How Do Nature-Based Solutions’ Color Tones Influence People’s Emotional Reaction? An Assessment via Virtual and Augmented Reality in a Participatory Process

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. NBS and the Relevance of Citizens Engagement

2.2. Augmented and Virtual Reality as Citizens’ Engagement Solutions

2.3. Green Effects: Natural Elements and Color Clues

- (1)

- Analysis of the correlations between different color tones and emotions.

- (2)

- Reliability analysis of the detected correlations, comparing the results obtained in AR and VR.

3. Methods

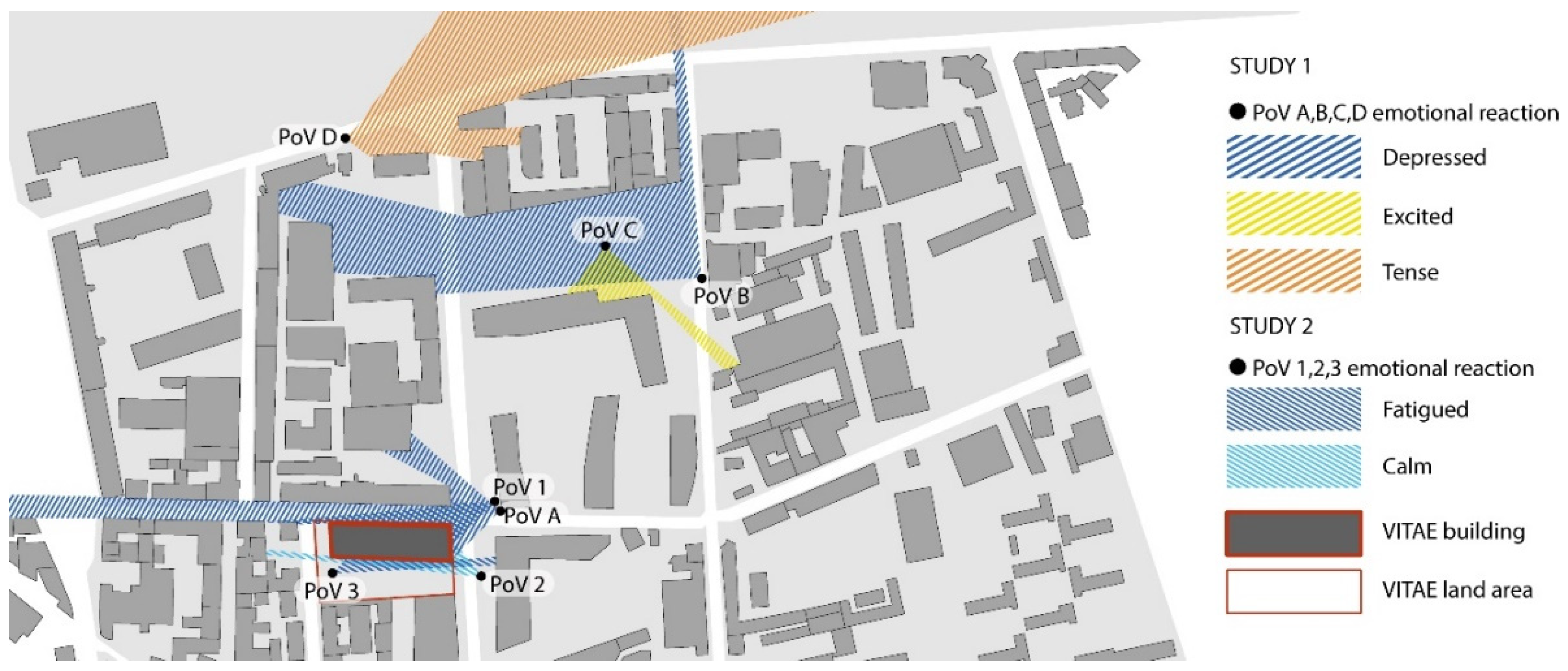

3.1. Materials

3.2. Procedure and Participants

3.3. Analyses

- LIGHTNESS: “The brightness of an area judged relative to the brightness of a similarly illuminated area that appears to be white or highly transmitting” [120] (p. 88), analyzed in the following ways: (1) average brightness of the image; (2) percentage of low-brightness pixels (L < 15%); (3) percentage of high-brightness pixels (L > 85%); (4) average brightness of low-saturation pixels only.

- OPPOSITIVE CHANNELS: “The a* and b* dimensions approximately correlated with red-green and yellow-blue chroma perceptions” [120] (p. 202), analyzed in the following ways: (1) average oppositional a* green-red; (2) average oppositional b* blue-yellow.

- HUE: “Attribute of a visual perception according to which an area appears to be similar to one of the colors—red, yellow, green, and blue—or to a combination of adjacent pairs of these colors considered in a closed ring” [120] (p. 88), calculated in a range [0°:180°], it is analyzed in the following ways: (1) percentage of orange tones pixels (8° ≤ H < 23°); (2) percentage of yellow tones pixels (23° ≤ H < 38°); (3) percentage of lime tones pixels (38° ≤ H < 53°); (4) percentage of green tones pixels (53° ≤ H < 68°); (5) percentage of turquoise tones pixels (68° ≤ H < 83°); (6) percentage of cyan tones pixels (83° ≤ H < 98°); (7) percentage of cobalt tones pixels (98° ≤ H < 113°); (8) percentage of blues tones pixels (113° ≤ H < 143°); (9) percentage of violet tones pixels (128° ≤ H < 143°); (10) percentage of magenta tones pixels (143° ≤ H < 158°); (11) percentage crimson tones pixels (158° ≤ H < 173°); (12) percentage of red tones pixels (173° ≤ H < 179° and 0° ≤ H < 8°).

