Developing a Comprehensive Assessment Model of Social Value with Respect to Heritage Value for Sustainable Heritage Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

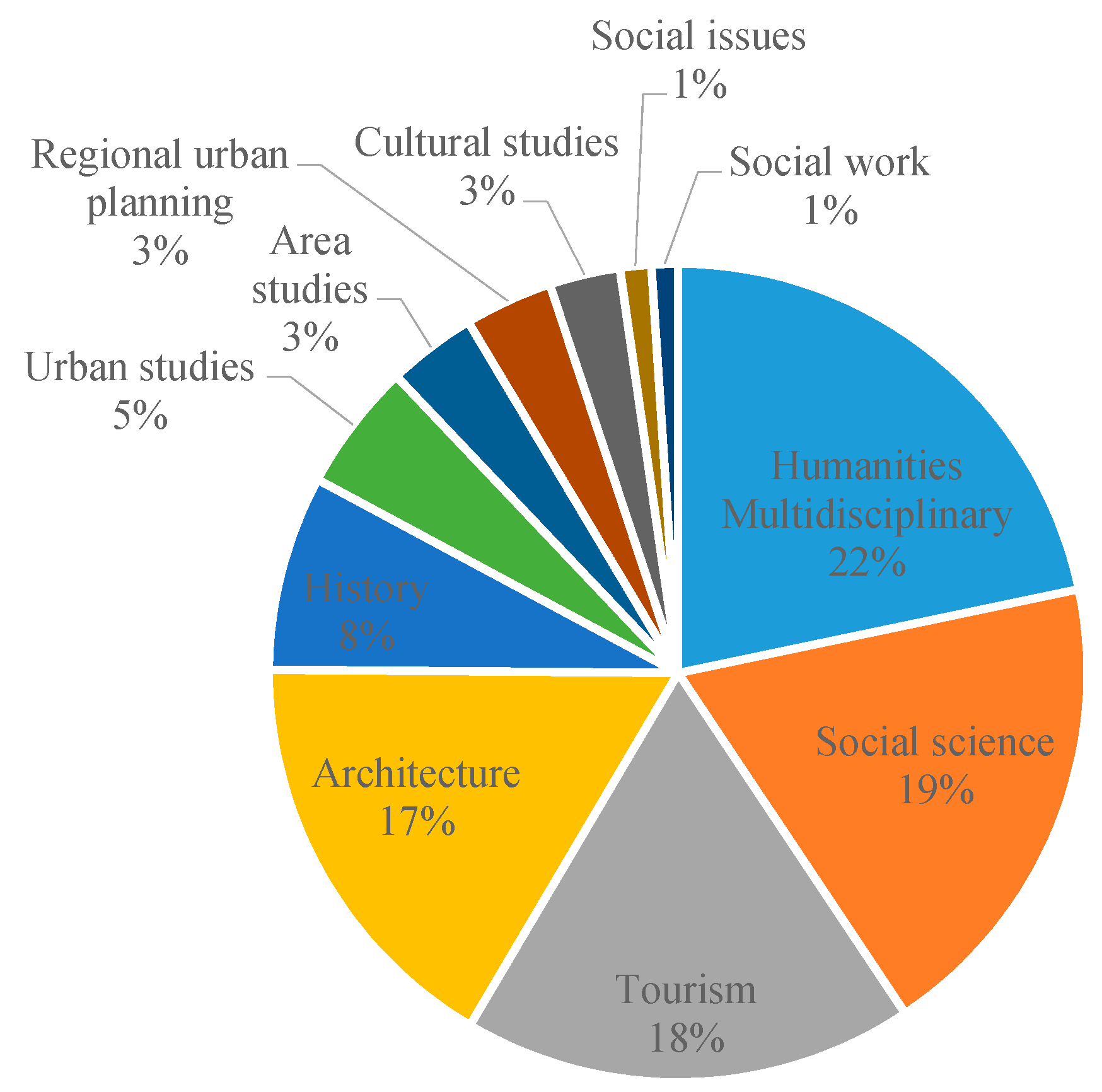

2. The State of the Art in Social Value of Cultural Heritage in China

2.1. Theoretical Research on the Heritage Value for Cultural Heritage

2.2. Previous Research on the Evaluation of Heritage Value

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Framework

- Conceptual framework

- Questionnaire survey

- Step 1. Literature was collected from a variety of sources through various methods, and the indicators that influence social value were identified, and their relationships defined as a series of hypotheses. The sources include Principles for the Conservation of Heritage in China and the 13th five-year plan (2016–2020); previous studies on evaluating heritage value; doctoral dissertations on Chinese historical districts; previous studies on heritage tourists applying conceptual frameworks.

