Transition towards Smart City: The Case of Tallinn

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

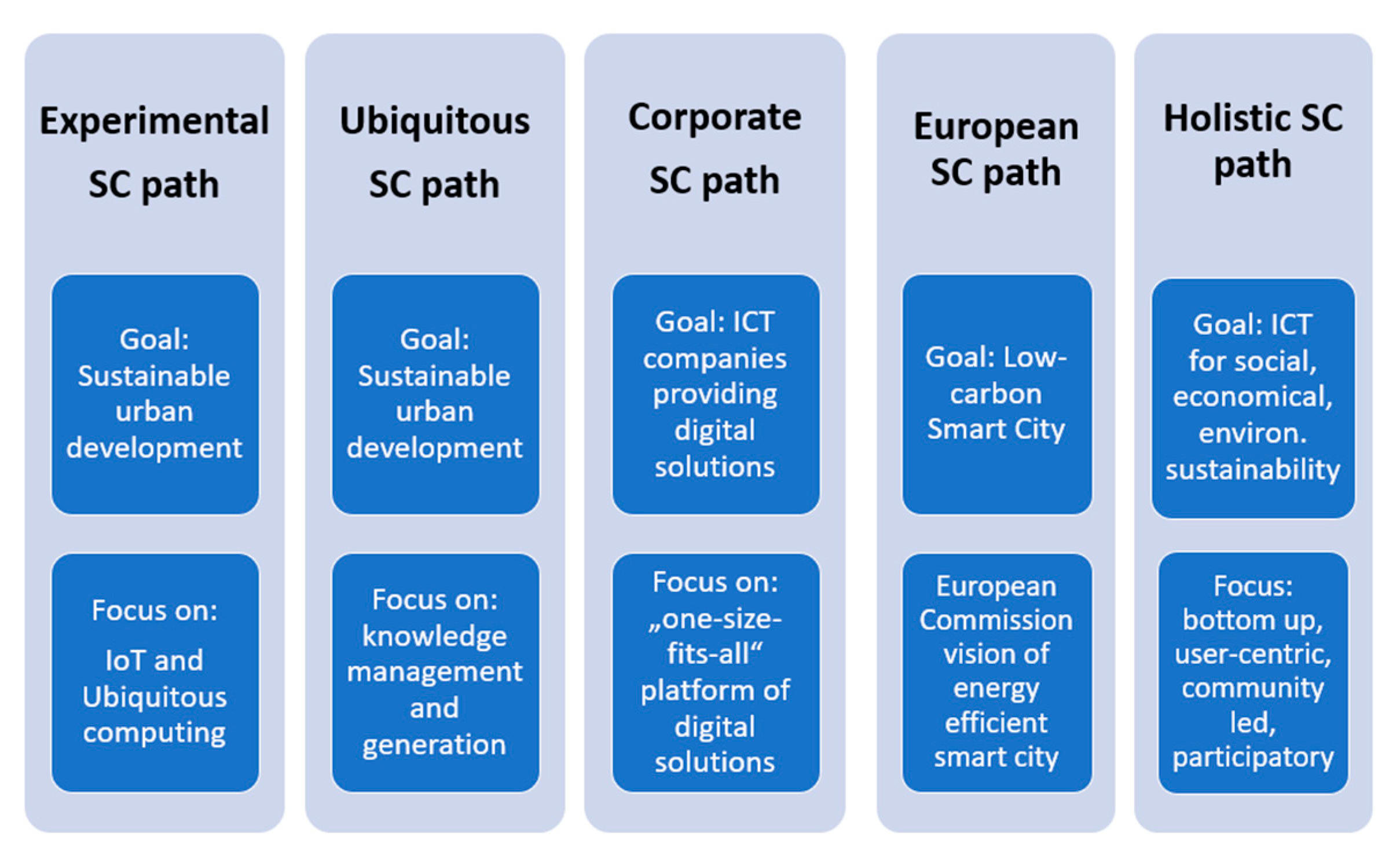

1.2. Definition of the SC Concept

1.3. Overview of SC Collaboration Models and Best Practices Literature

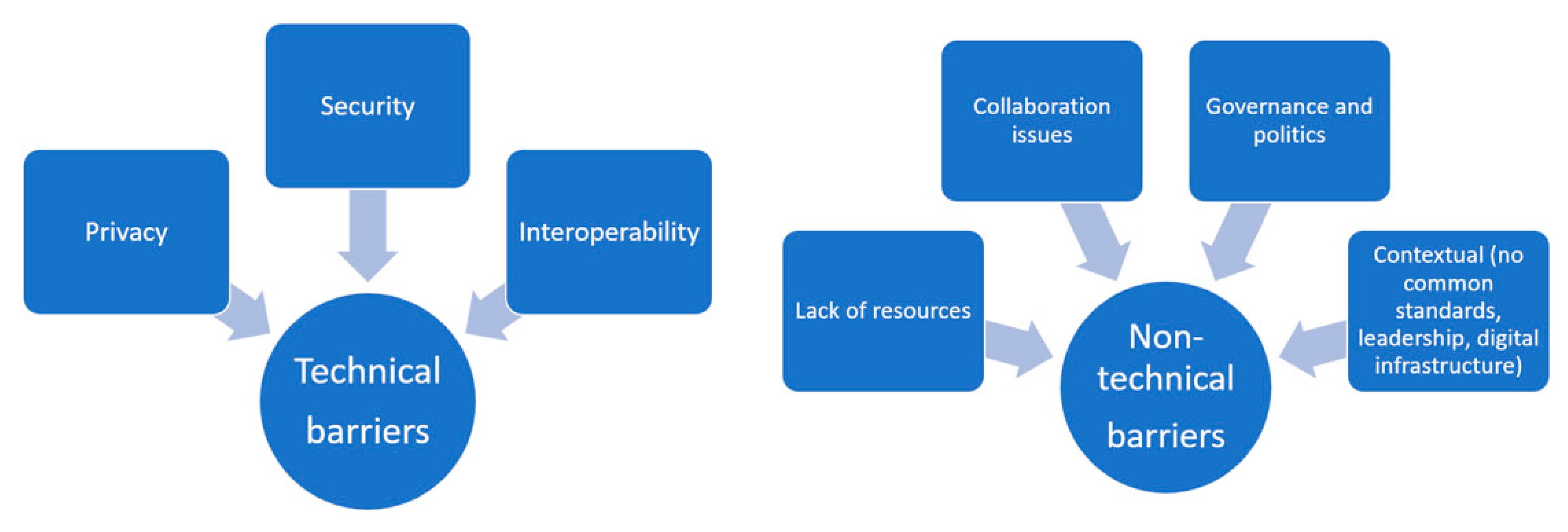

1.4. Smart City Barriers

2. Conceptual Framework and Methods

2.1. SC Dichhotomies Framework

2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews with Tallinn City Officials

2.3. Description of the Tallinn 2035 City Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Interview Results from the SC Dichotomies Perspective

3.1.1. Technology-Led versus Holistic Approach

3.1.2. Double- versus Quadruple-Helix Model of Collaboration

3.1.3. Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Approach

3.1.4. Interpreted Barriers for SC Development

3.2. Tallinn 2035 in the Context of Dichotomies

“The city governance is based on a social agreement between the citizens, which is expressed in the city development strategy. The development strategy is the basis for general plans and sectoral development documents. Planning is an ongoing process in which plans are updated based on monitoring results. The decision-making process is open and involves citizens”.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandez-Anez, V.; Fernández-Güell, J.M.; Giffinger, R. Smart City implementation and discourses: An integrated con-ceptual model. The case of Vienna. Cities 2018, 78, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, T. An investigation of IBM’s smarter cites challenge: What do participating cities want? Cities 2017, 63, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, D.; Alizadeh, T. What makes Indian cities smart? A policy analysis of smart cities mission. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 55, 101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S.; Molella, A.P. The eco-city as urban technology: Perspectives on Caofeidian international eco-city (China). J. Urban Technol. 2013, 20, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmud, J.; Sener, I.N.; Wagner, J. Self-driving vehicles: Determinants of adoption and conditions of usage. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2016, 2565, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Olsson, A.R.; Håkansson, M. The role of local governance and environmental policy integration in Swedish and Chinese eco-city development. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenniemi, H.; Huovila, A. How do cities promote urban sustainability and smartness? An evaluation of the city strategies of six largest Finnish cities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4174–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Smart Cities and Communities—European Innovation Communication from the Commission. 2012. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/smart-cities-and-communities-european-innovation-partnership-communication-commission-c2012 (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Hollands, R.G. Will the real smart city please stand up? City 2008, 12, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albino, V.; Berardi, U.; Dangelico, R.M. Smart cities: Definitions, dimensions, performance, and initiatives. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Bolici, R.; Deakin, M. The first two decades of smart-city research: A bibliometric analysis. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Deakin, M.; Reid, A. Combining co-citation clustering and text-based analysis to reveal the main development paths of smart cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Deakin, M.; Reid, A. Smart city development paths: insights from the first two decades of research. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Region: Results of SSPCR 2017; Bisello, A., Vettorato, D., Laconte, P., Costa, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 403–427. [Google Scholar]

