Abstract

The process of shaping an entrepreneurial identity is emerging as a focal point in the field of entrepreneurship. Scholarly efforts to date have turned attention to what happens during the process of identity creation, how, and why. In this article, we seek to extend the current literature by examining how entrepreneurs mold their entrepreneurial identities while enacting circular business models. Specifically, identity construction under circular business modeling is proposed as a negotiation process whereby the conflict mechanisms by which entrepreneurs construct their entrepreneurial identities are highly influenced by stakeholders’ interests. Propositions regarding the inherence of stakeholders are presented and discussed.

1. Introduction

One of the most distinctive features of entrepreneurship is that it provides individuals with the freedom to pursue their own goals, dreams, and desires through new firm creation and business configuration [1]. Indeed, prior literature has suggested that entrepreneurs’ decision-making processes on how they configure their ventures often rely on three fundamental questions: Who am I? What do I know? Whom do I know? [2,3,4]. In this sense, entrepreneurial activity is intrinsically an expression of an individual’s identity, knowledge, and networks [2] with entrepreneurial ventures highly dependent on the entrepreneur [5,6]. This conception of entrepreneurial activity is supported by empirical studies which find that entrepreneurial ventures are frequently seen as an extension of the entrepreneurs (e.g., [7,8]).

Despite the above, firm creation is an inherently social activity; therefore, not only does entrepreneurial identity (EI) comprise a self-view through introspective mental representations about what the focal entrepreneur wants to be and what he/she finds important and prefers to happen, but interpersonal appraisals also influence the manner in which the entrepreneur sees him- or herself [1]. In this sense, entrepreneurial activity is intrinsically an expression of an individual’s identity [9]. Consequently, EI is a continuously developed and modified construction process that includes not only the self but also ongoing, mutual give-and-take interactions with others [10,11]. EI is defined as a person’s set of meanings, including attitudes, beliefs, attributes, values, and subjective evaluations of behavior, that define the individual in an entrepreneurial role [12,13].

An extensive body of research on EI has emerged over the last decades [14]. A recent review of this subject reveals that EI spans several market contexts [14] and has a particular influence on certain types of business models. The core argument behind this approach is that the entrepreneur’s desirability, feasibility, and viability are expressed through a business model that is context-depend by nature. While the entrepreneur’s self-identity is the primary pivot from which business models describe, investigate, and design how the entrepreneurial venture will operate, other aspects must also be considered, specifically, EI construction processes under a social constructivism approach.

Extant literature has shed some light on EI in small family firms [15,16], academic categories [17], franchises [18,19], and technology [20,21]. However, studies have not yet covered the influence of circular business modeling (CBM) for the construction and development of EI. Recent studies have identified that sustainable entrepreneurs face an inherent identity tension due to their hybrid business mission [22,23]. Yet, it is often unclear why and how some entrepreneurs choose to elicit business models that do not principally aim at economic performance but rather at closing the energy and material loops [24]. Furthermore, how to manage tension to avoid mission drift is widely unknown. Much remains to be understood, then, in terms of identity negotiation to develop a more holistic and socially grounded explanation of identity construction for sustainable business contexts. This study aimed to fill this gap in the literature, as we see great potential to advance these streams of entrepreneurship research (EI and CBM) to build a deeper understanding of the dynamic social processes of identity construction [25]. We framed our theorizing on the social interactions that enable EI, as well as the stakeholder identities interacting in the context of CBM. This business rationale parsimoniously transmits the notion of social interactions as core elements for businesses to operate and as antecedents behind EI construction processes. In other words, we proposed arguments related to why, how, and when EI under a dynamic system of identities and goals constantly evolves when pursuing CBM.

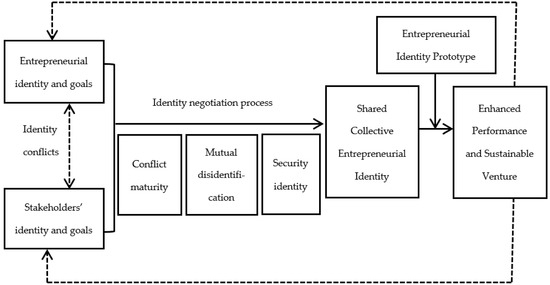

In this paper, we develop a theoretical framework for understanding the intrinsic conflicts and identity-negotiation processes emerging from CBM and its impacts on the identity-construction process. Drawing on the identity conflict literature, we delineate the ways in which conflicts whereby entrepreneurs’ cognitive and affective processes interact with stakeholders’ objectives, desires, and needs mutually transition into a shared collective identity that provides behavioral guidance and self-regulation [26,27]. Further, we establish the theoretical links through which the integration of conflicting identities can lead to enhanced performance while taking into consideration how social identities represent idealized prototypes that define normative standards [28].

Understanding how and why CBM is nested in identity construction is critical as subsequent identity negotiation shapes cognitions, affective being, and behavioral tendencies [29]. Based on the presumption that insofar as people use their self-views to guide their behavior, they may also evoke verifying reactions about identity cues [30], we propose that CBM triggers an intense process of collective identity construction. As entrepreneurs are motivated to have others verify self-conceptions, which is what particularly occurs in CBM, they likely intensify their efforts to elicit confirmatory reactions when they suspect they are being misconstrued [31]. Hence, entrepreneurs enacting CBM are genuinely more inclined than other entrepreneurs to elicit confirmatory feedback from stakeholders [32].

First, we examine why CBM is particularly relevant for EI. Second, we briefly review major findings concerning the interface between affect and cognition in EI construction. In the third section, we then use the information presented in these initial discussions to develop a theoretical framework concerning the impact of CBM on several key aspects of EI (e.g., the process and dynamics). In the final section, we examine the implications and potential contributions of the present framework.

2. Why CBM Is Relevant in the Design of EI

Some of the most promising theories for studying EI are through the lens of social identity theory. This theory suggests that identity serves as a cognitive frame and is therefore helpful to understand how symbolic interactions with others emerge by conferring interpersonal insights that guide the identity negotiation process. In this regard, prior studies have explicitly linked the conception of EI, as a reflexive journey characterized by negotiations with others, with the conceptualization of the entrepreneurial venture, as a networked social process [33]. Accordingly, considering that entrepreneurial activities can be conceived as an expression of an entrepreneur’s identity [1], it is also plausible that the business model that an entrepreneur selects is infused with meaning since the entrepreneur has chosen it as a means to reach his or her goals [34]. A business model describes the design or architecture of mechanisms for creating, delivering, and capturing value [31,35]. It covers decisions about how a company implements a strategy to organize its operations to generate profit from meeting the needs of its customers [36]. Therefore, the business model is essentially a conceptual logic, and its rationale is directly linked with the founder, up to the point that is frequently considered an extension of the entrepreneur. EI is tinted with the meaning of the business model that entrepreneurs select; thus studying EI without considering the context (i.e., how entrepreneurs decide to exploit the business idea) only confers a partial understanding of the phenomenon.

