Abstract

Although the issue of corporate culture has been taken over and addressed in the literature from various perspectives, there are very few researchers about the role of leadership and motivation in it, respectively very few researchers have addressed them as important components of the international company’s corporate culture. The present paper aims to point out that leadership and motivation can be perceived as important aspects of the international company’s corporate culture. The object of the investigation was an international company (situated in Italy) and its five subsidiaries (situated in Italy, Czech Republic, Germany, and Turkey). As the main research method, there was chosen the method of the questionnaire survey, which was attempted by all the company’s employees (totally 270 respondents). The questionnaire was divided into three separate, but logically related parts—leadership, motivation, and corporate culture, and submitted to two groups of respondents—the company’s management and its employees. In total 11 hypotheses were formulated and further evaluated by the methods of Pearson Chi-square Test, Fisher’s Exact Test, Cramer’s V coefficient, Kendall rank correlation coefficient, Eta coefficient, Spearman coefficient, Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon W statistics, Kruskal–Wallis test, and Friedman’s test. The results of the research have proven that leadership and motivation are important parts of the corporate culture.

1. Introduction

Academics and researchers as well as practitioners have reviewed sustainability from various perspectives [1,2]. Academics acknowledge it as an approach that is adapted to meet current requirements while developing capabilities that can help focus on the future [3]. The concept incorporates three dimensions, namely, the economic, social, and environmental dimension [4]. While the economic dimension of sustainability is seen as the most desirable because it provides financial strength and avoids conditions led to an early demise of the business [5], the marketing literature discusses sustainability and highlights its role in creating opportunities and driving company’s performance by taking up social initiatives understood as corporate social responsibility [6]. The role of operations in making a business perform on the parameter of sustainability has been discussed as a determinant of a company’s ability to produce or deliver efficiently [7]. According to a few researches, a company can perform better when its activities are performed taking into account all of the three dimensions of sustainability [3]. Companies are trying to create a balance among these three dimensions of sustainability to secure a safer future for their business [8].

Despite the fact that the present time “pressures” the companies in the spirit of creating and maintaining an effective and especially sustainable long-term orientation, many companies are still unable to meet respectively achieve this aspect. The response to the principle of sustainability and the pursuit of the characteristics and scope of sustainable goals of the company, must clearly and above all, significantly affect the competitiveness itself, and it can be said of the survival of company as such.

The Sustainability Leadership Institute (2021) defined sustainability leaders as follows: “individuals who are compelled to make a difference by deepening their awareness of themselves concerning the world around them. In doing so, they adopt new ways of seeing, thinking, and interacting that result in innovative, sustainable solutions” [9] (p. 3).

Nevertheless, other leadership approaches are welcome, such as responsible leadership [10].

The issue of leadership and motivation continues to grow in importance and is becoming increasingly popular and discussed [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Unfortunately, almost none of the researches are aimed at the interrelation between the leadership, motivation and corporate culture; they are focusing mostly on two from the three mentioned attributes. This paper deals with the analysis and classification of these key areas of international management and entrepreneurship and at the same time tries to summarize individual knowledge and recommendations obtained from the subject, to which has been and still is paid great attention of individual authors and experts in the given field.

The research in question is the result of previous research carried out by the authors of the paper in the conditions of an international company where the intention was to find out how motivation and leadership affect the corporate culture of the company, as well as to find out the extent to which cultural specifics influence the applied leadership style and motivation [19,20]. The surveyed international company agreed with the publication of the results of our research, considering them as an interesting and suitable base for further research and its application in the practice. However, the company did not wish to use its name in the paper; therefore, it was redacted.

The paper is divided into four main sections, where the Literature Review offers the most important and relevant studies published in the given field focusing on terms related to our research such as leadership, leadership style, motivation, corporate culture and international company. Following part, the Materials and Methods present the dataset of analyzed companies and describes the used methodology as well as formulated hypotheses that create a base for our research. The third part of our paper offers Results as well as Discussion, presenting the most important findings and results of our research and the testing of the hypotheses. The Conclusions underline the main outcomes and present the limitations and future focus of the research. The submitted paper addresses a gap in the literature and research by exploring the leadership and motivation as aspects of the corporate culture of an international company.

2. Theoretical Background

Leadership is one of the most basic and at the same time the most important functions of the company management, which besides planning, organizing and controlling helps to achieve the goals. While the functions of planning, organizing, and controlling are some sort of “latent cocoons” which have to be “awakened” and brought to life, the function of leadership is precisely responsible for this activity [21].

There are even innumerable different definitions of the term of leadership and yet there is still some “misleading” information about it. Many of different authors such as [22,23,24,25,26,27] disagree and seek to refute these claims and explain them in more detail. The most well-known and basic definition of the term in question is the definition given by [11], to which lean also authors such as [28,29,30]. According to this definition, leadership can be characterized as the ability or process of influencing people in which the manager, using his power, seeks voluntary and willing participation by subordinates in achieving group goals, and thereby satisfying their own needs.

Up to [9], there can be distinguished exactly three main approaches to better understanding of leadership-1. The Trait/Style school, which focuses on the characteristics or approaches of individual leaders [31,32]; 2. The Situational/Context school, which focuses on how the external environment shapes leadership action [33,34]; and 3. The Contingency/Interactionist school, which is about the interaction between the individual leader and his/her framing context [35,36].

Leadership takes various forms. The leadership styles are defined, e.g., by [37], who distinguish between three leadership styles, namely, the authoritarian (autocratic) leadership style, where the leader provide clear expectations for what needs to be done, when and how it should be done, and where the leadership is strongly focused on both, command by the leader and control of the followers; the participative (democratic) leadership style, which was by the time found as the most effective leadership style, and which is characteristic whereby the leader offers guidance to group members, but at the same time he also participates in the group and allows input from other group members; as well as the delegative (laissez-faire) leadership style where the leader offers little or no guidance to group members and leave the decision-making up to group members. Based on the written, it can be stated that these leadership styles are the most frequent and most cited. Further, we can mention the Likert leadership styles, where we can distinguish between four leadership styles—exploitive authoritative leadership style where the leader has a low concern for people and uses such methods as threats and other fear-based methods to achieve conformance; benevolent authoritative leadership style, where the leader adds concern for people to an authoritative position; consultative leadership style, where the upward flow of information is still cautious and rose-tinted to some degree and where the leader makes genuine efforts to listen carefully to employees’ ideas; and participative leadership style, which represents a level where a leader makes maximum use of participative methods, engaging people lower down the organization in decision-making) [38]; the Blake Mouton Managerial GRID, which is based on two behavioral dimensions—Concern for People (where the leader considers team members’ needs, interests, and areas of personal development when deciding how best to accomplish a task) and Concern for Results (where the leader emphasizes concrete objectives, organizational efficiency, and high productivity when deciding how best to accomplish a task) [39]; Transactional Leadership Theory, which occurs when a leader engages in an exchange process with subordinates [40]; Transformational Leadership Style, which associates with changes in the beliefs, values, and needs of followers [41]; also, servant Leadership, Resonance, and others [42,43,44,45,46]. As leaders in charge of employees are expected to set a good example, protect their employees, and not only achieve company targets [47]. It is realized by every leader that there are techniques to be able to improve the company performance so that it can be improved by increasing motivation of employees and then the employees can carry out their duties following the rules and direction [18].

“It is not hard to state in a few words what successful leaders do that makes them effective. But it is much harder to tease out the components that determine their success. The usual method is to provide adequate recognition of each worker’s function so that he can foresee the satisfaction of some major interest or motive of his in the carrying out of the group enterprise”[48] (p. 174).

According to [49], responsible leadership is exactly the leadership behavior which focuses on the interests of the business as well as other stakeholders. It must be also mentioned, that this form of leadership has effectively compensated for the shortcomings of traditional leadership forms and is of substantial significance to enhancing corporate reputation and maintaining the sustainable development of companies, and at same time of the society as whole [50].

