The Creation and Operation Strategy of Disney’s Mulan: Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Discount

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Studies Related to Disney Movies

2.2. Cultural Appropriation in Film Creation

2.3. Cultural Discounts in Film Operations

- Q1:

- How do Chinese audiences perceive and evaluate the live-action version of Mulan? What dimensions of perception do they have for these perceptions and emotions?

- Q2:

- What is the knowledge and understanding of the film’s creative team? How do these understandings differ from the perception of Chinese audiences? What are the reasons for the difference?

- Q3:

- Does the acceptance of Mulan in China contradict the theory of cultural discount? Why is there a cultural discount in the local Chinese market when cultural appropriation is used as a creative method of Mulan (which originated in China)? What are the strategies for future film creation and operation?

3. Methodology and Material

3.1. Research Methods

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Data Extraction

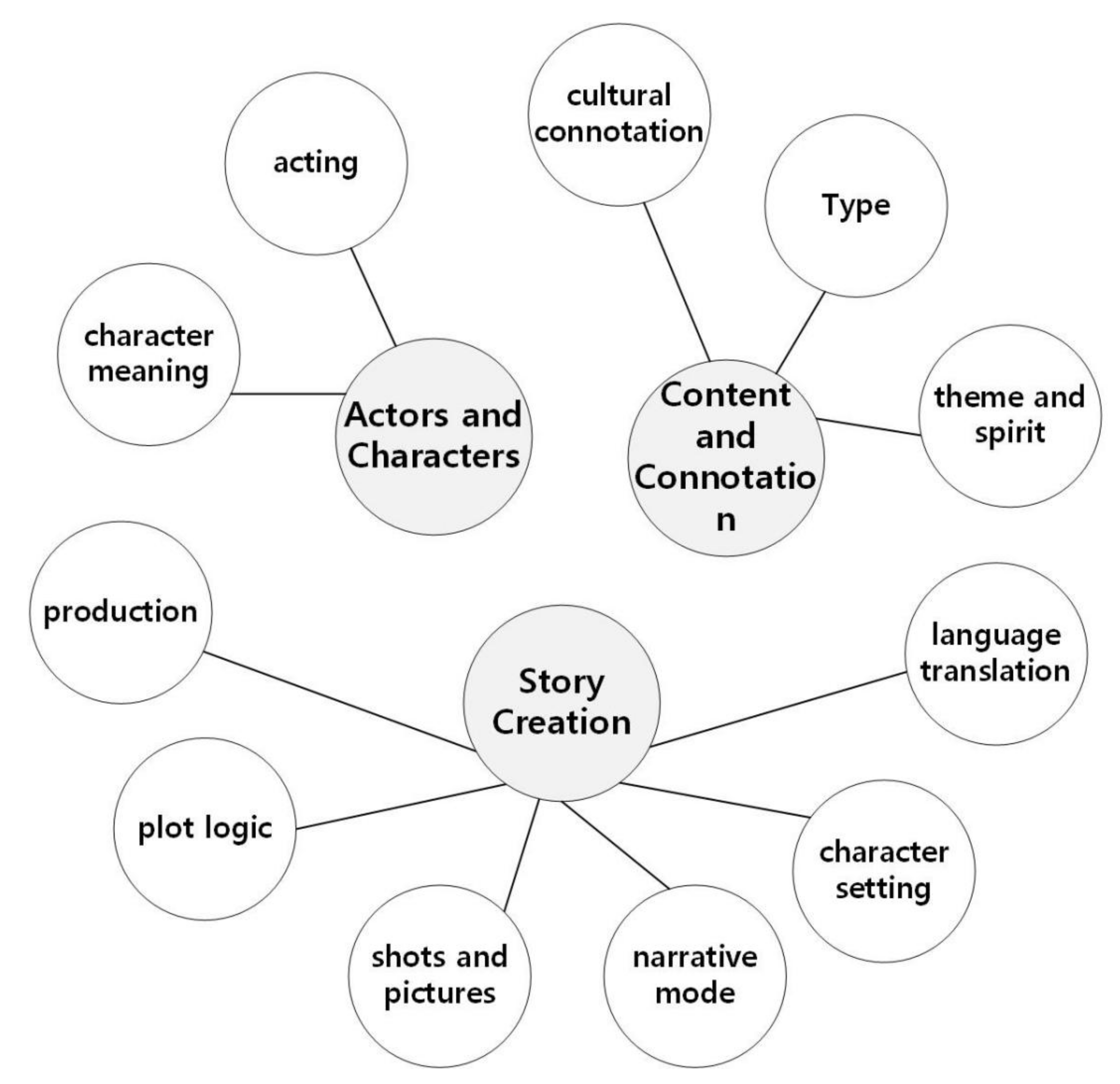

4. Content Analysis and Coding Results

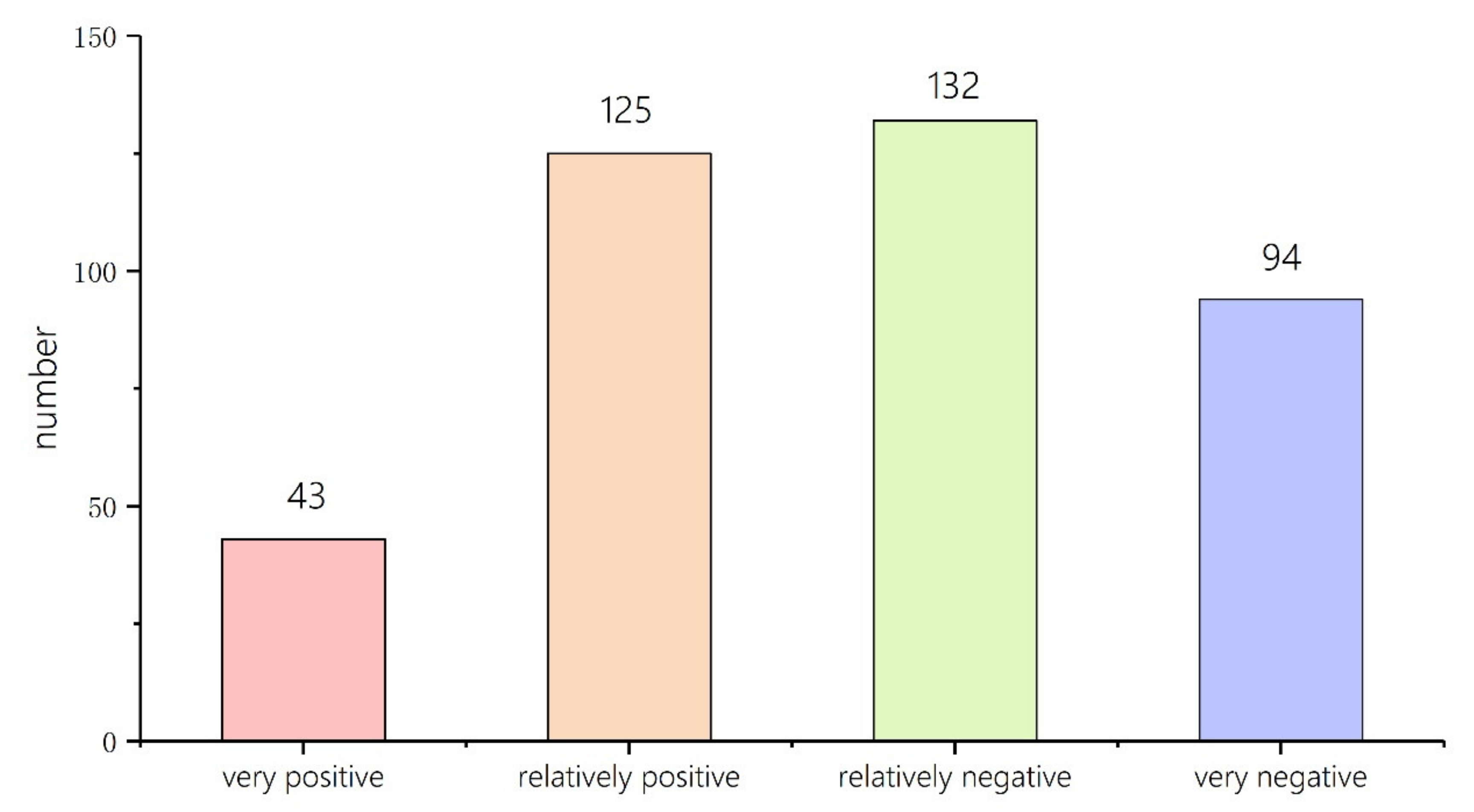

4.1. Chinese Audience’s Acceptance and Understanding of the Film

4.1.1. Short Comments

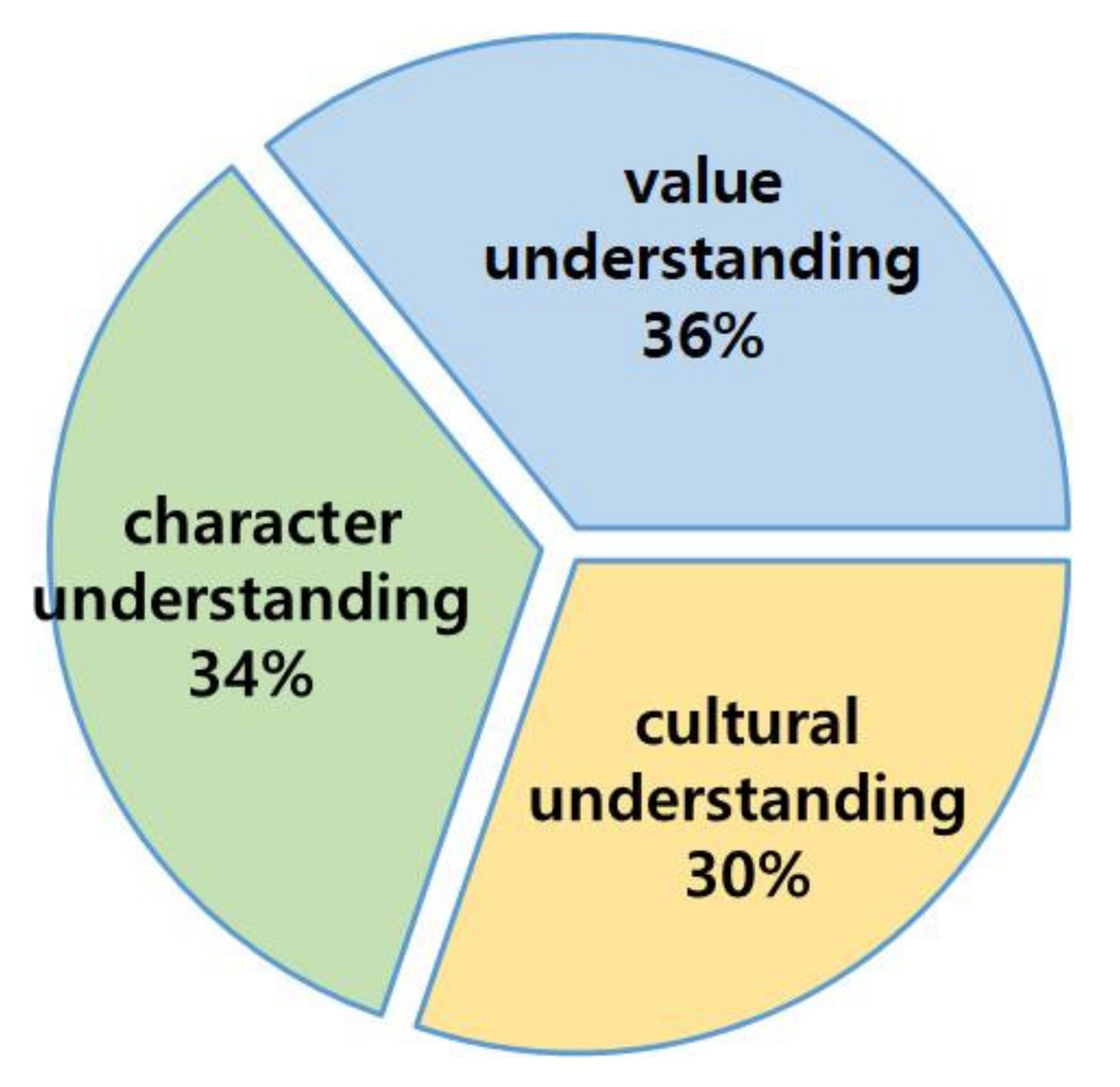

4.1.2. Film Review