While some entrepreneurs have an innate awareness of the relevance of sustainable business, there is also a whole stream of evidence about the increased relative importance that the natural environment has gained in business [37], which has fostered the emergence of several business models for sustainability [38]. The core logic of these business models is to embrace a broader and more holistic perspective of value that not only includes economic, social, and environmental factors but also stakeholders [39]—in other words, business models that make it possible for businesses to reconcile profit with the planet and people. This type of business innovatively interplays the firm’s business model, embracing it into an alliance-networking level [40]. One type of business model for sustainability is CBM [41]. CBM is defined as the rationale that a focal company together with partners uses to create, capture, and deliver value to improve resource efficiency by extending the lifespan of products and parts, thereby realizing environmental, social, and economic benefits [42]. Therefore, CBM differs from traditional business models in its objectives, as it does not principally aim at economic performance [24]. Instead, it creates, delivers, and captures value with and within closed material loops [43,44,45]. Entrepreneurs adopting CBM tend to develop recycling measures (cycling), use phase extensions (extending), implement a more intense use phase (intensifying), and substitute products with services and software solutions (dematerializing) [46,47] to reduce the resource inputs into and the waste and emissions from organizational systems [46]. Evidently, such practices cannot be implemented in isolation but require stakeholders’ engagement [48]. Consequently, CBM emphasizes the need to engage all relevant stakeholders, which in turn requires changing the classic “customer-oriented” business perspective into a “multiple stakeholder” perspective [49,50]. For example, implementing CBM necessitates waste- and resource-reduction practices that require the engagement of stakeholders beyond the traditional perspective, including all relevant stakeholders and not just customers (users/consumers) [50]. Implementing CBM is challenging due to the complexity, risks, and uncertainties that come with collaboration [51].

CBM is by nature networked as it requires collaboration, communication, and coordination within complex networks of independent yet interdependent stakeholders [49,52,53]. In this sense, entrepreneurs need to explicitly focus on their relationships with their key stakeholders [54] because interactions with these stakeholders are critical for the success of new ventures [42] and any weak link in a venture’s whole ecosystem could cause business failure [49]. Indeed, without collaboration, achieving circularity is hardly possible [55,56]. Moreover, creating positive relationships with stakeholders is an important condition for performance optimization in the long term [50]. Thus, entrepreneurs are highly dependent on their stakeholders for establishing a system where resources are reused and kept in a loop of production and consumption [44,57].

The literature has identified numerous stakeholders, including ventures’ workforce, shareholders [58], supplier partners [59], policymakers, business associations [60], nongovernment organizations [52], community partners [61,62], universities and research centers [50], and investors [50]. As such, securing the engagement of stakeholders is a transactional process that requires aligning the preferences of various stakeholder groups [58], as well as integrating and coordinating requires an understanding of their current needs and operations along with a holistic consideration of their role in the entire circular ecosystem [49]. In this complex system, entrepreneurs have to establish effective communication with their stakeholders to set common goals between all actors in the value chain [57]. In order to do so, stakeholders’ expectations are particularly relevant as essential conditions to consider for a company’s growth in the long term [50] since the implementation of economic activities according to circular economy principles [63] can only be fulfilled by maintaining relationships with stakeholders. (We acknowledge that the conceptual logic of CBM is aligned with the sustainable development values derived from the review of the Brundtland report: (1) simultaneous progress to maintain and/or grow economy and raise living standards within environmental limits; (2) intra- and inter-generational equity; (3) whole-system perspective; (4) change in social values to balance economy with the environment; (5) sustainable resource use; (6) natural capital does not decline over generations; (7) collaborative change; and (8) implementation is context-dependent [63].) Hence, it is expected that collaboration between actors in an ecosystem will generate mutual understanding [62,64], constant feedback, and mutual efforts [49,65].

Even when CBM is not customer oriented, it is important to remember that customers are still the most important stakeholders because the survival of any company depends on their acceptance [42]. However, fulfilling customers’ expectations is often difficult because they do not just want products—they want solutions for their perceived needs. Indeed, prior literature has evidenced that one of the main reasons for entrepreneurial failure is not emphasizing customer feedback [66].

Thus far, we have established that the relationships between entrepreneurs and their stakeholders are a key factor for successful circularity (by successful circularity we mean being part of a system that together closes a material loop [43]), but CBM still has many challenges to overcome mainly due to the intricate and necessary interactions among the various players, with their respective perceptions of value arising from potentially conflicting objectives [36]. Tensions could arise in these interactions because stakeholders’ interests and driving forces do not always align [42]. Therefore, it is important to be aware of the potential problems with CBM, such as misalignment of incentives, incompatibility with partners’ business models, lack of supply-network support, conflicts of interest within companies, and misaligned profit sharing along the supply chain [45,53]. Further, entrepreneurs adopting CBM need to understand and create incentives for key partners since they have to anticipate potential claims from stakeholders about moral and ethical grounds while also actively generating value [49].

Accordingly, the proposed theoretical framework is developed around the premise that CBM has a primary influence on entrepreneurs’ identities. The core argument is based on prior studies about identity revealing that people, including entrepreneurs, incorporate the perspectives, resources, and characteristics of close others into their own self-concepts [67]. Hence, entrepreneurs’ stored representations of the self and stakeholders play important roles in shaping the self by guiding the cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioral patterns that become activated in particular contexts. For the purpose of this framework, the particular context is embedded under a circular logic. Therefore, the EI-construction process emerges from interpersonal patterns that reflect the various selves an individual has developed in the context of relationships with stakeholders [68].

Our approach resembles recent studies positing that circular entrepreneurs’ identities are broken down and formulated in the entrepreneurial vision and stakeholder interaction [69]. We develop the idea that CBM induces entrepreneurs to accept a relatively complex stakeholder structure due to its systemic character. We thus frame our argument around conflicting identities that evolve into a shared collective identity as a result of an identity negotiation process from which enhanced performance outcomes, such as social, ecological, and economic benefits can be achieved.

3. The Influence of Negotiating EI: Underlying Mechanisms

To establish the link between EI under CBM, we draw on the identity conflict literature [31,70,71,72]. In this context, EI is a potentiality that can change rather than a fixed personality trait with a causal influence on individuals’ entrepreneurial behavior [73]. According to this approach, individuals often have multiple identities that may conflict with each other. For example, how people perceive themselves is conceptualized as the “actual self”, while how people would like to be is conceived as the “ideal self”, and the two can be in conflict [74,75]. Identity conflict occurs when the behavioral expectations of one identity conflict with the behavioral expectations of another identity [76]. For example, “I do not like who I am, so I am not proud of my identity as the reflection of my current behavior.” In these kinds of situations, individuals experiencing identity conflict can alter their attention, beliefs, and behavior to trigger the identity-change process, or they can alter also the expectations of others to overcome identity conflict [77].

The crucial point here is that identity is not developed in a vacuum; rather, symbolic interactions with others also provide a system of categorization for and influence the establishment of an identity [78]. According to this theoretical approach, social norms provide frameworks for identifying the most appropriate actions in any situation [79] and thus confer some interpersonal principles that guide identity negotiation. In other words, social norms and interpersonal patterns provide the basis for the various social identities an individual has constructed in the context of relationships with significant others. Among these identities are the social self (how people feel others see them), expected self (how people expect to see themselves at some future time), and ideal social self (how people would like others to see them). Within this construction process, not only does identity conflict comprise a self-view through introspective mental representations, but interpersonal appraisals also influence the manner in which individuals see themselves. For our purposes, the structure and function of identity are constructed in an individual’s social relationships and his or her membership in groups or social categories. Therefore, we categorize the self into several micro-identities, which are manifestations of a person’s identity under different perspectives based on the notion that social identities confer normative standards for thought and action, thereby profoundly influencing the behavioral choices of individual group members [79].

