Abstract

The main objective of this paper is to explore the institutional convergence of Central and Eastern European Union member countries as a possible consequence of both the transfer of selected Western formal institutions to those countries and the adoption of acquis communautaire. This issue dates back to the beginning of the 1990s when the predominant expectation was that the successful formal institutions in Western countries would yield the same results in transition countries. In the meantime, mainly because of informal constraints, this has shown to be a misconception in most cases. The methodology used in the paper is twofold. First, by means of descriptive statistics, and using the varieties of capitalism approach, we show that, when analysing institutional quality using the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), there are two divergent groups of EU countries. The first group consists of Liberal, Nordic, and Continental countries, and the second consists of Mediterranean and CEE member states that are further divided into liberal and coordinated market economies. Second, based on the calculation of the σ- and unconditional β-convergence of governance trends in the period 1996–2019, we empirically confirm that there are also variations within the CEE countries as well as within the specific dimensions of governance.

1. Introduction

The beginning of post-socialist transformation was a period characterised by a great gap. It was considered a historic opportunity for large-scale change, yet the deficit of expertise and understanding required for such transformation was quite evident. In addition, the legacy of the socialist period was underestimated. Hence, most scholars and incumbents advocated for ready-made solutions that had previously been shown to be successful. This meant importing Western best practices that, according to their results in countries of origin, were expected to yield benefits in transitional societies as well. EU accession was perceived as another great momentum for institutional change(s) and convergence based on mutual formal institutions—the acquis communautaire. However, rapid change did not happen according to prevailing initial expectations, and diversity among countries appeared to emerge in various aspects.

For the purpose of this article, i.e., to investigate the convergence of Eastern European countries as a potential result of the transfer of Western formal institutions to those countries, the latest edition of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) dataset was used. The issue of institutional cconvergence is of high economic interest since it is positively related to real (economic) convergence, and a better understanding of institutional development is much needed in order to achieve economic convergence through institutional development [1]. Within this, while real convergence usually refers to the convergence in GNI per capita, under the term institutional convergence, we describe the convergence in institutions, i.e., in rules of the game in a society as defined by North [2]. In order to grasp the causes of revealed trends, in further steps, we calculated the coefficient of variation as a measure of dispersion for each group of countries in order to test for the sigma (σ) convergence and tested the unconditional beta (β) convergence, performing a cross-section regression analysis in the period from 1996 to 2019. It is assumed that σ-convergence is present when the coefficient of variation declines between the periods, while β-convergence occurs when the parameter β is negative and statistically significant. In performing our analysis, we rely on the literature dealing with real and institutional convergence parameters [1,3,4,5,6].

The analysis performed in this paper shows that even after the second “convergence push” (after EU accession), the trends might be considered surprising, at least in the areas under the governance umbrella. The second convergence was about resilient linkages between market coordination on one side and private property rights on the other [7]. Under Kornai’s so called affinity thesis, it is highlighted that the bureaucratic type of coordination has a natural affinity for state property, whereas market coordination has a natural affinity for private property [7,8]. In contrast, the link between market coordination and state property is weak. Thus, through employing the data on governance in our analysis, we can expect to see the somewhat divergent trajectories of the observed groups of countries.

The contribution of the paper is threefold. Firstly, this research in its broad terms captures insights into the rising heterogeneity among transitional societies [9,10,11,12,13]. Secondly, while most recent studies focus on analysing the difference between countries, classifying them into new member states, Eurozone member states, etc., our paper takes a varieties of capitalism (VoC) approach to the specific group of countries, i.e., CEECs, classifying them further by the specific type of market system. To be precise, according to the VoC approach, there are two extremes on the spectrum between pure market power and coordination of market forces. These are the liberal market economies (LME) versus the coordinated market economies (CME) [14]. The rationale for such an approach lies in the literature which highlights that despite being developed for advanced market economies, selected inputs from the VoC approach underpin the analysis of reform efforts in transition. Precisely, the starting point of VoC is that countries possess specific, historically predetermined, national institutional equilibria that consist of interconnected building blocks, such as corporate governance and industrial relations, while the synergy of the building blocks influences the behaviour of economic agents in a way that moves beyond the possibilities of certain economic units. Since the integration of the building blocks differs among countries, the authors claim that it could consequently lead to divergence [14]. Finally, this study contributes to the research on the deep roots of development patterns that goes beyond the imported contemporary formal institutions.

The article is structured as follows. Following the Introduction, Section 2 explores institutional change through the lenses of the varieties of capitalism (VoC) approach, while Section 3 elucidates the role of governance in post-socialist transformation and in possible convergence. Based on the insights from the previous sections, Section 4 analyses institutional convergence among Central and Eastern European countries that are, for the purposes of this analysis, divided into groups according to the institutional prototypes of the economic system, i.e., in line with the VoC approach. Additionally, we compare their institutional trajectories with the EU average, as well as with the Mediterranean group of countries. Section 5 brings the discussion, and Section 6 concludes.

2. Institutional Change and Varieties of Capitalism Approach

Until recently, the VoC literature has mostly concentrated on advanced OECD economies and, although highlighting the significance of governance, neglected the role of the state [15]. There is an increasing trend in the number of authors seeking to apply or adjust the VoC framework for post-socialist transition countries [16,17,18,19,20]. In these countries, governments have a big role in the implementation of formal institutional change, which further affects the economic institutions and governance [15]. In terms of VoC, the authors within this research area usually note the likeliness of the dichotomy of LME versus CME to be limiting and possibly leading to an unrealistically reduced complexity of selected transition economies in capitalism, as in other dualistic approaches. However, there is also a claim that, despite its usefulness, this framework “needs to be sensitized to the fundamental structural differences between capitalism in the EU (as well as other ‘advanced countries’ including the USA, Canada, Australia, and Japan) and capitalism in CEECs” [21] (p. 207). Nonetheless, they are useful as a starting point for simultaneously adopting other theories and checking the major differences among the countries, and these differences are sometimes noticeable at first glance. For example, some studies show that the Baltic countries are almost unanimously considered LME, whereas Slovenia, for instance, shows the biggest similarity with a CME model [18].

On the other hand, the criticism tackling the VoC approach when applied to transition economies covers several areas. First, there is little consideration of the influence of the international regime on a country’s economy because it predominantly focuses on large and self-contained economies and yet does not make any distinction between national and sub-national capitalism patterns [17]. At the same time, it is claimed that the VoC concept ignores power relations in the country, particularly those concerning big businesses versus the state [10], bearing in mind that this political power became very relevant in new capitalist states, which were often initially characterised by the unnecessary closeness of business and government. This is also related to the interaction of formal and informal institutional content, something which does not seem to be emphasised enough [17], and to some extent draws upon the missing historical (path-dependent) component in the VoC framework [20].

