Impact of the COVID-19 on the Destination Choices of Hungarian Tourists: A Comparative Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Background

Summary of the Results of International Research on New Trends

3. Research Methodology

- -

- since decision trees are unstable, small variations in training data can significantly change the structure of the decision tree;

- -

- each decision depends on the data available at each node, so it does not exploit the characteristics of all data points, which can lead to poor classification performance;

- -

- induction tree computations can become very complex and lengthy, especially when many values are uncertain or when multiple outputs are linked.

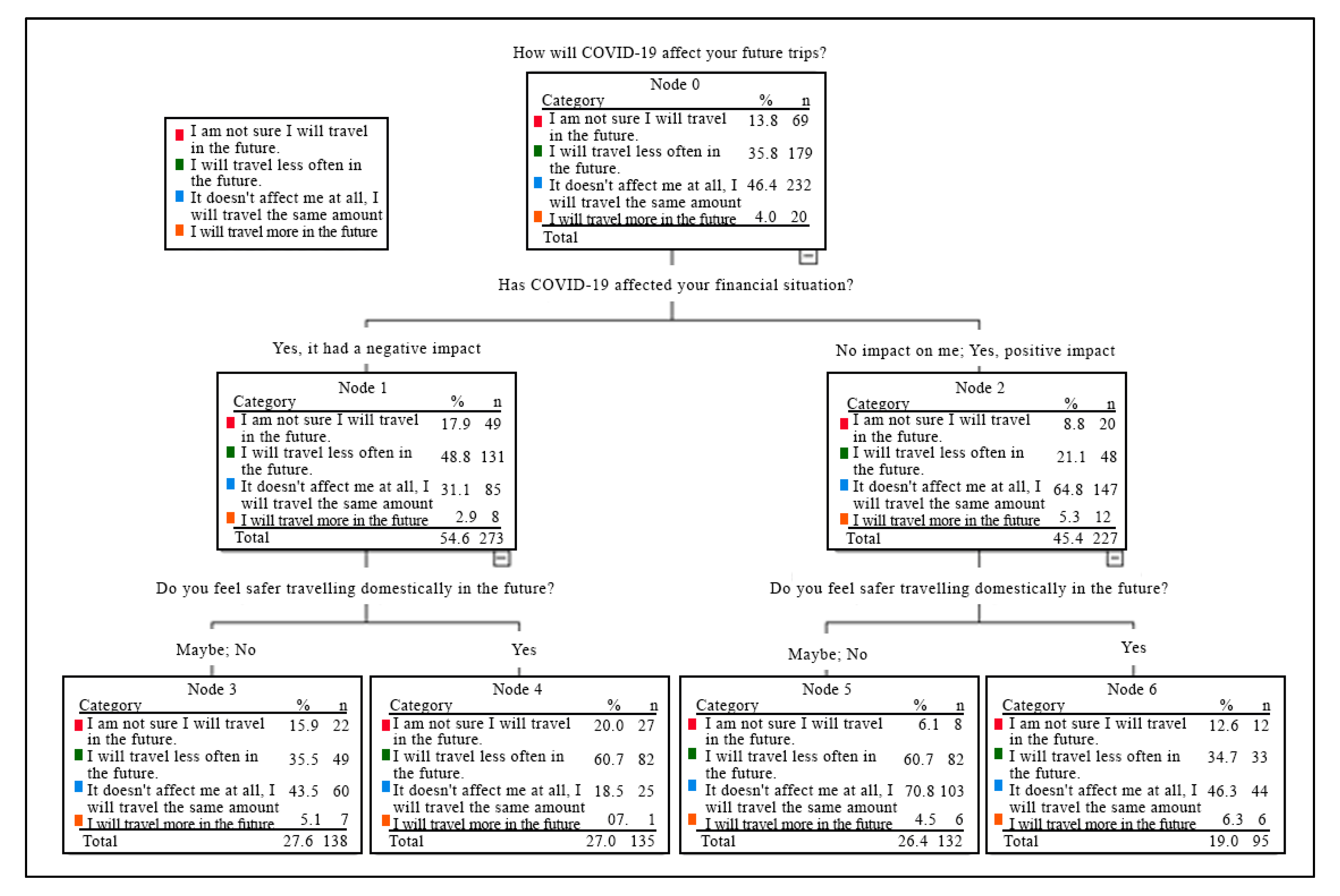

4. Presentation of the Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

