4.1. Greenery in Panoramas and Views from Housing Settlements in the Waldenburg Area

The hilly and mountainous terrain of the Waldenburg area made it possible to create special landscape effects. Housing estates were built at the foot of towering peaks—small ones like Wilhelmshöhe (Gediminas Hill) and quite impressive mountains like Schwarze-Berg (853 m above mean see level, Borowa) or Hochwald (850 m, Chełmiec)—and on the edge of old villages and developing mining towns (usually neighboring with vast areas of private forests that were mostly owned by the Hochbergs but sometimes owned by the state. The artists were perfectly aware of the possibility of exploiting the landscape values of the area. Ernst May knew the surrounding mountains and villages and made sketches of them in his sketchbook (see

Appendix A, A6). Most of these settlements were created as special landscape complexes. They were created as separate units that were carefully integrated into their environment. This was manifested in the conscious and extremely careful shaping of the panoramas of the complexes. This problem was raised, among others, by May himself when discussing the issues of housing estates design. He emphasized the necessity of subordinating an urban complex to a dominant feature. In most cases, these were already existing church towers in neighboring villages. This is how the housing estate in Gottesberg was designed. In the settlement Stadtparksiedlung (Gaj), a chapel was to be built as a dominant element. The housing estate on Sandberg (Piaskowa Góra) in Salzbrunn was subordinated to the dominant of the Catholic church, and the housing estate in Dittersbach (Podgórze) near Waldenburg was subordinated to the dominant elements of the Lutheran church. The designed housing estates were adapted to the existing development method in the neighborhood, its intensity, and the height of the buildings; they received similarly shaped composition nodes and a dilution of the building fabric in the form of squares and street extensions. This created an analogous urban pattern that imitated the spontaneity of the settlements’ development in the landscape. The settlements built by or in cooperation with Schlesische Heimstätte show that the best results were achieved when the topography was preserved and followed. Small slopes, escarpments, or depressions gave the settlements a natural and picturesque landscape. The location of settlements on hills or slopes gave views of the surrounding panorama.

Hermann Jansen (see

Appendix A, A7) took particular care to exploit these opportunities [

47,

48]. When, after the First World War, the city authorities of Waldenburg independently made another attempt (after the foundation of Neustadt; Nowe Miasto) to build a large residential district, they asked this well-known Berlin academic for a design. In the arrangement of Hartebusch Siedlung in Waldenburg, Jansen repeated the principles of spatial organization used in the Berlin housing estates of his design; see

Figure 1.

However, the specific topographical conditions dictated special solutions. Due to a shortage of land in the neighborhood of Waldenburg, it was decided to locate the housing estate on this exceptionally steep slope. This imposed a kind of terraced layout on the whole settlement; see

Figure 2.

Along the main road, the estate was enclosed by a row of multi-family buildings. Along the main streets, the composition nodes were regularly arranged in the form of squares and terraces connected with the largest three-story multi-family houses, from which one could admire the panorama of Waldenburg and Altwasser (Stary Zdrój, Jastrzębie-Zdrój, Poland) [

18] (p. 247–264).

Perhaps it was this successful settlement that inspired Ernst Pietrusky (see

Appendix A, A8) [

49,

50,

51] to shape a similarly situated settlement in Nieder Hermsdorf (Sobięcin Dolny); see

Figure 3a. Unfortunately, most of the planned viewpoints were not completed. The project of Ernst Pietrusky’s housing estate in Nieder Hermsdorf was selected as a result of a contest announced in the magazine

Schlesisches Heim [

37] (pp. 8,68,111) [

52,

53,

54,

55]. The architect based his conception on a strict representation of the terrain’s shape; the irregular lines of the streets were running horizontally. Probably this naturalness and the use of a high building density for a housing estate of this type were decisive for the choice of this solution. As in the case of the settlement on the slopes of Wilhelmshöhe in Hartebusch Siedlung, squares were to play particularly important role in the layout of the Nieder Hermsdorf housing estate, including appropriately placed squares at the end of the streets in the form of viewing terraces opening onto the valley of the stream flowing through the village.

The early modernist housing estates of the Waldenburg agglomeration were formed as unique landscape complexes that were carefully inscribed into the mountainous landscape of the region. Subordinated to selected dominants, with carefully shaped accents in height and volume, they revealed themselves in interesting panoramas and views. They were enclosed by greenery that separated them from the neighboring areas. Viewing points were planned within the residential complexes, where views of old villages, mountains and hills were given between the houses and rows of trees. Inside the housing estates, green alleys and gardens surrounded the buildings, separated the sub-units, and contributed to the compositional skeleton.

