Abstract

This study sets out to assess the effects of sales-related capabilities of personal selling organizations on individual sales capabilities, sales behaviors, and sales performance in cosmetics personal selling channels. Data are collected from 151 salespeople, their sales organizations, and their visiting customers (151) in South Korea. The proposed hypotheses are tested through the structural equation modelling technique. The study finds that both types of sales-related capabilities (salesforce management capabilities and personal selling capabilities) have significant positive effects on the individual sales capabilities, respectively. Further, the individual sales capability of salespeople has a stronger impact on customer-oriented sales behavior than on selling-oriented sales behavior. Similarly, selling-oriented sales behavior has a negative effect on customer satisfaction while customer-oriented sales behavior has a positive effect. The study further finds that customer-oriented sales behavior has a positive effect, while selling-oriented sales behavior has no statistically significant effect on sales performance. The relationship length, the study finds, moderates the relationship between customer-oriented sales behavior and customer satisfaction. The study offers practical and theoretical insights into understanding the nuances of sales-related capabilities of sales organizations and how they affect the individual selling capabilities of salespeople, their selling behaviors and sales performance. The results also have crucial consequences for sales organizations, as they can help sales managers design strategies and develop a culture that focuses on building and enhancing the selling capabilities of the firm and the salesforce. The present study demonstrates how the selling capabilities of the personal selling organization can influence the individual selling capabilities of the salesperson and how these could engender positive selling behaviors and sales performance.

1. Introduction

The cosmetics industry is a technology-intensive, multi-purpose, small-volume production system with a high participation of small and medium-sized enterprises and a market where sales and brand management are extremely crucial [1,2]. Above all, since it is an industry that manufactures products used for the human body as a field of fine chemistry, it is an industry where basic application technologies such as chemistry, biology, and pharmacy work in tandem. Second, it is an industry where small and medium-sized enterprises can easily enter. Cosmetics are suitable for small-scale production of different types due to short product replacement cycles and diverse consumer groups, and it is easy to enter the market with small capital without manufacturing facilities when using the outsourcing production such as ODM (original design manufacturer). In this sense, the cosmetics industry can be seen as an industry with high participation of small and medium-sized enterprises. In fact, about 89% of cosmetics manufacturers and retailers in South Korea are small and medium-sized enterprises, with sales accounting for 48% of the total cosmetics market [2].

Additionally, the marketing cost is very high because the branding is important as a key purchasing factor for consumers. According to Amore Pacific, the number one cosmetics company in South Korea, sales costs accounted for 27% of their total cost structure, while sales and management costs accounted for 61%. Looking at the factors that make up sales and management costs in detail, marketing costs such as distribution fees and advertising costs are very high, with distribution fees at around 26.2%, advertising fees at around 18%, payment fees at around 14.8%, and others at around 41% [3].

Ref. [3] announced the share of sales by the cosmetics sales channel and, per the result, online shopping malls (18.9%), door-to-door sales (15.2%), general retail stores (12.5%), duty-free shops (11.8%), and brand shops (11.0%) emerged in that order. In the case of door-to-door sales channels, there is little change in the share of sales per channel and it remains above 15.0%. It is therefore not an exaggeration to say that the distribution structure of the South Korean cosmetics market has been significantly affected. Due to the peculiar nature of the sale of cosmetic products, research on the sales capabilities of door-to-door sales organizations or door-to-door sales personnel can be seen as very important both practically and academically.

South Korea’s cosmetics market is the eighth largest in the world and its average annual growth rate from 2012 to 2016 was 16%, which is more than five times the average annual growth rate of the Korean economy of 3% over the same period [3]. Of course, the growth of the cosmetics industry has slowed slightly in recent years due to the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) conflict and the decline of Chinese tourists in 2017. However, South Korea’s export of cosmetics was valued at USD 5.32 billion, up from 4.92 billion dollars in 2018. Revenue on the South Korean beauty and personal care market amounted to US$11,500 million in 2020 [4]. Entry and growth are in full swing, and major brands are accelerating to Asian markets, including China, so it can be seen as an industry with very high growth potential.

However, despite the crucial role of salespeople in the cosmetics industry and how it generates sales behavior and results, this role has not been fairly represented by previous research, creating significant deficiencies in current literature. Previous researchers have asserted that, to date, only 4% of academic research related to sales in marketing research has been published, and among these studies, research focusing on the door-to-door sales channel is very low [5,6]. Further, previous research on salespeople have focused on issues such as adaptive selling behavior [7], self-efficacy beliefs and direct selling sales performance [5], salesforce effectiveness [6], among others. Research that examines how the organizational capabilities of sales organizations influence the personal capabilities of salespeople and how this further engenders sales behaviors and performance in the context of door-to-door selling is virtually non-existent, which further accentuates the need for fresh research aimed at filling these gaps.

To this end, this study focuses on both organizational and personal variables that affect the sales performance of door-to-door salespeople in cosmetics personal selling organizations. Organizational sales management focuses on the sales-related capabilities of sales organizations, which has received little attention by previous researchers. In effect, we demonstrate the impact of sales management capabilities and personal selling capabilities of sales organizations on salespeople’s sales behavior and sales performance through salespeople’s individual sales capabilities. In addition, because most of the existing studies relating to the capabilities and performance of salespeople have limitations of the self-reporting method of salespeople [5,8], this study uses the actual sales performance data of individual door-to-door salespeople, customer-reporting of the salespeople, as well as salespeople’s self-reporting responses. This differentiated approach to data collection and analysis is the methodological point of departure of this study.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Resource-Based View

Many marketing studies have adapted the resource-based theory to explain the relationship between the differentiated competitive advantage of companies and marketing performance [9,10]. The resource-based theory suggests that the performance of a company is determined by internal resources and capabilities, but not by external factors such as economics or attractiveness [10]. This theory has been used in the marketing sector since the 1990s [11,12]. The theory emphasizes the importance of resources to the organization. It suggests that the company’s resource adds positive value to the organization (valuable), is rare/unique (rare), and inimitable (inimitable) to the extent that potential competitors do not have access to it now and in the future. Emphasis is placed on securing resources or capabilities that have non-replaceable properties with other resources secured by competitors [10]. This is difficult to imitate because of the foregoing characteristics, which are distinguishable from resources that can be easily transferred and secured to other organizations. Scarcity prevents other organizations from easily acquiring the same resources, making it impossible to create a fully competitive situation.

Ref. [10] categorized resources into physical capital, human capital, and organizational capital on the basis of heterogeneity and immobility. These resources are not a temporary competitive advantage for a company, but a sustained competitive advantage. In particular, he highlights the importance of human capital among the three resources. Traditional resources, such as natural resources, technological resources, economies of scale, etc., have, in the past, made it possible for an organization to have a competitive advantage in the context of the resource-based theory, but these resources can easily be imitated by competitors and transferred to other resources. [10] averred that it is no longer a valuable resource because it could be replaced and that it is important to secure human resources in order for the organization to be competitive. In addition, human capital, a source of sustained competitive advantage, can be explained as an important factor in corporate performance [13]. Consequently, the delivery of human capital, an invisible and intangible resource through education, is a source of corporate competitiveness. The resource-based theory has been used in previous studies [14,15,16] and is accordingly applied to the current study.

