Abstract

This paper explores the post-pandemic strategic reorientation of a master in leadership and change management, investigating the conditions for its success and the side effects. The Master, which is part of the Defense Education Enhancement Plan recently approved by the Italian Ministry of Defense, led in partnership by the Center for High Defense Studies and the University of Salerno, aims at developing strategic leadership and change management competencies. The virtualization of the project work sessions that was caused by the pandemic emergency produced unexpected consequences that led the master directors to refocus the program as regards its format and method. The case-study, based on direct observation, unstructured interviews, and analysis of written documents and recorded audio, corroborates the literature regarding the emerging innovative, learner-centered approaches in management education, showing the effectiveness of an integrated educational approach based on traditional in-presence lectures, as well as experiential and project-based learning. It shows how the adjustments devised to cope with the consequences of teamwork virtualization proved to be synergistic, delivering positive outcomes in terms of participants’ satisfaction, learning, and impact. Future research avenues and practical implications are also highlighted, with a focus on the internal and external conditions for successful project-based learning in a distance learning environment.

1. Introduction

In the “crazy” contemporary environment that is characterized by dynamic complexity and unpredictable equivocality, traditional approaches to the education of managers have often proved not just less useful, but positively counter-productive [1] (p. 410).

This is because the mainstream MBA-type educational approach is aimed at transferring explicit knowledge and developing analytical thinking, by reducing the complexity of real problems to a set of theoretical propositions, transferring it to students and testing whether they have learned it or are able to apply it. Such an educational approach that is based on a process of normalization vis-à-vis generalized models is no longer sufficient to prepare students and executives to cope with the challenges of a changing global economy, which indeed require innovative pedagogies.

The University of Salerno, in partnership with the Centre for High Defense Studies, has recently developed an integrated educational approach that connects MBA-type sessions based on in-presence lectures with more innovative sessions based on experiential and project-based learning, giving light to a new Master Program in “Leadership, Change Management and Digital Innovation (LCMDI)”. In the middle of the program, the unplanned virtualization of the teamwork sessions, which was caused by the pandemic emergency, produced unexpected consequences that led the directors to re-focus the project-based learning module. In the light of this interesting evolution, the managerial training program has become the subject of an explorative case-study, which examines the strategic re-orientation of the program, and investigates the conditions for its effectiveness and side effects. In particular, it aims at addressing two research questions, concerning how effective an integrated educational program is that combines taught-in-class lectures with experiential and project-based learning, and which are the conditions for its success in a distance learning environment.

In the following sections, the case study is reported. First, an in-depth literature review is carried out, illustrating the evolution from the traditional business-school models to more innovative learner-centered models of management education. Secondly, the methodology and sources of data are thoroughly illustrated, to prove the reliability and analytical validity of the research. The case study is subsequently described, starting from the analysis of the institutional, cultural, and educational context, and continuing with the reconstruction of the program’s evolution. This allows for highlighting the problems emerged and the solutions implemented in the form of a narrative, as the experience unfolded over the months. Subsequently, the results are discussed and, finally, the limitations of the case study are illustrated, as well as the implications and lessons learned, which led to the introduction of the innovations in the subsequent edition of the master program.

2. Literature Review

The mainstream approach to management education is based on the MBA model that was designed more than fifty years ago, in the industrial age context. It emphasizes the specialistic managerial disciplines that correspond to specific management functions as theorized by Fayol in the first decades of the twentieth century: logistics, information systems, human resources, sales, marketing, accounting, and finance. The approach is mostly deductive and quantitative, with little attention being paid to the interdependencies between each discipline. The employees are merely regarded as human resources, who must achieve the short-term objective of maximizing the shareholder value more than satisfying the interests of a broader set of stakeholders. The instructors are selected and valued for their academic standing and research outcomes that are related to their specific discipline. They are required to discharge their specialistic knowledge and evaluate students’ performance by means of tests and exams.

At the end of the twentieth century, a number of scholars started to question the ability of business schools to effectively contribute to the well-being of economy and of the broader society [2,3,4,5,6,7]. According to Mintzberg [8], a forward-looking critic of Harvard-type business schools, the more these business schools succeeded, the more businesses are destined to failure. Management courses appeared too theoretical and not preparing students well for the very core of managerial roles, mainly consisting of people management and leadership responsibilities [9].

In more recent years, the increasing relevance of the concept of sustainability required a shift in the focus, from the purely financial goal of short-term profit for the shareholders, to the wider goals for a wider set of stakeholders, as summarized by the triple economic-social-environmental bottom line, and fully legitimated by the United Nations Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME) [10]. Sustainable development is an evolving concept based on a number of principles, such as:

- -

- recognizing that economic, environmental, social and religious values compete for importance as diverse people interact;

- -

- taking into consideration differing views before taking a decision;

- -

- adopting a system thinking approach, namely an approach to problem-solving, in which problems are viewed as mutually influencing parts of an overall system, rather than isolated parts;

- -

- calling for great transparency and accountability in governments’ decision making and emphasizing the role of citizens’ participation;

- -

- adopting a precautionary principle, namely avoiding the possibility of serious environmental and social harm when scientific knowledge is inconclusive; and,

- -

- being aware that technology and science alone cannot solve all problems.

This new perspective paved the way for the emergence of a new educational paradigm, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), which is far more than teaching knowledge principles that are related to sustainability: it is education for social transformation, a broad concept that can bring a distinctive orientation to management education. Its features are consistent with the perspectives of sustainable development, as highlighted by the UNESCO sourcebook: Education for sustainable development in action [11]:

- -

- interdisciplinary and holistic: learning content is embedded in the whole curriculum, not articulated in separate subjects;

- -

- value-driven: it is critical that the assumed norms—the shared values and principles—are made explicit so that they can be examined, debated, tested, and applied;

- -

- based on critical thinking and problem-solving: this leads to confidence in addressing the identified dilemmas and challenges;

- -

- focused on the “soft skills”: this allows to innovate in people management and leadership practices; and,

- -

- multi-method: teaching that is limited simply to transferring knowledge is replaced by an approach in which teachers and learners work together to acquire knowledge and play a role in shaping the environment, by means of different methodologies, such as word, art, drama, debate, and experience.

Indeed, there were significant obstacles to the modernization of management education—the relentless marketing policies of MBA schools, the academic nature and profile of the instructors, as well as the ranking and international accreditation system—which reinforced the discipline-based, instrumental, profit-oriented approach of business schools [9].

For these reasons, despite the new emergent needs and the increasing dissatisfaction with the traditional educational methods, the Harvard-type model remained the mainstream approach. Rather than innovating the educational approach, most of the innovators focused on technological innovations, namely the implementation of massive e-learning and the use of new technologies in the classrooms, such as big data analyses, serious games, and business simulations [12]. While the effective use of technology in classroom is appreciable, particularly from a democratization and sustainability perspective, there is the need for “transforming students in active knowledge seekers and experiential learners driven by motivation and values”, which requires, from them, a high level of engagement and a lot more effort [13]. Therefore, innovative pedagogies are required, which can be defined ‘reflexive’ and ‘critical’, focused on developing tacit knowledge or intuition.

