Choosing between Formal and Informal Technology Transfer Channels: Determining Factors among Spanish Academicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Background

2.2. Factors of Knowledge Transfer

2.2.1. Capacity

2.2.2. Motivation

2.2.3. Opportunity

2.2.4. Organizational Justice

- −

- Distributive justice: The degree to which the reward obtained by the academic (economic or curricular benefit, etc.) is in accordance with the effort and sacrifice involved in engaging in a formal or informal transfer activity.

- −

- Procedural justice: The academic’s perception of his or her relationship with the TTO staff (professionalism, effectiveness, etc.).

- −

- Interpersonal justice: The academic’s perception that the treatment received from the TTO is similar to that of others, regardless of seniority or professional category.

- −

- Informational justice: The academic’s perception of whether information related to transfer activities is explained in a personalized, clear, and timely manner.

- −

- In addition to these four traditional dimensions, we agree with Balven et al. [15] on the need to incorporate a fifth dimension: deontological justice. This fifth dimension refers to the academic’s perception of the moral desirability of transfer activities and their relationship with the third mission of the university. Thus, many academics see in the transfer of technology the raison d’être of their research activity, since they consider it morally fair to return to society what it has allowed them to develop thanks to the public funds received to finance their research projects. Others, on the contrary, consider that transfer activities “distract” the academic from the real missions of academia [19].

