Abstract

Recent years have witnessed a notable increase in the implementation of social innovation strategies for creating products with major social impact. Despite the lack of conceptual clarity still surrounding the term, social innovation, as a participatory research method, is finding scope for growth in agricultural cooperatives, whether in the areas of R&D and knowledge transfer, or in the commercialization of innovative products. Society has underscored the need for change in the environment and the implementation of new projects that help improve socioeconomic living conditions, promoting territorial development through social transformation. In the case of cooperativism in the olive oil industry in southern Spain, cooperatives are responsible for 70% of the oil produced there. As such, the actions carried out under their influence have a huge impact on the population and serve as tools that anchor people to their municipalities. This article analyses a case study from an olive oil cooperative, exploring the development of a social innovation project involving knowledge transfer and public awareness-raising through the label of an early harvest olive oil called “Primer Día de Cosecha” (First Day of Harvest). It also assesses the impact of the project on the population of the Andalusian municipality of Bailén (Jaén).

1. Introduction

For decades, rural areas in Spain have been a key experimental laboratory for social innovation. Initiatives include value propositions focused on the digital inclusion of citizens and the use of technology to boost people’s employability and quality of life, as can be seen in the recent study by the association Somos Digital [1]. However, there is still a lack of interaction between agents when it comes to developing strategic innovations in productive activities that ensure the competitive advantages offered by rural areas meet the new demands of the markets.

Such innovation processes have often been termed “slow innovation” [2]; they are local initiatives developed in response to the challenges of restructuring traditional industries in the primary sector and agri-food industry in peripheral and central regions during the 1980s. In fact, given their particular features and the importance of the involvement of local populations and municipal governments in stimulating the process of territorial development, innovations in rural areas have primarily been related to concepts such as open innovation [3].

According to Mozas Moral [4], companies and organizations from the social economy, such as cooperatives, are drivers of social development and structural change in municipalities; in the case of the olive oil industry, cooperatives account for 70% of the total (out of every 100 companies, 70 are cooperatives). Some international bodies such as the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy (UNTFSSE), Social Economy Europe (SEE), Cooperatives Europe and the International Cooperative Alliance have highlighted the fact that this industry is primarily composed of social economy companies, particularly cooperatives, which account for more than 75% of total production.

Bearing in mind the importance of these companies in olive oil producing areas, cooperatives have long been responding, to a greater or lesser extent, to the new challenges arising in relation to social innovation [5]. In this regard, we can find examples of different strategies that have emerged, either in the search for techniques or solutions aimed at lowering costs and promoting the sale of crops, or in the incorporation of diversification processes [6]. In order to rise to the challenges of globalization, cooperatives must meet the requirements of international competition. Given their profound influence on rural life and the rural economy, all initiatives focused on social innovation and the development of olive oil producing areas could be a key element in social cohesion and rural development. The involvement of cooperative enterprises in olive oil producing areas is therefore critical.

Much has been written about olive oil cooperatives in relation to their ability to stimulate rural development [7,8,9], but to the best of our knowledge, there is a gap in the literature when it comes to the influence of social innovation processes and instruments on this type of cooperative and on their rural environment. According to Sánchez-Martínez et al. [5], there are enough examples of social innovation to promote the renewal and improvement of the cooperative movement in response to the challenges posed by globalization, particularly competition from new producers around the world based on capitalist economic models without specific territorial ties. The research objective of this article is to analyse a case study involving the implementation of social innovation strategies in the area of cooperatives. To that end, we present the materials and methods used for the research, detail the results obtained from the case under analysis, and end by setting out the conclusions drawn from the research.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Social Innovation in the Context of Cooperativism in Olive Oil

The main role that the cooperatives play in fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) has been recognised in the institutional context by both the United Nations Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy and the International Cooperative Alliance’s Cooperatives Europe [10,11]. There is also extensive economic literature that demonstrates the alignment of cooperatives with SDG. These are business organisations whose management is designed to benefit all stakeholders, boosting economic development in their business areas [12].

Global olive oil production is registering continuous growth, linked not only to a steady expansion in the area dedicated to olive cultivation but also to an increase in the irrigated area and the introduction of technological improvements [13]. According to data from the International Olive Council [14,15], if we compare the 1990/91 season (when 1,453,000 tonnes of olive oil were produced) with the 2018/19 season (when 3,131,000 tonnes were produced worldwide), we can see that production has doubled, and forecasts indicate continuing growth. Looking at the countries responsible for this increase, while the cultivation of olive trees for oil production has traditionally been concentrated in the countries of the Mediterranean basin, there are more and more territories that, despite not having traditional olive groves, are responsible for a growing share of production [16].

