Construct Dimensionality of Personal Energy at Work and Its Relationship with Health, Absenteeism and Productivity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

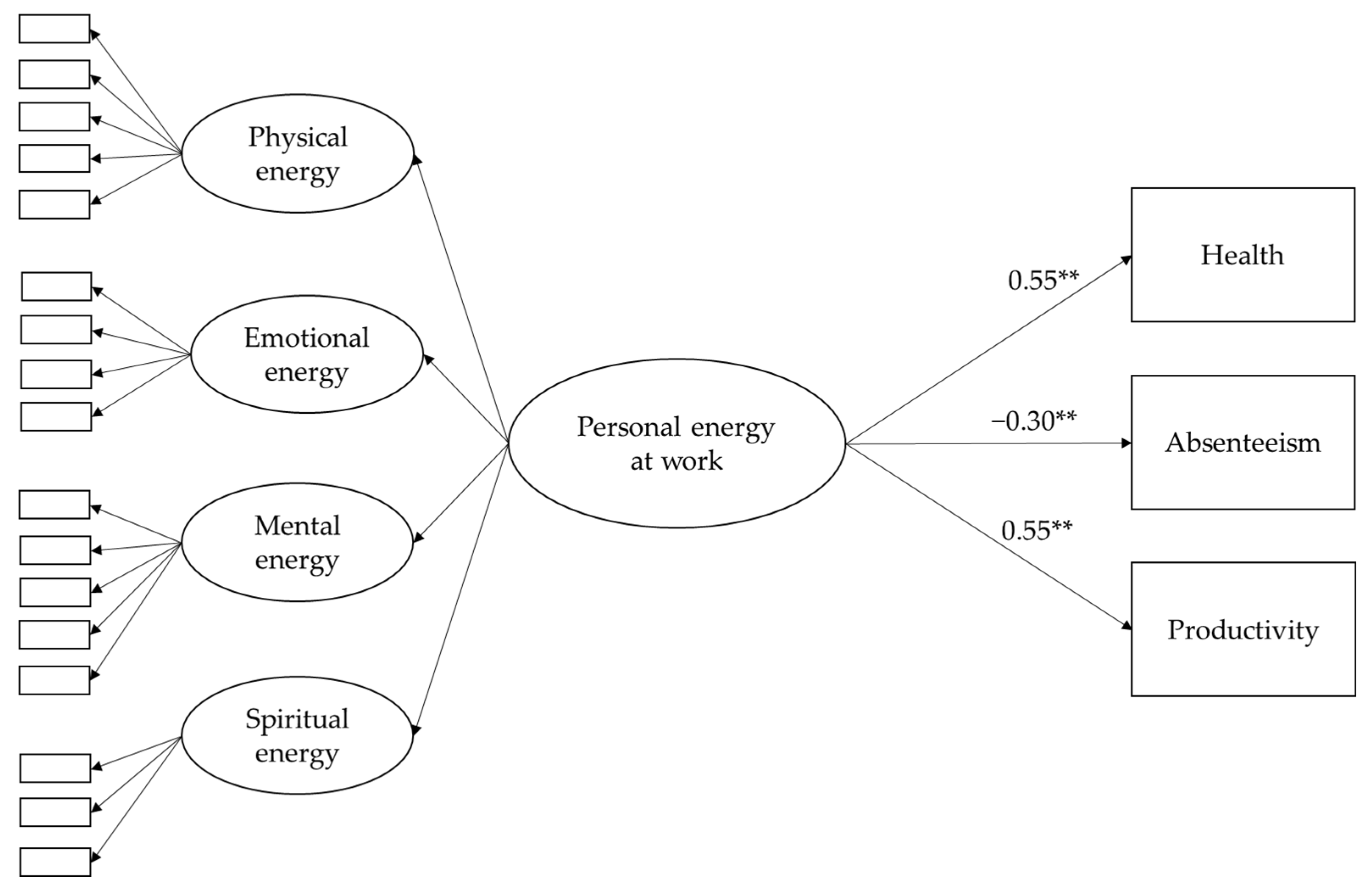

2.1. The Four Dimensions of Personal Energy at Work

2.2. The Relationship between Personal Energy at Work and Health/Productivity Outcomes

3. Materials & Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analyses

4.2. Descriptives

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. The Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Limitation and Recommendations for Future Research

