Abstract

The rapid and widespread of COVID-19 has caused severe multifaceted effects on society but differently in women and men, thereby preventing the achievement of gender equality (the 5th sustainable development goal of the United Nations). This study, using data of 355 teleworkers collected in Hanoi (Vietnam) during the first social distancing period, aims at exploring how (dis)similar factors associated with the perception and the preference for more home-based telework (HBT) for male teleworkers versus female peers are. The findings show that 56% of female teleworkers compared to 45% of male counterparts had a positive perception of HBT within the social distancing period and 63% of women desired to telework more in comparison with 39% of men post-COVID-19. Work-related factors were associated with the male perception while family-related factors influenced the female perception. There is a difference in the effects of the same variables (age and children in the household) on the perception and the preference for HBT for females. For women, HBT would be considered a solution post-COVID-19 to solve the burden existing pre-COVID-19 and increasing in COVID-19. Considering gender inequality is necessary for the government and authorities to lessen the adverse effects of COVID-19 on the lives of citizens, especially female ones, in developing countries.

Keywords:

telework; telecommuting; COVID-19; ICT; pandemic; social distancing; preference; perception; gender inequality; Hanoi 1. Introduction

COVID-19, caused by a new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in Wuhan (China) in December 2019 before unprecedentedly disseminating across the world, thereby becoming a pandemic [1]. Compared to previous pandemics, such as MERS, Ebola, SARS, and H1N1, COVID-19 is far more serious in terms of transmissions [2]. Unfortunately, due to the unavailability of vaccines and specific treatment [3], non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce the physical interactions and thus prevent the boom in COVID-19 infections have been adopted widely [4]. A variety of forms of social distancing and lockdown have been applied, such as maintaining a distance between persons in public places (e.g., buses and supermarkets), closure of schools/universities, canceling public events, and restricting going out for unnecessary purposes [5,6]. Such measures have triggered a profound shift from physical to virtual forms for familiar activities [7]. A typical example is home-based telework (HBT), which enables a dramatic reduction in face-to-face communications in workplaces. A wide range of companies from different sectors either required or allowed their workers to perform HBT [8]. A study from Australia [9] reported the average rate of working from home at 0.86 days per week prior to COVID-19 but at 2.4 days during the first wave of the pandemic. In line with the Australian evidence, recent research carried out in developed countries in Europe and the USA emphasized the growth in implementing teleworking [4,10,11]. Little known, however, is the adoption of HBT in developing countries. Additionally, most studies [4,10,11] focus mainly on descriptive statistics rather than on influential factors because HBT is treated as part of a broad topic, including changes in travel behavior and in other e-activities such as online shopping. Research on the perception (i.e., the way that a teleworker thinks about his/her experience in HBT) and the preference for HBT (i.e., whether a worker desires HBT or whether a teleworker desires more HBT) during the COVID-19 pandemic is rare. It is important to note that a good perception may lead to a preference, and thus a decision on re-adopting teleworking. In this sense, analyzing perception and preference is vital for studying the prevalence of HBT post-COVID-19.