As can be inferred from the figures cited above, in the domestic market, the supply greatly exceeds the demand. This translates into a substantial surplus, which creates many problems at the national and international level [16]. As a result, companies have to innovate and offer new alternatives for the commercialization of olive oils that promote ongoing territorial development.

In Spain, there are many undifferentiated private brands on sale. Almost 70% of all olive oil in Spain is sold under a store brand [17]; thus, with few exceptions, producing companies’ private labels do not have much of an impact. In view of this situation, there is a need to introduce innovative strategies that bring a differential added value to both the production and commercialization of olive oils. One such strategy may be social innovation.

While there have been numerous attempts to define it [18,19,20,21,22,23], there is still no consensus in the scientific community as to the definition of the term “social innovation”. BEPA’s [18] attempt at defining social innovation views it through the prism of three perspectives: (1) social demand, (2) the socioeconomic challenge for society as a whole, and (3) systemic changes in the direction of a more participatory society.

In the study on the meaning of social innovation by Hernández-Ascanio et al. [24], the authors argue that there is ambiguity in the efforts to establish a definition, despite the various attempts made to systematize the concept. They suggest that the “content of social innovation” can help to shed light on the matter through its different conceptual dimensions. These dimensions may variously include the objective of meeting social needs, identifying society’s demands, and establishing processes of social transformation [24].

In his recent review on social innovation as a participatory research method, Hernández-Ascanio [25] addresses the collaborative nature of social innovation from a research-action perspective. This type of practice—which Thiollent [26] describes as empirically-based social research designed and implemented so as to be closely associated with an action or the solution to a collective problem, and with the cooperative or participatory involvement of researchers and participants representative of the situation or the problem—places the capacity for social transformation at the very core of social innovation.

Social innovation thus constitutes a tool that enhances the development of a territory through the relationships between the individuals who share it [27], while also opening up new channels of communication between organizations and their surroundings [28]. Furthermore, it is a source of systemic organizational and cultural changes, which influence both general attitudes and values as well as organizational processes, structures, strategies and policies as well as methodologies, processes and links between the actors involved [29].

The Oslo Manual drawn up by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [30] includes references to innovation viewed from an economic perspective as a means of increasing the productivity and competitiveness of a company and helping reduce production costs as well as opening up new markets. In this regard, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), as a tool for fostering social innovation, forms part of current societal demands for businesses to give back to their surroundings some of the benefits they obtain through their business activity [31].

The social mission of social entrepreneurs is not to meet already existing demands but rather to meet new needs or offer new ways of responding to social demands, thus acting as agents of change [32,33]. As an entrepreneurial ecosystem of a social nature, cooperatives take on the role of institutional entrepreneurs [34], spearheading collective action in support of rural economic development. Moreover, at the local level these companies are a central pillar of the development potential of rural areas [35]. For regions that are highly specialized as producing areas, as is the case with olive oil in various parts of Andalusia, authors such as Sánchez-Martínez et al. [5] state that cooperatives act as organizations that not only drive the economic performance of the municipalities where they are located, but are also instruments of social cohesion [36]. Therefore, the actions undertaken by cooperatives are collective goods in the sense that they benefit rural society as a whole due to their multiplier effect on farmers and other local activities.

2.2. Context and Case Study

Olive oil production in Andalusia, a region in southern Spain, represents a significant share of total global production. Olive oil producing cooperatives are considered a driver of change and territorial development, particularly development in rural areas; indeed, this type of social economy company tends to be the most important business structure in Andalusian municipalities [37].

The beginning of the twentieth century saw the emergence of the first cooperative business models developed around olive oil. In the case study in question, in the municipality of Bailén (Jaén), two olive oil cooperatives were established. In 2009, these cooperatives merged into a single cooperative intended as a predominantly social entity committed to agribusiness and high tech. The result of said merger was the cooperative Picualia, a powerful, modern oil mill particularly renowned for the olive variety it uses, namely, Picual.

The merger process planted the seed for the social innovation projects that have been emerging in recent years. The current mill is located in one of the foremost olive oil producing regions in the world, and it is one of the most recognized companies worldwide in the production and commercialization of homegrown olive oils. Indeed, it has won major awards, such as the title of 2016 Best Olive Oil Mill in Spain granted by the Spanish Association of Olive Municipalities (AEMO). To date, this cooperative company has won more than 50 national and international awards.