In order to apply the VoC framework to transition countries, it needs to be contextualised, i.e., it needs to include the important historical and structural characteristics of transition societies, which otherwise seem to be taken for granted [21]. Hall and Thelen’s [22] response to criticism of the non-applicability of VoC in understanding institutional change tackles some of the issues mentioned. They emphasise that VoC is a social actor-centred and broadly rationalist perspective, which considers a political economy as filled with various intertwined institutions. Within this, social actors are purpose-oriented when choosing between institutions, and the VoC considers them to be resources as well, rather than deterrents only, while the persistence of institutions is determined by the benefits that they offer to social and political coalitions. Because of the consequences of institutional interactions, several institutions that belong to the different areas of the political economy influence firms. Namely, Hall and Gingerich [23] state that the institutional framework in countries will influence whether a firm coordinates its activities with competitive market relations or with strategic interactions. In other words, in the case of market imperfections, and with considerable institutional support for the formation of credible obligations, firms are expected to depend more on strategic interactions. On the contrary, in the case of more fluid markets with lower institutional support, firms are expected to rely more on market relations.

Hall and Thelen [22] consider this approach more active in regard to the social actor’s role because it moves away from the view of institutions as passive followers of rules. That notion, coupled with the social actors’ continuous reassessment of the scope of action and coordination, questions the appropriateness of institutions, i.e., how well they serve the interests of relevant social actors. This in turn depends on a series of factors such as institutional interaction, the possibility to find substitutes, and the content of “common knowledge”. Within the VoC approach, Hall and Thelen [22] distinguish between three routes of institutional change: reform, defection, and reinterpretation. While reform corresponds with the top-down approach, defection and reinterpretation bear the same characteristics as a bottom-up approach. More precisely, institutional change is considered to be found regularly in both LMEs and CMEs, and there are multiple agents of adjustments in the economies. Because of their own survival in those changes, companies are more sensitive and responsive than governments.

Próchniak et al. [24] claim that the CEE11 countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia) show the greatest resemblance to the Mediterranean model (Italy or Spain) and the least resemblance to the Scandinavian model (Sweden). Yet, their research also shows that their resemblance to the Mediterranean model is strongly determined by output variables or economic performance. To some extent, Farkas’ [25] study on the governance quality and varieties of capitalism demonstrates similar groups of countries. Namely, those clusters show a core versus periphery division within the EU that appears to imply further EU integration difficulties. Still, there is research showing some progress in real economic convergence between the EU core group of countries and the EU periphery [26,27], particularly regarding the level of income [28]. Ahrens, Schweickert, and Zenker [15] state that the general conclusion stemming from the research within the VoC literature is that governance matters for convergence, but also that the institutional setting varies between the two types of CME and LME.

3. Role of Governance in Post-Socialist Institutional Convergence

There are two ways to create new formal rules. In this article, (in)formal rules and (in)formal institutions are used interchangeably. We follow New Institutional Economics terminology, primarily North’s work [2], whereby it is conventional to subdivide institutions into formal institutions (political and judicial rules, economic rules, contracts) and informal institutions (norms of behaviour, conventions, culture, self-imposed codes of conduct): endogenous creation or importation. In the case of importation, the common concern is their misalignment with locally existing institutions and possibly negative results [9,29,30,31,32,33]. Old inefficient institutions might still be more efficient, at least with respect to temporarily executing tasks, than institutions which have been planned but not put in place. A common concern is the trade-off between the reform of the old institutions and the creation of those that are new [34].

In Eastern European societies, institutional design appears to be highly influenced by the past, which is primarily reflected in the non-institutional legacies that created numerous barriers in the transition process. These include the distorted sectoral structure of the economies, mental and behavioural residues from the communist era, a high concentration and dominance of large enterprises in the industrial sector, loans given based on political criteria, and negative movements in monetary politics [35]. This is mainly because of the different contexts where the policy is going to be applied and the unlikeliness that the pure transplantation of policies and institutions will be successful [36,37,38,39].

In order to assess these issues, one could focus on the institutional “stickiness” concept introduced by Boettke et al. [31] and also considered by Roland [33] (p. 154) to be “a major determinant of the institutional and economic evolution of countries”. Boettke et al. [31] divided institutions into three categories based on the way they came into place (Table 1).

Table 1.

Conceptual categories of institutions based on their origin.

While observing “stickiness”, they consider metis (metis (Greek) as “the set of informal practices and expectations that allow ethnic groups to construct successful trade networks. Knowledge regarding metis is gained only through experience and practice” [31] (p. 338). In New Institutional Economics terminology, it may be explained as a set of informal institutions typical for a certain community/country) to act as glue and suggest that a bigger distance from metis implies the lower stickiness of an institution. IEN institutions are the closest, while FEX institutions are the most remote. Boettke et al. [31] (p. 344) argue that “successful institutional changes in developing parts of the world must have IEN institutions at their core”. However, this still does not mean that any institution that is traceable to IEN institutions will necessarily lead to economic growth. An institution which is consistent with non-productive deeply embedded norms is likely to stick but is also likely to present a barrier to economic prosperity. For example, FEX institutions imposed by force in Stalinist Eastern Europe did stick but did not contribute to economic growth. A more recent example is the post-conflict reconstruction in Bosnia, which despite vast financial foreign aid has been deemed unsuccessful. The reason is found in the insurmountable distance between metis and the imposed FEX institutions. Furthermore, based on transition cases, Boettke et al. [31] claim that metis is not a static concept, and it is possible to change it over time. Until then, it is most probable that institutions that are not in tune with it will fail. In line with the aforesaid, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Schleifer [40] warn that the importation of legal and regulatory rules may lead to inefficiencies since these rules are appropriate for developed countries and may cause significant delays and corruption in developing countries. Clearly, many experts [38,39,41,42] agree that “no size fits all” when implementing institutional reform and stress the dependence on local constraints, circumstances, and opportunities. Additionally, as shown by the research of Jurlin and Čučković [43], the nominal convergence and transfer of EU norms in countries does not ensure their enforcement, and this gap between the adopted and enforced norms is high, while on the other side, the institutional quality remains low.

The reasons for institutional divergence may be found in several factors: differences in social preferences, complementarities in institutional landscape resulting in hysteresis and path dependence, and differences between institutional designs aimed at promoting economic development. In addition to this, numerous studies have shown that high-quality institutions may work in many forms and that economic convergence does not have to be reflected in institutional forms [39]. In relation thereto, Greif [44] claims that understanding the sources of institutional path dependence helps in identifying the factors that may disable the successful adoption of institutions from other countries.