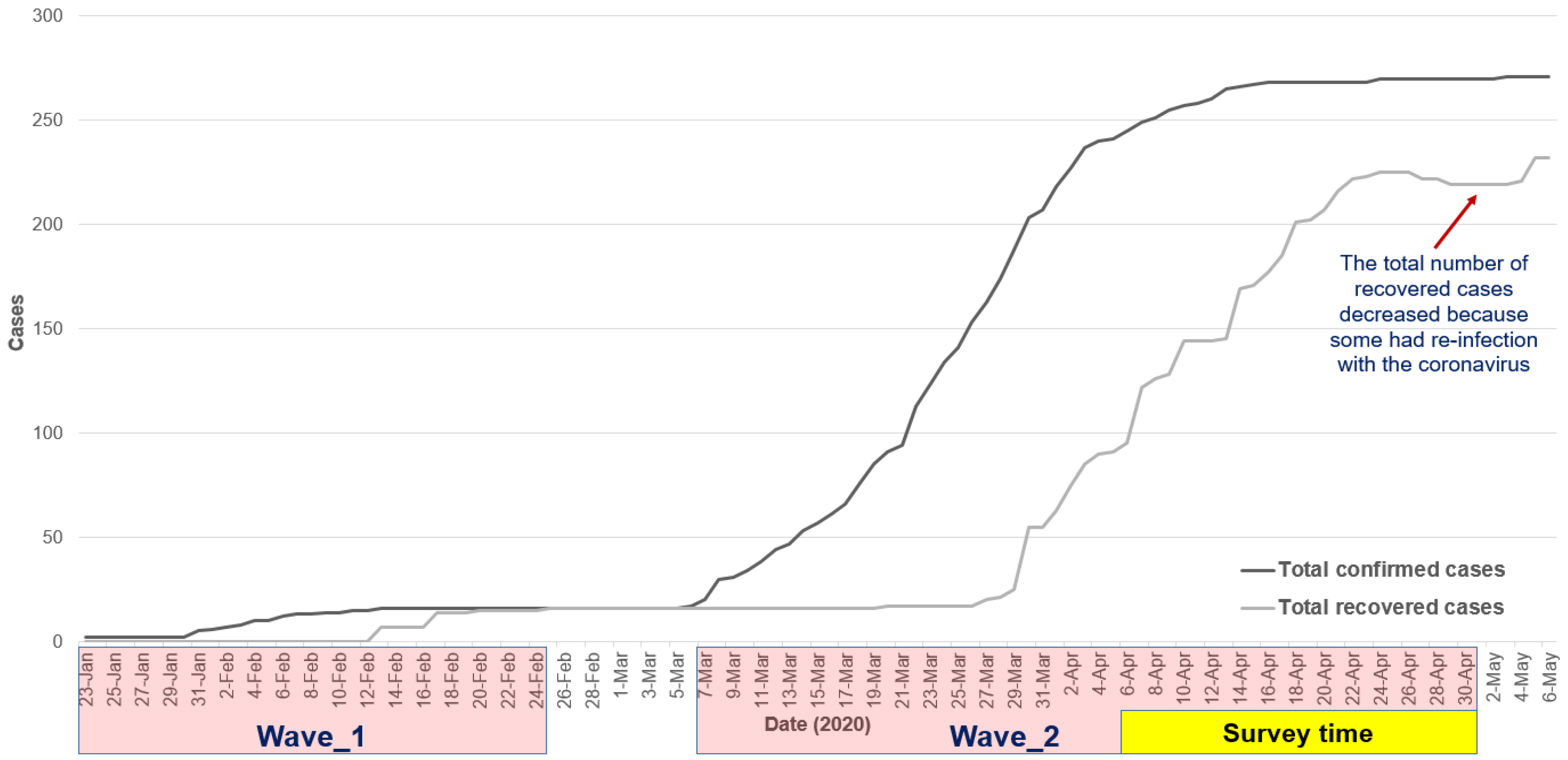

As regards the progression of COVID-19 in Vietnam, until the time of this study, there were two waves of COVID-19 (see Figure 1). The first confirmed case was detected in Vietnam on 23 January 2020 and the last community transmission of the first wave was recorded on 25 February. To suppress the spread of COVID-19, the Vietnamese government had early preparation and prompt actions [12]. Infection clusters and symptomatic persons were put in quarantine while environmental sanitization, hand washing, and wearing masks in public places were highly recommended [6]. The second phase began with the detection of the 17th confirmed case in Hanoi (the capital of Vietnam), which had been safe in the first wave. Afterwards, the stably increasing number of COVID-19 cases and the occurrence of epicenters induced the government to mandate the first nationwide social distancing directive, which was valid from 1 April. Complying with the social distancing guideline, companies had to reduce the physical interaction at workplaces by requiring or encouraging employees to work at home. Consequently, HBT, which had been novel pre-COVID-19, was undertaken substantially. Owing to the strict implementation of safety measures, no community infection with COVID-19 was found after mid-April. The Vietnamese government lifted social distancing in Hanoi on 30 April. A recent study [13] published interesting knowledge on factors affecting HBT using the data of 355 teleworkers collected in Hanoi within the social distancing course.

Figure 1.

The progression of COVID-19 in Vietnam and survey time.

The COVID-19 outbreak has caused adverse multifaceted effects on society but differently in women and men, thereby preventing the achievement of gender equality (the 5th sustainable development goal of the United Nations). According to a report by UN Women [14], the pandemic tends to lead women and girls to confront more severe challenges with respect to unpaid care, workload at home, unemployment, poverty, health, and domestic violence. Hence, it is important to make gender-based analyses on factors associated with undertaking responses to COVID-19 (e.g., telework). The findings may help to recognize gender gaps and formulate policy implications to reduce the gender inequality.

The mentioned-above background highlights the lack of literature and understanding about the difference between males and females in perceiving HBT and preferring more HBT and potential gender issues during the social distancing in developing countries. In this regard, this study, employing data from [13], aims to explore factors correlated to the perception and the preference for more HBT for male teleworkers versus female peers to analyze the gender inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic. The specific research questions are as follows:

- -

- How do male and female teleworkers perceive HBT during the social distancing and desire more HBT post-COVID-19?

- -

- Are factors affecting the perception of HBT for female teleworkers versus male teleworkers (during the social distancing) (dis)similar?

- -

- Are factors affecting the preference for more HBT for female teleworkers versus male teleworkers (post-COVID-19) (dis)similar?

- -

- Based on the gender-based findings on factors affecting the perception and the preference, how does gender inequality change in the social distancing?

This current analysis has extended the literature about HBT in a number of ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, it is one of the first studies providing new insights on factors associated with the perception of HBT during the COVID-19 era and the preference for more HBT post-COVID-19 given the gender. Second, it reports HBT-related knowledge from a developing country, where HBT was novel pre-COVID-19. Third, it highlights aspects of gender inequality in terms of adopting teleworking to respond to the pandemic. Fourth, it proposes implications for developing HBT sustainably, particularly with respect to gender equality.

The rest of this paper includes four sections. Section 2 synthesizes relevant studies on the practices of HBT and factors influencing HBT during the normal time and the COVID-19 period. Based on the review of Section 2, study design and analysis methods are determined and presented in Section 3. The next section comprises the main results of this research and discussions about factors associated with the perception and preference for HBT based on gender. Conclusions and study limitations suggesting future research directions close this paper.

2. Related Research on Telework in Normal and COVID-19 Times

2.1. Home-Based Telework during the Normal Time

The first concept of working far from a workplace (i.e., telecommuting) was introduced in the USA in the 1970s to handle transport-related issues such as traffic congestion and air pollution by reducing commuting between home and the workplace [15]. Due to the potential positive effects on urban transport, telecommuting is considered as a travel demand management strategy [16,17]. However, beyond transport-specific merits, telecommuting can bring about a host of multifaceted benefits for societies. Employees, owing to saving travel time and avoiding stress at the workplace, can gain greater working performances, higher job satisfaction, a better balance between work and life responsibilities, and more active transport [18,19,20,21]. In parallel, cities may face fewer congestions and less pollution, resulting from fewer vehicle kilometers traveled [22,23]. Over time, aspects of telecommuting have been intensively researched worldwide [24] and a wide range of alternative terminologies have been adopted, such as distance work, e-work, home-office, and remote work [25,26]. Among these terms, telework has been used the most frequently, particularly by researchers coming from Europe and Asia [27]. There is not a global definition of telework due to the existence of various places suitable for teleworking. Work in a satellite office refers to work undertaken in an office outside the enterprise’s headquarter. Mobile work is performed outside both home and the company’s main office but possibly at a client’s premises, on business trips, or fieldwork [28]. Informal work or mixed teleworking refers to working a few hours outside the company based on the negotiation between the employer and the employee for specific cases [29]. Although the locations of telework may vary, the most common place should be home [25] since the home in the modern world is acted as a communication hub that is well fit for doing e-activities [30]. In this current study, HBT is considered and defined as working from home by deploying information and communication technologies (ICTs) to keep in touch with colleagues and deal with allocated working tasks.

