Environmental, Social and Governance Performance of Chinese Multinationals: A Comparison of State- and Non-State-Owned Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Legitimacy Perspective

2.2. Stakeholder Theory

3. Literature and Hypothesis

3.1. Internationalization and Corporate ESG Performance

3.2. ESG Performance of Chinese SOEs and Non-SOEs in the International Markets

4. Methodology

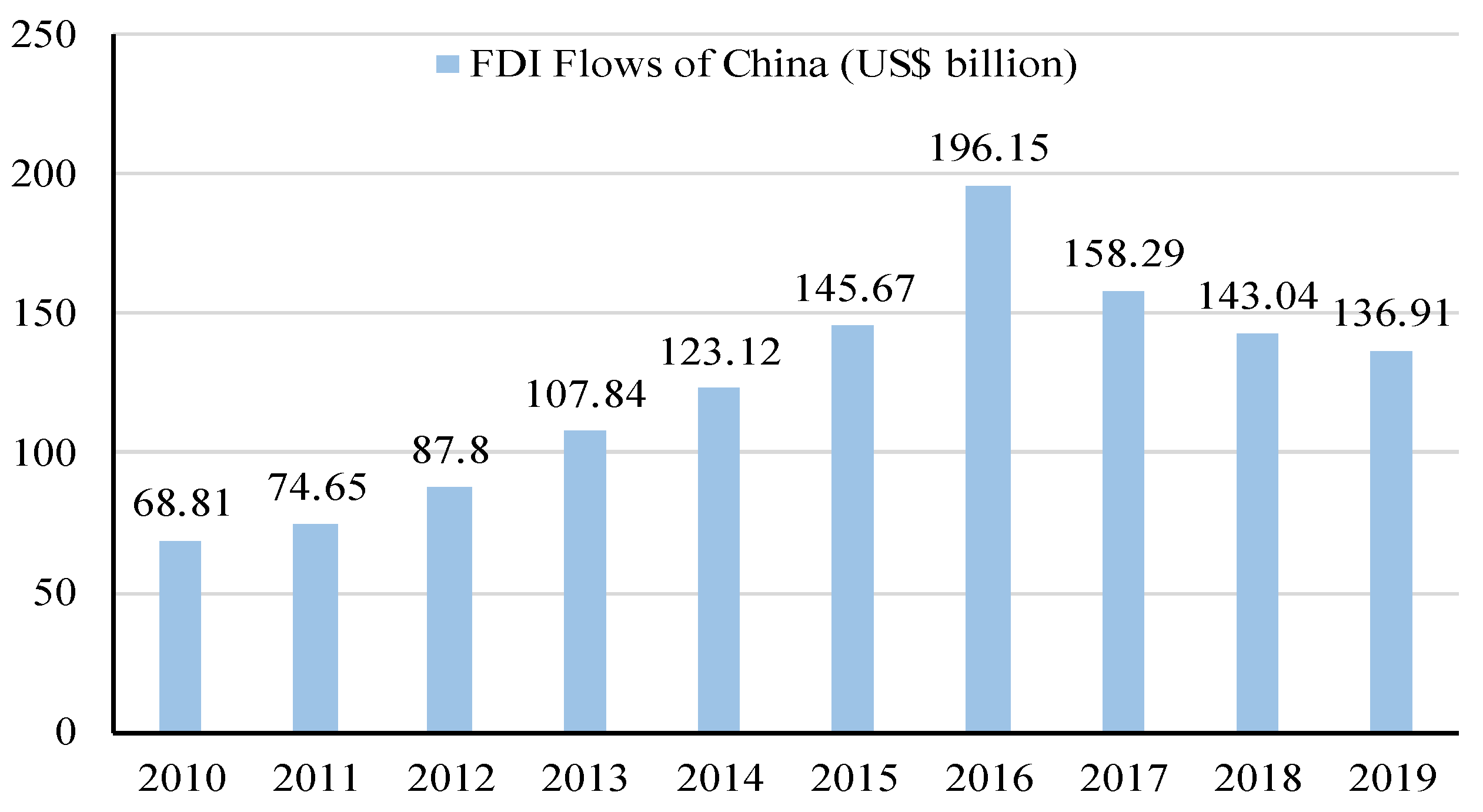

4.1. Sample and Data

4.2. Variables Measurement

4.2.1. Dependent Variable—ESG Performance

4.2.2. Independent Variable—Internationalization

4.2.3. Control Variables

4.3. Empirical Models

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Results

5.2. Regression Results

5.3. Robustness and Endogeneity

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Env_P | 1 | |||||||||||

| (2) Soc_P | 0.127 * | 1 | ||||||||||

| (3) Gov_P | 0.753 * | 0.299 * | 1 | |||||||||

| (4) Int_Sub | 0.075 * | 0.045 * | 0.102 * | 1 | ||||||||

| (5) SOE | 0.224 * | 0.106 * | 0.136 * | 0.071 * | 1 | |||||||

| (6) Size | 0.275 * | 0.172 * | 0.281 * | 0.288 * | 0.361 * | 1 | ||||||

| (7) Age | −0.047 * | 0.077 * | −0.043 * | 0.078 * | 0.193 * | 0.111 * | 1 | |||||

| (8) Lev | 0.168 * | 0.035 * | −0.041 * | 0.204 * | 0.360 * | 0.454 * | 0.188 * | 1 | ||||

| (9) Growth | −0.024 | 0.046 * | 0.072 * | 0.043 * | −0.093 * | −0.029 | −0.035 * | −0.001 | 1 | |||

| (10) Cashflows | 0.053 * | 0.077 * | 0.246 * | −0.012 | −0.025 | 0.150 * | 0.008 | −0.154 * | −0.017 | 1 | ||

| (11) ROE | 0.076 * | 0.254 * | 0.525 * | 0.043 * | −0.035 * | 0.144 * | −0.003 | −0.133 * | 0.254 * | 0.317 * | 1 | |

| (12) MTB | −0.02 | −0.056 * | −0.055 * | −0.016 | −0.034 * | −0.122 * | −0.039 * | 0.246 * | 0.108 * | 0.018 | 0.046 * | 1 |

References

- Godos-Díez, J.-L.; Cabeza-García, L.; Fernández-González, C. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Internationalisation Strategies: A Descriptive Study in the Spanish Context. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Ambos, T.C.; Eggers, F.; Cesinger, B. Distance and perceptions of risk in internationalization decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, G.R.G.; Rygh, A.; Lunnan, R. The Benefits of Internationalization for State-Owned Enterprises. Glob. Strat. J. 2016, 6, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Wang, C.; Kafouros, M. The Role of the State in Explaining the Internationalization of Emerging Market Enterprises. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, S.; Nielsen, B.B.; Nielsen, S. Emerging Market Multinational Companies and Internationalization: The Role of Home Country Urbanization. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 23, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, M.J.; Delmas, M. Voluntary Agreements to Improve Environmental Quality: Symbolic and Substantive Cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-L.; Kung, F.-H. Drivers of Environmental Disclosure and Stakeholder Expectation: Evidence from Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Li, C. State ownership and internationalization: The advantage and disadvantage of stateness. J. World Bus. 2021, 56, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.-L.; Kong, D.; Tan, W.; Wang, W. Being Good When Being International in an Emerging Economy: The Case of China. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 130, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. Internationalization and performance: The role of state ownership. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 25, 1130–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J. China and the Emerging Markets. Capital Wars; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Alon, I.; Anderson, J.; Munim, Z.H.; Ho, A. A review of the internationalization of Chinese enterprises. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2018, 35, 573–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, G.; Hart, S.; Yeung, B. Do Corporate Global Environmental Standards Create or Destroy Market Value? Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 1059–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, P. Multinational Companies and the Natural Environment: Determinants of Global Environmental Policy. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 747–760. [Google Scholar]