- Step 2. A conceptual framework was constructed based on the influencing indicators and the hypotheses.

- Step 3. A questionnaire was developed to test the clarity and application of the proposed theoretical framework on social value, by attempting to understand and correlate people’s cognitions of social value with the different influencing indicators and hypotheses; the questionnaires on the social value evaluation indicators were conducted in the four case study canal towns of Nanyang, Wuzhen, Tongli and Nanxun.

- Step 4. Data was collected from questionnaire surveys distributed to each of the four historical canal town. The results of the questionnaire were analysed and the weights of the influencing factors of social value calculated and tested to verify the relationships between the indicators of social value.

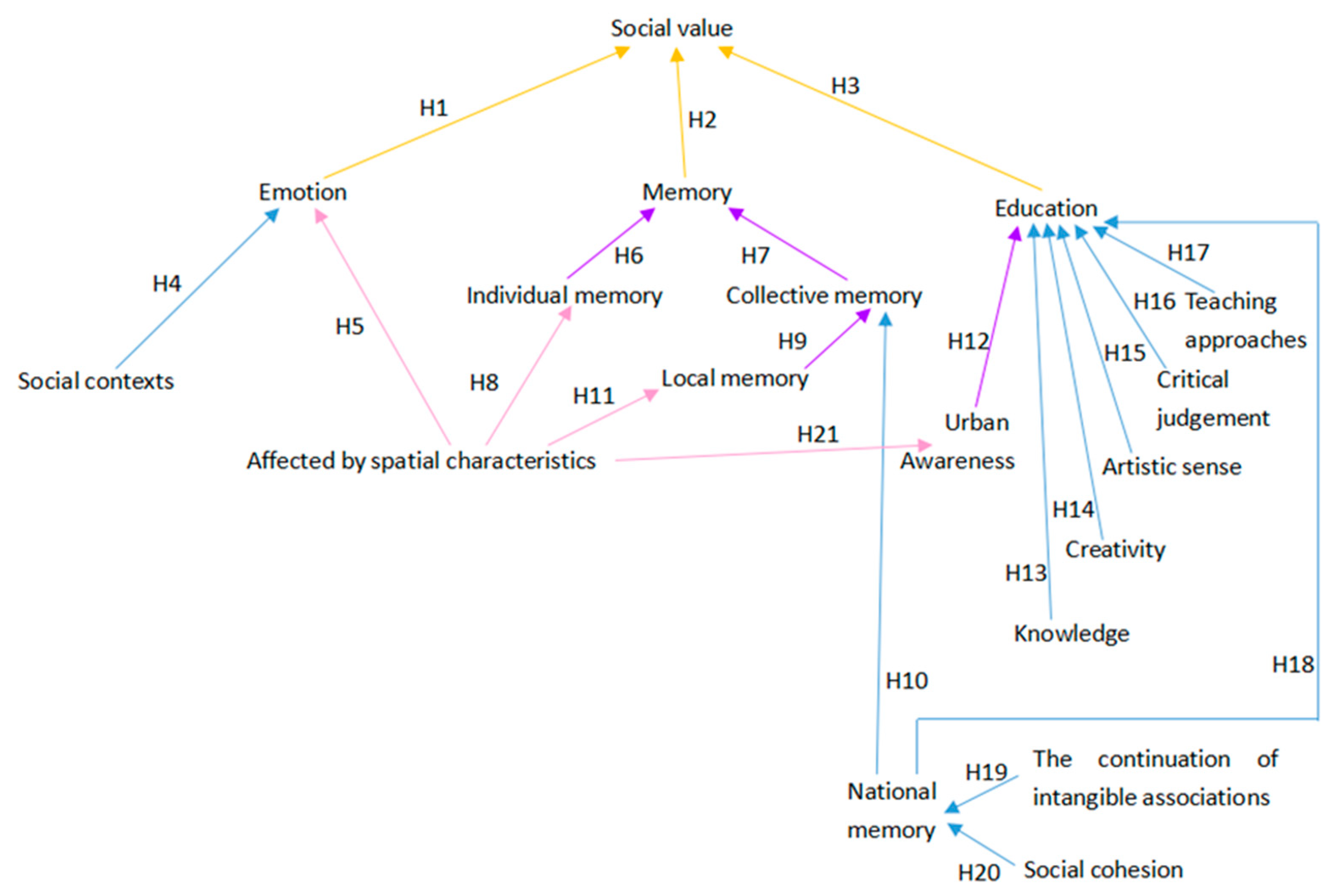

3.2. Construction of Conceptual Framework on the Evaluation of Social Value

3.2.1. Identification of Indicators Affecting Social Value

3.2.2. Theoretical Hypotheses for Conceptual Framework

“Social value is that which society derives from the educational benefit that comes from dissemination of information about a heritage site, the continuation of intangible associations and the social cohesion it may create”.[7]

