Abstract

Urban retail systems in Poland have been changing constantly during the last 30 years. When it seemed that the consumption lifestyle of Poles became stable, and likewise the relations within the urban retail system, it was placed under the strain of the shock of the pandemic. The aim of the study is to discuss challenges that the urban retail systems face as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, how the relationships within those systems have changed and how the resilience of entities that create urban retail systems has changed. The article focuses on the case study of Poland, the largest and the fastest growing country in Central and Eastern Europe. To achieve the research goal, a broad and detailed critical literature review was used: literature, scientific articles, reports and daily press with a business profile were analyzed. Complementary to a qualitative approach was an analysis of quantitative data from the Central Statistical Office of Poland and Eurostat regarding the period from 2007 to 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes a unique occasion in which to conduct a stress-test of the concept of retail resilience in the lively organism of a city; it also delivers a useful framework for analyzing processes occurring in the Polish retail trade. The undertaken research contributes to these concepts by indicating how the shock of COVID-19 could affect components of the urban retail system in ambivalent ways as they express different levels of resilience. Some elements of the system had no problems with adjustments to the shock of the pandemic, whereas others with more rigid structures had problems with adaptation.

1. Introduction

City centers take part in eternal cycle of crises and renewals. They are required to reinvent themselves as some shopping concepts lose their attractiveness and have to be radically modernized. The COVID-19 phenomenon is not unique in this sense. The pandemic that disseminated around the whole world embraced all the sectors of the economy, with retail trade foremost [1], undermining present shopping concepts. Though the COVID-19 hasn’t been a trigger for these changes. The symptoms of the city center crisis were already visible before the pandemic.

The crisis in city centers dates back to the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, an inflow of global capital to retail trade had shaken the old shopping concepts, accelerating the process of their obsolescence by funding new ideas for merchandizing based on competitiveness and convenience. This “retail revolution” decreased the significance, vitality and viability of town centers. As a result, the spatial organization of urban retail system was transformed, as shopping areas moved towards residential areas. The position of the city centers as traditional shopping areas has been systematically undermined in the last decade by online shopping [2]. In this context, COVID-19 has amplified these negative tendencies.

Poland, as the largest and in recent years the fastest growing country in Central and Eastern Europe, constitutes a very interesting place for the observation of changes to city centers. The Polish retail sector experienced an accelerated evolution when it started its transformation to a free market economy in 1989 [3]. As the stages of the evolution of shopping concepts were relatively short due to the catching up process, urban tissue seemed not to be so resilient as in Western Europe, where development took longer and was based on more solid foundations. In Poland, the policy choice of shock transformation as a model of change [4] granted, on the one hand, great opportunities for the flourishing of entrepreneurship, but, on the other, did not offer opportunities for the attainment of capital. For this reason, the retail trade system has been shaped to a great extent by the inflow of foreign capital. Foreign investors quickly started to open super- and hyper-markets [5,6,7,8]. Shopping malls turned out to be particularly important in revolutionizing the urban retail system in Poland. The first facilities of this type appeared in the largest Polish cities in the early 1990s, but the expansion of shopping malls in Poland started at the end of the 1990s [9]. Initially, they were located on the outskirts of cities or in residential areas, while in later years they began to be located more and more often in city centers, representing a source of huge competition for high streets, and also starting a discussion about the crisis of downtown areas in Poland [8,10,11,12].

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a particularly negative impact on the trade, leisure and entertainment sectors, and has also changed the behavior of city dwellers [13,14,15]. To deal with the problem of the rapid spread of COVID-19, countries started to introduce many restrictions on social life and business, such as bans on large events; closure of kindergartens, schools and universities; travel restrictions and even temporary shutdowns of the economy (so-called lockdowns) [13,16,17]. Shopping malls, as well as the entertainment and catering services sectors [15,18,19], were particularly affected. The situation was not improved by falling consumer mood, uncertainty, fear of unemployment and worries about future economic and health situations [13,17,20]. Shops, especially the large ones, such as shopping malls, began to be avoided by customers, and the time spent there was shortened to a necessary minimum [21]. Due to the indicated limitations and concerns in meeting the daily needs of urban residents, the importance of e-commerce [13,22,23,24,25,26] and shops located in residential areas [27,28] began to grow. These new economic conditions and new customer needs and concerns enforced significant changes of relationships within the urban retail systems.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic is not the first in human history. and is unlikely to be the last. In the 20th and 21st centuries, the world faced “Spanish Flu” (1918–1919), the “Asian Flu” (1957–1958), the “Hong Kong Flu” (1968), SARS-CoV-1 (2002–2003) and the “Swine Flu” (2009–2010) [13,29,30]. Hence, the analysis of the course of the pandemic and its socio-economic consequences is very important, so as to prepare for future potential pandemics or other global crises.

2. Materials and Methods

The aim of this study is to discuss challenges that urban retail systems face as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, how the relationships within these systems have changed and the resilience of such systems’ components. The paper focuses on the case study of Poland. The Polish urban retail system has been subject to rapid socio-economic changes in the last 30 years due to the transformation model of shock therapy [4] chosen by the Polish political elites. Thus, this makes it an interesting case, as it is quite puzzling how urban retail system in Poland, which was already adapted to shocks and changes, coped with the unique experience of the global pandemic. The time range covered by the study is from February 2020 to September 2021.

A broad and detailed critical literature review was used to analyze the collected materials. The qualitative sources can be divided into four groups:

- Scientific articles delivering theoretical frameworks concerning the concepts of resilience and sustainability and recent works related to retailing in its various aspects, published in international journals

- Socio-economic and industry reports (e.g., those of the Central Statistical Office of Poland, the Polish Economic Institute, Colliers International, the Retail Institute, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, Deloitte, the McKinsey Company) concerning changes in retail structure and consumption patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic

- The Polish daily press with a business profile (articles published between February 2020–August 2021 in such online magazines as: dziennik.pl, forsal.pl, Business Insider, prawo.pl, Wiadomości Handlowe) concerning the situation of retail companies related to the COVID-19 pandemic

- An historical approach to the literature was also used to briefly describe the background of the creation and transition of urban retail systems in Poland during the last 30 years.

Complementary to a qualitative approach was the analysis of quantitative data regarding the period from 2007 to 2021, obtained from the Central Statistical Office of Poland and Eurostat. A particularly innovative source of quantitative data was the Polish Economic Institute. It established cooperation with global credit card companies to collect data concerning the value of payment transactions [22]. In this way, it was possible to solve the problem of a delay in acquiring adequate data concerning current social and economic situation [31]. Thanks to this, it became possible to visualize the changes in the shopping cart during the pandemic and the effects of inflation in the cost of goods and services. The advantage of the data collected in cooperation with this company over the traditionally collected data of the Central Statistical Office was their high frequency and seasonality [22].

An analysis of changes within the urban retail system in Poland in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted with the support of resilience concepts, ensuring strong a theoretical framework for empirical research. Among many approaches to resilience understood as an adaptation of systems to a shock [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], the concept of the adaptive cycle of retail centers formulated by Celińska-Janowicz and Dolega fits the best [49]. The uniqueness of this concept is that it links town centers’ resilience to its position within the adaptive cycle and associates adaptive capacity with different dimensions of town center performance.

The article consists of seven parts. After the introduction and the methodological part, in the third part the concept of resilience and its relation to sustainability frameworks is described. Following that, the historical background of the creation and transition of urban retail systems in Poland is presented, explaining its specificity and usefulness. The empirical research on the changes in urban retail systems in Poland and the consumption patterns of citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic are analyzed in the fifth and sixth parts. In the conclusions and discussion part, the assessment of the resilience of particular entities creating urban retail systems in Poland is conducted. On the basis of the author’s 15 years’ experience of research of the Polish retail trade, the unique adaptive cycle of urban retail systems in Poland is proposed. The assessments are justified by some references to the literature on the subject; some statements, however, do not have direct references. These assessments can be debatable, as there is a lack of direct data justifying the classification of the components of resilience of the urban retail system in Poland, which could be treated as a limitation, but at the same time could be seen as a starting point for further in-depth research and scientific discussion. Another limitation of this study relates to the discontinuity of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is still an enduring phenomenon to which the retail sector of Poland is trying to adapt. Thus, the data even from the first quarter of 2021 do not display all the dimensions of the pandemic, as its nature and scope is still changing. Moreover, the number of scientific publications analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on the retail sector is still limited, and the data are retrieved with significant delay. When the data for a previous wave of COVID-19 become accessible, already a new wave arrives with some new phenomena and new consequences. However, COVID-19 seems to be such an important shock for the retail sector that it is important to examine it, and to look for the methods of drawing some more up to date conclusions despite the indicated limitations. For this reason, industry reports and the daily press are an important source of knowledge about socio-economic changes during the pandemic. It is important to be aware of some disadvantages of such resources. These reports are often imprecise, very general in their estimations and are without proper descriptions of their measurement methodology. Some industrial reports are also strongly biased, trying to convince their reader of theses that are beneficial for their sponsors.

3. Conceptual Framework

The resilience conceptual framework could be a useful tool to analyze how cities and regions deal with shocks, disturbances and changes. There are three main approaches to this concept [32]. The first one was adapted from physics to ecology, and puts its attention towards the state of balance to which systems return after having recovered from a shock. This approach is used mainly in physical sciences and is called “engineering resilience” [33]. Later, a dynamic approach to resilience was introduced, namely, so-called “ecological resilience”. This kind of resilience was defined as the ability of a system to absorb changes and disturbances without changing its structure. Resilience could be measured either by the speed of returning to the equilibrium (old or new) or by the intensity of the shock it could absorb [34]. Resilience understood in such a way is used in the social sciences in the contexts of resource management, natural disasters and economic crises [32]. The last approach is adaptive resilience. This concept is based on complex systems theory, stressing the ability of a system to anticipate or recognize shocks and to adapt to them. This type of resilience is close to the evolutionary approach in regional economy, geography and other social sciences. In this approach, resilience is an evolutionary and dynamic process of continuous adjustment to complex and unpredictable conditions [32,35,36,37,49]. Adaptive resilience can be defined as “anticipatory or reactive reorganization of the form and function of the system so as to minimize the impact of a destabilizing shock” [38] or as the ability of different types of retail entities to adapt to changes, shocks or crises that challenge the system’s equilibrium without making it unable to perform its functions in a sustainable way [50].