4.2. The Director and the Creative Team’s Understanding of the Film

5. Discussion

5.1. Differences in Understanding

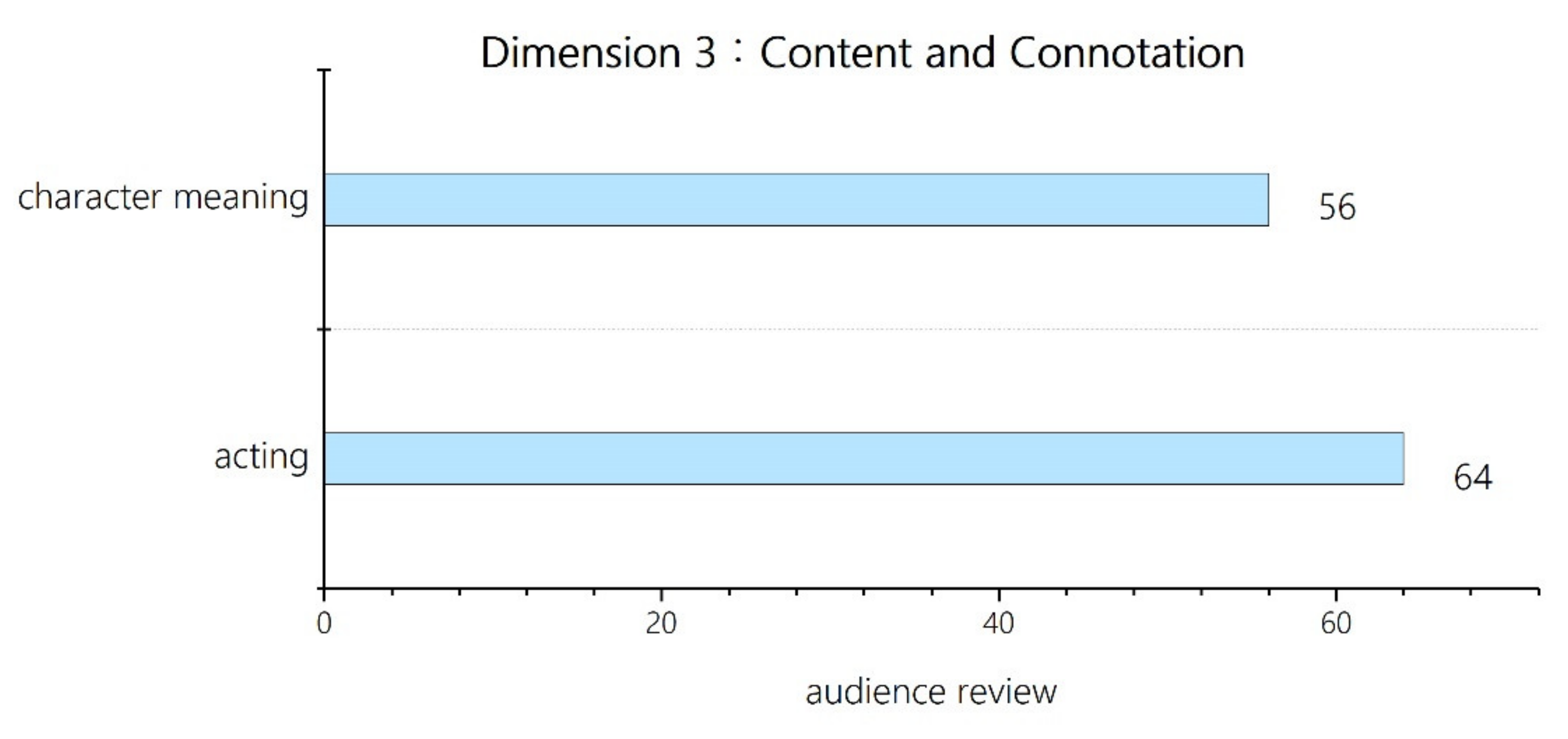

- The difference between the spirit of the main idea and the understanding of the characters. It must be pointed out that the director’s understanding of Mulan’s story is not completely wrong. In ancient China, the reasons why the story of Mulan has been handed down from thousands of years ago to the present day lie in its feminism. The story breaks the traditional gender norms, which is consistent with the western feminist discourse to some extent. The most important narrative of this story for Disney is the gender issue, which they put as the core, constructing the contradiction between the genders, and exploring the conflict between the whole society and the individual development during the process of creation and operation [48]. However, this practice actually hides the spiritual value of Mulan in China. In the perception of Chinese people, filial piety and defense of the country are her most valuable qualities. However, these qualities are interpreted and alienated by Disney as a sign of Mulan’s personal value after the failure of the blind date, which shows her strong individualism. Disney films have made her almost a “superhero” when creating and operating in the Hollywood context [49].