According to the case studies and the contextualization of the cooperative sector presented by Sánchez-Martínez et al. [5], the Picualia agricultural cooperative sets an example as an innovation model, especially in terms of the methods created for remunerating those partners who strive to achieve a higher quality product. Among the most noteworthy measures are the different levels of payment to producers according to the type of olive harvest, with higher payments when the olives are picked directly from the tree than when they are collected off the ground. More recently, an exhaustive classification has been used to reflect the differences in the product delivered by each of the harvesters. The classification relies on an overall quality index, which enables the launch of projects such as First Day of Harvest.

3. Methodology

This study is aimed at analysing the impact of implementing social innovation strategies in the commercialization of a specific olive oil product; namely, early harvest extra virgin olive oil (EVOO). To that end, a cooperative located in one of the world’s main olive oil producing areas is taken as a case study. The cooperative in question is located in Bailén (Jaén). For the last five years, it has opted for the early harvest system and has marketed the EVOO First Day of Harvest.

The methodology thus centres around a case study, examined from a perspective that allows us to evaluate the added value with respect to the marketing, recognition, design and artistic value. In so doing, we can assess the impact of early harvesting as a social innovation formula applied to the cooperative olive oil production industry.

Data Collection and Analysis

Regarding the data collection for the analysis of the case study, we have reviewed recent studies that use methods based on the OECD’s REEIS criteria (relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability) for evaluating development programmes [35,36,37,38]. Thus, this article is grounded in the application of a holistic perspective to the study of a specific case, involving the interpretation of all the different factors that interact in a project of this type. As such, we opt for the use of a qualitative method.

First, in the Table 1 below, we describe the different actors involved in the production of the early harvest olive oil called “First Day of Harvest”.

Table 1.

Actors involved.

It should be noted that the incorporation of elements of design and artistic expression on the product label, as well as elements relating to communication and scientific research, is a differentiating factor contributing added value. It represents the outcome of an eminently personal artistic inquiry, with social innovation used as a tool to spark reflective, creative and interpretative artistic processes [39]. Moreover, it makes innovative use of retail sales of early harvest EVOO as a channel for the transfer of scientific knowledge.

In this regard, social innovation as a methodological tool for the transfer of scientific knowledge has also been addressed in various recent case studies in the field of arts-based research [39]. These studies are related to the perspective of the agent of innovation and the social entrepreneur, the creation of new scientific and cultural heritage elements, and a perspective that links art, research and education, in line with the postulates of Irwin [40]. They also deal with the generation of opportunities for disadvantaged groups through the implementation of creative and innovative strategies based on artistic methods.

4. Results and Discussion

Social innovation applied to the case in question is aimed at bringing value to farmers in olive oil producing areas, specifically to those who belong to the Picualia cooperative. Thus, we should first describe the process of selecting and picking the fruit used for this early harvest oil.

A quota system is applied to the harvesting of olives for this product; that is, a specific number of kilos of olive are allocated to the production of this type of oil, stating the exact quality and origin of the fruit. This innovative system has a direct effect in terms of the socioeconomic impact for the farmer. The Table 2 shows the prices per kg of olives paid by First Day of Harvest compared to the average amount paid for harvested olives in each season.

Table 2.

Price comparison between fruit picked for First Day of Harvest and the rest of the harvest.

As can be seen, the average amount paid per kg of harvested olives varies considerably. This is mainly due to the added value from the quotas for harvesting olives for a limited edition EVOO, as is the case with First Day of Harvest. By establishing an average production volume each year, the number of kilos of olives needed can be estimated and a fair price can be paid for them, which in this case is as much as double the price paid for a kilo of olives harvested under normal conditions. In addition, price stability is ensured, which means that by estimating an average price, farmers can invest in improvements to their farms. This in turn has an impact on investment per hectare and accelerates the processes of technification and innovation in producing areas.

