Abstract

The rise of Asian and the stagnation of Western middle classes over the last thirty years have resulted in gradual convergence of income of large parts of the world’s population. Recent global crises—the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic—have led to a decline in income and increase in income uncertainty. Rise in consumption of lower quality goods of shorter durability and an overall decline in demand and economic activity resulted as challenges to the global economy. In this paper, we argue that generational responsibility in consumption can be an environmentally sustainable response to crises which enables the economies to overcome the crisis of confidence and reaffirms community ties. As an element of long-term orientation in consumption, generational responsibility is a cultural phenomenon dependent on solidarity within family and the wider community. It is characterized by consideration of consequences of consumption choices on the environment, and the abundance of savings and the usability of goods to be inherited by future generations. For companies, willing to revisit their traditional business models and incorporate principles of sustainability in their competitive strategies, promotion of generational responsibility can become a new source of competitive advantage and a driver of economic recovery.

1. Introduction

Globalization has been accelerating in the last three decades, resulting in growing connectedness between people, companies, and national states. This process has changed many social, cultural, economic, and political aspects of the world. While globalization has created plentiful business opportunities and boosted economic growth, the growth has varied across national economies. Moreover, not all groups of consumers within nations have experienced the same benefits from globalization, resulting in growing inequality. The biggest losers of this period were members of the Western middle class, whose growth of real income over the last three decades was negligible [1,2]. In combination with the 2008 and 2020 crises, this resulted in a partial loss of trust in public institutions and sporadic outbursts of social unrest that followed austerity policies in some European countries [3], increasing the uncertainty about the economic future.

Over the same period, the Asian middle class and one percent of the richest world population experienced considerable growth of real income, while the Asian middle class also grew in absolute size and as a share of the total Asian population [1,2,4,5]. This resulted in part because of outsourcing of production into emerging markets and the higher profits which this generated, respectively. The growth of the Asian middle class was accompanied by rising consumption which speeded up resource depletion and environmental devastation. Because environmental problems started to hinder economic development and lower the quality of life, sustainability and corporate social responsibility are not any more merely marketing tools [6] but have become approaches that can significantly affect corporate competitiveness [7].

Contemporary economic context is characterized by yet another set of problems. Not in the least because of growing interconnectedness of national economies, several economic crises of the last three decades—the Asian Crisis, Dot-com bubble, the Great Recession, and the COVID-19 Recession—had a global reach and consequences. The COVID-19 crisis, caused by an infectious disease, moreover directly affected and challenged the strength of community ties. Individuals have experienced great economic uncertainty, feeling that neither communities nor public institutions, in spite of the fiscal stimuli, are able to provide adequate support and restore a feeling of confidence in the economic future [8]. Any contribution to resolving the aforementioned economic, environmental, and social problems of the modern world would therefore be important for individual, communities, companies, and governments.

In this paper, we attempt to make such a contribution. Our goal is to construct a sustainable and marked-based solution that would address the stated challenges of the modern times. To do that, we take a holistic approach whereby we combine insights from the theory and empirics of several disciplines—economics, history, philosophy, management, and marketing. In particular, we construct a solution that would be built on the workings of a market mechanism—one that would rely on insights from the economic, management, and marketing theory and practice. Moreover, we propose a novel driver of such a market mechanism that is based on aspirations and values of individuals and communities. This driver is the concept of generational responsibility in consumption which we introduce and argue that this concept could allow us to simultaneously address the aforementioned economic, environmental, and social problems of the modern world. Generationally responsible consumption is characterized by consumption decisions that consider not only individual but also the economic and social wellbeing of the future generations of the community to which the individual perceives himself as belonging. We argue that our consumption model could serve as an environmentally sustainable response to crises. We also explain how it could enable the economies to overcome the current crisis of confidence and restart economic growth, as well as help societies to reaffirm community ties. Based on the insights from several disciplines, we present arguments why our model should be expected to effectively lead to the improvement of the economic, environmental, and social context, resulting from a virtuous circle of changes initiated by generationally responsible consumption. At the same time, we acknowledge that the complexity of transformations that generationally responsible consumption would initiate limits our ability to empirically test the speed and reach of the resulting changes.

Our work relates to papers that analyze consumers’ sustainable consumption [9,10] and changing customer preferences during economic crises [11]. By including inter-generational relationships and community ties in our analysis, we extend these studies. Besides that, our model shows that the economic context in which consumption decisions are taken greatly affects what one could consider as generationally responsible consumption. We also build on the work that studies the differences in characteristics of different cultures [12], and their influence on sustainable consumption [13,14,15,16,17]. Our paper is different in at least two respects. Firstly, we interact several cultural characteristics to derive a novel generationally responsible consumption model and study its effect both on sustainable consumption and consumption that benefits the future generations. Secondly, we study how our consumption model interacts with the economic context and how it could improve this context. This paper also contributes to the plentiful literature struggling to efficiently incorporate principles of sustainability in competitive strategies [18,19,20]. Our paper extends previous studies, connecting them with consumption context, consumers’ attitudes toward sustainability, generational altruism, and management concepts of ambidexterity and disruptive innovations. Including more determinants in our analysis, we are able to highlight how companies integrate principles of sustainability in their business models in a different economic and cultural context. Taking a multidisciplinary approach enables us to examine the concept of generational responsibility in consumption from different economic, management, and marketing perspectives. Our work also relates to the papers that study the role of social and political factors, and economic expectations, on the dynamics of crises [21,22]. De Long and Eichengreen [21] argued how a consensus on sharing the gains from economic growth, resulting from balance of power of different economic classes, resulted in high growth rates during the European post-WWII recovery. In a different political and economic context, we present a consumption model that should allow the Western middle and lower classes to themselves, in the current moment, initiate higher economic growth and a more equitable distribution of its gains.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature. In Section 3, we present our research question, hypothesis, and the method used. In the following section, we examine the role of communities in the course of major economic crises and transitions of the past century. In Section 5, we explain the concept of generational responsibility in consumption, and examine its characteristics in the context of a prominent categorization of cultural characteristics used in management studies. In Section 6, we draw on the insights from the past of economic crises and cultural characteristics of societies to demonstrate how generationally responsible consumption could be an environmentally friendly and community building response to crises. We do so by discussing how generational responsibility in consumption could be used by both the demand and the supply side—by consumers and by companies—to drive the post-crisis recovery. In doing so, we highlight the ways in which companies could learn, or emerge to serve, the generationally responsible market segment. Section 7 presents the interpretation of our findings and graphically summarizes the workings of the market-based method which we construct and which is driven by generational responsibility in consumption. It also lists the limitations of our study and compares our results to those of the existing studies, highlighting their implications in the context of the current economic environment. The final section concludes.

2. Review of Related Literature

This paper relates to the literature on sustainability in consumption and sustainability of business models. The newly created business environment has encouraged companies to apply the triple bottom approach—economic, environmental, and social—in the creation and execution of business strategies. Sustainability is one of the most important megatrends and many companies issue sustainability reports and create a methodology to measure triple bottom line performances [23]. This trend is accelerated by the development of stakeholder theory which argues that the role of companies is to fulfill the goals of internal and external stakeholders [24] even though some of the stakeholders’ goals are confronted [25]. Proponents of the theory state that all stakeholders and their goals are equally important for companies, but they neglect the fact that customers can also be employees or be in the role of other stakeholders at the same time. For this reason, consumers’ behavior, directly and indirectly, can influence the fulfillment of other stakeholders’ goals in the long run, and sustainable consumption is the cornerstone of sustainable business models and the sustainability of economic development.

Our paper is related to prominent papers [9,10] that analyze sustainable consumption. We extend these studies in several ways. These authors consider overconsumption as the main factor which causes environmental, economic, and social problems, and propose consumers’ self-control as the key way to achieve triple bottom line goals. On the other hand, our model does not propose to cut consumption, but to change consumers’ preferences to achieve these goals. Secondly, the studies consider that intergenerational altruism could only contribute to future generations through achievement of environmental goals. Different from this, we consider generational responsibility in consumption as the main concept which can result in both material and immaterial benefits for the future generations. Thirdly, the previous consumption models are static, while we believe that sustainable consumption depends on the economic and cultural context, and that it is changing with this context. Finally, Sheth, Sethia, and Srinivas [9] argue that companies have to change only the marketing mix to adapt to new consumers’ preferences, while we believe that this would not be sufficient to gain a competitive advantage. We extend their analysis and argue that the companies have to change their competitive strategies, become ambidexter, and be able to create disruptive innovations to deal with the new market reality.

