1. Introduction

The Roma population is an ethnic minority of northern Indian origin living in almost 50 countries due to migratory movements [

1]. Roma groups have become the most significant ethnic minority lacking a unified state in the European Union, and The Council of Europe’s (2012) average estimate of the Roma population in its region is close to 11 million [

2]. This number includes 2.8 million Roma in Turkey and 1.2 million in the former Soviet Union. A further 1 million Roma live in the Western Balkans, and the remaining 6 million live within European Union territory. Roma people are particularly numerous in Central and Eastern Europe and the western part of the former Soviet Union. Moreover, Süli-Zakar (2012) [

3] reports that the number of European Roma has doubled and almost tripled in the four decades since the International Romany Union. They now have more than 7% ethnicity in Bulgaria, Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Hungary. Many European population studies, therefore, indicate their specific demographic status. Unfortunately, current information is not concrete and accurate enough for this, and further research is, therefore, essential. Herein, Slovakia is a suitable study area because of its significant percentage of Roma ethnic population.

The growing number of Roma in several European regions, including Slovakia, has promptly increased research in an endeavor to understand this ethnic group’s demographic behavior. Haviarová (2004) [

4] further contends that it is essential for this ethnic minority to have accurate demographic knowledge to plan and take successful measures.

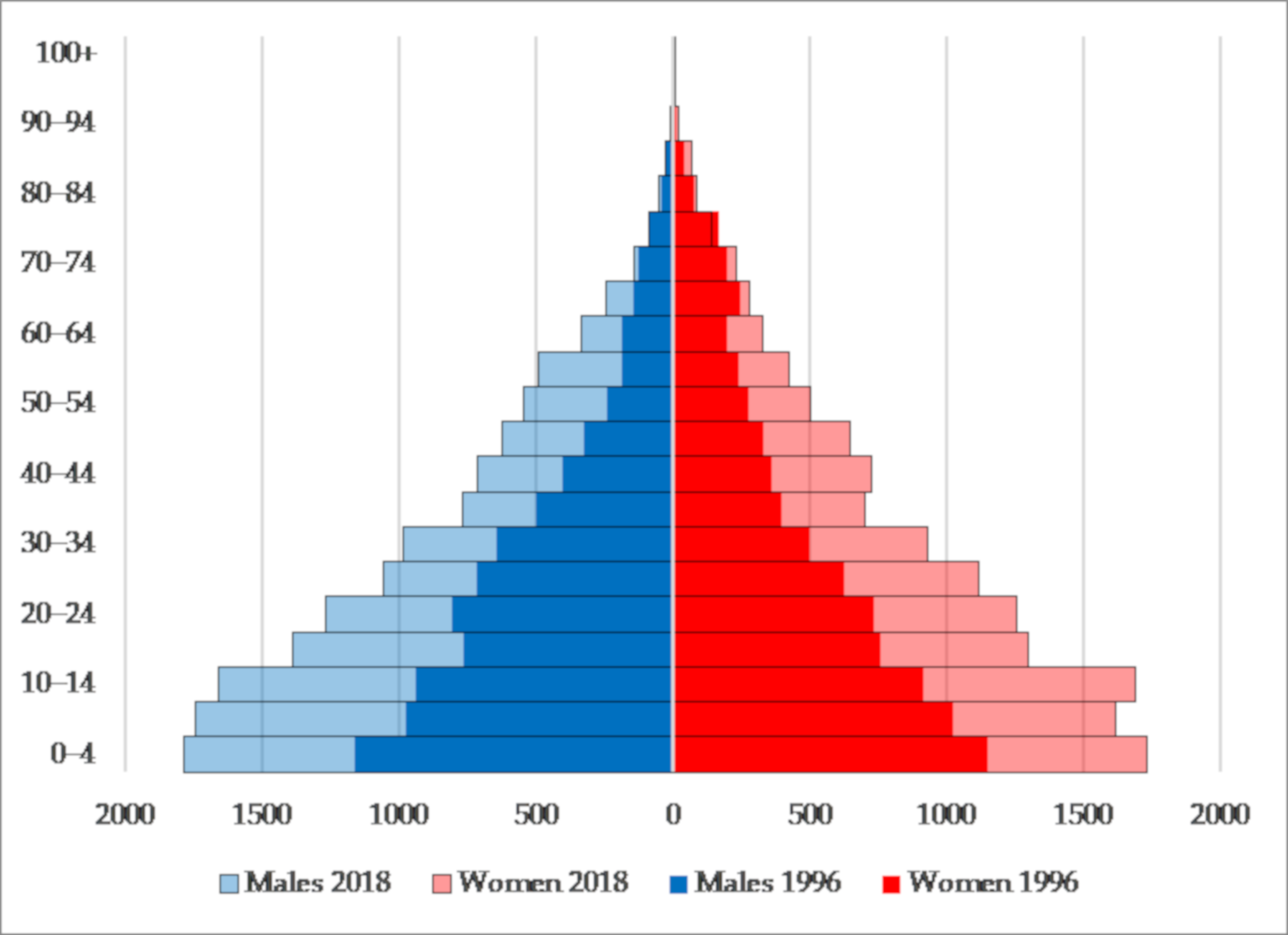

Demographic indicators also highlight that the Roma community in Slovakia is represented by a youthful population with a progressive age structure where reproductive norms significantly differ from the Slovak people. The Roma household survey conducted by the European Union Fundamental Rights Agency, United Nations Development Program, and the World Bank indicate that the Roma population has higher birth rates and a smaller proportion of older people in the population [

5]. The high number of Roma children reflects the traditional family model and a low level of education. The result is a demographic profile that contrasts strongly with the narrowing general population pyramid. Central and South-Eastern European countries are now facing rapid ageing of the majority population [

6], which unfortunately creates a significant challenge for the productive integration of the growing Roma population in mainstream society.