HBT is a relatively controversial phenomenon with mixed literature. While its advantages mentioned above are well-reported, the same is true for its disadvantages. Some of the obvious drawbacks of HBT are a decrease in the likelihood of professional advancement, significant professional isolation, new occupational diseases, and even an increase in travels, which challenges the HBT’s role in travel demand management, not to mention other issues arising from working in a number of contrasting locations [31,32,33]. Partially due to these disadvantages, the development of HBT varies across countries but is still below the expectations of its advocates [13,33,34]. To put it another way, researchers and practitioners are still seeking effective and efficient ways to deploy HBT within the context of the rapid advancement of ICTs.

In accordance with the research target stated above in Section 1, we searched for earlier studies on the perception and the preference for HBT. We found that there is only one account of research examining how perceptions of advantages and disadvantages of telework differ by gender [35] but no analysis on the perception of telework yet. By contrast, many previous authors have investigated determinants of the desire for teleworking (i.e., the preference for teleworking more) [36,37,38]. Females tend to have a more favorable opinion towards telework compared to males [38]; therefore, factors associated with the preference for HBT possibly differ across gender. The authors of [36,37] reported the insignificant roles of age and education in the attitude towards telework in the Netherlands and the UK. Whereas children in households are a strong determinant with a positive association with the preference [36,37,38]. The reason would be the escorting burden involved in the number/presence of children in families. Children are demonstrated as a main source of increasing work–family conflict and contribute to aggravating gender differences [17]. Notably, a contradictory result with respect to the effect of the commute distance was reported. While [38] demonstrated the home–work distance as a facilitator of the desire for teleworking, [23] emphasized the distance as a deterrent.

2.2. Home-Based Telework during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Prior to COVID-19, HBT is an informal working arrangement and needs a shock to make a breakthrough in its development process [25]. COVID-19 is the afore-said “shock” boosting the tremendous growth in telework, which is considered as a crucial strategy to mitigate the pandemic’s health-related and economic consequences.

As regards the views of experts, a worldwide survey, which was carried out from April to May 2020 to collect responses of 284 specialists in transport and other relevant fields, reported that 88.7% of participants recommended telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. The highest recommendation rates were seen for experts coming from the USA/Canada (100%) and Europe (98%) [39].

Regarding practical data, approximately 44% of workers either started working from home or teleworking more, which thereby resulted in 54% of all employees teleworking at least once per week during the pandemic in the Netherlands [10]. An observation in Istanbul (Turkey) reported 31% of respondents shifted to HBT [4]. A study carried out in Chicago [11] revealed a decrease in the rate of workers without experience in teleworking from 71% to 37% within the health crisis. Similarly, the Australian percentage of those with no day of teleworking dropped from 71% (pre-COVID-19) to 39% (in the COVID-19 period) [9]. The substantial declines in trip rates and vehicle-traveled kilometers in a host of cities worldwide have demonstrated the growth in HBT in that this working form altered the travel demand for working purpose [26,40,41,42,43,44]. Recent empirical evidence found that participants with higher durations of working from home were more inclined to spend less time on auto and transit [45]. In contrast to the boom in the adoption of teleworking in terms of quantity, the quality of HBT would be problematic because conducting HBT is a prompt response to an unprecedented situation without a contingency plan, according to a study of various companies of different sizes, different countries, and from different sectors [8].

Most earlier studies concerns about HBT as a part of comprehensive research on the travel mode use changes in connection with the implementation of safety measures [4,9,10,11]. Therefore, almost all findings are on descriptive statistics on the choice, the frequency, and the wish to further telework. However, there is a lack of in-depth reports on factors associated with the perception of HBT in the COVID-19 pandemic and the preference for HBT post-COVID-19. Only Nguyen [13] completely concentrated on factors affecting HBT to find that gender was a significant predictor of the perception and the preference for HBT with the case of Hanoi (Vietnam). In this sense, the ways of perceiving and desiring HBT for males and females would be dissimilar due to being influenced differently by factors.

Lyttelton et al. [46] explored the gender disparity in the context of working from home using data of 784 parents in the USA. They found that mothers implementing HBT declared more anxiety and loneliness with depressed feelings in comparison to fathers implementing HBT. This would stem from the fact that telecommuting mothers take heavier family responsibilities with more time spent on housework and childcare than telecommuting fathers. Such results would support a difference in the ways male and female teleworkers perceive HBT during the pandemic. In turn, the different perceptions may cause the gender-based difference in preferring to adopt HBT post-COVID-19.

In summary, to extend knowledge on HBT during and after the pandemic, there is a need to investigate factors associated with the perception and the preference for HBT based on gender.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Study Settings

Our study area was Hanoi, which is the second most populated city in Vietnam with about 7.32 million inhabitants. The Hanoi capital, similar to other megacities of emerging countries (e.g., Bangkok, Jakarta, Manila), has suffered from severe traffic congestion, accidents, and air pollution due to the dominant use of motorcycles and the low capacity of public transport [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56].

Once the study was designed and conducted (March and April 2020), the literature on factors associated with HBT during the pandemic was rare because European countries and the USA were on the first COVID-19 wave with social distancing and lockdown mandated. Therefore, understanding about factors governing the practice of HBT [8,57,58,59] was used to create a structured questionnaire including six sections as follows:

- The first part is a cover page describing the survey objectives and highlighting that this research only regarded workers who worked from home at least one weekday during the last week defined as seven preceding days. To give an illustration, in the case where a participant was interviewed on Wednesday, the period between yesterday (Tuesday) and Wednesday of last week was considered.

- The second part collected profiles of a respondent and his/her household, including age, gender, education of the respondent, his/her household monthly income, and the number of children. A child was defined as a person aged 0–11.

- The third part requested information on the type of company, the one-way home–work distance, and the company’s closure policy within the social distancing period. This section also asked for the participant’s past experience of using the internet and implementing telework or teleconference. Teleconference, which is defined as undertaking a live meeting of at least two participants at different places via telephone or network connection [27], was regarded since it, similar to telework, is a telecommunications-based working form.