Sustainable consumption as a research area evolved from ethics in consumption to a more holistic approach which includes the influence of consumption on the environment and wellbeing of future generations. The diffusion and acceptance of the idea of sustainable consumption has been promoted by national governments and Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and consumers’ attitudes toward sustainable consumption are positively correlated with their level of education [26,27] and with economic conditions [28]. Rapoport and Vidal [28] argue that intergenerational altruism in consumption is driven by nature in less developed countries—up to the level when individuals have satisfied their physiological constraints—while such behavior in developed countries is mainly driven by the level of consumers’ discretionary income and their altruistic preferences.

More broadly, our paper belongs to the literature on ethical consumption which has been the focus of researchers already for a couple of decades. Vittel and Muncy are pioneers in this field of research. They analyzed how consumer ethics influence consumer behavior and preferences. To measure the influence of consumer ethics on consumption, they designed a consumer ethics scale, which consists of four dimensions: (a) actively benefiting from illegal activities (active), (b) passively benefiting (passive), (c) actively benefiting from deceptive (or questionable, but legal) practices (legal), and (d) no harm/no foul activities (no harm) [29]. The scale has been widely accepted in research, but due to changes in the business environment, Muncy and Vittell upgraded the scale with three additional determinants: 1. downloading/buying counterfeit goods; 2. recycling/environmental awareness and, 3. doing the right thing/doing good [30]. Muncy and Vitell [30] concluded that consumers’ ethical behavior is strongly connected with their environmental awareness and their readiness to participate in activities after consumption (i.e., recycling). Consumers’ attitude toward ethical consumption, which results in the preservation of resources for the future generations, depends on the consumption context. Contextual factors can encourage or discourage consumers to behave ethically in consumption [31]. Different theories analyze the influence of different contextual factors like religion [14,32,33,34,35,36], national cultures, governmental, and non-governmental support for sustainable consumption, degree of economic development, and others.

The influence of national cultures on ethical consumption has been thoroughly analyzed. Hofstede’s determinants of national cultures have been used frequently in previous studies to identify how national cultures affect different aspects of ethical consumption [13]. To analyze the influence of consumers’ long-term orientation on their ethical behavior, researchers use two dimensions of long-term orientations: focus on long term objectives and valuation of tradition. Previous studies revealed that long-term orientation is positively correlated with consumers’ ethical consumption [14,15,16,17]. In collectivistic cultures, individual identity is derived from his or her collective group (for example family, local community, or company). In this type of culture, group members express loyalty to the group, while their group provides different types of support and social services to its members. Previous studies find out that collectivistic consumers behave more ethically in consumption than individually oriented consumers [37,38,39]. Collectivistic consumers’ identification with own groups is high, so when they make consumption decisions, they try to balance their own interests and group interests. Due to that, relationships with older community members and towards children affect their attitudes toward sustainable consumption [40,41]. Additionally, groups encourage consumers to build positive attitudes toward sustainable consumption [42]. In our paper, we relate to this literature by interacting several cultural characteristics, previously typically studied at the national level, to propose a novel generationally responsible consumption model. We also show how the application of such a consumption model would depend on the economic context and how it could in return influence the economic context.

In proposing an environmentally sustainable response to crises of the economy and the environment, our paper also relates to the literature on overconsumption. Buying more goods than you need has been identified as one of the most important factors which result in environmental devastation [9]. World Bank data revealed that in the last 30 years, the United States has experienced a drop of gross domestic savings to GDP ratio, while in the same period, final consumption to GDP ratio has been growing [43]. Overconsumption results in lower savings and consequently in lower investments, depletion of resources, and inefficient use of property. Overconsumption is frequently a consequence of the materialistic attitudes of consumers. Possession of material goods increases the happiness of materialistic consumers. Some studies find negative influence of materialism on ethics in consumptions [32,44] while other studies argue that materialism affects only some dimensions of consumers’ ethics [35,36]. Non-governmental organizations try to educate and encourage consumers, especially in developed countries, to be less materialistic, become more frugal and long term oriented, and to enhance their self-control. These activities can only boost the sustainable consumption of materialistic consumers who consider material goods as a source of happiness. On the other hand, these activities cannot influence the behavior of consumers who consider material goods as a tool to express their happiness to society [45]. We believe that our generationally responsible consumption model can be acceptable for the first group of materialistic consumers because we argue that they could increase their happiness with fewer material goods.

Our paper also relates to the literature on consumption in crises. Global crises make contemporary economic and business models obsolete and significantly change consumption context. They result in a drop in consumers’ income, growing unemployment, and rising uncertainty, which force consumers to change priorities in consumption and life. During crises, consumers lower spending and embrace frugal products [46]. At the beginning of crises, consumers increase spending on basic products and cut discretionary spending. Consumers demand simplicity and insist on ethical business governance during crises, which influence their ethics in consumption [11,47]. Consumer attitudes toward sustainable products are affected by a significant number of factors such as price, quality, and consumption comfort. Crises change the influence of individual factors and consumers are balancing their importance in a new context [48].

In proposing ways in which companies can use the concept of generational responsibility in consumption to successfully overcome the current crisis of consumer confidence, this paper relates to the literature on corporate strategies and sustainability. Our paper contributes to the previous vibrant discussion about sustainability and contemporary business [18,19,20]. These studies found that companies’ activities are considered as the main reasons for growing social, environmental, and economic problems. Due to that, the authors argue that companies have the main responsibility to be a driver of sustainable practices, and that by incorporation of principles of sustainability in competitive strategies, they could contribute to the achievement of both their business and some sustainability goals. On the other hand, we believe that all sustainability goals could be achieved simultaneously if consumers were to behave generationally responsibly, and companies would have to adapt their business models to the new consumption model. Porter and Kramer [18] consider development of local business clusters, made of supporting companies and infrastructure, as the key way to create shared wealth for companies and consumers. We added informal communities, such as the family, into our analysis as a factor that could contribute to the achievement of sustainability goals. Finally, the authors do not include economic and cultural characteristics in their analysis, which we do.

Crises and new customer preferences force companies to reconsider their business models and find new ways to achieve a competitive advantage. Declining demand and rising consumers’ frugality motivate companies to adjust product portfolio and focus on good enough products [49]. During crises, consumers are looking for safety, thus companies should include motives related to family in their advertisements. Companies have to cut costs, but they should find a way to preserve investments in sustainable solutions [50,51] because sustainability is a trend that will determine their competitiveness in the future. Sustainability encourages companies to invest in disruptive innovations during crises [52]. Disruptive innovations result in lower prices, higher quality, and increased functionality [53]. They positively impact the environment and the interests of future generations. High acceptance of the innovations necessary to serve the generationally responsible market segment following the current crisis could also counter the decline in innovative activities documented by Kočović, Kočović, and Jovović [54] as following the Great Recession, even without a strong support by the government. Companies that achieve to integrate sustainability into their business models are likely to survive crises, build stronger brands, and create a competitive advantage [18,19,20].

Our paper finally builds on the literature on the role of communities in preserving cultural heritage and their role in the dynamics of crises. Kočović and Đukić [55] emphasize the importance of participatory governance and local community involvement in managing questions related to cultural heritage, and suggests that even consumer preferences can affect the transmission of communal culture across generations. Our paper analyzes environmental and economic crises jointly, such as in Malović [56], and proposes integral solutions for them. De Long and Eichengreen explain how the social and political factors in post-WWII Europe resulted in a consensus of different economic classes on how to share the gains from economic growth [21]. They argue that the consensus was helped by the funds of the Marshall Plan and was based on a balance of political power between economic classes. This led to a partial liberalization of post-war European economies which enabled high growth rates that lasted for quarter a century. In the present economic and political context, the incomes of the Western middle classes are stagnating for thirty years and their political power is lower relative to the upper classes than before. We therefore propose a novel consumption model, generational responsibility in consumption, and argue that it could help Western middle and lower classes to themselves initiate higher economic growth in their societies and acquire a higher share of the gains it would bring. Romer [57] and Eggertson [22] emphasize the role of expectations about the economic future on the dynamics of crises. Just like the economic uncertainty broke the confidence of consumers and paved the way into the Great Depression after the stock market crash of 1929 [57], inflationary expectations following Roosevelt’s assumption of office led the way out of Depression in 1933 [22]. In this paper, we argue that these lessons from the Great Depression could serve to motivate a consumption campaign, based on a collectivistic and long-term oriented mindset and generational responsibility, to help overcome the current crisis.