- SATURATION: “Colorfulness of an area judged in proportion to its brightness” [120] (p. 91), it is calculated for each image as: (1) mean saturation of the entire image; (2) the percentage of the pixels’ area belonging to the same hue, or more simply, the image surface with the same color tones, (3) the ‘mean saturation’ of a specific hue, that is the average saturation of a color’s tone range, and (4) the ‘weighted saturation’, i.e., the combination of the previous two, that is the ratio between the mean saturation and the pixels’ area of a specific hue. Furthermore, each image was filtered on the base of the L channel (CIELAB) to analyze: (i) saturation of low lightness pixels; (ii) saturation of high lightness pixels.

4. Results

4.1. Emotional Reactions to the Simulated Urban Environment

4.2. Color Features and Emotional Reactions

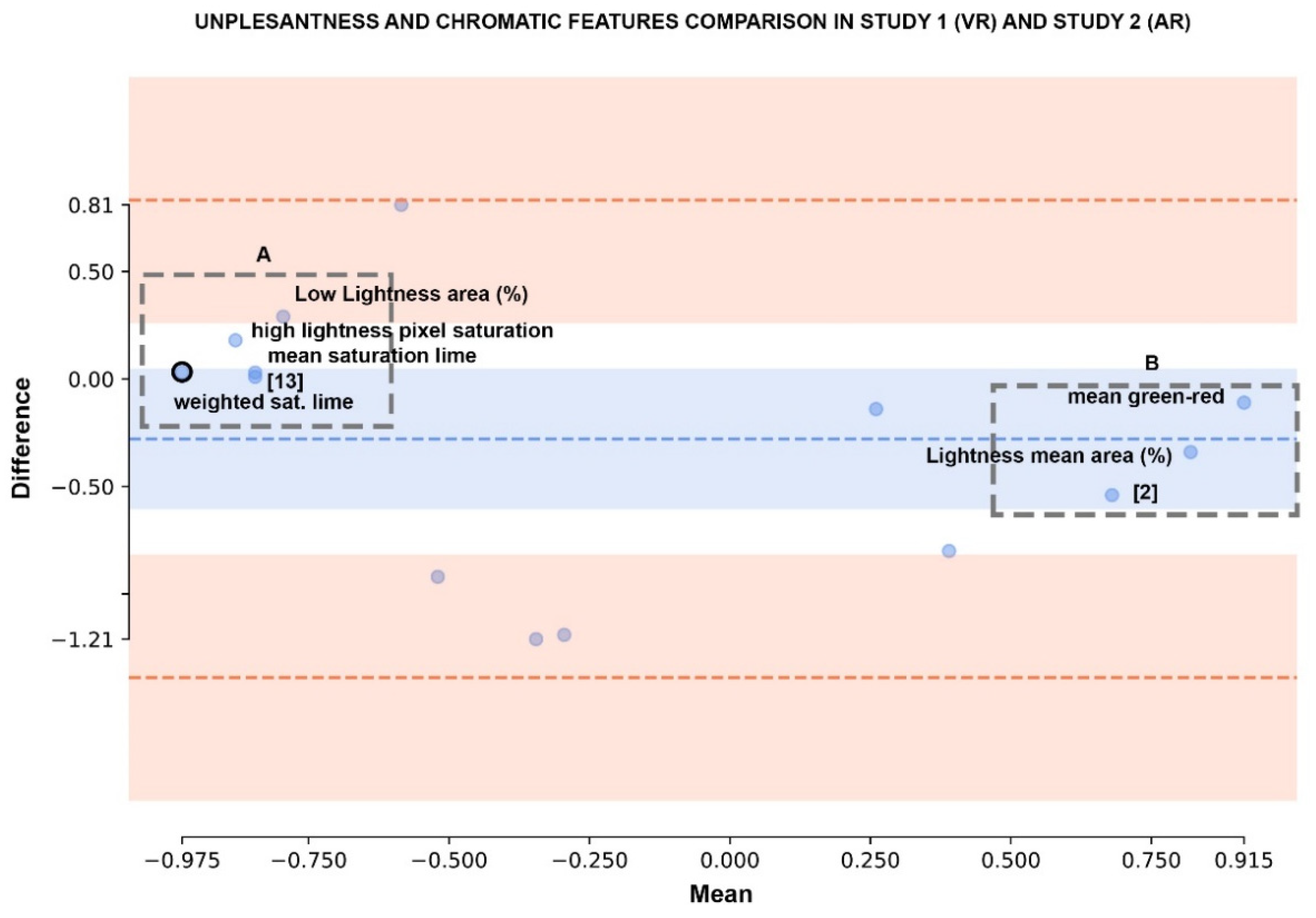

- To show a significant correlation in at least one of the two studies: p < 0.05.

- To be included in the Bland-Altman interval of confidence: Difference in the range [(mean distance from equality—t_confidence) ∶ (mean distance from equality + t_confidence)], where the mean distance from equality is the mean of all difference values related to an emotional parameter.

- To show a high level of agreement in the two studies comparisons: |mean correlation| > 0.75.