- The fourth part contained attitudinal statements on HBT. Specifically, because workaholic and enjoyment in the workplace were found to be strong determinants of HBT [57], items in relation to such factors were modified and reused. The fear of human-to-human transmission of the coronavirus was measured by two questions while the views about HBT’s environmental benefits were surveyed by two items (see Table 2). As adopting HBT in Hanoi was nearly obligatory without preparation, teleworkers probably faced issues. As a result, we added two (yes/no) questions regarding difficulties in focusing on work and accessing data at home. Furthermore, the participant was requested to report the levels of (dis-)agreement with statements showing that (1) HBT was a good solution for the respondent in the social distancing period, and (2) HBT should be promoted and implemented coupled with working at a workplace in the respondent’s company post-COVID-19. Apart from two questions regarding difficulties, items in this section were measured by the five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree-strongly agree).

- The fifth and sixth sections encompassed online shopping-related questions and were not presented in detail as the emphasis of this paper is on telework.

3.2. Samples

Data collection was carried out over the four-week social distancing period, from 6 to 30 April 2020 (see Figure 1). During the pandemic with limited mobility, technological survey methods were widely performed [8,9,10,60,61]. This study, similar to previous research on COVID-19, carried out technology-enabled data collection using the snowball sampling technique with the convenience sampling method. Specifically, during the first two weeks, emails including questionnaires were sent to over 400 former students of the Faculty of Transport Economics at the University of Transport and Communications (UTC) (Hanoi, Vietnam). When a response was received, we composed and sent back to the respondent an email revealing our acknowledgment and a request to forward the questionnaire to other relevant candidates. Since 20 April, an online survey, created via the well-known Google Forms platform, was shared via a post on an author’s Facebook page. To attain wider coverage, this post was also shared with big (closed) groups on Facebook.

Eventually, we gathered 422 responses, 52 of which were provided by participants not living in Hanoi, and thus were eliminated. Fifteen incomplete surveys were disregarded. Among 355 respondents whose answers were eligible for further analyses, 134 sent their responses via email.

3.3. Methods

The study first analyzed the samples through descriptive statistics in accordance with gender. The Chi-square statistic was utilized to test the associations of gender with the perception (i.e., the levels of agreement with HBT being a good solution for the respondent in the social distancing period) and the preference for HBT (i.e., the levels of agreement with HBT being promoted and implemented coupled with working at the workplace in the respondent’s company post-COVID-19). Afterward, using the same method reported by the authors of [57], exploratory factor analysis was carried out to extract underlying factors from attitudinal statements. Subsequently, logit models were estimated to explore factors associated with the perception and the preference based on gender.

Depending on the way to treat the dependent variables (i.e., the perception and the preference), two types of modeling can be performed. If a dependent variable is considered as an ordinal variable with five values, ordered logit modeling can be estimated. Unfortunately, based on the results of the Brant test, ordered logit models executed for both males’ and females’ data violated the parallel regression assumption. Hence, the dependent variables were treated as binary variables. In case an answer was four (agree) or five (strongly agree), it was recoded to be one (yes/agree). Otherwise, the recoded value was zero (not yes/not agree).

Models 1 and 2 considered data of males and females, respectively. The dependent variable was the (binary) perception of HBT. The independent variables were age, educational level, monthly household income before COVID-19, the number of children, daily internet use before COVID-19, experience of adopting telework/teleconference, type of enterprise, enterprise’s closing policy, home–work distance, limited access to data, difficulty in focusing on work, response time, and factors found from attitudinal statements.

Models 3 and 4 considered data of males and females, respectively. The dependent variable was the (binary) preference for HBT. Compared with the independent variable list of Model 1, because the context of Models 3 and 4 was post-COVID-19, variables including experience of adopting telework/teleconference, limited access to data, difficulty in focusing on work, enterprise’s closing policy, and the attitudinal factor regarding fear of disease were excluded. Whereas, the perception, which is the dependent variable of Models 1 and 2, was considered.

All statistical analyses were undertaken using Stata 15.0 software. In the results of logit models, a p-value of smaller than 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

As can be seen in Table 1, for both the male and female samples, the most populous groups were the youngest with ages being between 20 and 30 (over 60%) while the eldest groups accounted for the smallest percentages (around 12%). The shares of graduate male and female respondents were similar at approximately 62%; however, a higher figure for those achieving a post-graduate degree was seen for females compared to males (28.1% vs. 21.5%). Regarding monthly household income, the percentage for the poorest female participants (20.8%) doubled the rate for the poorest male ones (10.2%) while an opposite relationship was seen for the 25–40-million-VND level. For the rest of the income levels, the shares for males and females were close together. In both datasets, more respondents lived in no-child households; yet the share for males (57.6%) was higher than that for females (46%). As regards the type of enterprise, 59.3% of male respondents were working at private companies while 28.3% were employed by state-owned ones. For the female dataset, by contrast, the difference in the rates for those working at private against state-owned companies was marginal (46.6% vs. 41.6%). The distribution based on company closure policies for females and males were similar. A quarter had to work from home while approximately half had a choice of either going to the workplace or not. More female participants than male peers (77% vs. 64.4%) did not have experience in adopting teleconference/teleworking before the COVID-19. The distributions of daily internet use time for males and females were close together with the vast majority of respondents being medium/heavy users. A higher percentage of females (68.5%) compared to males (59.3%) underwent limited access to data from home. Whereas the nearly equal shares of females and males (around 68%) had difficulty in concentrating on work at home. Most data for both datasets were gathered during the last three weeks. On average, male teleworkers traveled a longer distance to go to the workplace from home than female ones.

Table 1.

Breakdown of the samples.

