Health-Related Crises in Tourism Destination Management: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1: What types of health crises are covered in the reviewed studies, and what is their geographical scope?

- RQ2: How has tourism research evolved on health-related crises?

- RQ3: What are the keywords associated with health-related crises in tourism? And what are their implications?

- RQ4: What are the most influential publications, journals and authors in this research domain?

- RQ5: What are the impacts and consequences of health-related crises on tourism?

- RQ6: What are the strategies for tourism crisis management put forward in the reviewed studies?

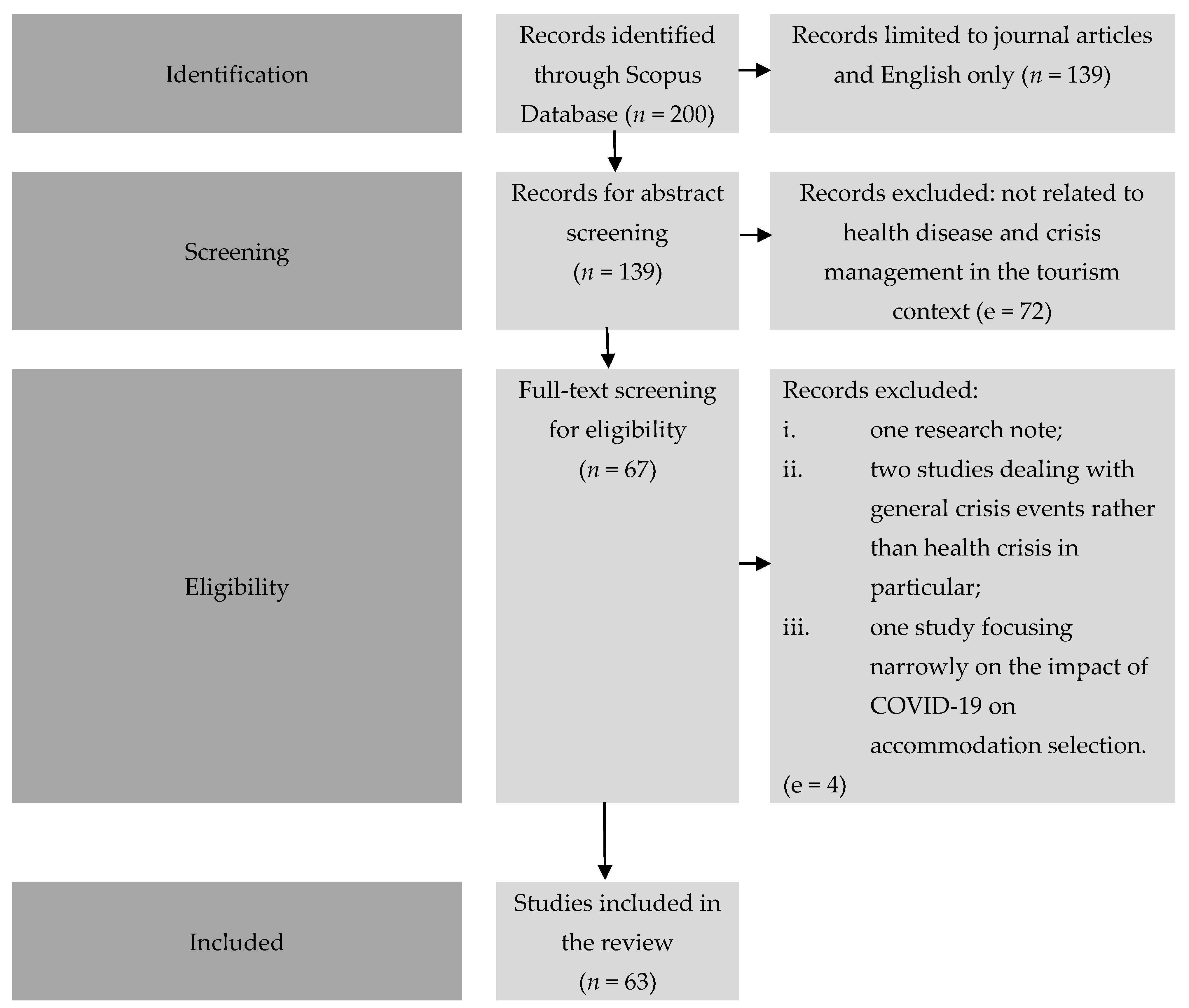

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Keyword Identification

2.2. Electronic Database Identification and Search