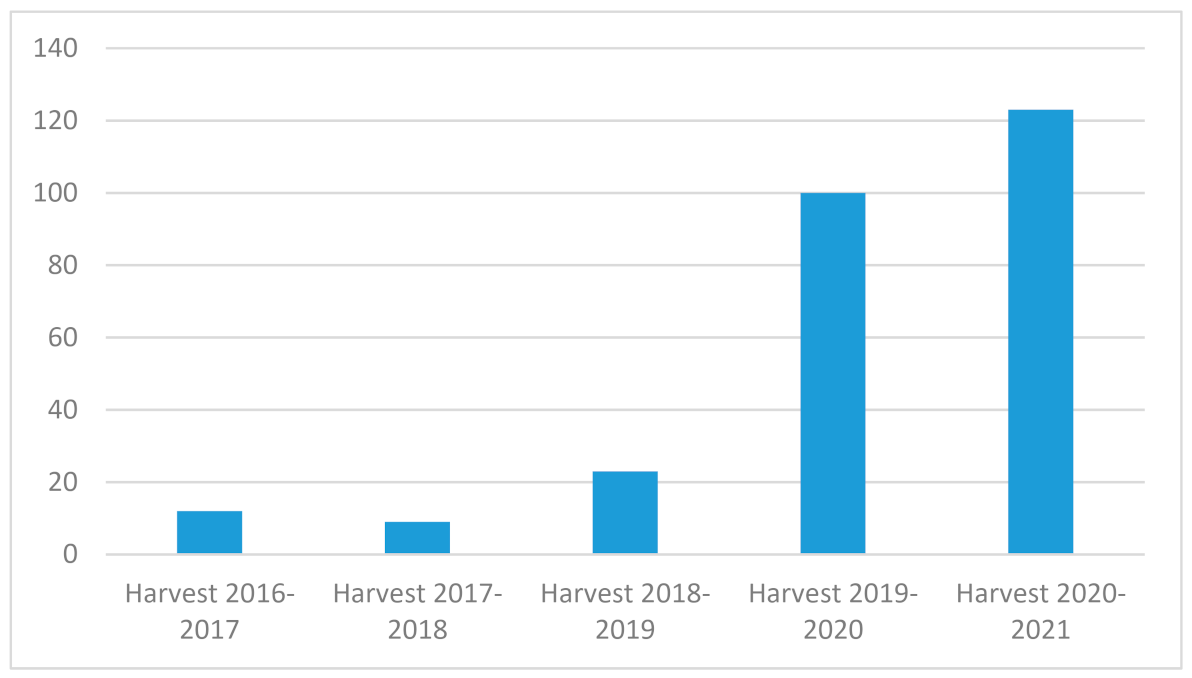

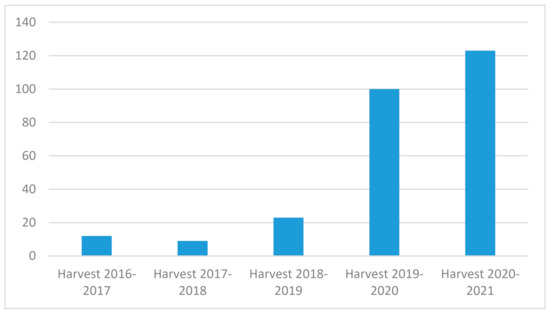

Over time we see an increase in the number of farmers participating in the harvesting of olives for use in First Day of Harvest, particularly in the most recent seasons. The figure below depicts the number of farmers who have joined this initiative.

As shown in Figure 1, there are currently 123 farmers who have been selected to participate in harvesting the olives for First Day of Harvest, representing 13% of the cooperative, compared to the 1% that started this process in the 2016–2017 season. This is a very significant figure, because this initiative structured around social innovation clearly contributes to the development of an olive oil producing area.

Figure 1.

Evolution of number of farmers participating in the olive harvesting process for the First Day of Harvest olive oil. Source: By the authors.

