How a Lack of Green in the Residential Environment Lowers the Life Satisfaction of City Dwellers and Increases Their Willingness to Relocate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Variables

2.3. Analysis Methods

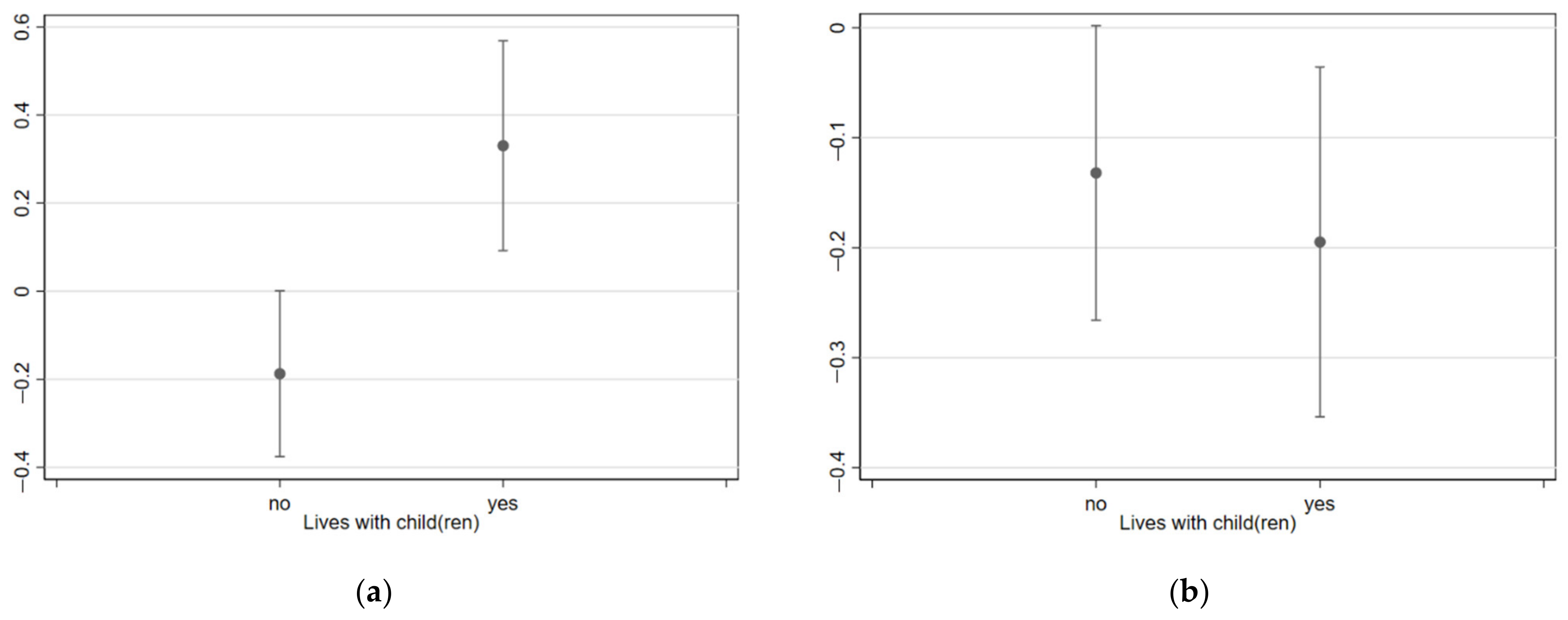

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of City Dwellers Who Are Considering vs. Not Considering Residential Relocation

3.2. Green Spaces in the Living Environment, Life Satisfaction and Considering Moving

3.3. Validation of the Results with Regard to Planning Moving

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; ISBN 0674045238. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.; Wilson, E. (Eds.) The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seresinhe, C.I.; Preis, T.; MacKerron, G.; Moat, H.S. Happiness is Greater in More Scenic Locations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrey, C.L.; Fleming, C.M. Valuing scenic amenity using life satisfaction data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and well-being: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.; Simons, R.; Losito, B.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia and the conservation ethic. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S., Wilson, E., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. Biophilia, biophobia, and natural landscapes. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S., Wilson, E., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 73–137. [Google Scholar]