3. Research Question, Hypothesis, and the Method Used

The goal of this paper is to find a marked-based solution—which means a sustainable solution that does not rely on governmental intervention—that would allow us to resolve the economic, environmental, and social problems of the contemporary world presented in the introductory chapter. These are the rising environmental constraint, rising inequality, decreasing income and growing uncertainty, and the insufficient support for individuals by both formal institutions and communities. In other words, we are in search of a market-based solution that would allow for the improvement of the economic, environmental, and social context: output growth and the exit from the acute crisis, preservation of the natural environment, the end to income stagnation of the Western middle classes, and the strengthening of community ties.

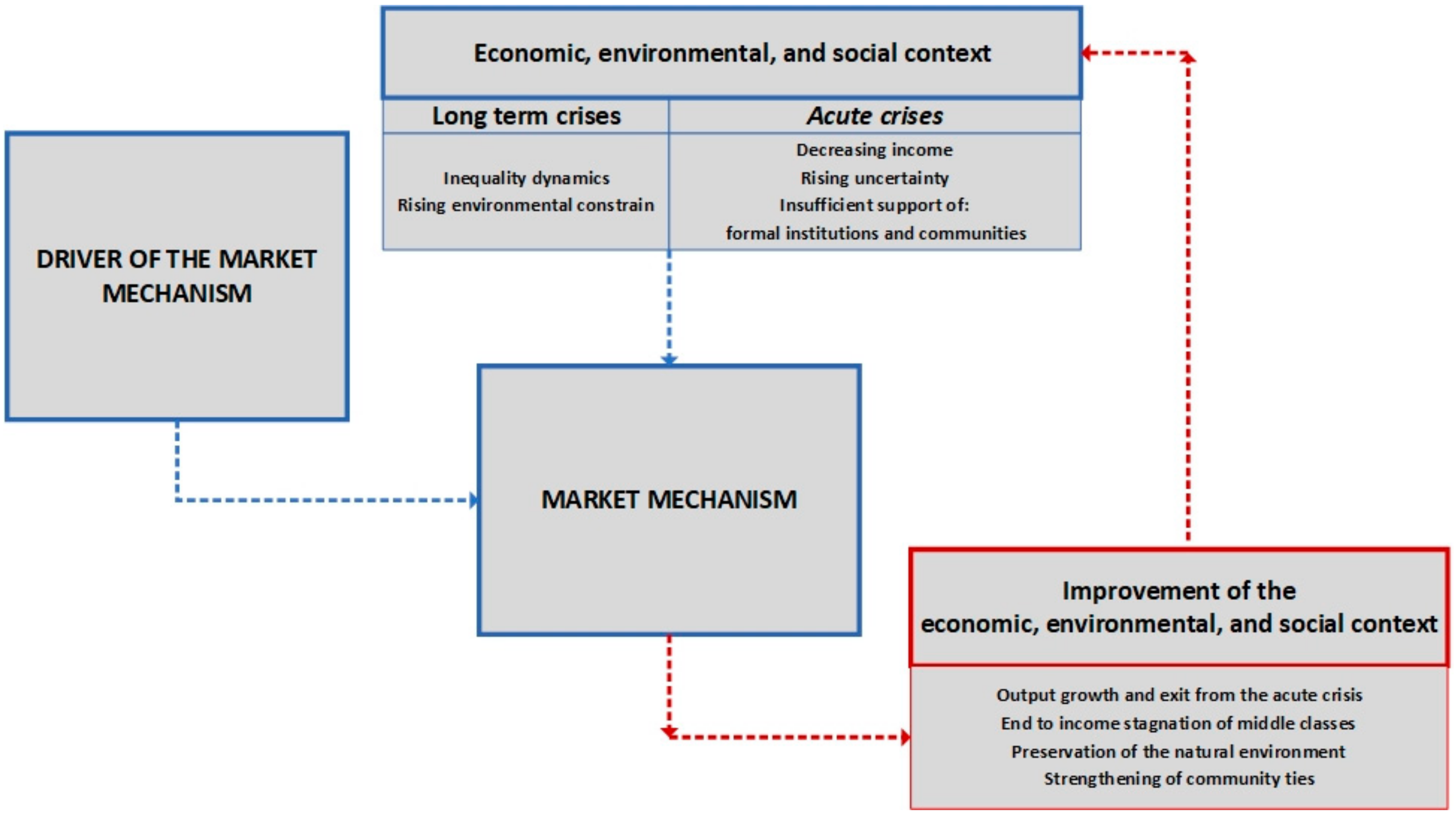

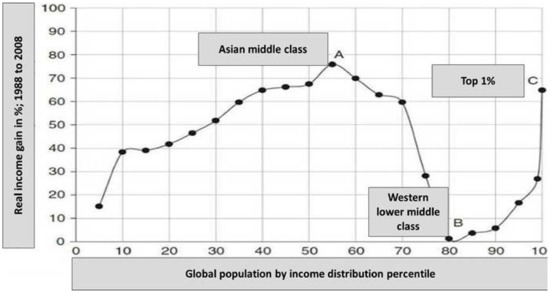

To answer such a research question, we take a holistic, multidisciplinary approach. In particular, we attempt to construct a solution that would be built on the workings of a market mechanism—one that would rely on insights from the economic, management, and marketing theory and practice. Moreover, a mechanism which would be driven by human aspirations to resolve the current crisis for the benefit of the current and future generations of the community to which one belongs, aspirations that derive their strength from a certain system of values. Such a theoretical framework is graphically presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework for a market-based mechanism that would respond to crises.

Our hypothesis is that generational responsibility in consumption, a concept which we introduce in this paper, could serve as the driver of one market mechanism that could effectively lead to the improvement of the contemporary economic, environmental, and social context. We argue that this is because the values that stand behind a generationally responsible approach to consumption very closely match the actions which are necessary to address the problems of the contemporary economy, environment, and society. In the main body of our paper, we thus have the following tasks: to define generational responsibility in consumption and to construct a market mechanism which it can drive so as to achieve an effective response to the contemporary challenges.

The multidisciplinary method which we follow to construct our market-based solution is composed of the following steps. We first use insights from economic history to understand the potential for communities to affect the course of economic crises. We then define generational responsibility in consumption, inspired by a set of values that regard highly on one’s belonging to a community, and describe how it relates to cultural characteristics of different communities established in the management literature. Finally, we use insights from contemporary theory and practice of economics, management, and marketing to both construct a market mechanism that can be driven by generational responsibility in consumption and to argue how it could effectively address the contemporary challenges.

4. Major Past Crises of Industrial Economies and the Role of Communities in Their Development

Major economic crises affect both individuals and communities. What interests us in particular is to what extent communities can influence the onset, development, as well as exit from economic crises. To examine this question, we shall consider a selection of five major past crises of the most developed economies in the twentieth and the twenty first century. These were not the only five crises in that period, and they were not chosen for analysis according to the extent of GDP decline per se. Instead, they are chosen as exemplary to allows us to better understand the influence of the actions of communities on the course of crises. In chronological order, we shall consider three acute crises—the Great Depression, the post-WWII recovery, and the 2008 crisis—as well as two phenomena which we choose to call chronic crises—the crisis of growing inequality and the environmental crisis. We shall focus on their aspects most relevant for our topic. Finally, using the insights derived from these five crises, we shall consider the current crisis that accompanies the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even if we do not analyze any role of communities and their culture in the creation and the burst of the 1929 bubble in the New York stock exchange, the event which preceded the Great Depression, the role of communities in the entry, the deepening, and the exit from this major crisis was very important. The direct loss of wealth through declining equity prices following the stock market crash of 1929 [58] was insufficient to result in the decline in consumption seen in the end of 1929 and in 1930. Instead, the rise in uncertainty about future income which followed the stock market crash led consumers to delay irreversible purchases, those of durable goods [57], until a moment when their income becomes more certain. This decline in consumer demand subsequently led to a decline in production and investment.