Current research into the Roma population is beset with problems. The significant difficulty is the lack of reliable statistical data on the structure and demographic processes in the Roma community. For example, Knežević (2013) [

7] and Šprocha (2014) [

8] consider that statistical monitoring of demographic and socio-economic changes in the Roma population based on data census and vital statistics are challenging because Roma tend to hide their ethnic identity, and this conceals the true demographic situation. Süli-Zakar (2012) [

3] further explains that the European Roma population constitutes one ethnic group but does not constitute a homogeneous community. Therefore, the various groups have different integration levels, which must be considered in all unifying strategies. Similar observations are made in Slovakia, where demographic changes in the Roma population are closely associated with their level of social integration. The most noticeable demographic deviations have appeared in segregated Roma settlements with the minor integration level [

9]. This lifestyle is often comparable to less developed countries.

One of the most significant challenges in demography and population geography is to determine the demographic behavior of ethnic minorities accurately. This especially applies to the Slovak Roma population, and our study, therefore, examines the trends in their demographic processes from the end of the 1990s. This required close monitoring and evaluation of trends that converged and diverged from those of the Slovak population. While monitoring this entire ethnic population group, the review was primarily concentrated on Slovak municipalities with a high Roma concentration and low degree of integration. We ensured that the sample covered the characteristics of the entire target group as closely as possible, and we were able to establish essential data on Roma living in extreme conditions. The surveyed Roma population lags significantly behind the majority of Slovakia in the demographic transition. As Šprocha and Tišliar (2016) [

10] point out in connection with the Roma population, it should be noted that this is probably the last relatively large population group in the European environment for several centuries, in which the process of demographic transition has not yet been completed. On the other hand, Šprocha and Bleha (2018) [

11] claim that it is debatable whether we can even talk about the beginning of the demographic transition in the case of the Roma in Slovakia. Both populations are divergent in demographic behavior due to different levels of cultural and economic development. The research results may provide some insight into the movement of demographic transition that the Roma do not seem to have yet overcome.