Based on the written, the efficiency and success of leadership depend not only on the professional abilities and skills of the manager himself but also on the effectively and appropriately chosen way of motivating employees, because only a properly motivated worker is also a good and faithful worker who helps to achieve the set goals [19]. Practice and experience confirm that the success of managerial work depends largely on how much attention managers pay to their employees, how they can recognize their needs and expectations and motivate them to achieve high performance [51,52,53,54]. The issue of motivation itself, as well as its forms and components, is dealt by several authors, of which only a few are mentioned, such as [55,56,57], who explain motivation as a person’s willingness to make significant efforts to achieve the goals of an organization, conditional on meeting the individual’s own needs. However, to do so, they need three basic elements, namely, the effort of the individual, his individual needs, and the aims of the organization. By other words, Ref. [58] explains the motivation by the fact, that it refers to everything that a person experiences, tries to achieve the ideals or ideas. According to the mentioned author, motivation can be understood as an internally activated behaviour, which is performed spontaneously and without compulsion, or as an externally activated behaviour caused by an external agent.

Even though in general, we can talk about two big groups of Motivational—the Content Theories of Motivation (represented by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs [59,60], Alderfer ERG Theory [61], Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory [62], and McClelland’s Human Motivation Theory [63]) and Process Theories of Motivation (represented by the Equity Theory [64], Expectancy Theory [65], Reinforcement Theory [66]), in case of work motivation is applied mostly to one of them—the Process Theories of Motivation, which try to explain why behaviors are initiated.

While no “grand unified theory” of motivation has yet been proposed [67], several core theoretical perspectives can be identified [68], that in principle give leaders a sophisticated set of tools to promote their employees’ motivation. As one of those core perspectives on motivation can be mentioned the goal-setting theory [69], further the Expectancy theory [65] and the Job Characteristics Model (JCM; e.g., [70,71]) which principles are—the higher the goals the employee sets, the higher are his expectations, the more motivated he is. The only expectation is the third mentioned perspective, which is built on the assumption that certain structural characteristics of work tasks prompt psychological states that are the prerequisites to high levels of job satisfaction and work motivation [72].

As it can be seen from the paragraph above, as well as it is also stated by [73] the literature is almost overlapped with the research on motivation. While in the past, the mission of the leader, especially regarding the employee motivation, was not clear and completely unambiguous [74] and leaders frequently undermined the importance of developing an effective relationship with stakeholders including the employees [75], nowadays we understand that leaders should implement different strategies that are customized to individuals, their desires and needs—some employees are simply motivated by job security, others by clear company policies, power, recognition, compensation, or there are also employees who are just enjoying what they do, and that is their motivation [76].

When defining and explaining the concept of motivation, it should be kept in mind that motivation and stimulation are not identical concepts. While motivation, as Ref. [77] argues, is an expression of the fact that in the human psyche, there are specific, not always fully realized internal motives that motivate a person and his activity in a certain direction, activate and maintain the induced activity in that direction, so the stimulation is an external influence on the psyche of a person as a result of which there are some changes in his activity. The basic difference between motivation and stimulation is therefore that stimulation is an effect on the psyche of an individual from the outside (most often caused by another person’s activity) and not from the inside as is the case with motivation [78].

Another important fact or component of success and competitiveness of the company in the international market environment is the corporate culture, which is a set of opinions, value systems and behaviour standards unique for each organization and represents the specific character of its functions [79]. Corporate culture is primarily created in the minds of the founders themselves, and it seeks to summarize the vision, mission, strategy, and goals of the company and then illustrate their ideas and expectations within the functioning of the company in terms of relationships between people, their relationship to work, organization, and society. In addition, the corporate culture also serves as a tool for identifying customers with a given company and as a tool to assist the company’s employees themselves in dealing with potential adaptation and integration problems [20].

As it is written by [80,81,82,83,84], defining the corporate culture is very difficult, since, under the culture itself, everyone imagines something different. In general, the corporate culture is a set of fundamental and decisive ideas, values and standards of conduct that have proven to be effective in the past and are accepted and perceived by employees as universally valid. Employees are expected to respect and behave following these values and disseminate them through its tools. Authors such as [85,86,87] also agree with this statement, going to say that the given set of ideas, values and standards of behaviour that are shared and subconscious by members of the organization fundamentally defines not only the organization’s view of itself but also its view of its environment.

The role of business managers is then to create and maintain a strong and healthy corporate culture, which in turn acts as an effective motivator for the performance of the employees, while also significantly contributes to the effective management and development of people in the organization. Nevertheless, it is necessary to keep in mind the need to respect the individual national and cultural specifics and circumstances [20,88,89].

The basic definition of international companies/corporations states that “These are private or state-owned or jointly owned companies or units that are established in different countries of the world and are interconnected in such a way that one or more of them can create a significant influence on the activities of others, especially concerning the sharing of resources and knowledge” [90] (p. 12).

Several authors such as [26,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] emphasize that the degree of dependence of foreign subsidiaries on the parent company, as well as the type of strategy for creating an organizational culture play a significant role in the leadership of international companies. Based on the written international companies can be divided into:

- Ethnocentric—parent company has an excessively strong position and a decisive influence on almost all decisions of its subsidiaries. Companies believe that home-trained management with an intimate knowledge of technology, products, policies, corporate culture, and leadership style is more capable and trustworthy than any other management.

- Polycentric—individual subsidiaries operate independently of each other, their policy is greatly influenced by the cultural peculiarities of individual host countries and the universal goals, procedures and methods of the parent company “must” be respected only to a limited extent. The main advantage of the mentioned strategy is considered to be the knowledge of the home environment, language, customs, and ways of doing business, as well as stimulating creativity and developing new approaches to the solving of problems.

- Regiocentric—parent company combines its interests with the interests of subsidiaries on a regional basis. The strategy is used mainly in the countries of Central Europe and focuses on selection on a regional basis.

- Geocentric—uses specific features of individual national cultures to create a unified corporate culture, which then represents an integrated culture, but not as a result of cultural dominance, but as a purposeful and effective connection of all regional parts of international society. At the same time, the company strives for the overall optimization of business processes and conscious defense against the dominant influence of the parent company’s culture. Under the pressure of global processes, more and more multinational companies are striving to move to a geocentric model that allows the most optimal use of all input sources, overcomes the loss of interest in the ethnocentric model and duplication and redundancy in the polycentric model.

3. Materials and Methods

The nowadays market environment is principally characterized by the globalization, development of the market environment, intensifying competition, increasing concentration and internationalization, as well as increasing pressure on market players. The quality of managers in a network of companies with foreign capital participation, their ability to adapt to different cultures and environments, as well as their ability to properly address their subordinates come to the forefront [19,20,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110].

The aim of the paper is to point out the fact that leadership and motivation can be perceived as important aspects of the international company’s corporate culture.

The reason for choosing the given object of research was our professional interest in the given area, both in pedagogical and research level, as well as in the practice. We have been conducting research in this field since 2010. The authors of the submitted paper, work as the experts in the commission for the evaluation of the national projects of the Slovak Chamber of Agriculture and Food and at the same time as experts in the international project, “Assessing and Changing Adults’ Behavior on Sustainable Consumption of Food”. The personal meetings and interviews with managers of the companies revealed a gap that needed to be explored and this gap was connected with leadership and motivation as important aspects of the international company’s corporate culture. It allowed us to conduct the research presented in the submitted paper. The surveyed international company agreed with the publication of the results. We consider them as an interesting and suitable base to fulfil the above-mentioned gap in the academic field as well as in the practice. However, the company did not wish to use its name in the paper; therefore, it was redacted.

The paper focuses on both managers and selected groups of employees in terms of their ability to adapt to different cultural influences. In addition to the main aim, the subject matter required the selection of the object of investigation—an international Italian company and its subsidiaries situated in Germany (subsidiary 1), Turkey (subsidiary 2) in the Czech Republic (subsidiary 3), and Italy (subsidiary 4 and 5), as well as defining the subject of the investigation—leadership and motivation styles in the parent company and its subsidiaries and setting a total of eleven hypotheses, focused on the three research areas, namely, leadership, motivation and corporate culture.