3.1. Retail Resilience

Although the analysis of the resilience of cities and regions has been present in economic sciences since the 1970s, the concept of retail resilience is new. The first considerations on this topic appeared with the Global Financial Crisis. This was a period of decline in consumption, and thus a significant downturn in retail and services. The first research concerning the resilience of city centers, high streets and retail was published in 2011 by Wrigley and Dolega [38]. They used the adaptive resilience concept [37] to analyse the influence of the Global Financial Crisis on retail sector. The conceptual framework of retail resilience was used to explain changes in urban retail systems, and three years later a series of articles on this issue appeared in the Cities journal [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Some of the articles paid attention to the resilience of city centers, downtown areas and the role that shopping malls were playing in the process of change [44,45]. Others referred directly to the dependencies between urban planning and retail resilience [39,41,43]. Single articles on retail resilience appeared regularly in the following years. A paper of Dolega and Celińska-Janowicz [49] has to be mentioned. The authors adapted the concept of adaptive resilience to the contexts of retail and town center dynamics, and on the basis of the adaptive cycle framework [37] they consider how retail sectors and town centers can adapt to changes. In the following years, the topic of retail resilience did not receive much attention, which changed with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many articles concerning this issue were published in 2020–21 [32,46,47,48]. These were articles concerning the concept of resilience at a theoretical level [19], as well as analyses concerning particular cities and countries: Lisbon [32], Würzburg [48] and Scotland [47]. Most of those articles analyze retail resilience in the context of urban policy and its sustainability. The special issue of the Sustainability Journal planned to be published in 2021, concerning the interconnections between resilience and sustainability, is a reminder that the concept of resilience is current and useful when explaining the processes of change in contemporary word [51].

3.2. Between Sustainability and Resilience

Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems especially appropriate to discuss the relationship between retail, consumption and cities in light of two interpretative keys: resilience and sustainability [18]. Sustainability can be analyzed in three dimensions: natural environment, social and economic conditions and their interfaces such as viability, equity and livability [32]. Urban sustainability is often associated with keeping balanced retail systems in various facilities and shopping environments [52,53,54]. It is important that the retail system respond efficiently to the needs and desires of diverse groups of consumers.

The concepts of sustainability and resilience have some similarities as well as some differences. Sustainable development also embodies a wide range of goals concerning resilient growth. However, while resilience is important it is not the only element of sustainability [55,56,57,58]. Both concepts are multidimensional, as they take into consideration social, economic and environmental conditions. Further, sustainability and resilience are multiscale as they can be used in analyses of particular units (e.g., companies), neighborhoods, cities, regions and even on a global scale with different aims and focuses [32]. However, some crucial differences between the two concepts have to be pointed out. Those differences are associated to temporal aspects and to threats and crises involved. Resilience is seen as focused on problem-solving and oriented towards the short-term, and because of that it is often associated with civil defense or management. Most authors analyzing the resilience concept refer to the adaptation capacity of a system to keep working through designing a new path or following the old one. On the other hand, sustainability is associated with planning [59], considered as a normative concept that creates visions of a desirable future, implies transformations and sets goals to be achieved in a particular period of time. Sustainability is analyzed in the context of long-term strategies. Additionally, resilience requires a strategy to achieve the long-term adaptation effect [32].

3.3. Urban Retail System

Urban retail systems [25,32,47] can be analyzed as dynamic and complex economic systems that evolve in a continuous way and adapt themselves to competitive, market and technological challenges and pressures [32,49]. Because of this, the concept of urban retail system resilience is based on the adaptive resilience perspective.

The resilience of retail urban systems is defined as “the ability of stores and shopping areas to tolerate and adapt to changing environments that challenge the retail system’s equilibrium, without causing it to fail to perform its functions in a sustainable way” [42]. The term equilibrium describes a situation in which a network of shopping districts and retail and service entities are provided with the properties that guarantee their economic viability and vitality as well as an efficient response to the needs of different groups of consumers, for example, those who are not mobile at all, and as a result are dependent on local stores [42].

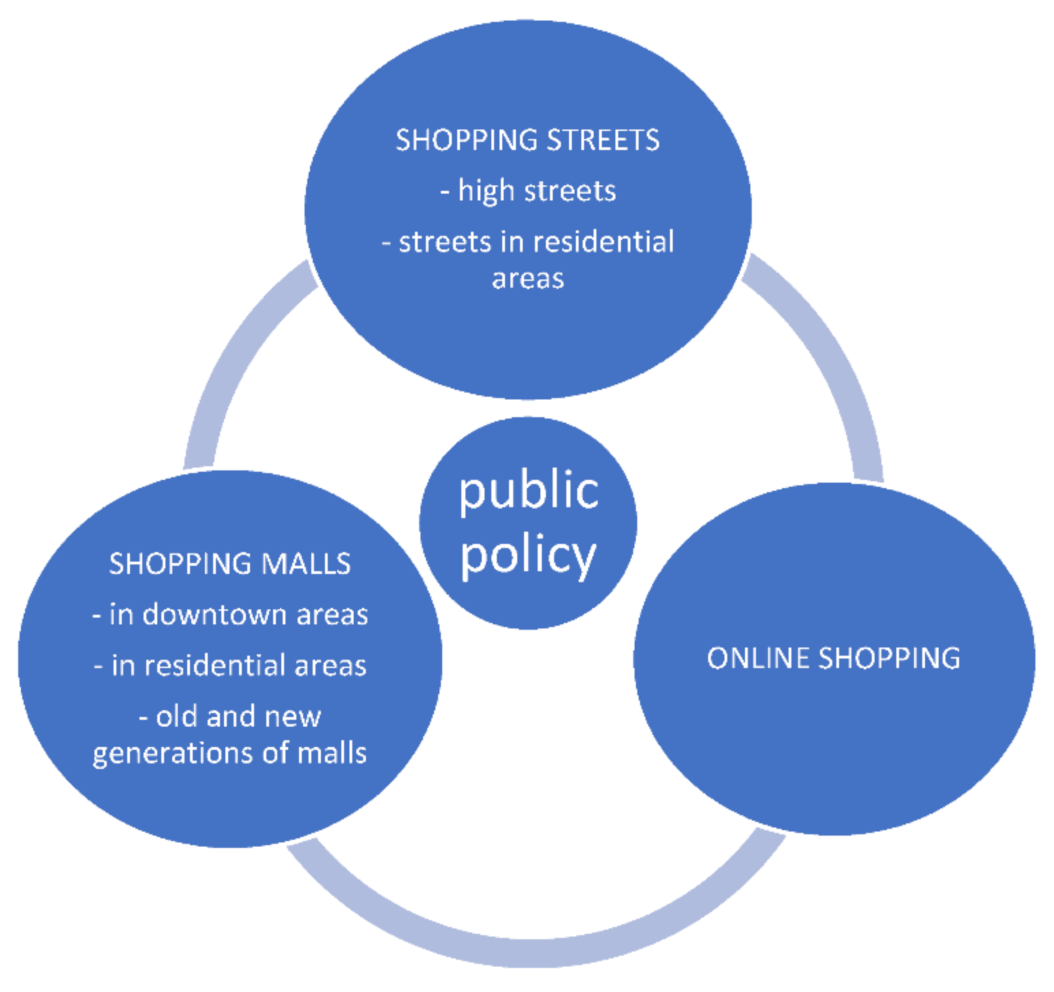

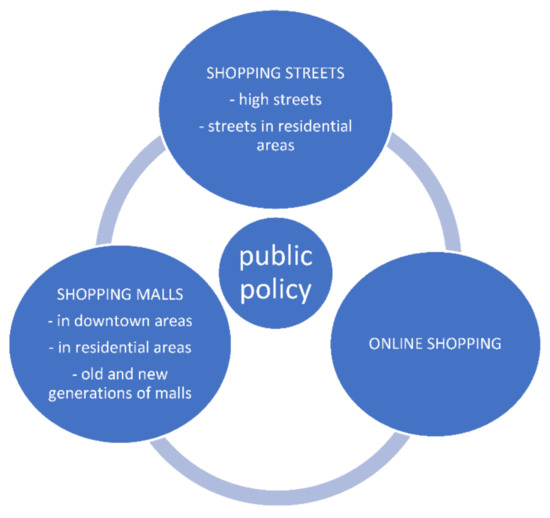

When analyzing urban retail systems in this article, the following three types of entities will be taken into consideration: shopping streets, malls and e-commerce and their mutual interdependences (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Urban retail systems—selected entities. Source: own study (2021).

