1. Introduction

Work is one of the basic activities of human life. Its performance may take place in various conditions; however, for the work to achieve the results expected by both employers and the people performing it, it should be performed in safe conditions. The point is, therefore, to create working conditions that do not threaten physical health or human mental health. It must be remembered that improper working conditions may cause accidents at work and physical injuries. Moreover, they can lead to the frustration of even the most qualified and best-trained workers. Bad working conditions, i.e., those that are not adapted to the psychological, physiological, and social needs of a person, contribute to making mistakes, greater absenteeism, and in the long-run lead to lower productivity and satisfaction in the performed duties. In extreme cases, they are the reason for resignation from work.

The relationship between shaping working conditions and achieving the effects desired by employees and employers, including the elimination of errors made while performing work, are discussed in the literature. In this context, it is indicated, for example, that a change in working procedures leads to a change in the requirements for employees. When changing these procedures, and the related changes in working conditions, attention is not always paid to the consequences for workers and their health [

1]. Only those who have suffered an accident or illness in connection with their work are interested in this. This points to a conflict between the use of the means of production and their impact on humans and their work, which includes the mistakes made during work. The means of production facilitate work but can negatively affect workers and their work. It is about, for example, a working time that is too long and the influence of factors such as air pollution, noise, chemical pollution, and stress at work [

2,

3]. These conditions reduce the concentration of employees and their focus on tasks, which leads to a low level of work efficiency, including low productivity, low quality, and physical and emotional stress. All this has an impact on making mistakes at work and, consequently, on labor costs. On the other hand, e.g., effective application of ergonomics in work conditions, as stated by various authors, promotes work safety, well-being, and job satisfaction [

4,

5,

6,

7]. This leads to the minimization of mistakes made at work, an increase in the effects of work, and, as a result, promotes sustainable development.

Against this background, the changes in the economy because of the industrial revolution and the impact of COVID-19 transferred a significant part of the trade to the e-commerce sphere. This means an increased turnover value of enterprises operating in this area and generates new problems that have not been observed so far. Order picking is a particularly sensitive area in e-commerce, mainly (but not exclusively) for large entities. Order picking is largely done using human labor. This work, as already stated above, and its effects are related to the appropriate shaping of working conditions or occupational health and safety. It can be assumed that it is this area, i.e., working conditions or occupational health and safety, that cause the biggest problems (manifested, among others, by the occurrence of errors in the course of work) related to achieving the effects of work intended by entrepreneurs.

Meanwhile, when searching in the SCOPUS database, entering the phrase, “Occupational Health and Safety”, in the article title section, results in 5520 indications. The most frequently cited studies in this area include articles on bullying in the workplace [

8], job insecurity, restructuring, temporary work, a review of research on their implications that includes shaping safe and hygienic working conditions [

9], and the relationship between the architecture of EU legislation and issues such as Occupational Health and Safety [

10]. On the other hand, by entering the phrase, “Occupational Health and Safety”, and adding the phrase, “e-commerce”, no corresponding publications were found. Then, the phrase, ”working conditions”, was entered. After an initial review of the indexed literature in the SCOPUS databases, using this phrase to search the titles of articles provided 100,428 results.

We limited the analysis to articles in the area of social sciences and business, management, and accounting, due to the large excess of publications in fields such as engineering, medicine, astronomy, etc. Among the most-cited studies are those devoted to considering working conditions in a broad sense, i.e., related to both tangible and intangible elements, in particular, with the issue of remuneration for work and improvement of working conditions of the people performing it, and also taking into account aspects of environmental protection, sustainable development, and shaping the well-being of employees [

11,

12]. Considering the obtained results of the analysis, the phrase, “e-commerce”, was added to the phrase, “working conditions”, in the analysis of the literature. As a result, after an initial review of the literature indexed in SCOPUS databases, we acquired 127 results. The most frequently cited publications in this area concern new technologies that allow the emergence of new forms of work and the improvement of its accessibility, possibly leading to a narrowing of the gender gap, online platforms in the context of employment, and the use of online training systems [

13,

14,

15]. Referring to the above considerations, it was concluded that there is no research on the relationship between the creation of safe and hygienic working conditions in e-commerce enterprises and the impact of these conditions on work results in these enterprises. It was also assumed that particular attention should be paid to the area of operation of these enterprises, which is the process of picking orders. The issues of e-commerce are taken, among others, in the context of consumer behavior, including the impact of online reviews on purchasing decisions [

16]. The subject of research is also the effectiveness of the use of various sales techniques regarding, e.g., prices, discounts, and bonuses [

17].

