1. Introduction

Indigenous mobility in Latin America has been approached in much of the research on the subject from the standpoint of migratory phenomena [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Such research emphasizes aspects related to inter-censual migratory variations, underlying reasons for such variations, and the historical, political, and social conditions and contexts that different ethnic groups have had to face in such processes [

5]. Within this tendency, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean identifies two types of Indigenous mobility that have persisted in Latin America: international migration between national states, and local-ancestral migration, which occurs close to the ancestral centers of historic Indigenous settlements [

4].

However, in this article we suggest that, while the examination of Indigenous migration process has provided a solid framework regarding population dynamics, the analysis of other important geographical elements of Indigenous mobility in Latin America has been cast aside. Mobility practices have not been studied much at a Latin American level [

1,

6], despite—as we will argue—often representing processes and spaces for disputes and cultural and political resistance that are important in understanding the intercultural dimension that characterizes Latin America. In this intercultural context, we find the case of the Aymara ethnic group in the far north of Chile.

As we will suggest, the case of the Aymara people of northern Chile is connected to processes of ancestral territorial mobility. As in other Indigenous groups in Latin America, Aymara mobility practices imply spatiotemporal dynamics that are key for the dynamic construction of place. These mobility practices have, however, changed in recent decades. This is explained on one hand by intensive urbanization and rural–urban migration processes in Latin America from the second half of the 20th century, and by significant changes in the political–economic order that occurred within the consolidation of neoliberal model since the Washington Consensus in the 1980s and which emerged as expressions of the prevailing hegemonic vision and policy of progress of the Chilean State [

7].

It is, however, worth mentioning that the role of the state in mobility and in Aymara territories goes back a long way. Since the present-day region of Arica and Parinacota in the extreme north became part of the administrative political boundaries of Chile at the end of the 19th century, a process of homogenization called “Chileanization” was carried out, which was characterized by “a network of police, tax, educational, health, political and legal control systems” [

7] (p. 120). This process lasted for more than a century and has not only affected the Aymara people, but also other Indigenous groups. For example, the process of “Pacification of The Araucanía” at the end of the nineteenth century, the Republic of Chile subdued the Mapuche population, taking over the most prosperous agricultural valleys, establishing cities, and installing a set of hegemonic cultural and economic policies that have maintained these two cultures in political and territorial conflict to this day. This process displaced thousands of Mapuche from their lands, forcefully creating mobility and migration processes as they sought refuge in the foothills of the Andes [

7].

On the other hand, Aymara mobility processes are also explained in cultural terms of the Aymara groups themselves. Throughout the history of what is now the region of Arica and Parinacota in northern Chile, the Aymara people have inhabited the land through mobility. While such mobility has experienced changes over the years, it remains as a constant expression of territorial dynamics. Mobility flows have left both material and immaterial traces that have condensed along the routes utilized over time, as well as in the various places connected by these routes. Such traces can also be found in the collective and individual experiences of those who incarnate this mobility in varying ways, throughout the life stages of the Aymara inhabitants of the territory. Aymara mobility has thus been an important aspect in the configuration of a dynamic cultural grid in space and time, with a unique capacity to adapt and face the territorial and political-economic transformations of recent decades.

In an intense urbanization process, the migratory process of highland and low-lying mountain peoples towards valleys and coastal cities began in the mid-20th century [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. This process became an intrinsic characteristic of Aymara mobility, representing a new action framework that gave way to other dynamics that implied periods of permanent residence in the city of Arica [

13]. Changes in the means of transportation and the reasons that motivated mobility provided the impetus for this process, influenced by factors such as the attraction to the coast and valleys due to the installation of industry, work, and continued education opportunities, and the development of commercial and exploitative activities in the Lluta and Azapa valleys [

14]. All of this occurred under the political auspices of “ideological pressures based on a Chilean vision of progress, national identity and civilization” [

7] (p. 129).