3.4. Adaptive Cycle of Urban Retail System

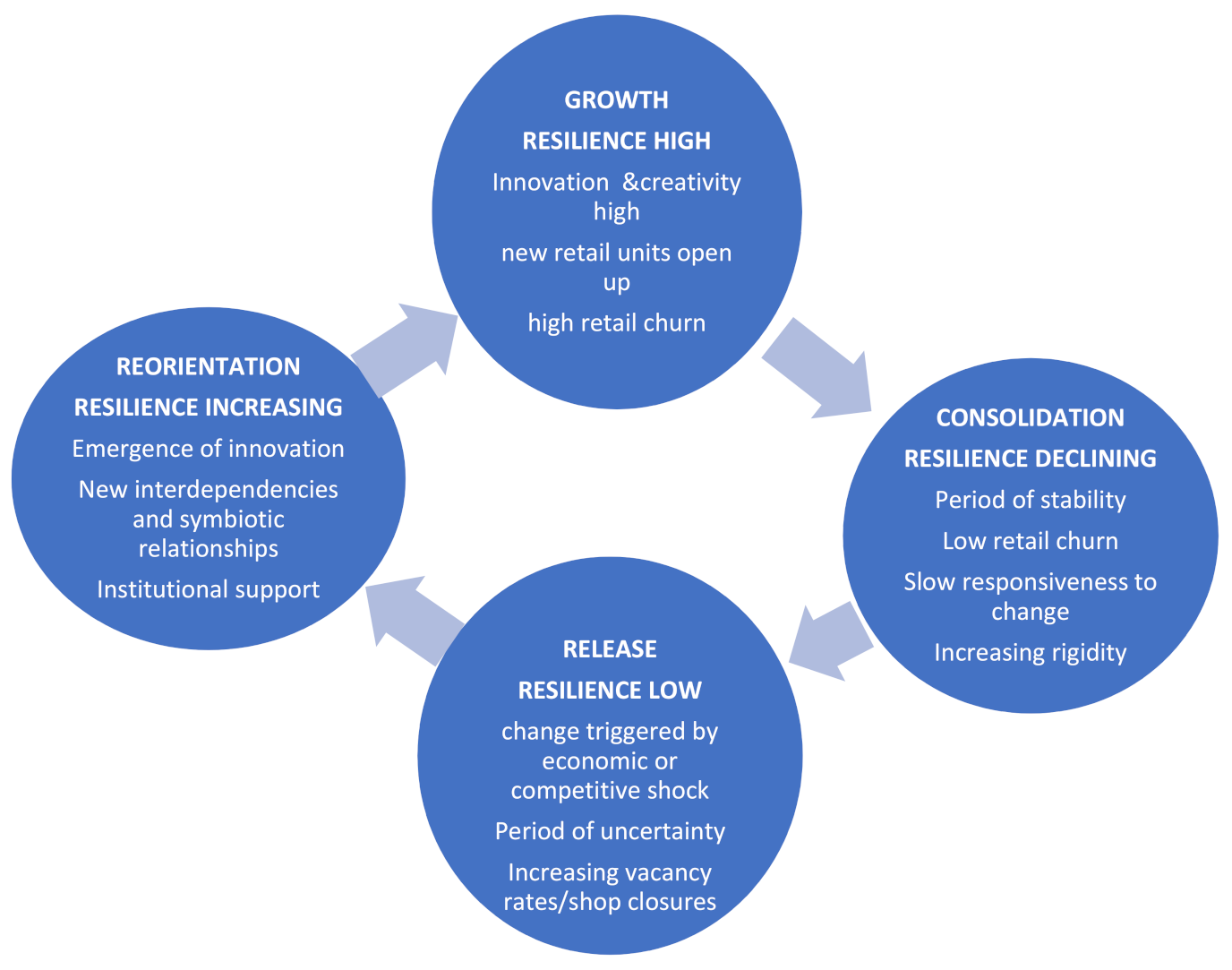

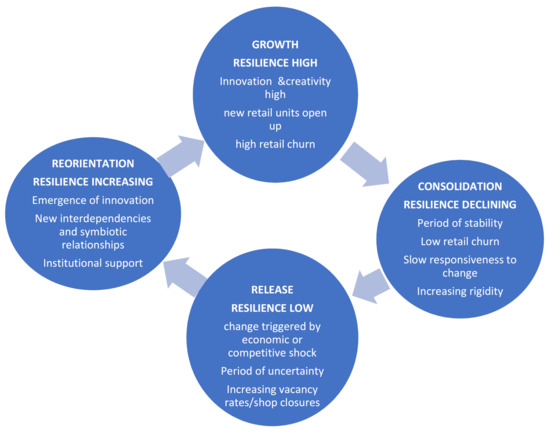

Celińska Janowicz and Dolega [49] have created an important theoretical framework for explaining how retail resilience can transform due to the process of maturing, reacting to different kind of shocks or long-term changes. They have indicated four dimensions of the adaptive cycle: growth, consolidation, release and reorientation (Figure 2), and have analyzed it in the context of changes in retail centers.

Figure 2.

Adaptive cycle of retail centers. Source: [49].

The phase of growth is usually characterized by high dynamism. During this stage, a large number of new stores is opened, which intensifies the competition. At this stage, a lot of investment is realized. As a result, a new floor space is offered, which fulfils high demand. The level of innovation and creativity during this stage is high, as is the resilience. However, as the phase approaches maturity, resilience slowly decreases.

The phase of consolidation begins when the system becomes stable and its rigidity increases. The connectedness between various entities is intensive and the development path becomes fixed. However, consumers’ habits are changing constantly, and the level of competition is rising; retail centers have to constantly adapt to these processes or their resilience will decrease.

The stage of release is rapid and marked by uncertainty, usually triggered by some unexpected shock. In the case of city centers, the shock can be of an internal nature, such as opening of a new chain store. It might be also caused by external factors such as an economic crisis or the opening up of shopping mall. Such competition might result in a decline of sales in town-center shops or a movement of downtown retailers to the new mall. The number of shops in the city center decreases and new openings do not match it. As a result, the whole social and economic environment worsens. However, such a negative shock has the potential to reverse the rigidity of a development path as new chances for development emerge. The resilience in this phase is low.

During the last stage of reorientation, innovations appear and new growth potential is accumulated. Some new internal mechanisms appear, and as a result new configurations and interdependencies are created. The reconfigured town center regains the potential to increase its attractiveness, and as a result resilience increases.

4. Transition of Urban Retail System in Poland—Background

A comprehensive understanding of the changes to the urban retail system in Poland requires taking into account the system transformations of 1989. The reforms implemented at that time, and the adopted assumptions for economic development, permanently determined the characteristics of the retail sector in Poland [60].

One of the aspects of the economic transformation and the so-called shock therapy [4] was the massive privatization of state property [61]. This plan was implemented through liquidating or restructuring, as well as the privatization of state-owned enterprises, resulting in mass layoffs [62]. In order to avoid unemployment, many of the employees of these enterprises decided to start businesses in the retail trade. Such activities did not require any special qualifications, experience or significant start-up capital [60]. Thus, the place and offer of emerging commercial stands were often chosen randomly and spontaneously. Lack of competencies was not an obstacle to turning a profit in the face of the shortage of goods on the market after the decades of consumption overhang characteristic of the socialistic economy [63].

The stage of the domination of unprofessional merchants in the Polish market started to fade when the first shopping malls emerged in the late 1990s. [10] With the prospect of Poland’s accession to the European Union, foreign investors ascertained the market’s stability and legal security. For these reasons, there was an extremely rapid expansion of shopping malls, which revolutionized the existing retail structure in Poland [11]. Shopping malls have created a magical world of consumption [64,65]. Beautiful, clean, modern interiors and a wide selection of goods contradicted the rough 1990s, as well as the shortages of the communist period. From the very beginning, most of Polish society treated these facilities with great favor as places of consumption in line with their aspirations, which increased significantly during the period of increased prosperity in the 1990s. The local press praised shopping malls for the breath of modernity they brought to Polish cities, for their comprehensive commercial and service offer and for being a perfect place for shopping, socializing and entertainment for the whole family. Conversely, domestic merchants, especially from the high streets, swiftly recognized the threat and started to oppose the distribution by municipalities of permits for building shopping malls [11]. Meanwhile, since around 2010 the e-commerce sector has become stronger and stronger. Although its share in retail has grown steadily [20,21,24], its virtual form meant that it remained beyond the discussion of trade competitiveness for a long time.