- Attig, N.; Boubakri, N.; El Ghoul, S.; Guedhami, O. Firm Internationalization and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 134, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-B. Multinationals and sustainable development: Does internationalization develop corporate sustainability of emerging market multinationals? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeou, P.C.; Zyglidopoulos, S.; Williamson, P. Internationalization as a driver of the corporate social performance of extractive industry firms. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Tashman, P.; Kostova, T. Escaping the iron cage: Liabilities of origin and CSR reporting of emerging market multinational enterprises. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2017, 48, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.J.; Pavelin, S.; Porter, L.A. Corporate social performance and geographical diversification. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.J.; Pavelin, S.; Porter, L.A. Corporate Charitable Giving, Multinational Companies and Countries of Concern. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Ong, C.-F.; Hsu, S.-C. The linkages between internationalization and environmental strategies of multinational construction firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 116, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, Y.-L.; Jiang, K.; Mak, B.S.C.; Tan, W. Corporate Social Performance, Firm Valuation, and Industrial Difference: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Bolaños, E.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E.; Delgado-Márquez, B.L. Disentangling the influence of internationalization on sustainability development: Evidence from the energy sector. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Arregle, J.-L.; Hitt, M.A.; Spadafora, E.; Van Essen, M. Home Country Institutions and the Internationalization-Performance Relationship. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1075–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanis, R.; Richardson, G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Tax Aggressiveness: A Test of Legitimacy Theory. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2012, 31, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.; Maroun, W. Corporate social responsibility reporting by South African mining companies: Evidence of legitimacy theory. South. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 48, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Communicating CSR practices-Role of internationalization of emerging market firms. J. Mark. Commun. 2019, 25, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, K.; Schlick, C. The relationship between sustainability performance and sustainability disclosure-Reconciling voluntary disclosure theory and legitimacy theory. J. Account. Public Policy 2016, 35, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilling, M.V. Some thoughts on legitimacy theory in social and environmental accounting. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2004, 24, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Cuganesan, S.; Ward, L. Legitimacy Theory: A Story of Reporting Social and Environmental Matters within the Australian Food and Beverage Industry. In Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Conference, Auckland, Australia, 5–8 July 2007; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Albasu, J.; Nyameh, J. Relevance of Stakeholders Theory, Organizational Identity Theory and Social Exchange Theory to Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees Performance in the Commercial Banks in Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 4, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, P. Make Your Suppliers Greater Stakeholders within Your Purchasing Operation. 2020. Available online: https://commons.erau.edu/publication/1452 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Ferrell, O. Business ethics and customer stakeholders. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, T.; Waterman, H. Research of Excellence; Harper&Row Publ.: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, R.; Margula, S.; Martinuzzi, A. Public Policies on CSR in Europe: Themes, Instruments, and Regional Differences. Universität für Bodenkultur: Wien, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hörisch, J.; Burritt, R.L.; Christ, K.L.; Schaltegger, S. Legal systems, internationalization and corporate sustainability. An empirical analysis of the influence of national and international authorities. Corp. Governance Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 17, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N. Building Norms from the Grassroots Up: Divestment, Expressive Politics, and Climate Change. Law Policy 2017, 39, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.E.; Mudambi, R.; Narula, R. Multinational Enterprises and Local Contexts: The Opportunities and Challenges of Multiple Embeddedness. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, V.; Kostova, T. Unpacking the Institutional Complexity in Adoption of CSR Practices in Multinational Enterprises. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strike, V.M.; Gao, J.; Bansal, P. Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2006, 37, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Perales, I.; Garces-Ayerbe, C.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Suarez-Galvez, C. Is Strategic Proactivity a Driver of an Environmental Strategy? Effects of Innovation and Internationalization Leadership. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, J.; Vachon, S. Linking Environmental Management to Environmental Performance: The Interactive Role of Industry Context. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchicci, L.; Dowell, G.; King, A.A. Environmental Capabilities and Corporate Strategy: Exploring Acquisitions among US Manufacturing Firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1053–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestre, L.; Rajagopalan, N.; Dutta, S. Constraints in acquiring and utilizing directors’ experience: An empirical study of new-market entry in the pharmaceutical industry. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennelly, J.J.; Lewis, E. Degree of Internationalization and Environmental Performance: Evidence from U.S. Multinationals. Multidiscip. Insights New AIB Fellows 2004, 9, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, W.M.G.; Carpenter, M.A. Internationalization and Firm Governance: The Roles of CEO Compensation, Top Team Composition, and Board Structure. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Detomasi, D.A. The Multinational Corporation and Global Governance: Modelling Global Public Policy Networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 71, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacperczyk, A. With greater power comes greater responsibility? takeover protection and corporate attention to stakeholders. Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. The relationship between corporate diversification and corporate social performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2012, 34, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, S.J.; Soyka, P.A.; Ameer, P.G. Does Improving a Firm’s Environmental Management System and Environmental Performance Result in a Higher Stock Price? J. Investig. 1997, 6, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Garvis, D.M. International Corporate Entrepreneurship and Firm Performance: The Moderating Effect of International Environmental Hostility. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, K.H.; Kim, B. Internationalization and corporate social responsibility in the restaurant industry: Risk perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1105–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.; Henderson, V. Effects of Air Quality Regulations on Polluting Industries. J. Political Econ. 2000, 108, 379–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyglidopoulos, S.C. The Social and Environmental Responsibilities of Multinationals: Evidence from the Brent Spar Case. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 36, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T.R. Corporate Social Responsibility, Public Policy, and NGO Activism in Europe and the United States: An Institutional-Stakeholder Perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliyanto, A.; Marciano, D. Interdependency between internationalization, firm performance, and corporate governance. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2018), Chonburi, Thailand, 1 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, M.; Ribeiro, M.D.C.A. Internationalization strategies in Portuguese Higher Education Institutions-time to move on and to move beyond. LSP in Multi-disciplinary contexts of Teaching and Research. Pap. 16th Int. AELFE Conf. 2018, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, S.A.; Badir, Y. Convergence of corporate governance in Malaysia and Thailand. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2014, 4, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cui, L. Can Strong Home Country Institutions Foster the Internationalization of MNEs? Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felício, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Samagaio, A. Corporate Governance and the Performance of Commercial Banks: A Fuzzy-Set QCA Approach. J. Small Bus. Strateg. 2016, 26, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, S.; Mensching, H.; Calabrò, A.; Cheng, C.-F.; Filser, M. Family firm internationalization: A configurational approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5473–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugasundaram, S. Internationalization and governance of Indian family-owned business groups. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Garde Sánchez, R.; López Hernández, A.M. Managers as Drivers of CSR in State-Owned Enterprises. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 777–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Pachón, J.-R.; Garde-Sánchez, R.; Rodríguez-Bolívar, M.-P. A Systemic View of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Knowl. Process. Manag. 2014, 21, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ntim, C.G.; Ullah, F. The brighter side of being socially responsible: CSR ratings and financial distress among Chinese state and non-state owned firms. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2018, 26, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L. State-Owned Enterprises: CSR Solution or Just Another Bump in the Road. Manag. Commun. Q. 2011, 25, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Lai, K.-H. Corporate social responsibility practices and performance improvement among Chinese national state-owned enterprises. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Zhang, J.; Usman, M.; Badulescu, A.; Sial, M.S. Ownership Reduction in State-Owned Enterprises and Corporate Social Responsibility: Perspective from Secondary Privatization in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, F. State-Owned Shareholding and CSR: Do Multiple Financing Methods Matter?-Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Jamali, D. Institutional complexity of host country and corporate social responsibility: Developing vs developed countries. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, B.; Yeung, M.; Laforet, S. China’s outward foreign direct investment: Location choice and firm ownership. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.W. Outside directors and firm performance during institutional transitions. Strat. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Qian, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in China: Symbol or Substance? Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, Y.; Ntim, C.G.; Chen, Y.; Ullah, F.; Li, H.-X.; Ye, Z. CEO Attributes, Sustainable Performance, Environmental Performance, and Environmental Reporting: New Insights from Upper Echelons Perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zeng, S.; Chen, H. Signaling good by doing good: How does environmental corporate social responsibility affect international expansion? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 946–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Lu, Y.; Liang, Q. Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A Corporate Governance Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, J.; Shapiro, D.; Lin, Z. Institutional compatibility and the internationalization of Chinese SOEs: The moderating role of home subnational institutions. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-Y. Top management team characteristics and firm internationalization: The moderating role of the size of middle managers. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Saleh, A. The effect of CSR commitment on firms’ level of internationalization. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 1415–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. The role of corporate sustainability performance for economic performance: A firm-level analysis of moderation effects. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, S.; Wang, L. The Long-Term Sustenance of Sustainability Practices in MNCs: A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective of the Role of R&D and Internationalization. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. Panel Data Models. In A Companion to Theoretical Econometrics; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Malden, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 349–365. ISBN 978-0-470-99624-9. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, E.M.; Prakash, R.; Vera-Muñoz, S.C. Firm-Value Effects of Carbon Emissions and Carbon Disclosures. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 695–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Scores and Financial Performance of Multilatinas: Moderating Effects of Geographic International Diversification and Financial Slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Zaefarian, G.; Ullah, F. How to use instrumental variables in addressing endogeneity? A step-by-step procedure for non-specialists. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.A.B.C.; Bergmann, D.R.; Castro, F.H.; da Silveira, A.D.M. Endogeneidade Em Regressões Com Dados Em Painel: Um Guia Metodológico Para Pesquisa Em Finanças Corporativas. Rev. Bras. Gestão Negócios 2020, 22, 437–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hoi, C.K.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, H. Is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Associated with Tax Avoidance? Evidence from Irresponsible CSR Activities. Account. Rev. 2013, 88, 2025–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, N.T.M.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Tu, C.A.; Yoshino, N.; Kim, C.J. Performance Differential between Private and State-owned Enterprises: An Analysis of Profitability and Solvency. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amighini, A.A.; Rabellotti, R.; Sanfilippo, M. Do Chinese state-owned and private enterprises differ in their internationalization strategies? China Econ. Rev. 2013, 27, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Internationalization | Int_Sub | the number of subsidiaries each parent firm owns. |

