1.1. Background and Objective

With a magnitude already comparable to that of the infamous Spanish influenza, the COVID-19 pandemic has drastically affected people’s lives everywhere [

1]. The world has been struggling with the pandemic for more than a year now. Despite impressively rapid medical and pharmaceutical work developing testing methods, vaccinations, and treatments, the containment of the virus largely depended on individual and organizational behavior. In the course of time, governments imposed measures such as social distancing, strict hygiene instructions, quarantines, facemask obligations, lockdowns, and curfews. In addition to the fatalities and severe physical conditions directly caused by the virus, many studies have drawn attention to its potential side-effects. Aside from warnings of a severe economic backlash in the near future [

2,

3], most urgent warnings involve the pandemic’s effects in the here and now on people’s mental health and well-being [

4,

5,

6].

Many empirical studies, conducted in a wide range of national contexts and in different phases of the pandemic, confirmed that mental health and well-being are threatened by COVID-19, although the magnitude of the effects found varied [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Negative effects confirmed include anxiety, fatigue, stress, insomnia, distress, and depression. An important follow-up research question would be which factors explain people’s state of mental health and well-being in times of COVID-19.

So far, research predominantly aimed at either identifying groups of people with heightened risks or evaluating the effects of psychological resources or interventions. To identify high-risk groups, many studies investigated the relationships of people’s mental health or well-being with a wide range of more or less stable background characteristics. These characteristics can be characterized as “non-modifiable factors” (p. 1 [

13]), which may have already been present before COVID-19 started and which do not necessarily provide clues for developing interventions. Studies, for instance, focused on the relationship of mental health or well-being with demographics [

11,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], living conditions and personal relationships [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

25,

27,

28,

29], lifestyle and media use [

19,

22,

24,

26,

32,

33], psychological traits [

15,

18,

19,

20,

25,

29,

34], physical or mental health status before the pandemic [

11,

12,

14,

18,

22,

24,

25,

27,

29,

30], belonging to recognized high-risk groups [

13,

16], and having COVID cases among family, friends, and acquaintances [

18,

23,

29,

32]. Studies evaluating the effects of psychological resources or interventions focused on preventing or solving mental health problems, either by means of resources people may already have, such as flexibility [

35] or resilience [

29,

36], or by means of trained skills or dispositions, such as stress management [

20] or coping strategies [

25,

32].

Despite their potential value, both types of research do not substantially contribute to our understanding of the causes of the mental problems people have in times of pandemics: Are mental health and well-being affected by people’s fear of the virus, by the loneliness resulting from government measures to contain the virus, or by any other factors triggered by the pandemic? More research is needed on the personal and societal antecedents of mental health and well-being, unraveling how people perceive the many different aspects simultaneously occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic and relating them to their mental health or well-being. The study reported in this article aims to make such a contribution.

Moreover, our study focuses on a specific group of citizens with a unique perspective on the COVID-19 pandemic, whose voice is underexposed in the academic literature: Chinese immigrants in Western countries (in our case, the Netherlands). The unicity of their perspective involves two characteristics. First, since the earliest cases were reported in China, several studies have drawn attention to the rise of stigmatization and racism against Chinese (and, for that matter, Asians in general) as a result of the pandemic [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Most evidence comes from the United States [

37,

39,

40,

41,

42,

45,

46], complemented by studies from the United Kingdom [

38], France [

43], and Canada [

44]. It is imaginable that similar mechanisms occur in other Western countries as well. The rise of stigmatization and racism is fueled by the explicit scapegoating and name-calling (the “China virus”) by Western leaders and must be seen in a broader context of international tensions [

43]. Three of the studies mentioned found that the perceived increase of anti-Asian racism was negatively related to mental health [

37,

44,

46], a finding generically corroborated by a much larger body of research [

47,

48]. Second, Chinese immigrants are in the position to compare the handling of the pandemic in their host country with that in China, combining a heightened interest in developments in both national contexts and having access to Western and Chinese information sources. They were already aware of the dangers of the pandemic when the dominant view in Western countries was that a worldwide outbreak would not happen. They witnessed the differences between the rigorous handling of the pandemic in China and the Western pandemic response, which they saw as weak and flawed. A qualitative study of Chinese immigrants in Spain clearly illustrated this perspective: Participants expressed deep concerns about the nonchalant way their host country dealt with the pandemic [

49]. An ethnographic study in Canada found that Chinese immigrants developed a sense of “double unbelonging” (p. 207), as they could not understand the Western pandemic response and at the same time experienced barriers to return to China due to Chinese border measures [

44].