A rational decision for individuals, to delay consumption of durables in fear of the future, ex-post turned out to be fatal because it led to a depression which resulted in a loss for most individuals and the whole society. The end of the year 1929 and the year 1930 were thus marked by the described failure to recognize the danger of acting unilaterally and of coordinating a community response instead—by continuing to spend and so helping the economy, the wider community, and oneself in the end. The banking crises of the Great Depression [59] on the other hand resulted from a social unification in an attempt to get one’s money out of banks before one’s neighbors, an equilibrium of selfish fear. International beggar-thy-neighbor policies, reflected in the raising of trade barriers [60], were similar in being motivated by self-interest and in leading to a decline in output of all nations, including those that initiated them. This similarly manifested a lack of solidarity within the community of nations. Trust in governments’ guarantees for the banks reopened after the banking holiday in March 1933 [61], and the adoption of inflationary expectations after Roosevelt took power and the United States went of the gold standard [22], led people to redeposit their hoarded currency and return to spending. It was thus an equilibrium of trust that government’s policies would lead to economic recovery that led the Americans to start acting toward it. It appears that preventing the banking crises of the Depression and initiating the recovery in 1933 would have been hard to achieve, without governmental guarantees, even for a strong community. However, greater solidarity and a sense of a shared destiny within the smaller communities (such as towns served by a single bank) and the whole US society, combined with a realization of what may happen instead if each individual delays consumption, may have prevented the initial economic decline that followed the rise in economic uncertainty.

The common wisdom associates the post WWII recovery of Western Europe with investment using the funds of the Marshall Plan. However, De Long and Eichengreen [21] demonstrate that the funds of the Marshall Plan merely cushioned the losers of transition—the poor of Europe that benefited from regulated prices of food, housing, and heating—when the Western European mixed-economies moved towards less control and more market following the war. However, the social consensus between the various social strata reached after WWII, where both the syndicates and the owners of capital gave up something in the short term in return for longer term gains, allowed for a “bigger pie”, resulting from high growth of a functioning market economy [22,62], which they could later share. This example demonstrates how social agreement—even if it were motivated by the national interest of the United States, which wanted Europe not to slide toward political left, and different economic classes in European societies—led to the period of fastest economic growth in the European history.

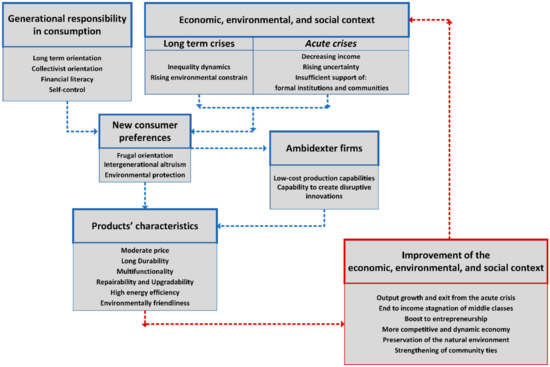

Another development, chronic by duration, should also in our view be characterized as, if not an economic crisis, then a social crisis with economic background. This is the stagnation of real income of Western middle classes in the last thirty years [1,63], a phenomenon which, to a large extent, resulted from elements of globalization: dislocation of production to countries with lower wages and from trade-competition from the same countries [64].

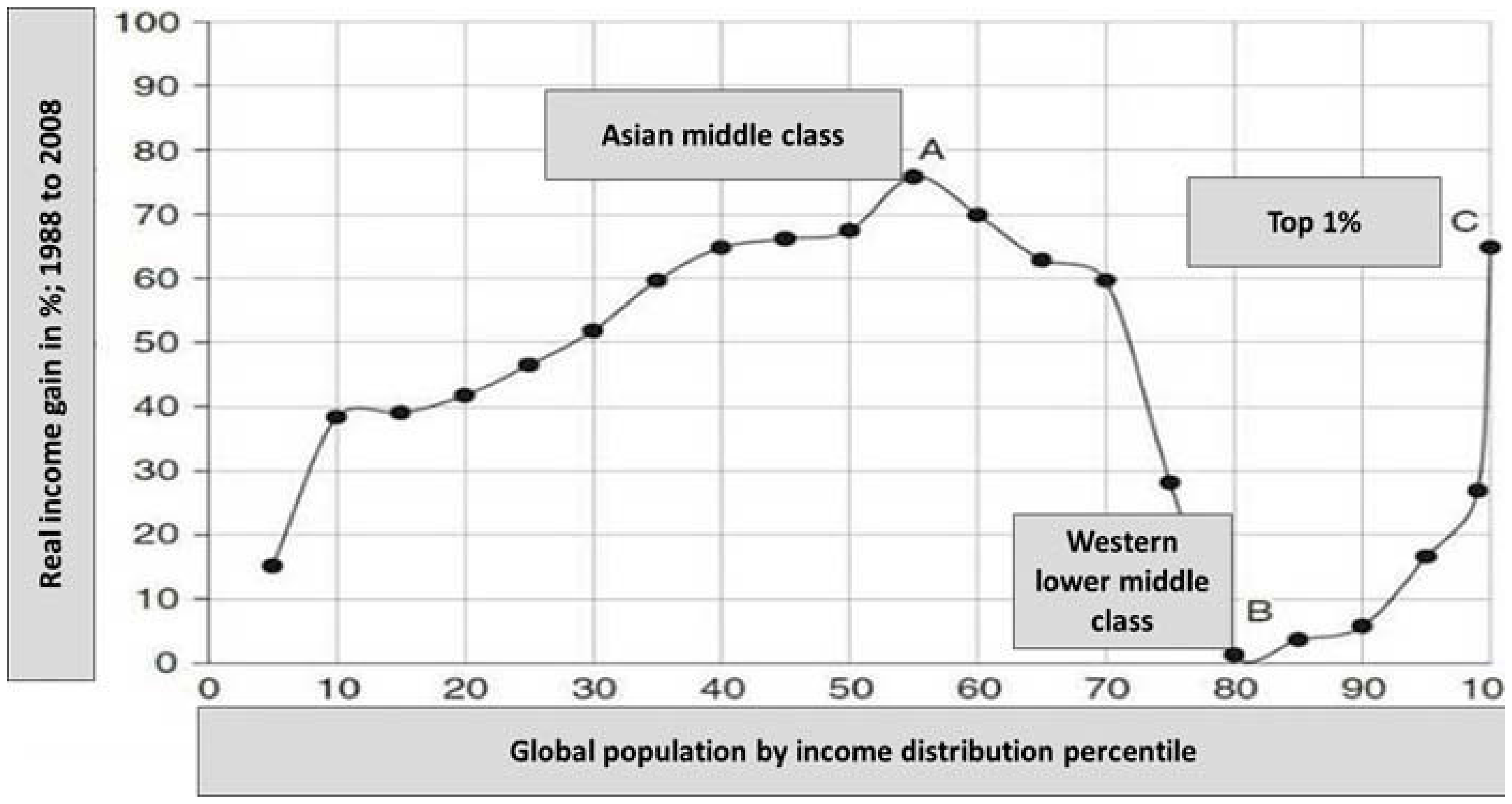

The economic slowdown of Western economies, which started with the Oil Crisis in the 1970s, coincided with the end of the social economic consensus that was achieved after WWII with help of the Marshall Plan. Major changes in the economic system were however initiated somewhat later, firstly in the 1980s in the United States and in Great Britain with the wave of privatizations which accompanied the policies of Reagan and Thatcher, respectively. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the disappearance of ideological competitors to the Western economies, it became politically easier to conduct similar policies in continental Europe, too. Even though the economic mix retained more government ownership and intervention than in the United States, Milanović [1] demonstrated that, in the period from 1988 to 2008, there was hardly any growth of real income of Western middle classes, as evident in Figure 2 (the copyright permission for Figure 2 is available from the Supplementary Materials). When we speak about the role of communities in this process, it appears that the solidarity within Western nations—of the owners of capital with middle and lower classes—was weakened, at the expense of either individualism or merely solidarity with one’s own economic class.

Figure 2.

The change in real income in the world from 1988 to 2008 by percentile of distribution [65].