4.3. Agreements Cluster Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Towards an EU Research and Innovation Policy Agenda for Nature-Based Solutions & Re-Naturing Cities: Final Report of the Horizon 2020 Expert Group on “Nature Based Solutions and Re Naturing Cities; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2015; ISBN 978-92-79-46048-7. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre, N.; Fritz, M.; Freitas, T.; de Boissezon, B.; Vandewoestijne, S. Nature-Based Solutions in the EU: Innovating with Nature to Address Social, Economic and Environmental Challenges. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenership for Environment and Disaster Risk Reduction; Friends of EbA. Promoting Nature-Based Solutions in the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nesshöver, C.; Assmuth, T.; Irvine, K.N.; Rusch, G.M.; Waylen, K.A.; Delbaere, B.; Haase, D.; Jones-Walters, L.; Keune, H.; Kovacs, E.; et al. The Science, Policy and Practice of Nature-Based Solutions: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, I.D. Environmental Information and Technology: Is It All Too Much? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 47, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Barreira, A.P.; Loures, L.; Antunes, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Stakeholders’ Engagement on Nature-Based Solutions: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rainisio, N.; Boffi, M.; Riva, E. Positive Change in Environment: Aesthetics, Environmental Flowability and Well-Being. In Enabling Positive Change: Flow and Complexity in Daily Experience; Inghilleri, P., Riva, G., Riva, E., Eds.; DE GRUYTER OPEN: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-11-041024-2. [Google Scholar]

- Joye, Y. Architectural Lessons from Environmental Psychology: The Case of Biophilic Architecture. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2007, 11, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kellert, S.R.; Heerwagen, J.H.; Mador, M.L. Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.; Wilson, E. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, F.; Gou, Z.; Lau, S.S.-Y.; Lau, S.-K.; Chung, K.-H.; Zhang, J. From Biophilic Design to Biophilic Urbanism: Stakeholders’ Perspectives. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 211, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Larsen, L.; Deal, B.; Sullivan, W.C. A Dose–Response Curve Describing the Relationship between Tree Cover Density and Landscape Preference. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 139, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; ISBN 978-0-521-34939-0. [Google Scholar]

- White, E.V.; Gatersleben, B. Greenery on Residential Buildings: Does It Affect Preferences and Perceptions of Beauty? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, J.J. Justice in Nature-Based Solutions: Research and Pathways. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 180, 106874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Newman, L.L. Sustainable Development for Some: Green Urban Development and Affordability. Local Environ. 2009, 14, 669–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, S.; Haase, A.; Andersson, E.; Banzhaf, E.; Baró, F.; Brenck, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; et al. Greening Cities—To Be Socially Inclusive? About the Alleged Paradox of Society and Ecology in Cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, W.; Hamilton, T. Just Green Enough: Contesting Environmental Gentrification in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, D.; Li, C.Q.; Wolch, J.; Kahle, C.; Jerrett, M. A Spatial Autocorrelation Approach for Examining the Effects of Urban Greenspace on Residential Property Values. J. Real Estate Finance Econ. 2010, 41, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, R. Impacts of Street-Visible Greenery on Housing Prices: Evidence from a Hedonic Price Model and a Massive Street View Image Dataset in Beijing. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zuniga-Teran, A.A.; Gerlak, A.K. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Analyzing Questions of Justice Issues in Urban Greenspace. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Urban Public Green Spaces Availability: A Localized Modeling Approach to Inform Land Use Policy. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, K.A.; Lewis, T.L. Green Gentrification: Urban Sustainability and the Struggle for Environmental Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-41780-4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Kuzovkina, Y.A.; Weiner, D. Who Lives in Greener Neighborhoods? The Distribution of Street Greenery and Its Association with Residents’ Socioeconomic Conditions in Hartford, Connecticut, USA. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipilä, M.; Tyrväinen, L. Evaluation of Collaborative Urban Forest Planning in Helsinki, Finland. Urban For. Urban Green. 2005, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, I.; Morello, E. Co-Creation Pathway as a Catalyst for Implementing Nature-Based Solution in Urban Regeneration Strategies Learning from CLEVER Cities Framework and Milano as Test-Bed. Urban. Inf. Interruptions Intersect. Shar. Overlapping New Perspect. Territ. 2018, 25, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg, J. Why Not to Green a City? Institutional Barriers to Preserving Urban Ecosystem Services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 12, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.B.; Davison, A.; Daniels, G.D. Sinners, Scapegoats or Fashion Victims? Understanding the Deaths of Trees in the Green City. Geoforum 2013, 48, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki, J.; Sipilä, M. Hopping on One Leg—The Challenge of Ecosystem Disservices for Urban Green Management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009, 8, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, J.B.; Davison, A.; Harwood, A. How Tree Professionals Perceive Trees and Conflicts about Trees in Australia’s Urban Forest. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 119, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffi, M.; Riva, E.; Rainisio, N. Positive Change and Political Participation: Well-Being as an Indicator of the Quality of Citizens’ Engagement. In Enabling Positive Change: Flow and Complexity in Daily Experience; Inghilleri, P., Riva, G., Riva, E., Eds.; DE GRUYTER OPEN: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-11-041024-2. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Cowley, J.; Hollander, J. The New Generation of Public Participation: Internet-Based Participation Tools. Plan. Pract. Res. 2010, 25, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, Ø.; Rose, J.; Flak, L. The Shape of Eparticipation: Characterizing an Emerging Research Area. Gov. Inf. Q. 2008, 25, 400–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Desouza, K.C.; Bhagwatwar, A. Technology-Enabled Participatory Platforms for Civic Engagement: The Case of U.S. Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2014, 21, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picon, A. Smart Cities. A Spatialised Intelligence. AD 2015, 49, 5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffi, M.; Pola, L.; Fumagalli, N.; Fermani, E.; Senes, G.; Inghilleri, P. Nature Experiences of Older People for Active Ageing: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Co-Design of Community Gardens. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, N.; Fermani, E.; Senes, G.; Boffi, M.; Pola, L.; Inghilleri, P. Sustainable Co-Design with Older People: The Case of a Public Restorative Garden in Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanhere, S.S. Participatory Sensing: Crowdsourcing Data from Mobile Smartphones in Urban Spaces. In Proceedings of the ICDCIT 2013, Bhubaneswar, India, 5–7 February 2013; Hota, C., Srimani, P.K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, N. Vulnerability, Risk and Adaptation: A Conceptual Framework; Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research: Norwich, UK, 2003; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bosselmann, P. Urban Transformation: Understanding City Form and Design; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-61091-149-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ertiö, T.-P. Participatory Apps for Urban Planning—Space for Improvement. Plan. Pract. Res. 2015, 30, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, G.; Cirri, A.; Corradi, A.; Foschini, L.; Ianniello, R.; Montanari, R. Crowdsensing in Urban Areas for City-Scale Mass Gathering Management: Geofencing and Activity Recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 2014, 14, 4185–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capineri, C.; Huang, H.; Gartner, G. Tracking Emotions in Urban Space. Two Experiments in Vienna and Siena. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 2018, 125, 273–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson-Smith, A.; Evans, S.; Batty, M. Building the Virtual City: Public Participation through e-Democracy. Knowl. Technol. Policy 2005, 18, 62–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostou, K.; Vlamos, P. Square AR: Using Augmented Reality for Urban Planning. In Proceedings of the 2011 Third International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications, Athens, Greece, 4–6 May 2011; pp. 128–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bosché, F.; Tingdahl, D.; Carozza, L.; Gool, L.V. Markerless Vision-Based Augmented Reality for Enhanced Project Visualization. Gerontechnology 2012, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imottesjo, H.; Kain, J.-H. The Urban CoBuilder—A Mobile Augmented Reality Tool for Crowd-Sourced Simulation of Emergent Urban Development Patterns: Requirements, Prototyping and Assessment. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2018, 71, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Alcaide Muñoz, L. E-Participation in Smart Cities: Technologies and Models of Governance for Citizen Engagement; Public Administration and Information Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 34, ISBN 978-3-319-89473-7. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.-A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for Planning the Development of Smart Cities. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, D. Understanding Professional Media. In Human Behavior and Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 43–88. ISBN 978-1-4684-0810-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bosselmann, P. Representation of Places: Reality and Realism in City Design; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-520-20658-8. [Google Scholar]