However, as these mobility processes occurred in areas around the ancestral centers of historic Aymara settlements [

15], we suggest that new means of rural-urban mobility were configured and older ones were reactivated; specific movements from the urban coastal areas to the high mountain areas, as well as the cultural reterritorialization that has contributed to processes of symbolic mobility. The latter has led to several changes to rural populations and to the urban areas that receive these movements, as well as along the routes between these places. These changes, in turn, led to transformations in the ways of inhabiting the territory, life experiences and Indigenous territorialities [

13].

Such changes have reinforced mobility as an essential dimension in Aymara territorial construction, as it crosscuts and interconnects with social, political, economic, and cultural dimensions. In recent decades this has led to Aymara mobility being the subject of various studies that have documented, described, and/or theorized issues such as migratory movements, adaptive strategies, urban-rural articulation, regional integration patterns, and construction and transformation of Aymara space, among others [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

16,

17]. While such research has provided a solid framework regarding internal migratory processes, the practices and meanings associated with mobility, and their cultural and political implications, have been largely left aside.

Cresswell [

18] (p. 20) defines mobility as the intertwining of three aspects: physical movement; the representations of movement that provide shared meaning; and practices of movement. Together, these three aspects condense the experiences and the incarnation of mobility. These aspects of mobility are also political, as they express and produce power relations [

18]. This implies that “mobility is not merely a reflection of social structures, which is to say that it only reproduces such structures, but rather it actually produces these differences” [

19] (p. 1).

Therefore, this article articulates Aymara spatial-temporal practices with elements of the new mobility paradigm, contributing both to the comprehension of Aymara mobility and a widening of the new mobility paradigm based on Indigenous and inter-cultural contexts.

The new mobility paradigm [

20] allows for a more holistic understanding of Aymara mobility by expanding the analytical framework. This is to say, by transcending a conceptualization focused solely on movement between two points, to include the experiences along the route and the transportation of cultural expressions, emotions and the spatial imaginaries of the subjects. We propose that the latter, in terms of mobile actors, both connects places that dialogue with each other, and composes a translocal linkage; a linkage in which the rural and the urban are intertwined through various dynamics, connections and interdependencies [

21]. Therefore, it is not only the bodies of the subjects that move, but their emotions, culture, and memories as well.

On the other hand, it is important to be able to go a step further regarding mobility, combining the conceptualization and methodological approach of the new mobility paradigm with Indigenous practices and experiences. Such experiences have had mobility as a central axis of their social, cultural, and economic dynamics. Based on the spatiotemporal analysis of the mobility of Aymara groups, contributions can be made to research on the new mobility paradigm. This is important, as the new mobility paradigm has not had much connection to intercultural and Indigenous contexts. For this reason, we propose that Aymara mobility practices and meanings imply particularities that make spatiotemporal heterogeneity and contraction more sophisticated [

22] in terms of the construction and experience of mobility. In turn, in agreement with Cresswell [

18] we propose that Aymara mobility is expressing and politically revindicating itself against hegemonic power relations that have made their culture invisible for decades.

This study takes the migratory processes that began in the 1950s as a point of reference. This process led to the majority of the Aymara population coming to live in the city of Arica, which concentrates 97.9% of the total population of the region [

23]. Based on the elements of mobility established by Cresswell [

18], the objective of the study is to research the meanings and practices associated with urban-rural mobility in the experience of Aymara people who migrated from Putre to Arica during the 1950s.

The article is structured in four sections. First, it establishes the theoretical approaches to the new mobility paradigm, the role of mobility in the construction of place, and Aymara mobility. The second section deals with the localization of the study and the methods used. The third and fourth sections are developed based on the current practices and meanings associated with both old and current mobility, in terms of both physical and symbolic movements, approached through the idea of accumulative traces.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Shift towards Mobility

In recent decades, mobility has taken on renewed relevance through the growing body of work of different disciplines and areas of research, such as geography, sociology, anthropology, and archeology, among others. Such work has involved the emergence of new research perspectives from the social sciences [

18,

19,

20,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

The centrality that mobility has achieved is based on what some authors call the “shift towards mobility” [

18,

20]. This has generated an interdisciplinary shift that has facilitated the incorporation of a “transformational outlook on socio-spatial research” [

30] (p. 58) and transcended “the dichotomy between research on transportation and social studies, placing a [focus on] the social relations [developed] during movement and connecting different ways of transportation with complex patterns of social experiences” [

20] (p. 208). This is what Sheller and Urry [

20] call the new mobility paradigm, which points towards a more holistic comprehension of mobility.