| Environmental Performance | Env_P | the reported data taking into account the resource use, emissions, and innovation for environmental concerns. |

| Social Performance | Soc_P | the reported data taking into account the human rights, workforce, community, and product responsibility. |

| Governance Performance | Gov_P | the reported data taking into account the management, shareholders, and CSR strategy. |

| SOE | SOE | the dummy variable which is equals “1” if the majority of the shares of the company are owned by the government or government-affiliated institutions or agencies and “0” otherwise. |

| Size | Size | the natural logarithm of the number of employees. |

| Leverage | Lev | the ratio of total liabilities to total assets at the end of the year. |

| Age | Age | the value obtained by the subtraction of the current year from the year of the company’s establishment. |

| Growth | Growth | the change in business income scaled by business income in t−1. |

| Cashflows | Cash | the operating cashflow divided by the total assets. |

| ROE | ROE | the ratio of net profit to total shareholders’ equity. |

| Market to book ratio | MTB | the market value of equity divided by the book value of equity |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Env_P | 6234 | 2.061 | 5.535 | 0.000 | 23.000 |

| Soc_P | 6234 | 4.131 | 3.659 | −6.870 | 15.000 |

| Gov_P | 6234 | 6.413 | 3.592 | −0.433 | 17.007 |

| Int_Sub | 6234 | 4.348 | 5.746 | 1.000 | 37.000 |

| SOE | 6234 | 0.291 | 0.454 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Size | 6234 | 8.053 | 1.228 | 5.464 | 11.387 |