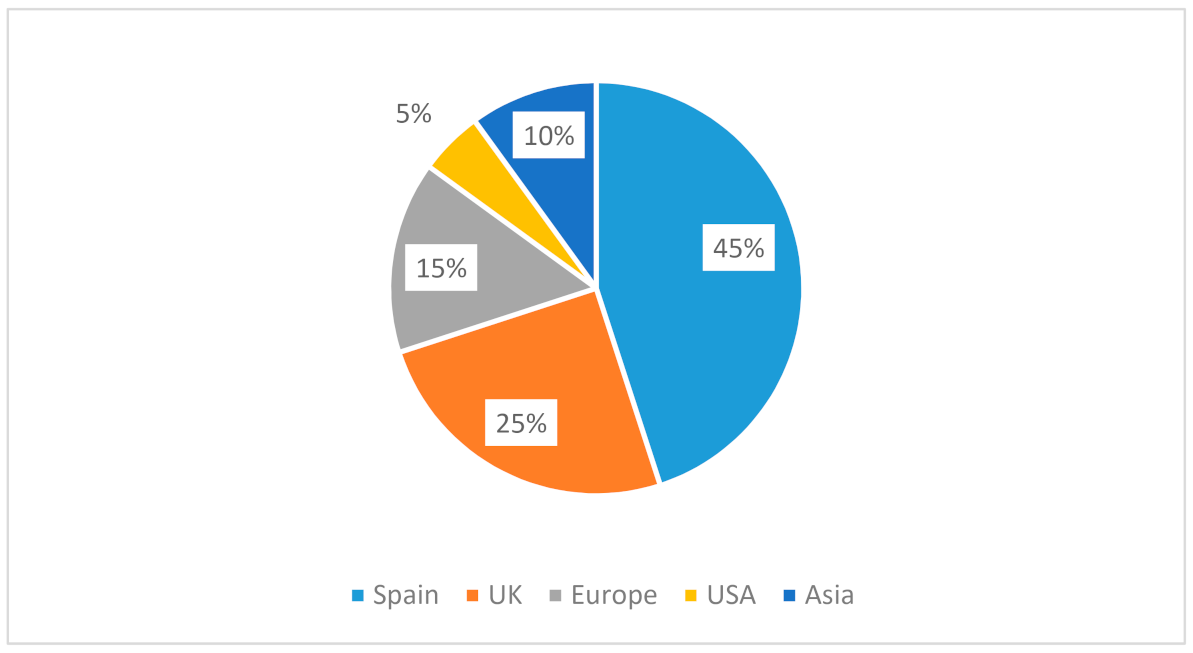

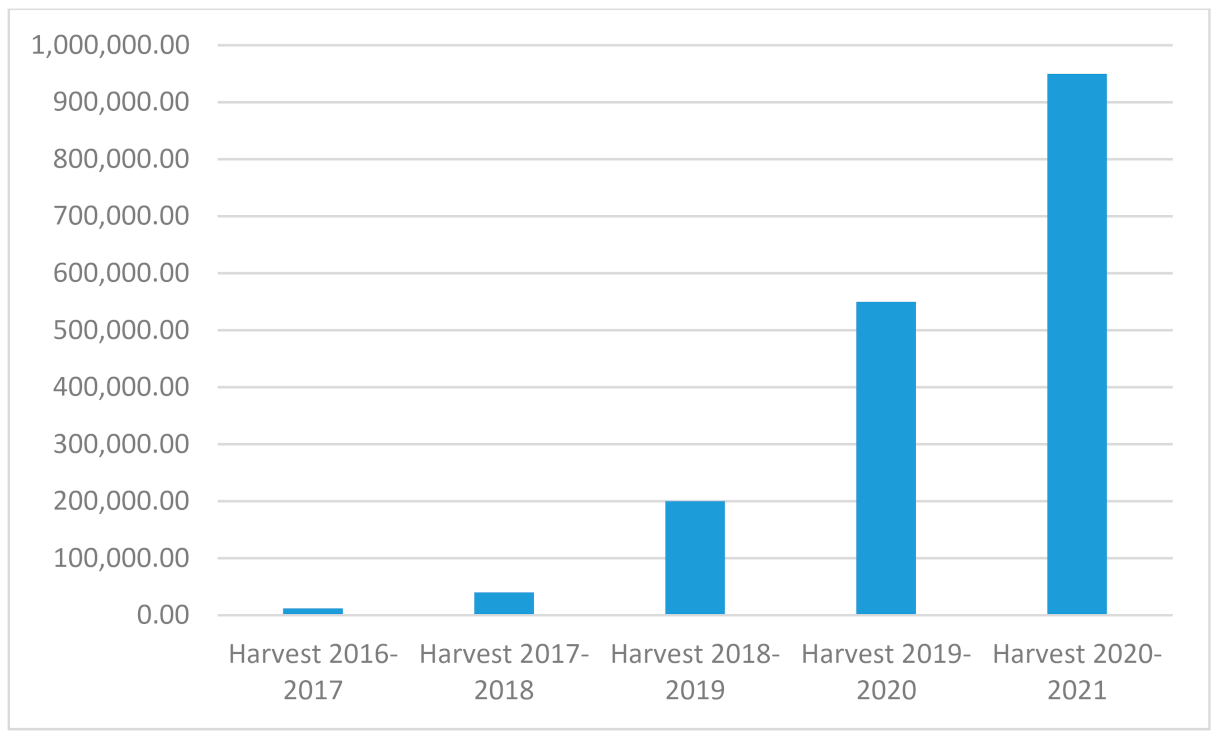

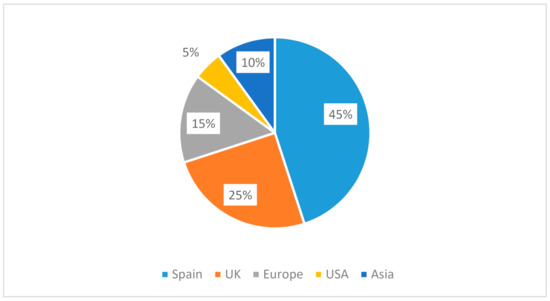

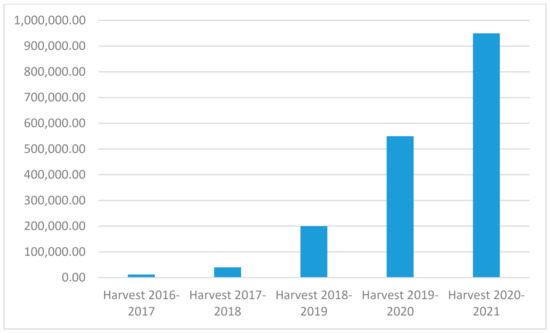

The figures below show the percentage of bottles distributed worldwide during the 2020/2021 season and the annual rise in the number of kilos of olives picked to make the oil to sell to these countries.

Figure 1 clearly reveals the evolution of the volume of olives picked for the production and commercialization of First Day of Harvest. This upward trend reflects the increase in the number of bottles of First Day of Harvest sold both nationally and internationally, as shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. This strong, steady growth is an indication of a clear interest in the project by all the agents involved listed in Table 1; it is particularly important for the local farmers who opt for this type of early harvesting using modern, sustainable techniques and who manage to ensure that their fruit are chosen for the production of this innovative product. Furthermore, this initiative has helped raise brand awareness in a sector as fragmented as that of olive oils; this is demonstrated by the ongoing year-on-year increase in the sale of bottles of early harvest olive oils. To analyse brand awareness in more depth, we provide some context on the thematic nature of this social innovation project below.

Figure 2.

Percentage of bottles of First Day of Harvest sold worldwide 2020/2021 Season. Source: By the authors.

Figure 3.

Percentage of bottles of First Day of Harvest sold worldwide 2020/2021 Season. Source: By the authors.

Figure 4.

Detail of the design of the first label of Picualia’s First Day of Harvest. Source: By the authors.

The Thematic Nature of First Day of Harvest

Focusing on the thematic nature of each edition of Picualia’s First Day of Harvest, we individually address each of the five designs used to date in the Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7. Altogether, Picualia’s First Day of Harvest generates a feeling of rootedness, a sense of belonging to various segments of society. It encourages people to identify with the product and the story to which each limited edition is dedicated. These limited editions disseminate information about conservation projects for endangered species or the results of scientific studies on tangible and intangible heritage; they pay tribute to groups such as farmers or healthcare workers, and they raise funds for scientific research projects. The five labels designed in the period from 2016 to 2020 are detailed below.