The research presented in this article aims to find factors that determine the occurrence of errors in the order picking process and to confirm or deny the assumption that these factors largely concern employees and their working conditions. Going further, it can be said that the study aims to answer the question of what, if any, working conditions affect the occurrence of errors in the order picking process. This means that the problem of broadly understood working conditions will be raised first, not only from the perspective of occupational health and safety but also from the perspective of error (non-compliance) causes. The next Section will be devoted to the specificity of order fulfilment in e-commerce companies. The third Section of the article is devoted to research presentation. The article ends with conclusions drawn from the conducted research. The research was carried out in one company in accordance with the case-study research strategy. The prospect of the conducted research was focused on reducing the number of errors (non-conformities) in the order picking process while trying to maintain or improve working conditions.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Working Conditions

Working conditions are the result of interaction between a job, the work, the company, and an individual [

18]. An analysis of subject literature allows us to conclude that in practice we are dealing with a very enigmatic approach to the definition of working conditions, which probably prompts some authors to consider the conditions we are interested in mainly or exclusively as a sum of their components. Work conditions are thus most often considered either narrowly or broadly. In the first case, working conditions are divided into two main groups, i.e., tangible, and intangible elements, these, in turn, are distinguished into individual components. The tangible components include such physical, material, chemical, and biological elements as, for example, equipment in workplaces and workrooms, lighting, microclimate, noise, etc. The intangible elements include working time, interpersonal relations, social, and living activities [

19].

The importance of working conditions and their impact on the processes carried out in the enterprise is also evidenced by the fact that the definition of this term was coined by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (EUROFOUND) [

20]. It defines working conditions in a much broader, more comprehensive way than the division above. The EUROFOUND definition states: “working conditions refer to the conditions in and under which work is performed. A working condition is a characteristic or a combination of characteristics of work that can be modified and improved. Current conceptions of working conditions incorporate considerations of wider factors, which may affect the employee psychosomatically. Thus, a broader definition of the term includes the economic dimension of work and effects on living conditions”. EUROFOUND treats these conditions as a set of factors relating to the working environment and aspects related to the employment of an employee. This includes issues such as work organization, earnings and prospects, and job satisfaction; training, development of skills and competences, employability; health, safety, and well-being; as well as working time and work–life balance. An even better understanding of their concept of working conditions can be obtained by reading the questions posed in their research, conducted in five-year cycles since 1991. The last edition was in 2015 and each edition clarified and extended its scope [

21]. The EUROFOUND questionnaire asked questions about the following matters: working time; physical environment; work intensity; social environment; skills, discretions and other cognitive factors; forms of employment; as well as aspects related to professional life and work organization. For the purposes of this article, it is reasonable to use a broad definition of working conditions and their elements, i.e., looking at working conditions through the prism of the variables included in the EUROFOUND research.

An analysis of the subject literature also allows us to conclude that the definition of working conditions has not changed dramatically over the last dozen, or even several dozen, years [

22]. Only the scope of the issues under consideration is widening. This seems to be due to the increasing diversification of work circumstances and at the same time the impact of these circumstances on a person and the effects of their work. Increasingly, health and safety are referred to not only from the perspective of physical health but from a psychosomatic and mental perspective, hence the extension of the concept of working conditions to all factors that affect mental health, from interpersonal relationships, using CSR, to lean management (LM).

The concept of working conditions is most often defined by organizations dealing with health and safety at work and occupational hazards. One such definition is quoted above. Sometimes, the literature separates the concept of safety from working conditions. Most often, however, researchers writing about working conditions also point to work safety. If the emphasis is on safety, it usually concerns threats to physical health; if the emphasis is on working conditions, the topic is much wider. Researchers dealing with working conditions also used the working environment quality concept, separating working conditions into the sphere of physical impact and the quality of the working environment as a set of factors shaping mental health [

23]. According to many [

24], the quality of the work environment consists of many elements, including the organizational trust level, organizational fairness, and feeling supported by the organization and superiors. As usual, the reality is much more complicated, with research supporting the idea of the psychosomatic nature of human health: mental health affects physical health and vice versa. The first and essential field of interest for researchers of working conditions was the sphere of threats to occupational health and safety, i.e., the analysis of the impact of working conditions on physical health (accidents and occupational diseases). Next, the researchers focused their interest on the impact of working conditions on health, understood more broadly, not only in the physical but also in the mental sense. In the literature, however, these terms are often used interchangeably and defined for the purposes of a specific study. Today, working conditions should be equated with a broad understanding of the working environment.