- Korpela, K.; Hartig, T. Restorative Qualities of Favorite Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The Nature of the View from Home. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Black, A.M.; Fountaine, K.A.; Knotts, D.J. Reflection and attentional recovery as distinctive benefits of restorative environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sop Shin, W. The influence of forest view through a window on job satisfaction and job stress. Scand. J. Res. 2007, 22, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; de Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural Environments—Healthy Environments? An Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship between Greenspace and Health. Environ. Plan A 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C.; Rehdanz, K. The role of urban green space for human well-being. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krekel, C.; Kolbe, J.; Wüstemann, H. The greener, the happier? The effects of urban land use on residential well-being. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Wheeler, B.W.; Depledge, M.H. Would you be happier living in a greener urban area? A fixed-effects analysis of panel data. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, H.; Rüttenauer, T. How Selective Migration Shapes Environmental Inequality in Germany: Evidence from Micro-level Panel Data. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 94, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Lucas, R.; Smith, H. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Inglehart, R.; Tay, L. Theory and Validity of Life Satisfaction Scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. Using happiness data for envirionmental valuation: Issues and applications. J. Econ. Surv. 2009, 23, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Wakker, P.; Sarin, R. Back to Bentham? Explorations of Experienced Utility. Q. J. Econ. 1997, 112, 375–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kley, S. Explaining the Stages of Migration within a Life-course Framework. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 27, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, L.; Huinink, J.; Settersten, R.A. The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Adv. Life Course Res. 2019, 41, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, J. Behavioral aspects of the decision to migrate. Pap. Reg. Sci. Assoc. 1965, 15, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, G.; Fawcett, J. Motivations for Migration: An Assessment and a Value-Expectancy Research Model. In Migration Decision Making; Jong, G., de Gardner, R.W., Eds.; Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 13–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.; Mulder, C.H. Spatial Mobility, Family Dynamics, and Housing Transitions. Köln Z Soziol. 2015, 67, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.H. Migration Dynamics: A Life-Course Approach; Thesis Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kley, S. Facilitators and constraints at each stage of the migration decision process. Popul. Stud. 2017, 71, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulu, H.; Steele, F. Interrelationships between Childbearing and Housing Transitions in the Family Life Course. Demography 2013, 50, 1687–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulu, H. Fertility and Spatial Mobility in the Life Course: Evidence from Austria. Environ. Plan A 2008, 40, 632–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, A.; Catney, G. A Life Course Perspective on Urban-Rural Migration: The Importance of the Local Context. Popul. Space Place 2014, 20, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.H.; Wagner, M. The Connections between Family Formation and First-Time Home Ownership in the Context of West Germany and the Netherlands. Eur. J. Popul. Rev. Eur. Démogr. 2001, 17, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakdar, S.; Coulter, R.; Lersch, P.; Vidal, S. Family formation, parental background and young adults’ first entry into homeownership in Britain and Germany. Hous. Stud. 2018, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.H. Why Families Move; Russel Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Lauster, N.T. Housing and the Proper Performance of American Motherhood, 1940–2005. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, F.; Heins, S.; Elbersen, B.S. Lay discourses of the rural and stated and revealed preferences for rural living. Some evidence of the existence of a rural idyll in the Netherlands. J. Rural. Stud. 2002, 18, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grün, C.; Hauser, W.; Rhein, T. Is Any Job Better than No Job? Life Satisfaction and Re-employment. J. Labor Res. 2010, 31, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollmann-Schult, M. Parenthood and Life Satisfaction: Why Don’t Children Make People Happy? J. Marriage Fam. 2014, 76, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, J.; Klack, M.; Pätzold, A.; Wendler, D.; Möller, C. Das sind Deutschlands grünste Großstädte. Available online: https://interaktiv.morgenpost.de/gruenste-staedte-deutschlands/ (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Häder, S.; Häder, M.; Schmich, P. (Eds.) Telefonumfragen in Deutschland; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; ISBN 9783658239503. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, O.; Schnapp, K.-U. Hamburg-BUS 2016: Feldbericht. 2016. Available online: https://www.wiso.uni-hamburg.de/forschung/archiv/hhbus-files/feldbericht2016.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Kalter, F. Wohnortwechsel in Deutschland; Leske + Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Idler, E.; Benyamini, Y. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jylhä, M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisendörfer, P.; von Harder, B.; Diekmann, A. Umweltbewußtsein in Deutschland 1998: Ergebnisse einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsumfrage. Available online: https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/umweltbewusstseinsstudie_1998.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Environmental Consciousness in Germany. 2016. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12764 (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Kley, S. Migration im Lebensverlauf: Der Einfluss von Lebensbedingungen und Lebenslaufereignissen auf den Wohnortwechsel, 1st ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2009; ISBN 9783531167121. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, E.; Wachter, S. World Urbanization: The Critical Issue of the Twenty-First Century. In Global Urbanization; Birch, E., Wachter, S., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, B.A.; Coutts, A.M.; Livesley, S.J.; Harris, R.J.; Hunter, A.M.; Williams, N.S.G. Planning for cooler cities: A framework to prioritise green infrastructure to mitigate high temperatures in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan 2018, 134, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häder, S. Telefonstichproben. In Telefonumfragen in Deutschland; Häder, S., Häder, M., Schmich, P., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019; pp. 113–151. ISBN 9783658239503. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, W.; Thomas, D. The Child in America. Behavior Problems and Programs; Knopf: Oxford, MS, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