Previous literature has identified that identity conflicts can be divided into cognitive (Type C) and affective (Type A) conflicts. Type C conflicts occur when team members have different opinions on specific issues, whereas Type A conflicts result from emotional distress in interpersonal relationships [80]. Briefly, Type C conflicts can manifest through disagreement and productive debates about innovative tasks that often arise from differences in perceptions, practices, and representations based on different points of view and expertise [81], and Type A conflicts can emerge from relational disputes, such as disidentification that is expressed in strong emotions such as hatred, pride, and fear [82,83,84,85]. The importance of the interface of these identity conflicts in entrepreneurship has been illustrated by several studies. For instance, substantial research has shown that cognitive and affective conflicts indirectly influence performance through conflict processes [86]. Thus, interpersonal conflict management is important for entrepreneurial teams in terms of boosting creativity, facilitating collaborative learning, and clarifying personal identities [87,88]. In addition, the ability to resolve interpersonal conflicts is among the key factors determining whether an individual is prepared to become a competent entrepreneur [89].

In this regard, environmental knowledge plays a fundamental role. In the knowledge economy, where sustainable development is becoming the mantra for the future [8], environmental knowledge helps determine how to manage the organization–environment duality [9,10]. Environmental knowledge is a general understanding of facts, concepts, and relationships relating to the natural environment and its major ecosystems [11]. It can also be described as a system that connects data, analytics, and people and presents an opportunity to formalize the ecology in an enterprise environment [12]. Thus, environmental knowledge implies what is common knowledge for society about the environment [5], the key relationships leading to the environmental aspects or impacts, and an appreciation of the systems and collective responsibilities necessary for sustainable development [13,14]. In the context of CBM, there may be differences in the interpretation of environmental knowledge. These interpretative differences between the entrepreneur and the stakeholders may create conflict regarding how to bring that knowledge into the business. If so, this would result in a scenario of identity conflict. Thus, we suggest that the starting point for understanding EI construction in a CBM context relies on cognitive and organizational adaptability. Cognitive adaptability is the ability to effectively and appropriately adapt decision policies based on feedback from the environment in which cognitive processing is embedded [90]. Analogically, organizational adaptability can be understood as the ability of organizations to remain cognitively flexible to respond to changes in today’s volatile socio-economic context. Considering that business strategies are often influenced by the growing global concern for the environment and its protection, adaptability seems to be particularly important [5]. Thus, more and more organizations are incorporating environmental and sustainability challenges into their strategies and daily operations [6,7].

Given the breadth of the effects described above, it seems clear that identity conflict automatically requires initiating a process of identity negotiation [68], which occurs when agreements regarding the identities assumed in interactions are reached [91]. After all, several of these effects appear to be directly related to activities that entrepreneurs perform when starting and managing new ventures [92]. Thus, these mechanisms provide a useful basis for understanding identity negotiation as a dynamic process throughout any entrepreneurial effort [72]. In this paper, we introduce, elaborate, and illustrate the logic that supports this theorizing. To ground this logic in practice, we draw upon the experience of Chilean entrepreneur Pamela Castro and her circular entrepreneurial venture (Modulab), which has been pioneering upcycling and eco-design. We explore how her initial EI evolves as she manages her venture according to a CBM structure. The business idea originated after Pamela watched a film and realized the enormous amounts of PVC paper that end up in the trash once films are pulled from the cinema billboard.

Modulab is an entrepreneurial venture dedicated to managing other companies’ waste with which it creates innovative products. The mission of the business is to raise social awareness about the environment. For instance, they work with the National Board of Firefighters of Chile (initiative called ON FIRE) where Modulab creates a wide range of products, including backpacks and kitchen gloves, built using the firefighters’ waste (from uniforms to fire trucks).

In the remainder of this paper, we develop specific propositions concerning the potential role of CBM in key aspects of the EI-construction process.

4. The Construction of an EI in the CBM Context

Prior literature has shown that entrepreneurs are often identified by their ventures to the point that their ventures are frequently considered an extension of them [93,94]. In this context, initial identity includes a range of behaviors, attributes, and thoughts that ensure an individual’s coherence and distinctiveness [95,96] and also define his or her motivations, self-evaluations, and frames of reference [1,97]. In consequence, EI is precisely aligned with how an entrepreneur determines the type of venture he or she will start and its functioning [14]. This is evidenced by the example of Pamela Castro, who always dreamed of changing the world and contributing to social and environmental solutions but always from a design perspective. She defines herself as an environmental social entrepreneur. Modulab was conceived as a social activism project to counteract the environmental damage generated by different industries (e.g., entertainment, fashion/clothing, among others) that are characterized by programmed obsolescence and fast fashion. Another venture of hers, called ReparaLab, undertakes free collaborative repair workshops, where people are taught how to repair used or worn products (e.g., appliances, footwear, and clothing). ReparaLab gained strength as a response to the global pandemic by centering mostly on the construction of sustainable masks. By doing so, Pamela contributes to offering jobs to unemployed individuals and delivering local economic impact, as they only hire people from the area where the customers live.

Under this frame, the social construction of identity induces the emergence of “relationship goals”, which are the desired end states people strive for when they enter social interactions [98]. Considering that any social interaction involves at least two parties, identity conflicts emerge naturally from discrepancies in parties’ predefined goals and initial identities, which generate tension [79]. Identity conflict is defined as a situation or circumstance in which there is incompatibility between two or more individuals’ identities and appraisals [98,99]. While the CBM logic structure and its requirements for adequate implementation provide the guidance from which entrepreneurs’ identities and their relationship goals are constructed [1,14], each stakeholder has his or her own preset goals, which may or may not be aligned with circular logic. Indeed, empirical studies have uncovered different tensions, including in relation to generating economic value or protecting social/ecological value or in regard to the frame of reference [22].

Discrepancies between stakeholders and entrepreneurs about their initial identities and goals play integral roles in determining the intensity of identity conflicts [68,76] since identity conflicts materialize from the joint contributions of both parties. Indeed, recent studies have suggested that stakeholder enrolments require a social process characterized by commonality, mutuality, and reciprocity [25]. Upon engaging in a social interaction, people—consciously or not—verify their self-perceived identities, and such verifications can be displayed at different levels (e.g., personal self-views, collective self-views, and group identities) [100,101]. Considering that CBM demands stakeholders’ active participation, a network logic is imperative for accomplishment [49,53]. This notion of conflicting identities that emerges intrinsically from CBM can be seen in the process of enrolling stakeholders. Pamela constantly encourages companies to raise awareness of the relevance of caring for the environment and inspires other firms to act accordingly. She attempts to push companies to begin to incorporate the environment, and the social system,

“…but not as an area only -an area of sustainability or community area- but that companies feel that they have to be a contribution to society and generate not only economic, but social and environmental value, and that they do it for real”.

Hence, the underlying logic of CBM forces incumbents to verify their self-conceptions and social identities. In turn, this reasoning indicates that entrepreneurs who adopt CBM are more likely to be exposed to identity conflicts. Thus, we propose the following:

Proposition 1.

CBM intensifies vulnerability toward identity conflicts between entrepreneurs and stakeholders.