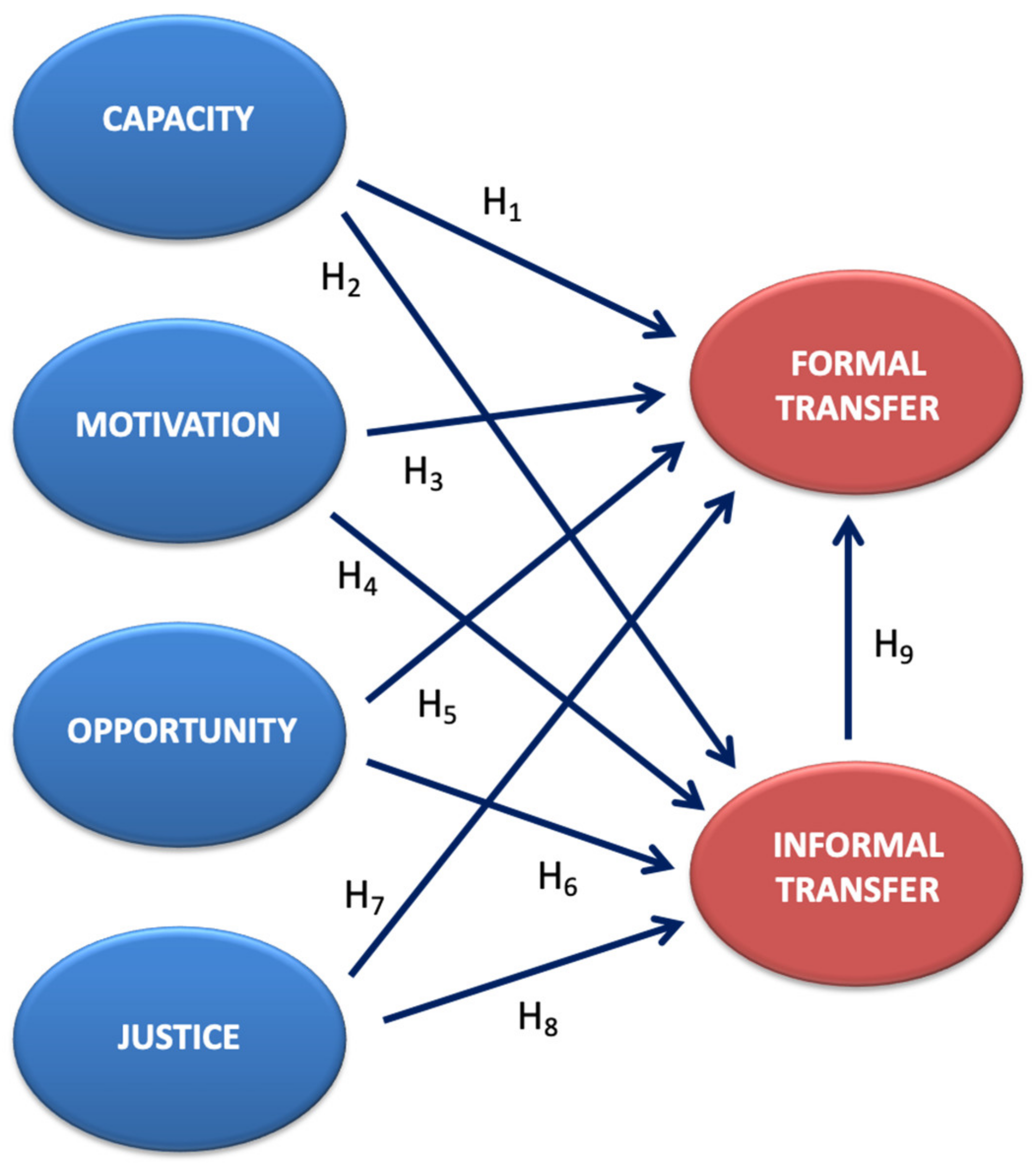

2.3. The Proposed Model

2.3.1. Capacity

2.3.2. Motivation

2.3.3. Opportunity

2.3.4. Justice

- Age

- Gender

- Academic field

- Geographic location

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

- (a)

- sharing research results on open science platforms;

- (b)

- a doctoral student promoting the creation of a company;

- (c)

- a doctoral student being hired by a company;

- (d)

- an academic researcher answering questions from other colleagues in open network forums;

- (e)

- a researcher participating in forums, seminars, and conferences where research results are openly shared; and

- (f)

- an investigator advising a company without signing any contract or agreement.

- (a)

- taking out a patent license;

- (b)

- creating a university spin-off; and

- (c)