As regards the perception, roughly 56% of females agreed that HBT was a good solution during the COVID-19 period while the percentage for males was only 45%. The analogous relationship is seen for the preference with 63% of female respondents supporting the further development of HBT post-COVID-19 compared to the figure for males being at 39%. The results of Chi-square tests confirm that gender has statistically significant associations with the perception (Pearson chi2 (1) = 4.2840; p = 0.038) and the preference (Pearson chi2 (1) = 20.3507; p = 0.000). Accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that female respondents were more positive about HBT during and after the COVID-19 than male peers (the authors would like to thank a reviewer for the note on using Chi-square test to examine the associations of gender with the perception and the preference).

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis Results

The results of exploratory factor analysis are presented in Table 2 wherein four factors, including pleasure at the workplace, workaholic, environmental benefit, and fear of disease were extracted from 10 attitudinal statements. The results of tests (KMO, Bartlett test of sphericity, and explained variation) demonstrated that the use of the exploratory factor analysis technique was appropriate, and factors found can represent attitudinal data reasonably.

Table 2.

Results of exploratory factor analysis.

4.3. Factors Associated with the Perception of HBT during the Social Distancing

Table 3 shows the results of Models 1 and 2 regarding the factors associated with the perception of HBT for males and females, respectively. Both models have goodness of fits within the range for pseudo-R2 recommended [62]. The factors can be divided into three groups, as follows.

Table 3.

Factors associated with the perception of HBT and the preference for more HBT based on gender.

Factors statistically affecting the perception only for male teleworkers: males whose households earned the highest income level (≥40 million VND) (OR = 0.093) were less likely to agree with HBT being a good choice. Frequently or regularly experiencing e-work pre-COVID-19 (OR = 5.100) was positively associated with the perception whereas difficulties in accessing data (OR = 0.229) and focusing on work (OR = 0.209) were deterrents.

Factors statistically affecting the perception only for female teleworkers: middle-aged female respondents (OR = 5.182) were more likely to show a positive perception of HBT than the youngest peers. Females living with at least two children (OR = 0.272) were less likely to have a good perception of HBT. In comparison with females mandatorily implementing HBT, those working at both the workplace and at home in accordance with the arrangement of companies (OR = 0.283) had a lower possibility of agreeing with HBT being a good adoption. Females surveyed within the fourth week of the survey (OR = 5.012) were more likely to have a good perception than those interviewed in the first week.

Factor statistically affecting the perception for both male and female teleworkers: fear of disease was the only significant variable for the perception of males (OR = 4.842) and females (OR = 4.511). The higher level of fear, the higher possibility of an agreement with HBT being good in the pandemic circumstance.

4.4. Factors Associated with the Preference for HBT Post-COVID-19

The results of Models 3 and 4 regarding the factors associated with the preference for HBT for males and females are presented in Table 3. Both models have overall goodness of fits within the range for pseudo-R2 typically achieved [62]. The factors can be categorized into three groups, as follows.

Factors statistically affecting the preference only for male teleworkers: males achieving graduate level (OR = 7.059) were more likely to desire HBT post-COVID-19 than those having no qualification or being an undergraduate. The positive perception of HBT (OR = 4.505) increased the possibility of preferring more HBT.

Factors statistically affecting the preference only for female teleworkers: age and children in a household were significant for the preference albeit with opposite effects compared to the perception. Specifically, middle-aged female teleworkers (OR = 0.190) were less likely to prefer further HBT than the youngest peers. A woman from a family with two or more children (OR = 5.026) was more interested in developing a hybrid working form after the successful control of the pandemic. The longer distance between home and the workplace (OR = 1.374) was involved in the higher likelihood of agreeing with triggering HBT post-COVID-19.

Factor statistically affecting the preference for both male and female teleworkers: attitudinal variables had the same effects on the preference for males and females. While pleasure at the workplace (OR = 0.294 for males and 0.223 for females) had a negative association, workaholic (OR = 2.464 for males and 2.636 for females) and environmental benefit (OR = 1.937 for males and 1.803 for females) had positive associations with the likelihood of agreeing with the further enhancement of HBT.

4.5. Discussion

The results shown in Section 4.1 wherein females were more inclined to have positive perception and preference for HBT than males are wholly consistent with the report of [13]. In addition, such findings confirm a more favorable opinion towards telework seen in females in the normal condition [38].

For males, factors associated with the perception of HBT were mainly involved in working. Specifically, difficulties in accessing data and concentrating on working reduced the likelihood of agreeing with HBT being a good solution. Regularly participating in telework/teleconference pre-COVID-19 encouraged a positive perception since males with previous experience can better adapt to HBT. Additionally, for a male, the highest level of income pertained to the lower likelihood of having a positive perception. This can be explained by the idea that a man is usually a breadwinner in a Vietnamese family [63]; therefore, a man from the highest household incomes would have a high salary and/or a high position in his company. During the social distancing time with HBT, business was disrupted, probably affecting considerably and negatively working achievements and income (According to [61], the rate of respondents with a decrease in family income during the COVID-19 time in Vietnam is about 70%.) Consequently, he did not perceive HBT positively.

For the female perception, the working variables mentioned above were insignificant whereas significant determinants were involved closely with family. During the social distancing period, children stayed at home due to the closure of their schools. Thus, mothers had to take heavier responsibilities for caring, even teaching children [64]. This probably led females to have a lower likelihood of gaining a positive perception. On the contrary, fathers may not encounter this problem seriously, thus having greater than one child in a household was not a predictor of the male perception. Middle-aged female teleworkers were less likely to consider HBT being good because the household burden on them tends to be heavier than that on the younger group. To give an illustration, the 31–45-year-old group usually relates to the process of reproduction, caring for small children, and even caring for old parents, whereas household duties for younger women, who tend to be single and have younger parents, would be smaller. Compared to exclusively working at home, working both at home and in the workplace based on the company’s arrangement had a negative association with the perception possibly since women would like more time to look after their families. Notably, based on the result of response time, it seemed that women found a way to better deal with and adapt to increased family responsibilities over time, thereby leading them to have the higher likelihood of achieving a positive perception in the last week of this survey.

For both males and females, the fear of disease was the major motivation for perceiving HBT positively. This result was understandable since HBT is a protection measure during the pandemic period.