2.2. Sales-Related Organizational Capabilities

Sales Management Capabilities in Organizations

Ref. [17] posited that the sales capability of the organization is influenced by the organizational situation of the company as a capability that refers to the heterogeneous resources of the company (sales personnel size, sales force replacement rate) and ability. In their study that focused on the strategic role of the sales organization aimed at senior management in the sales division of the company, ref. [18] found that the ability to acquire new customers and build customer trust were among the strategic roles of the sales organization. These were presented in the form of five capabilities: Responsiveness to demand; the development of customer relationships; the ability to acquire new customers; the building of customer trust; and customer retention. These five capabilities are a complex knowledge-based process with primary responsibility on the part of the sales organization. It utilizes and integrates the resources of the sales organization and the company and focuses on the customer-facing process and the desired outcomes of the customer [19]. Ref. [7] captured sales management capability in the following forms: First, sales force structuring capabilities in consideration of the strategic and long-term oriented areas of the sales force structure, including the size and organization of sales manpower, recruitment, and training of human resources; second, talent management in the management area; and third, customer targeting as a coordination area of sales activities for products and markets, and the impact of these sales management capabilities on corporate performance. The next session delves deeper into these forms.

First, the structuring capability of the salesforce is the process of assigning clear roles and responsibilities to the members, and the composition of the sales organization is mainly how many sales personnel should be secured, and which products should be assigned to the sales personnel and the company. It involves determining how many total salespeople should be acquired or whether to have full-line salespeople or salespeople who sell specific products [20]. When these salesforces are organized in the right size, salespeople will operate in regions with a balanced and acceptable workload and market potential [21] and will be able to do their jobs with sufficient time to regularly contact customers and discuss issues that need to be resolved [22]. This implies that if the sales force structure is properly defined, salespeople can maximize their individual capabilities in working with customers.

Second, talent management consists of three sub-elements: Hiring, training, and sales management [17]. In the resource-based theory, these core talents can be defined as those with capabilities and abilities that are difficult to imitate and are difficult to replace by other companies, which becomes the source of corporate value creation and sustained competitive advantage and has been described by [10] as human capital. Unlike the traditional industrial society, in a knowledge-based society, the ratio of key talents to contribute to corporate value creation and productivity improvement is considerably higher. Therefore, how to secure and maintain key talents is emerging as a major management issue for managers [23,24,25]. The management of these core resources is divided into securing and retaining key talents, and most of the research on the management of core talents in an organization is about securing, recruiting, nurturing, and retaining key talents [26]. Studies on the relationship between management of human resources within an organization and corporate performance emphasize the inevitability of active core talent management, arguing that companies that manage key talents outperform those that do not [26]. In hiring and managing salespeople in the organization, recruiting, training, and managing any talent will have a significant impact on the business and customer performance of the company. In particular, the importance of managing salespeople in the personal selling market that faces customers is emphasized, and the management of hiring, training, and motivation of salespeople in the personal sales organization is used as a key management indicator of the organization.

Finally, customer-targeting capability refers to the ability of a company to present customers to whom sales representatives can make proposals, segment customers by region and product, and select target customers in the right way that is appropriate for each customer [27]. It also represents the ability to select a sales model [17]. The selection of a clear target customer and a sales model tailored to each customer act as an important variable in sales performance in the creation of new products or new customers. Customer segmentation refers to the process of dividing all customers with different needs into homogeneous customer groups according to certain criteria [28]. Customer segmentation enables customer groups to be segmented according to their value trends and characteristics, and to develop an appropriate marketing strategy based on the differences in value trends and characteristics of each segment [29].

In effect, the sales management capability of such an organization will have an impact on the sales capabilities of salespeople, and this will have an impact on the performance of the company. This study therefore focuses on analyzing the relationship between the sales management capability of the organization and the individual sales capability of the salesperson in relation to sales performance.

2.3. Personal Selling Capability in Organizations

Ref. [17] viewed the process function of sales as a customer-centric process primarily performed by salespeople. These sales process functions integrate sales and company resources and have a direct impact on performance. This function is an important sales process with a high level of organizational capability related to customer relationship management by combining sales, service, and relationship management. In the case of salespeople performing sales activities, the human sales capability of the organization provides direction to salespeople and provides the basis for sales performance. Ref. [30] argued that selling skills and interpersonal skills are the two basic elements of interpersonal sales capability. Ref. [7] surmised that personal sales are no longer a single activity managed by individual salespeople. Similarly, ref. [31] posited that the sales field is moving away from the sales function and operational attitude, which is the sole activity of salespeople, to the process, which is an integrated activity.

While selling, salespeople develop individual sales capabilities by interacting with the company and customers, communicating with customers, and delivering results. It has been proposed that such personal sales capabilities be divided into sales technology and customer management [7,32]. In terms of human sales capability, salesmanship is the cross-selling and up-selling task, which is a method of inducing more sales to customers, delivering accurate sales messages, and closing sales. It is explained as a branch, and that customer management (account management) consists of two aspects: Building customer relationships and maintaining customer relationships.

Ref. [33] presented sales skills-related capabilities (communication skills, sales visit preparation skills, expertise, etc.) as skills and capabilities to be developed in the training course for sales personnel. The sales organization continuously promotes efforts to improve sales-related techniques as well as professional knowledge of products through training. Through this, salespeople improve their sales skills and performance.

2.4. Sales-Related Individual Capability & Sales Behaviours

2.4.1. Salesperson’s Individual Sales Capability

A salesperson refers to a person in charge of personal sales who, in order to induce the purchase of goods or services, contacts, provides, persuades, and arouses demand from customers or prospective customers [34,35]. These salespeople play a boundary-spanning role that connects buyers with corporate activities essential for the success of corporate marketing activities between companies and buyers and performs various innovative and creative activities for this [36,37]. Hence, since all sales are made through a salesperson, the salesperson plays an important role as a facilitator who directly contacts and persuades prospective customers to purchase a product or service.

Since salespeople in such a personal sales context oversee direct contact with customers, provide information, and persuade customers in selling products or services, they must have a great deal of knowledge about the products they sell and be aware of their customers [38]. A formidable salesforce plays a vital role in developing positive customer value through nurturing sustainable relationships with customers. These behaviors of salespeople contribute to creating sustainable benefits for customers and the firm as a whole. In addition, because the company image is first formed by salespeople who are in direct contact with customers, the role of salespeople in human sales is very important. This implies that salespeople must not only sell products to consumers, but must also play a role in making customers partners who contribute to the creation of corporate profits [39,40]. A systematic study of the capabilities of sales staff began in the 1990s when the general capability model began to be seriously studied. Ref. [41] are representative scholars who have presented the capabilities of sales personnel and are most frequently cited in the study of salesperson capabilities. Ref. [41] classified individual capabilities by job type in the capability model into three types: Technical/professional, sales, and interpersonal service, and compared the capabilities and behaviors of excellent performers and average performers by grouping them into individual employees and managers. Their study found that the competence of excellent salespeople varies depending on the length of the business cycle, complexity, regional characteristics of the company, products, and types of customers. The competences that salespeople must have are influenced by control, achievement orientation, initiative, and inter-personal skills [42]. They also found understanding, customer orientation, confidence, relationship formation, analytical thinking, conceptual thinking, information establishment, organizational awareness, and technical expertise as key capabilities for salespeople. This sales capability contributes decisively to performance generation and improvement among numerous capabilities. It is the most faithful and appropriate capability for the purpose of the organization at the organizational level, and the capability most suitable for individual roles or responsibilities at the individual level [43].