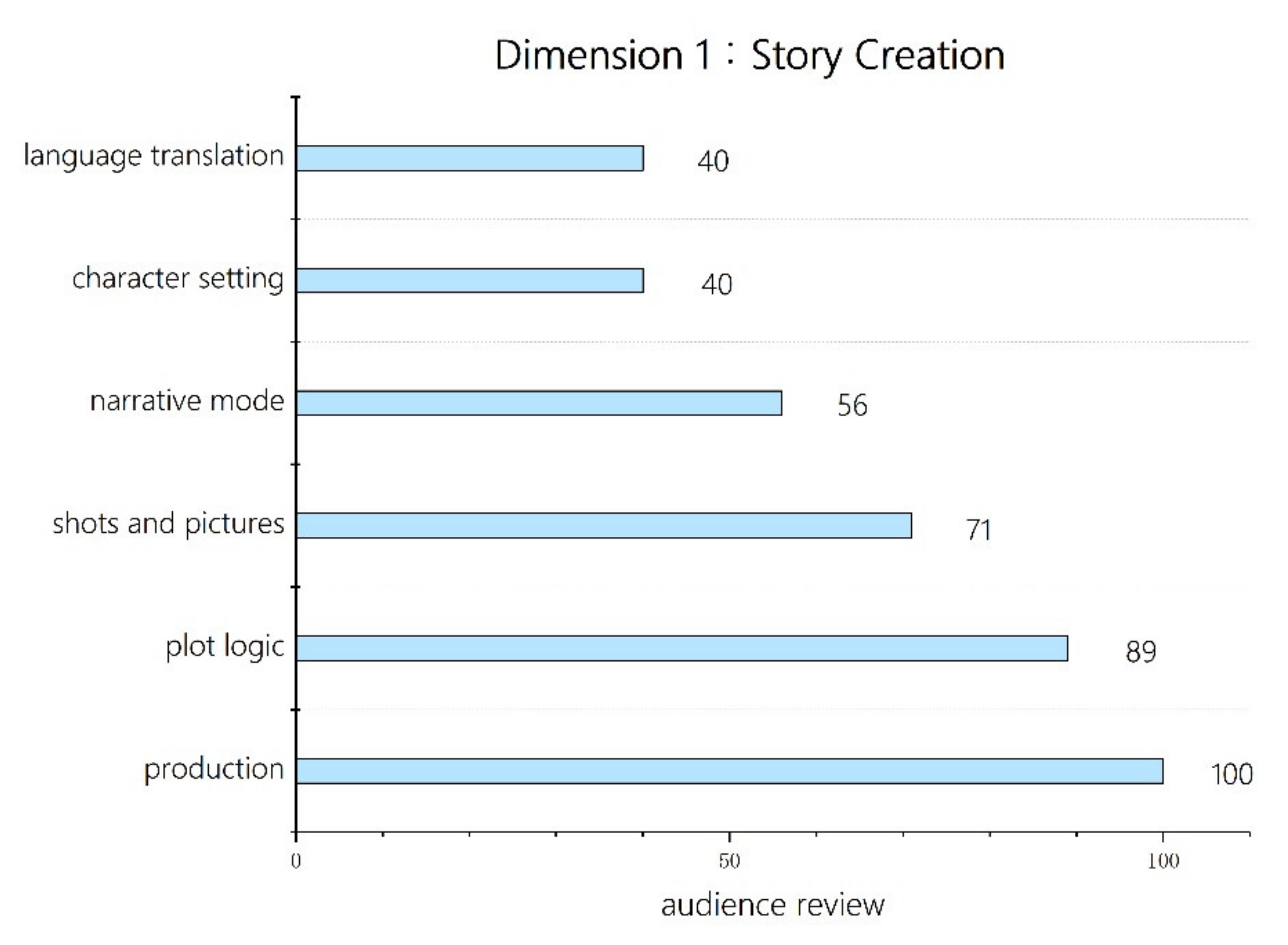

- Lack of attention to story creation. Obviously, the creative team paid little attention to the problems of story creation and paid no attention to the narrative mode and logical structure of the story during the creation and operating process, which is the focus of the Chinese audience when watching. In addition to the cultural connotation, audiences are more concerned about whether the characters’ behaviors are logical and whether the story is told in an attractive way, which determines whether the audience can resonate with the movie. This kind of problem seems to be less forgivable by Chinese audiences than cultural differences. Apparently, the film’s portrayal of Xianniang was most criticized by audiences, who felt that the characters lacked the necessary growth process. Therefore, there is a big problem in the logic of the characters’ behavior before and after, and the audience cannot be persuaded. Such omissions in the characterization of characters occur in more than one place in the film, which is a big mistake in film creation and an important reason why the film gets poor reviews from the Chinese audience in the operation process.

- A wrong perception of Chinese culture. Although directors have made a lot of efforts to understand Chinese culture, their understanding of Chinese culture is limited to the elements and symbols, and they have little understanding of the real cultural connotation. As a result, Chinese elements can be seen everywhere in the film creation and operation, but only on a surface level without reaching the core. The false geographical perception of the creative team in Mulan was the most criticized by Chinese audiences: the earth buildings of Fujian Province in the north, the meadows and snowy mountains of New Zealand, the untimely couplets, and lanterns, etc. This is a typical Western cultural world-building. It only develops a basic sense of Chinese image when viewing [50]. In fact, Disney’s dynamic rewriting of Mulan resulted in the perpetualization of the paradigm of Middle Eastern factionalism in the Western context and simplified the folk narrative into a static and unified whole [51].