- Hypotheses formulated in connection with the field of leadership:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There exists the dependence between the prevailing relationships in the company and the perception of the separation between superiors and subordinates.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There exists the dependence between the choice of a particular working option and the nationality of the respondents.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There exists the dependence between the applied leadership style and the nationality of the respondents.

- 2.

- Hypotheses formulated in connection with the field of motivation:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

There exists the dependence between individual significance rates of motivational factors and categories of respondents.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

There exists the dependence between the attributed significance rates of motivational factors and the level of education of individual respondents.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

There exists the dependence between the position of wages in the ranking of employees and their level of education.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

There exists the dependence between the position of wages in the ranking of employees and their job classification.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

There exists the dependence between the used forms of self-improvement and the perception of the relationship between improving work commitment, increasing professional qualifications and increasing the financial remuneration of employees.

- 3.

- Hypotheses formulated in connection with the field of corporate culture:

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

There exists the dependence between the preferred possibility of overcoming possible cultural differences and the category of respondents.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

There exists the dependence between the preferred possibility of overcoming possible cultural differences and the level of education of the respondents.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

There exists the dependence between the preferred possibility of overcoming possible cultural differences and the nationality of respondents.

When formulating the hypotheses, we relied on previous findings and knowledge from our research activities [19,20,111,112,113,114] as well as from the research of acknowledged authors in the given field, e.g., [14,15,16,17,18,21,22,23,115]. Employee commitment fosters the success of any organization [116]. Organizational leaders seek to cultivate the highest level of commitment among their employees. This commitment was influenced by how motivated employees are to perform their jobs satisfactorily. Ref. [116] observed that employee motivation is dependent on how satisfied employees are with the way their organizations operate. Employee motivation refers to how employees feel toward and perceive their organizations as well as how they are affected by leadership styles [116]. Therefore, developing a high level of commitment among employees means developing effective leadership skills on the part of the administrator. Implementation of leadership in an organization is pivotal for motivating employees and achieving their organizational commitment [117]. As several researchers have noted (e.g., [116,118,119]), knowledge gaps exist regarding how leadership affects employees’ development of motivation and also its connection to corporate culture.

As it is mentioned above, there is a gap in the research regarding the interconnection between leadership, motivation and the corporate culture and this is why we have tried to show, that leadership and motivation are important aspects of the corporate culture of an international company.

As the main research method, we used the method of the questionnaire survey, which was divided into two separate but logically connected questionnaires—the first one focused on the employees and the second one on the top management. The total number of questions in the questionnaire focused on employees was 26+ classification questions and in case of top management 28+ classification questions. Almost all of the questions (without the exception of one in both questionnaires) were formulated as closed, where the respondents could explain their opinion by their choice of one or more previously given answers, or by using a numerical scale, which has allowed them to organize their choices up to the perceived level of importance and significance (from 1 to 5, where 1 has meant the most significant and 5 the least significant).

All questions were focused on three basic areas, namely, the applied leadership style (e.g., questions about the prevalence relationships in the company, about the existence of conflicts, about the used conflict resolution options etc.), motivation (e.g., questions about the company’s interest in the motivation of its employees, about the motivation factors, about the importance of wage and other motivation factors in the respondents’ value ladder etc.), and corporate culture (e.g., questions about sharing the same social values and symbols in the whole company, about the existence of common traditions, rituals and legends, about the need to change the given corporate culture etc.).

To address foreign-language respondents, the questionnaire was translated into English and German language.

An unnamed international company based in Italy, including its subsidiaries both on its own and on the foreign market, was approached for research purposes.

The research aimed to obtain as much information as possible. A total of 270 questionnaires were sent by email and further disseminated in a personal form; thus it ensured a 100% return on the questionnaires. The mentioned number of sent questionnaires is representing the number of involved respondents and thus the total number of employees, including 10 top managers, 20 middle management employees and 240 operational management employees. Up to the mentioned, as well as up to Slovin’s Formula , where n = number of samples, N = Total population and e = Error tolerance (level) [120], the sample can be at 95% confidence level considered as representative as n ≥ 161.19. The percentage mistake of the estimate (, where E = percentage mistake of the estimate, z = 95% confidence level, N = sample size, π = 50% character ratio, n = number of respondents; and where the permissible interval is between 1 to 10% [121]) is equal to 0, as all employees were involved in the research.

The total numbers, as well as the representation of individual employees in specific enterprises, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the number of respondents (in absolute numbers).

The influence of culture on leadership and motivation of employees in international companies can be monitored with the help of experts. That is why the first part of this paper presents a theoretical introduction to the given issue. In this section, we have studied and analyzed selected sources of information by the heuristic method. Similarly, management and motivation as well as the corporate culture in the analyzed companies were assessed at the research stage.

Another part of the research consists of a questionnaire survey, its evaluation and subsequent interpretation of the results. In terms of the obtained data, the statistical data set represents the answers of the respondents from the sample, which consists of 270 respondents.

For the need of deeper and more extensive analysis of the obtained data, the results of verified dependencies were evaluated and interpreted in the statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics and the Excel add-on, XL Stat program using the following correlation coefficients and parametric tests: Pearson Chi-square Test, Fisher’s Exact Test, Cramer’s V coefficient, Kendall rank correlation coefficient, Eta coefficient, Spearman coefficient, and the following non-parametric tests: Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon W statistics, Friedman’s test, and Kruskal–Wallis test. As a decisive criterion for acceptance, respectively rejection of the null hypothesis, an alpha significance level of 5% was chosen. As the computed p-value was lower than the significance level alpha = 0.05, we have rejected the null hypothesis H0 and accepted the alternative hypothesis H1. The risk to reject the null hypothesis H0 while it is true was in all interpreted cases lower than 0.01%. In the case of finding the dependence, its strength was subsequently interpreted based on the following scale: correlation up to 0.1 is considered as trivial, correlation from 0.1 to 0.3 is considered as small, correlation from 0.3 to 0.5 is considered as medium, and the correlation above 0.5 is considered as large [122].

4. Results

As it was mentioned in the section Materials and Methods, in the questionnaire survey we have focused on three research areas, namely, leadership, motivation, and corporate culture. In addition to the above stated, due to the need for a better understanding of the given issue, its deeper and more extensive analysis, we chose the possibility of creating two questionnaire surveys, where we wanted to compare and interpret the answers of both managers and their subordinates.