Relative to the constituent factors of the sales capability of individual salespeople, various detailed factors have been proffered by previous researchers. For instance, ref. [44] proposed the ability of sales representatives to understand customers for strategic sales activities, the ability to prepare strategically and systematically, the ability to propose for various communications with customers, and to improve sales productivity. Insisting that information gathering capability is a detailed factor of sales competency, ref. [45] maintained that partnership with customers, relationship formation, communication, customer and quality orientation, learning motivation, achievement orientation, interpersonal skills, internal resources and network utilization, and technical capabilities such as management ability and problem-solving ability are all key constituent parts of sales capability. Sales capability is an individual’s or organization’s own capacity that plays a decisive role in achieving performance or creates a competitive advantage [46]. This is not something anyone can easily imitate because it is a unique and innate ability. Moreover, it is more difficult to imitate because it exists in the form of core knowhow, knowledge, and technology, and it is not just an individual or an organization, but an inherent characteristic. We can therefore argue in the case of sales organizations that it is very important to ensure that salespeople have a high level of sales capability. Existing sales studies have indicated that effective sales strategy activities can promote sales performance and ultimately improve management performance [47,48].

2.4.2. SOCO (Sales-Oriented and Customer-Oriented) Behaviors

Ref. [49] classified the two ways in which salespeople interact with customers into sales orientation (SO) and customer orientation (CO) and designed the SOCO scale for measuring same. They noted that customer orientation is the degree to which salespeople strive to help customers make satisfactory purchase decisions, thereby practicing the marketing concept, and that sales orientation is a selling approach that aims at selling to customers as much as possible. Customer-oriented salespeople are therefore interested in learning how to understand customers by paying attention to consumer needs, and on that basis, are interested in providing the best solutions to consumer problems, not just simple sales. On the other hand, sales-oriented salespeople tend to rapidly maximize their short-term profits [49,50]. However, it is important to understand these two concepts to the effect that a high level of customer orientation does not necessarily accompany a low level of sales orientation. People are driven by motives such as concern for others, including the motives for pursuing their own interests and altruistic tendencies [51]. In this regard, it can be said that customer orientation and sales orientation are not mutually exclusive.

Early research on the preceding customer orientation factors focused mainly on the personal characteristics of salespeople [47]. Similarly, a study on the impact of characteristics on customer orientation was conducted and, as a result of a series of studies, it was found that the type of leadership, sales control, or monitoring method, etc., influence customer orientation [52].

Sales orientation is a business approach that aims to sell to customers as much as possible, and it focuses on closing a transaction with a customer in real time. Regarding customer orientation, it is emphasized that in contrast to the forced, short-term intensive sales method, the aim is to avoid behavior that hinders customer satisfaction and profits in order to increase immediate sales by focusing on long-term customer relationships. The concept of sales orientation has been considered to be non-customer-oriented.

However, [49] clearly set out the situation in which customer orientation is effective in the same study and reckoned that this concept is valid at anytime, anywhere, and does not position it as a concept that replaces all sales activities. The customer-oriented selling approach is inevitably costly. It can only shed light on situations where the utility exceeds the cost [49]. In other words, it can be judged that the sales-oriented approach will continue to work in the rest of the situations.

Ref. [53] argued that customers have both short-term and long-term preferences such that, to maximize performance, companies can achieve sales by satisfying the expressed needs of customers in the short term as well as by capturing and satisfying potential needs. In addition, ref. [54] applied a meta-analysis approach to analyze the determinants of the performance of salespeople in a sales research over a 75-year period. They noted that talent is a personal trait, and it was recognized as the most important determinant demonstrating that the execution of capabilities such as selling skills are important factors in enhancing performance in addition to consumer relationship development, attitude, and needs identification. Recently, ref. [7] also argued that the combination of salesperson’s adaptive selling and selling orientation can have a positive effect on the customer’s trust in the salesperson. Their research found that the relationship period between salespeople and the importance of the purchased product can have a moderate effect.

This study departs from previous sales research that appears biased around customer-oriented and allied concepts and analyzes the selling behavior of sales personnel in both customer-oriented and sales-oriented directions and scrutinizes the effect of these selling behaviors on sales and customer performance.

3. Hypotheses and Research Model

The resource-based theory [10] is relevant and applies to the present research in that the organization’s sales management capability and personal selling capability are recognized as unique capabilities that other companies cannot easily imitate and acquire. In particular, salespeople with excellent personal selling capabilities formed by these organizational capabilities can be a source of competitive advantage as a key resource in resource-based theory to secure the company’s competitive advantage and deliver results. This puts this theory perfectly within the scope of the current study and has been adopted as the theoretical lens for same.

3.1. Sales-Related Capabilities of Sales Organizations and Individual Sales Capability

As described above, the sales management capability of the organization consists of the structuring of the salesforce, customer targeting, and talent management [7]. Salesforce structuring capability is an organizational capability that determines the size of a sales organization [20]. When the salesforce within the organization is well-organized, they will operate in an area with a balanced and acceptable workload and market potential [21]. These salespeople will be able to do their jobs with sufficient time to contact customers on a regular basis and discuss issues that need to be resolved [22]. This implies that if the salesforce structure is properly defined, salespeople can maximize their individual capabilities in working with customers.

Talent management consists of the recruitment, training, and management of human resources. Knowledge is the core resource of an organization from the resource-based theory perspective [10]. More specifically, it suggests that the ability of a company to apply integrated knowledge to business processes from a competency-based perspective improves efficiency and effectiveness [55], a position that [56] clearly highlight in their research on core talent management. Top talent is difficult to imitate by other companies and has characteristics that give them a sustainable competitive advantage. Acquisition, development, and retention of human resources in a sales organization have positive effects on organizational performance [52]. This is the composition of a sales organization of an appropriate size to maximize the individual capabilities of salespeople, with an eventual positive impact on corporate performance. Ref. [57] asserted that when human resource management is carried out in line with strategic choices, the flexibility of the commitment and capacity of the members increases, affects the attitudes of the members and, ultimately, increases the financial and non-financial performance of the organization.

Customer targeting highlights a company’s ability to segment customers, select target customers, and select a sales model suitable for customers [7]. In terms of the efficiency and effectiveness of resource allocation, firms spend more time and effort on their customers, use various methods of understanding customer needs, and increase the likelihood of generating a lot of sales when salespeople develop customer value propositions and meet customer needs. The likelihood of success in coordinating customer care processes increases [58]. Customers react differently to the same marketing strategy provided by companies, depending on individual characteristics and psychological factors. Hence, in order to establish an effective marketing strategy, companies need to understand the characteristics of various customers and present strategies that match the characteristics of customers. Customer segmentation provides different marketing activities to customers in different groups, aimed at increasing customer satisfaction. In other words, customer segmentation is widely used by companies to provide more suitable marketing strategies for different customers by enabling them to understand dissimilar customers more accurately and to develop and execute marketing strategies efficiently and effectively [59]. Customer segmentation is useful for selecting target customers to offer promotions and to sell products or services. Selecting target customers through such customer segmentation and proposing customized sales models is more effective and efficient in creating corporate performance. In other words, customer targeting capabilities have a positive effect on customer satisfaction and corporate performance. The organization’s sales management capability will affect the salesforce’s ability relative to sales activities and, through this, it is believed that it will have a positive effect on customer satisfaction and corporate performance.