As Bratianu [14] observes, “the process of knowledge transfer should be considered in its complexity of interaction of all three fundamental fields of knowledge, i.e., rational, emotional and spiritual knowledge”. Rational knowledge is explicitly expressed by people and incorporated in all types of documents, from legislation to working procedures; emotional knowledge is the result of our bodily reaction to the environment, the outcome of experiential learning; and, spiritual knowledge includes opinions, beliefs, values, and norms, which are incorporated into organizational culture and organizational behavior.

The traditional educational model of business schools is based on rational knowledge, because it is explicit, and it can be easily shared, stored, retrieved, and processed in organizations [14], while the other forms of knowledge are implicit, or tacit, as defined by Nonaka and Takeuchi [15].

The typical management education entails a hierarchical relationship between teacher and learner that privileges the teacher’s explicit knowledge over the learner’s tacit knowledge. However, in contemporary organizations, within the context of a volatile, unpredictable, complex web of economic, socio-political, and technological relationships, and mostly in knowledge-oriented organizations who place considerable emphasis on creativity [16], explicit knowledge is less precious than implicit, for a couple of good reasons. First, unlike tacit knowledge, explicit knowledge can be easily supported by Artificial Intelligence. Secondly, most problems are generated by inadequate problem-setting skills (that have to do with intuition and emotional knowledge), rather than by scarce problem-solving skills. For example, the recent financial collapses are imputable to a failure to recognize the loose coupling between analytical models (Black–Scholes) and the actual financial environment, more than to scarce knowledge of the analytical models [17].

This evolution promotes new educational approaches, in which the learner is at the center of the educational process: examples are inquiry-based-learning or “dialogical mediated enquiry”, a complex inquiry process that dialogically generates multiple perspectives [18] (p. 733); communities of practice as “sites of situated learning” [19] (p. 506), where “a dialogue between problems and whole situations is proposed” [20] (p. 598); a critical, reflexive, philosophically informed case-method that adopts a stakeholder perspective and draws on theoretical tools from beyond the mainstream of the business schools curricula [21]; problem-based learning (PBL) or project-based learning, which incorporate real-time problems or projects in managerial practice [22]; action learning, where students are immersed in real-life experiences or in micro-cosmos “which imitate as far as possible the real world and the real pressures” [23] (p. 493); and, critical action learning, where students focus on the underlying emotions and power relations that “both promote and prevent” their “attempts to learn and improve things” [24] (p. 86).

These studies mainly refer to face-to-face experiences, while there is little evidence of their virtual variety and, consequently, a lack of understanding of how to go about it, namely how to stimulate problem-solving, critical thinking, and reflective thinking in a distance-learning environment.

The competencies of such innovative approaches, which are fully legitimated by the United Nations Principles of Responsible Management Education (PRME) [10], do not necessarily entail abandoning the traditional approach that foster analytical skills. Recent debates around innovative pedagogies reaffirm the importance of non-extreme viewpoints and of integrative learning methods that position experiential learning alongside classroom-taught lessons in context-sensitive learning cycles [25] (p. 189), thus conjugating the practical wisdom of phronesis with the universal knowledge of traditional learning-by-representation in the context of classroom teaching [26] (p. 413). This is also consistent with the ESD principles, suggesting the use of a variety of pedagogical techniques, as stated in the UNESCO sourcebook, Education for sustainable development in action [11].

Integrative learning approaches are not widespread in Italy. To fill this gap, the University of Salerno, in partnership with the Centre for High Defense Studies (Centro Alti Studi per la Difesa—CASD), has recently developed an integrated educational approach that connects classroom-taught lessons with experiential learning and project work, giving light to a new Master Program in “Leadership, Change Management and Digital Innovation (LCMDI)”.

The case study is reported in the following sections.

3. Materials and Methods

The Master Course LCMDI is a part of the new Defense Education Enhancement Plan that was recently approved by the Italian Ministry of Defense and led by the Center for High Defense Studies in Rome, and it is designed and managed together with the University of Salerno. The aim is to provide leadership skills for small groups, large organizations, and the strategic level, with a particular focus on managing change in the digital dimension. The program is based on leading-edge teaching methodologies that were developed by the Armed Forces and by the University of Salerno. It also involves innovative sectors of the Italian institutions, universities, and civil society.

The program is focused on cross-cutting topics that are related to both public and private organizations and explores strategic issues and the broad spectrum of the digital dimension, including cybersecurity. The methodological approach includes innovative educational techniques, experiential and integrated training modules in different locations (defense structures as well as institutions and academic venues), intensive group work, and projects oriented to solve issues proposed by the same organizations to which the attendees belong, through change management techniques.

The participation to the master is open to senior officers of the Armed Forces and Law Enforcement personnel, managers and leaders of public administrations, public utilities, and private companies.