6. The Changing Relationships within Urban Retail System

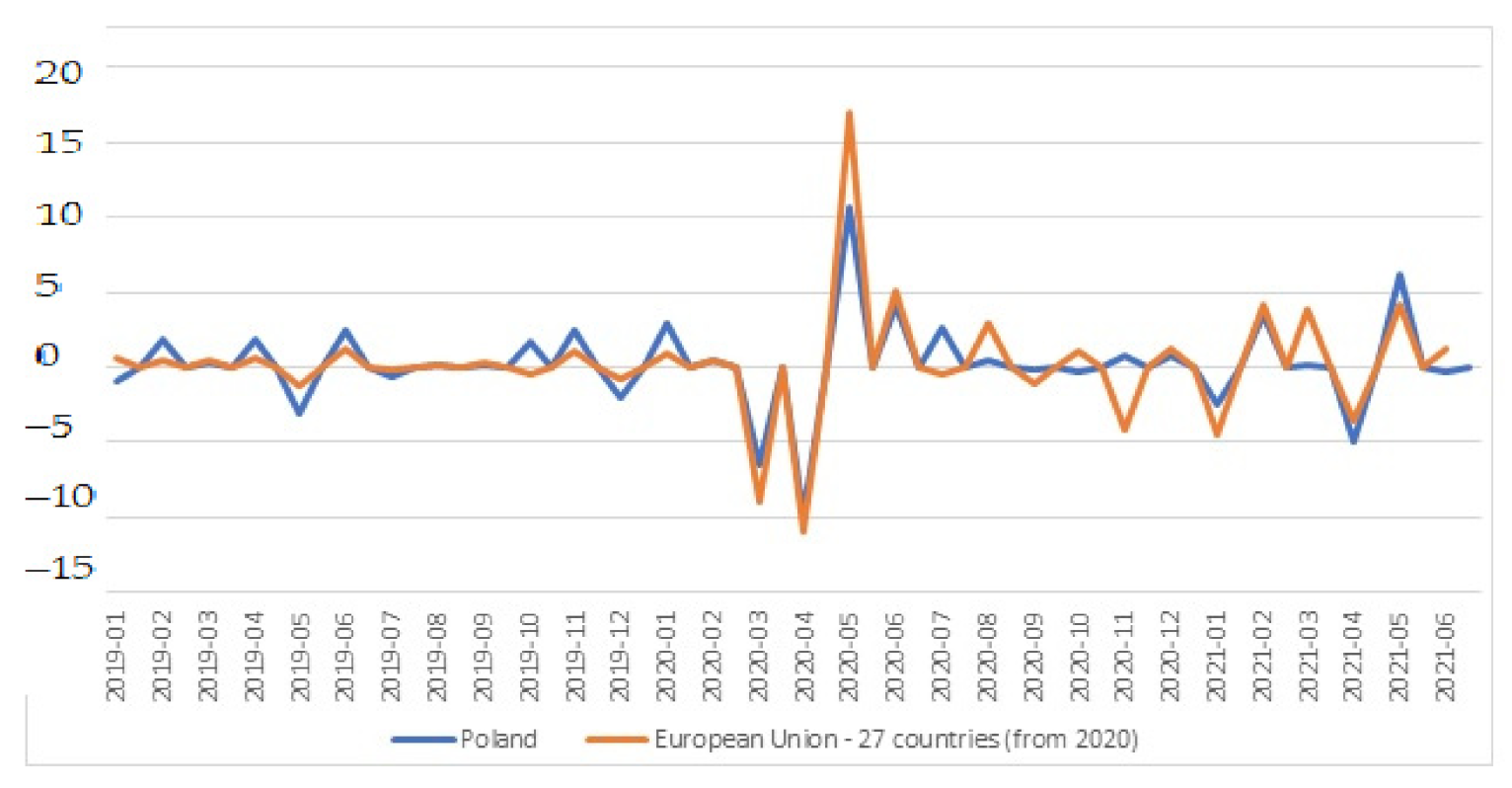

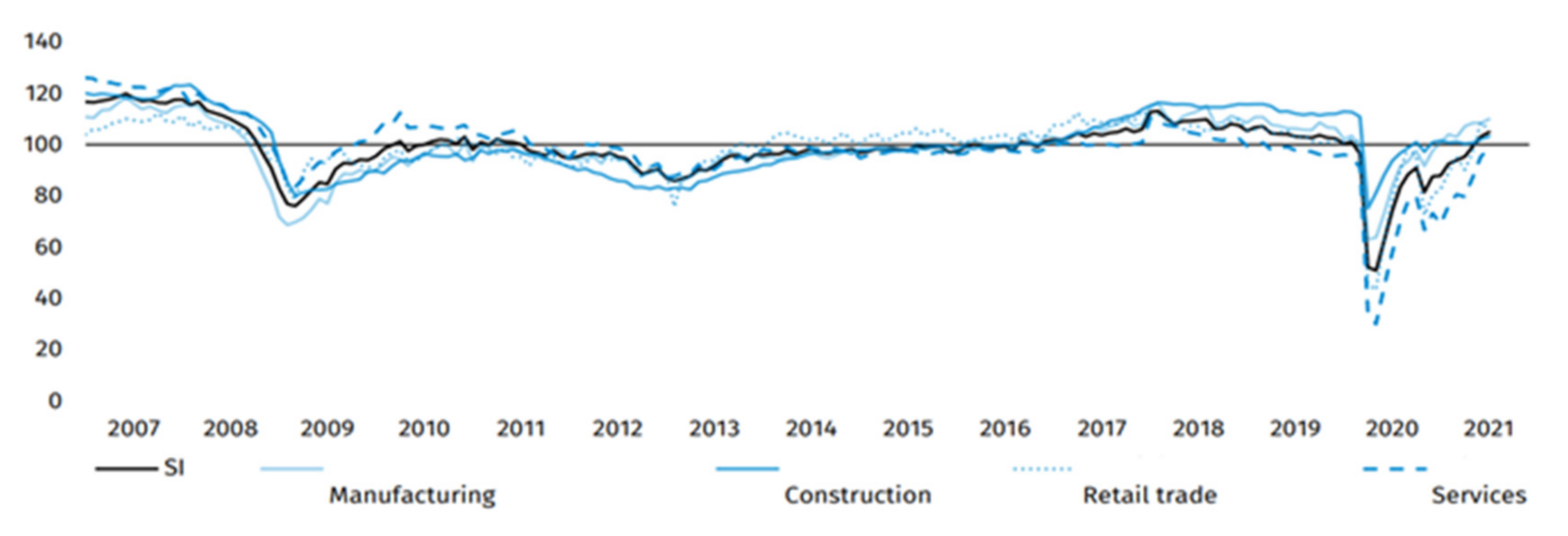

The fight against the coronavirus has particularly affected sectors such as retail trade, catering, entertainment, culture and sport. The introduced restrictions applied to a different extent to shopping malls and points of sales located on shopping streets. The problems faced by the retail trade sector reflected similarities to the general economic situation in Poland. In March 2020, it collapsed, which was felt most strongly in the service sector and in retail. The scale of its breakdown in 2020 compared to previous years is illustrated in the Figure 4.

Figure 4.

General synthetic indicator for Poland (SI) and its decomposition. Source: [1].

General synthetic indicator is composed out of manufacturing (50% of indicator), construction (6% of indicator), retail (6% of indicator) and services (38% of indicator).

6.1. Shaken Position of Shopping Malls

As a result of the pandemic, shopping malls, the strong position of which on the Polish market seemed steadfast by 2020, faced an existential threat. The fundamental problem faced by these facilities was the four-fold ban on commercial activities, which, in the period from March 2020 to October 2021, lasted almost five months overall (during that time, only supermarkets, pharmacies and cosmetic shops were allowed to open). The ban on the operation of catering services on-site lasted even longer, amounting to circa 9 months during whole pandemic period. Entertainment and cultural facilities were also closed. The limitation of these activities indirectly affected the retail sector, as they are highly complementary industries. A study of 140 shopping malls comparing attendance and turnover (per 1 sq m) in the period from January to 15 November 2020 (year-to-date) showed that the restrictions relating to the pandemic resulted in more significant losses among shopping malls with extensive entertainment and gastronomic offer rather than among less specialized facilities [21,74]. All the shopping malls surveyed recorded a decline in occupancy, the highest drops were experienced by the largest malls (−32.3%), becoming slightly smaller in medium-sized malls (−28.1%) and small malls (−26.8%). The decrease in attendance translated into financial results for tenants. At the end of September 2020, the average turnover per square meter was slightly higher in the largest malls and amounted to PLN 588.8, which meant a decrease of 26.5% compared to the corresponding period of 2019. In medium-sized shopping malls, the average turnover decreased by 22.2% compared to the previous year (and amounted to PLN 584.5); it decreased in the smallest malls by 26.1% and amounted to PLN 496.2 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Attendance and turnover of shopping malls in January-November 2020 compared to the period January-November 2019.

As a result of the pandemic and the introduced sanitary restrictions, customers of shopping malls significantly shortened their time spent in these facilities. While in January and February 2020, i.e., before the pandemic outbreak, the average time spent in the gallery was 68 min, in March this time dropped to 45 min. In the following months customers gradually extended their time spent in the shopping mall, reaching the pre-pandemic time of 68 min in June 2020, and reaching 75 min in August and September 2020 [75].

The dramatic deterioration of the conditions for running a business in shopping malls caused many tenants from retail chains to terminate some of their lease agreements or limit the size of the space leased. In addition, many tenants began to negotiate new, lower rents for commercial space leases, as the fees became too high concerning the market conditions of the economic downturn and an uncertain future. Despite an openness to renegotiating the contracts in official declarations, the shopping centers’ managements were not always willing to change the terms. In some cases, conflicts escalated to such a level that the owners of shopping malls decided to take the measure of illegal seizure of goods against rent [76]. In May 2020, when shopping malls were first reopened, 20% of commercial space remained closed due to a lack of agreement between tenants and the owners of shopping malls as to the content of their lease agreement, the amount of rent paid and the method of its calculation [77]. Due to the lack of an agreement with the owners, the chain companies Empik and LPP were the first to terminate the lease agreements, followed by Lancerto, Kazar, Ochnik, Giacomo Conti and Recman [78], as well as some entrepreneurs not associated with the networks.

The spring 2020 lockdown caused a decrease in the shopping mall industry revenues by over PLN 17.5 billion. The Autumn 2020 lockdown led to about PLN 8 billion of lost turnover. It is assessed that the closure of the economy would contribute to a gap in the industry’s turnover at the level of over PLN 4 billion. According to a representative of the Polish Council of Shopping Malls, the owners of these facilities in 2020 achieved revenues that were lower by over PLN 4.5 billion, which accounted for 45% of the value of their annual turnover [79].

As a consequence of prolonged lockdowns and problems with tenants, owners of shopping malls faced significant financial losses and, as a result, problems with the repayment of loans taken for their construction. Shopping malls are usually indebted at the level of 60–80% of their value, which depends on the capital intensity of their construction and their adopted business model. According to various estimates, the cost of servicing this debt ranges from PLN 1.9bn to PLN 3.2bn annually. These expenses, however, do not take into account the amount of loan principal repayment [80]. According to a representative of the Polish Council of Shopping Malls, the financial problems of shopping malls will lead to difficulties with debt repayment and may even contribute to an imbalance in the stability of the financial sector in Poland [79].

On 31 March 2020, the Polish government adopted an aid package for entrepreneurs [81], which also offered some aid to tenants in shopping malls and the owners of gastronomy entities. Tenants in shopping malls have been temporarily released from the obligation to pay rent to the owner of those shopping malls under the condition of submitting a declaration of intention to extend the lease for the prohibition period plus six months, in accordance with the existing provisions of the contract. Within 3 months of the lockdown abolition, the tenants could choose either to take advantage of the rent exemption linked to the contract extension or withdraw from the government’s aid [82]. In this framework, the obligation to extend the contract constituted compensation for the shopping malls for the incurred financial losses. The industry representatives criticized the regulations concerning the state aid for tenants for imprecise provisions and the questionable benefits of using it. The extension of the lease agreement on terms negotiated before the COVID-19 pandemic, in the face of the decline in occupancy in shopping malls and a significant economic downturn, was a solution unfavorable for tenants, merely postponing economic problems without solving them. However, some lawyers pointed out that under Art. 700 of the Civil Code the tenants may demand a reduction in rent if the income from the business were to significantly decrease for reasons beyond their control. According to lawyers, three months guaranteed to consider the possibility of extending lease agreements gave tenants the time necessary to work out solutions to the problem [82].

In November 2020, representatives of the shopping malls industry drew attention to the fact that the entire industry needs support; the following methods of assistance were mentioned: tax and social insurance reliefs and the suspension of loan repayment instalments for tenants and owners of shopping centers. They emphasized that for the survival of them and their contractors, it would be necessary to abandon further lockdowns [74]. Throughout the pandemic, representatives of shopping centers called for the restoration of trading Sundays (in 2020, a law limiting the possibility of trading on Sundays to a few Sundays a year came into force in Poland). According to one of the centers conducting research on the functioning of the retail industry, a permit to conduct commercial activities seven days a week would be the cheapest way to support the industry. It would also increase the safety of buying, as it would reduce the density of customers in stores [21]. Retail Institute estimated that the possibility of trading on Sunday would result in 4%. increased footfall in stores and a 2% increase in turnover [83].

6.2. Shopping Streets and Its’ Future

The crisis of high streets in Poland and abroad has been discussed for a long time in the literature [2,47,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93]. Most authors see the main driver of this phenomenon as a growing competition from modern shopping centers located in downtown areas and e-commerce development [88,91]. The pandemic created favorable conditions for even more robust growth of e-commerce at the cost of high streets. Lockdowns were accompanied by limitations on social mobility, working and studying remotely, decreased number of business meetings and lunches and a decline in tourist traffic [13,16,17,19]. Moreover, public space began to be perceived as a potential site of contamination, and therefore a dangerous space, time spent in which should be minimized. Public space quickly became a transit space [94].