Personal selling capabilities consist of account management and sales management [7]. Customer management capability consists of building and maintaining customer relationships. Sales technology consists of cross-selling and up-selling, delivering accurate sales messages and closing sales. Customer management activities are meant to maintain a continuous relationship between the company and the consumer, in order to increase the performance of the company. To do so, the relationship benefits that can be achieved while the relationship continues should be pursued. These relationship benefits are the fundamental benefits of the core services that companies provide to consumers in order to develop and maintain relationships with consumers, as well as all kinds of benefits provided to consumers [60,61]. In line with the foregoing, ref. [62] emphasized that the efficiency of consumer decision-making is increased through a sustained relationship with a company. If consumers maintain a relationship with a company, transaction costs, psychological costs, and time costs will not only decrease but it has been suggested that purchase risk reduction, socialization benefits, and individualization benefits will be achieved in the long term [63,64].

Marketing and sales performance models emphasize that a company’s actions have a sequential effect on the performance indicators of different organizations. Ref. [65] claimed that marketing activities have a sequential effect on customer impact, market impact, and financial impact. Similarly, ref. [6] found that the sales process is influenced by organizational drivers such as structuring, technology development, and customer prioritization, which affect customer performance and give priority to company performance, such as market share and revenue. On the basis of these theoretical foundations, it can be argued that the sales management capability and individual sales capability of the organization will directly or indirectly affect the performance of the organization. The sales management capability and individual sales capability of an organization will have a direct impact on the customer and market-based performance. However, the capabilities and performance of these organizations are achieved through salespeople. In particular, customer management and the personal selling capability will improve the sales capability of salespeople, which will lead to market performance. Accordingly, the following set of hypotheses is proffered.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The salesforce management capabilities of the cosmetic door-to-door sales organization will have a positive (+) effect on the selling capability of the individual salesforce of door-to-door sales organizations.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The personal selling capability of the cosmetic door-to-door sales organization will have a positive (+) effect on the selling capabilities of the individual salesforce of door-to-door sales organizations.

3.2. Individual Sales Capability of Door-to-Door Salesperson and SOCO

Ref. [41] contended that capability is an indicator of the behaviour and mentality that employees must consistently demonstrate in order to achieve performance in a variety of job-related situations. It is defined as a collection of technical attitudes or indicators that can be improved and measured through continuous development and performance in important areas, and capability is said to be centred on the specific behavioral characteristics of individuals in the work process [43]. In order to become a good capability, it is argued that specific actions in the process of performing work are required, along with the professional knowledge, skills, personality and mentality of the individual that are necessary for high performers [66]. Individual capabilities, such as knowledge and skills, influence individual behavior in the production of good products and services and enhance organizational performance [67]. In keeping with these previous studies, we argue that the capability of individuals in the organization influences performance through individual actions. We note that in the sales organization, the individual sales capability of the salesforce is revealed by their selling behavior.

Concerning sales-related capabilities, ref. [41] provided a systematic standard for job capability required to achieve organizational goals and revealed that the most important capabilities in the sales job are achievement orientation and influence. Ref. [44] reckoned that providing training for sales staff who need to carry out long-term sales activities based on factors such as an understanding of the changing environment, customer management capability, relationship formation ability, ability to prepare for business visits, communication skills, ability to establish long-term customer relationships, and information gathering ability were extremely vital. Looking at the aspect of individual sales capability, it can be seen that customer management, customer relationship formation, and long-term relationship aspects are mentioned more than the factors for achieving short-term sales performance. On the corporate side, rather than focusing on short-term sales performance, it focuses on organizational capabilities to strengthen relationships with existing customers. Salespeople with high sales capabilities value short-term sales as well but will achieve higher performance through long-term relationships with customers that the organization values. In particular, long-term awareness of long-term relationships is important to salespeople in the personal sales market, which values relationships with customers, and sales organizations that reflect indicators of relationships with customers as performance reinforce salespeople’s customer-oriented sales behavior. Based on the foregoing, the following hypothesis is set:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Cosmetic door-to-door salespersons’ individual sales capabilities will have a stronger positive effect on customer-oriented sales behaviour than on sales-oriented sales behaviour.

3.3. SOCO, Customer Satisfaction, and Sales Performance

Customer orientation, which refers to a company’s management policy and philosophy that creates a competitive advantage by focusing on and fulfilling customer needs, is represented through mutual work with customers and satisfaction of customers’ needs in the purchase decision-making [68]. It can be viewed as a behavior related to customer service provided by customer contact employees for that purpose. Ref. [69] stressed that customer orientation has a positive relationship with the rate of change in relative market share, new product success, and overall performance. Until now, most studies on personal selling and sales management have suggested that customer orientation has a positive effect on sales performance [48,70,71].

Ref. [49] suggested that the customer-oriented-sales-oriented concept is relatively effective for improving performance, especially in situations where the sales orientation is effective, purchasing is not repetitive, the salespeople’s expertise is relatively low, and the task is low. In addition, ref. [53] argued that customer preferences are divided into short-term and long-term forms. Sales-oriented sales behavior is rather effective in satisfying customers’ short-term preferences, and salespeople do not change various conditions and circumstances in the short-term. Instead, they argued that it could contribute to the organization’s performance via reducing sales by persuading customers only with currently available conditions. In fact, sales-oriented salespeople tend to be driven by external compensation, so if there is an adequate evaluation and compensation system in place, they will work hard to earn compensation and recognition and strive to improve performance during the period [72,73], which will eventually lead to an increase in corporate performance.

Although the sales orientation of salespeople has a positive effect on performance, the long-term and short-term performance may have different effects. In particular, since sales orientation is seen as a sales approach that maximizes corporate profits by focusing on short-term preferences of consumers [53], it is expected that the effect of sales orientation on short-term performance is greater than that of long-term performance. Salespeople with customer orientation work hard and smart to satisfy customer [71]. However, since these actions are aimed at building relationships with customers from a long-term perspective, they inevitably entail a lot of time and money [49], and they can deliver customer satisfaction and profits even if immediate sales results do not occur [58,74]. In the door-to-door sales market, where customer satisfaction and sales performance are achieved through direct visits to customers and relationships with customers, intimate relationships with customers play a major role in achieving performance. Consequently, based on the preceding discussions, we argue that the influence of salespeople’s customer-oriented sales behavior and the performance of sales-oriented sales behavior could be different and, hence, the following set of hypotheses is advanced:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Customer-oriented sales behavior of salespeople at cosmetic door-to-door sales organizations will have a stronger positive (+) effect on customer satisfaction than sales-oriented behavior.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Sales-oriented sales behavior of salespersons at cosmetic door-to-door sales organizations will have a stronger positive (+) effect on short-term sales performance than customer-oriented sales behavior.