5.3. Practical Implication

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable. | Question |

|---|---|

| Energy Physical | A feeling of vitality |

| Energy Physical | I feel I have physical strength |

| Energy Physical | I feel energetic |

| Energy Physical | I feel full of pep (energy, vigor, liveliness, spirit) |

| Energy Physical | I feel vigorous (strong, healthy, full of energy) |

| Energy Emotional | I feel capable of being sympathetic to coworkers and customers |

| Energy Emotional | I feel I am capable of investing emotionally in coworkers and customers |

| Energy Emotional | I feel able to show warmth to others |

| Energy Emotional | I feel able to be sensitive to the needs of coworkers and customers |

| Energy Mental | A feeling of flow (the mental state of fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity) |

| Energy Mental | I feel mentally alert |

| Energy Mental | I feel able to be creative |

| Energy Mental | I feel I can think rapidly |

| Energy Mental | I feel I am able to contribute new ideas |

| Energy Spiritual | I believe that my life has purpose |

| Energy Spiritual | I work toward long-term goals in my life |

| Energy Spiritual | I am aware of what is important to me in life |

| Productivity | Over the last 3 months, roughly how productive have you felt in your job? |

| Health | Over the last 3 months, how would you rate your overall health? |

| Absenteeism | Over the last 3 months, how many working days have you been off work through illness or injury? |

| Descriptives | What is your age? |

| Descriptives | What is your gender? |

| Descriptives | What country do you work in? |

| Descriptives | What is the highest level of education you have completed? |

| Descriptives | How many hours a week do you work on average? |

| Descriptives | For how many years have you been employed within Philips? |

| Descriptives | For how many years have you been employed in total (all work employers together)? |

| Descriptives | Do you have a managerial position (direct reports)? |

References

- de Jonge, J.; Peeters, M. The Vital Worker: Towards Sustainable Performance at Work. IJERPH 2019, 16, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niessen, C.; Maeder, I.; Stride, C.; Jimmieson, N.L. Thriving When Exhausted: The Role of Perceived Transformational Leadership. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 103, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Porath, C. Creating Sustainable Performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- van Scheppingen, A.R.; de Vroome, E.M.M.; ten Have, K.C.J.M.; Zwetsloot, G.I.J.M.; Bos, E.H.; van Mechelen, W. Motivations for Health and Their Associations With Lifestyle, Work Style, Health, Vitality, and Employee Productivity. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 56, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abid, G.; Ijaz, S.; Butt, T.; Farooqi, S.; Rehmat, M. Impact of Perceived Internal Respect on Flourishing: A Sequential Mediation of Organizational Identification and Energy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1507276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabe, D.P.; Melnyk, B.M.; Buck, J.; Sinnott, L.T. Effects of the Nurse Athlete Program on the Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors, Physical Health, and Mental Well-Being of New Graduate Nurses. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2017, 41, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human Resource Management and Employee Well-Being: Towards a New Analytic Framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schieman, S.; Badawy, P.J.; Milkie, M.A.; Bierman, A. Work-Life Conflict During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Socius 2021, 7, 2378023120982856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of Working From Home During COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users. J. Occup. Environ. Med 2021, 63, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Lam, C.F.; Spreitzer, G.M. It’s the Little Things That Matter: An Examination of Knowledge Workers’ Energy Management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 26, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pluta, A.; Rudawska, A. Holistic Approach to Human Resources and Organizational Acceleration. J. OrgChange Mgmt 2016, 29, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.W.; Spreitzer, G.M.; Lam, C.F. Building a Sustainable Model of Human Energy in Organizations: Exploring the Critical Role of Resources. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2012, 6, 337–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehr, J.; Schwartz, T. The Making of a Corporate Athlete. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2001, 79, 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-Being. J. Personal. 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Coenen, P.; Howie, E.; Lee, J.; Williamson, A.; Straker, L. A Detailed Description of the Short-Term Musculoskeletal and Cognitive Effects of Prolonged Standing for Office Computer Work. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A. Feeling Vigorous at Work? The Construct of Vigor and the Study of Positive Affect in Organizations. In Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive Intervention Strategies; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 135–164. ISBN 978-0-7623-1057-9. [Google Scholar]