Initially, the pandemic had a clear negative impact on downtown shopping streets [95]. In the long run, however, it cannot be ruled out that the pandemic will prove to provide a chance for their recovery. Several lockdowns have shown that commercial activity in shopping centers carries risks that no one had previously anticipated. Losses of entrepreneurs operating in shopping centers as a result of lockdowns prompted them to diversify distribution channels, especially in the retail trade and the gastronomy sector [95,96,97,98]. Downtown shopping streets have once again become an attractive alternative to shopping malls. Industry reports forecast the development of new commercial formats that are intimate and multi-functional, essentially constituting small shopping malls located on main shopping streets [96]. The pandemic has proved to have a positive impact on shopping streets in residential areas. People became accustomed to the pandemic conditions, spending more time in their place of residence and doing everyday shopping there. This increased the importance of shops and service outlets located near housing estates [95].

6.3. Development of e-Commerce

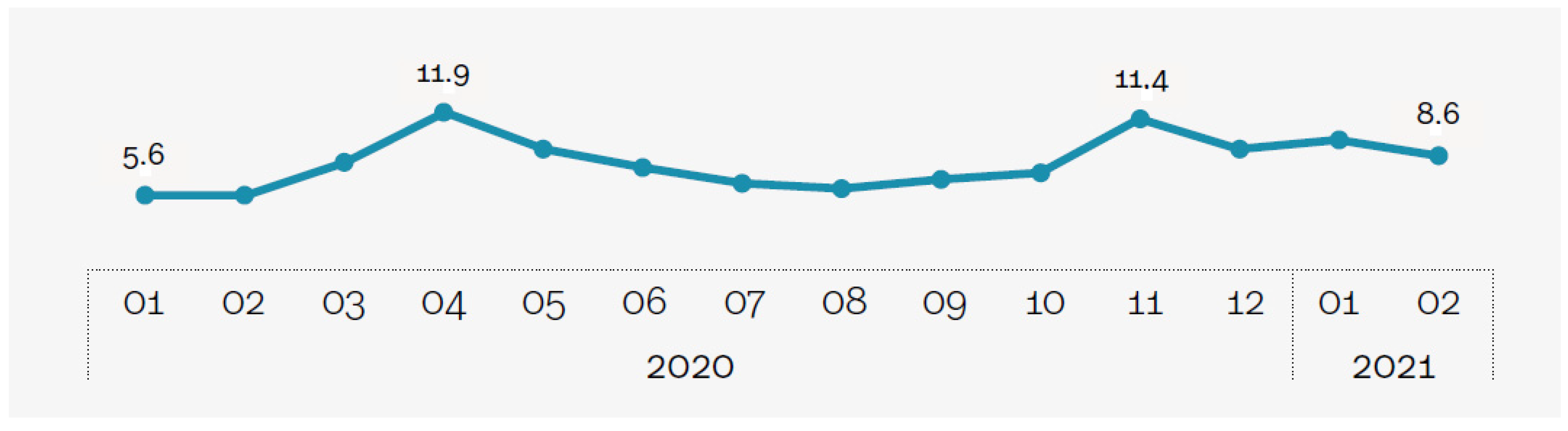

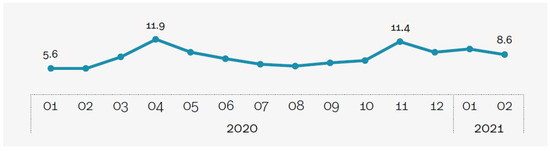

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant and very positive impact on the development of the e-commerce distribution channel. However, the speed of development of this sector during the pandemic was not the same at all times, and different parts of the sector benefited to different extents [22,99]. The importance of the e-commerce sector in total retail sales can be estimated on the basis of changes in several indicators: the value of online sales, the share of e-commerce in total retail sales, the number of people buying online and the number of online stores. The gross value of goods sold online has grown steadily since 2017 at a rate of 18%. In 2020, this growth accelerated; its pace amounted to 35%, and the value of goods sold online reached the value of PLN 83 billion. Industry reports forecast further systematic growth of the e-commerce sector; its pace will amount to 12%. When analyzing the share of online sales in total retail sales (Figure 5), one can observe a clear relationship between successive lockdowns and the value of on-line shopping. Reducing sanitary restrictions and unfreezing the economy resulted in a significant number of consumers returning to stationary forms of sale. In January 2020, the share of e-commerce in total retail sales in Poland was 5.6%. During the first lockdown in April 2020, this rate increased to 11.9%. From May to July 2020, the share of Internet sales in total retail sales in Poland decreased in August 2020 before beginning to grow again, reaching a share of 11.4% in November 2020, when the government introduced a stricter sanitary regime and closed shopping malls. In the period January–February 2021, the value of online sales remained at the peak level of 9% of the value of all retail sales [22].

Figure 5.

Online sales share in total retail sales in Poland (%). Source: [22].

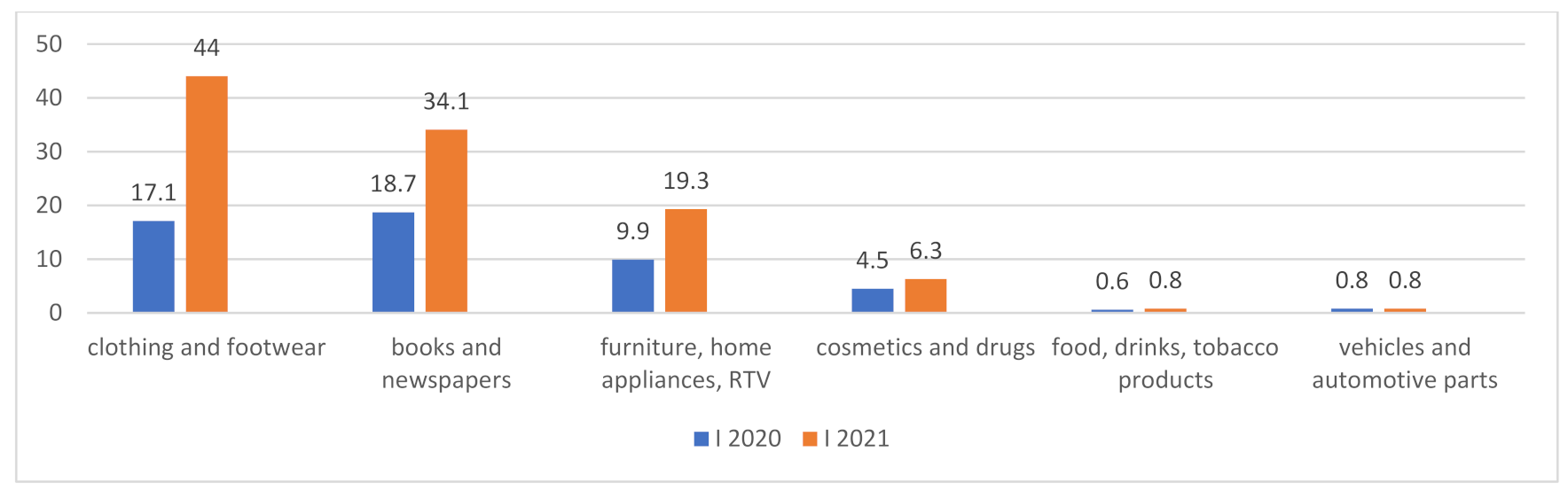

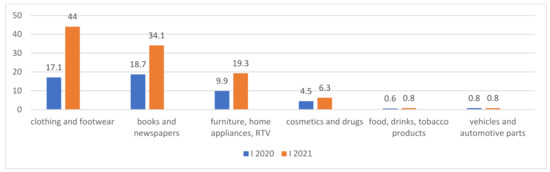

The value of e-commerce sales varied depending on the industry (Figure 6). During the pandemic, in the clothing, bookstore, furniture, electronics and household appliances sectors, the share of e-commerce sales increased significantly. Internet sales of food were negligible. It can be noticed that the industries benefitting from the significant online sales growth prior to the pandemic were also leaders of growth after the COVID-19 outbreak. In the case of cosmetics, vehicles and parts, food and tobacco, the pandemic did not change so much. The online sales growth was relatively rapid, though customers predominantly still preferred to buy these categories stationarily.

Figure 6.

Online sales share in total retail sales in Poland (%), according to industry. Source: [22].

