The Effects of Mobility Expectation on Community Attachment: A Multilevel Model Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Defining Community Attachment

2.2. Theories on Community Attachment

2.3. Mobility Expectation and Community Attachment

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data and Units of Analysis

3.2. Variables

3.3. Model Specification

4. Empirical Results

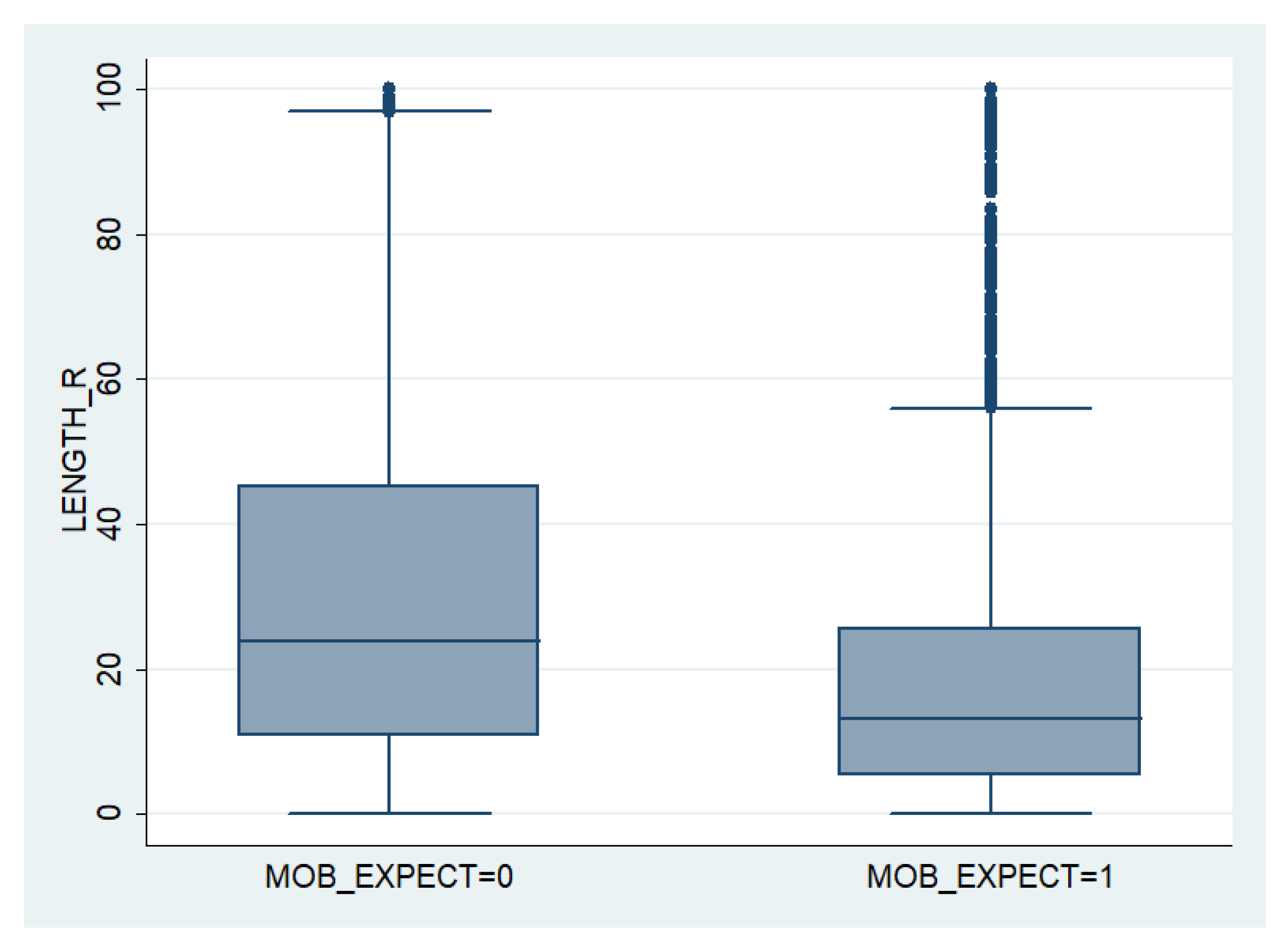

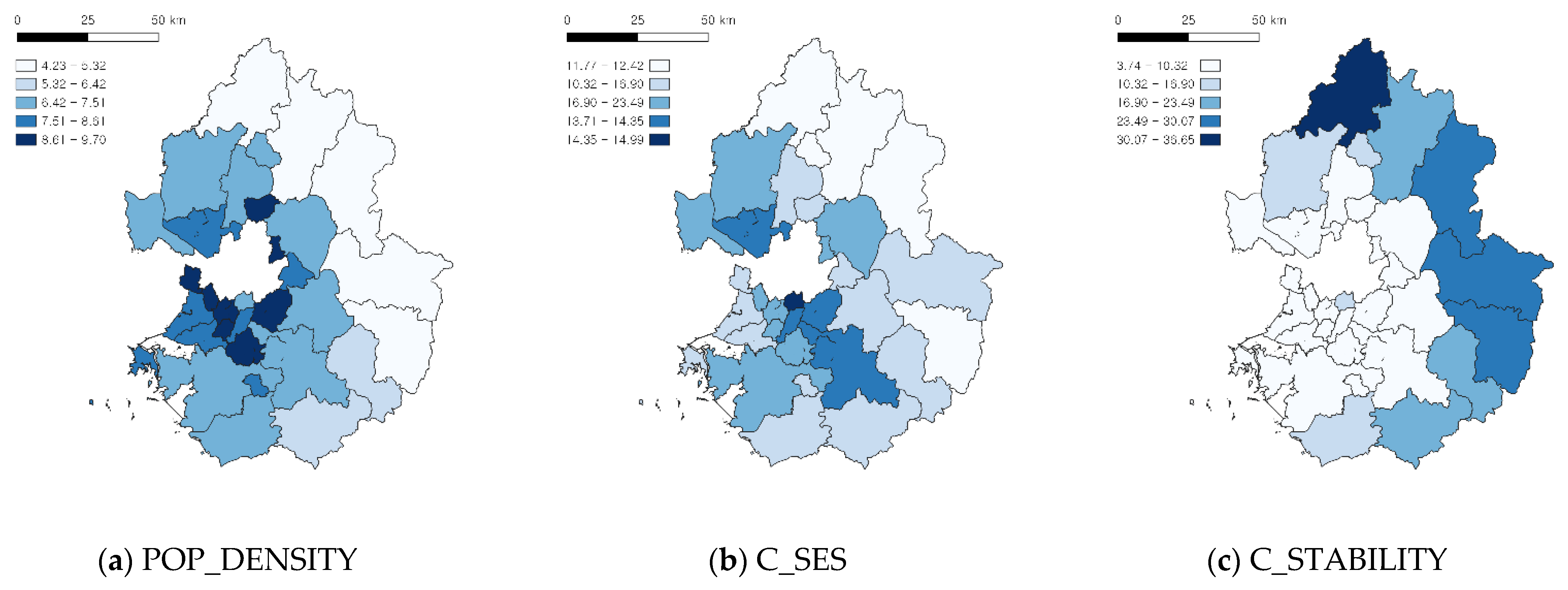

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Multilevel Model Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, S.; Park, D.-H. Community attachment formation and its influence on sustainable participation in a digitalized community: Focusing on content and social capital of an online community. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoff, H. Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Matsuoka, R.H.; Huand, Y.-J. How do community planning features affect the place relationship of residents? An investigation of place attachment, social interaction, and community participation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D.D.; Brown, G. Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, D.M.; Wandersman, A. Sense of community in the urban environment: A catalyst for participation and community development. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1990, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummon, D.M. Community attachment. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place attachment. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Frug, G.E. City Making: Building Communities without Building Walls; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J. Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: A multilevel systemic model. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1988, 53, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnes, M.; Lee, T.; Bonaiuto, M. Psychological Theories for Environmental Issues; Ashgate: Burlington, VT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 Years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Park, J. Effects of commercial activities by type on social bonding and place attachment in neighborhoods. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumaker, S.A.; Taylor, R.B. Toward a clarification of people-place relationships: A model of attachment to place. Environ. Psychol. Dir. Perspect. 