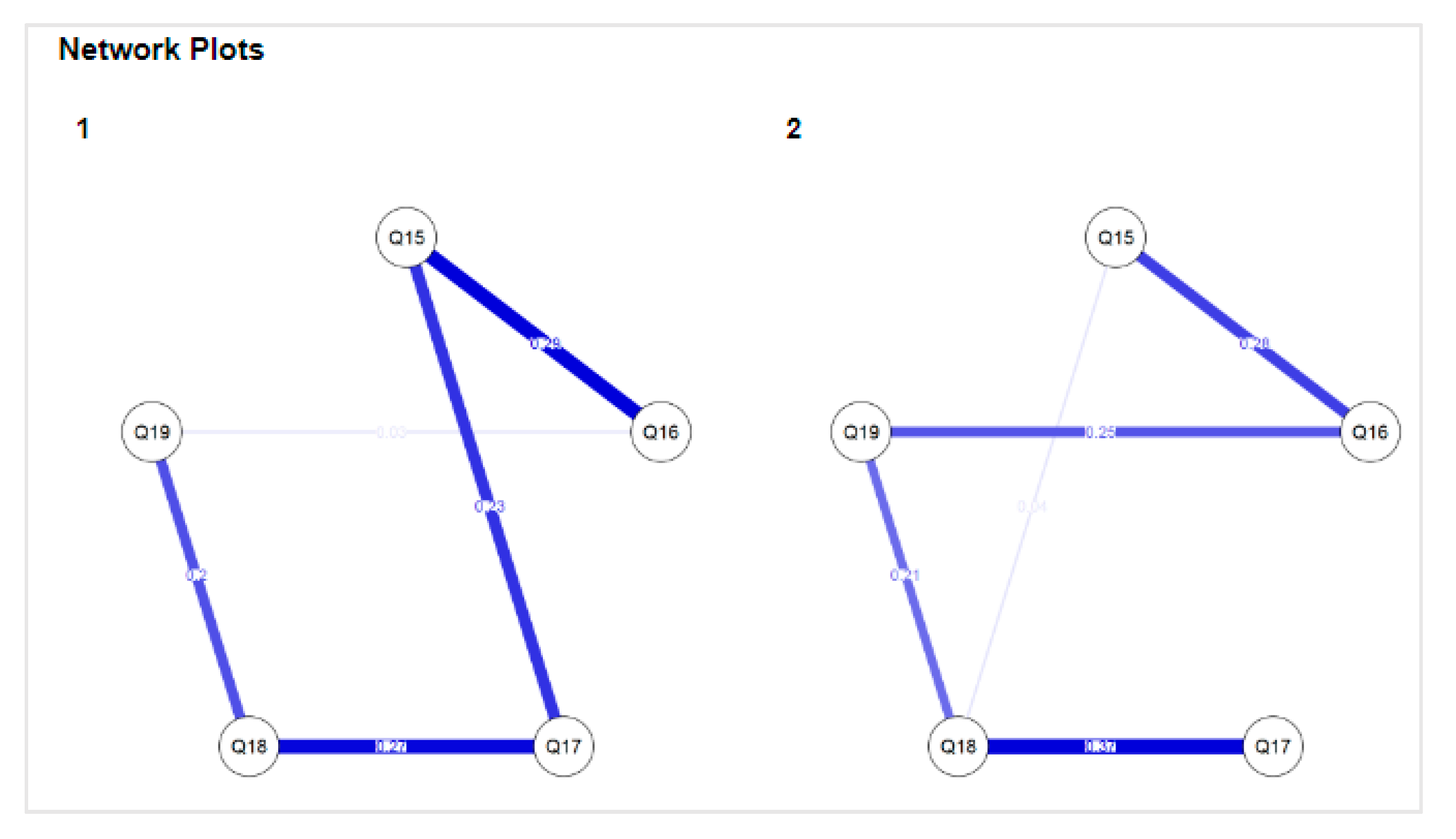

4.2. Changes in Respondents’ Destination Choices

- Intended trips to a domestic destination (within 150 km of home): the most dominant influencing factor is previous experiences related to the destination (G2 = 719.18), but also the experience of a new culture (G2 = 570.50), safety (G2 = 423.46) and proximity to nature (G2 = 413.97). Lower explanatory power is attributed to the distance traveled (G2 = 377.36), support for the recovery of domestic tourism (G2 = 282.35) and finally the cost of the trip (G2 = 200.55). Health risks, epidemiological standards, the expected number of tourists and active recreation have a lower explanatory power and are not considered to be a factor in the decision for this planned distance.