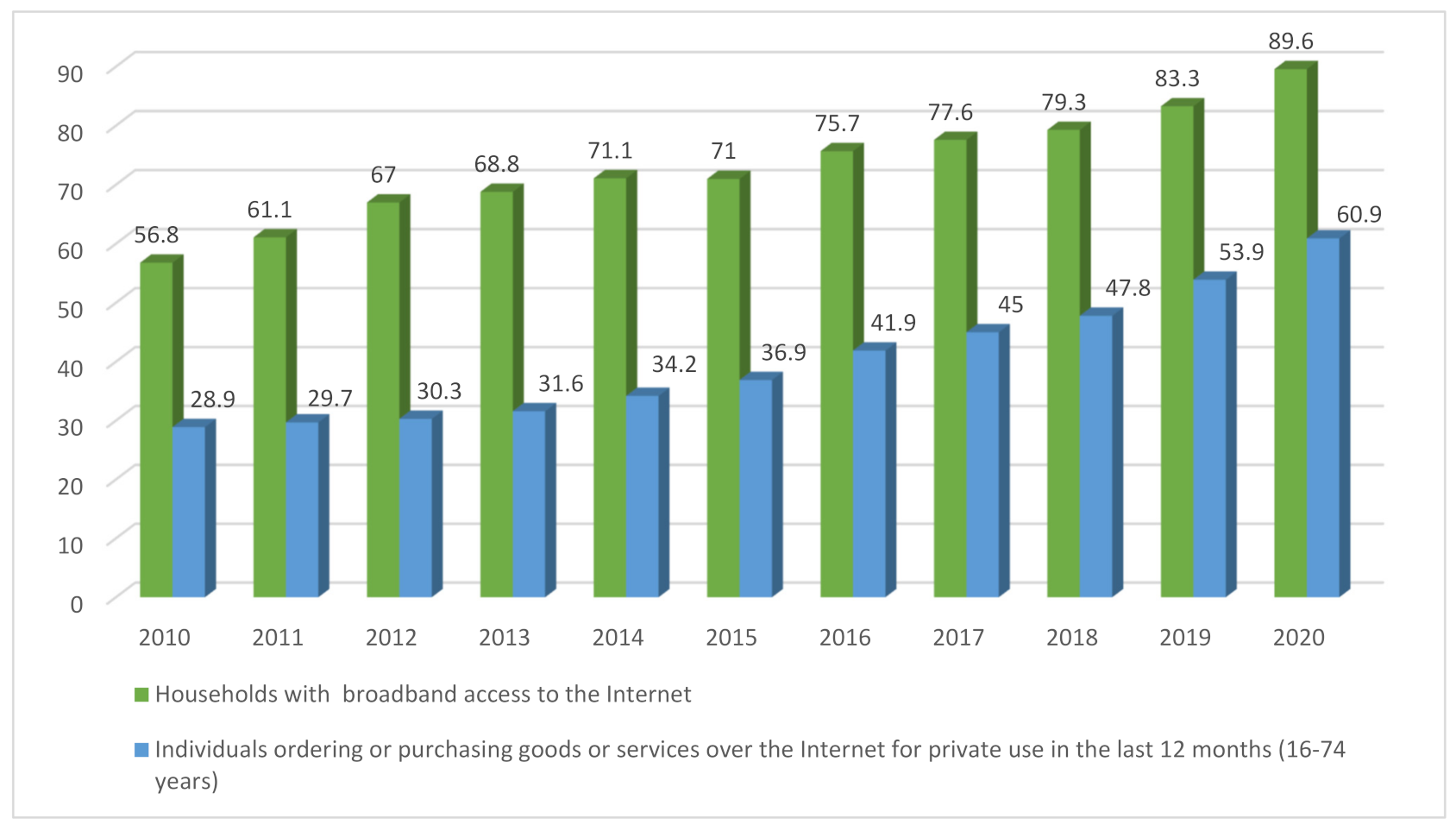

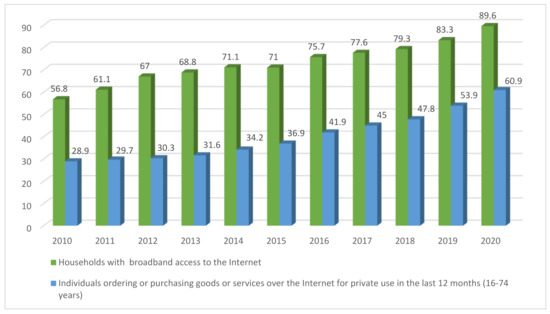

When assessing the scale of the e-commerce market growth under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important not to overlook the role of internet infrastructure development. In recent years, the access of households to broadband in Poland has significantly improved, and the share of e-commerce customers followed this pattern (Figure 7). The chart shows a clear, stable upward trend both in terms of broadband Internet access and the percentage of people buying online. A particularly rapid increase in both values was recorded after 2018, when the increase in the number of online buyers amounted to 6.1 percentage points. In 2020, this percentage increased by another 7 percentage points, reaching a value of almost 61 percent.

Figure 7.

Access to the Internet and share of people purchasing on-line. Source: [2,20,21].

According to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, almost 85% of Poles, even after the end of the pandemic, do not plan to reduce the frequency of their online purchases. 10% of those surveyed intend to increase it, in fact, and 82% of respondents declared that they would spend the same or more on e-shopping in 2021 compared to their 2020 spending [24].

The increase in the number of online shoppers and the share of online sales in total retail sales is accompanied by a steady increase in the number of online stores. The upward trend clearly accelerated after 2018, when 28,900 online stores were operating in Poland. In 2019, the number increased by 7700 to 36,600. In 2020, there were 44,500 stores in Poland, which was 7900 more than in 2019 [100].

The dynamic increase in the share of trade over the Internet was facilitated by earlier investments by enterprises from the retail sector in modern technological and logistic solutions. Some industries, e.g., clothing, treated the development of e-commerce as one of their development goals even before the pandemic [101]. Administrative restrictions on stationary sales, as well as changing shopping habits due to the pandemic, made a large group of customers, e.g., those from older age groups [99], try to do shopping on the Internet, and stores operating so far only in the traditional channel noticed the advantage of diversifying their distribution channels [19]. The changes forced by the pandemic will to some extent become permanent, which is confirmed by the conclusions of the McKinsey report. According to this, consumers like to stick to new habits that have worked well [24,27]. In this context, the pandemic only accelerated a process that had already proceeded long before. It should also be noted that the dynamic development of the online sales channel did not take place spontaneously; it was favored by, among others, government agencies. An example of this could be the following social campaign organized by the state Industry Development Agency: “Bring your company to the Internet. Earn money on e-commerce”, which was launched in April 2020. The program encouraged companies to start selling online, as well as providing substantive tips and information on how to start such an activity. The campaign was supported by the largest e-commerce platforms in Poland such as OLX and Allegro [102].

7. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The COVID-19 pandemic constitutes a unique occasion on which to conduct a stress-test of retail resilience concepts in the lively organism of a city. It delivers a useful framework for analyzing processes occurring in the Polish retail trade. The undertaken research contributes to these concepts by indicating how the shock of COVID-19 could affect components of the urban retail system in ambivalent way as they express different levels of resilience. Some elements of the system had no problems with adjustments to the shock of the pandemic, whereas others with more rigid structures had problems with adaptation.

Shopping streets, malls and e-commerce in Poland before the outbreak of the pandemic were all at different stages of the adaptive cycle. The shock of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed relations within urban retail systems. It has shaken the position of the dominant player, i.e., shopping malls [98,103], and has created new development opportunities for coping with stagnating shopping streets [94,95,96]. Eventually, the pandemic turned out to be a booster for e-commerce growth [13,22,99] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Adaptive cycle of urban retail system in Poland in 2021. Source: own study.

Before the outbreak of the pandemic, the e-commerce sector in Poland was already at a stage of growth [20,21,23,24] and its resilience was high. The consequences of COVID-19, such as lockdowns, reduced mobility of people, social isolation and fear of contagion risk, only strengthened e-commerce growth [19,22,99]. However, this growth would not have been possible without the previous investments, prior to the pandemic, of online stores in logistics, infrastructure and security [19,24,101], as well as the introduction of new, improved online selling conditions (usually better than in traditional stores) [24]. Among the most important amenities were the offer of quick, cheap or free deliveries and an extended time for returning the product. These competitive advantages of online shops during the pandemic led to the emergence of many new entrants on the e-commerce market [100].

Shopping malls in Poland were the undisputed market leaders in the retail sector until the COVID-19 pandemic. They were at a growth phase of the adaptive cycle. However, as this phase approached maturity, new growth problems emerged, constituting derivatives of shopping malls’ success. The growing total retail space as a consequence of new shopping malls’ openings [104] increased the competition intensity [105]. Many tenants in these facilities, in particular small local entrepreneurs, were dissatisfied with the ratio of profits to rental fees. The lease conditions made it impossible for them to terminate contracts before the lapse of usually five years from signing [106]. The owners of shopping malls did not react to the growing dissatisfaction of tenants with selling conditions. The introduction of the ban on Sunday trade by the Polish government [107,108,109] and continuous e-commerce competition [24] further aggravated the conditions of shopping mall tenants. The impact of COVID-19 on shopping malls was clearly negative, mainly due to temporary forced closure periods and restrictions on gastronomy, culture, sports and entertainment services, but also due to customer fear of contagion [75,79,80,82,83]. Many dissatisfied tenants used the pandemic as an excuse to terminate contracts with shopping malls or negotiate more favorable selling conditions [76,77,78]. Entrepreneurs who hadn’t imagined doing business outside shopping malls after the pandemic noticed the need for more diversification by selling in high streets and using e-commerce channels [95,96,97]. The pandemic revealed problems with financial sustainability for the owners of shopping malls. Their high level of indebtedness exposed the risks of financing them to their banks, which also significantly limited shopping centers’ flexibility in offering better conditions to frustrated tenants [79,80].

It can be stated that the resilience of shopping malls is declining, and that they are entering a consolidation stage of the adaptive cycle. However, the impact of COVID-19 on shopping malls differs dependent on the variety of offered services. A new generation of shopping malls with a wide range of entertainment and gastronomy services, as well as shopping malls located in downtowns, turned out to be much more vulnerable to the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic than district shopping malls and those of the older generation with a simple commercial offer [21,74].

High streets seem to be the weakest link in the urban retail system in Poland. Until the end of the 1990s, they were in the growth phase, and the number of merchants was dynamically growing. In the following years, competition from shopping malls and e-commerce grew steadily. The COVID-19 pandemic further decreased the market competitiveness of high streets, especially in downtown areas [95]. Due to their focus on gastronomy, they were particularly affected by the counter-pandemic measures, such as home office working and remote education, lack of business meetings and lack of tourists. On the contrary, the influence of COVID-19 on shopping streets in residential areas was slightly positive, with people spending more time at home starting to fulfil their needs in areas located in their living areas [95]. Before the pandemic outbreak, the shopping streets in Poland were at a release stage of the adaptive cycle and their resilience was low. In the longer term, some positive trends are predicted. Many chain stores will move out of shopping malls and will take into account high streets as a potential location. At the same time, the trend of the revival shopping streets in residential areas, which has already started, will be continued [95,96,97].

The retail resilience concept, which was created after the global financial crisis to analyze its consequences, has not been developed too intensively since then, though during the global pandemic it proved its utility once more. It would be therefore valuable to continue elaborating on this concept, comparing retail resilience in various countries and looking for sustainable models for the development of retail trade in downtown areas and shopping streets, and taking into account threats the coming from e-commerce expansion. Otherwise there is a risk of getting back to the era of crisis for city centers which will weaken the whole structure of cities. In this way, the pandemic could be a real contagion of faulty development, which could destabilize cities for decades to come.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted many of the problems cities have faced for years. They can be marked as the effects of unsustainable development, which increasingly affects cities and their inhabitants [110,111]. As a result of the pandemic, people began to consider anew how to organize their lives in cities in order to make those cities more sustainable and allow their inhabitants to be less exposed to sanitary risks [110].