Despite numerous studies, it is still not fully clear which institutional characteristics improve economic performance or which models of the market economy should be imported. In order to explain divergence in the performance of post-communist countries, research on transition was forced to take a broad view under the governance umbrella incorporating corruption, legal frameworks, accountable institutions, and underlying factors such as trust [45]. At the beginning of transition, only a minority of researchers would agree with Fligstein’s [46] (p. 1079) point that states that existing laws and the actions of political and economic elites would result in “a unique blend of property rights, governance structures, and rules of exchange in these societies”. Yet, in retrospect, it became obvious that divergence is rising and that transition countries are “far more heterogeneous than they were twenty years ago” [11] (p. 293). Yet, in a group covering transitional countries, Próchniak and Witkowski [28] demonstrate the existence of GDP β-convergence at a rate of 1.5–2% per year. Recent research also shows that fast reforming transition countries (i.e., countries that applied a ‘shock therapy’ approach) have outperformed the gradual reformers [47].

Dixit [48] sees the overall reform attempts through a governance perspective and defines transition countries as relation-based systems in the process of transformation towards rule-based systems. In that process, the common tipping point is reached when the existing value of social benefits is higher than the investment needed to switch to a more rule-based system [48]. Collectivist societies provide fertile soil for relation-based governance, and they are shown to have worse economic performance in the long-run than individualist societies [44]. In addition, collectivism versus individualism was proven to be the only relevant feature of national culture for economic growth [49] that also affects the quality of government [50].

Evidence has shown that individualism contributes to good governance, whereas collectivism is more likely to contribute to corruption and clientelism [50]. Individualism and distribution of power in society appear to be the only significant predictors of the characteristics of institutional quality [51]. The in-group favouritism that is very typical for collectivist societies, and as such presents an obstacle for the advancement of governance, might be best understood through Granovetter’s [52] embeddedness concept and the over socialised view of society. The underlying idea of social embeddedness is also found in Whitley’s [53] business system approach, a framework in which significant international differences in corporate governance and doing business in general are predominantly explained by nationally specific social institutions.

When seeking to categorise the acquis communautaire into conceptual groups of institutions based on their origin (Table 1), the acquis would fall into exogenous institutions both indigenously (IEX) and foreign-introduced (FEX). The Washington Consensus approach to transition put an emphasis on the adoption of laws that was expected to result in a rapid new equilibrium. Contrary to that, the evolutionary institutionalist perspective argues for a more comprehensive, gradual approach in that regard.

4. Empirical Assessment of Institutional Convergence in CEECs

Although there is no universally accepted definition of governance, and a conceptual framework for governance statistics is still lacking [54], for the purpose of this article, i.e., to investigate the convergence of CEE countries as a potential result of the transfer of Western formal institutions to those countries, the latest edition of the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) dataset was used. Based on a long-standing research programme by the World Bank, the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) capture six key dimensions of governance (Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Lack of Violence, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption) in the period between 1996 and 2019. Thus, in the following lines, we first analyse the institutional quality in CEECs based on the VoC approach, after which we empirically test the σ- and unconditional β-convergence in selected groups of countries.

4.1. Quantitative Analysis of Institutional Quality in EU Based on the VoC Approach

Institutions are recognized as a fundamental determinant of long-run growth in the literature [55]. Additionally, there is a vast amount of literature proving that that institutional convergence is related to convergence in terms of GDP per capita (i.e., real or economic convergence), i.e., previous research shows a strong correlation between good governance and a higher level of per capita GDP. Although there are usually some issues with endogeneity in such research, and the correlation between the two variables does not reveal much information on the direction of causality, it is nonetheless generally accepted that good governance, while important in and of itself, can also help in improving a country’s economic prospects [56], i.e., that the quality of governance matters for growth and development. However, although governance quality in general matters for growth and development, it also varies across dimensions of governance and a country’s level of prosperity. Precisely, according to the contemporary data, most indicators point out that quality of governance, or ‘good governance’, is generally higher on average within the EU-28 member states as compared with other world regions, yet there is significant variation among the countries in the EU [57].

The novelty of our research is that we follow the VoC approach, based on which, taking into consideration institutional prototypes of the economic system [13], the EU countries can be grouped into the following groups of countries: Liberal, Nordic, Continental, Mediterranean, Central and Eastern European countries with a coordinated market system, and Central and Eastern European countries with a liberal market (as presented in the Table 2).

Table 2.

EU countries grouped according to the VoC approach.

When analysing the sources measuring some aspect of the quality of governance in European countries, WGI is considered to provide the best tools to make reliable and meaningful comparisons within the EU at the national level [57]. Additionally, the WGI captures the main components of the EU standard of good governance: liberal democracy and governance capacity [58]. Furthermore, based on a long-standing research program of the World Bank, the WGI captures six key dimensions of governance—Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Lack of Violence, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption—in the period from 1996 to 2019. These indicators evaluate the quality of governance in over 200 countries, from close to 40 sources of information prepared by over 30 organizations worldwide, and have been updated on a yearly basis since 2002. Additionally, these six dimensions of governance should not be considered as being some way independent of one another. Although the main criticisms of this measure are based on the fact that they are all subjective measures, they are nonetheless the most extensive in terms of country coverage and various aspects of institutional quality [4]. According to the WGI aggregation methodology, the six aggregate indicators are reported in two different ways: (1) in their standard normal units, ranging from approximately −2.5 to 2.5, and (2) in percentile rank terms from 0 to 100, with higher values corresponding to better outcomes. The standard normal units are used in the analysis [59].