- Intended trips to the home country (more than 150 km from the place of residence): the factors of active recreation (e.g., nature walk, sports activity) (G2 = 1390.60) and travel distance (G2 = 1081.19) have a high explanatory power. Health risks (G2 = 698.26), previous experiences related to the destination (G2 = 361.45) and, to a much lesser extent, exposure to a new culture (G2 = 84.83) are factors that are significantly lower in importance but still influence the decision, based on the responses from the sample. The explanatory power of the other factors assessed is 0.

- To a neighboring country (within 150 km of home): the explanatory power of this category, which can also be described as short trips abroad, is significantly lower, although the number of mentions was also lower in the sample. Nevertheless, the factors that influenced the decision were found. The main factors were closeness to nature (G2 = 251.83), epidemiological regulations (G2 = 121.45), experience of a new culture (G2 = 99.41), safety (G2 = 85.05), expected number of tourists (G2 = 71.94), active recreation (e.g., nature walks, sports activities) (G2 = 64.35), previous experiences related to travel (G2 = 46.61) and travel distance (G2 = 35.73).

- To a neighboring country (more than 150 km from the place of residence): learning about a new culture (G2 = 709.344), health risks (G2 = 533.14), expected number of tourists (G2 = 245.39), proximity to nature (G2 = 89.42) and to a lesser extent the cost of the trip (G2 = 6.91) were considered as important decision factors for longer trips.

- To a non-neighboring European country: the decision factors for traveling further afield include the opportunity to experience a new culture (G2 = 961.622), health risks (G2 = 234.76), the cost of traveling (G2 = 132.71) and proximity to nature (G2 = 103.80).