- signing an agreement or contract for the provision of services to companies outside the university.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belitski, M.; Aginskaja, A.; Marozau, R. Commercializing university research in transition economies: Technology transfer offices or direct industrial funding? Res. Policy 2019, 48, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F.T.; Agung, S.D.; Jiang, L. University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2007, 16, 691–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimpe, C.; Hussinger, K. Formal and informal knowledge and technology transfer from academia to industry: Complementarity effects and innovation performance. Ind. Innov. 2013, 20, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.D.; Xia, J.; Liu, W.; Tsai, S.B. An empirical study on sustainable innovation academic entrepreneurship process model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gomez, F.-I.; Miranda, F.J.; Chamorro Mera, A.; Pérez Mayo, J. The spin-off as an instrument of sustainable development: Incentives for creating an academic USO. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M. Academic entrepreneurship, technology transfer and society: Where next? J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 39, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguntuase, O.J. Academic entrepreneurship, bioeconomy, and sustainable development. In Handbook of Research on Approaches to Alternative Entrepreneurship Opportunities; Leitão Dantas, J.G., Carvalho, L.C., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Meléndez, A.; Aguila-Obra, D.; Rosa, A.; Lockett, N.; Fuster, E. Entrepreneurial universities and sustainable development: The network bricolage process of academic entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, A.M.; Moore, R.W.; Rossy, G.L.; Neupert, K.; Napier, N.K.; Jones, D.E.; Harvey, M. Academic entrepreneurship: Views on balancing the Acropolis and the Agora. J. Manag. Inq. 2003, 12, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Aldridge, T.T.; Oettl, A. The knowledge filter and economic growth: The role of scientist entrepreneurship. Kauffman Found. Large Res. Proj. Res. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, C.S. Academic capitalism and university incentives for faculty entrepreneurship. J. Technol. Transf. 2006, 31, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.M.; Roijakkers, N.; Fini, R.; Mortara, L. Leveraging open innovation to improve society: Past achievements and future trajectories. R&D Manag. 2019, 49, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Wu, C.; Yang, W. A new approach for the cooperation between academia and industry: An empirical analysis of the triple helix in East China. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2016, 21, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D. Effectiveness of technology transfer policies and legislation in fostering entrepreneurial innovations across continents: An overview. J. Technol. Transf. 2019, 44, 1347–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balven, R.; Fenters, V.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D. Academic entrepreneurship: The roles of identity, motivation, championing, education, work-life balance, and organizational justice. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenbaum, D.; Scott, C. Hochschullehrerprivileg—A modern incarnation of the professor’s privilege to promote university to industry technology transfer. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2010, 15, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Gianodis, P.T.; Phan, P. Sidestepping the Ivory Tower: Rent Appropriations through Bypassing of US Universities; Mimeograph; University of Georgia: Athens, Georgia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Markman, G.; Gianiodis, P.; Phan, P. An agency theoretic study of the relationship between knowledge agents and university technology transfer offices. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 55, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, A.N.; Siegel, D.S.; Bozeman, B. An empirical analysis of the propensity of academics to engage in formal university technology transfer. In Universities and the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem; Audretsch, D.B., Link, A.N., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Q.T.; Jasovska, P.; Rammal, H.G.; Schlenker, K. Formal-informal channels of university-industry knowledge transfer: The case of Australian business schools. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 17, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, R.; Rasmussen, E.; Siegel, D.; Wiklund, J. Rethinking the commercialization of public science: From entrepreneurial outcomes to societal impacts. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Krahmer, F.; Schmoch, U. Science-based technologies: University–industry interactions in four fields. Res. Policy 1998, 27, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomariov, B.; Boardman, P.C. The effect of informal industry contacts on the time university scientists allocate to collaborative research with industry. J. Technol. Transf. 2008, 33, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A.; Meyer, M.; Von Tunzelmann, N. Becoming an entrepreneurial university? A case study of knowledge exchange relationships and faculty attitudes in a medium-sized, research-oriented university. J. Technol. Transf. 2008, 33, 259–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M.; Walsh, K. University–industry relationships and open innovation: Towards a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A.; Atwater, L.E.; Link, A.N. Toward a model of the effective transfer of scientific knowledge from academicians to practitioners: Qualitative evidence from the commercialization of university technologies. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2004, 21, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzfeld, H.R.; Link, A.N.; Vonortas, N.S. Intellectual property protection mechanisms in research partnerships. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Gianiodis, P.T.; Phan, P.H. Full-time faculty or part-time entrepreneurs. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2008, 55, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Kim, Y.G.; Bock, G.W. Identifying different antecedents for closed vs open knowledge transfer. J. Inf. Sci. 2010, 36, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Lockett, N.; Johnston, L. Recognising “open innovation” in HEI-industry interaction for knowledge transfer and exchange. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 540–560. [Google Scholar]

