Rediscovering Herb Lane: Application of Design Thinking to Enhance Visitor Experience in a Traditional Market

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

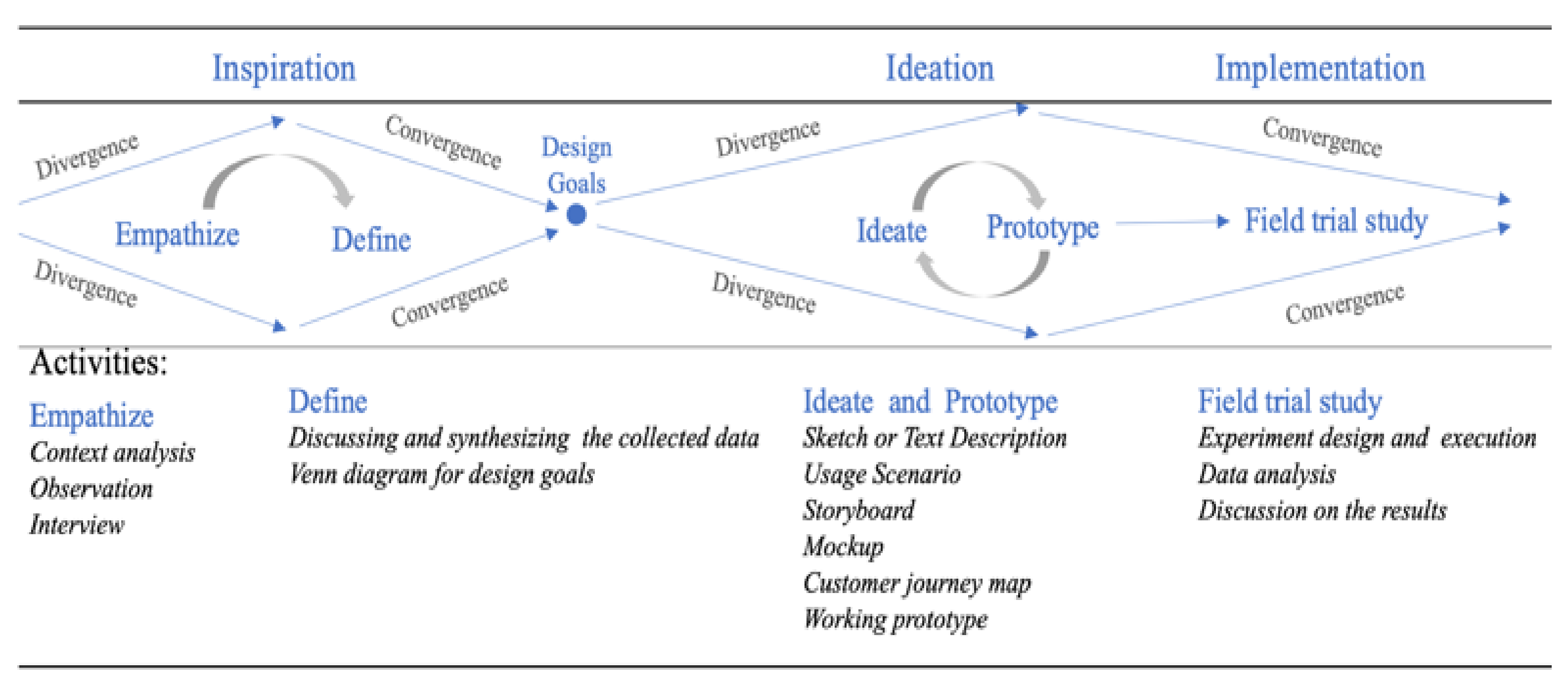

2.1. Design Thinking

2.2. Technology for Enhancing Visitor Experiences in Cultural Attractions

3. Methodology

4. A Participatory Case Study

4.1. Inspiration Stage

4.2. Ideation Stage

4.3. Implementation Stage

4.3.1. Participants and Procedure

4.3.2. Measurement Tools

4.3.3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzalez, S.; Waley, P. Traditional retail markets: The new gentrification frontier? Antipode 2013, 45, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shakur, T.; Hafiz, R.; Arslan, T.V.; Cahantimur, A. Economy and culture in transitions: A comparative study of two architectural heritage sites of bazars and Hans of Bursa and Dhaka. ArchNet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2012, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.-M.; Gim, T.-H.T. What makes an old market sustainable? An empirical analysis on the economic and leisure performances of traditional retail markets in Seoul. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zakariya, K.; Kamarudin, Z.; Harun, N.Z. Sustaining the cultural vitality of urban public markets: A case study of Pasar Payang, Malaysia. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Arch. Res. 2016, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zandieh, M.; Seifpour, Z. Preserving traditional marketplaces as places of intangible heritage for tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.; Seale, K. Informal Urban Street Markets: International Perspectives; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Uriely, N. The tourist experience: Conceptual developments. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.-W.; Wu, M. Rediscover Herbal Lane-Enhancing the Tourist Experience Through Mobile Applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cross-Cultural Design, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart tourism destinations. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014; Springer: Singapore, 2013; pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Buonincontri, P.; Marasco, A. Enhancing cultural heritage experiences with smart technologies: An integrated experiential framework. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 17, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsopoulos, K.I.; Chourdaki, P.; Tsolis, D.; Antoniadis, R.; Pavlidis, G.; Assimakopoulos, N. An authoring platform for developing smart apps which elevate cultural heritage experiences: A system dynamics approach in gamification. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, D.; Ciolfi, L.; van Dijk, D.; Hornecker, E.; Not, E.; Schmidt, A. Integrating material and digital: A new way for cultural heritage. Interactions 2013, 20, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V.P.; Fixson, S.K. Adopting design thinking in novice multidisciplinary teams: The application and limits of design methods and reflexive practices. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-K. Revitalising traditional street markets in rural Korea: Design thinking and sense-making methodology. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2019, 38, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jernsand, E.M.; Kraff, H.; Mossberg, L. Tourism experience innovation through design. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15 (Suppl. 1), 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Erschbamer, G.; Pechlaner, H. Destination design: New perspectives for tourism destination development. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sándorová, Z.; Repáňová, T.; Palenčíková, Z.; Beták, N. Design thinking—A revolutionary new approach in tourism education? J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 26, 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, G.T.; Clausen, H.B. Fostering innovation competencies in tourism higher education via design-based and value-based learning. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesenmaier, D.R.; Xiang, Z. Design Science in Tourism: Foundations of Destination Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, P.; Devitt, F. Collaboration, creativity and entrepreneurship in tourism: A case study of how design thinking created a cultural cluster in Dublin. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Z.; Stienmetz, J.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smart tourism design: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on designing tourism places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 86, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliñski, G.; Studziñska, M. Application of design-thinking models to improve the quality of tourism services. Zarzdzanie Finans. J. Manag. Financ. 2015, 13, 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, N. Designerly ways of knowing: Design discipline versus design science. Des. Issues 2001, 17, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koskinen, I.; Zimmerman, J.; Binder, T.; Redstrom, J.; Wensveen, S. Design research through practice: From the lab, field, and showroom. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2013, 56, 262–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardzell, J.; Bardzell, S.; Dalsgaard, P.; Gross, S.; Halskov, K. Documenting the research through design process. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Brisbane, Australia, 4–8 June 2016; pp. 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Huppatz, D.J. Design thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.; Martin, R.L. The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking is the Next Competitive Advantage; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, N.V. Design thinking and food innovation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 41, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Design Council. What Is the Framework for Innovation? Design Council’s Evolved Double Diamond; Design Council: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dam, R.; Siang, T. 5 Stages in the Design Thinking Process. Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/5-stages-in-the-design-thinking-process (accessed on 4 April 2021).