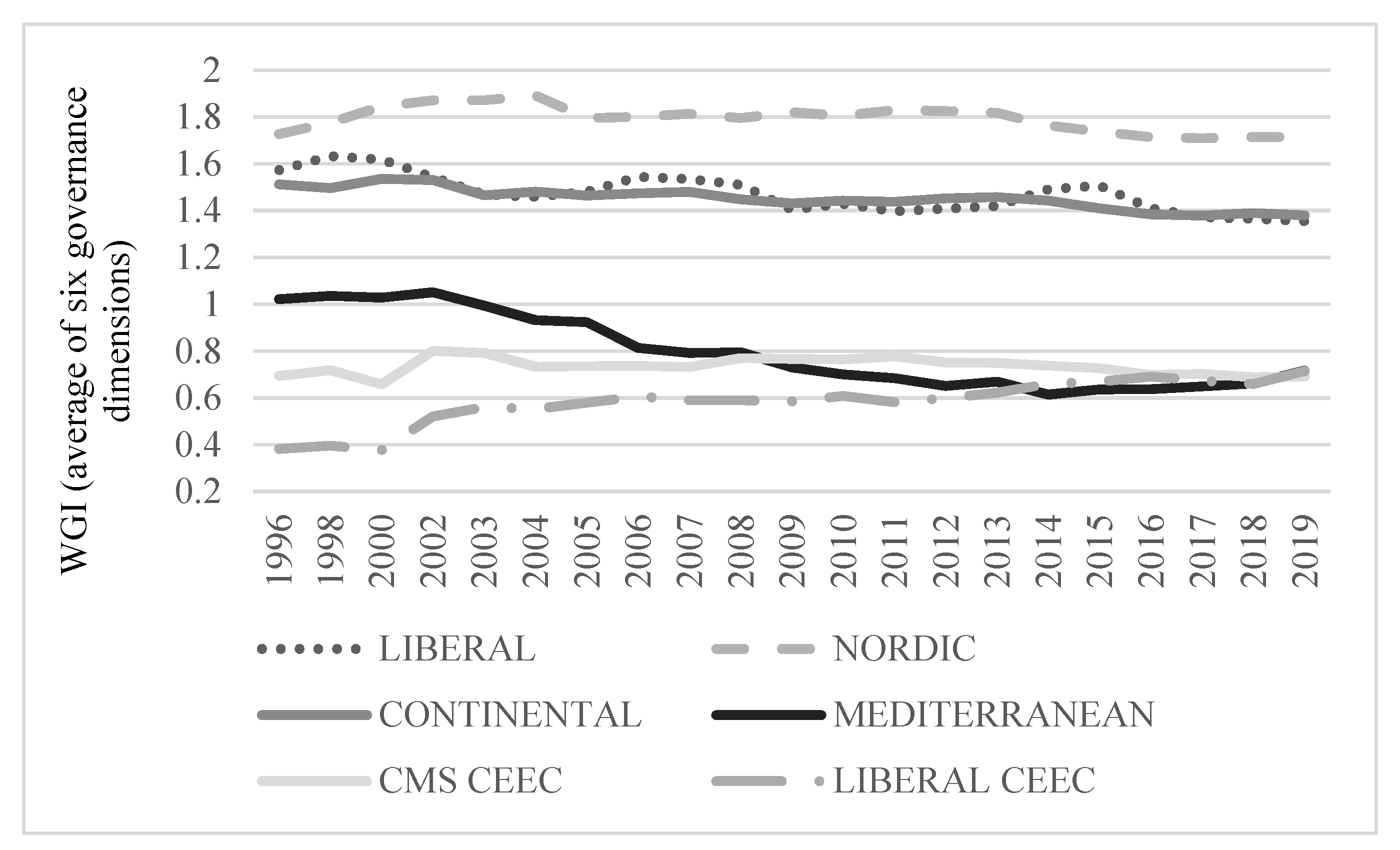

When analysing the changes in WGI (average for all six dimensions) over time (Figure 1), data show a strong persistence in governance scores and regional rankings. We can see that there are two groups of countries from this aspect—there is a significant and consistent gap between the Nordic, Continental, and Liberal countries, on the one hand (first group), and the Mediterranean and CEE countries (second group), on the other hand. Moreover, in the observed period, the Mediterranean countries have even reduced their scores, while CEEC LME countries have improved their scores the most. In terms of policy, the results of descriptive analysis indicate that CEE countries still strive for stronger control of corruption, more operative government, better rule of law, and higher regulatory quality. Based on the trends explored, it is likely to expect the Nordic countries to remain the top performers and Liberal and Continental countries to come closer to them in the medium- or long-run. Yet, it is highly unlikely that Mediterranean and CEEC will join the three leading groups of countries anytime soon. This result is in line with the findings of the University of Gothenburg [57], which highlight that a group of old EU members, such as Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, or Finland, exhibits steadily high levels of quality of government irrespective of the particular index used to capture good governance. In addition to their finding, we have shown that some of the members in that group of countries have surprisingly low levels of governance quality (i.e., Mediterranean countries). Additionally, Glawe and Wagner [5], analysing the formation of institutional convergence clusters within the EU over the period from 2002 to 2018 by using Phillips and Sul’s log t test, pointed to the existence of multiple institutional clubs for the WGI dimensions “government effectiveness”, “regulatory quality”, “rule of law”, and “control of corruption”, as well as for the mean of these four indicators. Precisely, the authors outline a northwest-southeast divide for all indicators, where among the NMS, the Baltic States perform best, whereas the rest of NMS and Mediterranean countries are rather stuck in poor institutional traps.

Figure 1.

Changes over time in WGI, 1996–2018. Source: Authors’ calculation using World Bank—Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) online database [60]. Note: WGI average of six key dimensions of governance: Voice and Accountability (VA), Political Stability and Lack of Violence (PSAV), Government Effectiveness (GE), Regulatory Quality (RQ), Rule of Law (RoL), and Control of Corruption (CoC).