3.3. Questionnaire Development

3.3.1. The Process of the Questionnaire Survey

3.3.2. Developing Questions to Theoretical Hypotheses

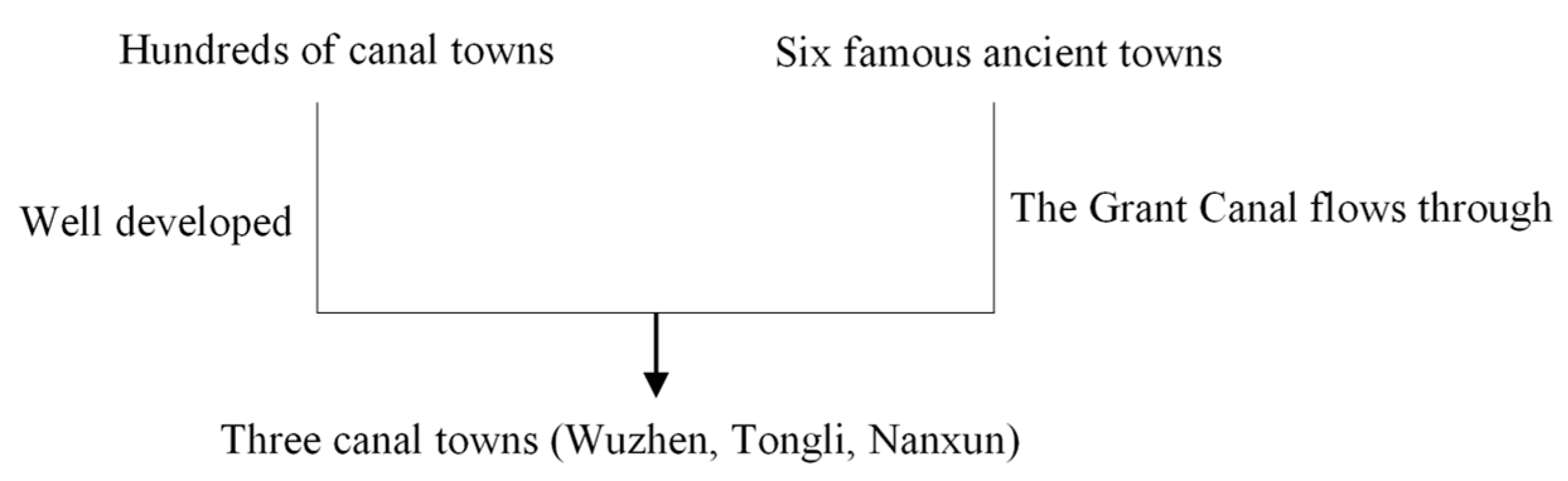

3.4. The Selection of Case Study

4. Case Studies: The Ancient Canal Towns

4.1. Overview of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal and the Canal Towns

4.1.1. Overview of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal

4.1.2. Overview of the Canal Towns

4.2. Basic Analysis on the Questionnaire Survey Data

4.2.1. The Distribution of Surveyed Participants

4.2.2. Reliability and Validity Test of Questionnaire Survey Data

4.3. Questionnaire Data Analysis of Theoretical Hypotheses

4.4. Hypotheses Test Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, L.; Yu, X. A summary of China’s researches on the protection and utilization of cultural heritage. Tour. Trib. 2004, 19, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Olukoya, O.A.P. Framing the Values of Vernacular Architecture for a Value-Based Conservation: A Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Song, X. An analysis report on the development of world cultural heritage tourism in China. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2018, 4, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y. Building a conceptual framework: Philosophy, definitions and procedure. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Han, J. The research review of China world heritage in recent dacade. World Herit. Forum 2009, 1, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS China. Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China; ICOMOS: Xi’an, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. Evaluation on Values of Historic Buildings-Case Study: Ancient Residences in Suzho. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing Agriculture University, Nanjing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Rollo, J.; Esteban, Y.; Jones, D.S.; Tong, H.; Mu, Q. Social value: Challenges of conserving cultural heritage in China, paper presented to Architecture. In AMPS 2018: Tangible-Intangible Heritage (s)—Design, Social and Cultural Critiques on the Past, the Present and the Future, Proceedings of the AMPS Conference, London, UK, 13–15 June 2018; AMPS (Architecture, Media, Politics, Society): London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS China. Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Crisis and plight of protection of historically and culturally famous cities in China. J. Shanghai Norm. Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2012, 41, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor Pérez, A.; Barreiro Martínez, D.; Parga-Dans, E.; Alonso González, P. Democratising Heritage Values: A Methodological Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Zhang, Y. The development of Shanghais urban conservation and consideration of the conservation of Chinas historic cites. Urban Plan. Forum 2005, 155, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, A.V.; Manum, B. Distance, accessibilities and attractiveness; urban form correlates of willingness to pay for dwellings examined by space syntax based measurements in GIS. J. Space Syntax. 2016, 6, 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Onecha, B.; Dotor, A.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C. Beyond Cultural and Historic Values, Sustainability as a New Kind of Value for Historic Buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. World Heritage: Defining the outstanding universal value. City Time 2006, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S. Hierarchical value map of religious tourists visiting the Vatican City/Rome. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.; Orr Scott, A.; Viles, H.A. Reconceptualising the relationships between heritage and environment within an Earth System Science framework. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 10, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J. Cultural Evolution and Value Collision in Urban Historic Heritage Conservation: Tension among Aesthetic Modernity, Instrumental Reason and Tradition. Ph.D. Thesis, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Lei, D. Value composition of historical building and economic factors of the its preservation. J. Tongji Univ. Soc. Sci. Sect. 2009, 20, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, D. Economics and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ruijgrok, E.C.M. The three economic values of cultural heritage: A case study in the Netherlands. J. Cult. Herit. 2006, 7, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Zheng, Z.; Tian, D.; Zhang, R.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Resident-Tourist Value Co-Creation in the Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism Context: The Role of Residents Perception of Tourism Development and Emotional Solidarity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, C.; Ingham, J.; Tonks, G. Identifying heritage value in URM buildings. SESOC J. 2009, 22, 16–28. [Google Scholar]