- To a non-European country: this factor also had a lower mention rate, but it is clear that, despite the value levels, the proportion of people who mentioned experiencing a new culture is higher than the other influencing factors (G2 = 236.71). Other influencing factors include previous experiences related to travel (G2 = 67.59), safety (G2 = 65.21), proximity to nature (G2 = 43.4), distance traveled (G2 = 29.20) and active recreation (e.g., nature walks, sports activities) (G2 = 23.29).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- UNWTO. Inclusive Recovery Guide—Sociocultural Impacts of COVID-Issue 2: Cultural Tourism. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284422579 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Consumer Survey Finds 70% of Travelers Plan to Holiday in. Available online: https://wttc.org/News-Article/Consumer-Survey-Finds-70-Percent-of-Travelers-Plan-to-Holiday-in-2021 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- State Audit Office. Elemzés: A Turizmus Helyzete—A Járvány Előtt És Alatt. (Analysis: The State of Tourism—Before and During the Epidemic). Available online: https://www.asz.hu/storage/files/files/elemzesek/2021/turizmus_jarvany20210325.pdf?ctid=1259 (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- European Travel Commission. European Tourism: Trends & Prospects. Quarterly Report (Q2/2021). Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/uploads/2021/07/ETC_Quarterly_Report-Q2_2021.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- UNWTO. Vaccines and Reopen Borders Driving Tourism’s Recovery. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/taxonomy/term/347 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- UNWTO. UNWTO Highlights Potential of Domestic Tourism to Help Drive Economic Recovery in Destinations Worldwide. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/unwto-highlights-potential-of-domestic-tourism-to-help-drive-economic-recovery-in-destinations-worldwide (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Tourism Online. Minden Idők Legjobb Nyara a Belföldi Turizmusban. (Best Summer Ever for Domestic Tourism). Available online: http://turizmusonline.hu/belfold/cikk/minden_idok_legjobb_nyara_a_belfoldi_turizmusban (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Eichelberger, S.; Heigl, M.; Peters, M.; Pikkemaat, B. Exploring the Role of Tourists: Responsible Behavior Triggered by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booking.com. Sustainable Travel Report. Available online: https://news.booking.com/download/1038851/booking.comsustainabletravelreport2021.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Sung, Y.-A.; Kim, K.-W.; Kwon, H.-J. Big Data Analysis of Korean Travelers’ Behavior in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Sustainability 2021, 13, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodbod, A.; Hommes, C.; Huber, S.J.; Salle, I. The COVID-19 consumption game-changer: Evidence from a large-scale multi-country survey. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 140, 103953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Insight Series—COVID-19 and Tourism. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-03/UNWTO%20Insights%20Series_UNWTO%20presentation.pdf?CMpUEdkrHiVf2xuIzZGxWUIBDK7I9UPb (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- AirBnB. Airbnb Report on Travel & Living. Available online: https://news.airbnb.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2021/05/Airbnb-Report-on-Travel-Living.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Booking.com. The Five Emerging Trip Types of. Available online: https://globalnews.booking.com/the-five-emerging-trip-types-of-2021/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Miles Partnership, Longwoods International. Travel Sentiment Study Wave. Available online: https://ss-usa.s3.amazonaws.com/c/308483931/media/1561618020d6097b345671883383636/Coronavirus%20Survey%20Wave%2049.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- European Travel Commission. Monitoring Sentiment for Domestic and Intra-European Travel—Wave. Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/monitoring-sentiment-for-domestic-and-intra-european-travel-wave-9/ (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Pan, K.; Yue, X.-G. Multidimensional effect of Covid-19 on the economy: Evidence from survey data. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2021, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A.; Krasnodębski, A. Respondents’ Involvement in Tourist Activities at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitano, A.; Fazio, M.; Schirripa Spagnolo, F.; Karanasios, N. COVID-19 Impact on the Tourism Industry: Short Holidays within National Borders. Symph. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2021, 2, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacé-Molinero, T.; Fernández-Muñoz, J.-J.; Orea-Giner, A.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Understanding the new post-COVID-19 risk scenario: Outlooks and challenges for a new era of tourism. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Bhati, A.; Mohammadi, Z.; Agarwal, M.; Kamble, Z.; Donough-Tan, G. Motivating or manipulating: The influence of health-protective behaviour and media engagement on post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.-L.; Tariq, B.; Radic, A.; Park, S.-H. The Post-Coronavirus World in the International Tourism Industry: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Safer Destination Choices in the Case of US Outbound Tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. Gender as moderator of the influence of tourists’ risk perception on destination image and visit intentions. Tour. Rev. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B.; Mirehie, M.; Cecil, A. Are female business travelers willing to travel during COVID-19? An exploratory study. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terziyska, I.; Dogramadjieva, E. Should I stay or should I go? Global COVID-19 pandemic influence on travel intentions of Bulgarian residents. SHS Web Conf. 2021, 92, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszka, P.; Huszka, P.B. Vásárlási-utazási motivációk változása a COVID járvány idején. In “Változó Világ, Változó Turizmus” XI. Nemzetközi Turizmus Konferencia; Alberth-Tóth, A., Happ, É., Printz-Markó, E., Eds.; Széchenyi István University: Győr, Hungary, 2021; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Raffay, Z.A. COVID-19 Járvány Hatása a Turisták Fogyasztói Magatartásának Változására. In The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Change of Consumer Behaviour of Tourists; University of Pécs, Faculty of Economics, Institute of Marketing and Tourism: Pécs, Hungary, 2021; Available online: https://ktk.pte.hu/sites/ktk.pte.hu/files/images/008_A%20COVID-19%20jarvany%20hatasa%20a%20turistak%20fogyasztoi%20magatartasanak%20valtozasara.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- Persson-Fischer, U.; Liu, S. The Impact of a Global Crisis on Areas and Topics of Tourism Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomski, P. COVID-19: From temporary de-globalisation to a re-discovery of tourism? Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The End of Global Travel as We Know It: An Opportunity for Sustainable Tourism. The Conversation. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-end-of-global-travel-as-we-know-it-an-opportunity-for-sustainable-tourism-133783 (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Vărzaru, A.A.; Bocean, C.G.; Cazacu, M. Rethinking Tourism Industry in Pandemic COVID-19 Period. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J.; Baker, C.; Fyall, A. COVID-19 and Tourism: Analyzing the Effects of COVID-19 Statistics and Media Coverage on Attitudes toward Tourism. Forecasting 2021, 3, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peponi, A.; Morgado, P.; Trindade, J. Combining Artificial Neural Networks and GIS Fundamentals for Coastal Erosion Prediction Modeling. Sustainability 2019, 11, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Sarkar, D.; Roy, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Goel, V.; Almatrafi, E. Application of New Artificial Neural Network to Predict Heat Transfer and Thermal Performance of a Solar Air-Heater Tube. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claveria, O.; Monte, E.; Torra, S. Tourism demand forecasting with neural network models: Different ways of treating information. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Wu, J.-Z.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Alahmadi, A.; Ansari, M.F.; Ryan, M.J. Attention-Based STL-BiLSTM Network to Forecast Tourist Arrival. Processes 2021, 9, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, G.; Mamier, M.; Vogt, N.; Mache, R.; Huebner, S.; Doering, K.-U.; Hermann, T.; Soyez, M.; Schmalzl, T.; Sommer, A.; et al. SNNS Stuttgart Neural Network Simulator User Manual, Version 4.2 IPVR; University of Stuttgart and WSI, University of Tübingen: Tübingen, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenfeld, N. The Nature of Mathematical Modelling; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rossel, R.A.V.; Behrens, T. Using data mining to model and interpret soil diffuse reflectance spectra. Geoderma 2010, 158, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porwal, A.; Carranza, E.J.M.; Hale, M. Artificial neural networks for mineral-potential mapping: A case study from Aravalli Province, Western India. Nat. Resour. Res. 2003, 12, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beucher, A.; Møller, A.B.; Greve, M. Artificial neural networks and decision tree classification for predicting soil drainage classes in Denmark. Geoderma 2017, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeir, C.N.; Benítez Sánchez, J.M. Neural Networks in R Using the Stuttgart Neural Network Simulator: RSNNS. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 7, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Classification: Basic concepts, decision trees, and model evaluation. Introd. Data Min. 2006, 1, 145–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsimas, D.; Dunn, J. Optimal classification trees. Mach. Learn. 2017, 106, 1039–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windeatt, T.; Ardeshir, G. An empirical comparison of pruning methods for ensemble classifiers. In International Symposium on Intelligent Data Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 208–217. [Google Scholar]