For Sheller [

28], this “paradigm” involves research on subjects’ movements, objects, and information in dynamic relationships, emphasizing the connection between mobility and immobility, and including the practices, representations, ideologies, and meanings incorporated into both.

Cresswell [

18] (p. 18) distinguishes something new in the way that mobilities are being approached by this nascent perspective, in that they transcend certain classic views that have generally conceptualized mobility from a more quantitative perspective, considering “time in transit as dead time”. As an example, Cresswell points to the theory of migration, in which movement is understood based on the expulsion-attraction dynamic in which one place expels people and another attracts them. In this way, despite an apparent focus on mobility, migration in the traditional sense is much more related to place than mobility.

According to Jirón and Mansilla [

30] (p. 58), these traditional views of mobility connected to certain disciplines such as geography or transport engineering, “have studied only the material dimension of movement, in terms of the structural patterns, leaving the conditions that emerge as a result of the experience and those that are experienced by people during movements aside”. Sheller and Urry [

20] (p. 208) profess a similar view on this point, indicating “travel has been for the social sciences seen as a black box, a neutral set of technologies and processes”.

As such, this new focus widens the perspective of mobility, including various aspects such as experiences, practices, modes, and elements that are in movement, which in turn transit through various scales from the body on up to the entire world [

31].

For this research, we have considered Cresswell’s [

18] definition of mobility, which points towards the intertwining of three aspects:

physical movement, in terms of movement between one point and another;

representations that allude to meanings that are constituted through narratives associated with mobility; and

mobility practices, which represent simultaneously a sense of specific, daily practices such as walking, and a more theoretical sense of social elements, in which such experiences are framed. Related to these aspects, Cresswell mentions different forms of mobility (driving, flying walking, etc.), which “have a physical reality, they are encoded culturally and socially, and they are experienced through practice” [

18] (p. 20).

2.2. The Role of Mobility in the Construction of Places

The shift towards mobility has also led to places being conceived more in terms of fluidity, rather than the traditional basis as nodes of immobility [

29]. This led to a problematization regarding opposition between notions of mobility and immobility. This can be seen, for example, through work on rural-urban connections by Hedberg and do Carmo [

32], which indicates that mobility cannot be defined in opposition to the notion of immobility or a fixed state. Using a translocal perspective, these authors identify spatial mobility as a primary element within their analysis, conceiving it as a way to connect and produce places. The latter are understood from a dynamic perspective, considering places as relational and interconnected, constructed by their interrelations with other places and in constant transformation through these interrelations [

32].

Along these same lines, Lindón [

33] (p. 9) proposes that relational place “remains completely connected to the logic of movements as a constant tension between permanence and change, which in turn can operate on differing temporal and spatial scales”. Cresswell [

18] points out that place is in a constant state of transformation, correlating with Massey [

34] (p. 79), who indicates that place is an “open node of relations; a connection, an intertwining of flows, influences and exchanges”, and that it must be approached as a constellation of processes [

22].

In this way, mobility is “just as central to human experience of the world as place” [

25] (p. 3), providing certain anchors that are also integral to place itself. Beyond movement between one point and another, places and the processes for their construction represent important components of mobilities [

29,

35]. For Urry [

36] (p. 269), “places are economically, politically and culturally produced through the multiple mobilities of people, but also of capital, objects, signs and information”.

As such, places are understood as particular nodes that are in constant construction, and are defined by meanings, stories, and practices associated with being in a certain space, “inseparable from the experience, thoughts and feelings of those who inhabit them” [

37] (p. 80), and being in or beyond a specific geographical location [

38].