| Mean (Not Considering Moving) | Mean (Considering Moving) | Mean Total | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Considering moving | - | - | 0.226 | 0.418 | 0 | 1 |

| No green in the window view | 0.068 | 0.102 | 0.076 | 0.265 | 0 | 1 |

| Lack of green in residential area | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.214 | 0 | 1 |

| No balcony | 0.520 | 0.519 | 0.519 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| No green yard | 0.765 | 0.810 | 0.775 | 0.417 | 0 | 1 |

| No garden or terrace | 0.528 | 0.601 | 0.544 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 |

| Child(ren) and no garden/terrace | 0.126 | 0.206 | 0.144 | 0.351 | 0 | 1 |

| Hamburg vs. Cologne | 1.490 | 1.511 | 1.495 | 0.500 | 1 | 2 |

| Age | 54.595 | 50.181 | 53.597 | 15.786 | 18 | 96 |

| Female | 0.551 | 0.582 | 0.558 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| Migration background | 0.252 | 0.258 | 0.253 | 0.435 | 0 | 1 |

| Health | 5.781 | 5.457 | 5.708 | 1.315 | 1 | 7 |

| Part-time employed | 0.140 | 0.186 | 0.150 | 0.358 | 0 | 1 |

| Unemployed | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.024 | 0.152 | 0 | 1 |

| Enrolled in education | 0.029 | 0.056 | 0.035 | 0.185 | 0 | 1 |

| Retired | 0.278 | 0.218 | 0.265 | 0.441 | 0 | 1 |

| Other occupation | 0.061 | 0.065 | 0.062 | 0.242 | 0 | 1 |

| Employment status miss. | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.075 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income under 1000 EUR | 0.042 | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.217 | 0 | 1 |

| Income respondent miss. | 0.239 | 0.311 | 0.256 | 0.436 | 0 | 1 |

| Feeling of closeness to residential area | 5.794 | 5.218 | 5.664 | 1.371 | 1 | 7 |

