Taking Lead for Sustainability: Environmental Managers as Institutional Entrepreneurs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Frame of Reference

2.1. Institutionalized Practices in the AEC Industry and Sustainability Professionals

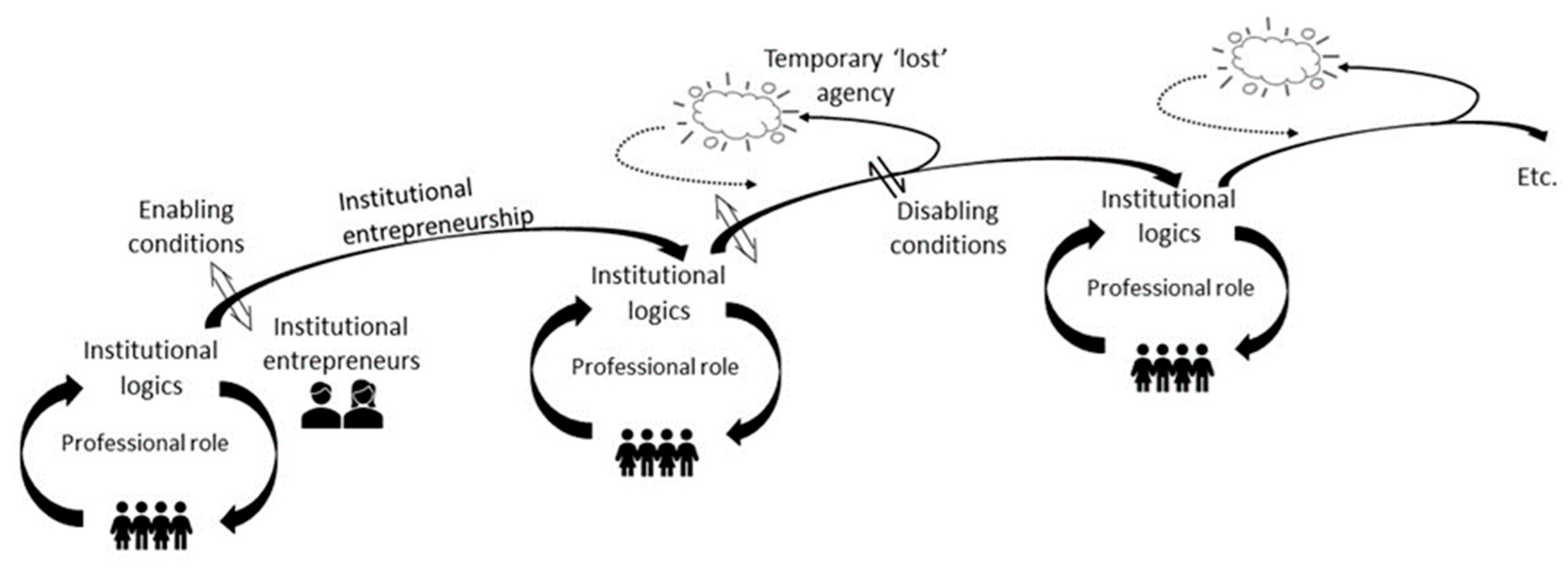

2.2. Institutional Entrepreneurship and Institutional Work

3. Research Methodology

4. Findings: A Professionalization Process in Six Episodes

4.1. Episode 1: Increased Environmental Control and the Starting Point for a New Professinal Role

“Back then some questions were very high priority and spoken of, such as the waste issue, and that’s the issue that got the construction sector to start driving environmental issues overall.”(EM8)

“It was such a wake-up call for them, realizing that we can’t continue like this, we need to know what we are doing.”(EM4)

“People were using trial and error and had ideas on how to handle it. That’s where the journey began where we worked together in the construction sector to bring these things forward...”(EM4)

“And the thing is…that was when my thinking about environmental issues and climate change and how my role in driving my work was formed. Already in my thinking I needed to have an end goal [in mind] and then use back casting to…know what ‘do I need to do today’ but also what kind of [construction] projects are available and ‘how can I use those projects to meet this end goal’.”(EM1)

“(…) according to my memory you had to drive things very hard, you had to push it forward. These things were not something that was taken as a granted and given thing, or something that was high on the top managers’ agenda. You always had to fight for your cause. I worked with both environment and quality, and who likes routines and writing papers? (…) and what I felt like was that environmental or sustainability questions were a constant nagging.”(EM5)

4.2. Episode 2: The Arrival of Environmental Management and Assessment Systems

“So, a lot of individuals felt that those [new tasks] were extra tasks on top of their current tasks. Not a separate role, nor an extended role, these tasks were just dumped upon an existing workload.”(EM4)

“It was common back then that you didn’t have a specific environmental manager. Someone had the responsibility, basically because someone had to have it.”(EM1)