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Screening

2.5. Bibliometric Analysis

2.6. The Application of VOSviewer for Bibliometric Analysis

2.7. The Application of Network Theory Measures: EigenCentrality and PageRank

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Content Analysis

3.2.1. Impact on Tourism Industry

3.2.2. Impact on Tourism Demand

3.2.3. Impact on Tourist Behaviour

3.3. Bibliometric Analysis via VOSviewer

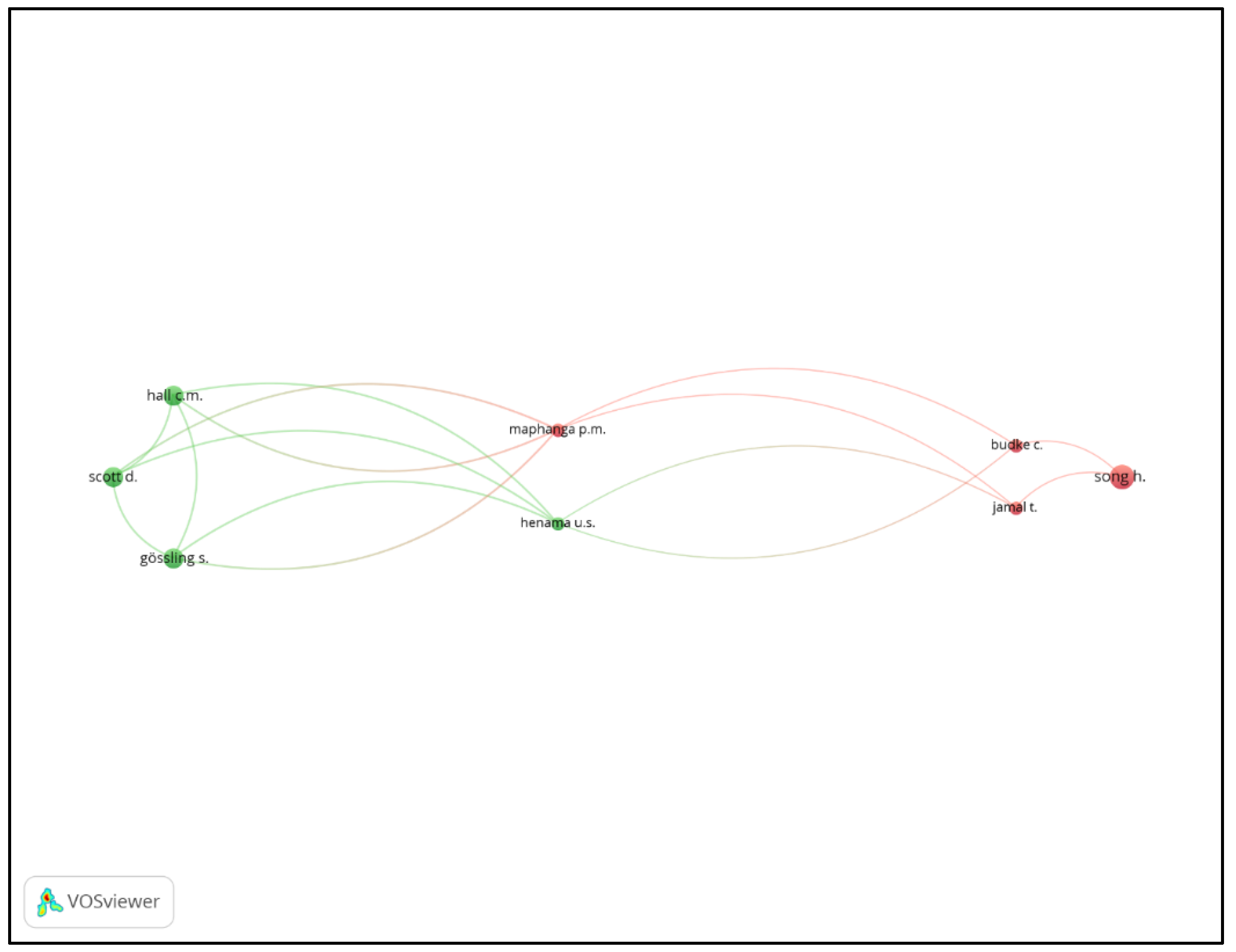

3.3.1. Co-Authorship Analysis

3.3.2. Occurrence of Author Keyword Analysis

3.3.3. Co-Occurrence of Keyword Analysis

3.3.4. Citation Analysis

3.3.5. Co-Citation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: What Types of Health Crises Are Covered in the Reviewed Studies, and What Is Their Geographical Scope?