The findings on factors associated with the perception highlight that the family responsibilities for females, typically represented by caring children, seemed considerably heavier, thereby influencing negatively their perception. Males, meanwhile, would not be affected much by family duties because they focused mainly on working issues. The support of males given to females regarding household chores may increase [65]; however, it would be small compared with the increasing levels of family tasks during the social distancing time. In this sense, this study confirms the unbalanced reorganization of care against women during the COVID-19 era [64], thereby inducing the increased gender inequality.

As regards the preference for HBT post-COVID-19, males without a qualification or that were an undergraduate usually had jobs/positions inappropriate for teleworking (e.g., blue-collar workers). Therefore, they were less likely to show a preference for further HBT. While the perception of HBT had a positive association with the preference for further HBT for males, the same was not true for females, for whom age and children in their household were determinants. Middle-aged female teleworkers were more likely to have a positive perception but less likely to have a positive preference. The possible explanation is that females aged 31–45, after a period of working from a younger age, would like to demonstrate their competence, attain career promotion, and higher salary; however, HBT is claimed as a possible reason for fewer opportunities for career promotion [66] and salary growth [67]. Children were a source of distraction when staying at home for female teleworkers; thus, being a negative factor of the perception. Nevertheless, the burden of looking after and satisfying their demand (e.g., chauffeuring), with which mothers usually are charged in their families [68], leads females to support the further development of HBT post-COVID-19. The longer the commute distance the higher likelihood for females of agreeing with the promotion of HBT, possibly because female teleworkers usually took account of combining the routes to the workplace and to their children’s schools. This finding was in line with the conclusion that women, because of their dual roles of wage earner/homemaker, are more sensitive to home-work distance than men [69]. Another possible reason could be that compared with men, women tend to put more focus on risks (e.g., traffic, environmental hazards) [70] that may increase with the home-work distance.

The effects of attitudinal factors (pleasure at workplace, workaholic, and environmental benefits) on the preference for further HBT were the same for both female and male teleworkers. Both males and females appreciated the environmental benefits of HBT as the air quality in Hanoi improved vastly during the social distancing period [71].

The results of factors correlated to the preference show that for females, the perception of teleworking would not be important for the desire for more HBT. Instead of this, they consider the benefits of teleworking, including having flexible working time to balance work and family tasks, avoiding long commute distances, and reducing exposure to pollution. This highlights the female concern about seeking a measure to deal with their burden, which existed pre-COVID-19. Males, by contrast, probably owing to not being under the same pressure as females, take account of the perception of HBT and working-related attitudes (i.e., workaholic and pleasure at the workplace).

Using the same dataset as this study, [13] provides the general knowledge on factors governing the perception and the preference for HBT but does not show clearly the difference in how these factors affect the attitudes of males compared to females. For example, living with two children increases the likelihood of supporting further HBT post-COVID-19 for teleworkers [13]; yet, this current analysis has found that the above-mentioned children-related finding is true only for female teleworkers but not for male counterparts. This study, therefore, has extended the understanding of the perception, the preference for HBT, and their influential factors during the COVID-19 era.

Based on the discussed-above findings, some brief implications could be derived from this research as follows. First, women once working from home take more household responsibilities, which demonstrates the important role of women in dealing with the aftermath of the pandemic and helping their relatives (e.g., children and husbands) to do so. Unfortunately, females may have a poor experience with HBT due to the increased household-related burden. Hence, it is important to have a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of COVID-19 on women with a focus on psychological pain. Second, females, no matter how they perceived HBT during social distancing, would still believe that HBT is a potential strategy to balance work and family duties. Thus, after COVID-19 is controlled successfully, telework can be enhanced by encouraging female employees to (re-)adopt first. Third, within the following waves of COVID-19 or within the next pandemic period, besides implementing strict non-pharmaceutical interventions, programs supporting women, particularly during the process of HBT, should be considered to be formulated timely and effectively. Fourth, for promoting telework post-COVID-19, the environmental benefits of working at home should be highlighted. All previously mentioned implications and findings would be informative for preparing effective strategies and appropriate responses to mitigate the negative effects of COVID-19 on citizens, especially women in Vietnam and other emerging countries.

5. Conclusions

Physical distancing and lockdown are essential to suppress the spread of COVID-19. Nevertheless, to avoid freezing the economic activities, HBT has been widely adopted in Hanoi. By analyzing data of teleworkers in the first nationwide social distancing period, this study provides useful insights into gender-based differences in perceiving and preferring HBT coupled with influential factors. Higher rates of females compared with males had a positive perception of HBT within the social distancing period and a desire to telework more post-COVID-19. Findings on influential factors highlight the increased disproportion of allocating household responsibilities between males and females within the social distancing time. When COVID-19 ends, females would consider HBT as a solution to solve the burden existing pre-COVID-19 and increasing in COVID-19. Considering gender inequality is necessary for the government and authorities to lessen the adverse effects of COVID-19 on the lives of citizens, especially females, in developing countries.