Table 3.

First Day of Harvest 2016: the Iberian lynx in the olive grove.

Table 4.

First Day of Harvest 2017: clay, distinctive feature of the local identity.

Table 5.

First Day of Harvest 2018: Tribute to farmers.

Table 6.

First Day of Harvest 2019: the owl, emblematic bird of the olive grove.

Table 7.

First Day of Harvest 2020: Tribute to healthcare workers.

The different labels are signed by the artist, which adds to their interest for consumers, who collect them or suggest new themes through the communication channels used by the cooperative (mostly social networks). In the context of a postmodern consumer society, the appearance of the new editions thus becomes what Bauman would describe as an “event” [41]. The thematic framing of the different editions of First Day of Harvest strengthens the bond with the stakeholders and turns them into product specifiers and brand ambassadors. In addition, a card folded down the middle is tied with a thread to the neck of the bottle. This informative and aesthetic element includes information in Spanish and English on the theme addressed in the edition in question, as well as a thumbnail of the main image of the label and even QR codes linking to the projects chosen to receive a percentage of profits. In this way, social innovation can also be aligned with the objectives of the circular economy, as evidenced by the investigations carried out by Kristoffersen et al. [42], through the use of enabling technologies that can achieve a high impact on this type of Projects.

5. Conclusions

This article has analysed a case study of an olive oil cooperative in southern Spain, exploring the development of a social innovation project involving knowledge transfer and public awareness-raising through the label of an early harvest olive oil called First Day of Harvest. It also assesses the impact of the project on the population of the Andalusian municipality of Bailén (Jaén).