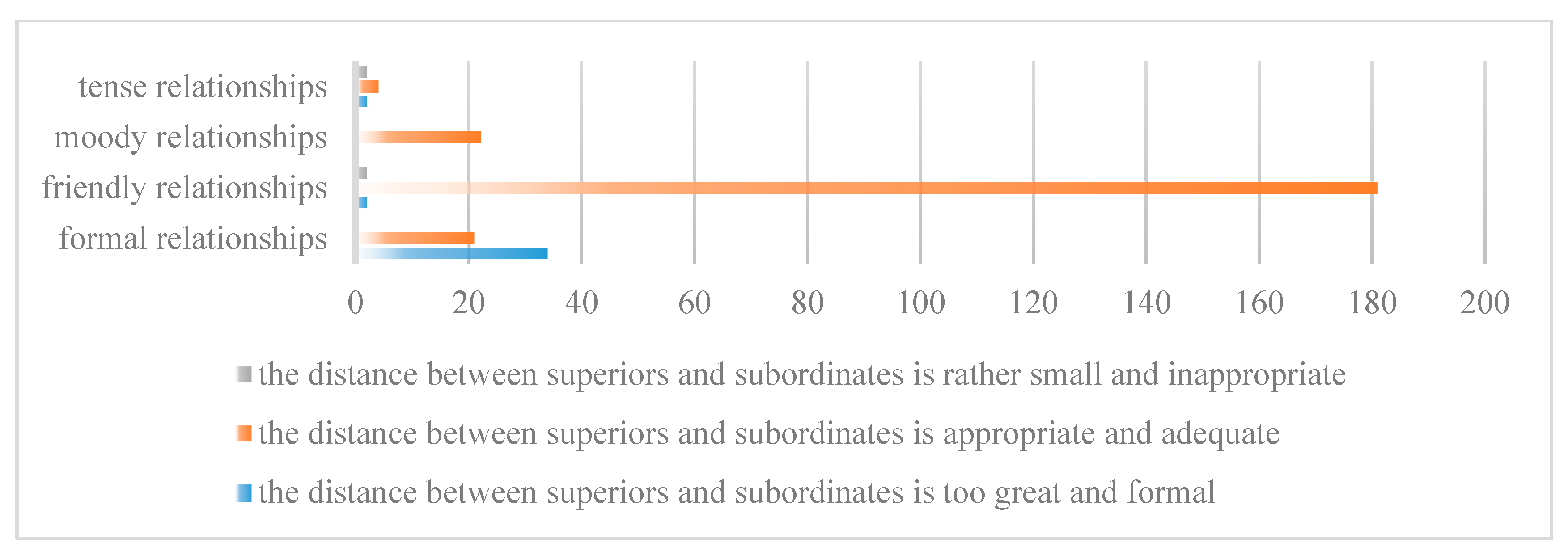

Based on the results of our analysis, it can be concluded that the mostly applied leadership style in the researched international company is the democratic one, which is characteristic with a participative role of employees in the decision-making process. The only exceptions from the mentioned are the subsidiaries 1 (based in Germany) and 5 (based in Italy), which apply an autocratic leadership style (known for individual control over all decisions and little input from group members). These findings are also confirmed by the respondents’ answers to other questions formulated in the questionnaire, e.g., the question of prevailing relationships in the given company, or the question of perceived distance between the superiors and subordinates; where the respondents from subsidiary 1 (based in Germany) and subsidiary 5 (based in Italy) stated that in their companies there are prevalent formal relationships, or that the distance between superiors and subordinates is too big and formal. In the context of evaluating the issues, the Hypotheses 1 was formulated and further tested by Pearson’s Chi-square Test, Cramer’s V Coefficient, and Phi coefficient. The results of the mentioned tests are presented in Table 2 (Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.000, Cramer’s V Coefficient was equal to 0.554 and Phi coefficient was equal to 0.784), from which it can be seen that there is a statistically significant and at the same time positive dependence between the tested variables and that the perception of separation between superiors and subordinates significantly affects the relationships in the enterprise. The mentioned is presented in Figure 1, from which it can be seen that those respondents who stated that the distance between superiors and subordinates is appropriate and adequate perceive the relationships in the workplace as friendly, while those who stated that the distance between superiors and subordinates is too great formal perceive the workplace relationships as formal.

Table 2.

Dependence between the prevailing relationships in the enterprise and the perception of separation between superiors and subordinates.

Figure 1.

Relationship between Prevailing Relationships in the Enterprise and Perception of Separation between Superiors and Subordinates (in absolute numbers); Source: Own Research.

Other questions regarding the applied leadership style include questions about prevailing situations where a problem has occurred, as well as the used options for the solution of potential problems. In this case, the respondents had to choose one of the given options, which best describes their current situation. Based on the results of our research, it can be stated, that in case of a subsidiary 1 (based in Germany), there is applied an authoritative better said autocratic leadership style—as the most common situations prevailing among co-workers when the problems arise are: insecurity, stress, fear, rivalry, commands, and regulations. In the situation when there arises a potential problem on the workplace, in most cases the respondents stated, that the manager chooses to consult with his subordinates (confirmed by more than 73% of respondents from the field of company’s management and 65% of respondents from the field of employees). Unfortunately, in the case of 40% of answers from the field of employees, there was indicated, that the manager pays attention to his employees only formally.

The suitability and the adequacy of the applied leadership styles are mainly evidenced by the responses of the respondents regarding the preferred working option, where respondents from subsidiary 1 (based in Germany) and subsidiary 5 (based in Italy) rather chose to work independently (66.67% of respondents from subsidiary 1) or to work under the direct supervision of a superior (51.52% of respondents from subsidiary 5), which is characteristic for the autocratic leadership style. Concerning this question, Hypothesis 2 was formulated and examined. Based on the results shown in Table 3 (Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.000, Cramer’s V Coefficient was equal to 0.319, and Phi coefficient was equal to 0.552), it can be stated there exists a statistically significant and at the same time medium dependence between the preferred working option and the nationality of respondents. The results of our research declare that while Czech respondents prefer to work in groups, German respondents prefer to work independently, Turkish respondents prefer to work under the direct supervision of their superior the Italian respondents prefer to work independently respectively to work under the direct supervision of their superior.

Table 3.

Dependence between the choice of particular working option and the nationality of the respondent.

Similarly, Hypothesis 3 was formulated and further examined by Pearson’s Chi-square Test, Cramer’s V Coefficient, and Phi coefficient. Based on the results shown in Table 4 (Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.03 and Cramer’s V Coefficient, as well as Phi coefficient, were equal to 0.724) we can conclude there exists a statistically significant and at the same time strong dependence between the tested variables, indicating that the nationality of managers has a statistically significant and strong effect on the choice of applied leadership style.

Table 4.

Dependence between the applied leadership style and the nationality of the respondents.

Even in the case of the second investigated area—namely, the area of motivation—it can be concluded that there were recorded many interesting findings which suggest that same as leadership, also motivation is an important attribute of corporate culture and is therefore justified to perceive and evaluate these areas together.

Based on the obtained information, as well as on the results of our survey it can be stated that although the management of individual companies think they are interested in a high level of motivation of their employees (confirmed by 60% of respondents in the field of top and middle management), or that they sufficiently familiarize their employees with the applied motivation systems (confirmed by 70% of respondents in the field of top and middle management), the employees feel some shortcomings and reserves (confirmed by almost 77% of respondents in the field of employees), and that they are only partially aware of the incentive schemes (confirmed by almost 29% of respondents in the field of employees). As we found out later, the differences were caused by the dissatisfaction of some employees, who thought that the best way to show their dissatisfaction is to mention the less flattering answers. Despite the fact that it can be said that the parent company itself, as well as its subsidiaries, are interested in a high level of motivation for their employees and are planning to correct their shortcomings over the time.

One of the tasks of a manager is to promote productivity among his employees, which requires motivation. To encourage them, managers must understand what motivates people [53]. For this reason, we have decided to examine the above-mentioned statement and formulated a similar question regarding the attributed measure of the significance of individual incentive factors both for the management of individual companies and for the employees. In this case, the respondents could organize their choices up to the perceived level of importance and significance—there was given a numeric scale from 1 to 5, where one has meant the most significant and five the least significant and the respondents could organize the given attributes up to their opinion and need. The results of the questionnaire survey offered some interesting findings—while in the case of employees is the wage the most important factor for of their motivation (evaluated as A), in the case of managers it’s not quite like that—the most important factors are the wage and social care (both evaluated as A) (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

Results of Friedman’s test—individual significance rates of motivational factors (employees).

Table 6.

Results of Friedman’s test—individual significance rates of motivational factors (managers).

Concerning the mentioned findings, the Hypothesis 4 was formulated and further tested by Pearson’s Chi-square Test supplemented by Eta coefficient, Kendall Tau b, Kendall Tau c, and Spearman’s coefficient, further with the use of non-parametric tests: Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon W statistics, which were evaluated in the program IBM SPSS Statistics and with the use of Kruskal–Wallis test, which was evaluated in the program XL Stat. Based on the obtained results, we can conclude that for motivational factors, such as “wages, wage, social care, work, working time, the possibility of exercising their abilities, possibility of career growth, the possibility of further education, possibility to engage in business goals, as well as the employees’ awareness of business events” is the attributed degree of significance largely influenced by the category of respondents. In other words, in the case of the mentioned motivating factors, their attributed degree of significance is different for employees and different for managers (Table 7).

Table 7.

Dependence between individual significance rates of motivational factors and categories of respondents.