5.2. Corresponding Strategy

5.2.1. To Grasp the Theme of the Original Story

5.2.2. To Emphasis More on Story Creation

5.2.3. To Learn Other Cultures

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

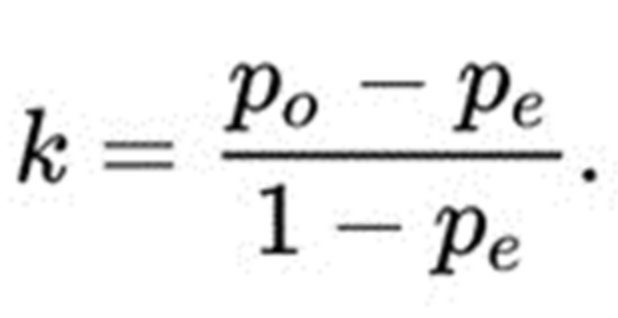

| Node | Material Resource | Kappa | Consistency (%) | Inconsistency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| story creation | Five-star film review | 0 | 97.94 | 2.06 |

| story creation | Four-star film review | 0.0673 | 95.49 | 4.51 |

| story creation | Three-star film review | 0.1776 | 96.22 | 3.78 |

| story creation | Two-star film review | 0.3392 | 97.12 | 2.88 |

| story creation | One-star film review | 0.2926 | 97.35 | 2.65 |

| content and connotation | Five-star film review | 0 | 98.69 | 1.31 |

| content and connotation | Four-star film review | 0.1846 | 97.69 | 2.31 |

| content and connotation | Three-star film review | 0.1329 | 97.16 | 2.84 |

| content and connotation | Two-star film review | 0.1886 | 97.92 | 2.08 |

| content and connotation | One-star film review | 0.2886 | 96.97 | 3.03 |

| actor and character | Five-star film review | 0 | 98.59 | 1.41 |

| actor and character | Four-star film review | 0.092 | 98.58 | 1.42 |

| actor and character | Three-star film review | 0.1731 | 98.94 | 1.06 |

| actor and character | Two-star film review | 0.1128 | 99 | 1 |

| actor and character | One-star film review | 0.343 | 98.76 | 1.24 |

References

- Kohli, G.S.; Yen, D.; Alwi, S.; Gupta, S. Film or Film Brand? UK Consumers’ Engagement with Films as Brands. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wormer, K.; Juby, C. Cultural representations in Walt Disney films: Implications for social work education. J. Soc. Work 2016, 16, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prévot-Julliard, A.-C.; Julliard, R.; Clayton, S. Historical evidence for nature disconnection in a 70-year time series of Disney animated films. Public Underst. Sci. 2014, 24, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, A.P.S. An Approach to Finding Teaching Moments on Families and Child Development in Disney Films. Acad. Psychiatry 2014, 39, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, J.; Latham, K.; Fernandez-Baca, D. Who Cares for the Kids? Caregiving and Parenting in Disney Films. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 36, 1957–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, M. Animation, Branding and Authorship in the Construction of the ‘Anti-Disney’ Ethos: Hayao Miyazaki’s Works and Persona through Disney Film Criticism. Animatation 2016, 11, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, V. ‘What Do We Get from a Disney Film if We Cannot See It?’: The BBC and the ‘Radio Cartoon’ 1934–1941. Hist. J. Film Radio Telev. 2018, 39, 290–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Vijver, L. Going to the exclusive show: Exhibition strategies and moviegoing memories of Disney’s animated feature films in Ghent (1937–1982). Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2015, 19, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjirbag, M.A. Reforming Borders of the Imagination: Diversity, Adaptation, Transmediation, and Incorporation in the Global Disney Film Landscape. Jeun. Young People Texts Cult. 2019, 11, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytry, J. Walt Disney and the creation of emotional environments: Interpreting Walt Disney’s oeuvre from the Disney studios to Disneyland, CalArts, and the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT). Rethink. Hist. 2012, 16, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, K.; Greene, H. Customer Loyalty the Disney Way. Am. Int. J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 2020, 13, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, V. What Is Organizational Imprinting? Cultural Entrepreneurship in the Founding of the Paris Opera. Am. J. Sociol. 2007, 113, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.A. From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation: A Review and Reconceptualization of Cultural Appropriation. Commun. Theory 2006, 16, 474–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmoro, M.; Pinto, D.C.; Herter, M.M.; Nique, W. Traditionscapes in emerging markets. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 15, 1105–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shugart, H.A. Counterhegemonic acts: Appropriation as a feminist rhetorical strategy. Q. J. Speech 1997, 83, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, C. Pranking rhetoric: “culture jamming” as media activism. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 2004, 21, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buescher, D.T.; Ono, K.A. Civilized Colonialism:Pocahontasas Neocolonial Rhetoric. Women’s Stud. Commun. 1996, 19, 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.O. Profound Offense and Cultural Appropriation. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2005, 63, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, C. African Appropriations: Cultural difference, mimesis, and media. Africa 2017, 87, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamoon, D. Class S: Appropriation of ‘lesbian’ subculture in modern Japanese literature and New Wave cinema. Cult. Stud. 2021, 35, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raundalen, J. A Communist Takeover in the Dream Factory—Appropriation of Popular Genres by the East German Film Industry. Slavonica 2005, 11, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurendeau, G. Arts and the Re-appropriation of Culture in Native Societies in Quebec, Canada: The Production of “N’teishkan”, a Documentary Film about Traditional Knowledge. Int. J. Arts Soc. Annu. Rev. 2012, 6, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharat, M. Going global: Filmic appropriation of Jane Austen in India. South Asian Popul. Cult. 2020, 18, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, S. Updating Addison: Culture, Appropriation and The Connoisseur. Forum Mod. Lang. Stud. 2014, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Naylor, S. Appropriation, Culture and Meaning in Electroacoustic Music: A composer’s perspective. Organ. Sound 2014, 19, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, K. Equity in Music Education: Cultural Appropriation Versus Cultural Appreciation—Understanding the Difference. Music. Educ. J. 2020, 106, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, C.; Mirus, R. Reasons for the US Dominance in International Trade in Television Programs. Media Cult. Soc. 1988, 10, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, W.D.; McKenzie, J. The Changing Role of Hollywood in the Global Movie Market. J. Media Econ. 2012, 25, 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.M.; Bradley, F. Cultural Distance and Psychic Distance: Two Peas in a Pod? J. Int. Mark. 2006, 14, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vany, A.; Walls, W.D. Uncertainty in the Movie Industry: Does Star Power Reduce the Terror of the Box Office? J. Cult. Econ. 1999, 23, 285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.L.F. Cultural Discount and Cross-Culture Predictability: Examining the Box Office Performance of American Movies in Hong Kong. J. Media Econ. 2006, 19, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pan, H.R.; Zhu, N.; Cai, S. East Asian films in the European market: The roles of cultural distance and cultural specificity. Int. Mark. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, L.; Natividad, G. Movie release strategy: Theory and evidence from international distribution. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2020, 29, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Ji, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Q. Branding Cultural Products in International Markets: A Study of Hollywood Movies in China. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, F.L.F. Cultural discount of cinematic achievement: The academy awards and U.S. movies’ East Asian box office. J. Cult. Econ. 2009, 33, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Konara, P.; Ling, H.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y. Behind film performance in China’s changing institutional context: The impact of signals. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2017, 35, 63–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Bayus, B.L.; Yi, Y.; Kim, J. Local consumers’ reception of imported and domestic movies in the Korean movie market. J. Cult. Econ. 2014, 39, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jensen, M. Audience Heterogeneity and the Effectiveness of Market Signals: How to Overcome Liabilities of Foreignness in Film Exports? Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1360–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.W.; Govindaraju, A. Explaining Global Box-Office Tastes in Hollywood Films: Homogenization of National Audiences’ Movie Selections. Commun. Res. 2010, 37, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.; Ko, D. Consumer Affinity for Foreign Countries, Film Attendance, and Interest in Purchasing Products from Foreign Countries: An Exploratory Study of Korea and Ireland. Int. J. Hum. Ecol. 2016, 17, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baek, Y.M.; Kim, H.M. Cultural Distance and Foreign Drama Enjoyment: Perceived Novelty and Identification with Characters. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2016, 60, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Changing patterns of foreign movie imports, tastes, and consumption in Australia. J. Cult. Econ. 2014, 39, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.S.; Greene, W.H.; Douglas, S.P. Culture Matters: Consumer Acceptance of U.S. Films in Foreign Markets. J. Int. Mark. 2005, 13, 80–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Song, R. The Roles of Cultural Elements in International Retailing of Cultural Products: An Application to the Motion Picture Industry. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaveras, G.; Gomez-Herrera, E.; Martens, B. Cross-border circulation of films and cultural diversity in the EU. J. Cult. Econ. 2018, 42, 645–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliashberg, J.; Shugan, S.M. Film Critics: Influencers or Predictors? J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, T.L.D.; Nishijima, M.; Fava, A.C.P. Do consumer and expert reviews affect the length of time a film is kept on screens in the USA? J. Cult. Econ. 2018, 43, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danya, L.; Chun, Z. An Analysis of Mulan Adapted by Disney from a Gender Perspective. Nankai J. (Philos. Lit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 26, 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, K. Mulan from the perspective of Comparative Culture. Movie Lit. 2010, 17, 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoqiang, H. Mulan: Disney’s Princess and Family-country Imagination. Film Art 2020, 65, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis. Arts 2020, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. Mulan in China and America: From Premodern to Modern. Comp. Lit. East West 2018, 2, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuying, L. Female warriors: A reproduction of patriarchal narrative of Hua Mulan in The Red Detachment of Women (1972). Media Int. Aust. 2020, 176, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L. Cultural Variation from the Perspective of Reception—A Case Study of the Story of Mulan in the United States. J. Beijing Union Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2017, 15, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Jingwei, Z. Media Change and Modern Inheritance of Folk Narration—Taking Mulan Legend as an Example. Cult. Herit. 2019, 13, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaodong, L.; Gaoxiang, L. Hua Mulan: Style Subversion of Classical Narration and Reconstruction and Analysis of the Female Subjectivity. Contemp. Youth Res. 2016, 34, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Minghua, X.; Danni, L. Emotion resolution and integration: The communication medium and identification path of “Chinese stories” intercultural communication. Mod. Commun. (J. Commun. Univ. China) 2019, 41, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, M.; Pattnaik, C.; Lu, Q. (Steven) Innovation in social media strategy for movie success. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, L.; Uitermark, J.; Boy, J.D. Filtering feminisms: Emergent feminist visibilities on Instagram. New Media Soc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinta, J.V. “A Girl Worth Fighting For”: Transculturation, Remediation, and Cultural Authenticity in Adaptations of the “Ballad of Mulan”. Southeast Asian Rev. Engl. 2018, 55, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, C.; Zhiyi, C.I.P. Operation Strategy of Harry Potter Series Works from Meta-media Perspective. Movie Lit. 2020, 27, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kedi, Z.; Guangjin, T. The Evolution of Brand Intercultural Communication Theory: From the Perspective of Cultural Psycho-logical Distance. Contemp. Commun. 2017, 33, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gundle, S. ‘We Have Everything to Learn from the Americans’: Film Promotion, Product Placement and Consumer Culture in Italy, 1945–1965. Hist. J. Film Radio Telev. 2020, 40, 55–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaenssle, S.; Budzinski, O.; Astakhova, D. Conquering the Box Office: Factors Influencing Success of International Movies in Russia. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2018, 17, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Audience Cognition | The Audience Emotion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Words | Frequency | Dimension | Words | Frequency | Dimension | Words | Frequency |