- Piga, B.E.A.; Morello, E. Environmental Design Studies on Perception and Simulation: An Urban Design Approach. Int. J. Sens. Environ. Archit. Urban Space 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheppard, S.R.J. Visual Simulation: A User Guide for Architects, Engineers, and Planners; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-442-27827-4. [Google Scholar]

- McKechnie, G.E. Simulation Techniques in Environmental Psychology. In Perspectives on Environment and Behavior; Stokols, D., Ed.; Plenum Press: London, UK, 1977; pp. 169–189, ISBN 13: 978-1-4684-2279-5. [Google Scholar]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Saeidi-Rizi, F.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H.; Pei, Y. The Role of Methodological Choices in the Effects of Experimental Exposure to Simulated Natural Landscapes on Human Health and Cognitive Performance: A Systematic Review. Environ. Behav. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogiuri, G.; Litleskare, S.; Fagerheim, K.A.; Rydgren, T.L.; Brambilla, E.; Thurston, M. Experiencing Nature through Immersive Virtual Environments: Environmental Perceptions, Physical Engagement, and Affective Responses during a Simulated Nature Walk. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahn, P.H.; Severson, R.L.; Ruckert, J.H. The Human Relation With Nature and Technological Nature. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellgren, A.; Buhrkall, H. A Comparison of the Restorative Effect of a Natural Environment with That of a Simulated Natural Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassonde, K.A.; Gloth, C.A.; Borchert, K. Windowless Classrooms or a Virtual Window World: Does a Creative Classroom Environment Help or Hinder Attention? Teach. Psychol. 2012, 39, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J.M.; Blascovich, J.J.; Beall, A.C. Immersive Virtual Environment Technology as a Basic Research Tool in Psychology. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 1999, 31, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dede, C. Immersive Interfaces for Engagement and Learning. Science 2009, 323, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edler, D.; Keil, J.; Wiedenlübbert, T.; Sossna, M.; Kühne, O.; Dickmann, F. Immersive VR Experience of Redeveloped Post-Industrial Sites: The Example of “Zeche Holland” in Bochum-Wattenscheid. KN-J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2019, 69, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loyola, M.; Rossi, B.; Montiel, C.; Daiber, M. Use of Virtual Reality in Participatory Design. In Blucher Design Proceedings; Editora Blucher: Porto, Portugal, 2019; pp. 449–454. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.S.; Angelini, C.; Kress, M.; Ramos Vieira, E.; D’Souza, N.; Rishe, N.D.; Medina, J.; Özer, E.; Ortega, F. Augmented Reality for City Planning. In Proceedings of the Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality. Design and Interaction, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Chen, J.Y.C., Fragomeni, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 256–271. [Google Scholar]

- Saßmannshausen, S.M.; Radtke, J.; Bohn, N.; Hussein, H.; Randall, D.; Pipek, V. Citizen-Centered Design in Urban Planning: How Augmented Reality Can Be Used in Citizen Participation Processes. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021, Virtual Event, USA, 28 June 2021; pp. 250–265. [Google Scholar]