Subsequently, Hypothesis 5 was formulated and examined by Pearson’s Chi-square Test, Eta coefficient, Kendall Tau b, Kendall Tau c, and Spearman’s coefficient, respectively Kruskal–Wallis test, which results are shown in Table 8. Based on the obtained results, it can be confirmed that when attributing the level of significance to the incentive factor of wage, there is a medium and direct dependence between the given variable and the level of education of the individual respondents and in the case of incentive factor the possibility for further education, there is a strong but indirect dependence. Regarding other motivational factors, in most cases, there is either a weak direct dependence or a weak indirect dependence among the tested variables. The only exceptions are motivational factors such as the atmosphere at the workplace, possibility to engage in business goals, and corporate image, where there cannot be observed any dependence, respectively there is only a very small and statistically insignificant dependence (Table 8).

Table 8.

Dependence between the attributed significance rates of motivational factors and the level of education of individual respondents.

Concerning the position of wages in the ranking of employees, the Hypotheses 6 was formulated and further examined by Pearson’s Chi-square Test supplemented by the results of Fisher’s exact test, Cramer’s V Coefficient, and Phi coefficient and the Hypothesis 7 was formulated and examined with the use of Pearson’s Chi-square Test, Cramer’s V Coefficient, and Phi coefficient. Based on the evaluation of both mentioned relations, it can be concluded that while there is no statistical dependence between the position of the wage in the value chart of employees and their level of education (Table 9—the Pearson’s Chi-square test value was equal to 0.678, which means that we cannot reject the null hypothesis), in case of the position of the wage in the value chart of employees and their job classification there is a statistically significant, but only weak, dependency that could only be the result of random sampling (Table 10—Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.01 and Cramer’s V Coefficient, as well as Phi coefficient were equal to 0.259).

Table 9.

Dependence between the position of wages in the ranking of employees and their level of education.

Table 10.

Dependence between the position of wages in the ranking of employees and their job classification.

Findings from the evaluation of questions regarding to the causal relationship between the improvement of work engagement, increasing the professional qualifications of the respondents and increasing their financial remuneration are similarly interesting as the results and findings presented so far. Regardless of the fact which category of respondents was examined—up to 93% of respondents believe that between improving their work commitment or increasing their professional qualifications and increasing their financial remuneration is a direct and causal relationship. This finding should indicate a higher willingness of employees to increase their professional qualifications, but this has been partially rebutted in the evaluation of the next question. Although individual managers of the surveyed companies support their employees in upgrading their professional qualifications, up to 34% of employees are not interested in this kind of support. However, this difference was caused by the fact that respondents with a completed apprenticeship or its equivalent, who held the positions of cleaning staff and workers did not consider this increase necessary. However, respondents with secondary education had a different opinion and therefore reported they use several of the supported but also unsupported forms of upgrading their qualifications.

Subsequently, we also examined Hypothesis 8 which was tested by Pearson’s Chi-square Test supplemented by the results of the Cramer’s V Coefficient and Phi coefficient. Based on our findings presented in Table 11, we can conclude that between the two tested variables there is no statistical dependence—the Pearson’s Chi-square test value was equal to 0.102, which means that we cannot reject the null hypothesis.

Table 11.

Dependence between the used forms of self-improvement and the perception of the relationship between improving work commitment and increasing professional qualifications and increasing the financial remuneration of employees.

The last examined area was the area of corporate culture, in which we have verified the statement of [123], that corporate culture is primarily about the everyday life of a company and especially about the behaviour of its managers and thus how they make decisions, resolve conflicts, communicate, reward and motivate (the respondents had again to choose one of the given options, which best describes their current situation). Our questionnaire survey confirms this statement, as the most frequent answers of the respondents to the question of the most important factor in terms of corporate culture formation were the behaviour of top management (37.41% of respondents), applied style of communication (28.15% of respondents), and motivation (27.04% of respondents).