- Vakharia, N.; Vecco, M.; Srakar, A.; Janardhan, D. Knowledge centricity and organizational performance: An empirical study of the performing arts. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1124–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q. World Heritage, Archaeological Tourism and Social Value in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Barcelona University, Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, B. The value of ancient buildings and the collection of their materials. Urban Constr. Arch. Manazine 2006, 1, 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R.; Avrami, E. Heritage values and challenges of conservation planning. Manag. Plan. Archaeol. Sites 2002, 3, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam, L. The contingent valuation method: A review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2004, 24, 89–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydland, L.; Grahn, W. Identifying heritage values in local communities. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2012, 18, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, O.; Maisonnave, H.; Beyene, L.; Henseler, M.; Velasco, M. The Economic Benefits of Investing in Cultural Tourism: Evidence from the Colonial City of Santo Domingo; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Déom, C.; Valois, N. Whose heritage? Determining values of modern public spaces in Canada. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 10, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogollón, J.; Duarte, P.; Folgado-Fernández, J. The contribution of cultural events to the formation of the cognitive and affective images of a tourist destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit, R.K.; Mishra, S.A. Space syntax spproach for analyzing crime preventive urban design: Concept review. J. Adv. Res. Constr. Archit. Eng. 2014, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Erdugan, C.; Araz, A. The Cognitive, Emotional and Behavioral Indicators of Dispositional Gratitude in Close Friendship: The Case of Turkey. Psikol. Çalışmaları Stud. Psychol. 2019, 4, 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, O.; Nance, D. “Something Born of the Heart”: Culturally Affiliated Illnesses of Older Adults in Oaxaca. Issues Mental Health Nurs. 2019, 41, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Motoki, K.; Nouchi, R.; Kawashima, R.; Sugiura, M. Does Incidental Pride Increase Competency Evaluation of Others Who Appear Careless? Discrete Positive Emotions and Impression Formation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brunyé, T.T.; Mahoney, C.R.; Augustyn, J.S.; Taylor, H.A. Emotional state and local versus global spatial memory. Acta Psychologica 2009, 130, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, R.M.; Sarah, M.E.S.; Elizabeth, A.K. Positive emotion enhances association-memory. Emotion 2019, 19, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, M. On Collective Memory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.J.; Maki, W.S. Characteristics of spatial memory in pigeons. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 1983, 9, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Shaver, P. Individual differences in emotional complexity: Their psychological implications. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 687–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaeva, E.; Kamenetsky, E. Influence of historical memory on the dynamics of social tension. In International Session on Factors of Regional Extensive Development (FRED 2019); Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 540–554. [Google Scholar]

- Chris, M.F.; Jordan, D.; Stefan, K. Psychophysiological evidence for the role of emotion in adaptive memory. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 925–933. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, P. The memory of the national and the national as memory. Latin Am. Perspect. 2015, 42, 92–106. [Google Scholar]

- İslamoğlu, Ö.S. The importance of cultural heritage education in early ages. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 22, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirpa, K.; Anna, K. Cultural heritage education for intercultural communication. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2012, 1, 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, T. Heritage and education: A European perspective. Hague Forum 2004, 1, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. National humiliation, history education, and the politics of historical memory: Patriotic education campaign in China. Int. Stud. Q. 2008, 52, 783–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbishley, M. Pinning down the Past: Archaeology, Heritage, and Education Today; Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E. Urban freight transport and policy changes: Improving decision markers awareness via an agent-specific approach. Transp. Policy 2014, 36, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, M.; Blinge, M. Assessing knowledge and awareness of the sustainable urban freight transport among Swedish local authority policy planners. Transp. Policy 2014, 32, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliem, A.G.; Gliem, R.R. Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbachs alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales. In Proceedings of the Midwest Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Conttinuing, and Community Education, Columbus, OH, USA, 8–10 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Heritage Convention. The Grand Canal Volume I; State Administration of Cultural Heritage of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Wei, Q. Negotiation of Social Values in the World Heritage Listing Process: A Case Study on the Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal, China. Archaeologies 2018, 14, 501–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Y.; Xiao, J. Seeking a win-win resolution for heritage preservation and touriam development. City Plan. Rev. 2021, 6, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Hu, B. The formation of value system in the protection of Chinese historical and cultural heritage. J. Chongqing Jianzhu Univ. 2016, 2, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.K.; Ahmed, M.F.; Mokhtar, M.B.; Tan, K.L.; Idris, M.Z.; Chan, Y.C. Understanding intangible culture heritage preservation via analyzing inhabitants garments of early 19th century in weld quay, Malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS Australia. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance; Australia ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.C.; Stiefel, B.L. (Eds.) Human-Centered Built Environment Heritage Preservation: Theory and Evidence-Based Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Hypotheses | Questions for the Hypotheses | Question Code |

|---|---|---|

| H5 | Do you agree that emotion is affected by the street pattern building form and sense of place of the town? | Q1 |

| H8 | Do you agree that individual memory is affected by the street pattern and built form of the town? | Q2 |

| H11 | Do you agree that local memory is affected by the street pattern and built form of the town? | Q3 |

| H21 | Do you agree that street pattern and built form contributes to a sense of place of the town? | Q4 |

| H6 | Do you agree that individual memory influences memory? | Q5 |

| H7 | Do you agree that collective memory influences memory? | Q6 |

| H9 | Do you agree that local memory influences collective memory? | Q7 |

| H12 | Do you agree that cultural heritage can develop a sense of a sense of place? | Q8 |