4.2. Sigma (σ) and Unconditional β-Convergence

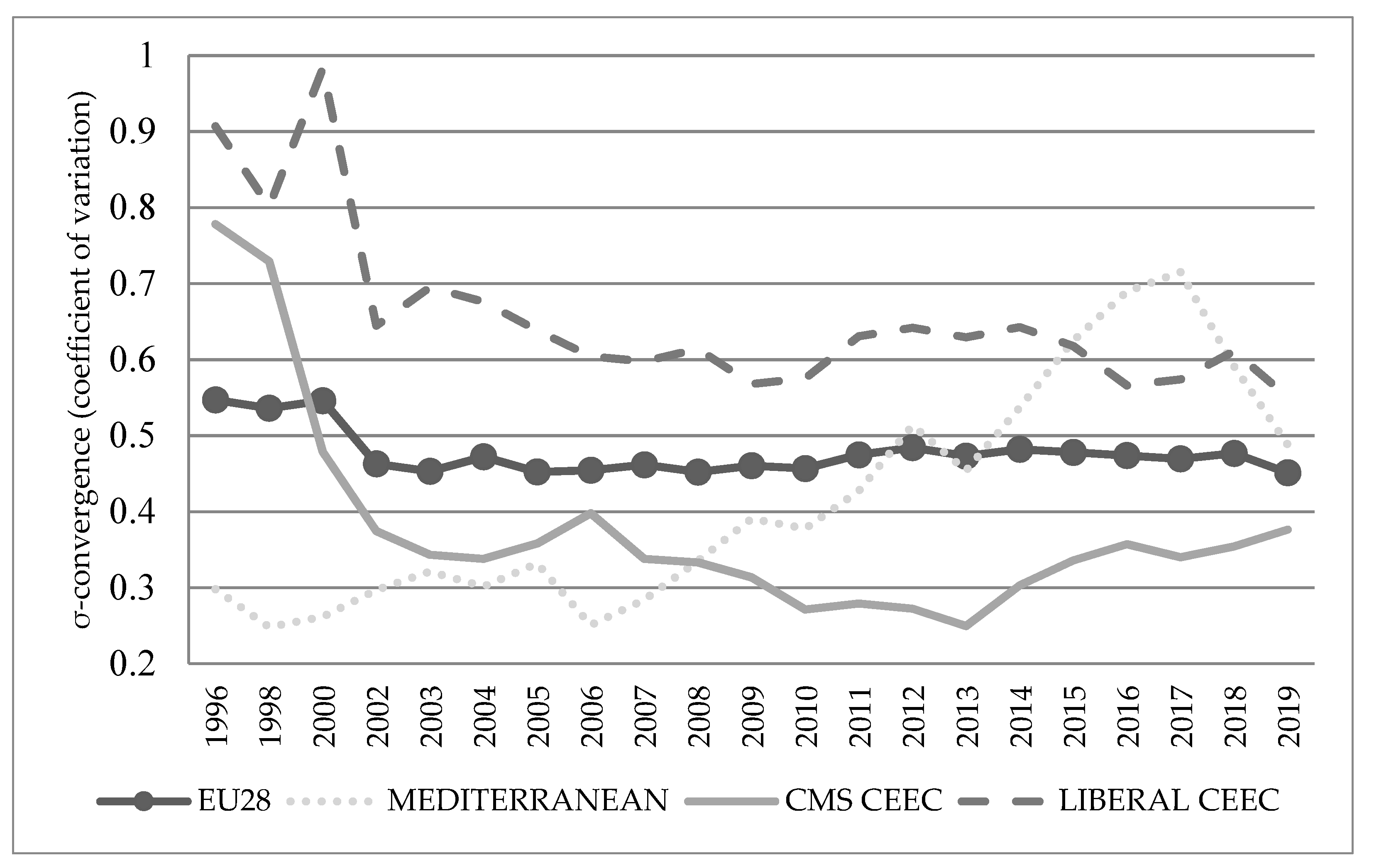

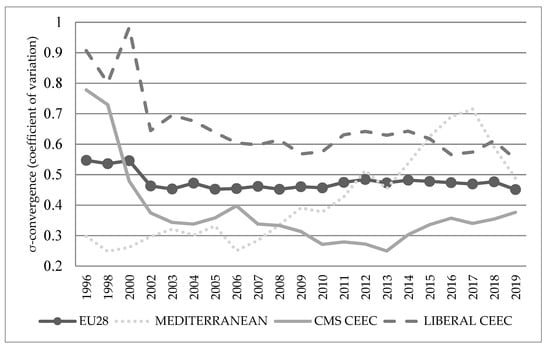

In order to grasp the causes of previously described trends, in further steps, we calculated the coefficient of variation as a measure of dispersion for selected groups of countries in order to test for the σ-convergence (in the period from 1996 to 2019) (Figure 2). The application of σ-convergence is somewhat problematic because the ‘Liberal’ cluster combines two countries only. More generally, based on the low number of observations within some clusters, the variance within clusters is sensitive to changes in one country, and differences between clusters are, hence, difficult to interpret with respect to their significance. Therefore, in the next step, we compare CEECs with the EU28 average on one side and Mediterranean countries on the other side.

Figure 2.

Institutional σ-convergence in CEECs based on VoC approach. Source: Authors’ calculation using World Bank—Worldwide Governance Indicators online database [60].

As it is assumed that σ-convergence is present when the coefficient of variation shrinks between the periods, the presented data show that the largest trend in institutional divergence is recorded in the group of Mediterranean countries.