- Nitoslawski, S.A.; Galle, N.J.; Van Den Bosch, C.K.; Steenberg, J.W.N. Smarter Ecosystems for Smarter Cities? A Review of Trends, Technologies, and Turning Points for Smart Urban Forestry. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 51, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, J.P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velarde, M.D.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M. Health Effects of Viewing Landscapes—Landscape Types in Environmental Psychology. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.; Tassinary, L.G.; Ulrich, R.S.; Hebl, M.R.; Grossman-Alexander, M. The View From The Road: Implications for Stress Recovery and Immunization. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tennessen, C.M.; Cimprich, B. Views to Nature: Effects on Attention. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. The Role of Nature in Coping with Psycho-Physiological Stress: A Literature Review on Restorativeness. Behav. Sci. 2014, 4, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richardson, M.; McEwan, K.; Maratos, F.; Sheffield, D. Joy and Calm: How an Evolutionary Functional Model of Affect Regulation Informs Positive Emotions in Nature. Evol. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 2, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijkstra, K.; Pieterse, M.; Pruyn, A. Physical Environmental Stimuli That Turn Healthcare Facilities into Healing Environments through Psychologically Mediated Effects: Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, G.A. Does A View of Nature Promote Relief From Acute Pain? J. Holist. Nurs. 2009, 27, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting With Nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, F.E.; Sullivan, W.C. Aggression and Violence in the Inner City: Effects of Environment via Mental Fatigue. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, W.C.; Kuo, F.E.; Depooter, S.F. The Fruit of Urban Nature: Vital Neighborhood Spaces. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 678–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Evans, G.W. Nearby Nature: A Buffer of Life Stress among Rural Children. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engemann, K.; Svenning, J.-C.; Arge, L.; Brandt, J.; Geels, C.; Mortensen, P.B.; Plana-Ripoll, O.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Pedersen, C.B. Natural Surroundings in Childhood Are Associated with Lower Schizophrenia Rates. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 216, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krabbendam, L.; van Os, J. Schizophrenia and Urbanicity: A Major Environmental Influence—Conditional on Genetic Risk. Schizophr. Bull. 2005, 31, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M. Adolescents’ Favourite Places and Environmental Self-Regulation. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Restorative Experience and Self-Regulation in Favorite Places. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, S.M.; Jeitziner, M.-M.; Wyss, P.; Chesham, A.; Urwyler, P.; Müri, R.M.; Jakob, S.M.; Nef, T. Visuo-Acoustic Stimulation That Helps You to Relax: A Virtual Reality Setup for Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pasca, L.; Carrus, G.; Loureiro, A.; Navarro, Ó.; Panno, A.; Tapia Follen, C.; Aragonés, J.I. Connectedness and Well-Being in Simulated Nature. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, N.L.; White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Garside, R.; Dean, S.G.; Smalley, A.J.; Gatersleben, B. What Is the Best Way of Delivering Virtual Nature for Improving Mood? An Experimental Comparison of High Definition TV, 360° Video, and Computer Generated Virtual Reality. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 72, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felnhofer, A.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Schmidt, M.; Heinzle, A.-K.; Beutl, L.; Hlavacs, H.; Kryspin-Exner, I. Is Virtual Reality Emotionally Arousing? Investigating Five Emotion Inducing Virtual Park Scenarios. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2015, 82, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kort, Y.A.W.; Meijnders, A.L.; Sponselee, A.A.G.; IJsselsteijn, W.A. What’s Wrong with Virtual Trees? Restoring from Stress in a Mediated Environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.P.; Mayer, M.D.; Fellows, A.M.; Cowan, D.R.; Hegel, M.T.; Buckey, J.C. Relaxation with Immersive Natural Scenes Presented Using Virtual Reality. Aerosp. Med. Hum. Perform. 2017, 88, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, L.M.; Sherman, J. Virtual Nature: A Psychologically Beneficial Experience. In Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality. Multimodal Interaction; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Chen, J.Y.C., Fragomeni, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11574, pp. 441–449. ISBN 978-3-030-21606-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chiang, Y. The Influence of Forest Resting Environments on Stress Using Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gao, T.; Zhu, L.; Qiu, L.; Gao, T.; Gao, Y. Exploring Psychophysiological Restoration and Individual Preference in the Different Environments Based on Virtual Reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elliot, A.J.; Maier, M.A. Color Psychology: Effects of Perceiving Color on Psychological Functioning in Humans. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Zhu, R. (Juliet) Blue or Red? Exploring the Effect of Color on Cognitive Task Performances. Science 2009, 323, 1226–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lichtenfeld, S.; Elliot, A.J.; Maier, M.A.; Pekrun, R. Fertile Green: Green Facilitates Creative Performance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akers, A.; Barton, J.; Cossey, R.; Gainsford, P.; Griffin, M.; Micklewright, D. Visual Color Perception in Green Exercise: Positive Effects on Mood and Perceived Exertion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8661–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, T.; Costall, A. The Emotional Connotations of Color: A Qualitative Investigation. Color Res. Appl. 2008, 33, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, A.K.; Robinson, M.D.; Meier, B.P. Anger as “Seeing Red”: Evidence for a Perceptual Association. Cogn. Emot. 2012, 26, 1445–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, R.A.; Barton, R.A. Red Enhances Human Performance in Contests. Nature 2005, 435, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadid, A.; Koplin, M.; Stephan, S.; Hering-Bertram, M.; Paelke, V.; Teschke, T.; Helmut, E. Express Yourself/City—Smart Participation Culture Technologies. In Smart Cities in the Mediterranean. Coping with Sustainability. Objectives in Small and Medium-sized Cities and Island Communities; Stratigea, A., Kyriakides, E., Nicolaides, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, F.M.; Osgood, C.E. A Cross-Cultural Study of the Affective Meanings of Color. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1973, 4, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, P.; Mehrabian, A. Effects of Color on Emotions. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1994, 123, 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, A.; Siret, D.; Simonnot, N. Capturing Chromatic Effects in Urban Environment. In Experiential Walks for Urban Design: Revealing, Representing, and Activating the Sensory Environment; Piga, B.E.A., Siret, D., Thibaud, J.-P., Eds.; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 207–222. ISBN 978-3-030-76694-8. [Google Scholar]