To ensure the well-being and viability of city dwellers, sustainable retail development is necessary. This assumes balancing the size structure of retail entities and ensuring equal access to them for various social groups [32,52,53,54]. The way to improve the sustainability of the urban retail system in Poland is to strengthen the importance of high streets, as well as shopping streets in residential areas. In the discussion on the recovery of high streets, the need to manage their space as one economic entity, conducting marketing activities aimed at business and customers is emphasized. As a result, entrepreneurs would like to run shops along the streets, and customers would like to come there. The literature emphasizes the need for participatory development of a vision for the development of shopping streets, reinventing them to meet the needs of customers in the 21st century and to compete with e-commerce and shopping malls [19,103]. Perhaps the solution to the problem of falling competitiveness of high streets in Poland would be the introduction of a concept known in Western Europe as Business Improvement Districts [2].

Funding

This research was funded by SGH Warsaw School of Economics.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Statistics Poland. Business Tendency in Manufacturing, Construction, Trade and Services 2000–2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/business-tendency/business-tendency/business-tendency-in-manufacturing-construction-trade-and-services-2000-2021-november-2021,1,56.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Silva, D.G.; Cachinho, H. Places of Phygital Shopping Experiences? The New Supply Frontier of Business Improvement Districts in the Digital Age. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziszewska, J. Przemiany przestrzeni konsumpcji w polskich miastach po 1989 roku. In Przestrzeń Społeczna Miast i Metropolii w Badaniach Socjologicznych; Rykiel, Z., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego: Rzeszów, Poland, 2014; pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Skodlarski, J.; Pieczewski, A. Przesłanki transformacji polskiej gospodarki 1990–1993. Studia Prawno-Ekonomiczne. 2011, 83, 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Błachucki, M. Liberalizacja zasad działalności gospodarczej. In Transformacja Systemowa w Polsce; Żukrowska, K., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Żukrowska, K. (Ed.) Liberalizacja wymiany handlowej-decentralizacja i demonopolizacja. In Transformacja Systemowa w Polsce; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 401–417. [Google Scholar]

- Żukrowska, K. (Ed.) Liberalizacja przepływu kapitału. In Transformacja Systemowa w Polsce; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 417–427. [Google Scholar]

- Czarzasty, J. Stosunki Pracy w Handlu Wielkopowierzchniowym w Polsce; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, R. Raport 2 Poł. 2014 r; Retail Research Forum. Available online: https://prch.org.pl/pl/baza-wiedzy/24-retail-research-forum/80-raport-prch-rrf-ii-pol-2014 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Radziszewska, J. Przemiany centrów handlowych w Polsce. In Zmieniający Się Świat. Perspektywa Demograficzna, Społeczna i Gospodarcza; Osiński, J., Pachocka, M., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; pp. 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Popławska, J. Rynki, Ulice i Galerie Handlowe. Polityka Publiczna Wobec Miejskich Przestrzeni Konsumpcji w Polsce; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, A.; Jarczewski, W.; Koj, J.; Mróz, M.; Mucha, A.; Sykała, Ł. Rewitalizacja centrów miast. In Raport o Stanie Polskich Miast. Rewitalizacja; Jarczewski, W., Kułaczkowska, A., Eds.; IRMiR: Warsaw-Krakow, Poland, 2019; pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, J.; Frommeyer, B.; Schewe, G. Online Shopping Motives during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Lessons from the Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degli Esposti, P.; Mortara, A.; Roberti, G. Sharing and Sustainable Consumption in the Era of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frago, L. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Retail Structure in Barcelona: From Tourism-Phobia to the Desertification of City Center. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. COVID-19 Restriction Measures—DG ECHO Daily Map. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/map/italy/european-union-covid-19-restriction-measures-dg-echo-daily-map-20042020 (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- European Union. Joint European Roadmap towards Lifting COVID-19 Containment Measures. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/pl/publication-detail/-/publication/14188cd6-809f-11ea-bf12-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Sommella, R.; D’Alessandro, L. Retail Policies and Urban Change in Naples City Center: Challenges to Resilience and Sustainability from a Mediterranean City. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PWC. Gdzie Będą Kupować Polacy—Lokalizacja Handlu w Czasach Niepewności. Available online: https://www.pwc.pl/pl/artykuly/gdzie-beda-kupowac-polacy-lokalizacja-handlu-w-czasach-niepewnosci.html (accessed on 6 January 2020).

- Statistics Poland. Koniunktura Konsumencka—Lipiec 2021. Informacje Sygnalne. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/koniunktura/koniunktura/koniunktura-konsumencka-lipiec-2021-roku,1,101.html (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Retail Institute. Stanowisko Przedsiębiorców Skupionych Wokół Retail Institute w Sprawie Niedziel Handlowych. Available online: https://einstitute.com.pl/stanowisko-przedsiebiorcow-skupionych-wokol-retail-institute-w-sprawie-niedziel-handlowych/ (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Miniszewski, M.; Dębkowska, K.; Kolano, M.; Śliwowski, P. Konsumpcja w Pandemii; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, M. Information Society in Poland in 2020; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, M.; Steinhoff-Traczewski, M.; Tzanow, A. Strategie Które Wygrywają. Liderzy E-Commerce o Rozwoju Handlu Cyfrowego. Available online: https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:dS-tL2UavkUJ:https://www.pwc.pl/pl/publikacje/liderzy-e-commerce-o-rozwoju-handlu-cyfrowego.html+&cd=1&hl=pl&ct=clnk&gl=pl (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Statistics Poland. Społeczeństwo Informacyjne w Polsce. Wyniki Badań Statystycznych z Lat 2010–2014. Available online: http://kigeit.org.pl/FTP/PRCIP/Literatura/113_spoleczenstwo_informacyjne_w_polsce_2010-2014.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Statistics Poland. Społeczeństwo Informacyjne w Polsce. Wyniki Badań Statystycznych z Lat 2015–2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/nauka-i-technika-spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne-w-polsce-wyniki-badan-statystycznych-z-lat-2015-2019,1,13.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Kohli, S.; Timelin, B.; Fabius, V.; Moulvad Veranen, S. How COVID-19 Is Changing Consumer Behaviour—Now and Forever. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/how-covid-19-is-changing-consumer-behavior-now-and-forever (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- PWC. Nowy Obraz Polskiego Konsumenta. Postawy i Zachowania Polaków w Obliczu Pandemii Koronawirusa. Available online: https://www.pwc.pl/pl/publikacje/nowy-obraz-polskiego-konsumenta.html (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- WHO. Influenza—Past Pandemics. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/pandemic-influenza/past-pandemics (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Cherry, J.D. The chronology of the 2002–2003 SARS mini pandemic. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2004, 5, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Guimarães, P. Public Policy for Sustainability and Retail Resilience in Lisbon City Center. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hudson, R. Resilient regions in an uncertain world: Wishful thinking or a practical reality? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2009, 3, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, A.; Dawley, S.; Tomaney, J. Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmie, J.; Martin, R. Editor’s choice: The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, R.L. Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 12, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, N.; Dolega, L. Resilience, fragility, and adaptation: New evidence on the performance of UK high streets during global economic crisis and its policy implications. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 430, 2337–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata-Salgueiro, T.; Erkip, F. Retail planning and urban resilience—An introduction to the special issue. Cities 2014, 36, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erkip, F.; Kizilgun, O.; Mugan Akinci, G. Retailers resilience strategies and their impacts on urban space in Turkey. Cities 2014, 36, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karrholm, M.; Nylund, K.; de la Fuente, P.P. Spatial resilience and urban planning: Addressing the interdependence of urban retail areas. Cities 2014, 36, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachinho, H. Consumerscapes and the resilience assortment of urban retail systems. Cities 2014, 36, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandes, J.R.; Chamusca, P. Urban policies, planning and retail resilience. Cities 2014, 36, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. Downtown resilience: A review of recent (re)developments in Tempe, Arizona. Cities 2014, 36, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuduru, B.H.; Varol, C.; Yalciner Ercoskun, O. Do shopping centres abate the resilience of shopping streets? The co-existence of both shopping venues in Ankara, Turkey. Cities 2014, 36, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nüchter, V.; Abson, D.J.; von Wehrden, H.; Engler, J.-O. The Concept of Resilience in Recent Sustainability Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, L. Towns, High Streets and Resilience in Scotland: A Question for Policy? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, A.; Hardaker, S. Strategies in Times of Pandemic Crisis—Retailers and Regional Resilience in Würzburg, Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolega, L.; Celińska-Janowicz, D. Retail resilience: A theoretical framework for understanding town centre dynamics. Studia Reg. Lokalne 2015, 2, 8–31. [Google Scholar]

- Replacis, Retail Planning for Cities Sustainability, Final Rep. 2011. Available online: https://portal.research.lu.se/en/projects/replacis-retail-planning-for-cities-sustainability (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Sustainability. Special Issue Regional Resilience—Opportunities for Sustainable Development in Times of Crisis. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/regional-development. (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (ODPM). Planning Policy Statement 6: Planning for Town Centres (PPS6). Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20120919132719/http:/www.communities.gov.uk/documents/planningandbuilding/pdf/147399 (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Department for Communities and Local Government. Planning Policy Statement 4: Planning for Sustainable Economic Growth. Available online: http://www.knowsley.gov.uk/pdf/PG07_PlanningPolicyStatement4-Planning-for-SustainableEconomicGrowth.pdf. (accessed on 27 November 2021).