We further argue that the stagnation of real income of Western middle classes, a social crisis with an economic background, can be related to the past and potential future crises as a causal factor. Income stagnation can be compensated in realizing current consumption through higher debt levels, which in part must have contributed to the 2008 crisis and the ensuing European sovereign debt crisis. Simply, had the income of Western middle and lower economic classes grown faster, there would have been less need for their high debt levels, and the shock to the financial system from many not being able to pay back their loans would have been smaller and would have had smaller effects on the real economy. As government spending was directed to support the banking sector, the 2008 crisis in turn led to the European sovereign debt crisis. The economic recovery between the sovereign debt crisis and the COVID-19 crisis was also potentially weakened because of high income inequality. To the extent that political power is proportional to income, and the rich prefer lower taxes, high sovereign debt levels resulting from the 2008–2013 period made it hard to pursue fiscal expansion financed through taxation. At the same time, expansionary monetary policy pursued ad infinitum further increased the debt burden, laying a fertile ground for a future financial crisis.

Looking forward, we must also observe that rising inequality may lead to a lack of confidence in institutions, their justice and efficiency, which could create social tensions and uncertainty that may lead to a decline in business activities [3,66]. A rise in inequality may also lead to a lack of realization of mankind’s productive potential, where poor talented students may not be able to be as well-educated and in the end create as much as they could have in and for a society which would offer them this opportunity. The negative equilibrium to which this may lead is that societies become focused on the relative rank rather than value creating, removing focus away from the sources of economic gain for all. For instance, it may become important whether you are the best student in the best private school in the city, rather than whether what you have actually learned is at or below your full potential. Overall, an equilibrium characterized by more solidarity between different social strata, or a mere more balanced relationship of relative powers of different social strata, could have perhaps resulted in more prosperous previous decades, both in terms of the overall growth and in terms of wellbeing of large parts of the population.

One more phenomenon, also chronic in duration, should in our view be characterized as, if not an acute economic crisis, then a crisis driven by patterns of economic growth and consumption. This is the crisis of the environment, which cannot be analyzed separately from the economic context [56]. Here again communities may be crucial, because longer term collectivist cultures are more likely to care for sustainable and environmentally responsible consumption. Stagnation of income of middle classes is also a factor which may be contributing to the environmental crisis. In particular, when one cannot achieve higher material welfare through consumption of high-quality goods, one may be tempted to do the same though acquiring a greater diversity of goods of lower quality [67]. For instance, by buying three pairs of low-quality shoes of different color which soon end up in the trash and which may in total cost more and last less than one pair of high-quality durable shoes.

Particularly interesting for our analysis is the recent economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, not merely because it is current but also because of the unique ways in which it interacts with communities and their cultures. There are several reasons for this. The underlying cause of the crisis is an infectious disease: the dynamics of its spread greatly depend on the culture of communities. The issues of self-control and discipline of communities, as well as emotional issues related to the sense of belonging to a family and wider communities, the responsibility towards the infected, the elderly, and vulnerable in general, the bonds to one’s nation and to the whole mankind, were all put to trial during the year behind us. This impacted communities directly with potential to either weaken them or strengthen them. The damaging impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic can be seen both in damaging current production and provision of services, and in creating negative expectations about the economic future. Directly affected are businesses forced to close because of the lockdown, as well as those that are related to high disease transmission risk, the demand for which is affected. By acting in ways that limit disease transmission, both individuals and communities can lower the frequency and intensity of the lockdowns, and therefore lower the economic impact of the pandemic. The other transmission mechanism initiated by the pandemic is the delay of consumption of non-essential goods because of the rise in uncertainty about the future [68], much alike the situation in the United States after the stock market crash of 1929 [57].

Both actions of the government that instill trust about the future, and individual and community initiatives to continue supporting the businesses affected by the pandemic by spending (e.g., ordering food from restaurants if you cannot visit them, spending on goods the demand for which fell, like durable goods, in case your job was not affected by the crisis, and alike initiatives) are ways of expressing solidarity and community building which could in the end help us all bear the crisis easier and exit from it faster. One can however only act in the described way if one has a sense of belonging to a certain community, and realizes that one is likely to at least in part share the destiny of such a community, in this case, at least the national society if not the whole mankind. In Section 4, we further discuss how generational responsibility, as a special type of solidarity within communities, can be used as a tool to overcome crises, including the one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Generational Responsibility and Cultural Characteristics

We define generational responsibility in consumption as one aspect of an individual’s relationship toward his wider community, such as his family, parish, nation, or the whole mankind. To what extent, however, should we expect that generational responsibility in consumption could be widespread within a society? Since societies differ in their culture, and since the relationship of individuals toward any wider community in different societies ought to be related to or make a part of culture of these societies, we can expect that members of some societies would be more prone to generational responsibility in consumption than members of other societies [69]. In addition, because generational responsibility in consumption demonstrates care toward a wider community, it may incite other members of the community to reciprocate [70]. The presence of generational responsibility in consumption may thus be self-perpetuating within a community. Generational responsibility in consumption would therefore be more widespread in societies with more such communities. Moreover, when consumption preferences start to be seen as one of the features of a community, individual’s buying decisions could signal their allegiance to a community [71]. If one cares to be identified as a community member, he may thus feel under pressure to engage in generationally responsible consumption if this is seen as a feature of his community. On the other hand, in societies where community ties play a smaller role—where individuals need not consider community members in their actions and need not care for being seen as part of a community—we can expect that generational responsibility in consumption should be less present.

In order to understand the potential for generational responsibility in consumption to exist or become widespread within a society, it is thus important to examine how the cultural characteristics of different societies, where the role of community ties is just one such characteristic, agree or disagree with the concept of generational responsibility in consumption. A prominent categorization of cultural characteristics used in management studies is that of Hofstede [16,71,72,73,74]. Hofstede categorizes cultures into long-term and short-term oriented, individualist and collectivist, hierarchical and egalitarian, male and female, bureaucratic and entrepreneurial, as well as indulging and restrained [12]. In brief, we argue that generational responsibility is an approach to consumption which characterizes long term oriented and collectivist cultures, but allows for a range within the remaining cultural characteristics identified by Hofstede. Several issues however arise.

Firstly, we perceive that both long term and collectivist cultural metrics as proposed by Hofstede are not sufficiently sensitive to context. Hofstede measures cultural metrics of national societies, including their long-term orientation [75], as within-country averages of views of individuals. This however does not allow for differences in the meaning of the concept of long-term orientation depending on whether national culture is collectivist or individualist. However, if an individual considers not only his personal future benefits but also benefits to the whole of his community, which could live longer than its members, what would represent long term for an individual may represent just medium or short term for a community [76]. Moreover, Hofstede argues that in individualistic societies, people care primarily for themselves and their direct family, while in collectivistic societies, groups take care of individuals in exchange for loyalty [77]. However, acts of heroic self-sacrifice for community could be motivated by concern for the community without asking for anything in return. Such apparently individualistic behavior, actions of isolated individuals, could therefore be mistakenly identified as individualistic although it is in essence collectivistic.

Secondly, we believe that it is not possible to judge about the long-term orientation of members of a certain culture from their actions without considering the risks and the uncertainty in their economic and political environment. In particular, risks that the future brings are reflected in a higher discount rate applied to any future payoffs [78]. This makes the present value of these cash flows lower and results in a rational choice for actions that bring shorter-term payoffs [76]. Higher uncertainty may, on the other hand, lead individuals to delay irreversible decisions with long term consequences and boost current spending on perishables [57,79]. Both phenomena could lead to actions which could be perceived to reflect short-term orientation, even if one’s mindset is indeed oriented toward the future. Consumption decisions may therefore appear as not being generationally responsible, even if long term orientation and the care for future generations dominate one’s motivation. Nonetheless, we argue that, with enough wisdom and foresight, long term-oriented cultures that exist in environments of high risk and high uncertainty could still spend in ways which have the potential to generate future benefits by giving flexibility and creating options to seize the opportunities that would arise in the future [80]. In particular, a combination of insurance-like spending as well as investments in abilities that make one adaptable to changes in the environment, such as investment in education, could be characterized as generationally responsible consumption in such environments.

Thirdly, one should be able to differentiate between different sub-types of generationally responsible consumption decisions depending on how wide the community is considered: a family, a syndicate of workers, a religious community, a nation, or the whole mankind. Moreover, one’s system of values and the expected outcomes of one’s consumption decisions are also important in deciding whether they are motivated by generational responsibility or indeed generationally responsible. For example, one could choose to buy from a retailer that charges low prices but pays low salaries to his workers. This could be because one cares for the economic wellbeing of his direct family only, rather than that of his wider community, does not consider economic equality as important in his system of values, or believes that free market economy would result in greater prosperity of all in the long run.