| Homeownership | 0.483 | 0.359 | 0.455 | 0.498 | 0 | 1 |

| Lives with partner | 0.677 | 0.619 | 0.664 | 0.472 | 0 | 1 |

| Lives with child(ren) | 0.331 | 0.358 | 0.337 | 0.473 | 0 | 1 |

| Complete school/start studying | 0.039 | 0.100 | 0.053 | 0.224 | 0 | 1 |

| Job change self/partner | 0.122 | 0.266 | 0.155 | 0.362 | 0 | 1 |

| Marriage/cohabitation | 0.012 | 0.037 | 0.018 | 0.131 | 0 | 1 |

| Childbirth | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.024 | 0.152 | 0 | 1 |

| Life satisfaction | 6.035 | 5.555 | 5.926 | 0.935 | 1 | 7 |

| N = 989 | N = 897 | N = 1886 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. No green in the window view | 1 | ||||

| 2. Lack of green in residential area | 0.212 *** | 1 | |||

| 3. No garden or terrace | 0.192 *** | 0.078 *** | 1 | ||

| 4. No balcony | 0.068 ** | −0.015 | −0.387 *** | 1 | |

| 5. No green yard | −0.008 | −0.043 + | −0.238 *** | 0.128 *** | 1 |

| Model 1 1 Life Satisfaction | Model 2 2 Considering Moving | Model 3 3 Considering Moving | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marg. Effects | Robust Std. Err. | Marg. Effects | Robust Std. Err. | Marg. Effects | Robust Std. Err. | ||||

| No green in the window view | 0.095 | 0.074 | 0.043 | 0.031 | 0.222 | 0.113 | * | ||

| Lack of green in residential area | −0.048 | 0.089 | −0.025 | 0.039 | −0.138 | 0.149 | |||

| No balcony | −0.101 | 0.048 | * | 0.011 | 0.019 | −0.013 | 0.070 | ||

| No green yard | −0.053 | 0.051 | 0.060 | 0.021 | ** | 0.170 | 0.078 | * | |

| No garden or terrace | −0.132 | 0.068 | + | −0.029 | 0.027 | −0.187 | 0.096 | + | |

| Child(ren) and no garden/terrace | −0.063 | 0.091 | 0.153 | 0.037 | *** | 0.518 | 0.135 | *** | |

| Hamburg vs. Cologne | 0.010 | 0.043 | −0.016 | 0.017 | −0.056 | 0.064 | |||

| Age | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.001 | + | −0.003 | 0.002 | ||

| Gender | 0.016 | 0.046 | 0.019 | 0.018 | 0.073 | 0.065 | |||

| Migration background | 0.015 | 0.048 | −0.011 | 0.020 | −0.045 | 0.074 | |||

| Household income under 1000 EUR | 0.007 | 0.130 | 0.047 | 0.050 | 0.153 | 0.179 | |||

| Income respondent miss. | −0.070 | 0.050 | 0.079 | 0.020 | *** | 0.235 | 0.076 | ** | |

| Homeownership | 0.056 | 0.051 | −0.054 | 0.020 | ** | −0.169 | 0.076 | * | |

| Lives with partner | 0.279 | 0.054 | *** | −0.008 | 0.020 | 0.128 | 0.076 | + | |

| Lives with child(ren) | −0.008 | 0.069 | 0.101 | 0.028 | *** | 0.354 | 0.100 | *** | |

| Complete school/start studying | 0.181 | 0.093 | + | 0.075 | 0.047 | 0.359 | 0.166 | * | |

| Job change self/partner | −0.076 | 0.061 | 0.131 | 0.024 | *** | 0.422 | 0.096 | *** | |

| Marriage/cohabitation | 0.146 | 0.114 | 0.157 | 0.066 | * | 0.674 | 0.246 | ** | |

| Childbirth | 0.423 | 0.118 | *** | −0.055 | 0.060 | 0.033 | 0.212 | ||

| Health | 0.211 | 0.022 | *** | −0.026 | 0.007 | *** | |||

| Feeling of closeness to residential area | 0.181 | 0.018 | *** | −0.039 | 0.007 | *** | |||