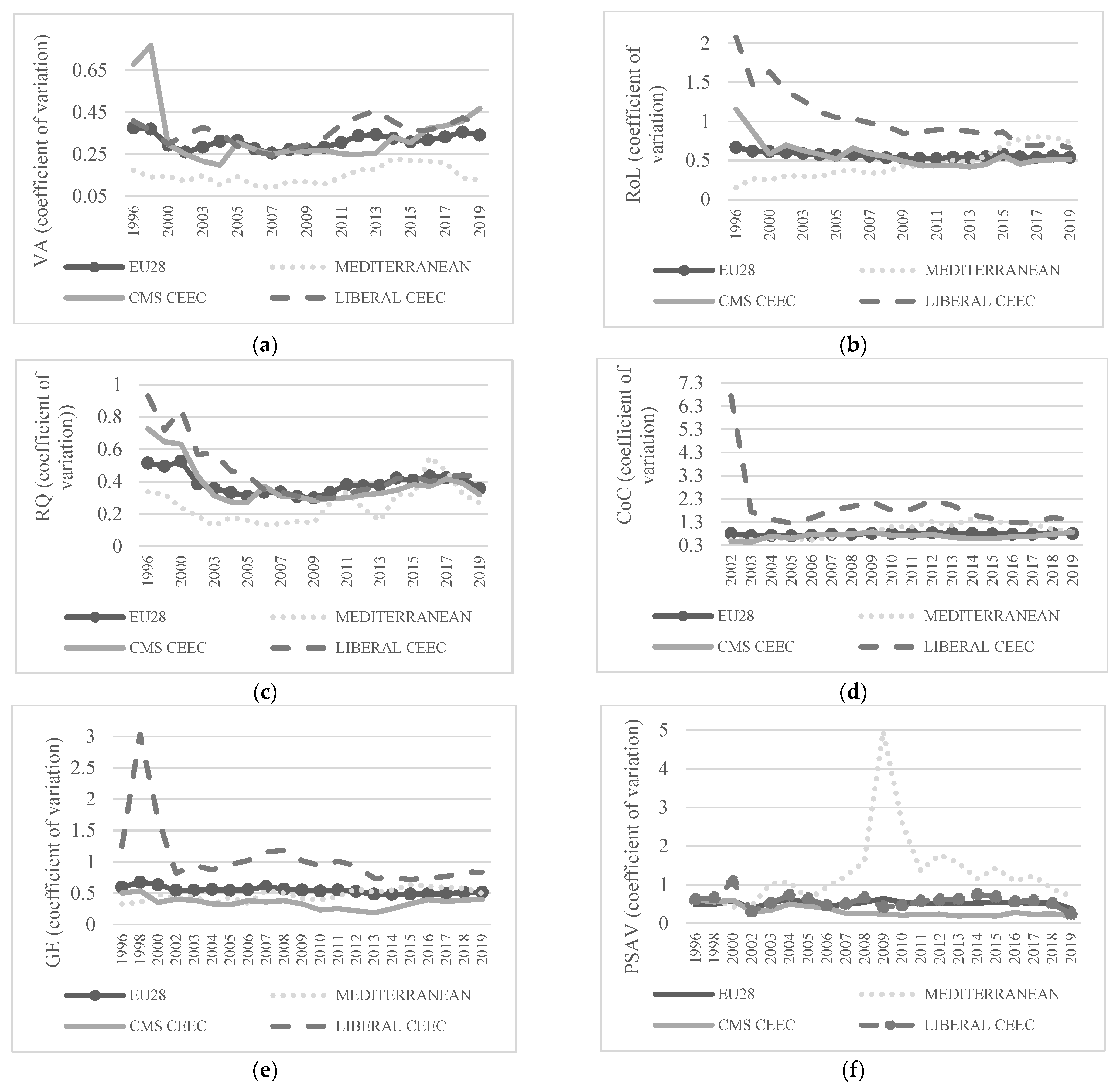

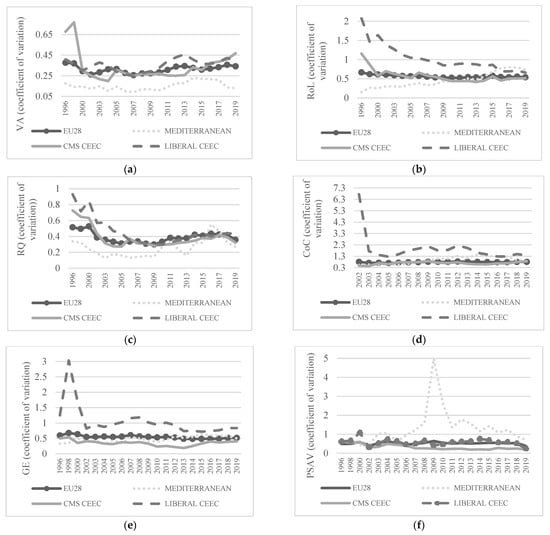

We also look at the σ-convergence for all six dimensions contained in the WGI: Voice and Accountability (VA), Rule of Law (RoL), Regulatory Quality (RQ), Control of Corruption (CoC), Government Effectiveness (GE), and Political Stability and Absence of Violence (PSAV) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Institutional σ-convergence: specific dimensions of WGI. Source: Authors’ calculation using World Bank—Worldwide Governance Indicators online database [60]. Notes: (a) VA (Voice and Accountability), (b) RoL (Rule of Law), (c) RQ (Regulatory Quality), (d) CoC (Control of Cor-ruption), (e) GE (Government Effectiveness), and (f) PSAV (Political Stability and Absence of Violence).

We see differences within various dimensions of WGI, as well as across time, especially before and after the 2008 crisis. In the group of Mediterranean countries, there is an evident trend of divergence in all dimensions, except in Government Effectiveness. In the Liberal CEEC group, there is evident convergence in the Rule of Law dimension for the whole period observed and in the pre-crisis period within the Regulatory Quality dimension. Within the CMS CEEC group, we can see the convergence trends in all dimensions.

In the next step, we test the unconditional beta (β) convergence, performing a cross-section regression analysis in which the change of institutional quality g in the 1996–2019 period is regressed on the initial level of institutional quality :

where the parameter β shows the speed of convergence towards a unique steady state. The negative and significant coefficient implies convergence. Generally, β-convergence models stem from economic growth theories. The models capture the relationship between initial per capita income and subsequent growth. Two models can be used: unconditional β-convergence or conditional β-convergence, which controls for other growth factors. The β-convergence occurs when the parameter β is negative and statistically significant, whereas a positive value of β implies the presence of divergence. Finally, if the parameter β is not statistically significant, we conclude that there is neither convergence nor divergence [3].

We test the convergence for an average of all six dimensions of governance contained in the WGI (IQavg) and the following specific dimensions: rule of law (RoL), regulatory quality (RQ), government effectiveness (GE), and control of corruption (CoC). We selected these four dimensions in accordance with claims of Savoia and Sen [4] who pointed out that these are a very good proxy for all aspects of legal and administrative institutional quality. We also calculate β-convergence for Mediterranean countries and for the EU25 (Cyprus, Malta, and Luxemburg are excluded from the analysis) average, in order to compare their convergence paths to the one of the CEECs.

As one of the contributions of our paper is in introducing the VoC approach into the discussion, we obtained interesting results for countries divided according to this classification (Table 3). At the average level of institutional quality (IQavg), the results show convergence at the level of CMS CEECs and the level of EU25, while in the Mediterranean group of countries, we observe divergence. The results for CMS CEECs show convergence in the dimensions Rule of Law, Regulatory Quality, and Control of Corruption, while the model with the Government Effectiveness dimension is not significant. Next, concerning the Liberal CEECs, the results point to convergence in the Regulatory Quality dimension and divergence in the Rule of Law and Government Effectiveness dimensions. The other models are not significant. The obtained results are in line with some of the previous research that is interpreted in more detail within the discussion in Section 5.

Table 3.

Regression analysis results.

5. Discussion

Mutual rules and laws are supposed to lead to a greater convergence of countries. This particularly tackles the transfer of successful formal institutions from one country to another, usually from a more developed to a less developed country. Since the 1990s and the beginning of post-socialist transformation, institutional and policy transfers were expected to be efficient tools of enhancing socio-economic development. Besides fragmented reform initiatives in the beginning of 1990s, EU accession and the accompanying acquis communautaire some years later were meant to push Eastern European countries closer to Western European countries. However, as we have shown within the descriptive analysis in Section 4.1, i.e., the analysis of the evolution of institutional quality in the EU through time, there are large differences within the EU countries if we divide them according to the VoC approach. The aforementioned findings seem to add more evidence of the greater strength of deep roots in a development pattern than of imported contemporary formal institutions. The findings also provide insights into the rising heterogeneity among transitional societies (in line with [9,10,11,12,13]. For example, we confirm that the process of convergence is more pronounced in the EU as a whole which is in line with the research of López-Tamayo, Ramos, and Suriñach [61] and Schönfelder and Wagner [1]. Precisely, López-Tamayo, Ramos, and Suriñach [61] show that the process of conditional convergence is more pronounced in new EU member states and in the EU as a whole compared to the more competitive economies, and that the speed of conditional convergence has increased during the period after the 2008 crisis. This means that in the most recent years, countries are converging to their own steady state faster than before. The authors conclude that as far as these states are different due to structural factors that cannot be changed in the short-run, absolute differences between countries could increase in the long run. Research conducted by Schönfelder and Wagner [1] raises awareness of potentially failed convergence or even divergence in institutional terms within the EU integration process. Namely, they present evidence for σ-divergence in the area of governance within the first 12 Euro-area members, while they confirm institutional β-convergence in the cluster of EU members and EU aspirants, which is mainly driven by the new Member States and acceding, candidate, and potential candidate countries.