- Both-Nwabuwe, J.M.C.; Dijkstra, M.T.M.; Beersma, B. Sweeping the Floor or Putting a Man on the Moon: How to Define and Measure Meaningful Work. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Fry, L.W. The Role of Spiritual Leadership in Reducing Healthcare Worker Burnout. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2018, 15, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.M.; Miller, J.A.; Bostock, S. Helping Employees Sleep Well: Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Work Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingson, L.D.; Kuffel, A.E.; Vack, N.J.; Cook, D.B. Active and Sedentary Behaviors Influence Feelings of Energy and Fatigue in Women. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Wahlqvist, P.; Shikiar, R.; Shih, Y.-C.T. A Review of Self-Report Instruments Measuring Health-Related Work Productivity: A Patient-Reported Outcomes Perspective. Pharm. 2004, 22, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C.; Sonnentag, S.; Sach, F. Thriving at Work-A Diary Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 468–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T.D.; Kiburz, K.M. Trait Mindfulness and Work–Family Balance among Working Parents: The Mediating Effects of Vitality and Sleep Quality. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Canby, N.K.; Cameron, I.M.; Calhoun, A.T.; Buchanan, G.M. A Brief Mindfulness Intervention for Healthy College Students and Its Effects on Psychological Distress, Self-Control, Meta-Mood, and Subjective Vitality. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.; Özcan, N.A.; Babal, R.A. The Mediating Role of Thriving: Mindfulness and Contextual Performance among Turkish Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D.; Marshall, I. Spiritual Intelligence: The Ultimate Intelligence; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7475-3644-4. [Google Scholar]