Having explored the agreement between the concept of generational responsibility in consumption and cultural metrics that relate to long term orientation and collectivism, the remaining question is how it agrees with the other Hofstede’s cultural metrics: hierarchical versus egalitarian, male versus female, bureaucratic versus entrepreneurial, as well as indulging versus restrained. While generational responsibility is a feature of long-term oriented collectivist cultures, it does not set such strict demands on the remaining cultural metrics. Instead, it leaves freedom so that cultures with different preferences, which may stem from different systems of values, could still build their own unique generationally responsible consumption styles that maximize their wellbeing. However, just as Fatić and Mladjan [81] argue that not each system of values is equally efficient in that it may not lead to the same level of wellbeing, generational responsibility may still impose, to a greater or lesser extent in different macroeconomic and political environments, some constraints on the remaining cultural metrics. We now proceed to analyze each of these remaining cultural metrics individually.

When we refer to the extent to which a society is hierarchical or egalitarian—measured by how much people accept hierarchies without justification, or strive to equality and demand justification for any inequalities—we can envision that individuals in societies with different power distance may be perceived as acting, and may indeed act, in generationally responsible ways. It could be so firstly because individuals may care for the wellbeing of a community narrower than the whole society, such as their own economic class. In that case, they would not mind consuming goods produced by firms which cartelized so as to offer low salaries to their employees and leave more profit for the owners who belong to their economic class. Alternatively, it could be so even if individuals care about the whole society and individuals ranked highly in terms of wealth and position still care for lower ranked community members—through donations and scholarships, for instance—because nobility obliges (noblesse oblige). Generational responsibility does however impose some constraints on this cultural metric: high inequality may limit social mobility, preventing an efficient allocation of talents and so limiting the productive potential of the whole economy. However, while wealth inequality may even be fully rejected in generationally responsible societies, although it need not be, societies that do not accept hierarchies of job-related positions, and avoid buying products of companies with hierarchical structure, may be inconsistent with a generationally responsible orientation. This is because not accepting the authority necessary to carry out production processes efficiently would likely lead to long term economic stagnation [82].

In a similar veil, a generationally responsible society could rank differently on the male–female scale, depending on the taste of its members. While masculine societies are more competitive, with focus on achievement, material rewards, and heroism, feminine societies are consensus oriented, and prefer “cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak and quality of life” [76]. Consumption decisions could promote masculinity or femininity either by deciding for products of firms depending on their corporate culture, or by buying goods that support different lifestyles. One could however argue that some elements of both could serve generational responsibility since focus on achievement and heroism, male characteristics, should be useful as ways to create wealth and security with which to care for the vulnerable, female characteristic.

We also believe that societies with different preferences for uncertainty avoidance may still act in generationally responsible, even if different, ways. Nonetheless, some openness to take risks is necessary for success in entrepreneurship which could improve the economic wellbeing of both the entrepreneurs and the whole community in the long run. Collectivism could even encourage such initiatives since both strong social ties and community support for entrepreneurs—both in buying their products and in helping by employing them or lending to them in case of business failure—as well as bureaucratic stability provided by the state can create conditions in which entrepreneurs would feel safer to experiment toward business success.

Regarding the remaining cultural metric of Hofstede, indulgence versus restraint, some range of taste for either could be accepted as generationally responsible. Both individuals and communities may need to economize. However, when this becomes difficult to uphold against human desires, some occasional indulgence may be necessary to release the “pressure of wishes”, including those that relate to consumption. This would again enable restraint, delay of gratification of desires, and thrift that benefits communities through generating savings for investment and creating personalities with more self-control.

6. Analysis and Results: Generational Responsibility in Consumption as an Effective Response to Crises

In this section, we use insights from several disciplines to construct a market mechanism driven by generational responsibility in consumption and to explain how it could address the contemporary challenges. We argue that generationally responsible consumption could boost economic recovery after crises, minimize the negative influence of business activities on the environment, end the income stagnation of large parts of population, and provide financial support for the future generations. Moreover, that it could enhance relationships and mutual support within communities. This, in the current economic environment, would be especially economically beneficial by providing the support of communities to entrepreneurs who could help build a more competitive and dynamic economy. Importantly, we argue that generational responsibility could be promoted both from the demand and the supply side: by the consumers who realize its advantages, and by the existing or new businesses that recognize the generationally responsible market segment as a business opportunity and craft effective competitive strategies to succeed in it.

6.1. Generational Responsibility in Consumption as a Bottom-Up Response to Crises

In brief, we think that generational responsibility in consumption, combined with a realization of the devastating impact on the macroeconomy of delaying consumption in times of uncertainty, could help to coordinate a community driven response to crises by driving the way out of crises through consumption. In times of economic hardship, however, it would be difficult to expect consumers to exclusively focus on the products of the highest quality. Instead, buying products of moderate price and of acceptable quality, but durable and repairable ones, would be beneficial for the individual and the community in several ways. Firstly, the durability would avoid the repeated spending of money and time needed for shopping, necessary when consuming products of lower quality. Secondly, it would provide support for the economy and pave the way to exit from crises caused by a decline in demand through consumption of sufficiently valuable goods that have enough value added and demand sufficient expertise to enable sophisticated businesses to prosper and keep employing also the highly qualified work force. Thirdly, the frugality of the approach would allow for some funds to be saved and some bank loans to be avoided for financing future consumption, lowering the overall debt level of households and lowering the probability of future financial crises. At the same time, the concern for the future generations would also favor the consumption of sustainably produced products which would avoid an environmental crisis. Finally, the narrative of generational responsibility, supported by concrete actions, would boost community ties. This could be expected to have a reverse positive economic effect by providing informal support for entrepreneurs, who would more likely dare to start their own business if they know that their community would support them in case they fail. The community support is very important for vulnerable groups whose main motivation to establish own businesses is related to their weak position in the labor market, which makes them consider entrepreneurship as a necessity rather than an opportunity [83]. If community-supported entrepreneurial initiatives become numerous, such an “entrepreneurial revolution” would lower the need for social support payments, as well as provide conditions to reverse the long period of stagnation of the real income of the middle classes of Western economies.

The intention of consumers to behave generationally responsibly depends on their long-term orientation, collectivistic attitudes, financial knowledge, and degree of self-control. Generationally responsible consumers are buying products that help them to balance: limited financial resources, short term and long-term goals and needs, and the wellbeing of the current and future generations of their own family or the wider community to which they perceive themselves as belonging. Quality, price, and environmental impact are the three main characteristics of generationally responsible products. To meet the needs of future generations, generationally responsible products need to be durable, to provide acceptable functionality, and should be easy to upgrade. Additionally, their design should make it possible for customers to repair or upgrade them themselves if they wish to do so, whenever the complexity of the technology necessary to produce them allows for it. Such products, for instance durable and functional furniture, could be valuable both for consumers and for the future generations. Prices of products directly influence consumers’ savings, which can be used for the establishment of their own business or other types of financial support for future generations. We expect that the consumption of such products would result in several favorable economic and social effects, which would furthermore reinforce each other.

Firstly, generationally responsible consumption should enable consumers to strengthen financial position of themselves and their communities, and widen their future consumption choices. The rising real income of the Asian middle class and stagnation of real incomes of the Western middle class positively affects global demand for value-for-money and good-enough products. These products are characterized by acceptable quality and lower prices. During the crisis demand for this type of products grew, which is a rational response to growing uncertainty about own and future generations’ perspective [84]. Frugal behavior results in satisfaction of consumers’ basic needs currently, enabling the consumers to save financial resources to cope with eventual severe constraints in the future. Buying durable, upgradable, and more efficient products, generationally responsible consumers are trying to achieve their own long-term goals and provide for the future generations. Saved money, due to generationally responsible consumption, decreases the need to borrow from banks to finance consumption, resulting in lower cash outflows to service the debt payments in the future. Current frugal behavior gives consumers more autonomy and flexibility in future consumption, and the ability to strengthen their own and financial position of their family or community. Healthier and more stable household finances would also decrease the extent of general indebtedness in society and the probability of financial crises. Behaving generationally responsible, and buying value-for-money products during crises, even if they can afford expensive premium products, customers in the long run could create value and widen future consumption alternatives.