- Komninos, N.; Mora, L. Exploring the big picture of smart city research. Scienze Regionali 2018, 1, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, L.; Deakin, M.; Reid, A. Strategic principles for smart city development: A multiple case study analysis of European best practices. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 142, 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S. Future cities: asserting public governance. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; de Jong, M.; Heuvelhof, E.T. Explaining the variety in smart eco city development in China-What policy network theory can teach us about overcoming barriers in implementation? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Smart city as urban innovation: focusing on management, policy, and context. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV ‘11), Tallinn, Estonia, 26–28 September 2011; pp. 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Dameri, R.P.; Rosenthal-Sabroux, C. (Eds.) Smart City: How to Create Public and Economic Value with High Technology in Urban Space; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; 238p. [Google Scholar]

- Papa, R.; Gargiulo, C.; Galderisi, A. Towards an urban planners’ perspective on smart city. Tema J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2013, 6, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes, A.L.A.; Alvarenga, J.C.; Goulart, M.D.S.S.; Rodriguez, M.V.R.Y.; Soares, C.A.P. Smart cities: The main drivers for increasing the intelligence of cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.; Vairinhos, V.; Osinski, M. Intellectual capital management as an indicator of sustainability. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Knowledge Management, Barcelona, Spain, 7–8 September 2017; pp. 655–663. [Google Scholar]

- Dameri, R.P. Searching for smart city definition: A comprehensive proposal. Int. J. Comput. Technol. 2013, 11, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M. Smart city policies: A spatial approach. Cities 2014, 41, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L.; Deakin, M. The triple-helix model of smart cities: A neo-evolutionary perspective. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, D. IBM and the visual formation of smart cities. In Smart Urbanism: Utopian Vision or False Dawn? Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 34–51. [Google Scholar]

- Söderström, O.; Paasche, T.; Klauser, F. Smart cities as corporate storytelling. City 2014, 18, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juujärvi, S.; Pesso, K. Actor roles in an urban living lab: What can we learn from Suurpelto, Finland? Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayangsari, L.; Novani, S. Multi-stakeholder co-creation Analysis in Smart city Management: An Experience from Bandung, Indonesia. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 4, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, Z.D.W.; van der Knaap, W.G.M. Urban innovation system and the role of an open web-based platform: The case of Amsterdam smart city. J. Reg. City Plan. 2018, 29, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P. The conceptual idea of smart city: University, industry, and government vision. In Smart City Implementation; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, L.; Reid, A.; Angelidou, M. The current status of smart city research: exposing the division. In Smart Cities in the Post-algorithmic Era; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Angelidou, M. The role of smart city characteristics in the plans of fifteen cities. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigea, A.; Papadopoulou, C.-A.; Panagiotopoulou, M. Tools and Technologies for planning the development of smart cities. J. Urban Technol. 2015, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Colding, M.; Barthel, S. The smart city model: A new panacea for urban sustainability or unmanageable complexity? Environ. Plan. B: Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R. Making sense of smart cities: Addressing present shortcomings. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2014, 8, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niebel, T. ICT and economic growth comparing developing, emerging and developed countries. SSRN Electron. J. 2014, 104, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Deakin, M.; Zhang, X.; Batty, M.; de Jong, M.; Santi, P.; Appio, F.P. Assembling sustainable smart city transitions: An interdisciplinary theoretical perspective. J. Urban Technol. 2021, 28, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, J.; Bendor, R. Selling smartness: Corporate narratives and the smart city as a sociotechnical imaginary. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2019, 44, 540–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tödtling, F.; Trippl, M. One size fits all? Towards a differentiated regional innovation policy approach. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1203–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, P.; Andersson, B. Challenges with smart cities initiatives: A municipal decision makers perspective. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2017; pp. 2804–2813. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Pardo, T.A.; Nam, T. What makes a city smart? Identifying core components and proposing an integrative and comprehensive conceptualization. Inf. Polity 2015, 20, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. The case study crisis: Some answers. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Deakin, M.; Reid, A.; Angelidou, M. How to overcome the dichotomous nature of smart city research: Proposed methodology and results of a pilot study. J. Urban Technol. 2019, 26, 89–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T.A. Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Digital Government Research Conference on Digital Government Innovation in Challenging Times, College Park, MD, USA, 12–15 June 2011; pp. 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Sarv, L.; Kibus, K.; Soe, R.-M. Smart city collaboration model: a case study of university-city collaboration. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV 2020), Athens, Greece, 23–25 September 2020; pp. 674–677. [Google Scholar]

- Sootla, G.; Kattai, K. Institutionalization of subnational governance in Estonia: European impacts and domestic adaptations. Reg. Fed. Stud. 2020, 30, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, R.-M. FINEST Twins: Platform for cross-border smart city solutions. In dg.o ’17: Proceedings of the 18th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research; Hinnant, C.C., Ojo, A., Eds.; ACM: Staten Island, NY, USA; pp. 352–357. [CrossRef]

- Soe, R.-M. Smart Twin Cities via Urban Operating System. In ICEGOV ’17: Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance; Baguma, R., De, R., Janowski, T., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 391–400. [CrossRef]