“…but if you look at the environmental/sustainability role. Well you could say that back when I started, we had environmental coordinators and such that started popping up, and this would have been at the end of the 1990s or something like that. And then it was quite common to hire an environmental coordinator that took care of the environmental program and he or she was pretty much given only that…”(EM2)

“…and that was so nice because someone in the group would say something [laughter] and then word would spread, and I noticed in the following days that when I was educating the other groups it was so much easier. So, it’s important to find those ambassadors, the ones that can help get your message spread.”(EM5)

“I didn’t have top management with me from the start, so I was out and about in the country a lot just talking to people and trying to make a change from the outside in so to speak. You got to push and shove a little here and there, you know ‘where is the window open’, find it and jump through it. I can’t go in a straight line from A to B, I have to find my ambassadors and others to say the same things I am saying, think the way I think, and find the little things and the examples, all to increase confidence in this. So, it’s kind of an advanced way of working.”(EM7)

4.3. Episode 3: Staffing a Powertrain towards Sustainability

“So, I think that environmental managers entered the executive office during the 2000s, …and that was when it became a profession since that’s when we started to notice competition in this.”(EM4)

“The environmental assessment systems helped to raise these issues since it is more or less a quality system for environmental issues, meaning requirements can be set in a way that a dialogue can be started. That one can agree on the meaning instead of just throwing together something fluffy and unclear in a document.”(EM2)

4.4. Episode 4: Speeding up the Pace through the Means of Energy Efficiency

“We have not really talked about climate change up until the last couple of years, we have gone from talking waste, to chemicals, and to an energy dialogue.”(EM4)

“… you have this combination of a specific company and the entire industry that are always [difficult]... you can do some things yourselves but then these issues have to be brought forward by the entire industry to have effect.”(EM8)

“Already back then we had a closed loop perspective, but we had a lot of backlash in the form of ‘no we can’t do it that way, there is no point since we’re never going to disassemble this’ etc., but now it’s a main point of concern for the planner to know what will happen in the next life cycle step. So… things have happened the past 25 years and that is always something...”(EM2)

4.5. Episode 5: The Sustainability Crossing—Adding Social Sustainability to the Repertoire

“Social sustainability became a thing in 2012/2013 and was one of those ‘oh where to put it’ things. And in this organization, it was put on me.”(EM8)

“…there is a breakthrough when the financial world starts to make demands, then it becomes natural to include someone with environmental expertise from the beginning.”(EM2)

“Then you renamed the environmental manager to sustainability manager but didn’t really understand what it involved (…), we talked about sustainability, but it was for a while more focused on social sustainability. And therefore, a lot of the sustainability roles were placed within HR.”(EM4)

“You have to look at it from a holistic perspective or else it’s going to backfire completely. But it’s also really frustrating when everyone is walking around in a sort of collective incompetence and think you can just set a bunch of climate goals and achieve sustainability through that when that isn’t going to happen.”(EM7)

4.6. Episode 6: Global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Holistic Turn

“Another big difference is that back in 2000, when I started, there were no articles in the newspapers on the environment. If I were to try and find one, I would have to spend weeks until I’d find one in the daily newspapers. Today you can find articles on the state of the environment, the climate and the planet daily. I don’t think there are any major newspapers who don’t cover that these days.”(EM4)

“One big difference is that back then I had to spend more effort explaining why we had to do things. Today, most people know we have to do these things, and why it’s needed. Nowadays it’s more of a how than a why. The why we answered in the past, now it’s more: well how the heck are we going to do this?”(EM7)

5. Discussion

5.1. Critical Incidents as Enabling and Disabling Conditions

5.2. Environmental Managers’ Strategies for Institutional Entrepreneurship

6. Conclusions

- Interorganizational mobilization to create shared sustainability practices;

- Finding internal ambassadors that can support the diffusion of sustainability practices;

- Creating organizational structure and redefining institutional arrangements;

- Changing positions within and between organizations;