| H4 | Do you agree that emotion is affected by social context? | Q9 |

| H10 | Do you agree that national memory influences collective memory? | Q10 |

| H13 | Do you agree that an awareness of cultural heritage can inspire and develop knowledge? | Q11 |

| H14 | Do you agree that an awareness of cultural heritage can inspire and develop creativity? | Q12 |

| H15 | Do you agree that cultural heritage can inspire and develop artistic awareness? | Q13 |

| H16 | Do you agree that cultural heritage can support and develop critical judgement? | Q14 |

| H17 | Do you agree that cultural heritage can enhance and develop teaching approaches? | Q15 |

| H18 | Do you agree that national memory influences education? | Q16 |

| H19 | Do you agree that national memory creates the continuation of intangible associations? | Q17 |

| H20 | Do you agree that national memory creates social cohesion? | Q18 |

| H1 | Do you agree that emotion influences social value? | Q19 |

| H2 | Do you agree that memory influences social value? | Q20 |

| H3 | Do you agree that education influences social value? | Q21 |

| Town Name | Wuzhen | Tongli | Nanxun |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Located in Tongxiang County, Jiaxing City of Zhejiang Province, 140 km from Shanghai | Located in Suzhou City of Jiangsu Province, 80 km from Shanghai | Located in Huzhou City of Zhejiang Province, 120 km from Shanghai |

| Population | 60,000 | 94,000 | 58,000 |

| Area | 6.8 square kilometres | 8.3 square kilometres | 4.18 square kilometres |

| Architecture features | Waterfront residence, White wall and black roof | Garden house with Chinese classical private garden | Ming and Qing dynasties building style |

| Heritage reputation | A national 5A scenic area | A national 5A scenic area | A national 4A scenic area |

| Heritage features | 1 national heritage unit; 2 provincial heritage units | 1 national heritage unit; 5 provincial heritage units; 4 city-level heritage units | 1 national heritage unit; 3 provincial heritage units |

| Planning features | The ancient town centre is dotted with buildings, and the water-network is relatively dense. | There are five lakes in the town. | The streets and rivers ‘branch’ in the town, and the ancient town centre is dotted with buildings. |

| Planning pictures |  |  |  |

| Town | Residents | Tourists | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanyang | 40 | 35 | 75 |

| Wuzhen | 45 | 42 | 87 |

| Tongli | 33 | 45 | 78 |

| Nanxun | 39 | 45 | 84 |

| Total | 157 | 167 | 324 |

| Demographic Characteristics | Options | Residents | Tourists | Total | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 75 | 90 | 165 | 50.9 |

| Female | 82 | 77 | 159 | 49.1 | |

| Age | 18–19 | 2 | 19 | 21 | 6.5 |

| 20–29 | 7 | 58 | 65 | 20.0 | |

| 30–39 | 31 | 47 | 78 | 24.1 | |

| 40–49 | 39 | 32 | 71 | 21.9 | |

| Above 50 | 78 | 11 | 89 | 27.5 | |

| Occupation | Office white collar | 9 | 48 | 57 | 17.6 |

| Blue collar | 33 | 28 | 61 | 18.9 | |

| Academic | 2 | 11 | 13 | 4.0 | |

| Government official | 18 | 20 | 38 | 11.7 | |

| University student | 0 | 38 | 38 | 11.7 | |

| Other | 95 | 22 | 117 | 36.1 | |

| Education level | Less than a high school diploma | 37 | 4 | 41 | 12.6 |

| High school degree or equivalent | 88 | 41 | 129 | 39.8 | |

| Some college, no degree | 29 | 25 | 54 | 16.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree (e.g., BA, BS) | 3 | 76 | 79 | 24.4 | |

| Master’s degree (e.g., MA, MS, MArch) | 0 | 19 | 19 | 5.9 | |

| Doctorate (e.g., PhD) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

|---|---|

| 0.818 | 39 |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.796 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 1822.150 |

| df | 496 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| Question Code | Average Value of Four Towns | Total Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanyang | Wuzhen | Tongli | Nanxun | ||