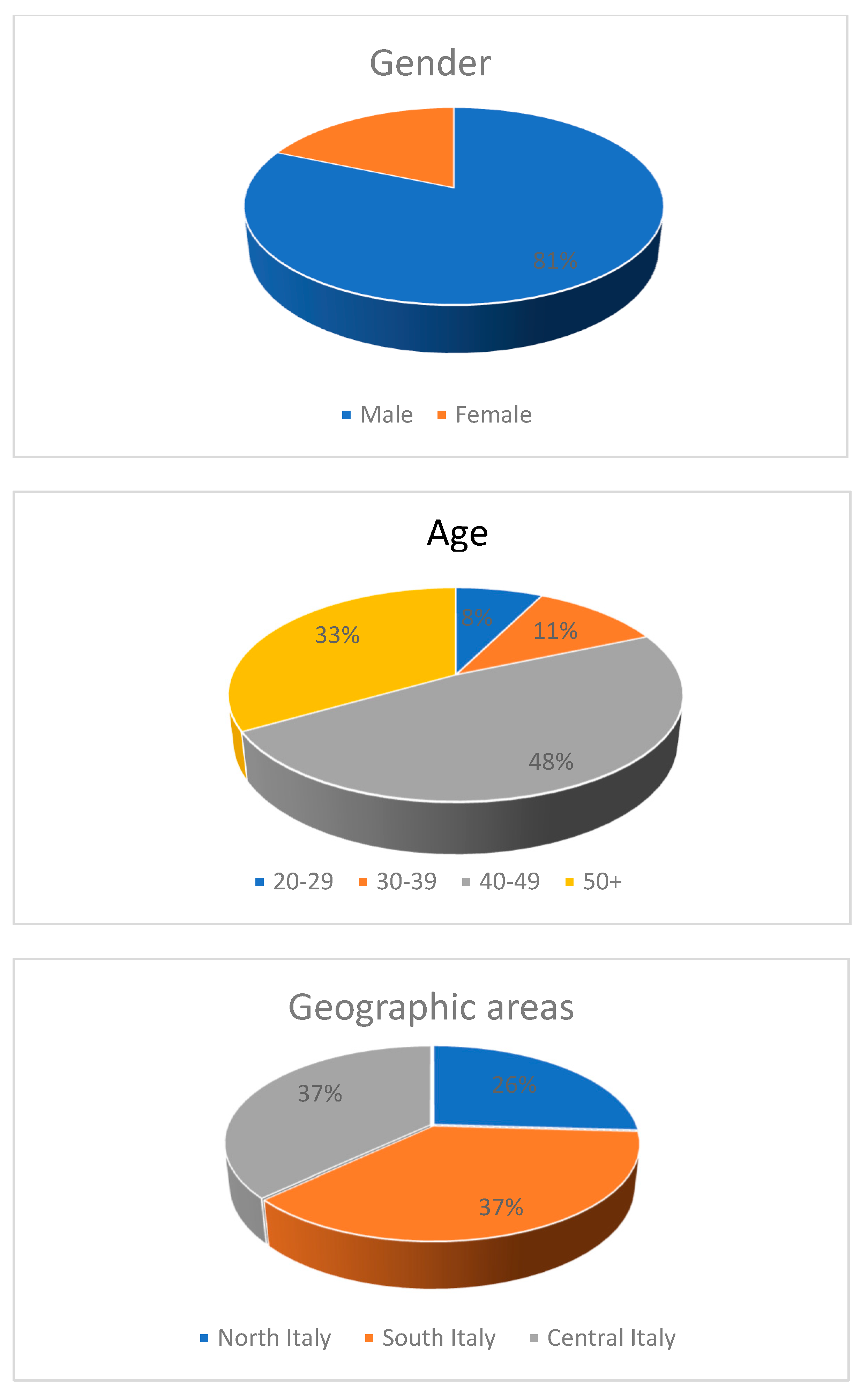

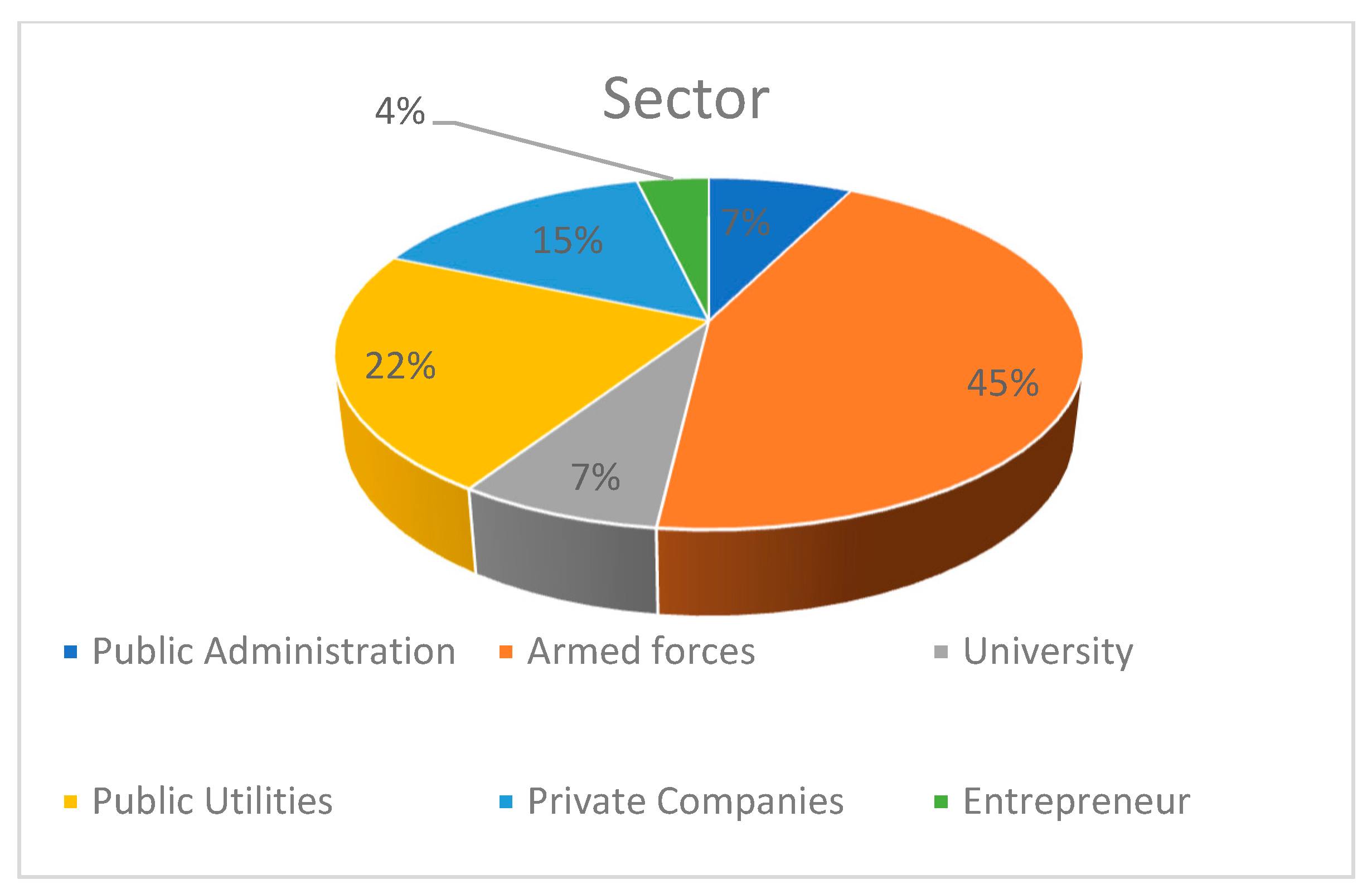

Figure 1 synthesizes the characteristics of the 27 participants.

Figure 1.

Class composition by gender, age, geographic area and sector. Author’s elaboration.

The program is divided into two phases: the first, called “Fundamentals”, articulated in experiential sessions and in-presence lectures, and the second, simply called “Project work”, closely related to the reality of the organizations to which the participants belong. Upon the selection interview, the participants are required to specify which issue or challenge they would like to face. The learners focus and deepen the issue in the “Fundamentals” phase and then elaborate the responses in groups of peers in the “Project work” phase, with the guidance of a team of professors, officers, and skilled “supervisors”. The objective is to produce, at the same time, high quality education and organizational outcomes, in a mutually reinforcing cycle.

The first phase of the Master has been scheduled from October 2019 to January 2020, with a week per month in presence, including three intensive residential modules, which are alternated by distance learning sessions.

The second phase—the project work phase—has been scheduled from February to September 2020, with four intensive residential modules of three full days each. The COVID-19 pandemic has heavily impacted on the planned activities of the project work, originating this case study.