- Mobilizing resources and seizing opportunities for going beyond environmental compliance requirements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hagbert, P.; Malmqvist, T. Actors in transition: Shifting roles in Swedish sustainable housing development. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2019, 34, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolthuis, R.K.; Hooimeijer, F.; Bossink, B.; Mulder, G.; Brouwer, J. Institutional entrepreneurship in sustainable urban development: Dutch successes as inspiration for transformation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A.; Ahmed, V.; Cruickshank, H. Leadership style of sustainability professionals in the UK construction industry. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2015, 5, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, A.; Cruickshank, H.; Ahmed, V. Organizational leadership role in the delivery of sustainable construction projects in UK. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2015, 5, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Viale, T.P. Professionals and field-level change: Institutional work and the professional project. Curr. Sociol. 2011, 59, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Shaping the Future of Construction: A Breakthrough in Mindset and Technology; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/shaping-the-future-of-construction-a-breakthrough-in-mindset-and-technology (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Boverket. Miljöpåverkan från bygg- och fastighetsbranschen 2014; 2014:23; Boverket: Karlskrona, Sweden, 2014; Available online: shorturl.at/huxEG (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Battilana, J.; Leca, B.; Boxenbaum, E. How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 65–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.C. The critical incident technique. Psychol. Bull. 1954, 51, 327–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzio, D.; Brock, D.M.; Suddaby, R. Professions and institutional change: Towards an institutionalist sociology of the professions. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 699–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Viale, T.; Gendron, Y. Reflexivity: The role of embedded social position and entrepreneurial social skill in processes of field level change. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Rockmann, K.W.; Kaufmann, J.B. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, S. Knowing and learning in practice-based studies: An introduction. Learn. Organ. 2009, 16, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.B.-D.; Lieftink, B.M.; Lauche, K. How to claim what is mine: Negotiating professional roles in inter-organizational projects. J. Prof. Organ. 2019, 6, 128–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieftink, B.; Smits, A.; Lauche, K. Dual dynamics: Project-based institutional work and subfield differences in the Dutch construction industry. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. The construction industry as a loosely coupled system: Implications for productivity and innovation. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2002, 20, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P.; Räisänen, C. What tensions obstruct an alignment between project and environmental management practices? Eng. Const. Arch. Manag. 2012, 19, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P. Unfolding roles and identities of professionals in construction projects: Exploring the informality of practices. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2009, 27, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P.; Bosch-Sijtsema, P. Conceptualizing environmental expertise through the lens of institutional work. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2016, 34, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Suddaby, R. Institutions and institutional work. In The Sage Handbook of Organization Studies, 2nd ed.; Clegg, S., Hardy, C., Lawrence, T., Nord, W., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2006; pp. 215–254. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J.; D’aunno, T. Institutional work and the paradox of embedded agency. In Institutional Work: Actors and Agency in Institutional Studies of Organizations; Lawrence, T., Suddaby, R., Leca, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Battilana, J. Agency and institutions: The enabling role of individuals’ social position. Organization 2006, 13, 653–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C.; Suddaby, R.; Sahlin, K. Institutional entrepreneurship. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; SAGE Publications: SAGE Business Cases Originals: London, UK, 2008; pp. 198–217. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, S.; Hardy, C.; Lawrence, T.B. Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 657–679. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Jennings, P.D. The BP oil spill as a cultural anomaly? Institutional context, conflict, and change. J. Manag. Inq. 2011, 20, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzion, D.; Ferraro, F. The role of analogy in the institutionalization of sustainability reporting. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, S. Environmental managers as institutional entrepreneurs: The influence of institutional and technical pressures on waste management. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F.; Grosvold, J. Environmental managers and institutional work: Reconciling tensions of competing institutional logics. Bus. Ethic. Q. 2017, 27, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Doing Interviews; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Månsson, S. Creating an Environmental Sustainability Profession. Technical Report no L2021:125. Licentiate Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gremler, D.D. The critical incident technique in service research. J. Serv. Res. 2004, 7, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvarnström, S. Difficulties in collaboration: A critical incident study of interprofessional healthcare teamwork. J. Interprofessional Care 2008, 22, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenberg, A.-C.; Räisänen, C. The interpretative “green” in the building: Diachronic and synchronic. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2006, 36, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P. Building Green-Perspectives on Environmental Management in Construction. Report serie: Doktorsavhandlingar Ny serie no 2411. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, H.; Brunklaus, B.; Gluch, P.; Kadefors, A.; Stenberg, A.C.; Thuvander, L. Miljöbarometern för byggsektorn 2002; Report ESA 2003:02; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- SBUF Byggsektorns betydande miljöaspekter; SBUF Informerar, no 01:10: Stockholm, Sweden. 