Conservation (国土の変貌と水土保全への着目). In Edo Studies of Forests II (森林の江戸学II); The Tokugawa Institute for the History of Forestry, Ed.; Tokyodo Shuppan Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 8–19. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T. Edo and Meji Era Trial of Peasants in Mountain Dispute (江戸・明治 百姓たちの山争い裁判); Soshisya: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Endoh, Y. Japanese Forest History; Protected Forests Vol.1 (日本山林史 保護林篇上); Japan Mountain Forest History Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1934. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- The Forestry Agency. The Forestry Agency A Compendium of the Forest System in the Tokugawa Era (徳川時代に於ける林野制度の大要); The Forestry Agency, Ed.; Forestry Mutual Aid Association: Tokyo, Japan, 1954; (In Japanese).

- Tsutsui, M. Current Status and Problems of the Kiso-Sansen River Water Source Development Public Corporation—Particularly the Reality of the Cost Burden in Downstream Areas (木曽三川水源造成公社の現状と問題点: 特に下流地域の費用負担の実状). For. Conserv. 1975, 2, 57–76. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Horibe, Y. Forest and Downstream Water Use Issues: A Case of the Kiso-sansen River Water Source Development Corporation (森林と下流の水利用の問題: 木曽三川水源造成公社の場合). For. Technol. 1973, 380, 5–7. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui, M. One Way of Beneficiary Sharing of the Cost of Water Source Forest Maintenance: A Study on the Establishment of the “Water Source Fund System” in Aichi Prefecture (水源林整備費用の受益負担の一方式: 愛知県の「水源基金制度」の設立経緯を通しての考察). For. Conserv. 1980, 9, 16–42. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka Prefecture Water Source Forest Fund. Ten Years of History (10年のあゆみ); Fukuoka Prefecture Water Source Forest Fund: Fukuoka, Japan, 1988. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Council of Forest Management and Prevention. A Record of the Campaign to Establish a Water Resources Tax and Forest and River Tax: Using This Ordeal as a Springboard for the Creation of Lush Forests (水源税, 森林河川整備税創設運動の記録: この試練を糧として, 緑豊かな森林づくりを); Council of Forest Management and Prevention: Fukuoka, Japan, 1987; (In Japanese).

- Kitagawa, M. Establishment of the “Water Source Fund” and Its Implementation in Aichi Prefecture (愛知県における ‘水源基金’ の設立と事業の実施状況). For. Technol. 1980, 459, 11–14. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Kojima, M. Current Status and Issues of Water Source Forest Development under the Fund System: A Case Study of the Toyokawa Water Source Fund (基金方式による水源林整備の現状と課題-豊川水源基金を事例として). Trans. Mtg. Chubu Br. Jpn. For. Soc. 1989, 37, 83–87. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, T. Verification of the Forest Conservation System from the Viewpoint of Beneficiary Burden Theory: Using the Toyota City Water Source Conservation Fund as a Case Study (受益者負担論からみた森林保全制度の検証: 豊田市水道水源保全基金を素材にして). Water Sci. 2005, 285, 48–85. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, M. Forest Environmental Tax in Kochi Prefecture—Significance and Role (高知県の森林環境税について: その意義と役割). In Sustainable Societies and Local Government Finance (持続可能な社会と地方財政); Japan Association of Local Public Finance, Ed.; Keiso Shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; pp. 85–109. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Morotomi, T. Basis and design of the Forest Environmental Tax (森林環境税の課税根拠と制度設計). In Institutional Design for a Decentralised Society (分権型社会の制度設計); Japan Association of Local Public Finance, Ed.; Keiso Shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2005; pp. 65–81. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Morotomi, T. Consideration of a Water Resources Tax and Forest Environmental Tax Beyond the Existing Basis of Taxation (水源税・森林環境税の検討 既存の課税根拠を超えて). Mon. Jichiken 2005, 554, 46–53. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ueta, K. Environmental Asset Management and Participatory Taxation (環境資産マネジメントと参加型税制). Local Taxes 2003, 54, 2–5. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ueta, K. Environmental Assets, Local Economy, Participatory Taxation (環境資産 地域経済 参加型税制). In Participatory Taxation, Kanagawa’s Challenge—Environment and Taxation in the Age of Decentralisation (参加型税制 かながわの挑戦: 分権時代の環境と税); CONTEXT Ltd., Ed.; Dai-Ichi Hoki Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2003; pp. 179–185. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki, R. Forest Improvement Measures and Public Investment by Prefectures (都道府県による森林整備施策と公共投資). In Sustainable Societies and Local Government Finance (持続可能な社会と地方財政); Japan Association of Local Public Finance, Ed.; Keiso Shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; pp. 49–68. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).