4.2. Greenery in the Settlements: Squares, Green Spaces, Tree Rows and Alleys

In the design of this period, the role of public greenery was appreciated, both in larger areas in the form of parks and huge squares and in the form of street rows.

On the Hartebusch estate, Hermann Jansen, in his typical fashion, used green strips to separate the different levels of the housing to accentuate the main public spaces and to emphasis the composition. Between the two main streets, which run horizontally from side to side, a green public area with squares and playgrounds was laid out in the middle of the estate. They constitute the skeleton of the settlement, which is emphasized by the grouping of multi-family buildings and the creation of a green space between them, Eichenplatz (i.e., Oak Square, now Zawisza Czarny Square), where the architect decided to preserve the centuries-old oak trees. Below the two main streets, two levels of parallel streets were designed, and above the main streets, one was designed. To the north, at the end of the streets, Jansen planned to leave a green belt in a shallow ravine, subordinated to the compositional axis created by the water tower visible over the housing estate. On the other side of this green space on the north-eastern slope of the hill, he designed the second part of the housing estate in a similar terraced arrangement.

Another version of the project was prepared by Otto Rogge (A9]) (

Figure 3b), a building advisor at the municipal office [

18] (pp. 18, 247 et seq.) [

56]. He took even more care to preserve the existing valuable trees and arrange new plantings along the estate streets. The lower main street of the estate, the original village road, is lined with rows of lime trees; see

Figure 2 and

Figure 4. In the highest part of the settlement, there is a large square called Buchenplatz (i.e., Beech Square or Gediminas Square), where beech trees are protected. All squares and plazas of the settlement were connected to extremely steep pedestrian walkways that are, in some places, arranged as stairs running up and down the hill. At most of them, tree rows were designed to highlight their course. The architectural lines were also planned to be highlighted by connecting the free-standing buildings with rows of trees. From the first stage of construction, tree rows were planted along the streets; for this purpose, specific species were chosen, e.g., the lime alley was supplemented with faster-growing chestnut trees. The centuries-old oak trees were preserved, but the beech trees were unfortunately partly cut down.

In the arrangement of the greenery, familiar forms of rows, avenues, and squares were used, sometimes extending like a small park. The special role assigned to the greenery was different. In the final effect, the housing estate gained a system of greenery, co-creating the basic urban composition. Successive lines of buildings on the slope were separated by strips of greenery that formed a background for them. The rows emphasized the rhythm of the urban structure. The green spaces stretching down the slope and continued by the trees on the steep pedestrian approaches were used to emphasize the main compositional axes of the urban complex.

Ernst May had a slightly different approach to the design of the green spaces in the neighborhood when he planned the housing settlement—Stadparksiedlung [

18] (pp. 280–290); see

Figure 5.

It was to be a residential complex reminiscent of the villages near Waldenburg, with buildings appearing to be spontaneously developed. The greenery introduced into the layout had to emphasize this character by creating groups of trees and bushes reminiscent of those spontaneously growing by the roads and main squares of the village. The concept of the settlement resembled the construction of Neustadt or the settlement Hartebusch—the creation of a completely independent urban organism. The land to be developed was located behind a mountain railway viaduct that was far from the town and surrounded by forests on all sides. The solution proposed by Ernst May took the shape of the land into consideration (levelling was kept to a minimum). The two main roads run inside the area along a closed lenticular circumference. Small, semi-detached, single-family houses were designed on both sides of the streets. The plots marked out on both sides have a variety of shapes. The main square, as well as several small squares inside the settlements, was planned. The complex was made to have charming alleys. There is no rigidity, there is variety, and each section has a different curve due to the terrain. The narrow streets are winding, almost like country paths. Diverse groupings of buildings were created around squares, and accents and compositional nodes were created despite the use of identical architectural objects. The complex is an example of implementation of the “garden settlement” concept in the form of a village-like unit with greenery that imitates groups of natural vegetation. The idea was based on the creation of a small semi-rural center—a square with a school and a chapel in the north-eastern part (from the town side), closed on two sides with two-story frontages, with passages in the that which could satisfy the needs of the inhabitants. It also had its advantages in terms of the landscape. The introduction of the square created a hierarchy of space and gave independence to the settlement that was thus gaining a rank equivalent to the neighboring industrialized villages [

45,

57,

58]. Both the main square and all small squares of the settlement were filled with greenery, though some of them only with low levels of such. However, the basic greenery in the settlement was planned to be private fruit and vegetable gardens with flowers, thus creating a rural landscape. The greenery complemented the buildings, and together they formed a housing unit that very closely copied the appearance of the neighboring medieval villages.