In conclusion, the implementation of social innovation mechanisms and strategies in the sphere of cooperatives and in a rural context, through the project First Day of Harvest, has helped lay the foundations for carrying out actions such as those proposed by Bock [50]; these actions not only enable the achievement of rural development objectives but also help improve production and secure consumer loyalty. Each edition brings with it a rise in the number of customers and geographical locations the product reaches. This leads to a growing number of brand ambassadors, as well as people who are interested in finding out about the process of producing an early harvest EVOO. Olive growers’ involvement in such projects also shows a strong upward trend, as depicted in Figure 1, and this forms the basis of a social innovation project that has improved the company’s commercialization processes, while also:

- Generating creative and artistic innovations framed within the perspective of the “content of social innovation” [24], which have provided added value to the main players involved, as can be seen in Table 1;

- Enhancing the commercialization of products and fostering the strategy for differentiating and building awareness of the cooperative’s brand, in response to the fragmentation of the olive oil industry;

- Proposing joint solutions with social entrepreneurs that promote the development of the territory;

- Establishing an added value project that helps anchor people to the olive oil producing area;

- Promoting fair trade through payments for the harvest with added value for the farmer.

This case represents a model for success in the implementation of projects and strategies for the commercialization of early harvest olive oil. It can thus serve as a reference for other social entrepreneur projects within the cooperative sphere, which in turn have an impact on the productive system in rural areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.P.-G. and D.O.-A.; methodology, D.O.-A.; software, formal analysis, J.A.P.-G.; writing—review and editing, D.O.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Somos Digital. Los Centros de Competencias Digitales del Futuro; Junta de Castilla y León, Tecnalia: Valladolid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://somos-digital.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Los-Centros-de-Competencias-Digitales-del-Futuro.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Mayer, H. Slow innovation in Europe’s peripheral regions: Innovation beyond acceleration. Schlüsselakteure Reg. Welche Perspekt. Bietet Entrep. Ländliche Räume 2020, 51, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Barquero, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. Local development in a global world: Challenges and opportunities. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozas Moral, Adoración. Contribución de las Cooperativas Agrarias al Cumplimiento de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Especial Referencia al Sector Oleícola; Centro internacional de investigación e información sobre la economía púbica, social y cooperativa: Ciriec, España, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Garrido-Almonacid, A.; Gallego-Simón, V.J. Social Innovation in Rural Areas? The Case of Andalusian Olive Oil Co-Operatives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez Martínez, J.D.; Garrido Almonacid, A. Strategic responses of the European olive-growing territories to the challenge of globalization. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2261–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Logroño, P.; Bautista Puig, N. La significación de las cooperativas agrarias en desarrollo del medio rural: El caso de Guissona. In Proceedings of the Coloquio Ibérico de Geografía, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 24–26 October 2012; pp. 1334–1344. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322357515_ in La_significacion_de_las_cooperativas_agrarias_en_el_desarrollo_del_medio_rural_el_caso_de_Guissona (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Montero Aparicio, A. La Economía Social y su Participación en el Desarrollo Rural; Fundación Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes Poyatos, R.; Velasco Gámez, M.M. Importancia de las sociedades cooperativas como medio para contribuir al desarrollo económico, social y medioambiental, de forma sostenible y responsable. Revesco 2009, 99, 104–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas-Moral, A.; Puente-Poyatos, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and its Parallelism with Cooperative Societies. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2010, 103, 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bastida, M.; Vaquero García, A.; Cancelo Márquez, M.; Olveira Blanco, A. Fostering the SustainableDevelopment Goals from an Ecosystem Conducive to the SE: The Galician’s Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Guadaño, J.; Lopez-Millan, M.; Sarria-Pedroza, J. Cooperative entrepreneurship model for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parras, M.; Torres, F.J.; Mozas, A. El comportamiento comercial del cooperativismo oleícola en la cadena de valor de los aceites de oliva en España. In Metodología y Funcionamiento de la Cadena de Valor Alimentaria: Un Enfoque Pluridisciplinar e Internacional; En Briz, J., De Felipe, I., Eds.; Editorial Agrícola: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- AICA, Agencia de Información y Control Alimentarios. Available online: https://www.aica.gob.es/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- COI, International Olive Council. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Moral Pajares, E.; Sanchez Martinez, J.D.; Mozas Moral, A.; Bernal Jurado, E.; Medina Viruel, M.J. Local resources and global competitiveness: The exportation of virgin olive oil in andalusia. Boletin de la Asociacion de Geografos Espanoles 2015, 69, 415–435. [Google Scholar]