3.4. Moderating Effect of Relationship Length on the Relationship between SOCO and Customer Satisfaction

Previous studies related to the relationship length have indicated that mutual benefits, social benefits, satisfaction, and loyalty increased according to the length of relationship [7]. The social benefits perceived by long-term customers are higher than those of short-term customers [75]. Similarly, employee satisfaction, word of mouth, and loyalty to the company are found to be high within the context where the length of relationship is higher [75]. Interactions that occur repeatedly between customers and service providers induce human relationships, which strengthen the ties between customers and service providers, affecting perception of service quality and the possibility of conversion to service providers [76]. Prior studies related to relationship marketing have also underscored that the influence of relationship-linking factors for relationship formation can be influenced by the duration of the relationship [77,78]. Ref. [79] surmised that in the case of satisfied customers, as the relationship period increases, the relationship benefits increase, and the customer retention rate also increases. Ref. [80] opined that customer trust develops into loyalty through the process of a relationship over time.

Companies want to retain customers over the long term [63]. Therefore, they make attempts to actively preserve them. From the point of view of the consumer, they consider the relationship to be beneficial due to the rise in relationship benefits and the reduction in information search costs, etc. The differentiation of door-to-door cosmetic sales in the current distribution channel is that sales representatives meet customers directly and provide customized services such as product consultation, skin care, and make-up. This advantage will have a greater impact as the length of the relationship with the customer increases. Therefore, customer-oriented sales behavior based on the customer-oriented way of thinking will be moderated by the relationship length, relative to customer satisfaction and sales performance.

Customers’ preferences are divided into short-term and long-term; and sales-oriented sales behavior is rather effective in satisfying customers’ short-term preferences [53]. Sales-oriented behavior will affect customer performance and sales by satisfying these customers’ short-term preferences. However, if the relationship period continues, the performance due to short-term preferences is expected to decrease due to long-term relationships with customers. Accordingly, sales-oriented behavior of salespeople will have a negative moderating effect on customer satisfaction and sales performance if the relationship period continues. Consequently, the following hypothesis was derived.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

The effect of individual customer-oriented and sales-oriented sales behavior of salespeople on customer satisfaction will be both positively (H6a) and negatively (H6b) moderated by the relationship length at the cosmetic door-to-door sales organization.

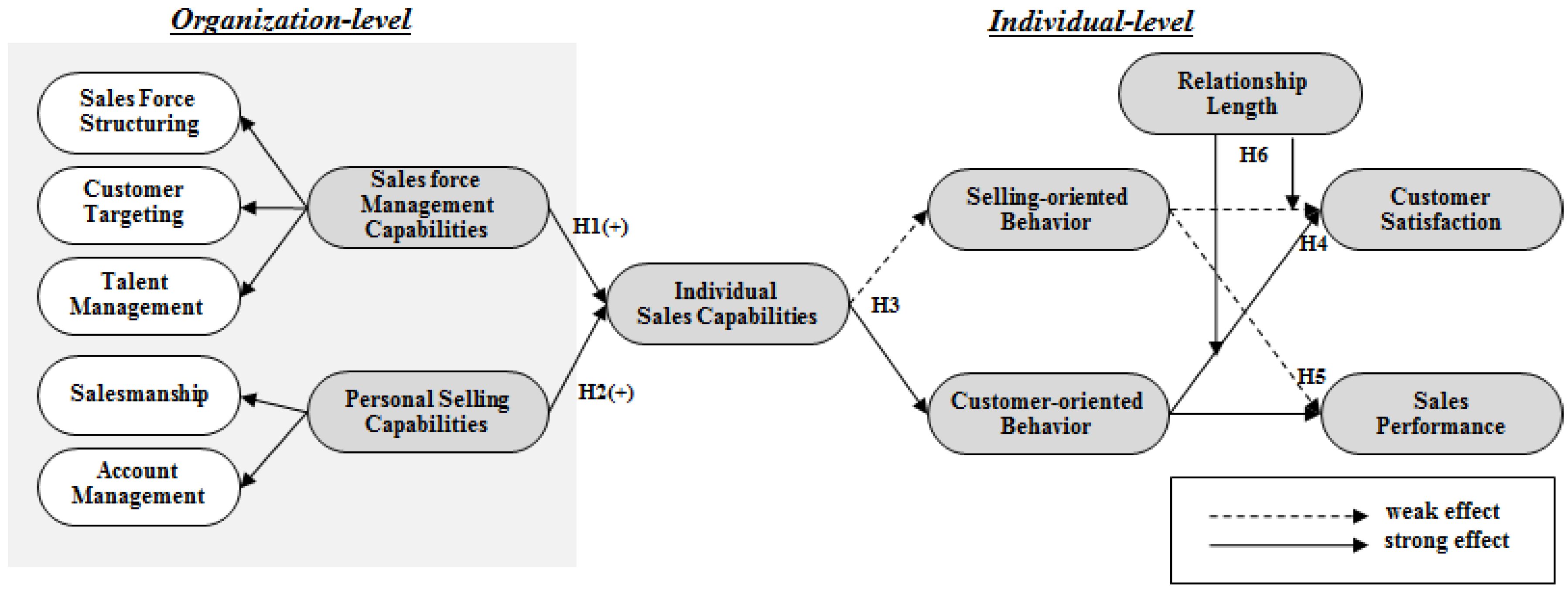

3.5. Research Model

The present research aims at investigating the effects of sales-related organizational capability (in the forms of salesforce management capabilities and personal selling capabilities) on the salesperson’s individual sales capabilities and how that influences both the sales- and customer-oriented selling behaviors of the salesperson as well as how these two (SOCO) affect both customer satisfaction and sales performance while evaluating the moderating role played by relationship length. This is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Empirical Test and Hypotheses Analysis

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

To verify the hypotheses set out in this study, a questionnaire was administered to 151 door-to-door salespeople belonging to two different cosmetics companies that operate door-to-door sales channels, ranked first and second in the South Korean cosmetics market. In this study, data from door-to-door salespeople, customers of the door-to-door salespeople, and sales performance according to the measurement items were based on actual sales data of the relevant door-to-door salespeople. Data collection took place between August to December 2020, and it was face-to-face. Respondents decided to take part in the research after the research objectives had been explained vividly to them. The characteristics of door-to-door salespeople and customers who responded to the questionnaire are as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Description of respondents.

4.2. Measures

The variables and measurement items used in this study are all variables that have reliability and validity because they have been used in previous studies. However, there are items that are used for the first time in domestic studies and are partially modified to suit the characteristics of the relevant industry for application to the cosmetics industry. The measurement items are as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement items.

Test for Non-Response Bias

We tested for non-response bias by comparing early and late respondents on work experience, work position, education, and company name. Second, we looked for differences between the variables of the two groups used in this study. In either case, no significant (p < 0.05) differences were found.

4.3. Reliability and Validity Test

In the present study, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was used to verify the reliability of the measurement items through internal consistency, and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to ensure its validity. Among the measurement variables, the salesforce management capabilities, personal selling capabilities, and individual sales capabilities were measured by second-order variables and provided by the door-to-door salespeople, the salespeople’s customers, and the organization to which the salesperson belonged relative to the characteristics of the variables. This is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis and Cronbach’s alpha test.