The impact of a systemic drive towards improving the efficiency of process implementation on the employees’ health of merits reflection. Important research in this area is carried out in the USA and Europe. Worker health degraded earlier in the United States than in the European Union, starting in the mid-1980s and continuing to the mid-1990s, when the first forms of production organization based on the LM concept appeared in the country [

25,

26,

27]. Research conducted at the beginning of the 21st century revealed that this phenomenon reached Europe in the 1990s. [

28,

29,

30,

31]. This research identified the relationship of several major factors of working conditions that contributed to the deterioration of the health condition of employees. These factors included:

Repetitive work and its intensity;

Teamwork, the pace of work depending on the work of colleagues, and machines;

Rotating schedules,

Adherence to quality standards, sitting position [

32,

33,

34].

Therefore, a question may be raised whether it is possible to shape the broadly understood working conditions so that process efficiency improvement does not take place at the expense of the physical and mental health of employees.

Cierniak-Emerych and Golej [

35,

36] show in their research that during the implementation of 5S practices in the studied enterprises, the impact of the introduced changes on the physical and mental health of employees was not considered. The implementations were focused on improving work efficiency. The authors’ observations from the implementations of LM tools indicate that the priority of LM implementations is to improve work efficiency and focus on reducing MUDA, ignoring the simultaneous need to reduce MURI and MURA. At the same time, MURI is an excessive burden on employees. The importance of LM implementation guidelines for the health of employees is demonstrated by Bruere [

37].

Researchers [

38] show a feedback relationship between professional activity and good family relationships, having a good diet, and systematic physical training (private life, which happens outside of work). A balance between the professional and private spheres leads to well-being. It is therefore impossible to think of work as the only source of well-being, any more than you cannot associate well-being solely with your private life.

The issues of employee overload, the imbalance between work and private life and, consequently, health, the phenomenon of occupational burnout, the implementation of social functions or well-being are the subject of many studies [

38,

39]. Horgandefined burnout as “Burnout is a cunning thief that robs the world of its best and its brightest by feeding on their energy, enthusiasm, and passion, transforming these positive qualities into exhaustion, frustration, and disillusionment” [

40].

Another important context for the efficiency of process implementation by employees is their HIM (high involvement management) commitment. Bockerman, Bryson, and Ilmakunnasc [

41] indicate that engagement management practices (HIM) are generally positively and significantly related to various aspects of employee well-being. HIM is strongly associated with higher ratings of subjective well-being, including higher job satisfaction and no fatigue. These practices are also associated with a lower likelihood of an accident at work. However, exposure to HIM instruments—especially pay and performance-related training—is also associated with more short periods of absence, as it is more demanding than standard production and because multi-skilled workers overlap with each other for short absences, thus reducing the cost of replacement work.

Schulze et al. [

42] show the importance of communication through formal and informal new means of social communication and their relationship with trade unions for the improvement of working conditions.

2.2. The Specifics of E-Commerce

Online sales [

43] can be defined as activities aimed at encouraging a potential customer to purchase a good or service using an online platform. Such sales may take various forms, from online stores through classified websites and auctions to stock exchanges.

The example analyzed in this article concerns an online store with a wide range of products, from industrial products to durable food.

The specificity of e-commerce also includes customer requirements, which have three aspects. The first concerns the product itself, the second concerns the terms of delivery and the third concerns communication. The second and third areas are typical for traditional commercial relationships, which consist of suppliers and/or mail orders.

For the product, customer requirements concern:

Prices;

Completeness of the order;

Product status consistent with the product information posted on the store’s website;

No damage to the ordered products.

For delivery, they concern:

For communication, they concern:

The key point seems to be the correct completion of the order so that it is delivered on time, is complete, and does not contain damaged products. Therefore, there is a problem of proper picking and the related problem of movement damaged goods in the order picking hall. This problem may be particularly important if there are many employees and many orders, and the pace of work is fast.

An important factor shaping logistic/technological solutions in an order picking hall is the ever developing and ever more affordable automation, which is in line with the Industry 4.0 concept. Much of the order picking process can be done automatically, but most key activities are still done manually. This is due to the limitations of modern robots, their specialization, and low flexibility at an economically acceptable price.

2.3. Sustainable Development

The formula of sustainable development is relatively new. The now widely recognized version comes from 1987, from the so-called Brundtland Report, a publication released in 1987 by the World Commission on Environment and Development [

44] that introduced the concept of sustainable development and described how it could be achieved.