Secondly, because generationally responsible consumption considers the long-term interests of family members and a wider community—from family to society and mankind—it enhances social ties and creates a sense of belonging to a community. Mutual benefits from consumption enable building of relationships inside the community on the basis of reciprocity and solidarity. Depending on the system of values of the community, strong ties and harmonic relationships built during crises could increase the probability that community members would also support the elderly and vulnerable. Communities, as informal institutions, could support the vulnerable more efficiently than formal institutions, which are large and inflexible, and would not adapt quickly to the new reality created during crises. While we have no doubt that the support of state’s institutions would remain necessary, we believe that stronger community ties would decrease the need for their support, contributing to fiscal stability of post-crisis societies.

Thirdly, the interaction between the positive effects of generationally responsible consumption on the economic wellbeing of individuals and on the strength of social ties should manifest itself in building of a more competitive and dynamic economy. During crises governments apply expansive fiscal and monetary policies to boost demand, preserve economic activity, and spark an economic recovery. In addition, governments bail out strategically important companies and financial institutions. These measures are likely to result in growing public debt and they could lead to higher inflation, negatively affecting consumers’ real income. Moreover, these measures reaffirm the strong influence of the government and large companies on national economies, even when they help overcome crises. On the other hand, generationally responsible consumption promotes more active participation of individuals in the economic recovery, because generationally responsible consumers could save money which could be invested in the establishment of their own businesses. Generationally responsible consumption, instead of leading to an economy dominated by the government and large companies, an economy that could suffer from a lack of competition, encourages an entrepreneurial revolution as a response to the economic stagnation.

Today, such an entrepreneurial revolution would be an economic transformation in which entrepreneurs would be supported by their communities which were rebuilt by the temptations endured during the COVID-19 pandemic. It could ensue as follows. Starting to buy during the crisis itself to help restart the economy, and continuing to buy durable products of acceptable quality, would mean that consumption does not have to be frequently repeated in the future and would provide consumers with additional capital that could be used for investments in risky but profitable projects. Those previously employed in production of low-quality goods could in the medium run find employment in the servicing of higher quality ones, or providing services which replace goods (e.g., within the shared economy, like Uber or Airbnb do). Many of these investments would be expected to fail, but some would succeed and create additional value for the investor and the community. The community could provide support for entrepreneurs if their startups fails. Such informal insurance in the form of support to establish a new venture or find employment in a successful firm would encourage entrepreneurs to invest in innovative projects which could result in superior business performance. On the other hand, business success would increase the commitment of entrepreneurs to their community and enable them to financially support it. Initial business success would encourage other entrepreneurial community members to launch their ventures, while established business networks and relationships would help them develop their own businesses.

6.2. Competitive Strategies in the Generationally Responsible Market Segment during Crises

Not only would generationally responsible consumption enable the creation of new businesses, but both new and existing companies could benefit from serving the generationally responsible market segment. This consumption model, as well as the beneficial economic and social effects that result from it, could also be driven by the companies that recognize it as a business opportunity. We argue that successful competitive strategies in the generationally responsible market segment would require ambidexter firms to engage in disruptive innovations.

The COVID-19 Recession has faced multinational companies with a new business reality: declining demand, rising uncertainty, disruptions of supply chains, and changing customer preferences [47]. Traditional business strategies and sources of competitive advantage appear to no longer be enough to satisfy customers’ demands and be embraced by local communities. We believe that, faced with these constraints, companies may need to restructure their business models aiming to deal with broader business and social issues. We argue that companies that would incorporate sustainability in their competitive strategies and would promote generationally responsible consumption would be more likely to survive this recession and emerge from it with a competitive advantage. With business models built on generationally responsible consumption, companies could help preserve natural resources for the future generations, break the stagnation of purchasing power of Western middle classes and create value for customers in the long run, help resolve economic uncertainty, and create new business opportunities. To achieve this, companies would need to thoroughly analyze and clearly understand business risks caused by the recession, government promotion of sustainable business practices, and consumers’ attitudes toward sustainable products in conditions of growing uncertainty.

Strong economic growth in the last couple of decades, especially in large emerging markets, has contributed to growing pollution and devastation of nature; this made environmental protection one of the most important business and social issues [85]. Governments reacted by introducing stricter environmental regulations and providing a broad range of incentives to boost green demand [86]. While their activities, and those of non-governmental organizations, resulted in positive attitudes toward environmental protection among many consumers, they largely failed to boost demand for green products. Buying convenience, product quality and functionality, and prices are considered as factors that prevent environmentally conscious customers to behave ethically and buy environmentally friendly products [48,87,88,89,90]. Although a small but growing segment of consumers are ready to pay a premium price for green products, they are however not ready to sacrifice their quality, convenience, and functionality. During economic crises, such as the current one, consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for green products decreases [11], even more so that of Western middle classes whose income was stagnating even before the crisis.

While emerging markets are characterized by a large frugal market segment, which helps their companies to better understand consumers’ preferences during crises, multinational companies from developed markets often neglect this segment and may not have the know-how to serve highly price-sensitive consumers. Redesigning products from developed markets by cutting their functionality, performance, and reducing the quality of their material may however not be a profitable way to serve the frugal segment; in emerging markets, this approach rarely succeeded [91]. Instead, the ability to create innovations based on new product architecture and design the product to efficiently meet very specific needs of resource-constrained consumers is a precondition to succeed in serving this segment [92].

However, even the business models used to serve frugal segments are in our view not a proper way to facilitate generationally responsible consumption during crises. This is because the ability to serve low income customers, sufficient to succeed in the frugal segment, is just one requirement companies need to satisfy in order to succeed in the generationally responsible segment during crises. In particular, they additionally need to motivate consumers to overcome the crisis of confidence created by growing economic uncertainty, manage to satisfy environmental regulations even with lower production costs, and satisfy customers’ requirements about the quality, functionality, and durability of goods. To simultaneously fulfill all of these requirements, companies have to become ambidexter. Such companies can efficiently exploit the existing competencies and at the same time flexibly explore new ones, trying to balance cost efficiency and product differentiation [93]. Ambidexterity can be achieved only by significant investments in Research and Development function (R&D)and a careful selection of investment projects.

While ambidexterity can manifest itself in the creation of hybrid products or in engaging in disruptive innovations, we consider that only disruptive innovations have the potential to successfully serve generationally responsible consumers during crises. Hybrid products are interim steps between proven old and emerging unpredictable technological solutions [94]. This approach is for instance frequent in automotive companies where companies design hybrid cars combining electric propulsion systems with internal-combustion engines (ICE). In our view, the innovation inherent in hybrid products does not sufficiently improve product features and reduce production costs to be able to promote generationally responsible consumption. However, disruptive innovations should be able to achieve that. They can radically change industry structure and need to have three main characteristics: radical functionality, discontinuous technical standard, and ownership of an innovation [95]. Radical functionality provides customers with a product with new functions that cater to their previously unsatisfied needs. In the context of generationally responsible products, radical functionality created by disruptive innovations could mean the development of products with more than one function—which are able to replace more than one product—decreasing customers’ cost of using a product, and constructing products whose period of functionality is extended. To develop a product with these characteristics and lower production costs—very important during crises—companies may have to use new materials, introduce new business processes, and organizational models, and perhaps outsource some supply chain activities to countries with a cheaper labor force. Durability with lower production costs could on the other hand be achieved by constructing products that may last less than more expensive ones but that could be easily upgraded or repaired by the customers themselves.

To be considered radical, innovations have to impose a discontinuous technical standard in an industry. To set such a new standard, improved functionality and lower costs are not sufficient, but the standard needs to be embraced by consumers globally. To achieve this, the innovator should be strongly integrated with customers, building a joint commitment and mutual responsibility for the success of the innovation [96]. To impose generational responsibility as a new industry-standard, the companies would therefore have to persuade their customers that the new consumption model would create value for them, their communities, the whole society, and the future generations. A way to achieve this could be the creation of new business ecosystems consisting of companies, as their founders, the governments, NGOs, and representatives of the local communities. Governments could for instance be interested in promoting generationally responsible consumption because the concept of care for the future generations could serve to encourage spending in times of crises in spite of economic uncertainty—in order to avoid economic stagnation for the benefit of current communities and future generations—and so support governmental anti-crisis policies. Integration of representatives of these groups and organizations would help in the establishment of a common agenda, joint resources, projects, better communication, and more value to be shared by all stakeholders [97]. Inclusion of customers into business ecosystems would increase the trust between companies and consumers, enhance their ties, and improve the willingness of both to share information and accept the sacrifice of their immediate benefits to support the community during severe periods. The networking of companies and consumers could thus result in improved functionality of generationally responsible products, lower costs of their development, and their growing acceptance in the global market.