Since all the measured variables have Cronbach’s alpha values of at least 0.8, internal consistency was established. The analysis results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify the single dimensionality of the measurement items are χ2 = 1003.534, d.f. = 644, χ2/d.f. = 1.558, RMR = 0.032, GFI = 0.830, IFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.933, CFI = 0.941. The chi-square value shows the change according to the increment or decrement in the degree of freedom and should be less than 3 in order to satisfy the overall degree of fit. RMR is less than 0.05, while IFI, TLI, and CFI are all more than 0.90. It could therefore be confirmed that the overall fit of the theoretical model to the factors set out in this study was good [81]. The standardized loading value linking the measurement item and the corresponding factor, as well as the AVE, which measures the amount of variance explained by the research unit, were also more than 0.5, emphasizing centralized validity.

In order to ensure discriminant validity, we examined whether the square value of the correlation coefficient between constituent concepts was less than the AVE value. The squared values of all correlation coefficients were found to satisfy this criterion, confirming that overall discriminant validity was guaranteed. In addition, a correlation analysis between all variables used in this study was conducted to determine the direction of the hypothesis through the correlation of all variables. As a result of the analysis, the variables set out in the hypothesis were generally significantly correlated, and their direction was generally significant as well [82].

4.4. Hypotheses Test

The structural equation modelling technique was used to test the hypotheses set in the current study. Relative to the results of the analysis, a model with Δ2 = 1167.76, d.f. = 686, Δ2/d.f. = 1.702, RMR = 0.037, GFI = 0.0 = 809, IFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.911, CFI = 0.9222 was derived. This model can be described as appropriate because it is considered to be at an appropriate level when compared with the general evaluation indicators of the structural analysis of covariance. Table 4 shows the results of the path coefficient set in this study and the verification results of the research hypotheses.

Table 4.

Result of hypotheses test.

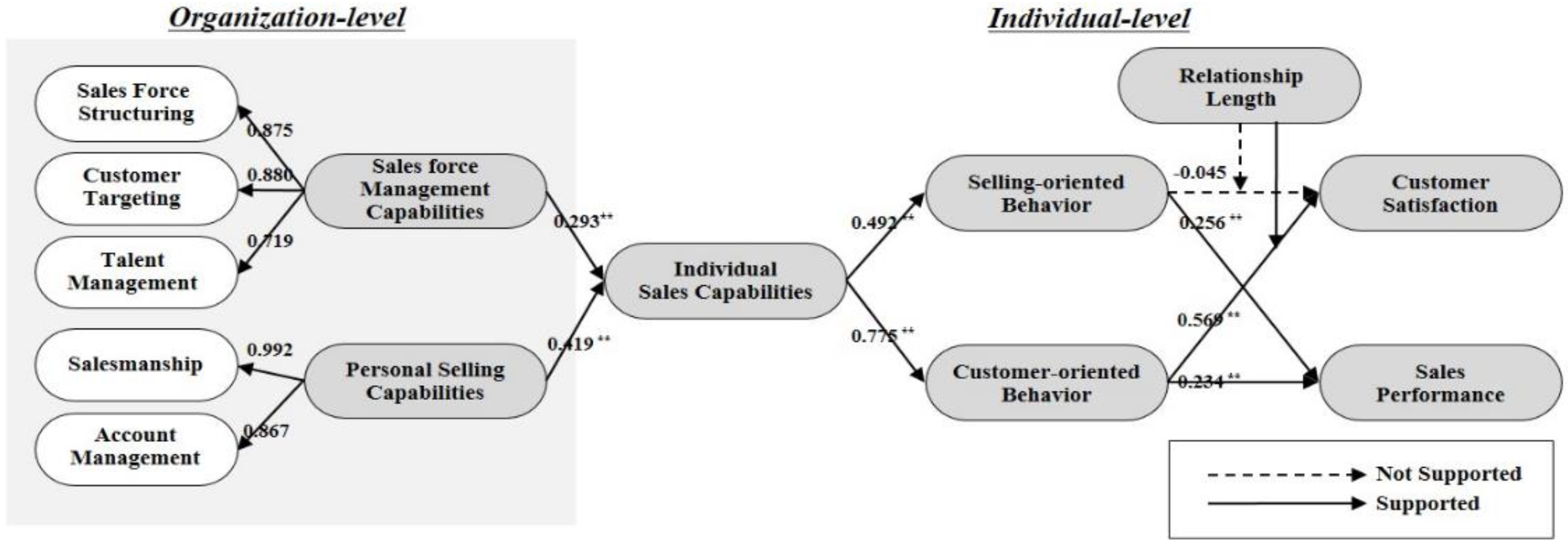

Since we hypothesized that the relationship length will have a moderating effect on the relationship between both sales-oriented sales behavior (SO) and customer-oriented sales behavior (CO) and customer satisfaction, the moderation effect was verified. In the relationship between selling-oriented sales behavior and customer satisfaction, the relationship length did not show a moderating effect (H6a), but it was found that the relationship length showed a moderating effect on the relationship between customer-oriented sales behavior and customer satisfaction (H6b). This is shown in Table 5. Also below is Figure 2 which represents the final structural model.

Table 5.

Results of moderating effect.

Figure 2.

Final structural model. ** p < 0.01.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Summary and Implications

This study commenced with the principal aim to examine the causal relationship between the organization’s sales-related variables, individual sales capabilities, sales-related behaviors (SOCO), and sales performance based on the resource-based theory. First, the effect of sales-related capability of the cosmetic door-to-door sales organization on the sales capability of door-to-door salespeople was examined. The discriminatory effect on satisfaction and sales performance was verified and, finally, the moderating effect of the relationship length on the relationship between SOCO and customer satisfaction was examined. The hypotheses test results for each research objective are as follows: First, in this study, business-related variables of the cosmetic door-to-door sales organization were divided into sales management capability and personal selling capability, and the effect of each organizational capability on the sales capability of the door-to-door salespeople was evaluated.

The result of the hypotheses test showed that both types of sales-related capabilities (salesforce management capabilities and personal selling capabilities) have significant positive effects on the individual sales capabilities (H1 and H2 are both supported). These findings lend credence to previous research [21], which posit that when the salesforce within the organization is well-organized, the salesforce will operate in an area with a balanced and acceptable workload and market potential, which enhances their selling capabilities. Similarly, these outcomes reinforce [22]’s position that the sales-related management capabilities of the organization enhance the ability of salespeople to do their job in real time, and handle customer issues capably.

Second, it was hypothesized that the individual sales capability of door-to-door salespeople would have a greater impact on customer-oriented sales behavior than on selling-oriented sales behavior, and this was also supported (H3 is supported). This outcome echoes [44]’s position that salespeople’s selling capabilities go a long way in influencing their selling behavior, especially those related to customers. The next hypothesis was that customer-oriented sales behavior will have a stronger positive (+) effect on customer satisfaction than selling-oriented sales behavior of door-to-door salespeople. Concerning this, the results showed that selling-oriented sales behavior has a negative (−) effect on customer satisfaction while customer-oriented sales behavior was partially supported as it was found to have a positive (+) effect (H4 is partially supported). Fourth, the hypothesis that customer-oriented sales behavior will have a stronger positive (+) effect on sales performance than selling-oriented behavior of door-to-door salespersons was supported (customer-oriented sales behavior has a positive effect on sales performance). However, selling-oriented sales behavior was partially supported as it was found to have no statistically significant effect (H5 is partially supported). This outcome lends support to [53], who contend that the effect of sales orientation on short-term performance is greater than that of long-term performance. Finally, as the relationship length increased, the causal relationship between customer-oriented sales behavior and customer satisfaction increased (H6b is supported). However, there was a direction between sales-oriented sales behavior and customer satisfaction, but there was no statistically significant negative (−) effect (H6a is not supported).