This research is one of the first studies providing gender-based understandings about factors affecting the perception and the preference for HBT during the era of COVID-19 in a developing country. The interpretation of the findings, however, should consider several limitations. The first is the self-selection bias and the high homogeneity of data used. Specifically, the samples were not representative of the teleworker population in Hanoi because data collection was implemented using emails, a web-based questionnaire, and Facebook together with the snowball sampling technique. Participants having email addresses and/or access to the internet were over-represented. Besides, there would be a bias toward former students of UTC. The homogeneity would come from some companies because an employee may share the online questionnaire with his/her colleagues or co-workers. Due to the bias, the generalization of the findings of this study would be weak to some extent. However, it is important to note that during the era of mobility circumscription, employing technology-based survey methods seemed to be the most appropriate [61]. Second, this research ignored some potential independent variables (e.g., jobs and living area) to make the questionnaire short enough to achieve a high response rate. Third, this analysis is limited to the short run while the pandemic is ongoing unprecedentedly. Therefore, continuing to track the development of HBT for male and female workers would be interesting. Subsequent research should design the recruitment better to achieve a representative sample, thereby allowing for the obtaining of more generalizable findings. Equally important would be to carry out further gender-based analyses in different areas because the scales of COVID-19 vary across regions of a country and among countries. For future studies, the findings of this study could be a good reference.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.N. and J.A.; methodology, M.H.N.; formal analysis, M.H.N. and J.A.; investigation, M.H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.N.; writing—review and editing, M.H.N. and J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give many thanks to (1) the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, (2) volunteer respondents in Hanoi, (3) our colleagues at UTC, Thi Thuy Linh NGUYEN (KNA Cert), Huy Nghia NGUYEN (Viet Star Company) for their kind support regarding the collection of telework-related data, (4) our students at UTC—Campus in Ho Chi Minh city (Thanh Nguyen DO, Thi My Dinh DANG, Thi Phuong Thanh PHAM, Thi Bich Ngoc NGUYEN, Thi Thuy Vy VO, and Kim Nguyen NGUYEN) for their kind support regarding the collection of COVID-19 data in Vietnam, and (5) Quang-Huy NGUYEN (Department of Computational Biomedicine, Vingroup Big Data Institute, Hanoi, Vietnam) for useful statistical advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pradhan, D.; Biswasroy, P.; Kumar Naik, P.; Ghosh, G.; Rath, G. A Review of Current Interventions for COVID-19 Prevention. Arch. Med Res. 2020, 51, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, D.; Shahin, M.; Dias, C.; Abdullah, M. Role of Transport during Outbreak of Infectious Diseases: Evidence from the Past. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard Medical School Treatments for COVID-19. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/treatments-for-covid-19 (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Shakibaei, S.; de Jong, G.C.; Alpkökin, P.; Rashidi, T.H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Travel Behavior in Istanbul: A Panel Data Analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The Effect of COVID-19 and Subsequent Social Distancing on Travel Behavior. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.T.; Hoang, T.D.; Tran, V.T.; Vu, C.T.; Fodjo, J.N.S.; Colebunders, R.; Dunne, M.P.; Vo, T.V. Preventive Behavior of Vietnamese People in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S.J. Information Management Research and Practice in the Post-COVID-19 World. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the Context of the Covid-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.J.; Hensher, D.A.; Wei, E. Slowly Coming out of COVID-19 Restrictions in Australia: Implications for Working from Home and Commuting Trips by Car and Public Transport. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 88, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haas, M.; Faber, R.; Hamersma, M. How COVID-19 and the Dutch ‘Intelligent Lockdown’ Change Activities, Work and Travel Behaviour: Evidence from Longitudinal Data in the Netherlands. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 6, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiripour, A.; Rahimi, E.; Shabanpour, R.; Mohammadian, A.K. How Is COVID-19 Reshaping Activity-Travel Behavior? Evidence from a Comprehensive Survey in Chicago. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNN. How Vietnam Managed to Keep Its Coronavirus Death Toll at Zero. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/05/29/asia/coronavirus-vietnam-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Nguyen, M.H. Factors Influencing Home-Based Telework in Hanoi (Vietnam) during and after the COVID-19 Era. Transportation 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. From Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Nilles, J.M. Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff: Options for Tomorrow; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1976; ISBN 9780471015079. [Google Scholar]