2. A Brief Overview of the Roma Population in Slovakia

The number of Roma in Slovakia has increased tenfold in the last 120 years, while Slovakia’s population has only doubled (

Table 1), and the very first estimates of the number of Roma in Slovakia were compiled from an inventory in the reign of Maria Theresa and Joseph II at the end of the 18th century. While

Table 1 depicts the recording of this census at approximately 20,000 [

12], it was impossible to determine the exact number, e.g., Džambazovič (2001) [

13] used the 1893 Hungarian census to record 36,000 Roma in the territory. While more accurate numbers were expected from the 1927–1947 inventories, Jurová (1993) [

14] considered those numbers underestimated. Moreover, the registration of nomadic Roma happened to be difficult, and Slovak/Hungarian borders were going through changes from world war redistributions. Despite these before-mentioned anomalies, there is a 35% increase registered in the number of Slovak Roma from 1927 to 1947, while Slovakia recorded only a 3% population increase.

State policy after World War II was oriented to Roma assimilation. While policies included mandatory schooling, access to residential housing, and steady employment [

6], Slovakia did not formally recognize the existence of Roma nationality from 1945 to 1990. More reliable data came from those in 1970 and 1980, but this information was evaluated separately [

16].

National authorities recorded 160,000 (3.5%) in Slovakia in 1970, and only 10 years later, in 1980, 200,000 Roma (4.1%) were identified. At that time, the Slovak census commissioner endeavored to determine the total Romany population from local records of Roma inhabitants, with emphasis on both who was identified as Romany and who identified as such, and then on the determination of Roma lifestyle, native language, and anthropological features.

The last more reliable records of Roma in Slovakia come from 1989. Here, Jurová (1993) [

14] assessed data collected by National Committees for social benefit payment, and this identified 254,000 Roma residing in Slovakia. This was 4.8% of the national population, but this estimation is most likely because the Census Commissioner ruling and national committee records on social benefits remain questionable. Vaňo and Haviarová (2002) [

16] then estimated that up to 263,000 (app. 5% of the national population) Roma lived in Slovakia in 1989. However, a comparison of the last 20-year’s Slovak censuses indicates a 60% increase in Romany inhabitants. Finally, Liégeois (1995) [

17] published the exaggerated own estimate of 520,000 Romany in Slovakia, and Šuvada and Slavík (2016) [

18] claim that this figure is often found quoted by foreign authors.

While the fall of the socialist regime in 1989 provided new opportunities for Slovak Roma, on the other hand, it also created problems. The Declaration of Basic Human Rights and Freedoms, accepted by the Federal Assembly of Czechoslovakia on 9 January 1991, secured Roma’s right to decide about ethnic self-affiliation freely. 1991, 2001, and 2011 post-socialist censuses made it possible to identify one’s nationality by self-determination. Only 76,000 people declared Roma nationality in 1991 (1.4% of the Slovak population), 90,000 in 2001 (1.7%), and 106,000 in 2011 (2%). The number of self-identified ethnic Roma has always been far less than the number estimated by experts—official data indicates that Roma self-identification specifies only approximately 25% of Slovak Roma.

The irrelevance of data on the number of Roma from post-socialist censuses is corrected by qualified estimates from sociological surveys published in the Atlas of Roma Communities. These are quoted for 2013 by Mušinka et al. (2014) [

19] and for 2004 plus 2019 by The Government Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities and Institute for Labor and Family Research [

20,

21]. Social surveys have shown a significant concentration of the Roma population within Eastern Slovakia (

Figure 1).

However, even those data do not capture all Roma in Slovakia. Kriglerová and Rybová’s (2004) [

22] estimation from these sources places the number of Roma at 320,000 (6%), and Šuvada (2015) [

23] estimates 450,000 (8.3%). The 2019 Ravasz [

24] Plenipotentiary for Roma Communities most recently specified the Roma population in Slovakia at 440,000 people. The before-mentioned trend in Roma population growth in Slovakia denotes both their absolute number and proportion of the total population; Šprocha (2014) [

8] forecasts a continuing tendency of Roma number increase. Although the middle variant expectation is approximately 590,000 people by 2030 (10.6%), the author does not assume that the Roma population in Slovakia will currently exceed 500,000. The rate of the Roma population in the population of Slovakia has an impact on the economic outcomes of the country. The constant increase in the share of Roma in the country’s population is equal to the increase in the population with low human capital and economic decline through reduced human capital accumulation and reduced growth of per-capita output, notes Azarnert (2010, 2018) [

25,

26].