- Manav, B. Color-Emotion Associations, Designing Color Schemes for Urban Environment-Architectural Settings. Color Res. Appl. 2017, 42, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.E.; Schloss, K.B. An Ecological Valence Theory of Human Color Preference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8877–8882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armondi, S.; Bruzzese, A. Contemporary Production and Urban Change: The Case of Milan. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, J.; Mahmoud, I. Urban Design and the Role of Placemaking in Mainstreaming Nature-Based Solutions. Learning From the Biblioteca Degli Alberi Case Study in Milan. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.J.A.; Butalid, L.; Penke, L.; van Aken, M.A.G. The Effects of Weather on Daily Mood: A Multilevel Approach. Emotion 2008, 8, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Höppe, P. Different Aspects of Assessing Indoor and Outdoor Thermal Comfort. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendritzky, G.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G. UTCI—Why Another Thermal Index? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.; Deering, D.; Schell, J.; Harlan, J. Monitoring the Vernal Advancement and Retrogradation (Green Wave Effect) of Natural Vegetation; ScienceOpen, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Pratt, G. A Description of the Affective Quality Attributed to Environments. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 38, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedikt, M.L. To Take Hold of Space: Isovists and Isovist Fields. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1979, 6, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morariu, V.I.; Prasad, V.S.N.; Davis, L.S. Human Activity Understanding Using Visibility Context. IEEERSJ IROS Workshop Sens. Hum. Spat. Concepts FS2HSC 2007, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Birant, D.; Kut, A. ST-DBSCAN: An Algorithm for Clustering Spatial–Temporal Data. Data Knowl. Eng. 2007, 60, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.D.; Jiang, X.H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J. Color Image Segmentation: Advances and Prospects. Pattern Recognit. 2001, 34, 2259–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, M.D. Color Appearance Models. In The Wiley-IS&T Series in Imaging Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-65309-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce, C. Correlation, Agreement, and Bland–Altman Analysis: Statistical Analysis of Method Comparison Studies. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 148, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavarina, D. Understanding Bland Altman Analysis. Biochem. Medica 2015, 25, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elsadek, M.; Sayaka, S.; Fujii, E.; Koriesh, E.; Moghazy, E.; Fatah, Y.A.E. Human Emotional and Psycho-Physiological Responses to Plant Color Stimuli. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2013, 11, 1584–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Elsadek, M.; Sun, M.; Fujii, E. Psycho-Physiological Responses to Plant Variegation as Measured through Eye Movement, Self-Reported Emotion and Cerebral Activity. Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hedo, R.; Rivera, A.; Rull, R.; Richardson, S.; Tu, X.M. Post Hoc Power Analysis: Is It an Informative and Meaningful Analysis? Gen. Psychiatry 2019, 32, e100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feldman Barrett, L.; Russell, J.A. Independence and Bipolarity in the Structure of Current Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 967–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Theory of Affordances. In Perceiving, Acting and Knowing; Shaw, R., Bransford, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; distributed by the Halsted Press Division; Wiley: Hillsdale, NJ, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1977; ISBN 978-0-470-99014-8. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The Emotional Affordances of Forest Settings: An Investigation in Boys with Extreme Behavioural Problems. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.-T.; Ruan, L.-W. Effects of Indoor Plants on Self-Reported Perceptions: A Systemic Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bringslimark, T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G. The Psychological Benefits of Indoor Plants: A Critical Review of the Experimental Literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffi, M.; Rainisio, N. To Be There, or Not to Be. Designing Subjective Urban Experiences. In Urban Design and Representation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Piga, B.E.A. The Combined Use of Environmental and Experiential Simulations to Design and Evaluate Urban Transformations. In Quality of Life in Urban Landscapes; Cocci Grifoni, R., D’Onofrio, R., Sargolini, M., Eds.; The Urban Book Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 357–364. ISBN 978-3-319-65580-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, S.R.J. Guidance for Crystal Ball Gazers: Developing a Code of Ethics for Landscape Visualization. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.R.J. Validity, Reliability and Ethics in Visualization. In Visualization in Landscape and Environmental Planning; Bishop, I.D., Lange, E., Eds.; Routledge—Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]