The main backbone of the Brundtland Commission’s definition of “sustainable development” seems to be intergenerational justice based on the idea of humanity. “Sustainable development is a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

45]. The basic and necessary ‘needs’ of humanity should be reasonably met, to which economic growth contributes. Economic growth is based on the rational use of natural resources and increasing the use of renewable resources. The concept of sustainable development is constantly evolving. In 2015, the UN adopted an agenda identifying sustainable development by identifying the objectives of this concept on a global scale. On 25 September 2015, all 193 United Nations Member States adopted Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

46]. “The heart of the 2030 Agenda is its set of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a universal set of interrelated and indivisible goals, targets and indicators balanced between the three pillars of sustainable development—social, economic, and environmental—that seek to address the global challenges we face.” [

47]. Among the objectives (SDGs) are those related to improving the efficiency of production, i.e., rational consumption of resources as well as those related to decent work and well-being of employees. These objectives are directly linked to the subject matter of the article [

46,

47].

This leads to the minimization of mistakes made at work, an increase in the effects of work, and, as a result, promotes sustainable development. The purpose of order picking is to carry out as many downloads as possible in time while meeting the conditions of decent work and well-being. These goals are contradictory; therefore, it is necessary to set standards and good practices in this respect. Harmonization of these goals may lead to an improvement in the psychophysical condition of employees and management. Avoiding overload leads to the minimization of mistakes made at work, increasing the effects of work and, consequently, contributing to sustainable development. Finally, order picking process improvements are aimed at minimizing the number of resources used.

The topic of sustainable consumer behavior is raised in [

48]. The introduction to this item synthetically introduces various contexts of consumer behavior, especially in the perspective of eco-behavior and social dilemma [

48].

3. Research Methodology

The research intention behind this article is to examine the relationship between working conditions and problems/errors occurring in the order picking process in an e-commerce enterprise. E-commerce enterprises in the B2C retail area are very diverse in terms of size, range of products, and type of products. The subject of this research is to determine the most important causes of errors in order picking. Working conditions, as a phenomenon, cause threats to order quality by their very nature and can therefore be seen as a cause of the error. This study aims to answer the question of which, if any, working conditions affect the occurrence of errors in the order picking process. This study aims to answer the question of whether and what working conditions affect the occurrence of errors in the order picking process. On this basis, a hypothesis can be made working conditions affect the main anomalies occurring in the order picking process. An anomaly is that we understand non-conformities in the completed order and the efficiency of the order completion process. The search for a universal answer on how to shape working conditions to improve the order picking process is difficult, due to varying conditions of work performance. Recommendations are therefore contextual in nature, which should be considered a research limitation.

The most appropriate research method to analyze the problem at hand is the case study analysis. This approach is based on a detailed study of an isolated case, but without making any preliminary assumptions [

49]. Case study as a research strategy uses both qualitative and quantitative research methods. Single-subject research provides a sort of statistical framework for drawing conclusions from the quantitative data of individual case studies. A case study can also be defined as a research strategy or an empirical study examining a given phenomenon in a real context [

50]. The key issue to consider when selecting an appropriate research method and process is the choice between artificially inducing an effect to confirm a hypothesis and observing the natural development of a situation to understand the source of a given phenomenon. The desire for research objectivity thus leads to applying the case study approach [

51].

The first stage of the research consisted of two months of systematic observation, from which working conditions that could affect the number of errors were identified and the risks catalogued. The non-compliance card method, derived from quality management, was used to identify the most common errors in the order picking process [

52,

53]. A summary of the results from the discrepancy cards was collected and analyzed using the Pareto–Lorenz method. In this way, the main problems in the order picking process were identified.

The next stage of the research was to determine the threat causes. The Ishikawa Diagram method was used for this part of the study. Ishikawa listed five main causes, or 5M (material, method, machine, management, and human resources) which were then supplemented with an environmental dimension. This study uses the 5M + E variant, as it seems appropriate for a search for causes in working conditions. Another reason for choosing the 5M + E method was to avoid reducing all error causes to one category—working conditions. The use of the Ishikawa method allows for a broader view of the problem.

The results of the research and the conclusions drawn from them lead to the verification of the research hypothesis, the strength of the influence of individual factors is estimated and rather vectorial. The research was realized in company X, a distributor of parts, accessories and food, the recipient of which is, among others, the Polish consumer. The company is an expert when it comes to the distribution of products of various brands and represents around 50 global producers. This poses a great challenge when it comes to the flow of goods. The company cares much about ensuring high standards of customer service and increasing sales. They estimate 80,000 parcels of goods are sent out every day. The main activity of the warehouse is based on the following processes:

Receiving goods at the warehouse;

Picking the goods out in accordance with customer order;

Shipping the goods in line with customer expectations.