It was also possible to combine these two ways of using greenery of traditional composed forms and imitation wild vegetation. In the unusually careful design of the Nieder Hermsdorf settlement (

Figure 3a), Pietrusky was inspired by both the propositions by Jansen and some of May’s ideas in the design of the greenery. The concept was based on keeping a road connecting an orphanage (which had been erected in the former village at the end of the 19th century) as the main street, with a folk house designed in the southern end of the settlement on a hill, to which a line of stairs in greenery would lead; this settlement was to be preceded by a triangular square that constituted the settlement’s main square [

37,

55] (p. 68). Ernst Pietrusky planned three-story buildings with commercial premises on the ground floor. Thus, the square was to constitute the functional and spatial center of the settlement. The remaining streets were laid out along curve lines in accordance with the slope’s contours, crossed with streets running down the slope of the terrain [

54]. The irregular course of the streets introduced diversity and a high individualization of space, despite the use of typical buildings. The use of small squares was to highlight the rank of selected objects, and, in the final version, it was used to create distinctive places where the life of the settlement would concentrate.

The housing settlement was conceived as a compact and closed urban layout whose composition was based on emphasizing the main axis, within which the center of the housing settlement—clearly marked and emphasized with the use of higher buildings—was developed. The streets and narrow pedestrian passages were to be planted with tree rows. Numerous green squares enriched the layout. In the eastern part of the settlement, at the foot of the slope, a rectangular elongated square was planned with a small square connected to it at the corner, and an irregular square in the bend of the street was planned to be above it. In their vicinity, at the crossroads of the streets, a small rectangular square was to be the foreground of the kindergarten and school building. In the original version, another large rectangular square with a bay was planned at the south-western end of the settlement, as were squares at the ends of the streets on the western side—one of them with a viewing terrace. There were also to be two large squares on the settlement, a kind of small park sheltered by a screen of trees. They were located within the quarters of single-family housing on large plots extending the public greenery with private gardens; see

Figure 6.

The larger of the squares was adjacent to the steps leading up to the folk house on the settlement’s main traffic route. The project was not fully implemented. However, during construction, the greenery in the settlement was introduced from the beginning in accordance with the plans of project. Lime, maple, and chestnut trees were planted along the streets. Some of them also appeared in private front gardens introduced here [

59]. As in Hartebusch Siedlung, a lime-poplar alley [

60], which ran in the neighborhood and was later supplemented with maples and old pines on the top of the hill, was preserved. A centuries-old yew tree at the northern end of the settlement was also treated with due respect. In 1925, the 19th century park (Volks Park) in the north of the settlement was redesigned. Within several years, the settlement became a green enclave, which, of course, did not reduce the health problems of its residents. From the very beginning, the biggest inconvenience for the housing settlement was the extremely close vicinity of the coking plant and chemical works. Already in the 1920s, the planners working on this housing estate addressed queries to the local authorities about the acceptable rates of air pollution in the residential areas due to the proximity of the coking plant and the chemical works [

61]. It is possible that the Nieder Hermsdorf settlement was one of the first places where the issues of industrial pollution started to be addressed.

The greenery system of the Nieder Hermsdorf estate co-created the compositional skeleton of the residential complex. It marked the main compositional axis and emphasized the most important urban interiors. The park with a garden restaurant, amphitheater, and music pavilion, as well as spacious green squares, provided areas for rest and recreation. Green front gardens in front of the service buildings and kitchen gardens created a compact green environment for development. Particularly interesting was the incorporation of private gardens into an overall ensemble with green areas accessible to the public and decorated with lines of footpaths. This created an impression of the naturalness of the greenery planted on the estate. Another important aspect was the respect for the existing trees and the park complex, as was the case on the Hartebusch estate.