- De Abreu e Silva, J.; Melo, P.C. Home Telework, Travel Behavior, and Land-Use Patterns: A Path Analysis of British Single-Worker Households. J. Transp. Land Use 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Moeckel, R.; Moreno, A.T.; Shuai, B.; Gao, J. A Work-Life Conflict Perspective on Telework. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 141, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elldér, E. Telework and Daily Travel: New Evidence from Sweden. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 86, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, J.; Smart, M.J. Working at Home and Elsewhere: Daily Work Location, Telework, and Travel among United States Knowledge Workers. Transportation 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A Review of Telework Research: Findings, New Directions, and Lessons for the Study of Modern Work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.; Craig, L. Gender Differences in Working at Home and Time Use Patterns: Evidence from Australia. Work Employ. Soc. 2015, 29, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendyala, R.M.; Goulias, K.G.; Kitamura, R. Impact of Telecommuting on Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Household Travel. Transportation 1991, 18, 383–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, V.; Ristimäki, M. Relationships between Commuting Distance, Frequency and Telework in Finland. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Cobo, M.J. What Is the Future of Work? A Science Mapping Analysis. Eur. Manag. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, A.; Lethiais, V.; Rallet, A.; Proulhac, L. Home-Based Telework in France: Characteristics, Barriers and Perspectives. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, J.; Schatzmann, T.; Schoeman, B.; Tchervenkov, C.; Hintermann, B.; Axhausen, K.W. Observed Impacts of the Covid-19 First Wave on Travel Behaviour in Switzerland Based on a Large GPS Panel. Transp. Policy 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, P.; Salomon, I.; Pliskin, N. Review: State of Teleactivities. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2010, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, S.R. The Effects of Home-Based Teleworking on Work-Family Conflict. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2003, 14, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, J.H. Home Teleworking: A Study of Its Pioneers. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1984, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, R.; Gripsrud, M. Home as a Communication Hub: The Domestic Use of ICT. J. Transp. Geogr. 2009, 17, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, E.D.V.; Motte-Baumvol, B.; Chevallier, L.B.; Bonin, O. Does Working from Home Reduce CO2 Emissions? An Analysis of Travel Patterns as Dictated by Workplaces. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, F.; Santos, E.; Diogo, A.; Ratten, V. Teleworking in Portuguese Communities during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, A. Rapid Change or Slow Evolution? Changing Places of Work and Their Consequences in the UK. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who Is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarian, P.L.; Bagley, M.N.; Hulse, L.; Salomon, I. The Influence of Gender and Occupation on Individual Perceptions of Telecommuting. In Women’s Travel Issues Second National Conference Drachman Institute of the University of Arizona; Morgan State University; Federal Highway Administration: Baltimore, MD, USA, October 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, H.; Lyons, G.; Chatterjee, K. An Examination of Determinants Influencing the Desire for and Frequency of Part-Day and Whole-Day Homeworking. J. Transp. Geogr. 2009, 17, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, P.; Tijdens, K.G.; Wetzels, C. Employees’ Opportunities, Preferences, and Practices in Telecommuting Adoption. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iscan, O.F.; Naktiyok, A. Attitudes towards Telecommuting: The Turkish Case. J. Inf. Technol. 2005, 20, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Frank, L.D. COVID-19 and Transport: Findings from a World-Wide Expert Survey. Transp. Policy 2021, 103, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucsky, P. Modal Share Changes Due to COVID-19: The Case of Budapest. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenelius, E.; Cebecauer, M. Impacts of COVID-19 on Public Transport Ridership in Sweden: Analysis of Ticket Validations, Sales and Passenger Counts. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Best Practice in City Public Transport Authorities’ Responses to COVID-19: A Note for Municipalities in Bulgaria; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Orro, A.; Novales, M.; Monteagudo, Á.; Pérez-López, J.-B.; Bugarín, M.R. Impact on City Bus Transit Services of the COVID–19 Lockdown and Return to the New Normal: The Case of A Coruña (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, C.; Nobis, C.; Kolarova, V.; Lenz, B.; Winkler, C. Transport Mode Use during the COVID-19 Lockdown Period in Germany: The Car Became More Important, Public Transport Lost Ground. Transp. Policy 2021, 103, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbilen, B.; Wang, K.; Akar, G. Revisiting the Impacts of Virtual Mobility on Travel Behavior: An Exploration of Daily Travel Time Expenditures. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyttelton, T.; Zang, E.; Musick, K. Gender Differences in Telecommuting and Implications for Inequality at Home and Work; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Ha, T.T.; Tu, S.S.; Nguyen, T.C. Impediments to the Bus Rapid Transit Implementation in Developing Countries—A Typical Evidence from Hanoi. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2019, 4, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Pojani, D. Why do some BRT Systems in the global south fail to perform or expand? In Preparing for the New Era of Transport Policies: Learning from Experience; Shiftan, Y., Kamargianni, M., Eds.; Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Elsevier Academic Press: Cambridge, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 35–61. ISBN 9780128152942. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, D. Making Megacities in Asia: Comparing National Economic Development Trajectories. Springer Briefs in Regional Science; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 9789811506598. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Armoogum, J. Hierarchical Process of Travel Mode Imputation from GPS Data in a Motorcycle-Dependent Area. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 21, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H. Evaluating the Service Quality of the First Bus Rapid Transit Corridor in Hanoi City and Policy Implications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovations for Sustainable and Responsible Mining; Tien Bui, D., Tran, H.T., Bui, X.-N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 98–123. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q.; De Gruyter, C.; Nguyen, H.A.; Nguyen, T.; Ngoc Su, D. Risky Behaviours Associated with Traffic Crashes among App-Based Motorcycle Taxi Drivers in Vietnam. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 70, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Armoogum, J.; Adell, E. Feature Selection for Enhancing Purpose Imputation Using Global Positioning System Data without Geographic Information System Data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Tu, S.S.; Nguyen, M.H. Evaluating the Maiden BRT Corridors in Vietnam. Transp. Commun. Sci. J. 2020, 71, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, L.T.; Tay, R.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Relationships between Body Mass Index and Self-Reported Motorcycle Crashes in Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Pojani, D. The Urban Transport Crisis in Emerging Economies: A Comparative Overview. In The Urban Transport Crisis in Emerging Economies; Pojani, D., Stead, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 283–295. ISBN 9783319438498. [Google Scholar]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Wang, B. Factors Associated with Home-Based e-Working and e-Shopping in Nanjing, China. Transportation 2018, 45, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.-R. Interpreting Employee Telecommuting Adoption: An Economics Perspective. Transportation 2000, 27, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannering, J.S.; Mokhtarian, P.L. Modeling the Choice of Telecommuting Frequency in California: An Exploratory Analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 1995, 49, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipe, N.G. Cars Rule as Coronavirus Shakes up Travel Trends in Our Cities. Available online: http://theconversation.com/cars-rule-as-coronavirus-shakes-up-travel-trends-in-our-cities-142175 (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Tran, B.X.; Nguyen, H.T.; Le, H.T.; Latkin, C.A.; Pham, H.Q.; Vu, L.G.; Le, X.T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, Q.T.; Ta, N.T.K.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Economic Well-Being and Quality of Life of the Vietnamese During the National Social Distancing. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.M.; Greene, W.H. Applied Choice Analysis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781107092648. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, L.A. Gender Identity and Agency in Migration Decision-Making: Evidence from Vietnam. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2011, 37, 1441–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.K.C.; Minello, A. Mothers, Child care Duties, and Remote Working under COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy: Cultivating Communities of Care. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K.; Scheibling, C.; Milkie, M.A. The Division of Domestic Labor before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada: Stagnation versus Shifts in Fathers’ Contributions. Can. Rev. Sociol. Rev. Can. De Sociol. 2020, 57, 523–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlmann, M. Social aspects of telework: Facts, hopes, fears, ideas. In Telework: Present Situation and Future Developments of a New Form of Work Organization; Korte, W.B., Robinson, S., Steinle, W.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Golden, T.; Eddleston, K.A.; Powell, G.N. The Impact of Teleworking on Career Success: A Signaling-Based View. Proceedings 2017, 2017, 14757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motte-Baumvol, B.; Bonin, O.; Belton-Chevallier, L. Who Escort Children: Mum or Dad? Exploring Gender Differences in Escorting Mobility among Parisian Dual-Earner Couples. Transportation 2017, 44, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Johnston, I. Gender Differences in Work-Trip Length: Explanations and Implications. Urban Geogr. 2013, 6, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.Y.; Sharma, P.; Adithipyangkul, P.; Hosie, P. Gender Equity and Public Health Outcomes: The COVID-19 Experience. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Urrego, D.; Rodríguez-Urrego, L. Air Quality during the COVID-19: PM2.5 Analysis in the 50 Most Polluted Capital Cities in the World. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).