This summary of the course’s features serves the purposes of giving a context for the case study. The case study is, in fact, “an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary ‘phenomenon’ (the case) in depth and within its real world context” [27] (p. 16), and it is specifically recommended by the three main exponents of case study research [27,28,29] as an effective research method when the boundary between the context and issue is unclear and contains many variables. The recommended use of multiple sources of evidence and methods of data collection is another element that is common to Yin, Merrian, and Stake, which allows for depth and breadth of inquiry. In light of this, we included a variety of sources of evidence:

- (1)

- participants’ observation (the authors drew on their direct experience as program directors),

- (2)

- 35 two-hour semi-structured interviews by internal key informants (these are two research assistants recruited as master participants, as illustrated in Figure 1) (see Appendix A),

- (3)

- 27 questionnaires submitted to master participants (see Appendix A),

- (4)

- written documents (reflection papers elaborated by participants as assignment, documents of the exams’ evaluations, participants’ project works),

- (5)

- reports drafted by academic observers and facilitators, and

- (6)

- recorded audio and video (all of the teaching and teamwork sessions).

Regarding the integration of data, we adopted Stake’s constructivist and interpretivist approach to case study research [30]. We began our analysis with all data sources that are related to a sample of three participants, integrating, for each participant, the correspondent semi-structured interview, reflection paper, exams’ evaluations, project work, and evaluations’ reports drafted by the academic observers and facilitators. While collecting the data, we noted down what was being described (the responses that the interviewed people made), but also our initial interpretation of this. We grouped the data into categories and noted down meaningful patterns; when we inductively arrived at plausible explanations, we organized team meetings to discuss our interpretations, and to explore the possibility of alternative perspectives. We incorporated the emerged evidence into the subsequent interviews (progressively enriching the interview schedule), cycling through the process of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. In seeking understanding, we organized online discussions with participants (the course staff and students) as partners in the discovery and generation of knowledge. We presented the final results in the form of a narrative, thus eschewing the reductionist methods of much social science inquiry, which dissolve the connecting links that hold social phenomena together. We used a selection of the original responses to convey findings, as suggested by Stake [30], and compared the results with the literature in the discussion.

4. Results

4.1. The Educational Approach

The educational philosophy of the program is founded on a broad concept of knowledge [14,15]. The course has been deliberately designed to go beyond programs that are increasingly standardized according to global textbooks, by rethinking the hierarchical teacher-learner relationship and then replacing it with a reciprocal and dialogical space and by fostering tacit and emotional knowledge.

Unlike typical project working, in which there is a unidimensional relationship between the academic supervisor and his/her student, who meet in short-term encounters “as strangers, without knowledge of each other’s research agendas, interests and orientations” [31] (p. 9), the project work method that was developed by the University of Salerno entails an open, multiplex educational space where both academics and participants explore and question the subject matter within the context of the organization/institution. In line with this reframed teacher–learner relationship, the academicians must accept the validity of practice and the experience and meaning that learners give to their experience (namely their emotional, tacit knowledge) as a starting point for the generation of theory.

4.2. The Project Work Method: T.R.E.E.

The project work method that is adopted in the Master LCMDI provides the participants with the opportunity to work on a real change project, as opposed to what could be the traditional ‘as-if’ projects that typically gather dust on the library shelf. It has been developed by the course academic director, and it is named T.R.E.E., which is the acronym for the core processes of the change project: Targeted exploration, Reconfiguration, Evaluation, and Exhibition.

The first process, Targeted exploration, has to do with the scenario analysis, the identification of the issue, and the definition of goals, in terms of actionable problem statement.

The Reconfiguration step involves the reorganization of the processes to deliver the mission and goals. ‘Re-’ means that this effort is complicated by the fact it happens within an existing organization, which has its own background, its routine, and its balance. Organizations can be regarded as flying airplanes that never stop. Reengineering efforts must not only make the most of the contribution of all the available resources for the success of the therapeutic path, but they must also make it happen without the airplane falling down, which is, without impairing the organization’s daily operation, in a perfect balance of routine and innovation.

Subsequently, the value that is created by the organizational change process must be assessed, as clearly as possible. This is the purpose of the Evaluation step, which aims at measuring the (not merely economic) value that is produced by the change project in relation to the organization’s mission. In other words, this is about curbing causal ambiguity and assessing the benefits for all of the stakeholders provided by the implementation of the project.

The circle is closed by the Exhibition step, which is both the start and end. On one hand, it summarizes the progress of the project by showing the value produced to the significant stakeholders; on the other hand, through the overwhelming scope of transparency, it helps to wake up other ‘sleeping’ assets, in order to make the project spread like wildfire.

For the ease of illustration, the four steps have been described in a sequence, but, in practice, they have mixed dynamics (sequential, contextual) in the typical iterative-recursive form of a ‘try and learn’ process.

For each of these processes, the participants are provided with original tools and techniques that were developed by the University of Salerno. More than the tools and techniques, the metaphor of the tree is enlightening in illustrating the project work method. It evokes a trunk with the branches embedded in it, that grow and develop into leaves and fruits. Each branch can be regarded as a person, or a value-producing project. The root is what enables the tree to bear fruit by delving deep into the ground—the cultural substratum—from which it takes its nourishment. The fruits—the results of the project—are the concentration of the energy of the life-giving sap that runs through the tree, the accomplishment, whereby a seed can be planted in the ground to start a new cycle all over again. The fruit and the leaves, by falling down, help to produce the nourishment that is soaked up through the roots. They are given back to the ground underneath the tree, as well as into the surrounding soil.

There is a fractal element in both the tree and the T.R.E.E. method, i.e., the fact that every part contains the whole and, similarly, every process of the Targeted exploration, Reconfiguration, Evaluation, and Exhibition cycle, contains the entire cycle.

The fractal element can also be found in the dynamic development of the project. It starts with a single project, just like a tree that puts out branches, and then branches off into other projects, still applying the T.R.E.E. cycle recursively to each of them.

The T.R.E.E. method should be regarded as a project itself, in which assets and actors (educators and learners) are brought together in the best possible combination to offer the greatest value to all stakeholders. This aspect clearly emerges from the case study: the same T.R.E.E. cycle taught in the course as model of change management is used for changing the educational strategy in light of the new pandemic scenario.

4.3. The Evolution of the Program: A Promising Start

The program started with a full immersion in the experiential learning at the Air Force Academy in Pozzuoli (Naples) and at the Military Police school in Florence. The boats, the kitchens, the wooded hills offered unusual settings to apply leading-edge methodologies of experiential learning, helping participants to explore their strengths and enhance areas of weakness, improve relational and leadership capabilities, and promote a climate of trust.