Innovations’ ownership influences the disruptiveness of innovations even if it does not have a physical manifestation. This characteristic explains how innovation affects a company’s organizational structure, corporate culture, employees’ motivations, and external factors. Disruptive innovations “unfreeze” the structure of traditional industries and competition between incumbents and newcomers becomes severe [98]. Flexible, innovative newcomers, frequently with digital competencies, use micro entry strategies and focus their effort on small but growing business segments [99]. For this reason, the newcomers, emerging from the micro-segment and possessing superior innovative generationally responsible products, would succeed in encouraging the customers to embrace these products, and the suppliers to adapt their operations to new product architecture and the new business ecosystems. Such a development would also lead the newcomers’ employees to actively engage with their work resulting in a higher productivity, and the management to strive for new ways to improve functional attributes of the products and cut production costs. In this way, the newcomers, if they manage to explain the advantages of generationally responsible consumption to multiple stakeholders, could gradually expand their foothold in the market at the expense of traditional competitors and extend the market segment for generationally responsible products.

One has to acknowledge that traditional competitors of the companies that would promote generationally responsible consumption are large and currently dominant in their respective industries. They could try to prevent diffusion of the disruptive innovations that strive to set the generationally responsible products as the new industry standard. However, if the newcomers are sufficiently successful, at least some of the traditional competitors would have to engage in gradual adaptation of their business models to the generationally responsible consumption model.

Finally, serving of the generationally responsible market segment could further become an opportunity for startups. They are flexible and thoroughly analyze regulation and changes in customer preferences, trying to exploit any changes as business opportunities. Flexible and innovative startups could introduce new generationally responsible solutions, caring about economic, social, and environmental goals. Emergence of this type of startups would also be very important during crises because startups, even if they may not contribute much to GDP, account for much of new employment [100].

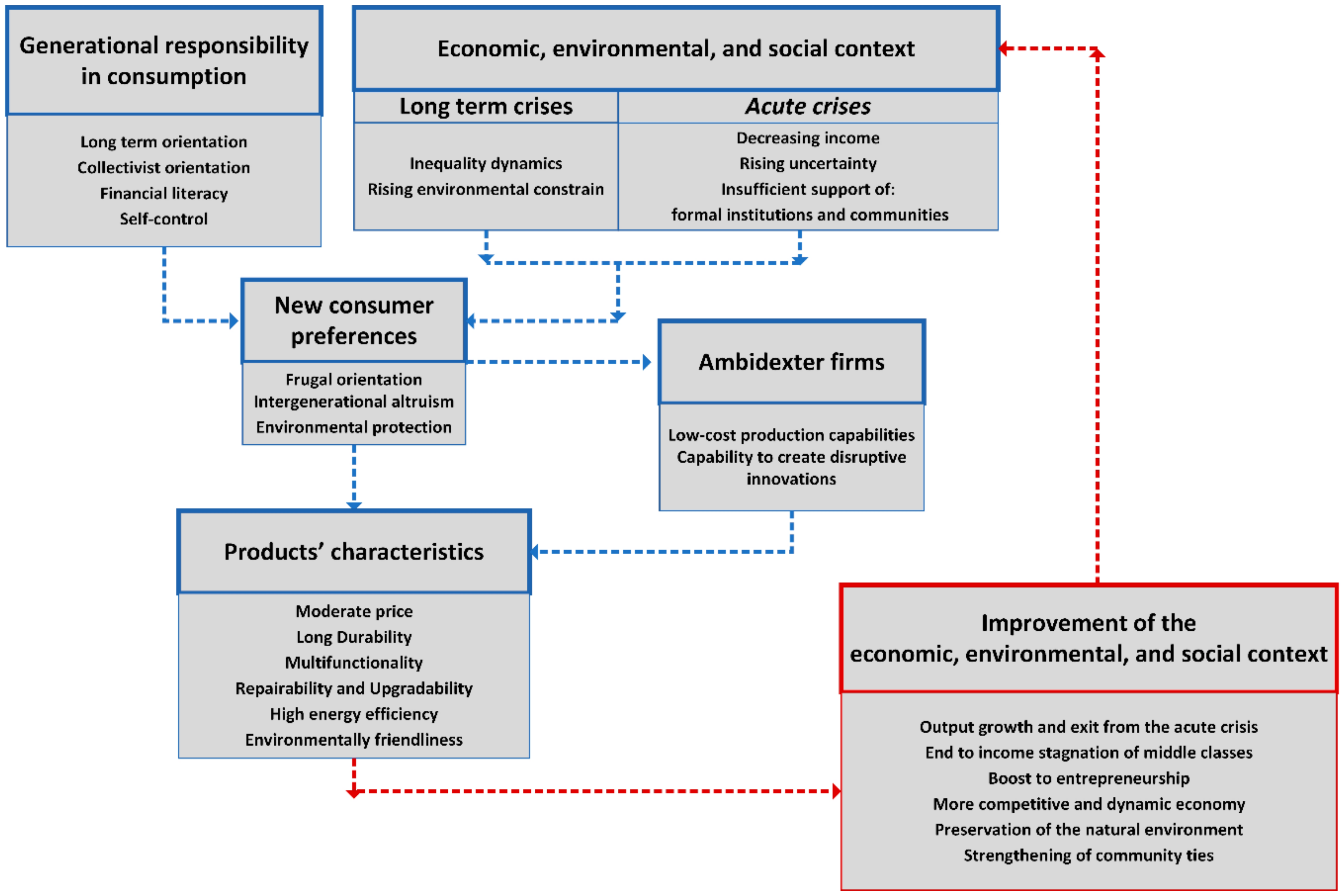

6.3. Generational Responsibility in Consumption as a Driver of a Market Mechanism That Effectively Responds to Crises

Figure 3 below summarizes our analysis presented thus far. It completes the diagram presented in Figure 1, presenting the details of the driver of the market mechanism and the mechanism itself, as we developed in the analysis presented thus far. It shows in which way generational responsibility in consumption can serve as the driver of a market mechanism that can start a virtuous circle of the improvement of the current economic, environmental, and cultural context. Moreover, it presents the internal construction and the workings of this mechanism.

Figure 3.

Features and workings of the generationally responsible consumption model in economic crises.

Two groups of factors, generational responsibility in consumption and consumption context, determine consumers’ preferences during crises. Generational responsibility in consumption depends on: long term and collectivistic orientation, financial literacy, and degree of consumers’ self-control. Contemporary consumption context is characterized by long term and acute crises. Long term crisis, lasting more than three decades, is a result of rising inequality in Western economies, and a growing devastation of natural resources and pollution worldwide. On the other hand, acute crises, such as the current one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, are characterized by: decreasing real income, insufficient support by formal and informal institutions, and rising uncertainty resulting from social, economic, and health risks.

Under these contextual constraints, consumers create a preference toward frugal and environmentally friendly products, and express higher intergenerational altruism. New consumers’ preferences encourage companies to become ambidexter, develop low-cost production capabilities, and create disruptive innovations. Ambidexter firms, both the existing mature ones and those that newly arose, innovate product architecture and are able to develop, design, and launch durable, multifunctional, repairable, and upgradable, energy efficient, green products, with moderate prices. Growing demand for this type of products, a group of value-for-money goods, would help to improve economic, environmental, and social consumption context, resolving acute and long-term crises. The increased demand, motivated by the realization that abstention from consumption could itself produce crises hurting the current and future generations, and companies’ new competitive strategies would boost economic growth and accelerate exit from acute crises. Community ties rebuilt through generationally responsible actions in consumption would create an informal support network and so encourage entrepreneurship, increasing the purchasing power of Western middle classes, and helping the preservation of the natural environment for the future generations. The new improved economic context would lead to generationally responsible consumption preferences that would be willing to pay more for goods of higher quality and prices.

7. Discussion

The main contribution of our paper is therefore the introduction of a novel consumption concept—generational responsibility in consumption—with potential to drive a virtuous circle of transformations in the economy and the society. Generationally responsible consumers balance their own short- and long-term interests, future generations’ interests, and community’s interests, simultaneously creating new business opportunities for ambidexter, agile, and flexible companies. In addition, generationally responsible consumption should contribute to the achievement of the triple bottom line goals, boost economic recovery from the current crisis, and improve the economic standing of the Western middle classes.