2001. Available online: shorturl.at/tAI39 (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Sjölander-Lindqvist, A. In Understanding aspects of environmental stigma: The case of Hallandsås, Foresight and Precaution. In Proceedings of the ESREL 2000 and SRA-Europe Annual Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 14–17 May 2000; Cottam, M.P., Harvey, D.W., Pape, R.P., Tait, J., Eds.; CRC Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2000; pp. 1053–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg, A.-C. The Social Construction of Green Building: Diachronic and Synchronic Perspectives. Report serie: Doktorsavhandlingar Ny serie no 2442. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, April 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, E. Green Procurement of Buildings: Estimation of Environmental Impact and Life-Cycle Cost. Report 2002:09. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå Tekniska Universitet, Luleå, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, K. Monitoring as an Instrument for Improving Environmental Performance in Public Authorities: Experience from Swedish Infrastructure Management. Report serie: Trita-LWR. Ph.D. Thesis, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Stockholm, Sweden, April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, T. Fastighetsförvaltning med miljöproblemen i fokus: Om miljöstyrning och uppföljning av minskad miljöpåverkan i fastighetsförvaltande organisationer. Report serie: TRITA-INFRA. In Licentiate Thesis; Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan: Stockholm, Sweden, February 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brunklaus, B. Organising Matters for the Environment: Environmental Studies of Housing Management and Buildings. Report serie: Doktorsavhandlingar Ny serie no 2894. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gluch, P.; Brunklaus, B.; Johansson, K.; Lundberg, Ö.; Stenberg, A.C.; Thuvander, L. Miljöbarometern för bygg- och fastighetssektorn 2006—en kartläggning av sektorns miljöarbete; CMB-report; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hyödynmaa, M. Miljöledning i Byggföretag: Motiv, Möjligheter och Hinder. Report serie: TRITA-IEO. Licentiate Thesis, Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan, Stockholm, Sweden, March 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, T.; Glaumann, M.; Svenfelt, Å.; Carlson, P.-O.; Erlandsson, M.; Andersson, J.; Wintzell, H.; Finnveden, G.; Lindholm, T.; Malmström, T.-G. A Swedish environmental rating tool for buildings. Energy 2011, 36, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P.; Gustafsson, M.; Thuvander, L.; Baumann, H. Charting corporate greening: Environmental management trends in Sweden. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 42, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallhagen, M.; Glaumann, M.; Eriksson, O.; Westerberg, U. Framework for detailed comparison of building environmental assessment tools. Buildings 2013, 3, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nässén, J.; Sprei, F.; Holmberg, J. Stagnating energy efficiency in the Swedish building sector—Economic and organisational explanations. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 3814–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, L.; Lind, H.; Grange, K. Incentives for improving energy efficiency when renovating large-scale housing estates: A case study of the Swedish million homes programme. Sustainability 2009, 1, 1349–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P. Hållbart Byggande och projektbaserad organisering: En studie av organiskatoriska flaskhalsar; Research Report 2009:3; Construction Management, Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Thoresson, J. Omställning–Tillväxt–Effektivisering: Energifrågor vid renovering av flerbostadshus. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hagbert, P.; Femenías, P. Sustainable homes, or simply energy-efficient buildings? Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2015, 31, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluch, P. Managerial Environmental Accounting in Construction Projects. Licentiate Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, May 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, D. Let the Right Ones in? Employment Requirements in Swedish Construction Procurement. Technical report no. L2018:093. Licentiate Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden, January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment. The Climate Policy Framework. Available online: https://www.government.se/articles/2017/06/the-climate-policy-framework/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Westlund, P.; Brogren, M.; Hylander, B.; Kellner, J.; Linden, C.; Lönngren, Ö.; Nordling, J.; Strömberg, L.; Winberg, F. Klimatpåverkan från byggprocessen; Kungl. Ingenjörsvetenskapsakademien (IVA): Stockholm, Sweden, 2014; Available online: https://www.iva.se/publicerat/klimatpaverkan-fran-byggprocessen/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Ejlertsson, A.; Green, J.; Ahlm, M. Cirkulär ekonomi i byggbranschen; Svenska Miljöinstitutet IVL: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Malmqvist, T.; Nehasilova, M.; Moncaster, A.; Birgisdottir, H.; Rasmussen, F.N.; Wiberg, A.H.; Potting, J. Design and construction strategies for reducing embodied impacts from buildings–Case study analysis. Energy Build. 2018, 166, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverige, F. Färdplan för fossilfri konkurrenskraft bygg- och anläggningssektorn; Fossilfritt Sverige: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Troje, D.; Gluch, P. Populating the social realm: New roles arising from social procurement. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2020, 38, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Manager | Length of Interview | Years of Experience 1 | Types of Organizational Employers |

|---|---|---|---|

| EM1 | 90 min | 21 | Construction, construction clients |

| EM2 | 150 min | 25 | Construction |

| EM3 | 100 min | 39 | Construction |

| EM4 | 90 min | 19 | Construction |

| EM5 | 60 min | 25 | Construction, real estate, architecture |

| EM6 | 60 min | 29 | Real estate, architecture |

| EM7 | 60 min | 23 | Construction, construction clients |

| EM8 | 60 min | 34 | Construction |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gluch, P.; Månsson, S. Taking Lead for Sustainability: Environmental Managers as Institutional Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074022

Gluch P, Månsson S. Taking Lead for Sustainability: Environmental Managers as Institutional Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074022

Chicago/Turabian StyleGluch, Pernilla, and Stina Månsson. 2021. "Taking Lead for Sustainability: Environmental Managers as Institutional Entrepreneurs" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074022

APA StyleGluch, P., & Månsson, S. (2021). Taking Lead for Sustainability: Environmental Managers as Institutional Entrepreneurs. Sustainability, 13(7), 4022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074022