The four dimensions of the Italian Air Force leadership model—self, team, organizational, and strategic leadership—were applied in the “Fundamentals” phase through a strong team building and self-awareness program, and a deep dive into strategic thinking, seen as the product of critical thinking, creative thinking, and systemic thinking (also through the lens of complexity theories). The value-based, participative, transformational leadership approach that was proposed to the participants was actually testified across all activities.

The program continued with the in-presence lectures at the Centre for High Defense Studies in Rome. Intense daily seminars that upskilled the participants in the fundamentals of leadership and change management, as well as digital transformation, created a common management terminology and shared concepts across the participants, instilled complex causal thinking and critical reflexivity among participants, provided a forum where participants could exchange ideas, and identified synergistic opportunities of networking among them and with key actors of their economic and institutional contexts. The participants were also engaged in teamwork sessions that were focused on the problems that they had illustrated in the admission interview (some of these problems were linked to an organizational intent expressed by the employing organization, others were the fruit of participants’ reflections, in the absence of an organizational commitment). In order to further strengthen the teamwork competencies and enrich the innovation potential, under the impulse of the military co-director, the participants were invited to converge in groups, which could propose broader strategic projects resulting from the overall synergies.

4.4. Pandemic Emergency and Strategic Re-Orientation

The project work phase of the program was going to begin at the end of February, with the in-presence teamwork sessions at the University of Salerno, when the pandemic emergence (an unpredictable ‘black swan’) obliged the University to close all in-presence courses and introduce on-line delivery methods according to national regulations and guidelines. With the in-presence teamwork being no longer possible, the program staff rapidly re-organized the program, so that the project work sessions could be delivered and recorded on the online platform that was selected by the CRUI (the conference of the rectors of Italian universities): Teams.

The first module—Targeted exploration—took place in March with three full days of on-line plenary and teamwork sessions. The module took the steps from the organizational intents that were discussed in Rome, starting by an in-depth investigation of the issue identified with the goal of reframing it in the form of actionable problem statements. Plain discussions took place for hours among participants, leading to interesting analysis and operational solutions that were focused on immediate performative goals, but did not challenge ‘business-as-usual’ assumptions or identify critical aspects, from which new ways of conceptualizing the value creation system of their organizations could emerge. For this reason, the class performance was regarded as a little below the expectations, when considering the high potential of the selected participants.

This under-performance continued over the second module—Reconfiguration—in which the organizational analysis was just surfaced; in particular, participants carried out their stakeholder analysis task, but did not go in depth in the exam of the motivations, financial or emotional interests of the stakeholders, as well as the strategies to win their support or to manage their opposition. In addition, a number of them delivered complaints to the course staff.

Despite this, they all provided a positive feedback during the official sessions. The planned customer satisfaction questionnaire was not administered online, but facilitators and observers were gratified with many thanks and appreciation, by word and by email.

“I think there was no problem with postponing the submission of the anonymous questionnaire to a more suitable time, when we could have the class in presence. I am so sure that participants are satisfied, they continually praise and congratulate us for the program.”Instructor 3

When asked what they appreciated more, the participants praised content expertise for the incremental help to upskill and improve their job tasks, so coming across as unaware that a greater potential contribution could lie in helping them to critically look and reconceptualize some aspects of their organization/business. Being surprised by these responses, and stimulated by the military partner, the academic director decided to revise the strategy with a view to reconfiguring the program in the light of the changed scenario. To this purpose, the same method taught to participants—T.R.E.E.—was adopted, with the four processes of targeted exploration, reconfiguration, evaluation, and exhibition.

4.4.1. Targeted Exploration

The aim of the exploratory phase (Targeted exploration in terms of the T.R.E.E. method) of our project was to investigate participants’ true feelings and expectations. An important help to gain insight came from the two key informants, who submitted semi-structured interviews to both participants and facilitators, adding an internal perspective to understand participants’ views regarding the critical aspects of the transitioning process from pre-pandemic in-class lecturers to post-pandemic on-line teaching.

All of the recorded sessions were listened to twice and the reports drafted by the observers and the facilitators were discussed and compared, for each participant, with the correspondent semi-structured interview, the reflection paper, and the exams’ evaluations.

At the end of the exploration, a plenary staff meeting was organized to highlight the findings, in general and for each participant, as well as to discuss possible adjustments of the program. It emerged that, despite the positive feedback coming from the class, there were some critical issues regarding the distribution and quality of knowledge exchanges.

First, a reduction of participation both in the teamwork sessions and in the cross-group plenary discussion was observed: as compared to the teamwork sessions made in presence during the first part of the program, in the online sessions more density of verbal interactions was recorded, but the exchanges involved a lower number of participants, who tended to prevail more and more in the discussions. Regarding the quality of knowledge exchanges, these were mostly limited to explicit knowledge and, according to the observers, tended to include pre-constituted ideas, unauthentic meanings, and domesticated rules of analysis.

“I was surprised to listen at convenient interpretations and concepts repeated hundreds of times. The discussion did not appear to me genuine, as if there was a sort of inhibition.”Participant 18

It emerged that most participants, belonging to organizations that were used to work within long-term contracts and/or used to adopt lifetime employment policies, displayed what could be called ‘conservative mindsets’, namely a low propension to run risks and innovate. The attempts of some facilitators to unfreeze participants’ inhibition by proposing jokes or confidential revelations in addition to the presentation of tools and techniques for the project work had been unsuccessful: their interventions appeared to be fascinating yet unsettling and discomforting, provoking skillful attempts to avoid the hardest questions. This discomfort is brought into focus by a comment from a facilitator…

“Anytime I tried to create a friendly climate through confidential discourses, the group participants went off on a tangent.”Facilitator 5

…and from a participant:

“I find it difficult to express my feelings in a recorded group session. Outside the session I call my friends for a face-to-face exchange.”Participant 19

In the light of the exploration, the most likely cause of these behaviors appeared to be the fact that the recorded online sessions hindered knowledge transfer, reducing “knowledge entropy” [32] as well as the quality of the interactions, with the loss of tacit and emotional knowledge transfer. In addition, the opportunities of casual interactions diminished drastically, and participants tended to restrict their interactions with those most similar to them.

In the light of these findings, a reconfiguration was carried out as regards the program’s format, content, and method, with an emergent strategy integrating the deliberate one.

4.4.2. Reconfiguration

A number of innovations were introduced in the program, aimed at a redesign of its format, content and method (Reconfiguration, in terms of the T.R.E.E. methodology).

Adjustments in the structure of teamwork sessions were introduced, in order to stimulate intuitive reasoning and facilitate the communication flow.

Informal meetings were organized after the online recorded sessions, as a completion ritual (but outside the formal schedule), allowing for participants to talk about how they felt about the session, what they learnt, and what they valued in each other. It appeared to be a powerful way for facilitators seeking to develop intimacy, openness, and reflexivity in virtual teamwork.

“After initial inhibition, it seems to me that participants opened up and went deeper and faster.”Participant 11

The duration of sessions was reduced, having realized that, during the online sessions, the concentration is less durable when compared to the in-presence session. Participants were asked to show their face, having realized that non-verbal communication was of paramount importance in facilitating the exchange of tacit knowledge.