Similarly shaped green squares, parks, streets, and alleys were designed in other housing settlements built in the region of Waldenburg in cooperation with Schlesische Heimstätte. Squares, some of which were to be planted with trees and others of which were only to be planted with low greenery, were an integral part of the layout. In the settlement planned as an extension of Gottesberg (1919), Ernst May, apart from the square functioning as a market, also designed a triangular green square in the middle of the development surrounded by single-family terraced houses [

62]. In the competition-winning design of the housing settlement in Neu Salzbrun (Nowe Szczawno) (1920), Theo Effenberger, already a well-known designer from Wrocław and the author of the housing settlement in Pöpelwitz (Popowice in Wrocław) (1919) (A10]) that was under construction at that time [

63,

64], introduced an irregular square surrounded by compact building frontages at the end of the axis of the layout—a street emerging from the former communication junction in front of the railway viaduct [

18] (p. 357) [

65]. In the second of the settlements planned in Rothenbach (Gorce) for the Schlesische Kohlen und Kokswerke company, May and his teammate Bussmann proposed a square in the center with a semi-circular outline, a school, and a church (or folk house?), surrounded with a park (1921) [

66]. These complexes were not realized. In Weiβstein (Biały Kamień in Wałbrzych), the designers chose solutions with squares in the center of the housing settlements divided into workers’ gardens (1924) (see

Figure 7) [

18] (pp. 325–337).

Squares were important green elements used in early modernist housing estates. They took a different form than those from the 19th and early 20th centuries. They often had an outline of an irregular triangle or were not of any size at all. They accompanied not only important service buildings but also often diversified residential developments, including single-family ones. This type of solution imitated natural groups of vegetation.

Tree rows were equally important for composition. In the case of the housing settlement in Sandberg (1918–1919), rows of lime trees and chestnut trees on both sides of the street constituting the basis of the complex emphasized its character; see

Figure 8. Using a cul-de-sac, which resembles an agricultural homestead, it skillfully imitated the development of a typical mountain village stretching along the green banks of a creek [

67,

68]. The housing settlement in Gottesberg was enriched by street bays with rows of lime, maple, and chestnut trees; see

Figure 9. In the above-mentioned Effenberger’s project, the compositional skeleton was to be the ring street (Ringstrasse), with a one-sided development on the outer side of the housing complex surrounded by a tree row, from which the Salzbach (Szczawnik) valley would be visible; on the other side, the housing settlement on the Hochwald Mountain would be visible. On both housing settlements in Dittersbach (Podgórze in Wałbrzych)–Neuhäuser Siedlung and Melchior Siedlung (1920), which was designed by Ernst May and adapted in the municipal office by Daehmel [

18] (pp. 291–311) [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]—one could enjoy the views of grand alleys. At the Melchior shaft (after the war, it was renamed the Mieszko shaft), these were lime alleys on both sides of the railway tracks (

Figure 10), while at the second settlement, the old lime alley (Neuehauser Allee) was preserved, running from the village near the Catholic church up the slope towards the castle and the manor in Neuhaus (Nowy Dwór) (

Figure 11). Like in Nieder Hermsdorf, front gardens separated by rail fences and rhythmically planted trees appeared in front of the houses in both these settlements. They were also created in subsequent small settlements in Konradsthal, Nieder Salzbrunn, and Adelsbach near Waldenburg (Konradów, Szczawienko, and Struga) (c. 1923–1925) [

18] (pp. 358–377).

Avenues and rows of trees, both the preserved and carefully protected 19th-century complexes and the new ones, constituted an important element of the urban composition of the residential complexes under discussion. In this case, as in the design of the squares, in addition to continuing the form of a straight avenue and row and a regular roundabout, planting in the form of short rows, which were non-rhythmic in character and imitated natural trees, was sometimes used.

The preservation of some green spaces within the designed housing settlements was also required for reasons of economy and knowledge of the influence of physiography—the topography of the terrain, the presence of watercourses, sun exposure, problems with cold air flow, and ventilation. This could already be seen in the earliest post-war project by Jansen, where the architect left green ravines that were difficult to level and are threatened by cold air flow. Similarly, he approached May’s physiographic issues with great emphasis, probably largely influenced by Raymond Unwin. In mountainous areas, the consideration of rules was particularly important, which he highlighted in his articles. A characteristic feature of his projects was the precise adaptation to topographic and physiographic conditions. Taking advantage of the terrain’s shape in addition to improving the microclimatic values, significant savings on levelling works during construction usually resulted in a smooth curvilinear line in the urban composition [

66]. Consequently, the settlements had small interiors, and the inhabitants enjoyed various views from successive places along the streets. In the Waldenburg region, the settlements built in this period, usually in difficult-to-develop areas with steep slopes, were given a layout based on running streets parallel to the slope contour. In the case of the Dittersbach housing settlements, the main streets were laid out in wide arches that formed serpentines and horseshoe shapes surrounding green spaces. In May’s designs (Stadparksiedlung), attention was drawn to the extremely precise mapping of the terrain along the streets, which were thus laid out along a winding line. A completely new theoretical problem was the design of settlements on steep slopes (Rothenbach) [

66]. May drew on limited design experience to solve housing estates in mountainous areas. There were no patterns of regular village buildings, so he drew some inspirations from the towns of the Sudeten foothills, e.g., Silberberg (Srebrna Góra) [

73] and probably also from Gottesberg (which Ernst May known from the time of design). He developed a layout following the contours of the hill, with farm buildings at the gables of the houses or in a separate line at the back of the plot.