- Cachinho, H.; Salgueiro, T.B. Os sistemas comerciais urbanos em tempos de turbulência: Vulnerabilidades e níveis de resiliência. Finisterra 2016, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Folke, C. Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social-Ecological Systems Analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystem and People in a Changing World; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fujie, R. Resilient Forms of Shopping Centers Amid the Rise of Online Retailing: Towards the Urban Experience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramos, G.C.D.; Guibrunet, L. Assessing the ecological dimension of urban resilience and sustainability. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2017, 9, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiuk, A. Handel Detaliczny Jako Pracodawca We Współczesnej Gospodarce; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliński, J. Prywatyzacja. In Transformacja Systemowa w Polsce; Żukrowska, K., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Błędowski, P. Bezrobocie. In Transformacja systemowa w Polsce; Żukrowska, K., Ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kornai, J. Economics of Shortage; North Holland Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G. Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Continuity and Change in the Cathedrals of Consumption, 3rd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Makowski, G. Świątynia Konsumpcji. Geneza i Społeczne Znaczenie Centrum Handlowego; Trio: Warsaw, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sprawdziliśmy jak Pandemia Wpływa na Produkcję i Sprzedaż. 5 March 2020. Available online: https://przemyslprzyszlosci.gov.pl/sprawdzilismy-jak-epidemia-wplywa-na-produkcje-i-sprzedaz/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- McKinsey & Company. How COVID-19 Is Changing the World of Beauty. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Consumer%20Packaged%20Goods/Our%20Insights/How%20COVID%2019%20is%20changing%20the%20world%20of%20beauty/How-COVID-19-is-changing-the-world-of-beauty-vF.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Związek Przedsiębiorców i Pracodawców. Podsumowanie Lockdown-u w Polsce. 2021. Available online: https://zpp.net.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/25.01.2021-Business-Paper-Podsumowanie-lockdownu-w-Polsce.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Strona Internetowa: Koronawirus: Informacje i Zalecenia. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/aktualne-zasady-i-ograniczenia (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Statistics Poland. Koniunktura Konsumencka—Maj 2019 r. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/koniunktura/koniunktura/koniunktura-konsumencka-maj-2019-roku,1,75.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Statistics Poland. Koniunktura Konsumencka—Grudzień 2020 r. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5516/1/94/1/koniunktura_konsumencka__xii_2020_r.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Statistics Poland. Koniunktura Konsumencka—Kwiecień 2020 r. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/koniunktura/koniunktura/koniunktura-konsumencka-kwiecien-2020-roku,1,86.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Statistics Poland. Koniunktura Konsumencka—Grudzień 2020. Informacje Sygnalne. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/koniunktura/koniunktura/koniunktura-konsumencka-grudzien-2020-roku,1,94.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Otwarcie Centrów Handlowych. Retail Institute: Potrzebne Wsparcie dla Branży i Powrót do Niedziel Handlowych, forsal.pl, 22 November 2020. Otwarcie Centrów Handlowych. Available online: https://forsal.pl/biznes/handel/artykuly/8017616,otwarcie-centrow-handlowych-wsparcie-dla-branzy-powrot-do-niedziel-handlowych.html (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Kicińska, A.; Wojdat, D. Czy w Pandemii Centra są Handlowe? Available online: https://www.ey.com/pl_pl/strategy-transactions/czy-w-pandemii-centra-sa-handlowe (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Szymaniak, P. Galeriach Handlowych Kipi od Konfliktów. Dochodzi Nawet Do Zajęcia Towarów. Available online: https://gospodarka.dziennik.pl/news/artykuly/7715206,galeria-handlowa-spory-finanse-panstwo-rzad-pis-koronawirus-covid-19-odmrazanie-gospodarki.html (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Otto, P. Centra Handlowe Kontra Najemcy. Czy Wielu Galeriom Grozi Zamknięcie? Available online: https://gospodarka.dziennik.pl/finanse/artykuly/7690348,galerie-handlowe-gospodarka-kryzys-warunki-najmu-zmiany-koronawirus-covid-19-pandemia.html (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Pallus, P. Sieci idą na Wojnę z Galeriami. Firm, Które nie Otworzyły Sklepów, nie Jest Jednak Dużo. Available online: https://businessinsider.com.pl/finanse/handel/ktore-sklepy-reserved-empik-cropp-house-sa-otwarte/bklc7ny (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Trzeci Lockdown Zmniejszy Przychody Centrów Handlowych o Ponad 4 mld zł. Available online: https://forsal.pl/biznes/handel/artykuly/8063439,trzeci-lockdown-zmniejszy-przychody-centrow-handlowych-o-ponad-4-mld-zl.html (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Ochrymowicz, T.; Stojek, D.; Matysiak-Szymańska, M.; Lisicki, A.; Domański, P.; Bojdo, F. Wpływ Pandemii COVID-19 na Polski Rynek Centrów Handlowych. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/pl/pl/pages/real-estate0/articles/raport-galerie-handlowe-covid19.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Ustawa z Dnia 31 Marca 2020 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Szczególnych Rozwiązaniach Związanych z Zapobieganiem, Przeciwdziałaniem i Zwalczaniem COVID-19, Innych Chorób Zakaźnych Oraz Wywołanych Nimi Sytuacji Kryzysowych Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20200000374/U/D20200374Lj.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Ojczyk, J. Specustawa Zwalania Najemców z Czynszu Dla Galerii. Available online: https://www.prawo.pl/biznes/czynsz-za-najem-w-galeriach-handlowych-pakiet-antykryzysowy,499087.html (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Branża Handlowa: Powrót do Handlowych Niedziel Bardzo Potrzebny! Available online: https://www.wiadomoscihandlowe.pl/artykul/retail-institute-powrot-do-handlowych-niedziel-bardzo-potrzebny. (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Dawson, J.A. Futures for the High Street. Geogr. J. 1988, 154, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P. The Battle for the High Street. The Retail Gentrification, Class and Disgust; Palgrave McMillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Portas, M. The Portas Review. An independent Review into the Future of our High Streets; Mary Portas: London, UK, 2011. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/6292/2081646.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Roberts, M. The Crisis in the UK’s High Streets: Can the Evening and Nighttime Economy Help? J. Urban Res. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. The existential crisis of traditional shopping streets: The sun model and the place attraction paradigm. J. Urban Des. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Jackson, C. Death of the high street: Identification, prevention, reinvention. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2015, 2, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrigley, N.; Lambiri, D. British High Streets: From Crisis to Recovery? A Comprehensive Review of the Evidence. Available online: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/375492/1/BRITISH%2520HIGH%2520STREETS_MARCH2015%2528V2%2529.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Wrigley, N.; Brookes, E. Evolving High Streets: Resilience and Reinvention—Perspectives from Social Science. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268509097_Evolving_high_streets_resilience_and_reinvention_-_perspectives_from_social_science (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Kefford, A. The Death of the High Street’: Town Centres from Post-War to Covid-19. History Policy. Available online: https://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/the-death-of-the-high-street-town-centres-from-post-war-to-covid-19 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Theodoridis, C.; Ntounis, N.; Pal, J. How to reinvent the High Street: Evidence from the HS2020. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2017, 10, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Celińska-Janowicz, D. Resilience of the High Street and Its Public Space. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PelyoyhQq7A (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Warszawskie Ulice Handlowe w Czasie Pandemii, III kw 2020 r. Available online: https://www.colliers.com/pl-pl/research/warszawskie-ulice-handlowe (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Ulice Handlowe Wracają do Łask? Available online: https://www.wiadomoscihandlowe.pl/artykul/ulice-handlowe-wracaja-do-lask (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Gastronomia Może Przenieść Się z Centrów Handlowych na Ulice Handlowe. Available online: https://www.wiadomoscihandlowe.pl/artykul/gastronomia-moze-przeniesc-sie-z-centrow-handlowych-na-ulice-handlowe (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Czy Ulice Handlowe Mają Szansę Stać Się Alternatywą Dla Centrów? Property News. Available online: https://www.propertynews.pl/centra-handlowe/czy-ulice-handlowe-maja-szanse-stac-sie-alternatywa-dla-centrow,88487.html (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Colliers International. ExCEEding Borders. CEE-17 Retail in Times of the Pandemic, 2020/21. Available online: https://www.colliers.com/pl-pl/research/exceeding-borders-retail-2020 (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Dun & Bradstreet Company in: Bisnode Polska. Rozwój E-Commerce Szansą na Przetrwanie Polskiego Handlu. Available online: https://www.bisnode.pl/wiedza/newsy-artykuly/ecommerce-szansa-na-przetrwanie/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Baran, J.; Jankowska, A. Preferencje polskich konsumentów dotyczące zakupów internetowych odzieży. Probl. Transp. Logistyki 2017, 3, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Przenieś Swoją Firmę do Internetu—Zarabiaj na e-handlu. 20 April 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/przenies-swoja-firme-do-internetu--zarabiaj-na-e-handlu (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- PNB Paribas Real Estate, PRCH. Ulice Handlowe: Analiza, Strategia, Potencjał. Perspektywy Rozwoju Ulic Handlowych w 8 Największych Miastach w Polsce. Available online: https://swresearch.pl/raporty/ulice-handlowe-analiza-strategia-potencjal (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Jedrak, D.; Michnikowska, K. Sektor Handlowy Wciąż Przyciąga Deweloperów. Available online: https://www.colliers.com/pl-pl/news/sektor-handlowy-wciaz-przyciaga-deweloperow (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Rośnie Konkurencja Między Centrami Handlowymi. 30 November 2019. Available online: https://wgospodarce.pl/informacje/71580-rosnie-konkurencja-miedzy-centrami-handlowymi (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Dziewit, D. Przeliczeni. Tajemnice Galerii Handlowych; Wydawnictwo Videograf: Mikołów, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ustawa z Dnia 10 Stycznia 2018 r. o Ograniczeniu Handlu w Niedziele i Święta Oraz w Niektóre Inne Dni. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180000305 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Skutki Zakazu Handlu w Niedzielę dla Centrów Handlowych i Całej Branży. Available online: https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:GS7H9e0-OkQJ:https://prch.org.pl/pl/baza-wiedzy/104-handel-w-niedzele/124-raport-pwc-analiza-skutkow-wprowadzenia-zakazu-handlu-w-niedziele+&cd=2&hl=pl&ct=clnk&gl=pl (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Związek Przedsiębiorców i Pracodawców. Gospodarcze Skutki Ograniczenia Handlu w Niedziele—Realizacja Czarnego Scenariusza; Związek Przedsiębiorców i Pracodawców: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dębkowska, K.; Kłosiewicz-Górecka, U.; Szymańska, A.; Ważniewski, P.; Zybertowicz, K. Polskie Miasta w Czasach Pandemii; Polish Economic Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Covid 19 in an Urban World—UN Chief. “Pandemia COVID-19 w Miastach” Sekretarz Generalny ONZ (un.org.pl). Available online: http://www.unic.un.org.pl/oionz/covid-19-w-miastach/3364 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).