| Lev | 6234 | 0.434 | 0.198 | 0.061 | 0.868 |

| Age | 6234 | 16.090 | 5.756 | 2.000 | 51.000 |

| Growth | 6234 | 0.204 | 0.351 | −0.399 | 2.079 |

| Cashflows | 6234 | 0.044 | 0.062 | −0.130 | 0.215 |

| ROE | 6234 | 0.073 | 0.107 | −0.470 | 0.345 |

| MTB | 6234 | 4.473 | 2.592 | 1.400 | 16.022 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Env_P | Soc_P | Gov_P | |

| Int_Sub | 0.0399 *** | −0.0103 | 0.0390 *** |

| (0.0134) | (0.0084) | (0.0074) | |

| Size | 0.906 *** | 0.499 *** | 0.653 *** |

| (0.0752) | (0.0476) | (0.0400) | |

| Lev | 1.942 *** | −0.823 *** | −1.795 *** |

| (0.4400) | (0.2960) | (0.2460) | |

| Age | 0.0401 *** | 0.0413 *** | 0.0182 *** |

| (0.0118) | (0.0082) | (0.0066) | |

| Growth | −0.2200 | 0.1210 | −0.227 ** |

| (0.1650) | (0.1370) | (0.0948) | |

| Cashflows | 2.066 * | (0.8920) | 3.492 *** |

| (1.1140) | (0.7530) | (0.6480) | |

| ROE | 2.050 *** | 7.413 *** | 15.32 *** |

| (0.6620) | (0.4170) | (0.4320) | |

| MTB | −0.0700 ** | −0.0420 ** | −0.0423 ** |

| (0.0275) | (0.0205) | (0.0175) | |

| Constant | −10.60 *** | 0.5440 | −1.887 *** |

| (0.6760) | (0.8440) | (0.4470) | |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 6234 | 6234 | 6234 |

| R-squared | 0.230 | 0.191 | 0.417 |

| Variables | SOE | Non-SOE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Env_P | Soc_P | Gov_P | Env_P | Soc_P | Gov_P | |

| Int_Sub | 0.0417 ** | 0.0170 | 0.0529 *** | 0.0513 *** | −0.0244 ** | 0.0381 *** |

| (0.0210) | (0.0141) | (0.0117) | (0.0169) | (0.0106) | (0.0093) | |

| Size | 0.978 *** | 0.732 *** | 0.785 *** | 0.693 *** | 0.350 *** | 0.484 *** |

| (0.1420) | (0.0856) | (0.0727) | (0.0872) | (0.0597) | (0.0483) | |

| Lev | −1.1520 | −1.290 ** | −3.877 *** | 1.969 *** | −0.729 ** | −1.660 *** |

| (1.0380) | (0.5890) | (0.5520) | (0.4540) | (0.3520) | (0.2640) | |

| Age | 0.0177 | 0.0397 ** | 0.0077 | 0.0406 *** | 0.0375 *** | 0.0194 *** |

| (0.0297) | (0.0157) | (0.0156) | (0.0113) | (0.0099) | (0.0069) | |

| Growth | −0.1830 | 0.545 * | 0.0214 | −0.1010 | −0.0573 | −0.236 ** |

| (0.3850) | (0.2900) | (0.2140) | (0.1710) | (0.1530) | (0.1010) | |

| Cashflows | 1.9830 | −1.7510 | 3.055 ** | 1.989 * | −0.4800 | 3.563 *** |

| (2.6800) | (1.4960) | (1.4670) | (1.0830) | (0.8650) | (0.6880) | |

| ROE | 1.4860 | 6.667 *** | 14.18 *** | 2.453 *** | 7.726 *** | 15.99 *** |

| (1.5660) | (0.7750) | (0.8950) | (0.5790) | (0.4910) | (0.4640) | |

| MTB | −0.1100 | 0.0074 | −0.0274 | −0.0441 | −0.0557 ** | −0.0338 * |

| (0.0712) | (0.0414) | (0.0428) | (0.0278) | (0.0244) | (0.0182) | |

| Constant | −7.565 *** | 0.7020 | −0.0595 | −8.922 *** | 1.2740 | −0.869 ** |

| (1.4550) | (1.7230) | (1.3690) | (0.7270) | (0.9410) | (0.4150) | |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1814 | 1814 | 1814 | 4420 | 4420 | 4420 |