Each process that takes place in the warehouse should be carried out within the appropriate time and keeping to expected quality.

The internal structure of the warehouse is divided into two parts, one for handling incoming goods, and the other for collection and shipment of goods. For handling incoming goods, we can distinguish the following processes:

Receiving goods at the warehouse;

Placing goods in the warehouse;

Exchanging goods between various company warehouses.

After receiving and arranging the goods on the warehouse shelves, the quality department checks whether these actions were performed correctly. For the shipping department, we can distinguish the following processes:

Collecting goods;

Packing goods;

Shipping goods.

The finished packages are sorted and loaded into containers, and then sent to the customer according to the order placed.

4. Research Report

4.1. Order Picking Process

Orders are generated in the system only for items that are assigned to given locations. The goods are picked up by employees following the order of shipment. Employees completing orders have a specific location and name of the goods displayed on a handheld scanner. They collect the goods and place them in plastic containers, and then transfer them to the packing station. Containers are transported by means of roller conveyors.

The containers are picked up by the packers. Each product is assigned to the container in which it is in the system. After the container is scanned at the packing station, a product list is displayed. After scanning each product, the system indicates the appropriate type of box into which the goods should be packed.

The ready shipment goes to the next roller conveyor and is transported to another place for weighing and labelling with an address.

If the package passes the weight check, and the attached label turns out to be clear (legible), the package is sent on and the code on the label directs it to a specific loading gate.

4.2. Identification of Working Conditions in the Examined Enterprise in the Context of Errors in the Picking Process

The observation indicated several elements of working conditions which may potentially affect the number of errors in the order picking process in company X. They are summarized in

Table 1.

In warehouse X, employees work in shifts. The morning shift is from 6:00 to 16:30, the night shift is from 17:30 to 4:00.

A one-off period of an employee’s activity at work is 10 h. This has obvious consequences. Employees are divided into six main brigades and each of them works according to a specific schedule in the system from Sunday to Wednesday or from Wednesday to Saturday, as well as from Monday to Friday, excluding Wednesday. Additionally, there are many types of shifts that allow part-time work (on selected 2 days of the week). Most (49) employees are employed on shifts lasting from Sunday to Wednesday because historical data shows that is when the most customer orders arrive. The order picking area is characterized by a high employee turnover. Additionally, as indicated in

Table 1, work is monotonous while at the same time it can change depending on current needs. There is often a discrepancy between the workload and the number of employees, leading to employees being moved between departments. Seemingly, this should make work less monotonous, but since employees do not get appropriate training, their work is not always conducive to reducing the number of errors. Moreover, the company has not identified a detailed training program for employees performing the picking process. The training is limited to introductory (instructional at workstations) and health and safety training.

It was also found that the remuneration system does not provide incentives, which affects employee commitment.

A key parameter of work efficiency control is the minimum number of downloads per employee per hour meter. This parameter becomes more stringent with an employee’s seniority. This approach causes employees to limit the number of activities where possible, shifting problems without eliminating them. In the case of a defective or damaged product, the employee leaves it on site, leaving the next employee to come across it and forcing them to go through an additional step of finding a satisfactory item. This measure does not reflect the impact of employee overload on work results. For such a solution, every hour is the same, while the employee works differently in the first hour of work than in the tenth hour. A low level of employee involvement was also noted, manifested by frequent and unjustified downtime. At the same time, no conscious actions were taken to increase employee involvement. Perhaps one of the reasons for this situation was the physical conditions of work, as well as aspects related to the organization of work, specific for the enterprise and including but not limited to such issues as no clear regulations regarding the turnover of damaged goods in the production hall, or the number of employees assigned to one manager exceeding the standard for management spread.

4.3. Identification of the Main Threats Related to Order Completion

After two months of observation and analysis of internal documentation, we have identified threats to delivery completion and listed them in

Table 2.