| Story Creation | story | 68 | Actors and Characters | Liu Yifei | 98 | Positive | expectant | 17 |

| scenario | 60 | character | 40 | good | 15 | |||

| special effect | 16 | acting | 40 | moving | 8 | |||

| picture | 13 | witch | 33 | excellent | 7 | |||

| setting | 13 | Gong li | 27 | amazing | 5 | |||

| scene | 12 | actor | 26 | Negative | awkward | 35 | ||

| action | 11 | villain | 14 | bad | 31 | |||

| costume | 10 | emperor | 14 | poor | 25 | |||

| core | 9 | act | 11 | one star | 24 | |||

| emotion | 9 | Jet Li | 9 | disappointing | 16 | |||

| design | 9 | Content and Connotation | culture | 54 | waste | 10 | ||

| plot | 8 | female | 46 | unreasonable | 9 | |||

| making | 8 | women’s rights | 23 | unaccustomed | 9 | |||

| aesthetic | 8 | era | 10 | gross | 7 | |||

| martial arts | 8 | identity | 10 | boring | 7 | |||

| war | 7 | fairytale | 9 | no good | 7 | |||

| logic | 7 | history | 9 | nondescript | 6 | |||

| value | 7 | self | 8 | failure | 6 | |||

| shot | 7 | tradition | 8 | unevaluated | 6 | |||

| music | 7 | growth | 8 | mess | 5 | |||

| rhythm | 7 | nation | 7 | |||||

| style | 6 | politics | 5 | |||||

| texture | 5 | country | 5 | |||||

| worth | 5 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, R.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y. The Creation and Operation Strategy of Disney’s Mulan: Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Discount. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052751

Chen R, Chen Z, Yang Y. The Creation and Operation Strategy of Disney’s Mulan: Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Discount. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052751

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Rui, Zhiyi Chen, and Yongzhong Yang. 2021. "The Creation and Operation Strategy of Disney’s Mulan: Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Discount" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052751

APA StyleChen, R., Chen, Z., & Yang, Y. (2021). The Creation and Operation Strategy of Disney’s Mulan: Cultural Appropriation and Cultural Discount. Sustainability, 13(5), 2751. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052751