As we previously stated, CBM can be conceived as a representation of identity as it provides guidelines about how to organize one’s assets, resources, and behavior. As such, it is critical that this structure of business modeling remains relatively stable [102] to frame the social interactions between entrepreneurs and their stakeholders. In this sense, although stakeholders may not necessarily share entrepreneurs’ affinity for sustainability, entrepreneurs who adopt CBM have EIs embedded in an ecosystem perspective of doing business [1]. Considering that a business ecosystem refers to a value-oriented network composed of numerous stakeholders [103,104,105,106], this perspective describes the process of organizations that collaboratively create some kind of system-level values [107,108]. Accordingly, we pose that it is within this business ecosystem that EI evolves, as it recognizes a shared purpose as a community [109,110]. In consequence, during social interactions, entrepreneurs must use as many channels of communication as possible to convey their desired identities to stakeholders [111].

Because behavior is perhaps one of the most effective ways for individuals to communicate how they make sense of the world, it is important to note that entrepreneurs may communicate their identities before they even open their mouths by displaying identity cues [31,112]. For example, just the act of collecting supplies through customers by itself projects a particular perceived identity of the entrepreneur to them [1]. Accordingly, the way entrepreneurs arrange and design their ventures’ names, websites, offices, merchandising, etc., elicits identity cues. Therefore, two key issues are imperative for social identity construction. First, EI requires showing behavioral coherence to somehow guarantee consistent evaluations from others. Second, when others have difficulty seeing one’s EI congruently, using multiple communication channels to communicate this EI is especially helpful to achieve clarity [31]. We see this in Modulab’s partner-seeking process since Paula deliberately endeavors to collaborate with firms that have a clear organizational purpose and statements about their identity, such as Patagonia (a Californian clothing company). By focusing efforts on companies that have coherently alike identities, Paula increases the likelihood of finding sense-making activities that align with her purpose and identity. This, as social identity is grounded in specific aspects, such as organizational culture, and an enrollment process would be easier with organizations that transmit coherence and clarity in their social identity.

Considering that one of the main identity-related goals of entrepreneurs is to ensure the feasibility of CBM [1,102], they need to shape the minds of stakeholders through a process of identity negotiation. Thus, there is a need to move beyond a sense of trade-offs between stakeholders to satisfy multiple and conflicting objectives to explore win/win and synergistic opportunities [51]. As such, and to overcome identity conflicts in this process, entrepreneurs must deploy a host of interpersonal identity-negotiation strategies [98,99]. This negotiation process involves a broad spectrum of aspects through which people strike a balance between achieving their interaction goals and satisfying their identity-related goals but encourage commitment and buy-in from external parties [4]. Studies have characterized this negotiation process as comprising three stages: the first involves certain adjustments between identities, the second entails identity verification between parties, and the third includes interpersonal agreements [113,114].

Consequently, during the first stage, entrepreneurs need to work on identity adjustments to provide clear cues about boundaries and reduce tensions that exist during deliberations. Second, upon communicating their identities, entrepreneurs must wait for their stakeholders’ “counteroffers” and then respond accordingly. If entrepreneurs suspect that they are being misconstrued, they need to intensify their efforts to elicit self-confirmatory reactions. However, it is important to acknowledge that identity signals may not always be successful in shaping stakeholders’ perceptions. Finally, both parties need to compromise by following each concession on the other’s part with a concession of their own—like a loop in terms of identities [100]. That is, entrepreneurs should acquiesce to stakeholders’ wishes and offer consistent behaviors that validate their preferred identity. Indeed, a tenet for identity-negotiation theory is that as their relationship unfolds across time, both parties in a relationship should remain faithful to their negotiated identities [115]. Further, people need to strive to maintain compatibility among the various identities that they negotiate. This occurred to Paula as she shifted the product development process of Sodimac to an alternative model. Sodimac has a traditional “do it yourself” campaign which is a reflection of their organizational culture. Paula considered that a tutorial about basic construction or assembly (that emerges from Sodimac’s organizational values) and reuse (that emerges from Modulab)—which was the initial agreement for content—had a marginal value-added and an insufficient potential impact. Since Paula considers repair and recycling to be revolutionary acts, she moved forward with the idea of producing an instructional video about how to design a bench using a disused bed.

Taken together, we propose that identity grows out of the interplay between self (entrepreneur), situation (CBM lineaments), and others (stakeholders) [31]. That is, the mutual give and take that occurs between entrepreneurs and stakeholders assumes that the process of identity negotiation is a fundamentally interactional phenomenon [114]. While entrepreneurs seek to socially legitimate their behavior according to normative structures [13,79], they test the social acceptance or approval of their identities [116,117,118,119]. As a result, during this identity-negotiation process, EI boundaries seem to be shaped by stakeholders’ expectations [113]. Based on this reasoning, we propose the following:

Proposition 2.

Identity negotiation among entrepreneurs enacting CBM is permeated by stakeholders’ identities.

As with every negotiation process, it is required that both entrepreneurs and stakeholders go through identity shifts for conflict resolution [120]. In other words, for an identity negotiation process triggered by conflicting identities to end successfully, both parties must be motivated to resolve the conflict [121,122,123,124]. This predisposition to resolve differences is what the literature recognizes as mature conflict [125]. Maturity implies a willingness to change the nature of relationships from a competitive, desperate, and destructive orientation to a more cooperative coexistence with potential for mutual benefit [126]. An important aspect to consider is that the benefits elicited by the cooperation—acting as a form of motivation—must be such that they succeed in twisting distorted information processing for those involved to commit to change [120]. If so, conflict maturity is achieved once those involved perceive benefits from changing the way in which they conduct their relationships [120,125,126,127,128,129]. Thus, maturity may prevent conflicts from escalating to levels of intransigence that can cause serious negative consequences at the individual and organizational level [130]. For instance, prior literature showed that the lack of maturity can alter organizational members’ behavioral attributions, distort communication relationships [123,131,132], reduce learning, and increase turnover [133]. In such scenarios, organizations have few options to achieve benefits, such as flexibility and creativity [134], leading to strained working and support relationships and thus threatening the survival of organizations.

The disposition generated by conflict maturity helps individuals to become more willing to consciously dissociate their identities and eliminate negative sources of identity [120]. By doing so, a willingness is intrinsically assumed to enter into a state where there is a feeling of vulnerability that leads to losing confidence in one’s own identity [120,135]. As a result, individuals go through a process of disidentification, from which they define who they are by establishing who they are not [85,136,137]. In other words, during this disidentification process, individuals create psychological distance with what creates dissatisfaction by adopting attitudes, possessions, and behaviors to convey both who they are and who they are not. By doing so, individuals establish an identity that distinguishes them from those they view negatively. Accordingly, mutual disidentification is a state of simultaneous disidentification that is reinforced by the cognitive simplifications of one counterpart, who ignores the potential of others’ identities [82,120,128,138,139,140]. In our case, mutual disidentification is conducted by both entrepreneurs and stakeholders during this identity negotiation process.

The process of disidentification is sensitive, delicate, and complex since indirectly implies that individuals must embrace uncertainties about their identities. As such, disidentification has a strong evaluative/affective component expressed in strong emotions, such as hatred, pride, and fear [82,83,85,140,141]. A potential reason behind this relies on the fact that during the process of disidentification, individuals may unintentionally expose pivotal beliefs from which inner inconsistencies potentially emerge. Consequently, it is reasonable to find prior evidence suggesting that disidentification is one of the main reasons why conflict is so difficult to resolve [121,122,123].