1983, 2, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.B. Neighborhood responses to disorder and local attachments: The systemic model of attachment, social disorganization, and neighborhood use value. Sociol. Forum 1996, 11, 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Lee, J.H.; Luloff, A.E. Incorporating physical environment-related factors in an assessment of community attachment: Understanding urban park contributions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ding, J.; Zhu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, Q.; Ji, X. The impact of green open space on community attachment: A case study of three communities in Beijing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentelman, C.K. Place attachment and community attachment: A primer grounded in the lived experience of a community sociologist. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backlund, E.A.; Williams, D.R. A quantitative synthesis of place attachment research: Investigating past experience and place attachment. In Proceedings of the 2003 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium; Murdy, J., Ed.; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 320–325. [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty, J.; Brown, R.B. A multilevel systemic model of community attachment: Assessing the relative importance of the community and individual levels. Am. J. Sociol. 2010, 116, 503–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudy, W.J. Further consideration of indicators of community attachment. Soc. Indic. Res. 1982, 11, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarda, J.D.; Janowitz, M. Community attachment in mass society. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1974, 39, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, J.J.; Hurlbert, J.S.; Haines, V.A. Community attachment in a rural setting: A refinement and empirical test of the systemic model. Rural Sociol. 1996, 61, 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a way of life. Am. J. Sociol. 1938, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodori, G.L. Exploring the association between length of residence and community attachment: A research note. South. Rural Sociol. 2004, 20, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Theodori, G.L.; Luloff, A.E. Urbanization and community attachment in rural areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 399–420. [Google Scholar]