Additionally, we confirm the weak performance and divergence of Mediterranean member states. This is in line with the findings of Tόth and Hajdu [62], who analysed institutional convergence among 10 EU member states that joined the EU in 2004 as well as in four Southern EU members, focusing on the ability of institutions in controlling corruption risks in public procurement. Using the EU TED database, their analysis covered the period from 2006 to 2018. Their results confirm the weak performance of Southern EU member states, along with different results for the EU10, where Slovakia, Estonia, and Lithuania achieved the strongest convergence and the highest institutional quality, and Slovenia and Bulgaria recorded divergence with low institutional quality. In line with Alesina et al. [63], we present evidence on the difference within the specific dimensions of governance, where some countries record convergence, while others record divergence. Specifically, Alesina et al. [63] highlight that although the process of European integration and economic convergence established mutual benchmarks and objectives for institutional improvements, in some institutional dimensions, European countries became more similar, while in others, the opposite happened. More precisely, the authors stress that the quality of the public administrations and of the legal systems did not converge, with Southern Europe falling further behind relative to Northern Europe.

However, there are some methodological issues that should be raised. Since the aspect of unconditional convergence analysed in the paper assumes that all countries have the same characteristics, and, on the other hand, different structural factors could determine whether the countries converge or not, it is necessary to look at institutional convergence as being conditional on factors such as initial GDP levels or human capital levels (as in Hall 2015). Therefore, we see this as a next step in the research, taking into consideration a set of explanatory variables that account for long-run determinants of institutional change, both across countries and over time. Such an approach could help in re-shifting the implications from “What rules to import?” to another important pre-implementation question, “How to adapt them to local realities?”, in order to make them efficient. This is further expected to provide more targeted policy recommendations. In addition, the distinctions and limits of transplanting institutions versus the introduction of mutual institutions should be explored in more detail.

6. Conclusions

This article explores the governance in CEE countries in the period of the last two decades, decades marked by intense changes in Europe. Governance, as an umbrella concept of institutional quality, is selected because of its strong positive correlation with the level of economic development, which has been proven many times in the literature.

The evidence obtained from the empirical analysis does not suggest that there are convergence paths among the groups of EU countries. First, our analysis of trends in WGI scores from 1996 to 2019 indicates that Liberal, Nordic, and Continental countries perform much better than Mediterranean and CEE countries. The countries from the former group all belong to the “old” EU members, and their governance trajectories are quite stable, with Nordic countries being the top performers. The latter group consists of the “new” EU members and Mediterranean countries. The strongest convergence is found within the CMS CEE countries, although not in all WGI dimensions. On the other hand, the selected benchmark group of countries, i.e., the Mediterranean countries, shows institutional divergence. This resulted in recent Mediterranean, CEEC CME, and CEEC LME trajectories being very close.

Rather than proposing several specific policy implications, this research is strongly in favour of context-related principles for the future endeavours of institutional (re)design in transition societies aimed at faster institutional convergence towards the most successful EU members and/or rising economic prosperity. The latter appears to be more important, as heterogeneity is expected to increase, and it may question the former goal. Both theoretical and practical insights in this regard may upgrade the existing development pattern and have further policy implications. Since all transition countries still show significant traces of the past, and it is highly probable that this influence will last, the lessons learned so far can help to avoid common pitfalls in future reform attempts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Š.B.; Data curation, V.V. and M.B.S.; Formal analysis, V.V. and M.B.S.; Investigation, V.V., R.Š.B. and M.B.S.; Methodology, V.V.; Resources, R.Š.B.; Validation, M.B.S.; Writing—original draft, V.V., R.Š.B. and M.B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All links available in the sources/references.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the following conferences for their valuable comments on the previous versions of this paper: The International Academic Conference ‘Thirty Years of Transition’-Ljubo Sirc Centenary Conference in Ljubljana, Slovenia (September 2020), and the 31st Annual EAEPE (European Association of Evolutionary Political Economy) Conference: ‘30 years after the fall of the Berlin wall–What happened to Europe/Where does Europe stand today? What is new in economics?’ in Warsaw, Poland (in September 2019). At the former conference, the paper was awarded one of the three ‘Runners up’ awards in the Best Paper Award contest. The working version of this paper is available at SSRN (Vuckovic et al. 2019).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schönfelder, N.; Wagner, H. Institutional convergence in Europe. Economics: The Open-Access. Open-Assess. E-J. 2019, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-i-Martin, X. Convergence. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, A.; Sen, K. Do we see convergence in institutions? A cross-country analysis. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glawe, L.; Wagner, H. Convergence, Divergence, or Multiple Steady States? New Evidence on the Institutional Development within the European Union. J. Comp. Econ. 2021, 49, 860–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glawe, L.; Wagner, H. Divergence Tendencies in the European Integration Process: A Danger for the Sustainability of the E (M) U? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M. Introduction: A special issue in honoring Janos Kornai. Public Choice 2021, 187, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornai, J. The affinity between ownership forms and coordination mechanisms: The common experience of reform in socialist countries. J. Econ. Perspect. 1990, 4, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teubner, G. Legal Irritants: How Unifying Law Ends Up in New Divergences. In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage; Hall, P.A., Soskice, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 417–441. [Google Scholar]

- King, L. Postcommunist Divergence: A Comparative Analysis of the Transition to Capitalism in Poland and Russia. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2002, 37, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornia, G.A. Transition, Structural Divergence; Performance: Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union during 2000–2007. In Economies in Transition: The Long-Run View; Roland, G., Ed.; United Nations University–World Institute for Development Economics Research; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012; pp. 293–316. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/wp2010-32.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Bohle, D.; Greskovits, B. Capitalist Diversity at Europe’s Periphery; Cornell Univeristy Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlborn, M.; Ahrens, J.; Schweickert, R. Large-Scale Transition of Economic Systems–Do CEECs Converge Toward Western Prototypes? Comp. Econ. Stud. 2016, 58, 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Soskice, D. An Introduction to Varieties of Capitalisms. In Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage; Hall, P.A., Soskice, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahrens, J.; Schweickert, R.; Zenker, J. Varieties of Capitalism, Governance and Government Spending: A Cross-Section Analysis; Kiel Working Paper (No. 1726); Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW): Kiel, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buchen, C. East European Antipodes: Varieties of Capitalism in Estonia and Slovenia. In Proceedings of the Pre-Publication Conference “Varieties of Capitalism in Post-Communist Countries”, Paisley University, Paisley, UK, 23–24 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhnenko, V. What Type of Capitalism in Post-Communist Europe? Poland and Ukraine Compared. Institutional Change in Contemporary European Capitalism: Conflict, Contradiction and Complementarities Conference, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK. 2005. Available online: http://www.policy.hu/mykhnenko/Mykhnenko2005GERPISA.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Feldmann, M. Emerging Varieties of Capitalism in Transition Countries: Industrial Relations and Wage Bargaining in Estonia and Slovenia. Comp. Political Stud. 2006, 39, 829–854. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0010414006288261 (accessed on 3 August 2021). [CrossRef]