4.2. RQ2: How Has Tourism Research on Health-Related Crises Evolved over Time?

4.3. RQ3: What Are the Keywords Associated with Health-Related Crises in Tourism? And What Is the Implication?

4.4. RQ4: What Are the Most Influential Publications, Journals and Authors in the Research Domain?

4.4.1. Influential Publications

4.4.2. Influential Journals

4.4.3. Influential Authors

4.5. RQ5: What Are the Impacts and Consequences of Health-Related Crises on Tourism?

4.6. RQ6: What Are the Strategies for Tourism Crisis Management Put Forward in the Reviewed Studies?

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| References | Year | Citations | Key Findings | Crisis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | 2020 | 419 | The authors compared the impacts of COVID-19 and previous infectious disease outbreaks on global tourism regarding the number of international tourists, including Spanish flu, SARS, swine flu, MERS and Ebola. Impacts on tourism including airlines, accommodation, MICE and sports events, restaurants and cruises. Given the vulnerability of tourism, key players in the sector such as DMOs, tourism organisations, industry representatives and large corporations should reconsider and transform the global tourism system towards sustainable development. | COVID-19 |

| [18] | 2009 | 211 | In times of crisis, travellers tend to seek travel alternatives instead of discontinuing traveling. First-time and repeat travellers showed differences in terms of perceived risks associated with disease, increase of travel costs and travel inconvenience. Repeat travellers are more knowledgeable, so they have a lower perception of disease risks than first-time travellers, yet higher perceived risks on costs and inconvenience because their past travel experience enables them to compare. | SARS and Avian (Bird) Flu |

| [19] | 2008 | 142 | It focuses on the relationship between tourism and crisis management Outbreaks adversely affects a destination’s competitiveness, and, accordingly, tourism demand. By comparing the post-crisis analysis of SARS with the pre-crisis analysis of Avian Flu, the findings suggest that preparedness, pre-crisis planning and response strategies in place will lead to effective management during a crisis. | SARS and Avian Flu |

| [20] | 2020 | 106 | Nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are measures to contain the spread of infectious disease during a pandemic, including social distancing, crowd control, travel restrictions and quarantine requirements, which have a significant impact on tourism. A pandemic may offer transformative opportunities. Yet, government interventions such as economic stimulation schemes often focus on rebuilding the business and generating jobs without considering sustainability and climate change mitigation. Resilience research suggests that the future of tourism requires a comprehensive and fundamental transformation of the global tourism system. Still, tourism recovery is often bound by the ‘business-as-usual’ mindset instead of a sustainability-oriented mindset. | COVID-19 |

| [21] | 2018 | 97 | A longitudinal study used [10]’s Rapid Situation Analysis to understand the impact of the health-related crisis on developing countries and how destinations react to the planning, response and resolution phases during a health crisis. Crisis preparation and planning enables destinations to respond to a crisis more effectively. The effect of media reporting on tourist risk perception could influence tourism demand, and the recovery strategy should consider the destination’s image and communication management. | Ebola |

| [22] | 2020 | 96 | The COVID-19 pandemic has offered a transformative opportunity to reset the tourism sector and reorient it to the public good and social and ecological justice. | COVID-19 |

| [23] | 2004 | 89 | The effect of disease outbreaks may be amplified by media coverage, images in particular. In addition, crisis planning enables destinations to respond and mitigate their impacts effectively. | General |

| [24] | 2003 | 61 | Preparation and proactive planning are essential to an effective crisis management, while the essence of crisis management is to prevent or mitigate the ‘ripple effect’ and the impacts on destinations. | Foot-and-Mouth Disease |