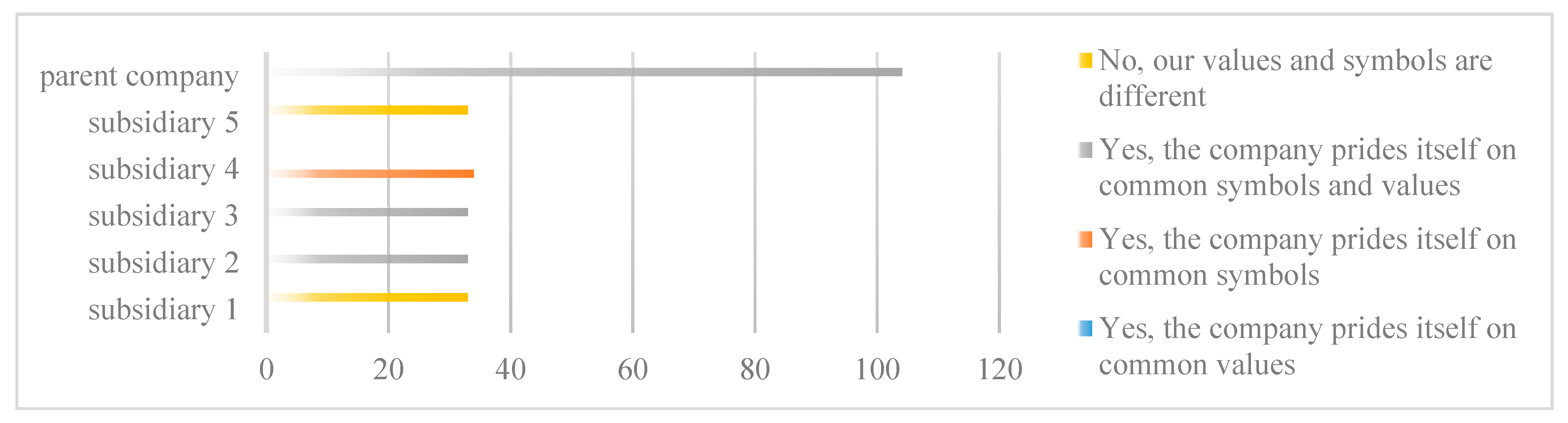

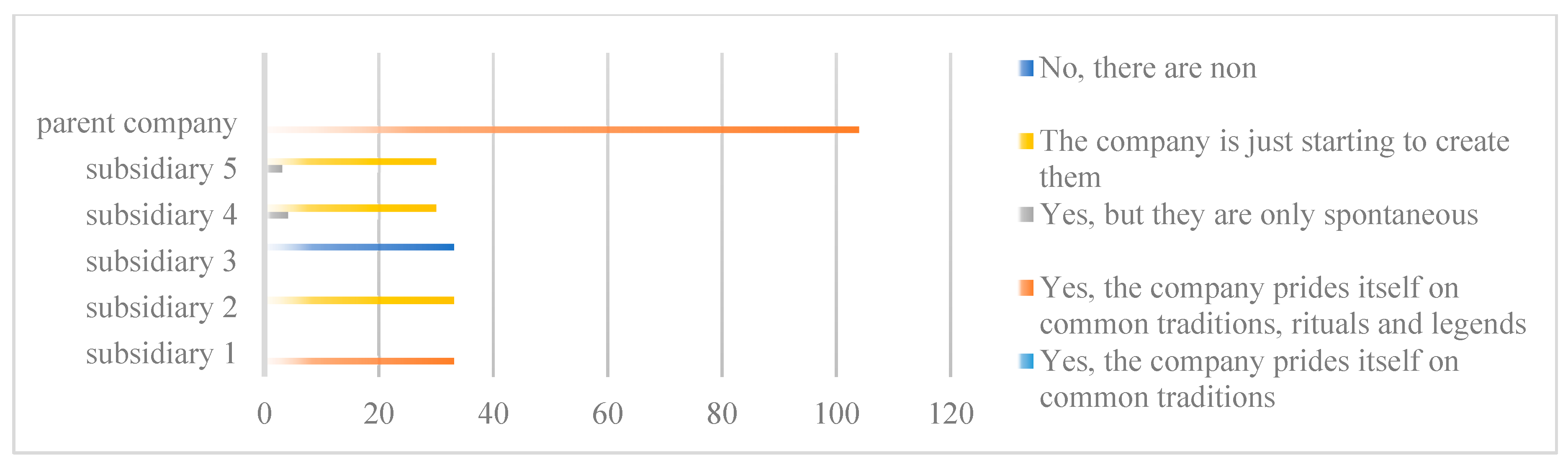

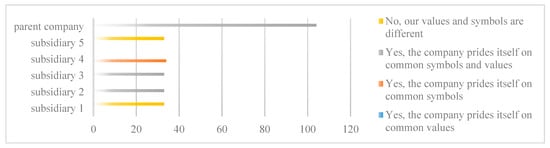

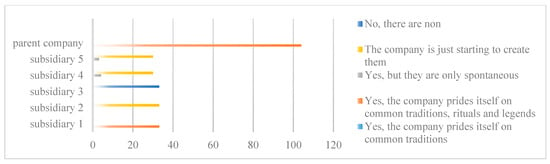

To determine the consistency of corporate culture throughout the whole surveyed company, in both questionnaires there were formulated the questions concerning the sharing of the same social values and symbols, as well as the common traditions, rituals, and legends. Based on our findings, it can be stated that the parent company does not respect the same symbols and values or common traditions, rituals, and legends, whereas while the parent company and its subsidiaries—subsidiary 2 (based in Turkey) and subsidiary 3 (based in the Czech Republic) use the same values and symbols, subsidiary 1 (based in Germany) uses only the same symbols and subsidiary 5 (based in Italy) as well as the subsidiary 4 (based in Italy) are based on different values and use different symbols, logos, and brands than their parent company and whereas the parent company adheres to common traditions, rituals, and legends, its subsidiaries are only beginning to shape them (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Sharing the Same Social Values and Symbols (in absolute numbers); Source: Own Research.

Figure 3.

Existence of Common Traditions, Rituals, or Legends (in absolute numbers); Source: Own Research.

Since our research has also sought to determine the degree of dependence of subsidiaries on their parent company as well as the level of enforcement of the original national culture of the parent company; the issue addressed to the corporate governance area of applied leadership styles has been also explored. Based on our findings and results of our research, we can conclude that the parent company is indeed not interested in forcibly promoting its national culture and prides itself on respecting the cultural and national specificities of individual countries.

As interesting findings in the field of corporate culture appear especially those arising from the evaluation of the questions related to the nature or mannerism of the corporate culture as well as the questions of its change, where we have found out that although 14.2% of respondents in the field of employees feel that their corporate culture is unnatural, and therefore they do not feel comfortable, only 4.6% think it needs to be changed, and only 20% of respondents from the top and middle management and 42.1% of respondents from the employees think it needs to be changed only in exceptional situations. This finding was later explained by the fact that the employees are accustomed to the used corporate culture and they are unwilling to changes or they are frightened of them.

Due to the internationality of our research—implementation of research in various cultural environments—it was necessary not only to develop multilingual questionnaires, but also to incorporate into them the questions related to the national plurality of employees of the researched company, conflict issues and the questions related to the problems arising from the cultural differences, as well as issues related to overcoming the possible cultural differences. The evaluation of the questions revealed, that even though the company employs people with different nationalities, the cultural differences of its employees rarely cause problems or they do not cause them at all. The only exception is the subsidiary 1 (based in Germany), whose executives stated that the cultural differences cause them quite frequent problems. The problems are mainly related to the fact that while German managers are primarily concerned with formality, punctuality and precision, Italian managers are more known for their flexibility, informality, and resistance to planning [124].

Concerning the issue of problems related to cultural differences, the question of overcoming the potential differences was also examined. This question was answered by only 127 respondents; it means only those respondents who have answered positively to the question regarding the cultural differences cause them problems. Of particular interest were the findings that while executives preferred the possibility of learning the language or the possibility of obtaining as much information as possible about the given culture, so the staff preferred to communicate with the given partner as often as possible. In connection with the evaluation of the given question, the Hypothesis 9, 10, and 11 were formulated and examined by Pearson’s Chi-square Test, Fisher’s exact test, Cramer’s V Coefficient, and Phi coefficient. Based on the results in Table 12, Table 13 and Table 14, it can be concluded that while there is a statistically significant and strong dependence between the variables tested in Hypothesis 9 (in the case of results evaluated in whole, the Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.000 and Cramer’s V Coefficient, as well as Phi coefficient, were equal to 0.563; Table 12), in the case of other two verifies hypotheses and their variables, there is only a medium but statistically significant dependence—in the case of Hypothesis 10, the Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.000, Cramer’s V Coefficient was equal to 0.338, and the Phi coefficient was equal to 0.478 (Table 13) and in the case of Hypothesis 11 the Pearson’s Chi-square test value was 0.000, Cramer’s V Coefficient was equal to 0.440, and the Phi coefficient was equal to 0.879 (Table 14).

Table 12.

Dependence between the preferred possibility of overcoming possible cultural differences and the category of respondents.

Table 13.

Dependence between the preferred possibility of overcoming possible cultural differences and the level of education of the respondents.

Table 14.

Dependence between the preferred possibility of overcoming possible cultural differences and the nationality of respondents.

5. Discussion

Despite the fact that the issue of corporate culture has been investigated from different point of views, e.g., by [115], who aimed at investigating the role of certain factors, namely—interpersonal trust, communication between staff, information systems, rewards and organization structure, and in organizational culture in the success of knowledge sharing; by [18], who has investigated 140 respondents and who’s results have shown that if the transactional leadership and organizational culture are supported by high work motivation, a company will be able to improve performance action; respectively; by [125], who has examined 118 respondents and has tried to show and highlight the interconnection between the motivation, job satisfaction, and corporate culture, and whose results show that there really exists the relationship between employee motivation and job satisfaction, corporate culture and job satisfaction, and corporate culture and employee motivation; the issue of leadership and motivation as aspects of the corporate culture of an international company are still shrouded in mystery and unknown. The present paper addresses a gap in the literature and research in the given field and it brings a new highlight to it.

Our results show that the leadership and motivation can be perceived as important aspects of the international company’s corporate culture and their principles can be applied with the respect to cultural differences between individual subsidiaries and nationalities. The mentioned is proved by the fact that while the parent company and most of its subsidiaries are applying the democratic leadership style, which is characterized mainly by two-way communication between the individual participants, rewards and a more relaxed atmosphere at the workplace, which can also lead to better motivation of employees (proven, e.g., by [19,21,29,126,127], etc.); there are also some subsidiaries which apply the autocratic leadership style, characterized in particular by one-way communication, orders and regulations, and a greater distance between workers, which can lead to conflicts in the workplace (proven by the results of researches as [128,129,130,131]); the company as such can function properly and withstand a competitive environment.

Employee motivation is an innate force shaped and maintained by a set of highly individualistic factors that may change from time to time, depending on the particular needs and motives of an employee [124]. Despite the fact that each employee has a different level of motivation according to his system values [18] there exists one common claim that the most effective motivational factor is the wage, or praise as it was proven by the researches of [132,133,134,135,136] and also partially by our research—the mentioned statement was proven only in the case of respondents from the group work and the given was also confirmed by the results of Pearson’s Chi-square Test supplemented by Eta coefficient, Kendall Tau b, Kendall Tau c, and Spearman’s coefficient, as well as with the use of non-parametric tests: Mann–Whitney U test, Wilcoxon W statistics, Kruskal–Wallis test, and Friedman’s test, where there was shown that there exists a statistically significant relationship between the appreciated significance level of individual motivational factors and the category of respondents.

The last examined area was the area of corporate culture, in which we have confirmed the statement of [123] that corporate culture is primarily about the everyday life of a company and especially about the behaviour of its managers and thus how they make decisions, resolve conflicts, communicate, reward and motivate. The mentioned was also confirmed by the researches done by, e.g., [137,138,139] up to which we can say that the task for the right manager should not be only the leadership or effective motivation, but also the creation and maintenance of a pleasant and friendly working atmosphere, thereby removing barriers between workers, increasing the degree of belonging and loyalty to the company in which they work. A good corporate culture is then the basis of the proper functioning of the company, its future successes and economic results, but also an instrument of its competitiveness.