- Aaronson, D. A note on the benefits of homeownership. J. Urban Econ. 2000, 47, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, T.C.; Kingston, P.W. Homeownership and social attachment. Sociol. Perspect. 1984, 27, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, B.J. Are homeowners better citizens? Homeownership and community participation in the United States. Soc. Forces 2013, 91, 929–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J. Getting There: From Mobility to Accessibility in Transportation Planning. Resources for the Future, RFF Policy Commentary Series. 2011. Available online: https://www.resources.org/common-resources/getting-there-from-mobility-to-accessibility-in-transportation-planning/ (accessed on 20 June 2011).

- Bieliński, T.; Ważna, A. Electric scooter sharing and bike sharing user behaviour and characteristics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K.; Kubik, A.; Chen, F.; Wang, H.; Łazarz, B. A holistic approach to electric shared mobility systems development: Modelling and optimization aspects. Energies 2020, 13, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S. The psychology of residential mobility: Implications for the self, social relationships, and well-being. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, J.R. Residential mobility. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1978, 2, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, R.; Van Ham, M.; Feijten, P. A longitudinal analysis of moving desires, expectations and actual moving behaviour. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 2742–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speare, A. Residential satisfaction as an intervening variable in residential mobility. Demography 1974, 11, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speare, A.; Goldstein, S.; Frey, W.H. Residential Mobility Migration, and Metropolitan Change; Ballinger: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kasl, S.V.; Harburg, E. Perceptions of the neighborhood and the desire to move out. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1972, 38, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeeley, S.; Stutzenberger, A. Victimization, risk perception, and the desire to move. Vict. Offenders 2013, 8, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.H. Why Families Move: A Study in the Social Psychology of Urban Residential Mobility; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Sell, R.R.; De Jong, G.F. Deciding whether to move: Mobility, wishful thinking and adjustment. Sociol. Soc. Res. 1983, 67, 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, G.F. Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Popul. Stud. 2001, 54, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, L. How long are exposures to poor neighborhoods? The long-term dynamics of entry and exit from poor neighborhoods. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2003, 22, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manturuk, K.R. Urban homeownership and mental health: Mediating effect of perceived sense of control. City Commun. 2012, 11, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.J.L.; Kasarda, J.D. Contemporary Urban Ecology; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S.; Miao, F.F.; Koo, M.; Kisling, J.; Ratliff, K.A. Residential mobility breeds familiarity-seeking. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Strengthening local government’s right for urban plans: Focused on urban management plan. J. Local Gov. Stud. 2004, 16, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. A study on the autonomy of planning in local government. J. Local Gov. Stud. 2017, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A.S.; Raudenbush, S.W. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grilli, L.; Rampichini, C. Multilevel models for ordinal data. In Modern Analysis of Customer Surveys: With Applications Using R; Kennett, R.S., Salini, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bocarejo, S.J.P.; Oviedo, H.D.R. Transport accessibility and social inequities: A tool for identification of mobility needs and evaluation of transport investments. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R.A.; Kogl, A.M. Neighborhood attachment, social capital building, and political participation: A case study of low-and moderate-income residents of Waterloo, Iowa. J. Urban Aff. 2007, 29, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, V.; Giraldez, F.; Tiznado-Aitken, I.; Muñoz, J.C. How uneven is the urban mobility playing field? Inequalities among hsocioeconomic groups in Santiago De Chile. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlbeck, D. Latino police officers: Patterns of ethnic self-identity and Latino community attachment. Police Q. 2008, 11, 468–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Authenticity, satisfaction, and place attachment: A conceptual framework for cultural tourism in African island economies. Dev. S. Afr. 2015, 32, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Mean | Min | Max | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_BELONG | 31,159 | 2.784 | 1.000 | 4.000 | 0.727 |

| S_HOME | 31,159 | 0.729 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.444 |

| MOB_EXPECT | 31,159 | 0.125 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.331 |

| MOB_DESIRE | 31,159 | 0.134 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.340 |

| MALE | 31,159 | 0.765 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.424 |

| AGE | 31,159 | 53.784 | 15.000 | 98.000 | 14.821 |

| MARRIED | 31,159 | 0.692 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.462 |

| HOMETOWN | 31,159 | 0.139 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.346 |

| EDUCATION | 31,159 | 12.215 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 4.048 |