Finally, the 2019 sociological survey suggests that prognostic scenarios for Roma population development will not be rapidly fulfilled. Moreover, Ravasz (2019) [

24] recently reported that the Roma population growth in Slovakia is gradually declining as a result of improved living conditions. The author explains, “One example is access to drinking water: in the 100 largest communities in Slovakia, 61% of the population has a water supply system. In 2013, it was 48%, and in 2004 only about 36%. We also see a significant shift in other areas”.

3. Data Source and Research Methodology

Investigation of the Roma population’s demographic behavior is challenging because available statistical data on the population’s exact size contain significant errors [

27], and data from official statistics do not reflect the proper demographic status of the Roma population. Besides, the demographic processes of the Roma population in Slovakia can be investigated only indirectly [

28,

29], and therefore we employed a nonstandard approach with a particular survey of statistical data, which retains the character of sample surveys. Podolák (2000) [

30] further reports that research into Slovak Roma reproduction processes is based either on censuses or on various specific sociological and field surveys that are incapable of capturing the entire Roma population. Moreover, the official statistical records fail to provide separate data on the Roma population. Although the Slovak Statistical Office has been recording natural and migratory Roma population movements since 1993, these data are also incomplete through non-inclusion of the entire Roma population (ethnic hiding). While current population censuses capture only a portion of the Roma population, demographic analyses overcome these problems by collecting specific data through sample surveys. Based on the knowledge of small statistical files, conclusions are then formulated with a broader general validity.

Despite the problem of data irrelevance, many authors in Slovakia base their evaluation on data from the Slovak Republic Statistical Office [

11,

28,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. In contrast, other authors employ data obtained from field observations and local government estimates [

15,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Several scientific approaches are also used to define the Roma population and differentiate it from the remaining population. Kertesi and Kezdi (1998) [

41] summarize four distinguishing methods. These methods are based on 1. Groups of people speaking a Roma language, 2. Maintenance of relevant ethnic identity, 3. Categorization by the researcher, and 4. Assessment of the individual and household environment. Although the first two separation methods can be based on self-identification, many Romany do not identify as Roma. This is also confirmed by national census results. The research interviewer can direct the latter categorization procedures by enquiring if the individual disapproves of inclusion as Roma and then look for further verification from the rest of the population. However, different distinguishing methods produce different results, and some researchers, therefore, combine census and survey data [

8,

28,

42,

43].

There are valuable studies on demographic changes in Roma minorities in Central and South-Eastern Europe. Research examining the Roma population based on data from three different sources has provided excellent theoretical and methodological results. For example, many studies integrate a micro-demographic survey of local resources [

27,

38,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Other studies employ national or regional sociological surveys where respondents self-identify or are identified as Roma by a majority of inhabitants [

15,

37,

43,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Finally, others use census information which contains ethnic data [

7,

8,

27,

28,

29,

61,

62,

63].

The demographic status of the Roma population depends on the degree of segregation, socio-economic integration, and the intensity of Romany “ethnic transfer” [

7] into an ethnic population entity. Here, the authors have identified differences in reproductive and demographic behavior in Romany groups with different degrees of segregation in various settlements [

3,

7,

8,

27,

39,

50,

53,

60,

64]. Besides, the 2019 Atlas of Roma Communities [

21] records that only 18% of the total 405,000 Roma live integrated with the majority population, while up to 82% of the Roma population are concentrated within a municipality, on its edges or entirely outside it (

Table 2).