- Alimarket, Informes y Reportajes de Alimentación. Available online: https://www.alimarket.es/alimentacion/informe/290401/informe-2019-del-sector-de-aceite-de-oliva-en-espana/15/6f8ef4248d67a51b2e8244508ae810e3 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- BEPA. Empowering people, driving change. In Social Innovation in the European Union; European Commission—Bureau of European Policy Advisers (BEPA): Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, N.; Rojas, A. Una Revisión de las Tendencias en Investigación Sobre la Innovación Social: 1940–2012. Master of Thesis, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Bogotá, Colombia, 29 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Baumann, H.; Ruggles, R.; Sadtler, T.M. Disruptive innovation for social change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. Social innovation: Utopias of innovation from 1830 to the present. In Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation; Working Paper No. 11; INRS: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: http://www.csiic.ca/PDF/SocialInnovation_2012.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Maccallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. The International Handbook. Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.; Tirado, P.; Ariza, A. El Concepto de Innovación Social: Ámbitos, Definiciones y Alcances teóricos. In CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa; 2016; Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/174/17449696006.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Hernández-Ascanio, J. La innovación social como método de investigación participativo y sociopráctico? Tendencias Sociales Revista de Sociología 2020, 6, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiollent, M. Metodologia da Pesquisa-Ação,4ª Edição. São Paulo (SP) in Cortez: Editores Associados. Pesquisa-Ação nas Organizações; Editora Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Nussbaumer, J. Defining the Social Economy and its Governance at the Neighbourhood Level: A Methodological Reflection. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2071–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcy, R.T.; Mumford, M.D. Social innovation: Enhancing creative performance through causal analysis. Creat. Res. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Monzón, J.L. La economía social ante los paradigmas económicos emergentes: Innovación social, economía colaborativa, economía circular, responsabilidad social empresarial, economía del bien común, empresa social y economía solidaria. CIRIEC-España Revista de Economía Pública Social y Cooperativa 2018, 93, 5–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation, 4th ed.; The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Asongu, J.J. Innovation as an argument of CSR. J. Bus. Public Policies 2007, 1, 178–214. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.R.; Searing, E.A.; Brewer, C.V. (Eds.) The Social Enterprise Zoo; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship, The Social Entrepreneurship Fundersworking Group. 1998. Available online: https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Article_Dees_MeaningofSocialEntrepreneurship_2001.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Leick, B. Institutional entrepreneurs as change agents in rural-peripheral regions? ISR-Forsch. 2020, 49, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. La Economía Social: Agente de cambio estructural en el ámbito rural. Rev. Desarro. Rural Coop. Agrar. 2000, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, P.H. Democratizing rural economy: Institutional friction, sustainable struggle and the cooperative movement. Rural. Sociol. 2004, 69, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pérez González, M.C.; Jiménez García, M. Dinámica Territorial y Economía Social: Una Reflexión con Especial Referencia a Andalucía Ante los Cambios Sociales. Revista De Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1). Recuperado a partir de. 2012. Available online: https://150.214.170.182/index.php/REE/article/view/650 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Baselice, A.; Prosperi, M.; Marini Govigli, V.; Lopolito, A. Application of a Comprehensive Methodology for the Evaluation of Social Innovations in Rural Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Alonso, D. Investigación Artística e Innovación Social: Herramientas Para la Transferencia del Conocimiento Científico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, R. A/r/tography. Rendering Self Through Arts-Based Living Inquiry; Pacific Educational Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Arte, Líquido? Sequitur: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kristoffersen, E.; Blomsma, F.; Mikalef, P.; Li, J. The smart circular economy: A digital-enabled circular strategies framework for manufacturing companies. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastón, A.; Blázquez-Cabrera, S.; Garrote, G.; Mateo-Sánchez, M.C.; Beier, P.; Simón, M.A.; Saura, S. Response to agriculture by a woodland species depends on cover type and behavioural state: Insights from resident and dispersing Iberian lynx. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, G.; López, G.; Bueno, J.F.; Ruiz, M.; de Lillo, S.; Simón, M.A. Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) breeding in olive tree plantations. Mammalia 2017, 81, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass-Lindemann, G. Interrelaciones de la cerámica fenicia en el Occidente mediterráneo. Mainake 2006, 28, 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Fernández, J.J. Identidades, Cultura y Materialidad Cerámica: Las Cogotas y la Edad del Hierro en el Occidente de Iberia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J.E. (coord.). Saberes, Artes y Costumbres del Olivar Tradicional. SEO/Birdlife. 2018. Available online: https://olivaresvivos.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Anexo-E4-1.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Flores, L. Atenas, ciudad de atenea. In Mito y Política en la Democracia Ateniense Antigua; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Rey Benayas, J.M.; Pérez-Camacho, L.; Montaña, E.D.L.; Rebollo, S.; Cayuela, L. Effects of land use on nocturnal birds in a Mediterranean agricultural landscape. Acta Ornithol. 2011, 46, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural marginalisation and the role of social innovation; a turn towards nexogenous development and rural reconnection. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).