| [25] | 2010 | 58 | Different countries have different crisis/disaster recovery patterns in terms of tourist arrivals. The recovery process depends on two factors: the normal factor and the splitting factor. The former is concerned with the restoration to the original state (e.g., from with SARS to without SARS); the latter can generate a hysteresis effect which will affect the recovery time. The splitting factor addressed in the study is travellers’ fear and perceived risk. The recovery strategy at the macro level may consider building traveller confidence and reducing public fear through mass media campaigns; individualised marketing should be employed to reduce individual travellers’ risk perception at the micro level. | SARS |

| [26] | 2020 | 57 | The COVID-19 health crisis provides a transformative opportunity for tourism to reset and rethink how it should recover and operate. The transformation of tourism is possible, but it requires institutional innovation on tourism’s supply and demand side. | COVID-19 |

| Research Streams | Publications | Number of Publications |

|---|---|---|

| Impact on tourism industry | [9,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,63,64,81,82,85,87,92,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114] Focusing on crisis communications (12 publications): [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,115,116] | 44 |

| Impact on tourism demand | [8,42,65,93,117,118] | 6 |

| Impact on tourist behaviours | [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] Focusing on risk perception (5 publications): [59,66,67,68,69] | 13 |

| Total publications | 63 | |

References

- Woo, E.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Tourism impact and stakeholders’ quality of life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 260–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samimi, A.J.; Sadeghi, S.; Sadeghi, S. Tourism and economic growth in developing countries: P-VAR approach. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2011, 10, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pforr, C.; Hosie, P.J. Crisis management in tourism: Preparing for recovery. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.-S. Safety, security and peace tourism: The case of the DMZ area. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2005, 10, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Crisis events in tourism: Subjects of crisis in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism and COVID-19—Unprecedented Economic Impacts|UNWTO. 2020. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/tourism-and-covid-19-unprecedented-economic-impacts (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- António, N.; Rita, P.; Saraiva, P. COVID-19: Worldwide Profiles during the First 250 Days. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, P. COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B. Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevas, A.; Arendell, B. A strategic framework for terrorism prevention and mitigation in tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1560–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W. Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, A.; Singh, R. Managing Disaster and Crisis in Tourism: A Critique of Research and a fresh Research Agenda. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- António, N.; Rita, P. COVID 19: The catalyst for digital transformation in the hospitality industry? COVID-19: O catalisador para a transformação digital no sector hoteleiro? Tour. Manag. Stud. 2021, 17, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinelli, S.; Moro, S.; Rita, P. Air-travelers’ concerns emerging from online comments during the COVID-19 outbreak. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Xie, C.; Morrison, A.M. Tourism Crises and Impacts on Destinations: A Systematic Review of the Tourism and Hospitality Literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliperti, G.; Sandholz, S.; Hagenlocher, M.; Rizzi, F.; Frey, M.; Garschagen, M. Tourism, Crisis, Disaster: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevão, C.; Costa, C. Natural disaster management in tourist destinations: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 2502. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Law, R.; Zhang, M. Review of research on tourism-related diseases. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 26, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele UK Keele Univ. 2004, 33, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Altman, D.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. Scaling Up the Capacity of Nursing and Midwifery Services to Contribute to the Achievement of the MDGs: Report of the 11th Meeting, Geneva, 17–18 March 2008; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A. The severe acute respiratory syndrome: Impact on travel and tourism. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2006, 4, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meline, T. Selecting studies for systemic review: Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Contemp. Issues Commun. Sci. Disord. 2006, 33, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Tang, Y.; Hao, T. A bibliometric analysis of event detection in social media. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 43, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leydesdorff, L.; Rafols, I. Interactive overlays: A new method for generating global journal maps from Web-of-Science data. J. Informetr. 2012, 6, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, J.; Tallia, A.; Crosson, J.C.; Orzano, A.J.; Stroebel, C.; DiCicco-Bloom, B.; O’Malley, D.; Shaw, E.; Crabtree, B. Social network analysis as an analytic tool for interaction patterns in primary care practices. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastian, M.; Heymann, S.; Jacomy, M. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In Proceedings of the Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bonacich, P. Factoring and weighting approaches to status scores and clique identification. J. Math. Sociol. 1972, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Page, L. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual web search engine. Comput. Netw. ISDN Syst. 1998, 30, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E.; Ding, Y. Discovering author impact: A PageRank perspective. Inf. Process. Manag. 2011, 47, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bibi, F.; Khan, H.U.; Iqbal, T.; Farooq, M.; Mehmood, I.; Nam, Y. Ranking authors in an academic network using social network measures. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, Y.; Yan, E.; Frazho, A.; Caverlee, J. PageRank for ranking authors in co-citation networks. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2229–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, E.; Ding, Y. Applying centrality measures to impact analysis: A coauthorship network analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2009, 60, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khan, G.F.; Wood, J. Information technology management domain: Emerging themes and keyword analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Mao, J.; Lu, K. Ranking themes on co-word networks: Exploring the relationships among different metrics. Inf. Process. Manag. 2018, 54, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.K.C.; Mark, C.K.M.; Yeung, M.P.S.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Graham, C.A. The role of the hotel industry in the response to emerging epidemics: A case study of SARS in 2003 and H1N1 swine flu in 2009 in Hong Kong. Global. Health 2018, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maphanga, P.M.M.; Henama, U.S.S. The tourism impact of ebola in Africa: Lessons on crisis management. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Memish, Z.A.; Cotten, M.; Meyer, B.; Watson, S.J.; Alsahafi, A.J.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Corman, V.M.; Sieberg, A.; Makhdoom, H.Q.; Assiri, A. Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, D.; Luo, Q.; Ritchie, B.W. Afraid to travel after COVID-19? Self-protection, coping and resilience against pandemic ‘travel fear’. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio-Martin, J.-L.; Sinclair, M.T.T.; Yeoman, I. Quantifying the effects of tourism crises: An application to Scotland. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2006, 19, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisby, E. Communicating in a crisis: The British Tourist Authority’s responses to the foot-and-mouth outbreak and 11th September, 2001. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C.C. Managing a health-related crisis: SARS in Singapore. J. Vacat. Mark. 2004, 10, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, P. Marketing London in a difficult climate. J. Vacat. Mark. 2003, 9, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, W.; Anderson, A.R.R. Small tourist firms in rural areas: Agility, vulnerability and survival in the face of crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2004, 10, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, W.; Anderson, A.R.R. The impacts of foot and mouth disease on a peripheral tourism area: The role and effect of crisis management. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2006, 19, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.W.; Dorrell, H.; Miller, D.; Miller, G.A.A. Crisis communication and recovery for the tourism industry: Lessons from the 2001 foot and mouth disease outbreak in the United Kingdom. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schroeder, A.; Pennington-Gray, L. The Role of Social Media in International Tourist’s Decision Making. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. Communicating tourism crises through destination websites. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 23, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoman, I.; Lennon, J.J.J.; Black, L. Foot-and-mouth disease: A scenario of reoccurrence for Scotland’s tourism industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re)generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, M. Reconstructing tourism in the Caribbean: Connecting pandemic recovery, climate resilience and sustainable tourism through mobility justice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 14361–14449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Dillette, A.; Alderman, D.H.H. “We can’t return to normal”: Committing to tourism equity in the post-pandemic age. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P. Reset redux: Possible evolutionary pathways towards the transformation of tourism in a COVID-19 world. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.-L.; Tariq, B.; Radic, A.; Park, S.-H. The post-coronavirus world in the international tourism industry: Application of the theory of planned behavior to safer destination choices in the case of us outbound tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ioannides, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for escaping the unsustainable global tourism path. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, Y.; Karkour, S.; Ichisugi, Y.; Itsubo, N. Evaluation of the economic, environmental, and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the japanese tourism industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Thompson, M.; Pabel, A. Lessons from COVID-19 can prepare global tourism for the economic transformation needed to combat climate change. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Roldán, L.; Canalejo, A.M.C.M.C.; Berbel-Pineda, J.M.M.; Palacios-Florencio, B. Sustainable tourism as a source of healthy tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, H. The impact of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus on inbound tourism in South Korea toward sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1117–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, A.M.M.; Pichierri, M. Effects of socio-demographics, sense of control, and uncertainty avoidability on post-COVID-19 vacation intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2755–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N.N.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.L.; Zeng, X.; Morrison, A.M.A.M.; Liang, H.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.A. A risk perception scale for travel to a crisis epicentre: Visiting Wuhan after COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Couto, G.; Pimentel, P.; Sousa, A.; Carvalho, C.; Batista, M.D.G. How an infectious disease could influence the development of a region: The evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak over the tourism intentions in azores archipelago. Duzce Med. J. 2021, 23, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, G.; Castanho, R.A.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á.; Santos, C. The impacts of COVID-19 crisis over the tourism expectations of the Azores Archipelago residents. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.; Kozak, M.; Wen, J. Seeing the invisible hand: Underlying effects of COVID-19 on tourists’ behavioral patterns. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Luna, L.; Robina-Ramírez, R.; Sánchez, M.S.-O.; Castro-Serrano, J. Tourism and sustainability in times of covid-19: The case of Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.T.R.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodway-Dyer, S.; Shaw, G. The effects of the foot-and-mouth outbreak on visitor behaviour: The case of dartmoor national park, south-west England. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A.; Krasnodębski, A. Respondents’ involvement in tourist activities at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.-A.; Kim, K.-W.; Kwon, H.