5.2. Theoretical & Academic Implications

This research advances theory by applying the resource-based theory to important marketing concepts—organizational and individual sales capabilities. The research modestly adds to established knowledge by presenting empirical proof from a salesforce capabilities point of view for this key theory with a research framework that demonstrates strong explanatory capacity. In addition, the existing sales literature reveals a lack of research that incorporates and analyzes the relationships between the concepts used in this analysis. In previous studies, the relationship between these constructs has been tested either in isolation or in different formats [43,83], which has led to the need for further empirical evaluation, validation, and theoretical advancement. This study further contributes to knowledge by presenting findings that assess several linkages between the constructs used, as well as using data from door-to-door cosmetics personal selling salespeople and customers.

The academic implications of this study are as follows: First, this is a study in the field of sales management that has not yet been studied in the field of marketing research. While the existing sales-related studies have focused on the individual capability of the salesperson, this study is focused on the sales capability of the organization and explains that these capabilities can be transferred. This result can trigger various follow-up studies on the connection between organization-level variables and individual variables in the field of personal selling or sales management. Second, while the existing sales management studies have verified the hypotheses based on the results of surveying salespeople, this study goes a step further and examines the results of door-to-door salespeople and customers of door-to-door salespeople, while applying quantitative performance data of door-to-door salespeople. Through this diversified approach, the possibility of generalization is increased, and a research methodology with high reliability and validity is proposed. This research methodology could engender new research with more sophisticated methodologies in the field of business management going forward.

5.3. Practical Implications

The results of this empirical analysis suggest the following practical implications: First of all, the fact that the organization’s sales-related capability affects the individual sales capability of door-to-door salespeople shows that the efforts of the organization to improve the capability of salespeople can eventually be transferred to individual capability. This suggests that there is a need for culture building or support within the organization. Second, the sales capability of door-to-door salespeople has a discriminatory effect on SOCO, and in particular, it has a greater impact on customer-oriented sales behavior than on sales-oriented behavior. This suggests that there is a need for activities to improve the understanding of the organization and its strategies. Thirdly, the fact that customer-oriented sales behavior has a positive effect on customer satisfaction and individual sales performance implies that customer-oriented sales behavior is higher than sales-oriented sales behavior of door-to-door salespersons. Furthermore, because it is profitable, it is necessary to induce sales from a customer perspective rather than a short-term sales maximization perspective. Further, sustainable behaviors have been described as a set of actions meant to protect natural, social, and human resources, and especially in the sales domain, the selling capability of both the company and the salespeople lead to engendering potentials in the latter, which are vital in creating and building sustainable business relationships with customers and other stakeholders. Lastly, the fact that the relationship length has a moderating effect on the relationship between customer-oriented sales behavior and customer satisfaction suggests that the longer the duration of the relationship with the customer in the cosmetic door-to-door sales channel, the greater the sales and satisfaction, underscoring the need to build and maintain long-term relationships with customers.