| INCOME | 31,159 | 5.098 | 2.813 | 6.908 | 0.904 |

| EMPLOYED | 31,159 | 0.736 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.441 |

| LENGTH_R | 31,159 | 30.956 | 0.000 | 100.000 | 27.756 |

| HOMEOWNERSHIP | 31,159 | 0.588 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.492 |

| POP_DENSITY | 31 | 7.346 | 4.229 | 9.700 | 1.506 |

| C_SES | 31 | 13.011 | 11.774 | 14.993 | 0.718 |

| C_STABILITY | 31 | 17.437 | 7.570 | 43.693 | 9.143 |

| MOB_EXPECT | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (=1) | No (=0) | |||

| MOB_DESIRE | Yes (=1) | 2123 (51.02) | 2038 (48.98) | 4161 |

| No (=0) | 1870 (6.93) | 25,128 (93.07) | 26,998 | |

| Total | 3993 | 27,166 | 31,159 | |

| Std. Dev. | Variance Component | Chi-Square | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_BELONG | 0.319 | 0.102 | 761.894 | 0.000 |

| S_HOME | 0.347 | 0.121 | 593.432 | 0.000 |

| Coefficient | Std. Err. | Odds Ratio | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level-1 variables | ||||

| MOB_EXPECT | −0.327 | 0.050 | 0.721 | 0.000 |

| MOB_DESIRE | −0.693 | 0.037 | 0.500 | 0.000 |

| MALE | −0.159 | 0.032 | 0.853 | 0.000 |

| AGE | 0.022 | 0.001 | 1.021 | 0.000 |

| MARRIED | 0.227 | 0.031 | 1.255 | 0.000 |

| HOMETOWN | −0.001 | 0.033 | 0.999 | 0.977 |

| EDUCATION | 0.025 | 0.004 | 1.026 | 0.000 |

| INCOME | 0.117 | 0.017 | 1.125 | 0.000 |

| EMPLOYED | 0.091 | 0.032 | 1.095 | 0.006 |

| LENGTH_R | 0.020 | 0.000 | 1.021 | 0.000 |

| HOMEOWNERSHIP | 0.219 | 0.025 | 1.245 | 0.000 |

| MOB_EXP*LENGTH_R | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.999 | 0.463 |

| Level-2 variables | ||||

| POP_DENSITY | −0.004 | −0.051 | 0.996 | 0.936 |

| C_SES | 0.240 | 0.088 | 1.271 | 0.012 |

| C_STABILITY | 0.008 | 0.009 | 1.008 | 0.383 |

| Additional information | Std. dev. | Var. comp. | Chi-square | p-value |

| Level-2 random effect () | 0.065 | 0.256 | 443.468 | 0.000 |

| Coefficient | Std. Err. | Odds Ratio | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level-1 variables | ||||

| MOB_EXPECT | −0.356 | 0.060 | 0.701 | 0.000 |

| MOB_DESIRE | −0.879 | 0.041 | 0.415 | 0.000 |

| MALE | −0.117 | 0.041 | 0.890 | 0.005 |

| AGE | 0.023 | 0.001 | 1.024 | 0.000 |

| MARRIED | 0.084 | 0.040 | 1.088 | 0.034 |

| HOMETOWN | −0.003 | 0.043 | 0.997 | 0.938 |

| EDUCATION | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.990 | 0.044 |

| INCOME | 0.054 | 0.022 | 1.056 | 0.016 |

| EMPLOYED | 0.044 | 0.076 | 1.079 | 0.091 |

| LENGTH_R | 0.045 | 0.001 | 1.046 | 0.000 |

| HOMEOWNERSHIP | 0.127 | 0.032 | 1.136 | 0.000 |

| MOB_EXP*LENGTH_R | −0.010 | 0.002 | 0.990 | 0.000 |

| Level-2 variables | ||||

| POP_DENSITY | 0.065 | 0.046 | 1.067 | 0.172 |

| C_SES | 0.275 | 0.080 | 1.316 | 0.002 |

| C_STABILITY | 0.023 | 0.008 | 1.024 | 0.008 |

| Additional information | Std. dev. | Var. comp. | Chi-square | p-value |

| Level-2 random effect () | 0.223 | 0.050 | 198.015 | 0.000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, T.; Lim, U. The Effects of Mobility Expectation on Community Attachment: A Multilevel Model Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063441

Song T, Lim U. The Effects of Mobility Expectation on Community Attachment: A Multilevel Model Approach. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063441

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Taesoo, and Up Lim. 2021. "The Effects of Mobility Expectation on Community Attachment: A Multilevel Model Approach" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063441

APA StyleSong, T., & Lim, U. (2021). The Effects of Mobility Expectation on Community Attachment: A Multilevel Model Approach. Sustainability, 13(6), 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063441