- Noelke, A.; Vliegenthart, A. Enlarging the Varieties of Capitalism: The Emergence of Dependent Market Economies in East Central Europe. World Politics 2009, 61, 670–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, L. The Role of Existing Theories and the Need for a Theory of Capitalism in Central Eastern Europe. 2010. Available online: http://www.emecon.eu/fileadmin/articles/1_2010/emecon%201_2010%20King.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- King, L. Central European Capitalism in Comparative Perspective. In Beyond Varieties of Capitalism: Conflict, Contradictions, and Complementarities in the European Economy; Hanké, R., Thatcher, M., Rhodes, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.A.; Thelen, K. Institutional Change in Varieties of Capitalism. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2009, 7, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, P.A.; Gingerich, D.W. Varieties of capitalism and institutional complementarities in the political economy. Br. J. Political Sci. 2009, 39, 449–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Próchniak, M.; Rapacki, R.; Gardawski, J.; Czerniak, A.; Horbaczewska, B.; Karbowski, A.; Towalski, R. The emerging models of capitalism in CEE11 countries—A tentative comparison with Western Europe. Wars. Forum Econ. Sociol. 2016, 7, 7–70. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas, B. Quality of governance and varieties of capitalism in the European Union: Core and periphery division? Post-Communist Econ. 2019, 31, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vamvakidis, A. Convergence in Emerging Europe. East. Eur. Econ. 2009, 47, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Próchniak, M.; Witkowski, B. On the Stability of the Catching-Up Process Among Old and New EU Member States. East. Eur. Econ. 2014, 52, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Próchniak, M.; Witkowski, B. Real β-Convergence of Transition Countries. East. Eur. Econ. 2013, 51, 6–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejovich, S. Understanding the Transaction Costs of Transition: It’s the Culture, Stupid. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2003, 16, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousseau, E.; Garrouste, P.; Raynaud, E. Institutional changes: Alternative theories and consequences for institutional design. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2011, 79, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boettke, P.J.; Coyne, C.J.; Leeson, P.J. Institutional Stickiness and the New Development Economics. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2008, 67, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurkchiyan, M. Russian Legal Culture: An Analysis of Adaptive Response to an Institutional Transplant. Law Soc. Inq. 2009, 33, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, G. The Long-Run Weight of Communism or the Weight of Long-Run History? In Economies in Transition: The Long-Run View; Roland, G., Ed.; United Nations University—World Institute for Development Economics Research; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012; pp. 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Murrell, P. Evolution in Economics and in the Economic Reform of the Centrally Planned Economies; Working Paper; Department of Economics, University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 1991; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.547.8215&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Elster, J.; Offe, C.; Preuss, U. Institutional Design in Post-Communist Societies: Rebuilding the Ship at Sea (Theories of Institutional Design); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dolowitz, D.; Marsh, D. Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making Governance. Int. J. Policy Adm. 2000, 13, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklič, M.; Zagoršek, H. Rationality in Transition: Using Holistic Approach to Rationality to Explain Some Developments in the Slovenian Business System; Working Paper. No. 146; Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Roland, G. Understanding Institutional Change: Fast-Moving and Slow-Moving Institutions. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2004, 38, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodrik, D. One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanez, F.; Shleifer, A. The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 285–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nye, J. Institutions and Institutional Environment. In New Institutional Economics—A Guidebook; Brousseau, E., Glachant, J.-M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornai, J. What Does ‘Change of System Mean’? In From Socialism to Capitalism; Kornai, J., Ed.; Central University Press: Budapest, Hungary, 2008; pp. 123–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jurlin, K.; Čučković, N. Comparative analysis of the quality of European institutions 2003–2009: Convergence or divergence? Financ. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, A. Cultural Beliefs and the Organization of Society: A Historical and Theoretical Reflection on Collectivist and Individualist Societies. J. Political Econ. 1994, 102, 912–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.L. Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance; MIT Press, 2010; Available online: https://mitpress.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.7551/mitpress/9780262014595.001.0001/upso-9780262014595 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Fligstein, N. Markets as Politics: A Political-Cultural Approach to Market Institutions. American Sociological Review. 1996, pp. 656–673. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/209410174_Markets_as_Politics_A_Political-Cultural_Approach_to_Market_Institutions (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Šimić Banović, R.; Basarac Sertić, M.; Vučković, V. The Speed of Large-Scale Transformation of Political and Economic Institutions: Insights from (Post-) Transitional European Union Countries. Hrvat. Komparat. Javna Uprava-Croat. Comp. Public Adm. 2018, 18, 555–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K. Lawlessness and Economics: Alternative Modes of Governance; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gorodnichenko, Y.; Roland, G. Culture, Institutions and the Wealth of Nations; NBER Working Paper No. 16368; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16368.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Kyriacou, A.P. Individualism–collectivism, governance and economic development. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2016, 42, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klasing, M.J. Cultural dimensions, collective values and their importance for institutions. J. Comp. Econ. 2013, 41, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. In The Sociology of Economic Life, 2nd ed.; Granovetter, M., Swedberg, R., Eds.; Westview Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, R. (Ed.) European Business Systems: Firms and Markets in Their National Contexts; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations & Economic Commission for Europe. In-Depth Review of Governance Statistics in the UNECE/OECD Region, ECE/CES/BUR/2016/OCT/2. 2016. Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/documents/ece/ces/bur/2016/October/02_In_depth_review_Governance_final.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 385–472. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Khan, H.; Zhuang, J. Do governance indicators explain development performance? A cross-country analysis. In Governance in Developing Asia: Public Service Delivery and Empowerment; Deolalikar, A.B., Jha, S., Quising, P.F., Eds.; Asian Development Bank: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- University of Gothenburg. Measuring the Quality of Government and Subnational Variation. Report for the European Commission Directorate-General Regional Policy Directorate Policy Development. 2010. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/studies/pdf/2010_government_1.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Schimmelfennig, F. Good governance and differentiated integration: Graded membership in the European Union. Eur. J. Political Res. 2016, 55, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2010. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/3913 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Worldwide Governance Indicators. Available online: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/ (accessed on 7 August 2021).

- López-Tamayo, J.; Ramos, R.; Suriñach, J. Institutional and socio-economic convergence in the European Union. Croat. Econ. Surv. 2014, 16, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, I.J.; Hajdu, M. Corruption, Institutions and Convergence. Studies in Economic Transition. 2021, pp. 195–248. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/h/pal/stuchp/978-3-030-57702-5_9.html (accessed on 6 December 2021).

- Alesina, A.; Tabellini, G.; Francesco, T. Is Europe an Optimal Political Area? In Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 169–213. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/90013171 (accessed on 9 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).