The process of mutual disidentification could negatively affect the conflict if individual identities are threatened [142,143]. In these circumstances, the identities of the conflicting parties are negatively interdependent, and thus a key component of each group’s identity can be based on denying the counterpart [122,139,140]. If so, the presence of a superior common goal may lead conflicting parties to accept each other and achieve harmony. For instance, identity-related goals can act as motivators centered on avoiding that one identity is invalidated by another group [128,132,144]. This in turn may encourage a construction process of a supra-identity generated by peer influence [145,146]. This new supra-identity can be conceived as the juxtaposition of individual identities acting collectively.

Despite the above and regardless of the specific terms of the negotiated process, identity conflicts are always latent. Therefore, boundary conditions of the mutual agreement are particularly relevant as they have to be as broad as possible to achieve greater counterpart acceptance [120]. The mutual commitment with the identity negotiation process will remain strong to the extent that positive emotions allow verification and approval of the counterpart identity so related goals differences do not turn into negative emotions [82,140,141,147,148,149,150]. For example, discordant behavior can threaten the identity negotiation to the extent that those involved do not recognize the validity of the other’s worldview [122]. Evidence suggests that this invalidation can cause a distortion of information to conform to prior beliefs [123,131,132].

Once the parties involved go through the process of mutual disidentification, they no longer need to look for sources of positive distinction because they have developed a sense of identity security. The security of an individual identity is associated with the acceptance of the supra-identity because individuals reach a psychological state that allows them to accept superior identities more easily [120]. For this to occur, the mutually disidentified identities must be decoupled from each other so that the identity security of one does not depend on the disappearance of the other [31,70,71,72]. Decoupling, in this context, implies a psychological state of separation, dividing the elements of identity that bind the two parties in the destructive dance of mutual disidentification. The security of an individual identity is a representation of a strong commitment obtained by way of a strong dual identity to achieve harmonious relationships [76,151,152].

On the one hand, Pamela sought to establish an alliance with the Chilean Fire Brigade. However, the fire brigade, as a non-profit institution, had never signed a commercial agreement with private companies, and thus they were reluctant to enter into an alliance. Further, firefighters’ own self-identification, who see themselves as volunteers and selfless, was also a barrier to cooperation. Over the course of the discussions, both parties recognized the potential benefits of a partnership and endeavored to reach an agreement. The aim of the alliance was to use the waste produced by the firefighters as an input to develop marketable products, taking advantage of the experiential value of each material and firefighters’ position and reputation in society. The fact that the alliance has come to fruition reflects the predisposition of both parties—that is, the maturity of the conflict—to negotiate their identities in search of cooperation.

The process of identity negotiation progressed toward a stage of mutual disidentification. On the one hand, the Chilean fire department was reluctant to allow a for-profit company to market their image, as it may impact societal perception. On the other hand, in normal circumstances, Pamela—who did not identify herself as a traditional entrepreneur—was not predisposed to give up control over the sale of her products to third parties because the message of sustainability that she intended to deliver through her products could be lost.

Despite the above, both parties reached an agreement after adjusting their initial positions. The firefighters provided Pamela with the materials and equipment that were useless to them, understanding that Pamela shared a similar objective of caring for the environment. Pamela, in turn, transformed the waste into products but did not sell them directly. Instead, she gave them to the fire department so that they could be displayed in their stations for sale to the public.

Given that the identities were both linked to the environment and to the aim of fulfilling a positive social contribution, the two parties identified a solution. The security of the firefighters’ identities is linked with preserving the core values of the institution. Similarly, Pamela can safeguard her purpose of shifting the current consumer culture toward a culture of sustainability.

“… The key was to integrate, as both parties found a nexus through a material that had a history and an identity underpinned on creating value. The domestic products that MODULAB creates from firefighters’ clothing are more than just objects. What consumers wear is permeated with value and meaning, as it is manufactured using a material that is instrumental for firefighters to do their jobs; protect their lives and solve 500–600 emergencies. This identity transcends the fire brigade as an institution, as it is the identity of firefighters as volunteers of Chile”.

To sum up, successful identity conflict development requires a level of maturity such that negative differences can be resolved in a process of mutual disidentification whereby the security of individual identities generates the conditions to maintain harmonious relationships. This in turn implies that identity-relationship goals are aligned through a conjoint desire of constructing a supra-identity collectively. This rationale leads us to the following set of propositions:

Proposition 3a.

Conflict maturity increases the probability of mutual disidentification.

Proposition 3b.

Mutual disidentification promotes security in individual identities.

Proposition 3c.

Security in individual identities strengthens the supra-identity as a result of a successful identity-negotiation process.

Agreements about mutual engagement and a common intentionality to avoid identity conflicts are not sufficient to lead aligned managerial efforts. The feasibility of CBM depends on eliciting positive evaluations from stakeholders about the focal environmental dimensions and contributing accordingly. Indeed, developing an identity based on the scope of CBM requires logical consistence and thus necessarily puts high relative importance on negotiation in order to establish clear boundaries, distinctive management criteria, self-awareness, and unambiguity toward the environment [31,153]. These factors foster identity stability by conferring purposeful actions to maintain core aspects of both identities that were negotiated. This supra-identity construction process will flow smoothly to the extent that entrepreneurs’ and stakeholders’ identities match because they will be better able to predict reactions and behaviors within the CBM context and their role in this relationship [154].

While evidently there are no absolute guarantees in entrepreneurship, evidence suggests that the process of identity negotiation can be fruitful [155]. On the one hand, during social interactions, interpersonal feedback is often ambiguous and thus prone to interpretation [73]. As such, entrepreneurs and stakeholders have to prioritize relationships that match the principles of CBM [63] and forgo some features of their initial identities if needed [68,76]. It is important to note that in parallel to the identity-negotiation process described above, a whole set of cognitive resources (e.g., attention, interpretation, and reasoning) and affective processes (e.g., moods, emotions, and feelings) are functioning [31], and since identity is central to how people make sense of the world, compromising with initial identities tends to intensify conflict [123,130,132] to the point of entering a conflict spiral from which it is difficult to escape [82,128,156]. In this regard, entrepreneurs are particularly susceptible to relying on heuristics and other cognitive biases that facilitate the maintenance of coherent and stable identities even when they engage in interactions with stakeholders who view them in identity-inconsistent ways [157,158]. On the other hand, entrepreneurs are often successful in developing strategies designed to shape stakeholders’ identities and goals [1]. Concretely, entrepreneurs tend to use narratives to enact greater sense making in stakeholders, which frequently increase the odds that their identity claims will be accepted [14,159]. Hence, in terms of entrepreneurs’ relationship goals, the focus has to be on prioritizing a fit to solve the identities conflict rather than the maintenance of their initial identities, where maintaining behavioral stability contributes to some sort of harmony with other identities unfolding smoothly [100,158].