- D’Este, P.; Perkmann, M. Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. J. Technol. Transf. 2011, 36, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghe, A.; Knockaert, M.; Piva, E.; Wright, M. Are researchers deliberately bypassing the technology transfer office? An analysis. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Göktepe-Hultén, D. What drives academic patentees to bypass TTOs? Evidence from a large public research organisation. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, A.N.; Siegel, D.S. Generating science-based growth: An econometric analysis of the impact of organizational incentives on university–industry technology transfer. Eur. J. Financ. 2005, 11, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscio, A.; Vallanti, G. Perceived obstacles to university–industry collaboration: Results from a qualitative survey of Italian academic departments. Ind. Innov. 2014, 21, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liao, Z. The effect of university–industry collaboration policy on universities’ knowledge innovation and achievements transformation: Based on innovation chain. J. Technol. Transf. 2020, 45, 522–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.; Link, A. Assessing the impact of organizational practices on the relative productivity of university technology transfer offices: An exploratory study. Res. Policy 2003, 32, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; McEvily, B.; Reagans, R. Managing knowledge in organizations: An integrative framework and review of emerging themes. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethner, M.; Obschonka, M.; Silbereisen, R.K.; Cantner, U. Scientists’ transition to academic entrepreneurship: Economic and psychological determinants. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Goethner, M.; Silbereisen, R.K.; Cantner, U. Social identity and the transition to entrepreneurship: The role of group identification with workplace peers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pérez, V.; Esther Alonso-Galicia, P.; Del Mar Fuentes-Fuentes, M.; Rodriguez-Ariza, L. Business social networks and academics’ entrepreneurial intentions. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014, 114, 292–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, M.; Silbereisen, R.K.; Cantner, U.; Goethner, M. Entrepreneurial self-identity: Predictors and effects within the theory of planned behavior framework. J. Bus. Psychol. 2014, 30, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, J.; Thompson, L.; Van Boven, L. Learning negotiation skills: Four models of knowledge creation and transfer. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Phan, P.H. Analyzing the effectiveness of university technology transfer: Implications for entrepreneurship education. In University Entrepreneurship and Technology Transfer; Libecap, B., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bradford, UK, 2006; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.; Silberman, J. University technology transfer: Do incentives, management, and location matter? J. Technol. Transf. 2003, 28, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lach, S.; Schankerman, M. Royalty sharing and technology licensing in universities. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2004, 2, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhart, B.; Fang, M. Pay, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, performance, and creativity in the workplace: Revisiting long-held beliefs. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka-Kobayashi, T. Institutional factors for academic entrepreneurship in publicly owned universities in Japan: Transition from a conservative anti-industry university collaboration culture to a leading entrepreneurial university. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2019, 24, 423–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Open innovation: Past research, current debates, and future directions. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lockett, A.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M.; Ensley, M.D. The creation of spin-off firms at public research institutions: Managerial and policy implications. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A. On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 386–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelle, J.J.; Rupp, D.E.; Brockner, J. Taking a multifoci approach to the study of justice, social exchange, and citizenship behavior: The target similarity model. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 841–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Rodell, J.B. Justice, trust, and trustworthiness: A longitudinal analysis integrating three theoretical perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1183–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B. Innovation and Industry Evolution; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, F.J.; Chamorro, A.; Rubio, S. Determinants of the intention to create a spin-off in Spanish universities. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, F.J.; Chamorro, A.; Rubio, S. Re-thinking university spin-off: A critical literature review and a research agenda. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 43, 1007–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Casero, J.C.; Hernández-Mogollón, R.; Roldán, J.L. A structural model of the antecedents to entrepreneurial capacity. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 30, 850–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, M.; Grinevich, V. The nature of academic entrepreneurship in the UK: Widening the focus on entrepreneurial activities. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCIU. Datos y Cifras del Sistema Universitario Español. Curso 2018/2019; Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://www.ciencia.gob.es/portal/site/MICINN/menuitem.26172fcf4eb029fa6ec7da6901432ea0/?vgnextoid=364e006e96052710VgnVCM1000001d04140aRCRD (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Rahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and Validity Assessment; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1979; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technol. Stud. Spec. Issue Res. Methodol. 1995, 2, 294–324. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T.S.H.; Srivastava, S.C.; Jiang, L. Trust and electronic government success: An empirical study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2008, 25, 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Wright, M. Academic entrepreneurship: Time for a rethink? Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Universe | Teaching and Research Staff of the 82 Spanish Universities (115,332 Individuals) |

|---|---|

| Geographic scope | Spain |

| Data collection method | Online survey |

| Sample size | 1215 questionnaires received |

| Sample error | For a 95% confidence level and P = Q, the error for the whole sample is ±2.8% |

| Fieldwork | January 2020 |

| Constructs | Loading Factors | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Ave |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity Obschonka et al. [40] and Fernández-Pérez et al. [41] | 0.803 | 0.859 | 0.504 | |

| CAPAC1: I have confidence in my ability to transfer valuable knowledge to society. | 0.726 | |||

| CAPAC2: I have the knowledge to solve problems relevant to the productive sector of my environment. | 0.759 | |||

| CAPAC4: I am qualified to be the promoter of a spin-off. | 0.647 | |||

| CAPAC5: I am qualified to sign a service contract (art. 83) with a company outside the university. | 0.732 | |||

| CAPAC6: I am qualified to advise others on the implications of my research results. | 0.702 | |||

| CAPAC7: Many of my colleagues believe that the results of my research are of significant value for society. | 0.687 | |||

| Opportunity Díaz-Casero et al. [58] | 0.814 | 0.867 | 0.569 | |

| OPORT1: My university has adequate procedures and policies to facilitate the transfer of results to the productive sector. | 0.854 | |||

| OPORT2: My university has adequate procedures and policies to locate companies that would be interested in the results obtained by my research group. | 0.814 | |||