In addition, the third module on critical evaluation (“Evaluating”) was postponed to the fourth module on communication (“Exhibiting”) and, within this, an Exhibition Day in presence was organized at the Centre for High Defense Studies, where the groups could present their work in-progress not only to the other participants and to the military staff, but also to an authoritative audience of top managers, who could challenge their ideas constructively.

Another innovation was to offer some talks to recall and strengthen the teambuilding experiences of the first modules. Marcello Lippi, the charismatic coach of the Italian national football team winning the world cup in 2006, who warmed-up the whole class, was particularly appreciated: all of the participants took parts to the online session for more than five hours, and actively intervened with questions and comments, abandoning any inhibition and shyness.

Furthermore, a new methodology for the project work sessions was developed by the academic course director, inspired by the SECI model [15], to stimulate the free flow of implicit and explicit knowledge during online groupwork sessions. It is based on five processes, according to the I.B.R.I.D. acronym.

- a. Intuition (internalization)

- b. Brainstorming (socialization)

- c. Reconceptualization (externalization)

- d. Integration (combination)

- e. Deutero-learning

- a. Intuition (facilitator and individual participants in plenary session)

The first phase, which corresponds to the internalization phase of SECI model (explicit to tacit), is led by the facilitators’ leader, who consecutively poses five challenging questions to the participants that are connected in plenary through the Team platform. The questions concern the elements of a value proposition, which represent the reconceptualization of the value creation system of an organization. To give a response, participants are pushed to intuitive processing, drawing on their tacit knowledge. Five rules are imposed to stimulate the spontaneous flow of intuition and prevent conformism, namely the responses need to be:

- -

- immediate (max 30 s), so there is no time for analysis;

- -

- synthetic (max 4–5 words), to facilitate a holistic approach;

- -

- with no explanation, to avoid in this phase any attempt to rationalization;

- -

- eventually multiple, with each response written in a separate click (as on a post-it), in order to facilitate the reconceptualization and design, namely cutting and pasting assets/activities/gains; and,

- -

- sent to the facilitator’s private chat (to avoid reciprocal influences between participants).

- b. Brainstorming (parallel virtual coffee-break conversations led by the group facilitators)

Subsequently, each facilitator puts the responses of the group members in a synoptic table, through appropriate tools (to highlight the different individual responses of each member of the group and facilitate comparisons), and then shares the synoptic table on the screen, asking the group members to identify the best value proposition. Each participant, in turn, is called to illustrate his/her responses to the five questions, thus sketching an embryonic value proposition and, in the attempt to advocate his/her own ideas, is prompted to share his/her tacit knowledge (‘socialization’ mode of the SECI model, namely tacit to tacit). To facilitate the free flowing of communication, a virtual space has been created where group members can freely interact on a social level (for example, virtual coffee or appetizers, virtual winery tour and tasting). The team facilitator has a list of challenging, appreciative questions to promote discussion and brainstorming.

After the process of brainstorming, the team facilitator leads the group to converge towards one or two drafts of shared value proposition, which represent the reconceptualization of the value creation system of an organization according to a process of collective intuition.

- c. Reflection (facilitator and individual participants in plenary session)

This is a process, corresponding to the ‘Externalization’ Mode of the SECI model (tacit to explicit), in which the reconceptualization of the value creation system, as emerged from the brainstorming, is rationalized through a reflection on the value proposition. Each participant re-examines the path that was suggested by the five questions, by addressing further questions posed by the team leader, and producing, through specific tools and templates, an explicit and reasoned illustration of what has emerged from the individual and collective intuition.

- d. Integration (parallel formal group sessions led by group facilitators)

This process, corresponding to the ‘Combination’ mode of the SECI model (explicit to explicit), entails sharing and integrating explicit knowledge regarding the reconceptualized value creation system. It is a collective reflection process, organized through peer consultancy groups or group relations conferences.

- e. Deutero-learning (plenary session and group sessions, facilitators and whole class)

The deutero-learning phase aims at stimulating metacognitive competencies, and it entails a collective reflection concerning the process of learning itself (rather than the value creation system). The facilitators’ leader poses some questions to stimulate the collective discussion, so that reflections concerning the learning itself are elaborated. Each team facilitator, after a group discussion, presents the responses to the questions as fruit of the collective discussion, and then the final take-home messages are collectively distilled.

4.4.3. Evaluation

On the basis of the reports, questionnaires, participants’ reflection papers, and final project works, it was possible to evaluate the effects of the program (and of its reconfiguration) on learners’ satisfaction, their participation, learning, and change management competencies (Evaluation phase of the T.R.E.E. method). The effects were mainly positive, thus corroborating the literature concerning integrative learning methods, as well as the new perspectives on education for sustainable development, and proving the effectiveness of the strategic reorientation that followed the post-pandemic virtualization.

The introduction of informal moments produced an emotional improvement that—we can suppose—also influenced cognitive and practical abilities, on the basis of the integrality of humans and the fact that each variation of one aspect affects all other aspects. Participation increased significantly, and several ‘timid’ participants, who had shown low propension for a critical approach, re-flourished in the new setting.

The interactions, previously mechanical and instrumental, had gradually become increasingly filled with emotions and feelings. Some sub-groups reached a sort of psychological symbiosis. Moreover, the strengthening of social links combined with the inquiring attitudes, free from the immediate instrumental interest, produced a stronger impulse towards change. This was also possible thanks to the excellent experiential learning sessions that were delivered at the beginning of the program by the military partner, which had been reinforced during the project work sessions.

Regarding the IBRID methodology, some participants initially challenged the academics as to why and how the cues brought to bear were relevant to their immediate project task. This challenge forced reflexivity on the part of academics, who replied that the immediate task was less interesting than the understanding of the drivers and dynamics of change, since the final goal was to stimulate fresh thinking to open up possibilities and offer a new framework for viewing the organization or the business. Subsequently, the participants started to appreciate the methodology more and more: the individualized inquiring approach stimulated scenario discussions that could generate multiple-futures thinking. The multiple-futures analyses encouraged critical reflexivity [33], which, while potentially unsettling for participants, provided them with an opportunity of seeing their organization in a critical and innovative way.

“It was a bit hard but I think I got new ways of seeing my organization and my future engagement.”Participant 9

Broader thinking offered space for resisting the overwhelming exploitative tendency and for moving beyond instrumentalism and, at the same time, for reducing the risk of an implicit support of the status quo. Interesting issues and strategic dilemmas emerged and they were explored, mostly in the field of digital transformation, and innovative value propositions were drafted by each participant, enriched with dense post-it notes. Most of the final projects were excellent: participants themselves were surprised at how capable they were to elaborate a change project when the conceptual tools were used in the perspective of action:

“I did not imagine that I could carry out such a project through which I caught a glimpse on my future action”Participant 20

“I could reach unexpected results since I received personal professional, and peer-group coaching perfectly tailored to my specific needs”Participant 2

The final impact was the pursuit of a more innovative agenda, that stimulated fresh thinking, rather than adherence to a narrow pre-defined problem-solving mode, and this constitutes the real value-adding contribution of the master program. For example, a participant who started with the idea of developing a safety app for train passengers, ended up by developing a new co-creative concept of the relationship between the transportation company and its clients, in a society 5.0 framework.