Entrepreneurs need to work on organizing efforts between all involved stakeholders of their CBM in order to establish agreement among them [160,161]. Some studies have defined this process as a working consensus [113,162]. This consensus is broader than joint desirability shared by all involved stakeholders, since it covers fundamental issues, such as entrepreneurs’ and stakeholders’ guidelines about how to move forward and remain jointly engaged in their organizing efforts [41]. Thus, the frame of reference from which this new supra-identity rests is essentially the construction of a CBM structure. Accordingly, the result of the identity-negotiation process can be conceived as a shared collective identity [113]. This shared collective identity reflects not only behavioral, cognitive, and affective components but also the constraints imposed by CBM [163]. This collective identity is conceptually different than an entrepreneur’s initial identity, but the two overlap [120]. Indeed, the collective identity can be conceptualized as a macro-identity within a specific circumscribed situation [164]. This collective identity is the legitimization of certain values resulting from the interpersonal negotiation process [116,117,118,119].

Forming a working consensus relationship around CBM principles sets the territory to pursue the goals that brought the entrepreneur and stakeholders together in the first place [165]. The extent to which the consensus works for both parties will influence a wide array of outcomes [154]. For example, as a consequence of constructing a collective identity, collective cognitions emerge [166,167], such as mutually agreed-upon expectations and team cohesion, thereby transforming disconnected individuals into collaborators who have obligations, goals, and commitments [168]. According to Pamela Castro, this is accomplished by attaining a shared purpose and sticking to it. In the case of firefighters, beyond the product itself, a story is bought with emotion behind it and at the same time collaboration to market dynamism, industry competition, and product diversity. As negotiated factors remain, they will support stability in this identity since they will remind the conjoint purpose and a new set of objectives aligned with the CBM structure concealing meaning by emphasizing certain interpretations and restricting others toward a working consensus. Therefore, we propose the following:

Proposition 4.

When CBM is pursued, the construction of a stable EI is reached through a shared collective identity.

Once an entrepreneur and his or her stakeholders have established the boundaries of a collective identity, new goals can be set [113,169]. In this collective identity, a working consensus among entrepreneurs and stakeholders is fundamental since it catalyzes positive energy and enthusiasm [139], which in turn positively impacts performance [1]. Several studies have suggested that internal congruence within this collective identity (i.e., the integration of an entrepreneur’s and his or her stakeholders’ identities) may lead to several favorable managerial outcomes [168,170], such as increased commitment, team integration, and better economic performance [166,171,172].

The regular exchange of thoughts, ideas, and critiques may promote the adoption of a holistic perspective of doing business and simultaneously encourage socio-ecological innovative capabilities. From this, new forms of intra- and inter-organizational relationships may become embedded in a corporate identity, emanating from a mission to pro-actively influence society [173]. Thus, by taking actions to reduce negative impacts on the environment, organizations can directly and/or indirectly improve their business performance [174,175,176].

Here, it is important to note that financial results are not the only benchmark for entrepreneurial performance. A comprehensive understanding of identity requires attention to social and spatial processes, not just economic processes [177,178]. As we previously mentioned, CBM necessitates moving beyond environmental regulations [179,180] in pursuit of broader outcomes, including social performance [62,181,182,183]. Social performance is defined as a business organization’s configuration of social responsibility principles, social responsiveness processes, policies, programs, and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s societal relationships [184,185]. Prior studies have evidenced that social performance increases the engagement of both entrepreneurs and stakeholders in businesses [84,186]. In consequence, under a CBM context, business performance involves both social and economic dimensions. Modulab’s alliance with travel agency Rai Trai exemplifies this. Under this agreement, school students send their old jeans to Modulab throughout the year. Students get to participate in the process of selling derivative products while also financing (in their totality) their year-end study tour.

Along with the enhancement in team commitment, there are also antecedents suggesting that individual benefits can also be accomplished with the development of a collective identity. For instance, one of the most intrinsic needs of people is a sense of being a member of an in-group, which is often referred to as inclusiveness [187]. Fulfilling the need for belonging is a powerful pervasive motivation that improves feelings of self-worth [76,151,152] and generates positive emotions [188,189]. These in turn are positively related to enhanced cognitions, such as perceptions, creativity, heuristic processing, memory, and interpretation of others’ motives [190,191,192,193,194]. Therefore, clarity about identity cues and behavioral coherence between incumbents should flow more parsimoniously. This can be seen in Modulab and their alliance with firefighters where Pamela mainly develops products for children (such as pencil cases). Firefighters are perceived as “heroes” by children. Thus, since children love firefighters, it is intended to instill a sense of belonging and identification with the institution. Thus, firefighters win, Modulab wins, and children (as users) win.

Further, prior evidence has noted that when people are seen as they see themselves—when they realize similarities between the ideal self (what people would like to become) and the actual self (how people perceive themselves)—they exhibit heightened psychological and physical well-being and are more productive and satisfied in the workplace [100]. Analogically, there is evidence suggesting that when there is disconformity with this collective identity, individuals are prone to leaving [195,196], breaking the circular structure of the business model [120]. Therefore, the likelihood of reaching sustainability around the CBM system is enhanced.

To the extent that the new shared collective identity and new set of goals are consistent among the focal entrepreneur and his or her stakeholders [68], they should be well positioned to achieve the outcomes they desire [197,198,199,200]. A consensus between expectations and social performance avoids the negative edges of identity conflict and promotes a sense of unity between entrepreneurs and their stakeholders [201]. Thus, the collective identity generated under CBM may act as the unity framework that drives positive outcomes (i.e., social and financial performance, clarity and coherence in identities, and a sustainable business model). This working consensus, in turn, will lead to environmentally friendly and economically sustainable businesses. Before working with Modulab, firefighters had to pay for their waste to be collected. Now, Modulab provides them with a monetary donation, based on a percentage obtained from their sales (economic profitability). This also generates social profitability, since Modulab contributes to strengthening the links between the community and the firefighters. According to comments in an interview made by Matias Soublett (captain of the fourth fire brigade of Ñuñoa), the institution has 99% effectiveness and satisfaction toward citizens, and “That makes super important that the identity of Chilean firefighters is not lost”. Furthermore, firefighters obtain environmental certifications. This reasoning leads to our next proposition:

Proposition 5.

A shared collective identity enhances CBM performance.

Prior studies argued that entrepreneurs are able to construct different and unique identities by how they position their firms relative to other firms [99], with these individual differences manifesting through elements of personality, hierarchies of values, attitudes, expectations, cognitions, meanings, and motivations [202,203,204,205]. As we argued above, an entrepreneur who adopts CBM is expected to behave following CBM principles and the way he or she interprets those principles, and the entrepreneur’s identity evolves with his or her stakeholders’ identities, creating a new conceptualization of a shared identity as a result of negotiation. As such, stakeholders are also prone to triggering adaptations of their identities and goals in an attempt to pursue CBM. In a nutshell, CBM principles shape the identities, goals, and strategies of everyone involved, transforming them into a socially defined collective self [206,207].

By definition, the identity embodied in the CBM logic is not developed in isolation [48]. Instead, an individual’s self-concept is attached to a process of identity construction following a perceived prototype about socially identified core characteristics [113]. Prototypes bring people’s cognitive representations of their collective identities and offer a common standard through cognitive representations that describe behavioral norms, hierarchies of values, beliefs, feelings, and attitudes that form the basis for making meaningful distinctions between members of different groups [208]. In consequence, a collective-identity prototype provides guidance about why efforts are organized with value and meaning to accomplish the new set of consensual goals [124]. In this sense, a prototype is an abstraction of the underlying reasons for action. We suggest that the extent to which entrepreneurs’ and stakeholders’ interpretations of a CBM structure are alike in terms of downplaying or emphasizing aspects of perceived collective cognitions and team cohesion may play a key role in overall system performance [209].