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

Despite these theoretical, academic, and practical implications, this study has the following limitations: First, because the cosmetics companies used in this study target door-to-door salespeople working in South Korea, the regional and cultural context can affect the organization’s sales capabilities, and this may limit generalization. Therefore, future research would need to increase the possibility of generalization by diversifying the companies used nationwide. Additionally, the authors used a sample of 151 respondents for this research, which is relatively small and, therefore, further research is needed to increase the possibility of generalization of the study results by increasing the sample size. Further, in order to measure customer performance, that is, customer satisfaction, a survey was conducted for only one customer per salesperson. However, there is a limit to explaining overall customer satisfaction through one customer. To examine this, we measured the customer satisfaction of one customer; but in future studies it is necessary to measure the overall satisfaction of the door-to-door salesperson. Lastly, in keeping with the research of [7], this study divided the organization’s sales-related capability into salesforce management capability and personal selling capability, but more diverse organizations can affect the sales capability of door-to-door salespeople. It is believed that there may be diverse capability and the organization’s sales-related capability may be classified in a wider variety. Therefore, it would be necessary to study more diverse organizational capabilities that affect sales capabilities at the individual level.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-T.Y. and F.E.A.; Formal analysis, H.-T.Y.; Funding acquisition, H.-T.Y.; Investigation, Y.-B.C.; Methodology, F.E.A.; Project administration, Y.-B.C.; Supervision, H.-T.Y.; Writing—original draft, Y.-B.C.; Writing—review & editing, F.E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A8044884).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to its classified nature.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A5A8044884).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koh, K.N. Scaling Femininity: Production of Semiotic Economy in the South Korean Cosmetics Industry. Signs Soc. 2020, 8, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Trade Insurance Corporation. Domestic and Foreign Cosmetics Industry Overview and Trend Analysis, KSURE Industry Trend Report; Korea Trade Insurance Corporation: Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Health Industry Promotion Agency. 2016 Cosmetic Industry Analysis Report. 2017. Available online: http://khiss.go.kr/mps (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Choedon, T.; Lee, Y.C. The effect of social media marketing activities on purchase intention with brand equity and social brand engagement: Empirical evidence from Korean cosmetic firms. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2020, 21, 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A.; Albaum, G.; Crittenden, V.L. Self-efficacy beliefs and direct selling sales performance. Int. J. Appl. Decis. Sci. 2020, 13, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoltners, A.A.; Sinha, P.; Lorimer, S.E. Sales force effectiveness: A framework for researchers and practitioners. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2008, 28, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenzi, P.; Sajtos, L.; Troilo, G. The dual mechanism of sales capabilities in influencing organizational performance. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3707–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohiomah, A.; Andreev, P.; Benyoucef, M.; Hood, D. The role of lead management systems in inside sales performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.; Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. The resource-based view of strategy: Origins, implications, and prospects. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 97–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, P.R. Toward a general theory of competitive rationality. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. The comparative advantage theory of competition. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wright, P.M. On Becoming a Strategic Partner: The Role of Human Resources in Gaining Competitive Advantage (CAHRS Working Paper# 97-09); Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sukaatmadja, I.; Yasa, N.; Rahyuda, H.; Setini, M.; Dharmanegara, I. Competitive advantage to enhance internationalization and marketing performance woodcraft industry: A perspective of resource-based view theory. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 6, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J. Expanding the resource-based view model of strategic human resource management. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 32, 331–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.; Aithal, P.S. A Resource-Based View and Institutional Theory-Based Analysis of Industry 4.0 Implementation in the Indian Engineering Industry. Int. J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. (IJMTS) 2020, 5, 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cron, W.L.; Baldauf, A.; Leigh, T.W.; Grossenbacher, S. The strategic role of the sales force: Perceptions of senior sales executives. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.C.; Plouffe, C.R. Assessing the evolution of sales knowledge: A 20-year content analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Matthes, J.M.; Friend, S.B. Interfacing and customer-facing: Sales and marketing selling centers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 77, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangaswamy, A.; Sinha, P.; Zoltners, A. An integrated model-based approach for sales force structuring. Mark. Sci. 1990, 9, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoltners, A.A.; Lorimer, S.E. Sales territory alignment: An overlooked productivity tool. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2000, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Darmon, R.Y. Leading the Sales Force: A Dynamic Management Process; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Hamel, G. Core capability concept. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 64, 70–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hope, J.; Hope, T. Competing in the Third Wave: The Ten Key Management Issues of the Information Age; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, M.W. Highflyers: Developing the Next Generation of Leaders; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, E.; Handfield-Jones, H.; Axelrod, B. The War for Talent; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, L.C.; Aoki, A.R.; Fernandes, T.S.; Lambert-Torres, G. Customer targeting optimization system for price-based demand response programs. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2019, 29, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnein, M.; Trautmann, H. Customer segmentation based on transactional data using stream clustering. In Pacific-Asia Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 280–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ballestar, M.T. Segmenting the Future of E-Commerce, One Step at a Time. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentz, J.O.; Shepherd, C.D.; Tashchian, A.; Dabholkar, P.A.; Ladd, R.T. A measure of selling skill: Scale development and validation. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2002, 22, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Auh, S.; Menguc, B. Knowledge sharing behaviors of industrial salespeople: An integration of economic, social psychological, and sociological perspectives. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 1333–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.T.; Amenuvor, F.E.; Yeo, C.K. Investigating Relationship between Control Mechanisms, Trust and Channel Outcome in Franchise System. J. Distrib. Sci. 2019, 17, 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cron, W.L.; Marshall, G.W.; Singh, J.; Spiro, R.L.; Sujan, H. Salesperson selection, training, and development: Trends, implications, and research opportunities. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2005, 25, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, R.E.; Dixon, A.L. Sellers and buyers on the boundary: Potential moderators of role stress-job outcome relationships. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, M.; Srivastava, P.; Iyer, K.N. An empirical model of salesperson competence, buyer-seller trust and collaboration: The moderating role of technological turbulence and product complexity. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2020, 28, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.R.; Matthews, L.M. Does Sleep Really Matter? Examining Sleep among Salespeople as Boundary Role Personnel for Key Job Factors. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2020, 27, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr.; Ford, N.M.; Walker, O.C., Jr. Measuring the job satisfaction of industrial salesmen. J. Mark. Res. 1974, 11, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.M. Strategic management and performance in public organizations: Findings from the Miles and Snow framework. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Owusu-Antwi, K.; Bae, S.C.; Shin, S.K.S.; Basilisco, R. Green Purchase Behavior: The Predictive Roles of Consumer Self-Determination, Perceived Customer Effectiveness and Perceived Price. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinsky, A.J.; Ingram, T.N. Correlates of salespeople’s ethical conflict: An exploratory investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 1984, 3, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, P.S.M. Competence at Work Models for Superior Performance; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hussain, B.; Hassan, H.; Synthia, I.J. Optimisation of knowledge sharing behaviour capability among sales executives: Application of SEM and fsQCA. Vine J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.P.; Martins, T.S. Sales capability and performance: Role of market orientation, personal and management capabilities. Rev. De Adm. Mackenzie 2020, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, R.E.; Marshall, G.W. Perspectives on selling and sales management education. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2002, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warech, M.A. Competency-based structured interviewing: At the Buckhead Beef Company. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G. Development of a Research Model to Analyze the Importance of NPD Capability and Sales Capability to Manage Innovation and to Improve Innovation Outcomes in SMEs: Irish Academy of Management Conference; Ulster University: Coleraine, Northern Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Oliver, R.L. Perspectives on behavior-based versus outcome-based salesforce control systems. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, D.W.; Ingram, T.N.; LaForge, R.W.; Young, C.E. Behavior-based and outcome-based salesforce control systems. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, R.; Weitz, B.A. The SOCO scale: A measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.E.; Le Bon, J.; Rapp, A. Gaining and leveraging customer-based competitive intelligence: The pivotal role of social capital and salesperson adaptive selling skills. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Bergami, M.; Marzocchi, G.L.; Morandin, G. Customer–organization relationships: Development and test of a theory of extended identities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Challagalla, G.N.; Shervani, T.A. Dimensions and types of supervisory control: Effects on salesperson performance and satisfaction. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, M.V.; Joshi, A.W. Motivating salesperson customer orientation: Insights from the job characteristics model. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr.; Ford, N.M.; Hartley, S.W.; Walker, O.C., Jr. The determinants of salesperson performance: A meta-analysis. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.W.; Kim, B.Y.; Oh, S.H. Core Self-Evaluation and Sales Performance of Female Salespeople in Face-to-Face Channel. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and performance: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1997, 8, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiro, R.L.; Weitz, B.A. Adaptive selling: Conceptualization, measurement, and nomological validity. J. Mark. Res. 1990, 27, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, D.K.; Reichheld, F.F.; Schefter, P. Avoid the four perils of CRM. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D.; Bitner, M.J. Relational benefits in services industries: The customer’s perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Owusu-Antwi, K.; Basilisco, R.; Seong-Chan, B. Customer Experience and behavioral intentions: The mediation role of customer perceived value. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 7, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Parvatiyar, A. The evolution of relationship marketing. Int. Bus. Rev. 1995, 4, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Relationship marketing of services—Growing interest, emerging perspectives. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S. Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Lemon, K.N.; Zeithaml, V.A. Return on marketing: Using customer equity to focus marketing strategy. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, S.B. The quest for competences: Competency studies can help you make HR decision, but the results are only as good as the study. Training 1996, 33, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Grigoriou, N.; Fuxman, L.; Reisel, W.D.; Hack-Polay, D.; Mohr, I. A generational study of employees’ customer orientation: A motivational viewpoint in pandemic time. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.E.; Sinkula, J.M. The complementary effects of market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation on profitability in small businesses. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2009, 47, 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujan, H.; Weitz, B.A.; Kumar, N. Learning orientation, working smart, and effective selling. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adusei, C.; Tweneboah-Koduah, I.; Agyapong, G.K. Sales-orientation and customer-orientation on performance of direct sales executives of fidelity bank, Ghana. Int. J. Financ. Bank. Stud. 2020, 9, 70–86. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Jung, Y.S. When does (mis) fit in customer orientation matter for frontline employees’ job satisfaction and performance? J. Mark. 2016, 80, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.E.; Beatty, S.E. Customer benefits and company consequences of customer-salesperson relationships in retailing. J. Retail. 1999, 75, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordhoff, C.S.; Kyriakopoulos, K.; Moorman, C.; Pauwels, P.; Dellaert, B.G. The bright side and dark side of embedded ties in business-to-business innovation. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S.P.; Venetis, K. Trust in industrial service relationships: Behavioural consequences, antecedents and the moderating effect of the duration of the relationship. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 636–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Webb, D.A. How functional, psychological, and social relationship benefits influence individual and firm commitment to the relationship. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2007, 22, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C. Understanding the effect of customer relationship management efforts on customer retention and customer share development. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.R.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.P.; Tripathi, A. Analysis and measurement of sales orientation-customer orientation (SOCO) of frontline sales executives with reference to BSNL (Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited) services in Western Uttar Pradesh (UP West Region). Int. J. Entrep. Dev. Stud. 2018, 5, 209–223. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).