| Part-time employed | −0.250 | 0.069 | *** | 0.050 | 0.027 | + | |||

| Unemployed | −0.221 | 0.134 | + | −0.056 | 0.059 | ||||

| Enrolled in education | −0.271 | 0.143 | + | 0.007 | 0.067 | ||||

| Retired | 0.058 | 0.075 | 0.029 | 0.029 | |||||

| Other occupation | −0.275 | 0.093 | ** | 0.026 | 0.038 | ||||

| Employment status miss. | 0.782 | 0.318 | * | −0.043 | 0.136 | ||||

| Life satisfaction | −0.576 | 0.070 | *** | ||||||

| Number of cases | 1886 | 1886 | 1886 | ||||||

| Degrees of freedom | 27 | 27 | 20 | ||||||

| McFadden’s pseudo R2 | 0.093 | ||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.248 | ||||||||

| Overall model significance | *** | *** | *** | ||||||

| Model 3 1 Considering Moving | Model 4 2 Planning Moving | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marg. Effects | Robust Std. Err. | Marg. Effects | Robust Std. Err. | |||

| No green in the window view | 0.222 | 0.113 | * | 0.420 | 0.139 | ** |

| Lack of green in residential area | −0.138 | 0.149 | −0.234 | 0.206 | ||

| No balcony | −0.013 | 0.070 | −0.110 | 0.094 | ||

| No green yard | 0.170 | 0.078 | * | 0.234 | 0.111 | * |

| No garden or terrace | −0.187 | 0.096 | + | −0.344 | 0.127 | ** |

| Child(ren) and no garden/terrace | 0.518 | 0.135 | *** | 0.408 | 0.185 | * |

| Hamburg vs. Cologne | −0.056 | 0.064 | −0.203 | 0.088 | * | |

| Age | −0.003 | 0.002 | −0.017 | 0.003 | *** | |

| Gender | 0.073 | 0.065 | 0.007 | 0.090 | ||

| Migration background | −0.045 | 0.074 | 0.132 | 0.096 | ||

| Household income under 1000 EUR | 0.153 | 0.179 | 0.271 | 0.202 | ||

| Income respondent miss. | 0.235 | 0.076 | ** | 0.137 | 0.101 | |

| Homeownership | −0.169 | 0.076 | * | −0.268 | 0.112 | * |

| Lives with partner | 0.128 | 0.076 | + | 0.000 | 0.101 | |

| Lives with child(ren) | 0.354 | 0.100 | *** | 0.056 | 0.125 | |

| Complete school/start studying | 0.359 | 0.166 | * | 0.376 | 0.171 | * |

| Job change self/partner | 0.422 | 0.096 | *** | 0.335 | 0.107 | ** |

| Marriage/cohabitation | 0.674 | 0.246 | ** | 0.806 | 0.224 | *** |

| Childbirth | 0.033 | 0.212 | 0.346 | 0.227 | ||

| Life satisfaction | −0.576 | 0.070 | *** | −0.491 | 0.087 | *** |

| Number of cases | 1886 | 1886 | ||||

| Degrees of freedom | 20 | 20 | ||||

| Wald χ2 | 201.2 | 211.0 | ||||

| Wald χ2 of exogeneity | 17.9 | *** | 10.6 | ** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kley, S.; Dovbishchuk, T. How a Lack of Green in the Residential Environment Lowers the Life Satisfaction of City Dwellers and Increases Their Willingness to Relocate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073984

Kley S, Dovbishchuk T. How a Lack of Green in the Residential Environment Lowers the Life Satisfaction of City Dwellers and Increases Their Willingness to Relocate. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073984

Chicago/Turabian StyleKley, Stefanie, and Tetiana Dovbishchuk. 2021. "How a Lack of Green in the Residential Environment Lowers the Life Satisfaction of City Dwellers and Increases Their Willingness to Relocate" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073984

APA StyleKley, S., & Dovbishchuk, T. (2021). How a Lack of Green in the Residential Environment Lowers the Life Satisfaction of City Dwellers and Increases Their Willingness to Relocate. Sustainability, 13(7), 3984. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073984