In this sense, places of ‘origin’ and ‘destination’ are important, as is the place in which the movement takes place, as the trip also has its place. It is not enough to merely focus on exit points and points of arrival; the experiences of movement between points is very significant as well [

39]. For this reason, “arriving is important but so are the stories woven around the travelling” [

40] (p. 84). The latter actually compose the experiences of place, and are transformed by individual biographies as “polysemic, contextual, processual and biographical” [

24] (p. 79).

2.3. Mobility in Inter-Cultural Contexts: Aymara Mobility

Research on Aymara mobility has focused mainly on internal migration, and dates back to as early as the 1980s [

8]. Such work has continued to this day, as part of an important area of research that deals with regional dynamics in the Tarapacá and Arica and Parinacota regions of Chile [

9,

10,

11,

12,

16,

41,

42]. In this context, Carrasco and González [

12] (p. 220) utilize the term “mobility of the Indigenous population”, as a notion that facilitates comprehension of “country-to-city migration, questioning the traditional, unidirectional approach [

43] and widening the focus to a practice in which there is a constant flow and reflux of people within the same rural sector, as well as between these sectors and urban areas”. In this way, the concept of translocality has been integrated into the local level, through research on migratory phenomena and regional mobility [

9,

10,

11,

12,

14]. Here, the use of the translocal implies the idea that the Aymara community is no longer circumscribed to a locality, but rather enjoys continuity spread widely throughout the regional territory. Within this territorial expanse, there is a simultaneous influence from the rural sectors to the urban areas and vice versa, or in “more fluid social spaces, with malleable borders and in constant transformation” [

9] (p. 108).

It is proposed that the internal migrations that have occurred throughout the past seventy years in the region have given way to the construction of translocal networks and relations that manifest themselves in the rural-urban space. This is expressed, for example, by the fact that many of the Aymara that settled in the city maintain connections with their localities of origin through participation in religious festivities and celebrations (such as carnival or patron saint celebrations), or as members of local organizations (such as neighborhood groups, rural producer groups, or Indigenous community groups). At times they represent their community in Arica and at others they go back to their towns for the more important local meetings. Individuals from the same locality also tend to meet around certain spaces of social reference that have been created in the city, such as the so-called “Sons of Nations” centers, or other organizations formed under the auspices of Indigenous peoples (native dances, sports clubs, and elders organizations, among others) [

11].

This has led to the consolidation of significant precedents on the subject and a wealth of research work on migratory processes. However, the predominate perspective regarding mobility is still that of human displacement, leaving experiences en route and associated meanings to a secondary role. The appearance of other forms of mobility (such as symbolic mobility) has also been relegated to a secondary role within the research. Such mobility could be considered as “indirect mobility” [

38], which is related to the cultural reterritorialization of the city and movements of memory.

This more comprehensive form of understanding mobility allows us to examine the political role of mobility in terms of Indigenous resistance, ethnic revindication, and territorial dispute [

44,

45]. We will argue that the translocal mobility of Aymara people in the current urbanized era is also an act of cultural and political self-determination [

7]. As such, we propose that mobility deals not only with subjects, but with cultural, symbolic, and political elements as well. Whether it is physical or symbolic, mobility has been fundamental to processes of re-territorialization, and thus to the construction of Aymara places.

All of these characteristics thus broaden the understanding of Aymara indigenous mobility and place it in a relevant space of claims and legacies, considering the historical context where they have occurred, that is, within territories that have experienced great transformations and conquests since the pre-Hispanic era, the colonial period and the establishment of Nation States, with their hegemonic ideologies and their political-administrative boundaries.