-J. Big data analysis of Korean travelers’ behavior in the post-COVID-19 era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, M.; Mashud, M.; Ida, R. Usage of social media during the pandemic: Seeking support and awareness about COVID-19 through social media platforms. J. Public Aff. 2020, 20, e2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xiao, L. Selecting publication keywords for domain analysis in bibliometrics: A comparison of three methods. J. Informetr. 2016, 10, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S. Practical applications of do-it-yourself citation analysis. Ser. Libr. 2013, 64, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Budke, C. Tourism in a world with pandemics: Local-global responsibility and action. J. Tour. Futur. 2020, 6, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Chon, K. The over-reaction to SARS and the collapse of Asian tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, C.-K.; Ding, C.G.G.; Lee, H.-Y. Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on a catastrophe theory. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsouyanni, K. Collaborative research: Accomplishments & potential. Environ. Health 2008, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, M.; Gussing Burgess, L.; Jones, A.; Ritchie, B.W.W. ‘No Ebola…still doomed’—The Ebola-induced tourism crisis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.H.; Xuan, H.N. INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC INTEGRATION TO DEVELOP SUSTAINABLE TOURISM IN SAPA, Vietnam. Psychol. Educ. J. 2021, 58, 7160–7171. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Krieger, J. Tourism crisis management: Can the Extended Parallel Process Model be used to understand crisis responses in the cruise industry? Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCImago. Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management Journal Rankings. 2019. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=1409 (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Wen, J.; Wang, W.; Kozak, M.; Liu, X.; Hou, H. Many brains are better than one: The importance of interdisciplinary studies on COVID-19 in and beyond tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 46, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- António, N.; Rita, P. March 2020: 31 days that will reshape tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2768–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-I.; Chen, C.-C.; Tseng, W.-C.; Ju, L.-F.; Huang, B.-W. Assessing impacts of SARS and Avian Flu on international tourism demand to Asia. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A.A.; Ritchie, B.W.W. A farming crisis or a tourism disaster? An analysis of the foot and mouth disease in the UK. Curr. Issues Tour. 2003, 6, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Škare, M.; Soriano, D.R.R.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Impact of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.; Ferguson, M. Biting the hand that feeds: The marginalisation of tourism and leisure industry providers in times of agricultural crisis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2005, 8, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.M.M. COVID-19 impacts and recovery strategies: The case of the hospitality industry in Spain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.; Ferguson, M. Recovering from crisis. Strategic alternatives for leisure and tourism providers based within a rural economy. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2005, 18, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Patuleia, M.; Silva, R.; Estêvão, J.; González-Rodríguez, M.R. Post-pandemic recovery strategies: Revitalizing lifestyle entrepreneurship. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.K.K.; Nafi, S.M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on tourism: Recovery proposal for future tourism. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2021, 33, 1486–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ale Ebrahim, N. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Song, M. Science mapping tools and applications. In Representing Scientific Knowledge; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 57–137. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. J. Informetr. 2014, 8, 802–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bautista, H.; Valeeva, G.; Danilevich, V.; Zinovyeva, A. A Development strategy for the revival of tourist hotspots following the covid-19 pandemic. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 2020, 9, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Peng, L.; Yin, X.; Jing, B.; Yang, J.; Cong, G.; Li, G. A policy category analysis model for tourism promotion in china during the covid-19 pandemic based on data mining and binary regression. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 3211–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coles, T. A local reading of a global disaster: Some lessons on tourism management from an anus horribilis in South West England. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.J.J.; Ryu, H.B.B. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), traveler behaviors, and international tourism businesses: Impact of the corporate social responsibility (csr), knowledge, psychological distress, attitude, and ascribed responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.W.; Smith, W.W.W. International Travel and Coronavirus: A Very Early USA-based Study. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marome, W.; Shaw, R. COVID-19 response in Thailand and its implications on future preparedness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; Pinto, J.; Liu, M. City resilience and recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. Cities 2021, 112, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda Lopez, R.; Lopez-Felipe, T.; Navajas-Romero, V.; Menor-Campos, A. Lessons from the First Wave of COVID-19. What Security Measures Do Women and Men Require from the Hotel Industry to Protect against the Pandemic? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L.L.L. Cuba’s response to COVID-19: Lessons for the future. J. Tour. Futur. 2021, 7, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Wen, L.; Liu, C. Forecasting tourism recovery amid COVID-19. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Li, Z. A content analysis of Chinese news coverage on COVID-19 and tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Kim, J.; Pennington-Gray, L. Social media information and peer-to-peer accommodation during an infectious disease outbreak. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinth, B.; Ranasinghe, R. Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on tourism in poland in march 2020. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Li, K.X.X. Impact of unexpected events on inbound tourism demand modeling: Evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Crisis (Disease) | Number of Papers | Total Citations | Total Citations per Year Since Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | 4 | 678 | 678 |