1.2. Current Insights about COVID-19 and Mental Health and Well-Being

Research on demographics revealed some interesting general tendencies. Regarding gender, many studies found that women are more negatively affected by the pandemic than men [

11,

13,

14,

16,

17,

18,

19,

21,

22,

23,

26,

27,

30,

31]. In contrast, however, one study found that men are more prone to depression than women [

20] and another study drew attention to the mental health of non-binary people, who had the strongest negative response [

14]. Regarding age, research found that younger people are more negatively affected by the pandemic than older people [

11,

13,

15,

16,

20,

21,

25,

28], but some other studies found that people older than 55 are more vulnerable [

19,

31]. Besides this, two studies suggested a differentiation among young people, showing that senior students are more negatively affected than junior students [

23,

29]. Regarding educational level, the research findings were mixed and unclear [

16,

21,

22,

24].

Several studies suggest that salience of COVID-19 health risks may be a relevant factor in people’s mental reactions to the pandemic. First, people who belong to high-risk groups are more negatively affected by the pandemic than those who are not [

13,

16,

25,

26]. Second, people with prior mental or physical health problems experience more mental repercussions than those in good health [

11,

12,

14,

18,

22,

24,

25,

27,

29,

30]. Third, people who know of COVID-19 infections or quarantines in their immediate environment are more affected than those who do not [

18,

23,

29,

32]. Fourth, people with certain symptoms (myalgia, dizziness, coryza) are more affected than people without such symptoms [

11].

Research also suggests that the conglomerate of living conditions, relationships, lifestyle, and media use affects people’s mental response to the pandemic. People’s household composition and social network may give them the social support that reduces the impact of COVID-19 on their mental health and well-being [

19,

21,

23,

25,

28]. On the other hand, household composition may have detrimental effects, caused by interpersonal tensions [

19] or extra worries when living with dependent seniors [

21,

28], children below 18 [

17], or children working outside [

18]. Two studies found that people living in rural areas are more vulnerable to mental health problems than people living in urban areas [

22,

23]. Furthermore, a larger house [

22], a healthy working environment [

19,

21,

22], spending time outdoors [

22], social activities [

19,

33], keeping a daily routine [

30], and physical exercise [

30,

31,

34] appear to alleviate the mental burden of the pandemic. Immoderate social media exposure [

24,

26] and alcohol abuse [

27] were found to have detrimental effects.

Various psychological traits have been connected to the effects of COVID-19 on mental health and well-being. On the positive side, risk tolerance [

15], optimism [

13,

15], forward-looking coping strategies [

25], flexibility [

28], resilience [

29,

36], positive reframing [

30], openness [

35], and dispositional hope [

35] are traits that help people to limit the adverse effects of COVID-19. On the negative side, trait anxiety [

15], negative affect [

18], detachment [

18], negative attention bias [

19], rumination [

19,

25], avoidant coping behavior [

28], anxious attachment [

29], and extraversion and neuroticism [

35] are traits that worsen the effects of COVID-19 on mental health and well-being.

1.3. The Need for More Comprehensive Approaches to the COVID-19 Pandemic Effects

Many of the earlier studies on the effects of COVID-19 seem to adopt straightforward cause-effect approaches, with the emergence or development of the virus as the cause and people’s mental health or well-being as the effect. However, the COVID-19 developments are likely to bring about many different personal perceptions at the same time, not only of the virus and its health risks but, for instance, also of the way it is handled in society. To make sense of people’s mental health and well-being during the pandemic, it is important to examine which of the myriad of perceptions relate to mental health or well-being. Earlier research by Jia et al. [

13] found that adding such perceptions (which they labeled as “modifiable factors”) leads to a drastically higher percentage of explained variance (in their case from 7–14% to 57%).

Reviewing the literature about the effects of COVID-19, we distinguish four layers in people’s perceptions of and experiences with the pandemic (

Figure 1). At the core is the COVID-19 virus itself. Largely based on media reports and discussions with others, people form an idea of the dangers of the virus. Some earlier studies found that fear of the virus (sometimes operationalized in terms of perceived severity and perceived contagiousness) may play a significant role in people’s mental health and well-being [

13,

19]. This aligns with the abovementioned personal characteristic of risk salience. However, both studies were conducted in the early phases of the pandemic. It is imaginable that people’s risk perception decreases over time due to a process of habituation [

50].