| R-squared | 0.321 | 0.254 | 0.442 | 0.16 | 0.172 | 0.439 |

| Variables | GMM | 2sls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Env_P | Soc_P | Gov_P | Env_P | Soc_P | Gov_P | |

| Int_Sub | 0.0606 *** | −0.0052 | 0.0471 *** | 0.0606 *** | −0.0052 | 0.0471 *** |

| (0.0167) | (0.0101) | (0.0091) | (0.0167) | (0.0101) | (0.0091) | |

| Size | 0.827 *** | 0.520 *** | 0.666 *** | 0.827 *** | 0.520 *** | 0.666 *** |

| (0.0861) | (0.0567) | (0.0468) | (0.0861) | (0.0567) | (0.0468) | |

| Lev | 1.615 *** | −1.001 *** | −1.825 *** | 1.615 *** | −1.001 *** | −1.825 *** |

| (0.5090) | (0.3580) | (0.2940) | (0.5090) | (0.3580) | (0.2940) | |

| Age | 0.0448 *** | 0.0377 *** | 0.0223 *** | 0.0448 *** | 0.0377 *** | 0.0223 *** |

| (0.0140) | (0.0097) | (0.0079) | (0.0140) | (0.0097) | (0.0079) | |

| Growth | −0.2020 | 0.0101 | −0.1610 | −0.2020 | 0.0101 | −0.1610 |

| (0.2280) | (0.1760) | (0.1290) | (0.2280) | (0.1760) | (0.1290) | |

| Cashflows | 1.4690 | −1.1770 | 3.527 *** | 1.4690 | −1.1770 | 3.527 *** |

| (1.3690) | (0.9040) | (0.7930) | (1.3690) | (0.9040) | (0.7930) | |

| ROE | 1.422 * | 7.369 *** | 14.73 *** | 1.422 * | 7.369 *** | 14.73 *** |

| (0.7530) | (0.4580) | (0.4860) | (0.7530) | (0.4580) | (0.4860) | |

| MTB | −0.0971 *** | −0.0323 | −0.0560 *** | −0.0971 *** | −0.0323 | −0.0560 *** |

| (0.0343) | (0.0243) | (0.0216) | (0.0343) | (0.0243) | (0.0216) | |

| Constant | −10.38 *** | 0.5360 | −2.631 *** | −10.38 *** | 0.5360 | −2.631 *** |

| (0.8110) | (1.1140) | (0.4760) | (0.8110) | (1.1140) | (0.4760) | |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 4537 | 4537 | 4537 | 4537 | 4537 | 4537 |

| R-squared | 0.248 | 0.195 | 0.436 | 0.248 | 0.195 | 0.436 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khalid, F.; Sun, J.; Huang, G.; Su, C.-Y. Environmental, Social and Governance Performance of Chinese Multinationals: A Comparison of State- and Non-State-Owned Enterprises. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074020

Khalid F, Sun J, Huang G, Su C-Y. Environmental, Social and Governance Performance of Chinese Multinationals: A Comparison of State- and Non-State-Owned Enterprises. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074020

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhalid, Fahad, Juncheng Sun, Guanhua Huang, and Chih-Yi Su. 2021. "Environmental, Social and Governance Performance of Chinese Multinationals: A Comparison of State- and Non-State-Owned Enterprises" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074020

APA StyleKhalid, F., Sun, J., Huang, G., & Su, C.-Y. (2021). Environmental, Social and Governance Performance of Chinese Multinationals: A Comparison of State- and Non-State-Owned Enterprises. Sustainability, 13(7), 4020. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074020