The methodology of our ethnic research commenced with databases compiled from sociological surveys, integrated data from the Statistical Office, and recorded research results. Particular emphasis was placed on municipalities where the proportion of the Roma population is above 80% in the data from the sociological survey conducted in 2019 (

Figure 2). Demographic characteristics related to the Roma population living in settlements with the highest degree of segregation and separation (

Table 2), geographically and socially separated from the rest of the majority, would be monitored in such an allocated population.

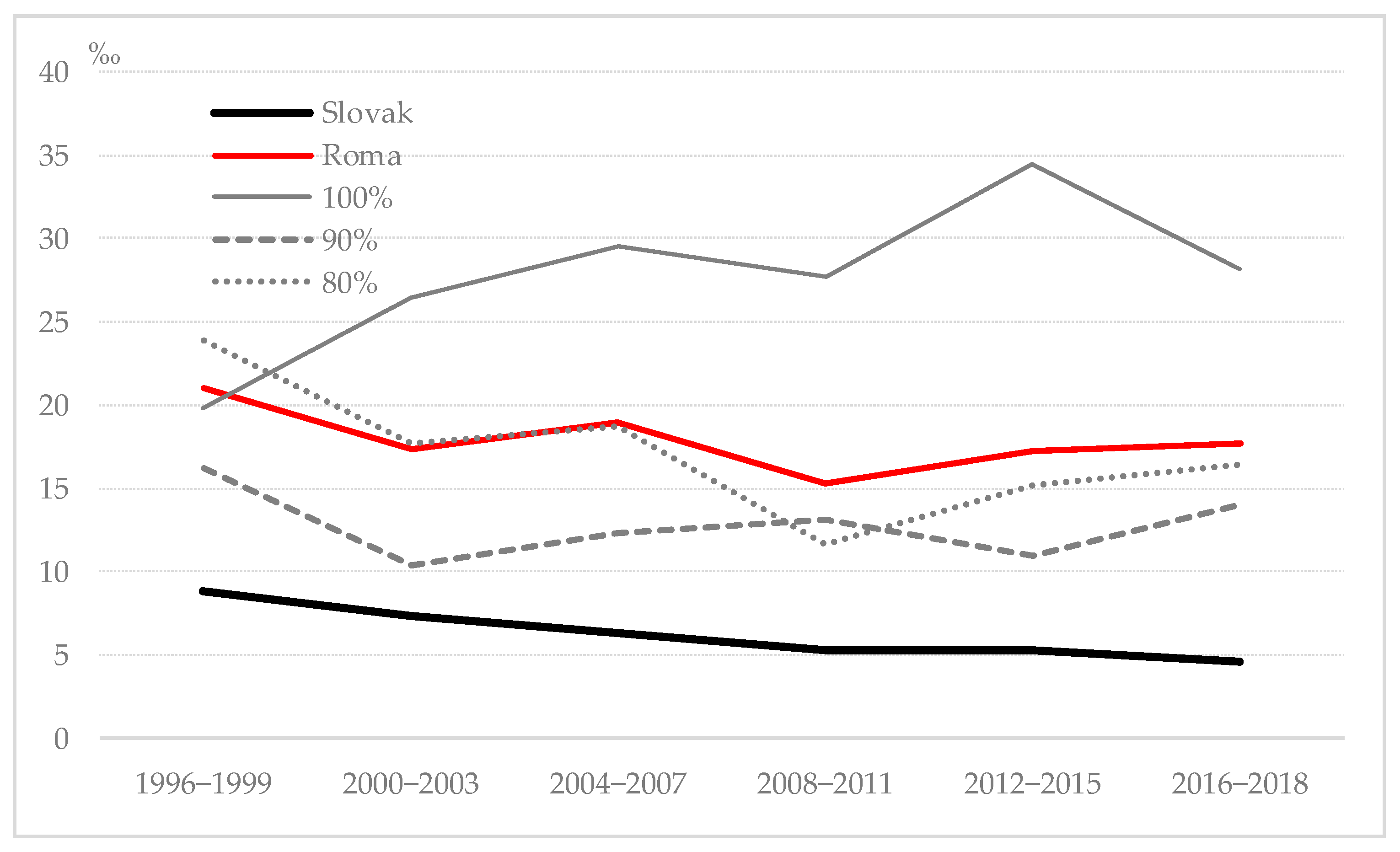

Slovak analysis was used as the proxy for the entire set of segregated settlements, and we investigated the demographic behavior of this sample from 1996 to 2018. Although this risks indicator’s credibility, especially in the initial observation stages, the risk is somewhat alleviated by monitoring the settlements individually and by categorizing the concentration intensity. Municipalities had exceedingly above average fertility and birth rates at the commencement of the survey, which indicates a high Roma population at that time. Changes were examined separately in the categories for 80%, 90%, and 100% Roma concentrations in relevant municipalities dispersed throughout the three NUTS 3 regions and

Figure 2 highlights that these are situated in the 16 Slovak Eastern and Southern districts of Košický, Prešovský, and Banská Bystrica regions. The analysis is based on data from the Slovak Republic Statistical Office obtained from statistical reports of natural population movements and numerical demographic balances from 1996 to 2018.

The data and processes presented in this manner provide a slightly reduced informative value because they are given only for individuals living in the Slovak municipalities selected for Roma concentration intensity. However, demographic characteristics such as age, ethnicity, education, and social status confirm that this is a relatively homogeneous population. Besides, the selected sample’s size is representative and allows generalizations for this highly segregated Roma population. Finally, this study identifies the demographic specifics of the Slovak Roma population over the last two decades and compares them with the Slovak population, not including the studied Roma population.

The claims were verified by examining the relationships between demographic parameters and the degree of Roma concentration in the municipalities of Slovakia (Prešov, Košice, and Banská Bystrica regions) through correlation analysis. The verification was at the beginning and the end of the examined period with the degree of concentration of the Roma population in the municipalities according to the last sociological survey in 2019. This was followed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), which identifies statistically significant differences or similarities in clusters of municipalities according to the degree of concentration of the Roma population on selected demographic indicators.