- Soe, R.-M.; Müür, J. Mobility acceptance factors of an automated shuttle bus last-mile service. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, R.-M. Innovation procurement as key to cross-border ITS pilots. Int. J. Electron. Gov. 2020, 12, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristvej, J.; Lacinák, M.; Ondrejka, R. On smart city and safe city concepts. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2020, 25, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dichotomies | Strategic Principle |

|---|---|

| Dichotomy 1: Technology-led or holistic strategy | Hypothesis 1.1: Technology-led strategy |

| Hypothesis 1.2: Holistic strategy | |

| Dichotomy 2: Double- or quadruple-helix model of collaboration | Hypothesis 2.1: Double-helix model of collaboration |

| Hypothesis 2.2: Quadruple-helix model of collaboration | |

| Dichotomy 3: Top-down or bottom-up approach | Hypothesis 3.1: Top-down approach |

| Hypothesis 3.2: Bottom-up approach | |

| Dichotomy 4: Mono-dimensional or integrated intervention logic | Hypothesis 4.1: Mono-dimensional intervention logic |

| Hypothesis 4.2: Integrated intervention logic |

| Interview | Role | Why Is Relevant for SC Development | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewee #1 | Head of Strategy | Leader of the Tallinn 2035 strategy workgroup | 26 June 2020 |

| Interviewee #2 | Head of Tallinn Smart City Competence Center | Responsible for collaboration with International City networks, R&D project development coordination (H2020, Inrterreg, Urbact, UIA and others) | 29 June 2020 |

| Interviewee #3 | Director of Finance | Responsible for the City finances | 8 July 2020 |

| Interviewee #4 | Project manager at Tallinn Smart City Competence Center | Responsible for smart and sustainable city project development | 10 July 2020 |

| Interviewee #5 | Vice Mayor of Innovation | Responsible for the innovation generation | 4 August 2020 |

| Interviewee #6 | Business Adviser at Tallinn City Enterprise Board | Works on collaboration with companies, offers training and support to start-ups and collaboration with universities. | 4 September 2020 |

| Interviewee #7 | Lead specialist in the City Survey subunit | Works on collaboration with universities and research institutions | 9 September 2020 |

| Interviewee #8 | Chief innovation officer | Background in technology companies, from 2021 Head of Future City unit (data, digital and innovation) | 21 September 2020 |

| No. Inhabitants | Length and Structure of the Strategy | Main Values and Principles of the City | Does the City Indicate Clear Targets, Measures and in What Way Is the Performance Towards the Targets Measured? | CO2 Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 437,619 | 63 pages with no illustrations or photos. There is also an interactive web application with maps, illustrations and photos. | Strategy focuses on sustainability and urban development, education and digitalisation. Six main targets are: 1. Friendly urban space, 2. community, 3. green revolution, 4. world city, 5. proximity to home (15 min to city) 6. healthy and mobile lifestyle. The five main values to follow are: 1. purposefulness in achieving targeted results and curiosity for finding best solutions, 2. cooperation and independence, 3. wisdom and courage to make decisions and take responsibility, 4. reliability and openness of city officials and 5. customer focus and friendliness. | Targets are clearly expressed and monitored yearly (e.g., +2% of enterprises per year for 1000 inhabitants, among top 10 in the rankings of digital and sustainable cities like CityKeys, European Digital City Index, etc.). Measures are described through action plans for each of the six main targets/goals of the city strategy, with sub-targets. There are 30 targets set for 13 different fields: 1. entrepreneurship promotion and innovativeness, 2. education and youth work, 3. environmental protection, 4. safety, 5. culture, 6. mobility, 7. urbanscape, 8. city planning, 9. preservation and development of urban property, 10. social care, 11. sport and recreation; 12. infrastructure and 13. health and healthcare | −40% by 2030 compared to 2007 |

| No. of “Pure” Dichotomy | No. of Mixed | No Data | Dominant Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology-led: 3 | Holistic: 1 | 3 | 1 | Technology-led approach |

| Double-helix or triple-helix–6 | Quadruple-helix | 2 | 0 | Double- or triple-helix |

| Top-down–4 | Bottom-up–1 | 3 | 0 | Top-down |

| Mono-dimensional | Integrated | No data | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarv, L.; Soe, R.-M. Transition towards Smart City: The Case of Tallinn. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084143

Sarv L, Soe R-M. Transition towards Smart City: The Case of Tallinn. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084143

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarv, Lill, and Ralf-Martin Soe. 2021. "Transition towards Smart City: The Case of Tallinn" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084143

APA StyleSarv, L., & Soe, R.-M. (2021). Transition towards Smart City: The Case of Tallinn. Sustainability, 13(8), 4143. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084143