The unexpected opportunity for participants to present their work in-progress during the Exhibition Day organized in the presence at the Centre for High Defense Studies provided them with new impetus to change, so that they enthusiastically undertook the challenge of making sense of their experience and preparing an appreciative presentation of their projects. This preparatory work stimulated the learners to expand the way for thinking about what was unique in their organizations in terms of resource and competencies that could be applied to create new opportunities. In that occasion, anonymous questionnaires were submitted to the learners, which participated in large number, despite the pandemic, and they were scanned and sent to the university for elaboration. The average assessment for each professor, facilitator, and member of the staff was very high, as well as the average assessment for each member of the administration and organization staff. A large number of optional observations were also added, which were mostly useful and gratifying comments.

The innovations introduced had not been consolidated over time or grounded in theory and experience, they just unfolded under the pressure of immediate need, after the ‘pedagogical triage’ and the strategic re-orientation. This caused resistance on the part of some academics, who had already found it difficult to accept an action learning approach replacing their comfortable lecturing methodology, and showed opposition to a further change of approach, which obliged them to study new methods and deal with a higher level of uncertainty on the project output.

Here are examples of academics’ complaints.

“The uncertainty on the outcome of the group dynamics makes me anxious…”Professor 2

“The fact that I cannot schedule in detail the sessions is very stressing…”Professor 8

“I am too fully busy to find time to study new methods and approaches…”Professor 5

Administrative staff also opposed what Crozier [34] would call ‘technocratic resistance’. They raised a number of technical and administrative obstacles to the possibility of adjustments, making the life of the director difficult, who had sometimes to obtain that the norms of master regulation could be waived (the inversion of module three with four, a shift in the assignment deadlines, a change of the didactic syllabus, and so on).

Finally, difficulties came from a couple of companies, who did not support the learner efforts and, in some cases, even denied their employees the possibility to carry out the internship, creating apparently unsurmountable problems (problems that were ultimately solved).

On the whole, the Evaluation was positive and robust (based on evidence from multiple sources), so that, as a result of the experience, it was decided to re-propose the master program for the following year and to permanently incorporate the adjustments that were introduced to the virtualized version of the program.

Regarding the Exhibition phase, this is represented by this paper.

5. Discussion

The case study corroborates the recent advancements in management education literature around innovative pedagogies reaffirming the importance of integrative learning methods [25], as well as the new perspectives on education for sustainable development [11]: the design of the master program integrating different methodologies, as a manifold matrix to be explored, rather than a linear trajectory to be run, appeared to efficaciously offer the diversity that is required of a postmodern curriculum and effectively respond to differing student learning styles. Indeed, only rarely can innovations be realized by wearing just one hat from beginning to end, to use de Bono’s metaphor [35]; often, managers are required to think with the other hats as well.

The pandemic emergence appeared to invalidate the approach adopted, and the case study shows that it was mostly due to the on-line recorded teamwork sessions that had replaced the in-presence work group, thus hindering spontaneous knowledge transfer (an ineludible condition for the effectiveness of brainstorming). The strategic re-orientation that has informed the project-based master program, as a result of a real time response to the unexpected evolution of the context, produced, as illustrated in our analysis, positive outcomes in terms of participants’ satisfaction and learning; in addition, it also significantly increased the impact of the program, thanks to a shift from merely technical solutions to deeply innovative change management approaches. In addition, the participants had the opportunity to hone virtual leadership, which is particularly relevant in contemporary post-pandemic organizations and businesses. The experience shed light on how to go about virtual project-based learning and what are the benefits and the barriers to uptake, thus allowing to fill a gap in knowledge, as highlighted in the literature section.

Regarding the adjustments devised to cope with the virtualization of teamwork, it appears that these did not fully compensate for the lack of physical dynamics, nevertheless they captured several aspects of being present together, particularly when the choice of looking each other on video allowed for verbal and non-verbal cues and feedbacks. From this perspective, the planning of chat time before the start of the formal online sessions proved to be useful, too.

The IBRID methodology that was developed for the online project work sessions proved to be particularly efficacious in increasing knowledge entropy [32] and enhancing innovation. In particular, the sharing and integration of individual responses in the brainstorming and integration phases allowed for timely give-and-take in a communal space, and demonstrated building knowledge together, not just at an individual level; moreover, the planning of virtual appetizers or wine tasting in the brainstorming sessions introduced an element of informality and helped the participants relax and connect on a deeper emotional level.

On the whole, the re-oriented program produced an impressive amount of new knowledge, besides fluidification of communication and enrichment of exchanges, and helped participants to re-conceptualize the value creation systems of their organizations.

The case study also allowed for exploring the external conditions for the success of the educational approach. A critical success factor appeared to be the commitment of companies/administrations that are involved in the program. A couple of participants were unable to deliver the project due to the poor support on the part of their organizations, and/or their multiple and conflicting organizational roles. This proved that an advanced learner-centered methodology cannot magically substitute for a lack of sponsorship or unaddressed organizational politics.

Moreover, a cohesive team of prepared and committed facilitators is required. Resistance encountered on the part of some facilitators to engage in action learning and, mostly, to adjust their methodology, corroborates the findings from literature [9], indicating that this is not an easy task for many management educators, who are used to the orderly and predictable teaching patterns that have dominated universities over time, and are more comfortable discharging their knowledge ex-cathedra within their respective disciplinary domains. They find it hard to redefine their educational strategy, reorienting their methodology from a digital perspective. Along with this, they have to learn how to use the platform, how to prepare video tutorials, how to design distance lectures, and how to carry out virtual tutoring.

The culture is also of paramount importance. The positive results of the educational experience were also based on the introjection of both teachers and learners of critical thinking and strategic perspectives on collective action. From this point of view, the strong investment in the “Fundamentals” phase on team-building and experiential leadership education, up to the strategic level, had paid off with a culture favoring change management. It is not possible to evaluate the global effectiveness of the program in case the “Fundamentals” phase had been delivered on-line: this is an important indication for future research efforts, which could evaluate the effectiveness of online experiential training. For the moment the lesson learned is that, not to be wished as unique pedagogy to follow, distance learning could be considered to be a pedagogy that is valuable enough to be re-proposed in the following classes, supplementary to the sessions in person, and after having tested and refined all of the details.