6. Conclusions

Based on the findings presented above, it can be clearly stated that in the examined company, the democratic leadership style is not applied to the extent as it was expected. While most subsidiaries and, of course, the parent company use the given leadership style, companies, or better said subsidiaries, exactly subsidiary 1 and 5, use its exact opposite, namely, the autocratic leadership style, characterized by unilateral communication in the form of orders and regulations.

Up to the questions of the impact of national specificities on the choice of used leadership styles and motivations, as well as the possibility of independent decision-making in the selection of the specific motivation method, it can be concluded that the individual leadership and motivation styles are indeed different depending on the national specificities of each country and that their choice is left to the managers of the companies themselves—the parent company has minimal involvement in the decision-making process in the case of subsidiary 2 (based in Turkey), subsidiary 3 (based in the Czech Republic), and subsidiary 1 (based in Germany), which are financially dependent on the parent company, and which at first consult the proposed ways of motivating their employees with the parent company and just then implement them in practice.

While the parent company favors a polycentric organizational structure based on the respect for and use of the national and cultural specificities of each country, its subsidiaries favor a different organizational structure—whereas the parent company, like its subsidiary 3 (based in the Czech Republic), applies a polycentric approach characterized by the respect for and use of the national and cultural specificities of each country, its subsidiary 2 (based in Turkey) and subsidiary 4 (based in Italy) use the regional-centric approach and subsidiary 5 (based in Italy) and subsidiary 1 (based in Germany) an ethnocentric approach. Based on what we found out in our research, it can be stated that the parent company is not interested in promoting and forcibly implementing the original national culture but is based on the respect for and use of the cultural differences of individual countries.

Recommendations and suggestions for practice:

- to adapt the leadership styles to the specific situations in which the companies are, or to try to find out what styles and forms of leadership are the best and most suitable for them. While a democratic and in some cases the laissez-faire leadership styles are considered to be the most appropriate and most satisfactory for the day-to-day running of a business, when the company is in “good” numbers, an autocratic leadership style seems to be the best one to overcome the problems caused by the economic crisis, or in situations where the business is in decline and threatened with going out of business

- to create a pleasant and friendly working environment that leads to higher motivation of workers. If the company manager shows interest in reducing the distance between him and his subordinates or in resolving the internal conflicts and increasing the involvement of workers in the problem-solving process, this act can be perceived by the employees as an indication that the manager cares about them, their opinion and he is trying to create a pleasant, supportive, and stimulating work place.

- focus on also on employee benefits, which can significantly increase employee motivation and thus contribute to their higher loyalty and belonging, because a properly and appropriately motivated worker is also a happy worker who likes to go to work, likes his work and does not look for other ways to make a living.

- if it is possible, to increase the motivation not only of the employees but also of their managers while emphasizing not just the financial stimulation of the employees but also their motivation in the form of praises, statements of the employee of the month, working rotation, last but not least by expanding and increasing their competence and involvement in “companies’ life”, respectively by expanding the work tasks especially to those employees, who do a monotonous work.

- the security, people’s underlying needs, personal growth as well as the sociability aspects are fundamental not just for people, but they are also the essential aspects of an effective organization, which cannot be neglected. This is why the management has to think about them, incorporate them into the company’s motivation system, and up to that, as it is also written by [140], it has to evaluate the employee suggestion scheme and use the feedback from the workforce to improve the organizational environment and satisfy their needs and skills.

- to continue to support their employees in their further qualification growth and to organize training and courses for them not only on the operation of new machines and equipment but also on their language training for possible work abroad.

- to raise employees’ awareness of the corporate culture of their own companies and to organize more joint events and informal meetings to strengthen the workplace relationships and create a more comfortable and friendly working environment that improves the communication, enhances creativity and motivation of employees, helps to achieve the business goals, and of course, it helps managers can increase their effectiveness by getting a better grasp on the real needs and desires of the employees.

- to place a greater emphasis on creating and consolidating common traditions and rituals not only in the area of leadership or motivation, but also in the field of social life and organization life. Common traditions or rituals contribute to a sense of belonging, making it easier for a worker to identify with his company and become more loyal.

The limits of the submitted paper are mostly the facts that the research was carried out in only one international company and its subsidiaries situated in different countries of EU, and therefore it cannot be assumed that the results are valid for the whole industry. Furthermore, we have focused just on one industry in a few countries, which opens up an opportunity to conduct research in other industries and more countries worldwide (even outside the EU). We also realize the fact that leadership, motivation and also the corporate culture is evolving, and the situation described in the submitted paper may change in the future.

Despite the above mentioned and the fact that not all of our results are statistically significant—not all tested hypothesis were confirmed (two of formulated hypothesis have been rejected), we still think that the submitted paper offers the results of a unique research which present the base for the similar research and practical application in the other companies and countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; methodology, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; software, I.K.; validation, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; formal analysis, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; investigation, I.K., Z.K. and P.Š.; resources, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; data curation, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; writing—review and editing, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; visualization, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; supervision, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š.; project administration, I.K. and Z.K.; funding acquisition, I.K., Z.K., and P.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fuchs, D.A.; Lorek, S. Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of Promises and Failures. J. Consum. Policy 2005, 28, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.; Zuiker, V.S.; Danes, S.M.; Stafford, K.; Heck, R.K.Z.; Duncan, K.A. The impact of the family and business on family business sustainability. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 639–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Mena, J.A.; Gonzalez-Padron, T. The Structure of Sustainability Research in Marketing, 1958–2008: A Basis for Future Research Opportunities. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 39, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, K. Sustainability and performance. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Szekely, F.; Knirsch, M. Responsible leadership and corporate social responsibility: Metrics for sustainable performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 628–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Shang, J. How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.; Langella, I.; Carbo, J. From green to sustainability: Information technology and integrated sustainability framework. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Smith, J.S.; Gleim, M.R. Green marketing strategies: An examination of stakeholders and the opportunities they present. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W.; Courtice, P. Sustainability Leadership: Linking Theory and Practice. SSRN Electron. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.M.G. Research on Public Service Motivation and Leadership: A Bibliometric Study. Int. J. Public Adm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Lorincová, S.; Ližbetinová, L.; Pajtinková Bartáková, G.; Merková, M. Cluster Analysis Used as the Strategic Advantage of Human Resource Management in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises in the Wood-Processing Industry. BioResources 2017, 12, 7884–7897. [Google Scholar]

- Hitka, M.; Závadská, Z.; Jelačić, D.; Balážová, Ž. Qualitative Indicators of Company Employee Satisfaction and Their Development in a Particular Period of Time. Drv. Ind. 2015, 66, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachová, K.; Stacho, Z.; Bartáková, G. Influencing organizational culture by means of employee remuneration. Verslas Teor. Prakt. 2015, 16, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gagné, M. A Chinese-Canadian Cross-Cultural Investigation of Transformational Leadership, Autonomous Motivation, and Collectivistic Value. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; House, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The Motivational Effects of Charismatic Leadership: A Self-Concept Based Theory. Organ. Sci. 1993, 4, 513–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.M.; Hamid, K.B.A. Transactional Leadership and Job Performance: An Empirical Investigation. J. Manag. Bus. 2015, 2, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinova, A.; Naydenova, P. The Motivation Management Mechanism through the Prism of the Corporate Culture and the Corporate Social Capital. In Proceedings of the Economics and Social Development, 7th International Scientific Conference, New York, NY, USA, 24 October 2014; pp. 617–624. Available online: https://bib.irb.hr/datoteka/798645.CINGULA_Book_of_Proceedings_esd_NYC_2014_Published_str_334.pdf#page=624 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Wahyuni, N.P.D.; Purwandari, D.A.; Rahmat Syah, T.Y. Transactional Leadership, Motivation and Employee Performance. J. Multidiscip. Acad. 2019, 3, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sedliaková, I. Štýly Vedenia a Motivácie Ako Súčasť Firemnej Kultúry v Medzinárodnej Spoločnosti. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Management FEM SUA, Nitra, Slovakia, 2013; 306p. (In Slovak). [Google Scholar]