However, the impact COVID-19 has on people involves more than its medical consequences. Governments worldwide took drastic measures to contain the virus, limiting people’s freedom and affecting daily life in many respects. Companies struggle to survive and concerns about immediate and long-term economic effects of the pandemic are omnipresent [

2,

3]. Therefore, the second layer involves the impact COVID-19 plus the government measures have on people’s lives. Earlier research particularly addressed three such factors: (1) economic consequences, including job insecurity and financial concerns [

26,

30,

31,

51], (2) social isolation and loneliness [

33,

52,

53,

54], and (3) disruptions of normal life (“liveliness”) and opportunities [

26,

30,

32].

The third layer involves the societal dynamics that the pandemic and the government measures incite. The aforementioned rise of anti-Asian racism would be a clear example of that [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. More recently, conspiracy theories, social unrest, and riots are other examples within this layer.

To conclude, the fourth layer involves people’s monitoring of the effectiveness of the strategies used to find a way out of the pandemic. Earlier research suggested that public trust in the government [

55], trust in doctors [

56], and accurate health information [

11,

56] have a positive relation with mental health and well-being. Similarly, hope (as opposed to hopelessness) was found to play a role in people’s mental response to the pandemic [

30,

33].

1.4. Mental Health and Well-Being

Though not as long and established as research into physical health, research on mental health and well-being is a well-established field of academic research. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” [

57]. With this broad definition, the WHO made a strong connection between mental health and (psychological or subjective) well-being and moved away from earlier (limited) views on mental health as the absence of mental illness or problems. Research suggests that the concepts of mental health, well-being, happiness, and quality of life are closely related [

58]. Several short overall measures of mental health or well-being have been proposed and tested in the literature [

59,

60,

61].

However, given the comprehensiveness of the aspects covered by definitions of mental health and well-being, several differentiations within the concept have also been used. A typology of mental well-being, along with a rich vocabulary of affective states, was developed using the two orthogonal axes of arousal and pleasure [

62]. Distinctions have been proposed between affective well-being (the presence or absence of positive or negative affect) and cognitive well-being (the cognitive evaluation of life) [

63] and between hedonic well-being (focusing on happiness) and eudaimonic well-being (focusing on meaning and self-realization) [

64]. These studies suggest that different views on mental health and well-being might have different antecedents. In our study, however, we focused on an overall conception of well-being, leaving possible differentiations of well-being for future research endeavors.

An important research line in well-being studies involves effects of life events on people’s well-being. Life events may be personal (e.g., marriage, divorce, death of a loved one, unemployment) or collective (e.g., natural disasters). Many studies confirmed relations between life events and people’s degree of well-being, although the relation is often not as simple and straightforward as might be expected [

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]. Different life events may have effects on different aspects of well-being and trait characteristics play a role in the way people react to such events. The COVID-19 pandemic is a clear example of a collective life event, which triggered many health and well-being scholars to conduct research.