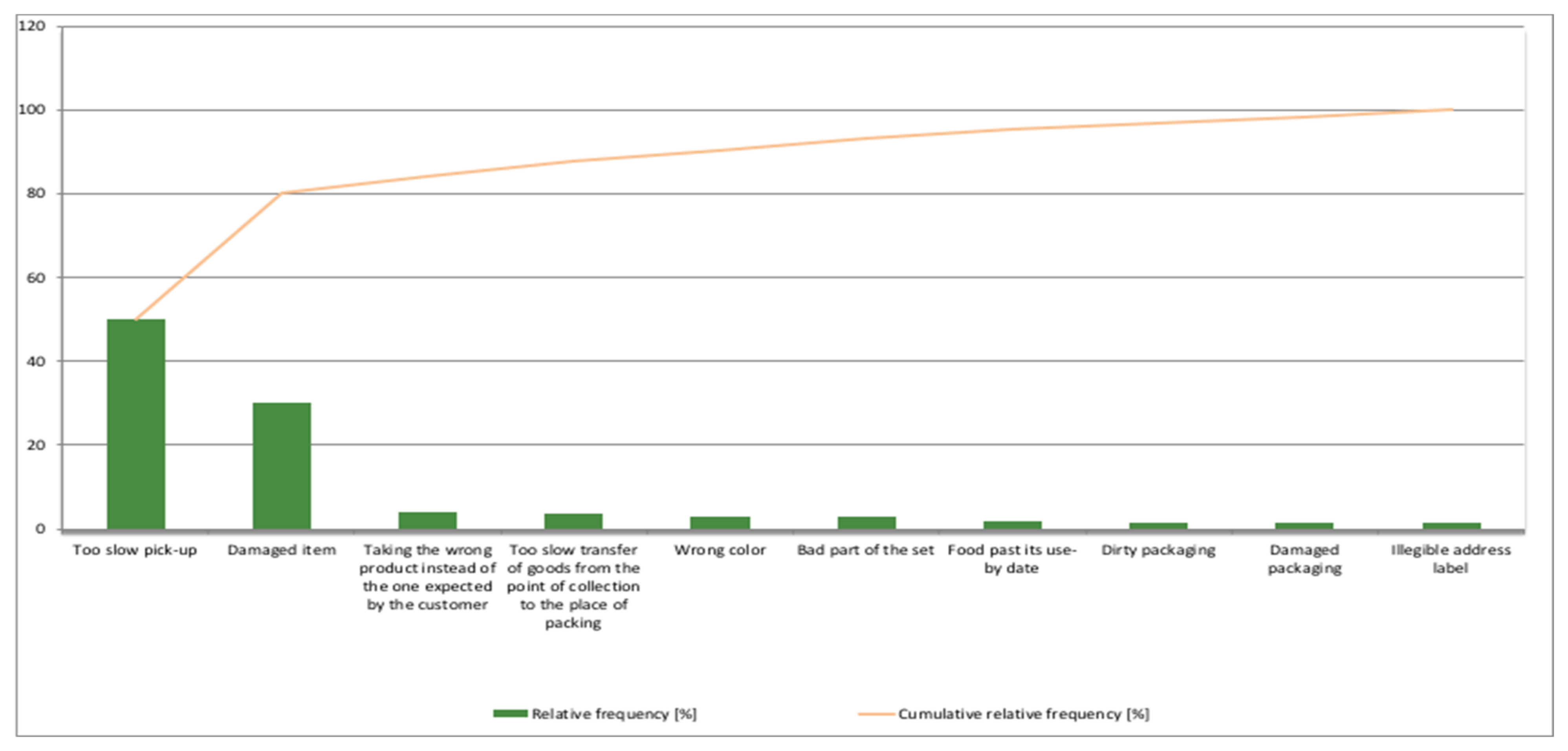

Table 2 shows the total number of anomalies for a particular anomaly, the cumulative amount of anomalies, the relative frequency, and the cumulative relative frequency expressed as a percentage.

Figure 1 is a graphic illustration of the results obtained. The results indicate that the most common anomaly is too slow pick-up and retrieval of a damaged item. These two areas will therefore be subject to a cause-and-effect analysis. The causal analysis of this phenomenon was carried out using the Ishikawa Diagram method.

The problem, however, may lie in the measurement itself and the standard being the reference for the assessment. There is a logical relationship between picking up a damaged product and too slow a pick-up. It involves the need to put the damaged item aside, which extends the order picking process.

The research conducted has shown that the most important problems in the order picking process are: goods being picked up too slowly (expected efficiency is lower than expected) and goods being damaged. These two areas will therefore be subject to a cause-and-effect analysis.

4.4. Cause-and-Effect Analysis

Two Ishikawa diagrams were prepared to analyze the possible causes of the most common anomalies: one for anomalies such as too slow goods collection and another for damaged items. From

Figure 2 it is clear that the most important reason for too slow order picking is the human factor.