| SARS | 3 * | 269 | 34 |

| Ebola | 1 | 97 | 32 |

| Avian flu | 2 * | 353 | 29 |

| General health diseases | 1 | 89 | 5 |

| Foot-and-Mouth Disease | 1 | 61 | 3 |

| Rank | Authors | EigenCentrality | Authors | PageRank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Castanho R. A. | 1 | Song H. | 0.015329 |

| 2 | Couto G. | 1 | Ritchie B. W. | 0.011308 |

| 3 | Carvalho C. | 1 | Han H. | 0.011254 |

| 4 | Pimentel P. | 1 | Yeoman I. | 0.010860 |

| 5 | Chen T. | 0.81482 | Li Z. | 0.010736 |

| 6 | Cong G. | 0.81482 | Pennington-Gray L. | 0.009982 |

| 7 | Jing B. | 0.81482 | Castanho R. A. | 0.007807 |

| 8 | Li G. | 0.81482 | Couto G. | 0.007807 |

| 9 | Peng L. | 0.81482 | Carvalho C. | 0.007807 |

| 10 | Yang J. | 0.81482 | Pimentel P. | 0.007807 |

| Country | Documents | Citations | Citations per Paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 17 | 1080 | 63.53 * |

| United States | 10 | 356 | 35.60 |

| Australia | 7 | 364 | 52.00 |

| China | 6 | 87 | 14.50 |

| Spain | 6 | 11 | 1.83 |

| Canada | 5 | 594 | 118.80 * |

| Poland | 5 | 34 | 6.80 |

| South Korea | 5 | 30 | 6.00 |

| Portugal | 4 | 10 | 2.50 |

| Croatia | 3 | 32 | 10.67 |

| Sweden | 3 | 577 | 192.33 * |

| Rank | Keywords | EigenCentrality | Keywords | PageRank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | COVID-19 | 1 | COVID-19 | 0.070836 |

| 2 | Tourism | 0.445909 | Pandemic | 0.025553 |

| 3 | Pandemic | 0.440224 | Tourism | 0.025537 |

| 4 | Crisis management | 0.318418 | Crisis management | 0.020377 |

| 5 | Sustainable tourism | 0.280801 | Foot-and-mouth disease | 0.015369 |

| 6 | Crisis | 0.247390 | Sustainable tourism | 0.014768 |

| 7 | Resilience | 0.219670 | Crisis | 0.013895 |

| 8 | Sustainability | 0.176509 | SARS | 0.009927 |

| 9 | Transformation | 0.167250 | Perceived risk | 0.009071 |

| 10 | Domestic tourism | 0.166604 | Tourism industry | 0.007572 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vong, C.; Rita, P.; António, N. Health-Related Crises in Tourism Destination Management: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413738

Vong C, Rita P, António N. Health-Related Crises in Tourism Destination Management: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413738

Chicago/Turabian StyleVong, Celeste, Paulo Rita, and Nuno António. 2021. "Health-Related Crises in Tourism Destination Management: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13738. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413738