- Fierst, K.; Diefenthaler, A.; Diefenthaler, G. Design Thinking for Educators; IDEO: Riverdale, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vianna, M.; Vianna, Y.; Adler, I.K.; Lucena, B.; Russo, B. Design Thinking:Business Innovation; MJV Technology & Innovation: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Wyatt, J. Design thinking for social innovation. Dev. Outreach 2010, 12, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, T.; Gumienny, R.; Jobst, B.; Meinel, C. Is There a Need for a Design Thinking Process? In Proceedings of the Design Thinking Research Symposium 8 (Design 2010), Sydney, Australia, 9–20 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani, S. Visual design thinking: A collaborative dimensions framework to profile visualisations. Des. Stud. 2019, 63, 92–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewenstein, B.; Whyte, J. Knowledge practices in design: The role of visual representations asepistemic objects’. Organ. Stud. 2009, 30, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whyte, J.K.; Ewenstein, B.; Hales, M.; Tidd, J. Visual practices and the objects used in design. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M.J.; Burkhard, R.A. Visual representations in knowledge management: Framework and cases. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stappers, P.J.; Valentine, L. Prototypes as a central vein for knowledge development. In Prototype: Design and Craft in the 21st Century; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2013; pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bresciani, S.; Comi, A. Facilitating culturally diverse groups with visual templates in collaborative systems. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2017, 24, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKercher, B.; Ho, P.S.; Du Cros, H. Attributes of popular cultural attractions in Hong Kong. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chen, F.-S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Folgado-Fernández, J.A. Healthy water-based tourism experiences: Their contribution to quality of life, satisfaction and loyalty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Affirming authenticity: Consuming cultural heritage. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ritchie, B., Jr.; McCormick, B. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingram, H.; McKercher, B.; Du Cros, H. Cultural Tourism: The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu, Y.; Sato, F.; Ito, A.; Hatano, H.; Sato, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Sasaki, A. Designing mobile application to motivate young people to visit cultural heritage sites. Int. J. Soc. Bus. Sci. 2017, 11, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, K.-P.; Peng, N.; Chen, A. Incorporating on-site activity involvement and sense of belonging into the Mehrabian-Russell model—The experiential value of cultural tourism destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, I.A.; Tang, S.L.W. Linking travel motivation and loyalty in sporting events: The mediating roles of event involvement and experience, and the moderating role of spectator type. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 33, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabau-Montoya, J.; Ruiz-Molina, M. Enhancing visitor experience with war heritage tourism through information and communication technologies: Evidence from Spanish civil war museums and sites. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, F.; Buono, P.; Desolda, G.; Impedovo, D.; Piccinno, A. Improving smart interactive experiences in cultural heritage through pattern recognition techniques. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 131, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasinger, J.; Fuchs, M.; Höpken, W. Information search with mobile tourist guides: A survey of usage intention. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2007, 9, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscheu, F.; Buhalis, D. Augmented reality at cultural heritage sites. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2016; Inversini, A., Schegg, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 607–619. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Oliva, A.; Alvarado-Uribe, J.; Parra-Meroño, M.C.; Jara, A.J. Transforming communication channels to the co-creation and diffusion of intangible heritage in smart tourism destination: Creation and testing in ceutí (Spain). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solima, L.; Izzo, F. QR codes in cultural heritage tourism: New communications technologies and future prospects in Naples and Warsaw. J. Herit. Tour. 2018, 13, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sanagustín, M.; Parra, D.; Verdugo, R.; García-Galleguillos, G.; Nussbaum, M. Using QR codes to increase user engagement in museum-like spaces. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, H.M.; Gross, M. Teaching sustainability via smartphone-enhanced experiential learning in a botanical garden. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. (iJIM) 2014, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, K.H.; Shaikh, S.P. Design of a mobile garden guide based on Artcodes. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on User Science and Engineering (i-USEr), Melaka, Malaysia, 23–25 August 2016; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Koleva, B.; Bedwell, B.; Benford, S. Deepening visitor engagement with museum exhibits through hand-crafted visual markers. In Proceedings of the 2018 on Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI, Chicago, IL, USA, 23–25 May 2018; pp. 523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Klemm, W.; Lenzholzer, S.; Brink, A.V.D. Developing green infrastructure design guidelines for urban climate adaptation. J. Landsc. Arch. 2017, 12, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernbach, S.; Nabergoj, A.S. Visual design thinking: Understanding the role of knowledge visualization in the design thinking process. In Proceedings of the 2018 22nd International Conference Information Visualisation (IV), Salerno, Italy, 10–13 July 2018; pp. 362–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, C.; Alves, H. A customer journey approach. In The Routledge Handbook of Service Research Insights and Ideas; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; p. 344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Ma, L. The influences of information overload and social overload on intention to switch in social media. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebejer, J.; Smith, A.; Stevenson, N.; Maitland, R. The tourist experience of heritage urban spaces: Valletta as a case study. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 17, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsi, R.L.; Olson, J.C. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Visitor Experience | Condition | N | Mean (SD) | T Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedonism | With App | 55 | 5.42 (0.86) | 5.14 *** |

| Without app | 59 | 4.53 (1.00) | ||

| Novelty | With App | 55 | 5.92 (0.86) | 4.89 *** |

| Without app | 59 | 5.06 (0.99) | ||

| Local Culture | With App | 55 | 5.50 (1.16) | 3.16 ** |

| Without app | 59 | 4.86 (0.98) | ||

| Involvement | With App | 55 | 5.39 (0.93) | 4.71 *** |

| Without app | 59 | 4.52 (1.04) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tung, F.-W. Rediscovering Herb Lane: Application of Design Thinking to Enhance Visitor Experience in a Traditional Market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074033

Tung F-W. Rediscovering Herb Lane: Application of Design Thinking to Enhance Visitor Experience in a Traditional Market. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074033

Chicago/Turabian StyleTung, Fang-Wu. 2021. "Rediscovering Herb Lane: Application of Design Thinking to Enhance Visitor Experience in a Traditional Market" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 4033. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074033