In the design of early modernist housing estates around of Walbrzych (

Figure 12), public greenery was of particular importance. It was arranged in a way that imitated the forms existing in the landscape. Old alleys were preserved, and the design of this form of greenery, clearly visible in the landscape, was continued. This emphasized the traditional communication and cadastral structure. Tree rows served to strengthen the rhythm of the buildings. Larger greenery complexes marked the axes and composition nodes of these urban layouts. At the same time, many elements imitating natural groups of roadside and village greens were introduced. They gave the whole arrangement a character of spontaneity.

4.3. Employee Gardens, Tradition, and Design

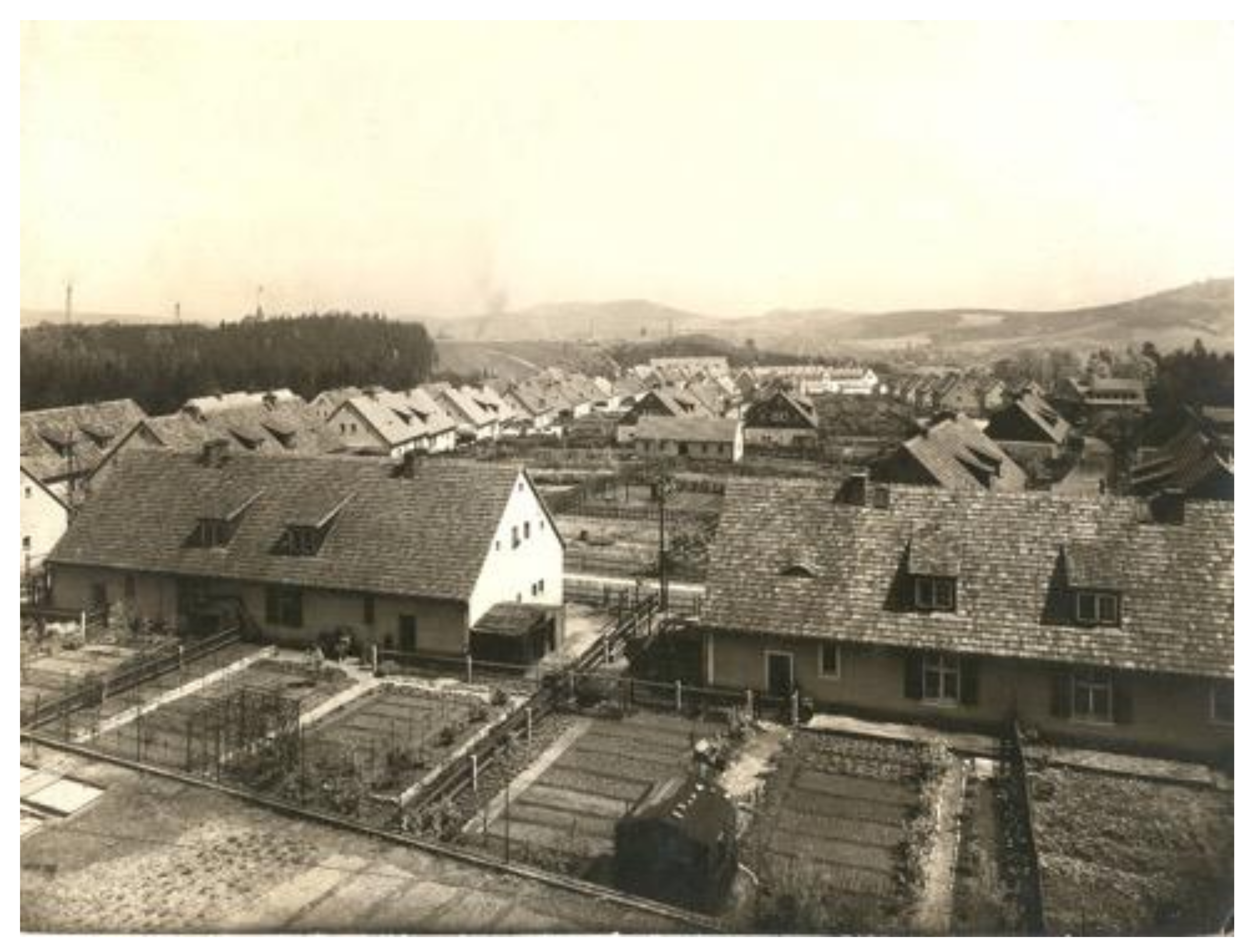

Another particularly important issue was the provision of housing settlements with home gardens (Kleingarten) or workers’ gardens (Schreibergärten) according to sociological assumptions and government guidelines (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). This was an idea developed based on government recommendations of the time, but it had an old tradition in the Waldenburg district. Initially, when the initiative in housing matters belonged to the owners of mines and factories, as well as the railway authorities that wanted to provide manpower in their plants, patronage settlements were established. These mostly small complexes, consisting of several houses, were equipped with a common area, a playground, small social facilities and workers’ gardens. The entire housing settlement area was divided into small plots. Wooden sheds, pigsties, and dovecotes were built among them. Additionally, in the case of municipal or communal multi-family houses, at least some of the flats were equipped with workers’ gardens, as was the case in the new districts of Waldenburg–Neustadt (1904) or the new part of Weiβstein (1904), where the uninvested lands were allocated for this purpose for a short period of time (

Figure 15).

To a large extent, the functional solutions of the settlements had to be derived from the layout of rural houses, as the population was usually comprised of first-generation migrants from the countryside. The idea of a house with a garden for each family, derived from Howard’s theory and implemented by Unwin (in whose studio May worked during his internship in England), was a response to social needs. In earlier periods, the need to cultivate at least a piece of land was secured by providing each flat with a workers’ garden. In the projects of the Schlesische Heimstätte studio, both concepts were combined. In the early modernist housing settlements, gardens could have the character of agricultural facilities with a considerable area of 1500–2500 m