6. Conclusions

Management education is a leadership and management endeavor. For high educational effectiveness, the same high-quality leadership that is required for running any human system is needed. The evolution of managerial literature, through many different paths to the transformational leadership theories, has seen a parallel, but often inconsistent, development of management education approaches. It is time to close the gap between education and the real world, and this has been attempted with a master aimed at developing strategic leadership and change management competencies that are crucial for coping with the contemporary challenges.

The case study corroborates the literature about the emerging innovative, learner-centered approaches in management education, as well as about education for sustainable development, showing the effectiveness of an integrated educational approach that connects traditional in-presence lectures with experiential and project-based learning. Moreover, the analysis fills a gap in knowledge regarding the virtual variant of this learner-centered philosophy, highlighting its compatibility with both traditional lectures and project-based learning, and showing how the blending of in-presence and distance learning represents a powerful approach to effectively develop successful leaders in the post-pandemic world. In addition, the adjustments devised to cope with the consequences of teamwork virtualization proved to be synergistic, delivering positive outcomes in terms of participants’ satisfaction, learning, and impact, and allowing for deeply innovative change management projects. As a result of the learning path of the two institutions, the master program has been designed for the following year, incorporating the adjustments introduced and taking the enabling factors identified in the case study into consideration. Future research avenues and practical implications are highlighted, with a focus on the internal and external conditions for successful project-based learning in an online environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A. and F.G.; Data curation, F.G.; Formal analysis, P.A.; Investigation, P.A. and F.G.; Methodology, P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Semi-structured interview—facilitators and lecturers

Outline of the interview questions

How the transition to online classes impacted on your capacity to:

- design efficient and effective lessons

- provide diversified learning experience to all the students

- use feedback to improve participants’ learning experiences

- adapt your teaching to the context and the participants’ experiences

- build good personal relationships with participants

- build a climate of trust and inclusion

- stimulate participants’ risk taking and performance

- create learning experiences that develop critical thinking, creativity, intuition

- create learning experiences that transfer explicit and implicit knowledge

- make concepts and skills clear and accessible to all participants

- capture participants’ attention and keep them on task

- keep a smooth flow of communication and reduce delays, distractions, waiting times and downtimes

- identify the teamwork routines to follow and get the most out of these routines

Semi-structured interview—master participants

Outline of the interview questions

- Are the current sessions the first online training sessions you attend?

- For you, what are the benefits of online teaching and groupwork sessions? What are the challenges do you face?

- What about your ability to conciliate study, work and family?

- Do you consider adequate (in quantitative and qualitative terms) the interactions with the facilitators and the academic and military staff?

- Do you consider adequate (in quantitative and qualitative terms) the interactions with your colleagues? And with your team-mates?

- What is your feeling about recording sessions?

- What is your opinion about the accessibility of the platform and other technological aspects of the online sessions?

- Do you think you received enough support from the course staff?

- Tell me about a time when you felt “out of sight, out of mind” when working from home.

- If you could change one thing about online teaching and teamworking, what would it be?

Final evaluation questionnaire—master participants

Questions about the quality of teaching (clarity, teaching material, teaching methods, content, assessments),

Questions about the quality of coaching/facilitation (academic advising, access to academic staff, access to facilitators and military supervisors, quality of feedback, connection between teaching and project works)

Organization (administrative support, administrative procedures, quality assurance procedures)

Facilities (class facilities, transportation, parking, food services, logistic)

References

- Chia, R. Teaching paradigm shifting in management education: University business schools and the entrepreneurial imagination. J. Manag. Stud. 1996, 33, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, W.G.; O’Toole, J. How business schools lost their way. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2005, 83, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. Training Managers, Not MBAs. In Mintzberg on Management: Inside our Strange World of Organizations; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. Managers Not MBAs: A Hard Look at the Soft Practice of Managing and Management Development; Berrett-Khoeler Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolai, A.; Seidl, D. That’s relevant! Towards a taxonomy of practical relevance. Organ. Stud. 2010, 31, 1257–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Fong, C.T. The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2002, 1, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, K.; Tempest, S. The winter of our discontent—The design challenge for business schools. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. Crafting Strategy. In The Strategy Process: Concepts and Contexts; Mintzberg, H., Quinn, B., Eds.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Belet, D. Renewing Management Education with Action Learning. In Educational Leadership; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, E.; Bridgman, T. Why management learning matters. Manag. Learn. 2017, 48, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Sourcebook. Education for Sustainable Development in Action. Learn. Train. Tools 2012, 4. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/926unesco9.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Auger, P.; Mirvis, P.; Woodman, R. Getting lost to find direction: Grounded theorizing and consciousness-raising in management education. Manag. Learn. 2018, 49, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Hadad, S.; Bejinaru, R. Paradigm Shift in Business Education: A Competence-Based Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C. Designing Knowledge Strategies for Universities in Crazy Times. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 8, 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfler, V.; Ackermann, F. Understanding intuition: The case for two forms of intuition. Manag. Learn. 2012, 43, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A. A Behavioral Approach to Strategy—What’s the alternative? SMJ 2011, 32, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoukas, H.; Dooley, K.J. Introduction to the special issue: Towards the ecological style: Embracing complexity in organizational research. Organ. Stud. 2011, 32, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, S.; Preece, D.; Dawson, P. In search of innovative capanbilities of communities of practice: A systematic review and typology for future research. Manag. Learn. 2016, 47, 506–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengis, J.; Nicolioni, D.; Swan, J. Integrating knowledge in the face of epistemic uncertainty: Dialogically drawing distinctions. Manag. Learn. 2018, 49, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, D.; Johannisson, B. Learning as an entrepreneurial process. Rev. Entrep. 2009, 8, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, J.M.; Moyano, A.; Romero, V.; Ruiz, R.; Rodríguez, J. Student long term perception of project-based learning in Civil Engineering Education: An 18-Year Ex-Post Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Rieple, A. Entrepreneurial decision-making in a microcosm. Manag. Learn. 2018, 47, 471–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, R.; Abbey, G.; Langenhan, M.; Bell, D. Finding critical action learning through paradox: The role of action learning in the suppression and stimulation of critical reflection. Manag. Learn. 2018, 49, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.; Simon, J.; Gabrielsson, J. Combining experiential and conceptual learning in accounting education: A review with implications. Manag. Learn. 2017, 48, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statler, M. Developing wisdom in a business school? Critical reflections on pedagogical practice. Manag. Learn. 2014, 45, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, C.A. Linking research and teaching: A study of graduate student engagement. Teach. High. 2000, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C. Exploring knowledge entropy in organizations. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2019, 7, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, S.; Chia, R.; Burt, G. Relevance or ‘relevate’? How university business schools can add value through reflexively learning from strategic partnerships with business. Manag. Learn. 2014, 45, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, M. Le Phénomène Bureaucratique. The Bureaucratic Phenomenon; Tavistock Publications: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- De Bono, E. Sei Cappelli per Pensare; BUR Biblioteca Univ. Rizzoli: Milano, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).