| Q1 | 4.9 | 4.93 | 4.9 | 4.96 | 4.92 |

| Q2 | 4.87 | 4.92 | 4.91 | 4.88 | 4.9 |

| Q3 | 4.92 | 4.92 | 4.9 | 4.89 | 4.91 |

| Q4 | 4.89 | 4.91 | 4.92 | 4.93 | 4.91 |

| Q5 | 4.87 | 4.88 | 4.87 | 4.91 | 4.88 |

| Q6 | 4.88 | 4.86 | 4.87 | 4.85 | 4.86 |

| Q7 | 4.91 | 4.89 | 4.89 | 4.88 | 4.89 |

| Q8 | 4.92 | 4.88 | 4.87 | 4.88 | 4.89 |

| Q9 | 4.9 | 4.89 | 4.91 | 4.93 | 4.91 |

| Q10 | 4.89 | 4.89 | 4.91 | 4.91 | 4.9 |

| Q11 | 4.94 | 4.93 | 4.92 | 4.94 | 4.93 |

| Q12 | 4.89 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.93 | 4.91 |

| Q13 | 4.92 | 4.91 | 4.91 | 4.9 | 4.91 |

| Q14 | 4.93 | 4.95 | 4.95 | 4.94 | 4.94 |

| Q15 | 4.95 | 4.97 | 4.96 | 4.93 | 4.95 |

| Q16 | 4.96 | 4.93 | 4.96 | 4.96 | 4.95 |

| Q17 | 4.91 | 4.9 | 4.92 | 4.9 | 4.91 |

| Q18 | 4.9 | 4.87 | 4.88 | 4.89 | 4.88 |

| Q19 | 4.92 | 4.94 | 4.9 | 4.93 | 4.92 |

| Q20 | 4.95 | 4.93 | 4.94 | 4.95 | 4.94 |

| Q21 | 4.91 | 4.92 | 4.93 | 4.92 | 4.92 |

| Questionnaire Survey Results | Test Results of Theoretical Hypotheses | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Attitude of Participants | Hypotheses Code and Path | Hypothesis Supported |

| Q19 | Positive | H1: Emotion → Social value | Yes |

| Q20 | positive | H2: Memory → Social value | Yes |

| Q21 | positive | H3: Education → Social value | Yes |

| Q9 | positive | H4: Social contexts → Emotion | Yes |

| Q1 | positive | H5: Spatial characteristics → Emotion | Yes |

| Q5 | positive | H6: Individual memory → Memory | Yes |

| Q6 | positive | H7: Collective memory → Memory | Yes |

| Q2 | positive | H8: Spatial characteristics → Individual memory | Yes |

| Q7 | positive | H9: Local memory → Collective memory | Yes |

| Q10 | positive | H10: National memory → Collective memory | Yes |

| Q3 | positive | H11: Spatial characteristics → Local memory | Yes |

| Q8 | positive | H12: Urban awareness → Education | Yes |

| Q11 | positive | H13: Knowledge → Education | Yes |

| Q12 | positive | H14: Creativity → Education | Yes |

| Q13 | positive | H15: Artistic sense → Education | Yes |

| Q14 | positive | H16: Critical judgement → Education | Yes |

| Q15 | positive | H17: Teaching approaches → Education | Yes |

| Q16 | positive | H18: National memory → Education | Yes |

| Q17 | positive | H19: The continuation of intangible associations → National memory | Yes |

| Q18 | positive | H20: Social cohesion → National memory | Yes |

| Q4 | positive | H21: Spatial characteristics → Urban awareness | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Rollo, J.; Esteban, Y.; Tong, H.; Yin, X. Developing a Comprehensive Assessment Model of Social Value with Respect to Heritage Value for Sustainable Heritage Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313373

Xu Y, Rollo J, Esteban Y, Tong H, Yin X. Developing a Comprehensive Assessment Model of Social Value with Respect to Heritage Value for Sustainable Heritage Management. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313373

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Yabing, John Rollo, Yolanda Esteban, Hui Tong, and Xin Yin. 2021. "Developing a Comprehensive Assessment Model of Social Value with Respect to Heritage Value for Sustainable Heritage Management" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313373

APA StyleXu, Y., Rollo, J., Esteban, Y., Tong, H., & Yin, X. (2021). Developing a Comprehensive Assessment Model of Social Value with Respect to Heritage Value for Sustainable Heritage Management. Sustainability, 13(23), 13373. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313373