3. Area of Research and Methodological Approach

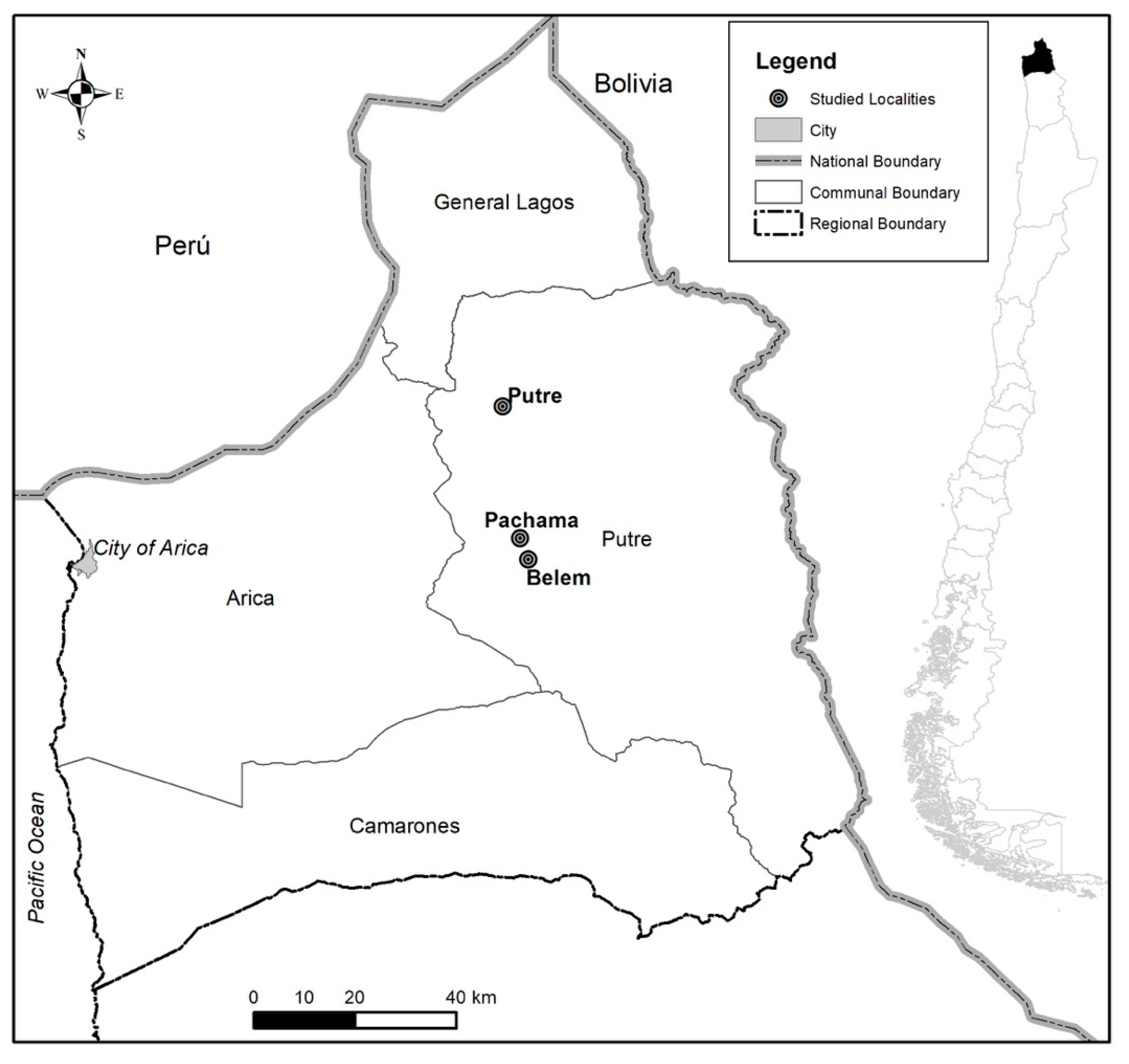

The research was carried out in Arica and Putre, in the Arica and Parinacota region, located in the extreme north of Chile (

Figure 1), and which borders both Peru and Bolivia. The entire area along and around the borders between the three countries represent part of the ancestral center of Aymara settlements, which existed prior to the establishment of modern nation states.