CBM induces a complex system in which members construct their own roles and extends this interpretation to interactions with other members in shaping both the collective identity and goals. Here, complexity arises from the constant interactions between the multiple individual identities involved in the CBM system. In this sense, any accretion of mismatched perceptions, beliefs, and behavioral norms reflects ambiguity in patterns, negatively affecting a cohesive collective identity [65,208].

To reduce the ambiguity surrounding the collective identity [208], a structuring process is important because it defines what characteristics are significant [210,211] and clarifies the underlying meanings from which the members of this system act. Therefore, an identity prototype is particularly important since it answers the questions “What are you doing?” and “How tight is the manifestation of your identity according to the ideal shared conceptualized image?” For example, Paula is aware that they are a benchmark through which companies measure themselves, with many regularly requesting their guidance on how to approach and deploy sustainability. In this regard, they build awareness, inform, and educate.

Since entrepreneurs engaging CBM are prone to alienating their individual entrepreneurial identities to form a shared collective identity to move forward with business requirements, conformity is particularly relevant when CBM is enacted. Insofar as an EI is created through socially constructed interactions, both the EI and stakeholders’ expectations coexist in alignment [76]. Thus, we propose the following:

Proposition 6.

The relationship between shared collective identity and CBM performance is moderated by an EI prototype.

Finally, this theoretical conceptualization recognizes a feedback loop between the pursuit of a sustainable venture and the individual set of goals and personal identities. Considering that every business evolves with competitive changes or disruptive events in technology or industries, changes are prone to occur either inside or outside the firm [101]. Hence, new information may induce individuals to update their cognitions and may thus change their conceptions about the best strategy to achieve goals as part of their learning and evolutionary adjustment behaviors [212,213].

Throughout the growth of the business, different identities are manifested (business, managerial, personal, and social, among others), and each one of them has different functions within the system. The manifestation of these identities can potentially generate new conflicts or states of “detachment/misalignment” in relation to the previously developed collective identity. In this way, our model proposed in Figure 1 leaves open the possibility of a permanent conflict through a feedback loop, but at the same time, there is also a continuous resolution, given the maturity of the conflict that lies in the disposition of those involved.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

5. Discussion

Based on prior studies, we developed a theoretical framework underscoring the mutual influence between EI and CBM. In light of our findings, it seems likely that how and why entrepreneurs select certain business models may provide invaluable insights in future efforts to investigate EI. To the extent the framework presented here encourages such interaction, it may offer useful contributions to ongoing research. The logic underlying the framework presented in this paper can be summarized as follows: (1) in essence, identity is a provisional state that is prone to change through social interactions; (2) this transitory state is molded to fit group membership and achieve a sense of social pertinence; and (3) through this endless construction process, key outcomes of the entrepreneurial process can be achieved. The framework developed in this paper reflects this reasoning and is based on a large body of research. This framework and the propositions it suggests offer several potential contributions to the subfield of sustainable entrepreneurship and EI.

The relevance of this rationale lies in bridging research on sustainable circular business model innovation and entrepreneurial identity construction based on psychological identity conflict literature to better explain why, how, and when EI is under a dynamic system of identities and how goals constantly evolve when pursuing CBM. Thus, this study contributes to the literature of EI by narrowing the context [214], which is particularly relevant in CBM when social interactions are the core of the conceptual logic of managerial functioning.

The specific mode of theorizing developed in this study is based on the shift between a static conceptualization of EI and its evolution into a dynamic system. Traditionally, studies about EI using social identity theory examine the identity as a system that is under a state of equilibrium, and the influential aspects affecting it are somehow balanced with each other. Our theoretical model instead conceptualizes EI in a CBM structure as a system under constant evolution as incumbents’ identities push the system toward a new equilibrium (e.g., supra-identity). To do so, we put special emphasis on the supra-organizational level of the entrepreneurial venture and its impact on EI. Essentially, we remarked that some elements beyond the organization are relevant for the construction of the EI since CBM generates a complex interconnected system that conjointly constructs and reconstructs EI. This in turn recognizes that causal psychological mechanisms (perception, cognition, affects, learning, motivation, attachment) are relevant for EI construction. As a consequence, the traditional features of the EI (such as clarity and coherence) are questioned by framing them in a CBM context to re-conceptualize upon the antecedents behind the construction of identity (e.g., cognitive and affective commitment for a stable and ongoing business circularity), solving the inconsistencies evidenced by prior theories.

6. Implications and Future Research

The approach that we took in this paper focused on how entrepreneurs, while trying to pursue CBM, construct new identities for themselves in collaboration with stakeholders. This particular approach provides fertile territory for integrating different conceptualizations of identity—namely, the conception of identity as a process with the notion of identity as a property [92]. In developing our model, we attempted to show not only the process of transforming an individual identity into a shared collective identity [204,215] but also how that integration occurs. Specifically, we combined determinants of maturity, disidentification, and security derived from the identity conflict literature and specified how they together impact initial identities and goals to achieve a working consensus [1,73,216]. Thus, we believe our work highlights that the connection between collective cognitions and team cohesion has significant potential for both theory development and empirical research.

A potential implication of our work involves the specification of varieties of performance outcomes that can be considered a success under CBM settings. Scholars have recognized that entrepreneurs can be considered successful based not only on financial incomes [217] but also on aspects such as symbolic capital and social recognition. However, little existing research on entrepreneurship has provided theoretical specifications for when and how entrepreneurs are driven by these nonmonetary benefits as core parts of their identities. We addressed this gap by defining the variety of performance outcomes (i.e., social and economic performance) that entrepreneurs seek to achieve through CBM, and thus our model extends the traditional notion of entrepreneurs [1]. In doing so, we contribute to addressing a basic question in the field of sustainable entrepreneurship: how do variables pertaining to entrepreneurs’ identities ultimately influence various aspects of new venture success (e.g., performance, sustainability, firm growth in sales, profits, employment)? The present framework helps answer this complex question by suggesting that an identity prototype may be one potential moderator between individual-level and firm-level variables. Specifically, the more an entrepreneur and his or her stakeholders share similar cognitive structures that parsimoniously represent a CBM prototype, the more an organic system of value creation will be captured [160,161].

Our model also extends efforts to investigate EI through the lens of social constructivism [9,218]. Recent studies have highlighted the need to study entrepreneurial activity as a socio-reflective representation [219,220,221]. This stream points to the constant tension that entrepreneurs present, such as developing a disruptive firm or pursuing the normative construction of a business venture that seeks to increase income [117,222,223]. While entrepreneurship is filled with heterogeneity [224,225], a recent literature review noted that EI tends to be centered on its antecedents, but the theoretical foundations underlying how venture outcomes also interact with the individual self are still scarce [92,226]. As a result, it seems essential for future research to include not only the development of collective identities for the purpose of enacting CBM but also how interconnected goals, individuals’ identities, and subsequent outcomes are related in a dynamic process [218,227]. By paying attention to the ongoing nature of identity and its interaction with entrepreneurs and stakeholders, the framework presented here may facilitate progress toward this goal [92,223].