- Boffi, M.; Rainisio, N.; Riva, E.; Inghilleri, P. Social Psychology of Flow: A Situated Framework for Optimal Experience. In Flow Experience. Empirical Research and Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Image Features | Unpleasant | Pleasant | Sleepiness | Arousal | Unpleasant/Pleasant Continuum | Deactivation/Activation Continuum | Bland-Altman Chart Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (VR) | |||||||

| CIELAB color space | |||||||

| Low Lightness area (%) | −0.65 | 0.11 | −0.55 | −0.21 | −0.32 | −0.37 | [1] |

| High Lightness area (%) | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.52 | [2] |

| Lightness mean (entire pic) | 0.65 | −0.06 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.39 | [3] |

| Mean lightness of neutral hues areas | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.18 | [4] |

| Mean green-red | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.69 | [5] |

| HSV color space | |||||||

| Mean saturation area (%) | −0.18 | 0.62 | −0.02 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.19 | [6] |

| Low light pixel saturation | −0.01 | −0.74 | −0.16 | −0.51 | −0.41 | −0.36 | [7] |

| High light pixel saturation | −0.79 | −0.05 | −0.68 | −0.37 | −0.49 | −0.52 | [8] |

| LIME (HSV) | |||||||

| Lime pixel area (%) | −0.98 | −0.45 | −0.87 | −0.71 | −0.83 | −0.80 | [9] |

| Mean saturation lime | −0.84 | −0.15 | −0.62 | −0.44 | −0.62 | −0.54 | [10] |

| Weighted saturation lime | −0.96 | −0.36 | −0.84 | −0.65 | −0.77 | −0.75 | [11] |

| GREEN (HSV) | |||||||

| Green pixel area (%) | −0.89 | −0.36 | −0.70 | −0.59 | −0.75 | −0.67 | [12] |

| Mean saturation green | −0.83 | −0.07 | −0.68 | −0.39 | −0.54 | −0.53 | [13] |

| Weighted saturation green | −0.95 | −0.33 | −0.81 | −0.61 | −0.75 | −0.72 | [14] |

| Study 2 (AR) | |||||||

| CIELAB color space | |||||||

| Low Lightness area (%) | −0.94 | 0.34 | 0.45 | −0.80 | −0.77 | −0.04 | [1] |

| High Lightness area (%) | 0.95 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.99 | 0.64 | [2] |

| Lightness mean (entire pic) | 0.99 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.47 | 0.97 | 0.46 | [3] |

| Mean lightness of neutral hues areas | 0.33 | 0.94 | 0.90 | −0.61 | 0.62 | 0.99 | [4] |

| Mean green-red | 0.97 | −0.24 | −0.35 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.15 | [5] |

| HSV color space | |||||||

| Mean saturation area (%) | −0.99 | 0.11 | 0.22 | −0.64 | −0.90 | −0.28 | [6] |

| Low light pixel saturation | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.52 | −0.08 | 0.95 | 0.87 | [7] |

| High light pixel saturation | −0.97 | 0.27 | 0.37 | −0.75 | −0.82 | −0.12 | [8] |

| LIME (HSV) | |||||||

| Lime pixel area (%) | −0.06 | −0.99 | −0.98 | 0.80 | −0.39 | −0.95 | [9] |

| Mean saturation lime | −0.85 | 0.53 | 0.62 | −0.91 | −0.62 | 0.17 | [10] |

| Weighted saturation lime | −0.99 | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.46 | −0.97 | −0.47 | [11] |

| GREEN (HSV) | |||||||

| Green pixel area (%) | 0.30 | −0.96 | −0.98 | 0.96 | −0.04 | −0.77 | [12] |

| Mean saturation green | −0.86 | 0.52 | 0.61 | −0.90 | −0.63 | 0.16 | [13] |

| Weighted saturation green | 0.26 | −0.97 | −0.99 | 0.95 | −0.08 | −0.80 | [14] |

| Difference (Study 1–Study 2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Features | Unpleasant | Pleasant | Sleepiness | Arousal | Unpleasant/Pleasant Continuum | Deactivation/Activation Continuum |

| CIELAB color space | ||||||

| Low Lightness area (%) | 0.29 | −0.23 | −1.00 | 0.59 | 0.45 | −0.33 |

| High Lightness area (%) | −0.54 | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.18 | −0.63 | −0.12 |

| Mean Lightness area (%) | −0.34 | −0.15 | 0.60 | −0.23 | −0.65 | −0.07 |

| Mean lightness of neutral hues areas | −0.14 | −0.98 | −0.57 | 0.70 | −0.60 | −0.81 |

| Mean green-red | −0.11 | 0.70 | 1.03 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.54 |

| HSV color space | ||||||

| Mean saturation area (%) | 0.81 | 0.51 | −0.24 | 0.99 | 1.13 | 0.47 |

| Low light pixel saturation | −0.80 | −1.35 | −0.68 | −0.43 | −1.36 | −1.23 |

| High light pixel saturation | 0.18 | −0.32 | −1.05 | 0.38 | 0.33 | −0.40 |

| LIME (HSV) | ||||||

| Lime pixel area (%) | −0.92 | 0.54 | 0.11 | −1.51 | −0.44 | 0.15 |

| Mean saturation lime | 0.01 | −0.68 | −1.24 | 0.47 | 0.00 | −0.71 |

| Weighted saturation lime | 0.03 | −0.26 | −0.85 | −0.19 | 0.20 | −0.28 |

| GREEN (HSV) | ||||||

| Green pixel area (%) | −1.19 | 0.60 | 0.28 | −1.55 | −0.71 | 0.10 |

| Mean saturation green | 0.03 | −0.59 | −1.29 | 0.51 | 0.09 | −0.69 |

| Weighted saturation green | −1.21 | 0.64 | 0.18 | −1.56 | −0.67 | 0.08 |

| Standard deviation | 0.59 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.50 |

| Mean (distance from equality) | −0.28 | −0.11 | −0.31 | −0.12 | −0.21 | −0.24 |