- Košičiarová, I. Vedenie a Motivácia Ako Atribúty Podnikovej Kultúry Medzinárodnej Spoločnosti, 1st ed.; Verbum: Neratovice, Czech Republic, 2019; 168p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Sedlák, M. Manažment; Iura Edition: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2009; 434p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Dudinská, E.; Jarab, J.; Budaj, P.; Špánik, M. Manažment Ludských Zdrojov, 1st ed.; Vydavateľstvo Michala Vaška: Prešov, Slovakia, 2011; 216p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Wasiluk, A. Waiting for a Leader. In Humanization of Work and Modern Tendencies in Management; Wydawnictvo Politechniki Czestochowskiej: Czestochowa, Poland, 2010; 201p. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, M.; Stephens, T. Management a Leadership; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2008; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.C. 21 Zákonov Vodcovstva; Slovo Života International: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2007; 284p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Dvořáková, Z. Management Lidských Zdroju; C. H. Beck: Praha, Czech Republic, 2007; 485p. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Birch, P. Leadership; Computer Press: Praha, Czech Republic, 2005; 95p. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Roóz, J. A Menedzsment Alapjai; PERFEKT: Budapest, Hungary, 2006; 352p. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Majtán, M. Manažment; SPRINT: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2007; 429p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Armstrrong, M. Armstrong’s Handbook of Management and Leadership, 2nd ed.; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2009; 256p. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, M.W., Jr.; Lombardo, M.M. Off the Track: Why and How Successful Executives Get Derailed; Centre for Creative Leadership: Greenboro, NC, USA, 1983; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum, R.; Schmidt, W.H. How to Choose a Leadership Pattern. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1973. Available online: https://hbr.org/1973/05/how-to-choose-a-leadership-pattern (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Blanchard, K.H.; Zigarmi, D.; Zigarmi, P. Leadership and the One Minute Manager: Increasing Effectiveness through Situational Leadership; William Morrow & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1999; 111p. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, V.H.; Yetton, P.W. Leadership and Decision-Making; University of Pittsburg Press: Pittsburg, CA, USA, 1973; 248p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.E. Leadership; General Learning Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, M.K. The Leadership Mystique: Leading Behavior in the Human Enterprise; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2006; 304p. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K.; Lippit, R.; White, R.K. Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates. J. Soc. Psychol. 1939, 10, 271–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likert, R. The Human Organization: Its Management and Value; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1967; 158p. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, R.R.; Mouton, J.S. Group Dynamics—Key to Decision Making; Gulf Publishing Co.: Houston, TX, USA, 1961; 305p. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectation; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; 255p. [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, J. Leadership; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978; 530p. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardin, H.; Russel, J. Human Resource Management; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; 722p. [Google Scholar]

- Boye Kuranchie-Mensah, E.; Amponsah-Tawiah, K. Employee motivation and work performance: A comparative study of mining companies in Ghana. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 9, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, A.S.; Schmitt, W.H. How to choose a leadership pattern. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1958, 36, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, F.E. A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness; The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1967; 310p. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey, P.; Blanchard, K.H. Management of Organizational Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1969; 147p. [Google Scholar]

- Mavhungu, D.; Bussin, M.H.R. The Mediation Role of Motivation between Leadershipand Public Sector Performance. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. Leadership Success and Organisational Vision; Mittalbux: New Delhi, India, 2005; 676p. [Google Scholar]

- Zhiyong, H.; Qun, W.; Xiang, Y. How Responsible Leadership Motivates Employees to Engage in Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment: A Double-Mediation Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Patzer, M.; Scherer, A.G. Responsible Leadership in Global Business: A New Approach to Leadership and Its Multi-Level Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, P. Jak Motivovat Lidi; Computer Press: Brno, Czech Republic, 2003; 117p. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter, S. Self-efficacy and organizational change leadership. Adm. Soc. Work 1998, 22, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.A. Motivation and Leadership in Social Work Management: A Review of Theories and Related Studies. Adm. Soc. Work 2009, 33, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; McClomb, G.E. Top Executive Leadership and Organizational Innovation. Adm. Soc. Work 1998, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Lipoldová, M.; Schmidtová, J. Employees’ motivation preferences in forest and wood-processing enterprises. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen 2020, 62, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.P.; Coulter, M. Management, 7th ed.; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2004; 600p. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. What Makes a Leader? Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; 210p. [Google Scholar]

- Alexy, J. Manažment Ludských Zdrojov; Iris: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2004; 257p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1954; 411p. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer, C.P. Existence, Relatedness and Growth: Human Needs in Organizational Settings; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1972; 178p. [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, F.; Mausner, B.; Snyderman, B. The Motivation to Work; J. Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959; 159p. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, D. The Achieving Society; Van Nostrand, Co.: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1961; 512p. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.S. Toward An Understanding of Inequality. J. Abnorm. Norm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 67, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroom, V. Work and Motivation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964; 331p. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B.F. Contingency Managemennt in the Classroom; New York Education: New York, NY, USA, 1969; 120p. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, G.P.; Locke, E.A. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; 413p. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A.; Shin, J. Work motivation: Directing, energizing, and maintaining effort (and research). In Oxford Handbook of Motivation; Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 505–519. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. A theory of goal-setting and task performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 212–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Work Redesign; Reading; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; 330p. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. How job characteristics theory happened. In Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development; Smith, K., Hitt, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Stamov Roßnagel, C. Leadership and Motivation. In Leadership Today; Marques, J., Dhiman, S., Eds.; Springer Texts in Business and Economics: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 2017–2228. [Google Scholar]

- Alghazo, A.M.; Meshal, A.-A. The Impact of Leadership Style on Employee’s Motivation. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2016, 2, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Asrar-ul-Haq, M.; Kuchinke, K.P. Impact of leadership styles on employees’ attitude towards their leader and performance: Empirical evidence from Pakistani banks. Future Bus. J. 2016, 2, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczmaraski, S.; Kuczmarski, T. Values-Based Leadership Rebuilding Employee Commitment Performance, and Productivity, Englewood Cliffs; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995; 256p. [Google Scholar]

- Broder, M.S. Motivation in the Workplace for Optimal Results Is Not a ‘One Size Fits All’ Implementation. 2015. Available online: http://wwwhuffingtonpost.com/michael-s-broder-phd/employee-motivation-productivity-_b_2615208.html (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Višňovský, J. Manažment Ludských Zdrojov, 2nd ed.; SPU: Nitra, Slovakia, 2003; 170p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Plamínek, J. Tajemství Motivace; Grada Publishing: Praha, Czech Republic, 2010; 127p. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Hitka, M.; Vetráková, M.; Balážová, Ž.; Danihelová, Z. Corporate Culture as a Tool for Competitiveness Improvement. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Turner, C. International Business. Themes and Issues in the Modern Global Economy, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010; 496p. [Google Scholar]

- Schabracq, M.J. Changing Organizational Culture: The Change Agent’s Guidebook; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2007; 262p. [Google Scholar]

- Zorkóciová, O. Corporate Identity II, 2nd ed.; Ekonóm: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2007; 282p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D. Improving Safety Culture: A practical Guide; J. Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2001; 259p. [Google Scholar]

- Poór, J.; Farkas, F. Nemzetkozi menedzement; KJK—KERSZOV: Budapest, Hungary, 2001; 434p. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Gažová Adámková, H. Organizačné Správanie v Podniku; Ekonóm: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2010; 226p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Antalová, M. Ludské Zdroje a Personálny Manažment; Ekonóm: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011; 162p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Teoretické zázemí konceptu organizační kultury. In Kultura Organizace a Supervize ve Vzájemném Pusobení, 1st ed.; Fakulta Humanitních Studií Univerzity Karlovy v Praze: Praha, Czech Republic, 2011; 102p. (In Czech) [Google Scholar]

- Ubrežiová, I.; Horská, E.; Mižičková, L.; Štrach, P.; Wach, K.M. Medzinárodný Manažment a Podnikanie, 1st ed.; SUA: Nitra, Slovakia, 2005; 125p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]

- Ubrežiová, I.; Košičiarová, I.; Ubrežiová, A. Medzinárodný Manažment a Podnikanie, 1st ed.; SUA: Nitra, Slovakia, 2013; 189p. (In Slovak) [Google Scholar]