According to the latest census of Chile (2017) [

23], the region has a population of 226,068 inhabitants, of which 97.9% reside in the municipality of Arica, and 1.2% in Putre. In this way, the population is mostly urban (91.7%) to a higher degree than the national average (87.8%), concentrated mainly in the largest urban center, the city of Arica. On the other hand, Arica and Parinacota is the region with the highest percentage of the resident population identifying as belonging to an Indigenous group: 36% of the population identifies as belonging to some Indigenous group, in which the Aymara ethnicity predominates at 75.3%.

One of the conditions that has had profound effects on the distribution of human settlements, mobility, social, productive, and cultural dynamics is the geomorphology of the region. This is made up of areas differentiated by altitude: the coastal plains (city of Arica); the coastal mountain range (to the south of Arica); the intermediate depression (ravines and pampas); and low-lying mountains and the Andes mountain range (the altiplano). For this study, we moved from the coastal plains in the city of Arica, to the towns of the low-lying mountains of Putre, located at altitudes of 2500–4000 m.

Methodologically, this study is framed within a research process that began in 2014. This process has been approached from an ethnographic perspective, combining various techniques such as semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and mobile accompaniment [

35,

46,

47,

48]. The overall purpose of the research has been to complement the collection of information that would allow for a broader analysis of mobility, based on the primary places of residence and in situ movements.

The fieldwork was carried out between 2014 and 2020, mainly in the city of Arica and the town of Putre, both in the Arica and Parinacota region of Chile. Exceptionally, researchers also traveled to the town of Pachama, in the same region. During the fieldwork, information-collecting methodologies were applied, including participant observation of certain patron saint festivals and other local celebrations, and 30 semi-structured interviews were performed with key informants such as subjects who were born in the towns of Socoroma, Pachama, Parinacota, Putre, Guallatire, Chapiquiña, and Belén. These subjects had migrated to Arica starting in the 1950s, and were contacted through snowball sampling.

On the other hand, the mobile accompaniments (N22) were recorded by field notes, and were carried out during trips on public transportation along international highway 11-CH, and then on Route A-147 that connects Arica with Putre. Such accompaniments were also performed using private mobilization between Arica and Pachama, by Route 11-CH, and then using Routes A-31 and A-153 (see

Figure 2). The data collected from both methods was integrally analyzed using the content analysis technique [

49,

50].

4. Mobility as Accumulative Traces: Current Outlooks on Practices and Meanings Associated to Other Movements

“In my mountains, just by looking at a physical space

I am transported to the past.”

(Man, 69 years old, born in Pachama)

In order to understand mobilities of the present it is necessary to take a good look at mobilities of the past. Interviewers employed this strategy while accompanying subjects on their travel routes. These mobile accompaniments were used to identify landmarks, memories, and keys to urban–rural Aymara mobility. Based on this information, it was possible to observe how mobility today is constructed and imbued with meaning through accumulative territorial traces that are characterized by both material and immaterial elements condensed into the landscape.

These elements appeared in different ways along the routes between Arica and the low-lying mountains, where the subjects’ towns of origin were located. One of them was reference to old modes of mobilization, such as walking paths and drover roads, traveling by horse, train, or truck. The latter imply a significant symbolic importance, in that trucks were the first motorized mode of transport that reached the hinterlands, following the construction of roads in the 1960s. In addition, this was the mode of transport that most of the interviewees had first used to get to the city, and which allowed them to return to their towns of origin in the first few years after moving.

Another common theme in the stories related by the interviewees was past trips as an essential means of survival in the highland and low-lying mountain areas. In this context, mobility became a need, through family commercial strategies for the trade of products between Arica, the mountain towns, and Bolivia.

At the same time, mobility experienced before having moved to the city maintains a certain meaning in the present. Such meanings could be as communication with other places; a mechanism to resolve basic needs; to facilitate family work in cases when animals and provisions for the journey had to be arranged days before the trip; to elicit emotions due to the return of parents or grandparents, bringing news, anecdotes and familiar products; and as a space to facilitate mutual support, because journeys were generally made in groups. Mobility is also connected to absence, for those who remained in towns did so in a constant state of waiting and expectation.