| Standard error | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| Confidence | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.29 |

| Confidence—lower limit mean | −0.62 | −0.48 | −0.74 | −0.62 | −0.57 | −0.53 |

| Confidence—upper limit mean | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Mean [(Study 1 + Study 2)/2] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Features | Unpleasant | Pleasant | Sleepiness | Arousal | Unpleasant/Pleasant Continuum | Deactivation/Activation Continuum |

| CIELAB color space | ||||||

| Low Lightness area (%) | −0.80 | 0.23 | −0.05 | −0.51 | −0.55 | −0.21 |

| High Lightness area (%) | 0.68 | 0.33 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.68 | 0.58 |

| Mean Lightness area (%) | 0.82 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| Mean lightness of neutral hues areas | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.62 | −0.26 | 0.32 | 0.59 |

| Mean green-red | 0.92 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.42 |

| HSV color space | ||||||

| Mean saturation area (%) | −0.59 | 0.37 | 0.10 | −0.15 | −0.34 | −0.05 |

| Low light pixel saturation | 0.39 | −0.07 | 0.18 | −0.30 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| High light pixel saturation | −0.88 | 0.11 | −0.16 | −0.56 | −0.66 | −0.32 |

| LIME (HSV) | ||||||

| Lime pixel area (%) | −0.52 | −0.72 | −0.93 | 0.05 | −0.61 | −0.88 |

| Mean saturation lime | −0.85 | 0.19 | 0.00 | −0.68 | −0.62 | −0.19 |

| Weighted saturation lime | −0.98 | −0.23 | −0.42 | −0.56 | −0.87 | −0.61 |

| GREEN (HSV) | ||||||

| Green pixel area (%) | −0.30 | −0.66 | −0.84 | 0.19 | −0.40 | −0.72 |

| Mean saturation green | −0.85 | 0.23 | −0.04 | −0.65 | −0.59 | −0.19 |

| Weighted saturation green | −0.35 | −0.65 | −0.90 | 0.17 | −0.42 | −0.76 |

| Study 1 and Study 2 Correlations within the Mean Confidence Interval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Features | Unpleasant | Pleasant | Sleepiness | Arousal | Unpleasant/Pleasant Continuum | Deactivation/Activation Continuum |

| CIELAB color space | ||||||

| Low Lightness area (%) | OUT | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT | IN |

| High Lightness area (%) | IN | IN | OUT | IN | OUT | IN |

| Mean Lightness area (%) | IN | IN | OUT | IN | OUT | IN |

| Mean lightness of neutral hues areas | IN | OUT | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT |

| Mean green-red | IN | IN | OUT | IN | IN | OUT |

| HSV color space | ||||||

| Mean saturation area (%) | OUT | IN | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT |

| Low light pixel saturation | OUT | OUT | IN | IN | OUT | OUT |

| High light pixel saturation | OUT | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT | IN |

| LIME (HSV) | ||||||

| Lime pixel area (%) | OUT | IN | IN | OUT | IN | OUT |

| Mean saturation lime | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT | IN | OUT |

| Weighted saturation lime | IN | IN | OUT | IN | OUT | IN |

| GREEN (HSV) | ||||||

| Green pixel area (%) | OUT | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT | OUT |

| Mean saturation green | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT | IN | OUT |

| Weighted saturation green | OUT | IN | OUT | OUT | OUT | OUT |

| Level of Agreement Between Study 1 (VR) And Study 2 (AR) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Features | Unpleasant | Pleasant | Sleepiness | Arousal | Unpleasant/Pleasant Continuum | Deactivation/Activation Continuum |

| CIELAB color space | ||||||

| Low Lightness area (%) | MED. | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| High Lightness area (%) | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Mean Lightness area (%) | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Mean lightness of neutral hues areas | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Mean green-red | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | LOW |

| HSV color space | ||||||

| Mean saturation area (%) | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Low light pixel saturation | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| High light pixel saturation | MED. | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| LIME (HSV) | ||||||

| Lime pixel area (%) | LOW | LOW | HIGH | LOW | LOW | MED. |

| Mean saturation lime | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Weighted saturation lime | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | MED. | LOW |

| GREEN (HSV) | ||||||

| Green pixel area (%) | LOW | LOW | MED. | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Mean saturation green | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

| Weighted saturation green | LOW | LOW | MED. | LOW | LOW | MED. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piga, B.E.A.; Stancato, G.; Rainisio, N.; Boffi, M. How Do Nature-Based Solutions’ Color Tones Influence People’s Emotional Reaction? An Assessment via Virtual and Augmented Reality in a Participatory Process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13388. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313388

Piga BEA, Stancato G, Rainisio N, Boffi M. How Do Nature-Based Solutions’ Color Tones Influence People’s Emotional Reaction? An Assessment via Virtual and Augmented Reality in a Participatory Process. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13388. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313388

Chicago/Turabian StylePiga, Barbara Ester Adele, Gabriele Stancato, Nicola Rainisio, and Marco Boffi. 2021. "How Do Nature-Based Solutions’ Color Tones Influence People’s Emotional Reaction? An Assessment via Virtual and Augmented Reality in a Participatory Process" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13388. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313388

APA StylePiga, B. E. A., Stancato, G., Rainisio, N., & Boffi, M. (2021). How Do Nature-Based Solutions’ Color Tones Influence People’s Emotional Reaction? An Assessment via Virtual and Augmented Reality in a Participatory Process. Sustainability, 13(23), 13388. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313388