Another implication of this work concerns the examination of the requirements of the negotiation process. We offer foundations for further studies so they can dig into identity loss and role or group exit, which have not been covered in the literature [92]. We propose that EI influences others beyond the focal entrepreneur [228,229], and thus we address a current gap [14]. Indeed, we argue that entrepreneurs must play a proactive role in shaping the system to comply with CBM boundaries. CBM establishes the structure and frame of a business using a holistic environmentally friendly approach; hence, it encourages a sense of community and unity, which in turn influences the focal business’s core concepts and what goals have to be pursued accordingly. In this regard, the suggested theoretical framework enables scholars to study the impact that CBM has on organizational direction in a way that is consistent with existing theories of leadership and/or organizational development. Future studies could explore the path through which identity negotiation and malleability could lead to entrepreneurs’ identity loss and the role played by identity boundaries in this regard. The concept of identity malleability refers to the degree of openness to adjusting certain facets of identity to meet the demands of a certain situation [230,231,232,233,234].

A final implication of this work relates to the proposed process of a feedback loop. This process adds a theoretical link between vulnerability and identity. As we mentioned, a central tenet of CBM is that entrepreneurs have to constantly self-verify their identities while interacting with stakeholders. This feature, in turn, highlights entrepreneurs’ preparedness for negotiation over a potentially questionable identity if stakeholders misconceive the perceived signals sent by entrepreneurs about their identities. Considering that CBM plays a critical role in creating and organizing businesses but business models are characterized by abstractness, how individuals communicate boundary objects [31] may contribute to individuals’ ability to understand these abstract concepts while enhancing coherence [34].

Given the tacit benefits of having a positive predisposition to negotiate, agreeableness as a personality trait describing a person’s ability to put other people’s needs above their own appears to have special importance for several aspects of the EI construction process in CBM. As such, it is important to call attention to the potential downside of identity malleability. In fact, psychological research has suggested that overly flexible negotiations may prove detrimental to EI and entrepreneurs’ efforts to launch successful new ventures in several different ways. For instance, strong agreeableness can lead entrepreneurs to prematurely accept potential micro-identities and to proceed with developing these apparent micro-identities even in the absence of a systematic feasibility analysis. This, in turn, may lead entrepreneurs to develop premature social images with respect to social expectations and social acceptance that are not optimal reflections of their images. Further, having a positive predisposition toward negotiation may increase entrepreneurs’ susceptibility to contingencies that can prove quite costly to both themselves and their ventures, such as drastic business-model changes [235,236,237]. Increased susceptibility to these or other contextual factors can potentially be damaging for new ventures. Thus, future studies can explore the role of personality traits not only in the selection of business models but also in how entrepreneurs negotiate their identities with stakeholders.

7. Conclusions

Within this study, we developed the idea that essential aspects of EI (such as what entrepreneurs consider important and prefer to happen) must be validated by stakeholders in order to operate under the CBM logical structure, complementing recent studies about the motives that drive circular entrepreneurs to operate [69] and how and when the process of stakeholder identification and enrolment occurs [25]. Considering that collaboration in CBM is an essential ingredient due to the complexity, risk, and uncertainties involved [51], the shaping of EI by ongoing structures of social relations set the territory for identity conflicts to emerge. These conflicts may be caused by contradictory expectations, pre-settled goals, values, and beliefs, among other aspects that generate tension. Accordingly, we conceptualized the identity negotiation process as a new shared collective entrepreneurial identity that reflects the functionality of the CBM system as a whole. We did so by proposing a multi-stage process whereby the identities of conflicting parties change, enabling the emergence of a new supra-identity conducted from a harmonious collectivity. This approach bridges research on EI and stakeholder identification and CBM. Thereby we add new insights about the EI construction process that can be valuable to the literature that has tended to adopt a holistic approach in terms of social systemic functioning (i.e., business ecosystem).

Even though we followed relevant studies about theoretical contributions and construct clarity [214,238], we acknowledge that the proposed theoretical model, as with every theory, is an abstraction and simplification of reality. As a consequence, several limitations emerge. For example, since we centered the study of identity on a circular approach, we recognize that it in no way mitigates the inherence of stakeholders in other industries for identity construction. Further, we illustrated the model using Paula Castro’s venture, but a more robust empirical exercise is required for a more comprehensive acceptance of this framework. Accordingly, it is hoped that this article prompts a fruitful line of research and debate that sharpens our understanding of circular entrepreneurs’ identity construction processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.; validation, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; formal analysis, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; investigation, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; resources, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; visualization, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; supervision, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; project administration, C.P., F.R. and J.H.; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Agency for Research and Development (ANID)/Scholarship Program/DOCTORADO BECAS CHILE/2021-21211680.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Castro for reading the manuscript and verifying the accuracy of our account of her lived experience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fauchart, E.; Gruber, M. Darwinians, Communitarians, and Missionaries: The Role of Founder Identity in Entrepreneur-ship. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarasvathy, S.D. Causation and Effectuation: Toward a Theoretical Shift from Economic Inevitability to Entrepreneurial Contingency. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, P.-S.; Shih, L.-H. Effective environmental management through environmental knowledge management. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 6, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Konietzko, J.; Baldassarre, B.; Brown, P.; Bocken, N.; Hultink, E.J. Circular business model experimentation: Demystifying assumptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 122596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.B. “Who is an Entrepreneur?” Is the Wrong Question. Am. J. Small Bus. 2016, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.B. What are we talking about when we talk about entrepreneurship? J. Bus. Ventur. 1990, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M.; Zietsma, C.; Saparito, P.; Matherne, B.P.; Davis, C. A tale of passion: New insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y. Developing optimal distinctiveness: Organizational identity processes in new ventures engaged in business model innovation. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C.M.; Harrison, R. Identity, identity formation and identity work in entrepreneurship: Conceptual developments and empirical applications. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 28, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mok, A.; Morris, M.W. Managing Two Cultural Identities. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 38, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S.D.; Dew, N.; Read, S.; Wiltbank, R. Designing Organizations that Design Environments: Lessons from Entrepreneurial Expertise. Organ. Sci. 2008, 29, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoang, H.; Gimeno, J. Becoming a founder: How founder role identity affects entrepreneurial transitions and persistence in founding. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navis, C.; Glynn, M.A. Legitimate Distinctiveness and the Entrepreneurial Identity: Influence on Investor Judgments of New Venture Plausibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 479–499. [Google Scholar]

- Mmbaga, N.A.; Mathias, B.D.; Williams, D.W.; Cardon, M.S. A review of and future agenda for research on identity in entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Marchionne, F. Market opportunities and owner identity: Are family firms different? J. Corp. Fin. 2012, 18, 476–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Nason, R.S.; Nordqvist, M.; Brush, C.G. Why Do Family Firms Strive for Nonfinancial Goals? An Organizational Identity Perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, C.; Mangematin, V.; Geoghegan, W.; Fitzgerald, C. University technology transfer offices: The search for identity to build legitimacy. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 421–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watson, A.; Dada, O.; Grünhagen, M.; Wollan, M.L. When do franchisors select entrepreneurial franchisees? An organizational identity perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5934–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachary, M.A.; McKenny, A.F.; Short, J.C.; Davis, K.M.; Wu, D. Franchise branding: An organizational identity perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navis, C.; Glynn, M.A. How New Market Categories Emerge: Temporal Dynamics of Legitimacy, Identity, and Entrepreneurship in Satellite Radio, 1990–2005. Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 439–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontikes, E.; Barnett, W.P. The Coevolution of Organizational Knowledge and Market Technology. Strat. Sci. 2017, 2, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]