Correlation analysis showed statistically significant connections between the rates of Roma concentration in municipalities and demographic characteristics (

Table 3). Minor differences are in the development of correlation coefficients, which can be explained by the effect of the demographic situation in Slovakia when the difference between the average age of the Roma population and the population of Slovakia was not significant at the beginning of the observed period when the population of Slovakia was also relatively younger than it is today, especially the population of eastern Slovakia. For ANOVA tests, clusters were created for municipalities according to the degree of concentration of the Roma population. As follows: cluster 10 contains municipalities with 10–19.9% of the Roma population, cluster 20 contains municipalities with 20–29.9%, etc., until finally for the first Anova test cluster 90 contains municipalities with 90–100% (

Table 4), and for the second Anova test, the municipalities with 100% Roma population were separated from this last cluster 90 and cluster 100 was created (see

Table 5). As a result, the first ANOVA test was applied to all clusters 10 to 90 and the second only to the clusters used in our analysis, i.e., clusters 80, 90, and 100. The results indicate that while in the first case the differences between clusters are significant and statistically significant at the level (significance level)

p < 0.001 (

Table 4), in the second case, the differences were small and statistically insignificant at

p < 0.001 (

Table 5), which means that the demographic characteristics in the given clusters were similar with low variance. Verification has shown that the survey of the Roma population in municipalities with a concentration above 80% is statistically reliable.

5. Conclusions

Demographic changes in the Roma population in Slovakia are closely linked to the level achieved in their social integration. There is a wide-spread consideration that global Roma populations are heterogeneous. The largest Roma demographic peculiarities turn out in communities with a significant degree of low economic and cultural development compared to the majority of the population. The traditional and peculiar way of life is characteristic of the Roma people living in settlements with a high degree of segregation and ghettoization. The degree of segregation of Roma localities significantly increases the differences in demographic values between the Roma population and the Slovak population.