1.5. Present Study

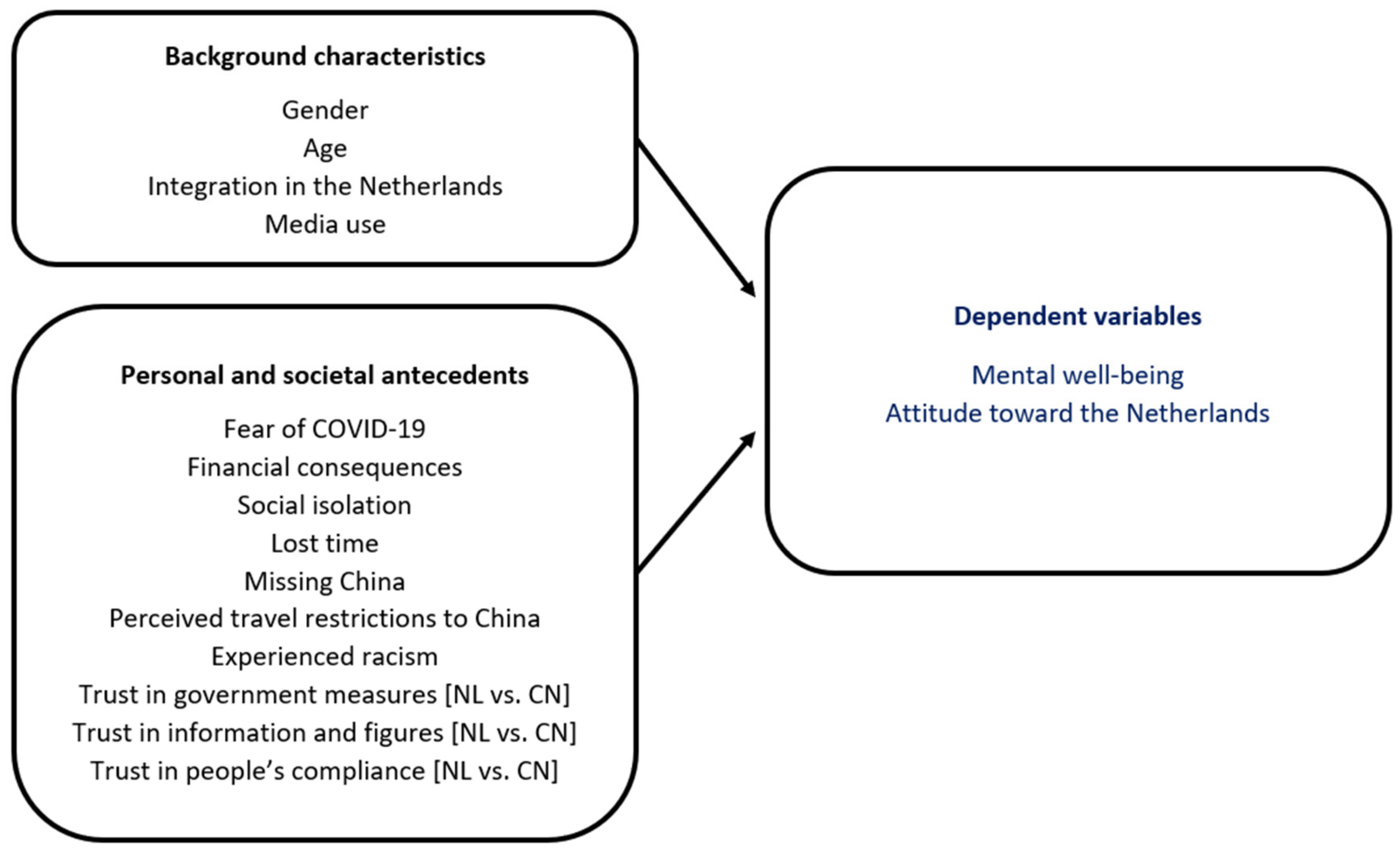

To investigate Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of and experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted an online survey during the second wave of the pandemic (November–December 2020) among Chinese immigrants living in the Netherlands. Our research question was: What are the personal and societal antecedents of the mental well-being of Chinese immigrants living in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic? We focused on two dependent variables: (1) Chinese immigrants’ perceived decrease of mental well-being (the perceived change in position on the continuum between depression and happiness since the start of COVID-19), and (2) their attitude toward the Netherlands (the perceived change in their personal relation with their host country since the start of COVID-19).

The antecedents included in our study covered all four layers depicted in

Figure 1. In the first layer, we measured fear of COVID-19 (the extent to which participants saw COVID-19 as an imminent threat to their personal health). In the second layer, we included financial consequences (the extent to which participants worried about their financial position due to COVID-19), social isolation (the extent to which participants felt that COVID-19 hindered their social life), and lost time (the extent to which participants felt that COVID-19 messed up valuable time of their lives). Specifically from the Chinese perspective, we added two additional variables: missing China (the extent to which participants felt homesick for their mother country) and perceived travel restrictions to China (the extent to which participants thought that COVID-19 made it impossible for them to travel to China within reasonable time). In the third layer, we measured experienced racism (the extent to which participants experienced an increase in racism and discrimination since COVID-19 broke out). In the fourth layer, we measured trust in various aspects of the way the pandemic was handled, both in the Netherlands and in China. Specifically the questions involved (a) the government measures, (b) the quality and accuracy of public information and official figures, and (c) people’s compliance with the measures.

Figure 2 gives an overview of the research model.

Our results confirmed the relevance of all constructs in

Figure 2 for the way Chinese immigrants make sense of the COVID-19 crisis. Furthermore, they made clear that Chinese immigrants are very critical of the Dutch way of handling the pandemic. An analysis of the antecedents of the two dependent variables shows that different combinations of antecedents from the second, third, and fourth layer in

Figure 1 relate to the two dependent variables. Fear of COVID-19 did not significantly relate to either dependent variable.