- Loehr, J.; Schwartz, T. The Power of Full Engagement: Managing Energy, Not Time, Is the Key to High Performance and Renewal; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Strecher, V.J.; Ryff, C.D. Purpose in Life and Use of Preventive Health Care Services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16331–16336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fawcett, S.E.; Brau, J.C.; Rhoads, G.K.; Whitlark, D.; Fawcett, A.M. Spirituality and Organizational Culture: Cultivating the ABCs of an Inspiring Workplace. Int. J. Public Adm. 2008, 31, 420–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Shirom, A. Conservation of Resources Theory: Applications to Stress and Management in the Workplace. In Handbook of Organization Behavior; Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 2, pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, A.; Toker, S.; Schachler, V.; Ziegler, M. The Effect of Change in Supervisor Support and Job Control on Change in Vigor: Differential Relationships for Immigrant and Native Employees in Israel: Supervisor Support, Job Control, and Vigor. J. Organiz. Behav. 2017, 38, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wefald, A.J.; Smith, M.R.; Gopalan, N.; Downey, R.G. Workplace Vigor as a Distinct Positive Organizational Behavior Construct: Evaluating the Construct Validity of the Shirom-Melamed Vigor Measure (SMVM). Empl. Respons. Rights J. 2017, 29, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.S.; Awais, A. Effects of Leader-Member Exchange, Interpersonal Relationship, Individual Feeling of Energy and Creative Work Involvement towards Turnover Intention: A Path Analysis Using Structural Equation Modeling. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 21, 99–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armon, G.; Shirom, A. The Across-Time Associations of the Five-Factor Model of Personality with Vigor and Its Facets Using the Bifactor Model. J. Personal. Assess. 2011, 93, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Song, Y.; Xiao, X.; Shi, W. The Effect of Social Capital on Tacit Knowledge-Sharing Intention: The Mediating Role of Employee Vigor. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020945722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewster, C.; Houldsworth, E.; Sparrow, P.; Vernon, G. International Human Resource Management, 4th ed.; Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-84398-375-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.L.; Leiter, M.P. The Routledge Companion to Wellbeing at Work; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-317-35372-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L.; Steijn, B.; Nevicka, B.; Heerema, M. The Effects of Leadership and Job Autonomy on Vitality: Survey and Experimental Evidence. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2018, 38, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gosselin, E.; Lemyre, L.; Corneil, W. Presenteeism and Absenteeism: Differentiated Understanding of Related Phenomena. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bunderson, J.S.; Thompson, J.A. The Call of the Wild: Zookeepers, Callings, and the Double-Edged Sword of Deeply Meaningful Work. Adm. Sci. Q. 2009, 54, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, S.N.; Richter Sechrist, K.; Pender, N.J. The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile: Development and Psychometric Characteristics. Nurs. Res. 1987, 36, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.S.; Bruch, H.; Vogel, B. Energy at Work: A Measurement Validation and Linkage to Unit Effectiveness: Productive Energy Measure. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, I.; Taylor, P.; Johnson, S.; Cooper, C.; Cartwright, S.; Robertson, S. Work Environments, Stress, and Productivity: An Examination Using ASSET. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, P.A.; Tytherleigh, M.Y.; Webb, C.; Cooper, C.L. Predictors of Work Performance among Higher Education Employees: An Examination Using the ASSET Model of Stress. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strijk, J.E.; Proper, K.I.; van Mechelen, W.; van der Beek, A.J. Effectiveness of a Worksite Lifestyle Intervention on Vitality, Work Engagement, Productivity, and Sick Leave: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2013, 39, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faragher, E.B.; Cooper, C.L.; Cartwright, S. A Shortened Stress Evaluation Tool (ASSET). Stress Health 2004, 20, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Giga, S.; Cooper, C. Stress, Health and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Employee and Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4907–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 6.0 User’s Guide; SPSS Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work: An Integrative Review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirag, N.; Ocaktan, E.M. Analysis of Health Promoting Lifestyle Behaviors and Associated Factors among Nurses at a University Hospital in Turkey. Saudi Med. J. 2013, 34, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, T.; McCarthy, C. Manage Your Energy, Not Your Time. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Boonyasiriwat, W.; Srisuwannatat, P.; Puttaravuttiporn, V. Are You Working Vigorously? Adaptation and Validation of the Thai Version of Shirom-Melamed Vigor Scale. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2017, 11, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 38.26 | 9.23 | - | ||||||||

| 2 | Gender | 1.54 | 0.50 | −0.20 ** | - | |||||||

| 3 | Physical energy | 3.41 | 0.61 | 0.13 * | −0.07 | (0.89) | ||||||

| 4 | Emotional energy | 3.87 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.16 * | 0.34 ** | (0.80) | |||||

| 5 | Mental energy | 3.49 | 0.50 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.72 ** | 0.40 ** | (0.80) | ||||

| 6 | Spiritual energy | 2.96 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.31 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.31 ** | (0.71) | |||

| 7 | Health | 2.52 | 0.62 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.54 ** | 0.14 * | 0.43 ** | 0.21 ** | - | ||

| 8 | Absenteeism | 7.29 | 1.61 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.22 ** | −0.16 * | −0.31 ** | −0.06 | −0.31 ** | − | |

| 9 | Productivity | 2.05 | 8.93 | −0.00 | 0.07 | 0.47 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.15 * | 0.49 ** | −0.35 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klijn, A.F.J.; Tims, M.; Lysova, E.I.; Khapova, S.N. Construct Dimensionality of Personal Energy at Work and Its Relationship with Health, Absenteeism and Productivity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313132

Klijn AFJ, Tims M, Lysova EI, Khapova SN. Construct Dimensionality of Personal Energy at Work and Its Relationship with Health, Absenteeism and Productivity. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313132

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlijn, Alexandra F. J., Maria Tims, Evgenia I. Lysova, and Svetlana N. Khapova. 2021. "Construct Dimensionality of Personal Energy at Work and Its Relationship with Health, Absenteeism and Productivity" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313132

APA StyleKlijn, A. F. J., Tims, M., Lysova, E. I., & Khapova, S. N. (2021). Construct Dimensionality of Personal Energy at Work and Its Relationship with Health, Absenteeism and Productivity. Sustainability, 13(23), 13132. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313132