| OPORT3: My university has adequate procedures and policies to assess the value of research results (prototypes, market tests, etc.). | 0.732 | |||

| OPORT4: In my region, there are many opportunities for the efficient transfer of knowledge from the university and public research centers to the productive sector. | 0.694 | |||

| OPORT6: In my region, there is adequate support from public administrations for scientists to market their ideas through new and growing companies. | 0.662 | |||

| Motivation Miranda et al. [56] | 0.808 | 0.865 | 0.561 | |

| MOTIVA2: I hope to receive rewards from my academic position for transferring my knowledge to society. | 0.722 | |||

| MOTIVA3: I hope to expand my knowledge by transferring my knowledge to society. | 0.791 | |||

| MOTIVA4: I hope to improve my scientific productivity by transferring my knowledge to society. | 0.737 | |||

| MOTIVA5: I hope to improve my teaching quality by transferring my knowledge to society. | 0.751 | |||

| MOTIVA6: I hope to improve my prestige and reputation by transferring my knowledge to society. | 0.743 | |||

| Justice Balven et al. [15] | 0.749 | 0.833 | 0.556 | |

| JUST2: I consider that the procedures established by the TTO (Office of Transfer of Research Results) and my university to manage the transfer activities are adequate. | 0.719 | |||

| JUST3: I consider that the attention I receive from TTO staff is attentive and professional and similar to that of my colleagues regardless of their seniority and professional status. | 0.817 | |||

| JUST4: I consider that the information received by my university about the carrying out of transfer activities has been complete and received at the right time. | 0.757 | |||

| JUST5: I consider transfer activities to be morally desirable. | 0.683 | |||

| Formal Technology Transfer | 0.668 | 0.812 | 0.590 | |

| FORMAL1: Patent license. | 0.744 | |||

| FORMAL2: Creation of spin-off companies. | 0.767 | |||

| FORMAL3: Signing of agreements/contracts for provision of services with companies outside the university. | 0.792 | |||

| Informal Technology Transfer | 0.613 | 0.795 | 0.563 | |

| INFORMAL2: Some of my doctoral students have promoted the creation of a company. | 0.759 | |||

| INFORMAL3: Some of my doctoral students have obtained work in a company. | 0.770 | |||

| INFORMAL6: I have advised or collaborated informally with companies without signing any agreement or contract. | 0.722 |

| Capacity | Justice | Motivation | Opportunity | Formal TT | Informal TT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | 0.710 | |||||

| Justice | 0.389 | 0.746 | ||||

| Motivation | 0.447 | 0.375 | 0.749 | |||

| Opportunity | 0.229 | 0.513 | 0.195 | 0.754 | ||

| Formal Transfer | 0.457 | 0.252 | 0.177 | 0.139 | 0.768 | |

| Informal Transfer | 0.406 | 0.195 | 0.202 | 0.114 | 0.464 | 0.751 |

| Capacity | Justice | Motivation | Opportunity | Formal TT | Informal TT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | ||||||

| Justice | 0.454 | |||||

| Motivation | 0.561 | 0.426 | ||||

| Opportunity | 0.264 | 0.707 | 0.227 | |||

| Formal Transfer | 0.574 | 0.308 | 0.204 | 0.178 | ||

| Informal | 0.565 | 0.246 | 0.265 | 0.155 | 0.701 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vega-Gomez, F.I.; Miranda-Gonzalez, F.J. Choosing between Formal and Informal Technology Transfer Channels: Determining Factors among Spanish Academicians. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052476

Vega-Gomez FI, Miranda-Gonzalez FJ. Choosing between Formal and Informal Technology Transfer Channels: Determining Factors among Spanish Academicians. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052476

Chicago/Turabian StyleVega-Gomez, Francisco I., and Francisco J. Miranda-Gonzalez. 2021. "Choosing between Formal and Informal Technology Transfer Channels: Determining Factors among Spanish Academicians" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052476

APA StyleVega-Gomez, F. I., & Miranda-Gonzalez, F. J. (2021). Choosing between Formal and Informal Technology Transfer Channels: Determining Factors among Spanish Academicians. Sustainability, 13(5), 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052476