However, the processes of segregation and ghettoization of the Roma in Slovakia accelerated again after 1989, and according to Šuvada (2015) [

23], in most cases, it was exclusively uncontrolled and spontaneous segregation. The immediate post-socialist period significantly worsened the overall position of the majority of the Roma population and thus may, to some extent, also have contributed to a decline in the dynamics of promoting changes in reproductive behavior [

10,

23]. At this stage of development, the reproduction of the Roma increased again. The reversal occurs only after changes in Slovakia’s social subsidy policy, which limit various transfers associated with birth and childcare in combination with the difficult position of women and insufficient opportunities to prevent further unwanted conceptions, as argued by Šprocha and Tišliar (2016) [

10].

Where the theory of demographic transition is concerned, the studied Roma population belongs approximately to the late stage of population expansion when the reduced mortality rate is combined with a slight decrease in birth rate and natural increase. According to Kniezevic (2013) [

7], although the Roma population lives mainly on the margins of society, there have been significant demographic changes that should lead from a traditional to more modern Roma society. Compared to the demographic development of the Slovak population, this represents a considerable time lagging in the demographic transformation. The Slovak population is placed in the post-transitional stage of demographic transition, with a very low rate of natural increase. Due to the considerable population growth of the Roma population, it may already be the largest ethnic minority in Slovakia. This is evidenced by studies of the Hungarian population in Slovakia [

91,

92,

93], which point to its significant population ageing with a shallow rate of natural increase. The Roma population is qualitatively different from other minorities, and Podolák (2000) [

30] claims that this is due to its origin, language, way of life, historical and social backwardness, social-class structure, and anthropologically.

Despite the research limitations on studies, some changes in Roma reproductive behavior have been observed in the new millennium. This is especially apparent in the changes from 1996 to 2018 when there was a decline in fertility and birth rates and a consequent slowdown of population growth. Besides, the noted increase in Roma life expectancy signals improved mortality rates and significantly better child death rates. Demographic changes were most pronounced in municipalities with a 100% Roma population. These populations are attended in only two municipalities in Slovakia and produce only 17.5% of the examined population. The changes are also related, to some extent, to changes in Slovakia social welfare policy. Furthermore, social security benefit allowances are an essential part of family income and maybe influencing reproductive strategies, especially for segregated Roma women [

62]. Demographic development in other “almost-only-Roma” municipalities remains almost the same or with slight changes.

While this research has faced limitations and prejudices, it offers valuable insight into the main features of demographic behavior and changes in Roma population development. The presented study provides a solid foundation for future exploration. Although this contribution has no claim to complexity from either a historic or problem-solving perspective, its focus and scope contribute to clarifying connections in the demographic characteristics of the Roma minority in the Slovak Republic. It also demonstrates the demographic behavior of the Roma population and points to the fact that its development is greatly influenced by the degree of segregation and differentiation in economic, social, and living conditions. However, it is necessary to realize that not every segregated settlement in Slovakia shows significant demographic differences from the majority population. The Slovak Roma population is heterogeneous in integration, with the latest 2019 sociological survey identifying that almost 82% of the Roma population is not integrated and living in settlements with a high degree of separation from the general population.

Demographic analysis indicates that the Roma population is undergoing slight changes in reproduction, and although reproduction remains within a solid traditional framework, the changes are an initial indicator of socio-economic integration. Finally, the developments noted in recent decades indicate that the Slovak Roma population is slowly but surely changing the intensity of fertility, birth rate and mortality, and these have an impact on gradually reducing population growth, especially in purely Roma communities. Consequently, a better understanding of Roma demographic behavior is essential for any forecast about the demographic and economic future of Slovakia. It is necessary to stress that this community should experience a decline in population growth due to sustainable development in the country’s economy. Otherwise, according to Azarnert (2018) [

26], an increasingly growing population with lower skills, productivity, and labor force participation relative to the majority population will generate a threat for the prospects of sustainable economic growth in Slovakia, as has been broadly argued about the minority populations of non-European origin in Western Europe.