2—as in the case of the housing settlement on Sandberg, which initially (similarly to the housing settlement in Goldschmiden (Złotniki in Wrocław)) was to be mainly rented to agricultural workers. In Gottesberg, each flat that was located in the first row of two-story single and semi-detached buildings with single-story connectors was provided with a large garden (450 m

2) behind the buildings and with sheds in the connectors between the houses [

74]. In Stadtparksiedlung, gardens varied in size (200–500 m

2), and in the Nieder Sobięcin settlement, the differences were more significant depending on the type and location of buildings (130–350 m

2). Most often, the size of plots exceeded 200 m

2, as in the settlements in Rothenbach (200–300 m

2) or Dittersbach–Neuhäuser Siedlung (200–300 m

2). The smallest were plotted for multi-family housing settlements in Melchior Siedlung (100–150 m

2) and Gottesberg (70 m

2), while in Weiβstein, they slightly exceeded 50 m

2. The plots were carefully planned and enclosed with fences. This created checkered or fan-shaped green arrangements. In the gardens, the outbuildings—that were designed together with the remaining buildings in many housing settlements (e.g., in Dittersbach, Weiβstein, and Konradsthal)—were erected. Vegetables and flowers were grown. In most settlements, poultry and even domestic animals were also kept. However, in some cases, it was strictly forbidden even to have dovecotes (Nieder Hermsdorf). The attachment to this form of contact with nature and relaxation after working hours is evidenced by the fact that the probably planned green spaces in the housing settlement Hartebusch, as in all previous Jansen projects, were parceled and changed into gardens; the same happened at the end of the 1920s and 1930s (in the Waldenburg agglomeration, only two pre-war housing settlements had public green spaces).

Attempts were also made to ensure an attractive appearance, a good level of care of gardens, and an increase in production efficiency. These goals were achieved by establishing companies that promoted knowledge in the field of gardening and publishing magazines addressed to users of small home and working gardens [

16,

75].

Home and working gardens became the most important characteristics of the housing estates of that period. They provided for the needs of the population from the countryside who were accustomed to cultivating the land and keeping domestic animals. Such facilities also sought to establish social habits. The need to ensure stress-relieving recreation for the miners, which had been fulfilled by visits to taverns or handicrafts (e.g., hosiery making in the Waldenburg region), could be replaced by gardening. It also had an economic aspect, simply supplementing the inhabitants’ diet and raising the general level of nutrition, which turned out to be particularly important in the period of the “great crisis.” It was also important to transfer some of the work of cleaning and developing the estate to the residents. This could have decisively accelerated the process and rapidly improved the natural qualities of the housing area.