The overriding reason is the high employee turnover, especially in the period of increased inflow of orders (e.g., before Christmas, when toy sales dominate). Employees are often low-skilled, not sufficiently involved in the duties entrusted to them, and take too much downtime during work. The organizational structure of the entire company is also important. There is a physical inability to control all employees because there are too many of them. Some system problems occurred as well. The closer it is to the time of order fulfilment as declared by the warehouse (the time of the scheduled shipment), the greater the distance between the collected items. The system then selects only items with the longest waiting time for the customer. There, employees are also expected to retrieve many products per hour, meaning that in order to meet these expectations, they often pay little attention to product quality. It takes less time to pick up a damaged product than to separate it in a designated container. It is recommended not to increase the expected minimum hourly retrievals for senior employees. The IT system informs the employee about the products in the order but does not indicate the optimal route for order picking.

Figure 3 shows the results of the causal analysis of damage to goods using the Ishikawa Diagram method. Damaged goods can be encountered at all stages of the process—from unloading the goods to packing. The flow of goods is constantly monitored by the scanning system. At each stage, the system shows who had previously contact with a given product.

However, there are no clear guidelines as to the method of marking the goods as damaged (not fit for sale). It is necessary to create unambiguous work instructions and train employees to carry them out. The later the product is verified, the greater the impact on the time of delivery of the product to the customer. If the product is found not suitable for sale, it should be separated from others and placed in a special container. An employee of the Quality Department should then collect all these items and transport them to a special zone, where they can be assessed and, if possible, repaired (e.g., repacking into another box if the damage is only to the packaging). When the product is released for sale again, it should be placed on the shelf again. However, if the product is not suitable, it should be disposed of. When the damaged item is already assigned to a specific order and is found out only during packing, an employee has to go search for an identical product if available, significantly extending the time of order fulfilment. The sooner the damaged item is located (preferably, separated upon receipt), the fewer working hours will be lost. In addition, many items are damaged:

Employees are prone to making mistakes due to fatigue from long and monotonous work. An important issue is warehouse lighting and variable temperature conditions in the halls, which makes it difficult to identify products, including damaged ones. These conditions extend the time of order picking.

5. Discussion

As a result of the conducted research and observations, it should be stated that too large a workload on employees leads to errors. Employees work under stress due to the productivity expected by the employer. This can lead to a burnout effect, which is imperceptible in the short term. Similar conclusions were drawn by the researchers, they stated that the use of Lean Management tools, without due attention to overloading employees, leads to accidents and deterioration of the health of employees [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Currently, the area of occupational safety is formally structured in many countries. When implementing tools to improve work efficiency, attention is also paid to work safety. It is doubtful, however, whether attention is paid to the intensity and duration of work (leading to overload) and, consequently, to the well-being of employees. The conducted research shows that the company is looking for a continuous increase in efficiency, for example by increasing the norms of the number of downloads over time along with the increase in experience. The use of these and other mechanisms of increasing work intensity is not uncommon. The well-known theories explaining long working hours and high work intensity mostly look at workers and pay less attention to employers and the wider work context that pushes to increase the workload of workers [

39]. Many uncritical voices indicate efficiency as the main goal of the company’s operations, barely noticing the social role of the company and the broadly understood interests of employees (including the well-being and life balance of employees). Such a statement is a pretext for them to shape working conditions only to the extent required by law. For example, value management (VBM) is a philosophy of enterprise management, according to which the company’s operations and management processes are focused on maximizing its value from the point of view of the owners’ interests and the capitals involved [

54]. This concept adopts the idealistic and questionable assumption that an increase in the value of an enterprise may be possible when the value for other stakeholder groups grows. It should be remembered that the captured value appropriate by groups of stakeholders depends on their strength. The concept of CSR tries to moderate this approach by incorporating social responsibility into the logic of the corporate strategy [

55]. The importance of employees as stakeholders is underlined by the SA8000 standard [

56]. Many researchers emphasize the work ethos and its importance for the sense of personal worth [

57], other currents view work as an enemy of freedom [

40].

Treating the employee only as a mode of the production process, which is required to be more and more efficient while limiting the resources supporting the work. At the same time, limiting the employees share in the obtained benefits and the broadly understood participation, may lead to discouragement, burnout, and lower self-esteem.

The conducted research shows that the concept of work proposed in the surveyed company clashes with the concept of work–life balance. It is a form of a reduced philosophy of LM, which focuses on reducing all waste (MUDA) and increasing efficiency, omitting, or simulating activities in the area of MURI (overload) and MURA (imbalance).

The research directs us towards an experiment aimed at verifying the hypothesis: whether the working conditions based on the assumption of limiting overloads will have a positive impact on efficiency in the long term. The implementation of such a study may be difficult due to the necessity to interfere with the living organism of the enterprise. Comparing performance across different types of organization can lead to misleading conclusions.