- Boundless. Quantitative and Analytical Management Tools. Available online: http://kolibri.teacherinabox.org.au/modules/en-boundless/www.boundless.com/management/textbooks/boundless-management-textbook/organizational-theory-3/modern-thinking-31/quantitative-and-analytical-management-tools-175-8291/index.html (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Scikit. Scikit Learn. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/_downloads/scikit-learn-docs.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Magyar, Z.; Sulyok, K. Az ökoturizmus helyzete Magyarországon. (The state of ecotourism in Hungary). Tur. Bull. 2014, 16, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccato, R.; Rossi, R.; Gastaldi, M. Travel Demand Prediction during COVID-19 Pandemic: Educational and Working Trips at the University of Padova. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungarian National Parks. Márkanév Erősíti a Nemzeti Parkok Ökoturisztikai Kínálatát. (Branding Strengthens the Ecotourism Offer of National Parks). Available online: http://magyarnemzetiparkok.hu/okoturisztikai-kinalat-kampany/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- The Hungarian Tourism Agency. Turizmus 2. Available online: https://mtu.gov.hu/documents/prod/NTS2030_Turizmus2.0-Strategia.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2021).

| Age | Number of Persons | % of Respondents |

|---|---|---|

| 15–18 years | 184 | 37% |

| 19–35 years | 30 | 6% |

| 36–50 years | 90 | 18% |

| 51–65 years | 110 | 22% |

| ≥66 years | 86 | 17% |

| Household Size | Number of Persons | % of Respondents |

| 1 | 67 | 13% |

| 2 | 223 | 45% |

| 3 | 96 | 19% |

| 4 | 77 | 15% |

| ≥5 | 37 | 7% |

| Education | Number of Persons | % of Respondents |

| Secondary education | 348 | 70% |

| Primary education | 34 | 7% |

| Tertiary education | 104 | 21% |

| PhD | 14 | 3% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kupi, M.; Szemerédi, E. Impact of the COVID-19 on the Destination Choices of Hungarian Tourists: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413785

Kupi M, Szemerédi E. Impact of the COVID-19 on the Destination Choices of Hungarian Tourists: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413785

Chicago/Turabian StyleKupi, Marcell, and Eszter Szemerédi. 2021. "Impact of the COVID-19 on the Destination Choices of Hungarian Tourists: A Comparative Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413785

APA StyleKupi, M., & Szemerédi, E. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 on the Destination Choices of Hungarian Tourists: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability, 13(24), 13785. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413785