6. Conclusions

The quality of order processing depends most of all on the flawless work of employees. The conducted research confirmed the hypothesis; the research also revealed the problem of the excessive workload of the management and employees. The study showed that improving working conditions can help both by eliminating errors in order processing and by improving the health of employees. As a result of the study, it was found that the most important problems in order picking are: order fulfilment time and collection of damaged products for orders. The observations conducted and Ishikawa’s cause and effect analyzes lead to the conclusion that the significant, but not the only factors shaping the scale of these anomalies are working conditions. This is since most of the identified error causes are related to working conditions, meaning that appropriate shaping of these conditions can reduce the errors that arise. The research conclusions indicate that improving working conditions may have a significant impact on reducing the number of errors in the process. The main issues include:

Work being too strenuous, too high a pace of collection imposed on employees making them disregard the unattainable norms outright, especially less experienced employees; this is reflected in unjustified downtime;

Ten-hour shifts requiring the employees to maintain focus and attention too long;

Noise and temperature changes lowering employee concentration;

Too large of a distance between goods;

No rational solutions for handling damaged goods, forcing the employees to make additional rounds (waste of time);

The low commitment of employees:

- ○

For some employees, the work is only seasonal;

- ○

Employees get insufficient training;

- ○

Low promotion prospects;

- ○

High employee turnover means the employees do not tie their future to the company.

Observed threats to employee health include:

Repetitive, intense work, including the work efficiency parameters that get worse in time (expected number of retrievals per hour per employee);

Teamwork, the pace of work depends on the work of colleagues and machines;

Rotating schedules.

The conducted research shows the following implications for practice:

Rotation of the warehouse product system with seasonal changes in demand, seasonal rule: as close to the picking location as possible (tape, point);

Introduction of automation for heavy and bulky items;

Introduction of an intensity measure in the formula number of orders picked in a specific hour, e.g., three pickings in the 4th working hour (a measure more understandable than the standard deviation or the coefficient of variation) 3//4. Thus, the entry 3//5 means three pickings in the fifth working hour; adjusting work schedules to the employee’s fatigue curve (the need to determine the fatigue curve); keeping hourly records of the time of picking up employees;

Determining the optimal route by the IT system; standardization of packaging;

The lighting of sensitive places;

Damaged products, damaged packaging—apply the principle “goes together”—after identifying the damaged product, it is transported together with the correct one to the picking line/point and put into a separate/distinctive container, then it is transported to the dispatch department along with other correct orders and there, placed in one central place for storing damaged products;

Shortening the shifts to 8 h, reducing the time the employee is exposed to noise and varying temperatures, thus limiting those working hours that cause the most errors (when concentration is lowest);

Stabilizing the retrieval rate at a constant;

Offering more training in retrievals and handling damaged goods;

Offering bonuses for faultless work;

Adjusting the number of the people reporting to a single manager to the standard of management span;

Proposing procedural solutions for damaged goods;

Audits for orders and goods placement, basing the optimal placement of goods on those audits (possibly with seasonal changes), using a variable shelf model.

As previously stated, the research results are not universal and related to the specific circumstances of the company in question. The study was conducted in a company with a wide range of consumer goods with various packaging dimensions (low standardization), with a very high proportion of human labor. In enterprises with higher standardization of packaging, it is easier to automate the order picking process. The test results are preliminary studies leading to the determination of further research steps, this applies to the standard measurement methods used. During the research, it was found that subsequent research should be conducted using more detailed measures. These measures should make it possible to determine the number of downloads in each hour of an employee’s work.

The results of the conducted research encourage further study, especially into the relationship between the number of errors committed and hours worked, as well as reasons for employee absence. The main direction of further research is to deepen the knowledge about the distribution of labor productivity over time, and consequently the verification of traditional performance measures, such as the average measure of the number of orders completed over a specific time or the average picking time. Verification of the cognitive value of these traditional measures should lead to the development and proposition of the use of new measures. Introduction of measures taking into account the effects of employee fatigue/overload, e.g., the time of performance breakdown—calculated as work time followed by performance deterioration, performance variability per unit of time; introducing the average picking time per hour with supplementing this measure with the standard deviation or the coefficient of variation. Conducting a causal analysis of the phenomenon of employee absenteeism. Identification of the variables shaping this value, in particular, employee overload understood as excessive work intensity and working time, the required number of picking and mental demand. In a positive sense, deepening the knowledge of the shape factors contributing to the well-being of employees.