These experiences, inscribed as part of a way of life that is predominately present in collective memory [

51,

52], emerged organically through the stories localized within the city and along the routes taken, such as the international highway and its adjacent roads. Constant reference was made to mule driving, family, places for planting and cultivation, and the interconnected local life.

At the same time, all interviewees maintain vivid memories of their first trips to Arica, including who they travelled with, the routes they had to take, the waiting, the modes of transport, the clothes they wore, especially being hungry or cold, the emotions they felt in leaving their towns and moving to the city. This lived experience, as a mobility practice, has constructed the direct experiences of place. These experiences have been anchored in landscapes as well as in memory, making up part of the accumulative traces that construct the territory itself.

The main motives that triggered the decision to leave towns of origin were related to having a different perspective on life. In most cases, this was represented by expectations of improving the family economy through work and continuing formal education, as in most rural towns schools only taught to 6th grade. Despite the apparent freedom with which they made the decision to migrate, due mainly to the idea of mobility as a means to progress in life, there was also a political-historical context, which in a way forced their mobility. The role of this context is very clear in the production of power relations and dynamics of domination [

18], through the creation of inequalities and exclusion by state policies.

In this way, the process of mobility experienced from the 1950s can be constructed as a fundamental landmark in the life experiences of the interviewees; both those who migrated alone and those who travelled as a family to live in the city. In addition, other elements were also transferred together with the actual people, such as traditions, customs, emotions, and practices. For this reason, mobility not only represented human displacement, but also all of these other aspects together, and which are today key in terms of ethnic revindication in territorial urbanization processes.

Moving to Arica as a permanent place of residence meant the end of a stage characterized by a traditional way of life in relation to their primary, nuclear family. This way of life was connected to agrarian cycles around their localities, and rotation between different localities (due to crops, school, or other reasons). It also implied the beginning of another stage, related to consolidating complex connections between places and times through their own movements, and processes of symbolic mobility.

This urbanization process of Aymara groups involves a highly political process of mobility. Adaptation to the city was a difficult process for many of the interviewees, who were children at the time. Beyond the family boundaries of the town, the city lengthened both the physical and symbolic distance from the known, and hegemonically denied and made invisible Aymara cultural traditions. In this context of denial, the mobility between the city and the places of origin was expressed due to deep yearnings and nostalgia for the family, localities, climate, and the ways of life that affected memory.

This also demonstrates the role of mobility in the production of social differences through the implementation of educational public policies. Limited access to education in towns in the hinterlands, which made up a significant part of the reasoning of most of the interviewees for moving to the city, represented a serious violation of children’s rights by the state. In many cases, though mothers and fathers decided to send their children to the city, it was the state that politically forced this displacement, necessary to achieve higher levels of education. This exposes the lack of protection for children who did not have the tools or the maturity needed to perform beyond their primary family circle. In addition, in the midst of the “Chilenization” process (the process by which, through different means of control, including public education and obligatory military service, the state imposed the deliberate elimination of all cultural traits of the Aymara population), school was not a safe space for children, as many were discriminated against for having certain physical, linguistic, and cultural traits.

In this context of becoming culturally invisible, reconnecting to their towns of origin was especially important for Aymara people, though the frequencies of these trips were irregular and were established according to the specific dates of summer and winter vacations, as well as the economic feasibility of making the trip.

As several people told us, the conditions in which these trips were made—the poor condition of roads, the shortage of public transport and the long journey times—did not change for decades, and government authorities showed little interest in improving them, this being an important political aspect in mobility. Despite these adversities, the temporary return to the locality was constituted as a desire to reunite with the maternal, paternal, and community affections, reinforcing the town as a space of protection and belonging. Therefore, these trips that connected the city with the rural towns of origin not only had a resignification in topophilic terms [

53] from new practices and meanings of mobility, but also were fertile ground for the emergence of expressions of local and ethnic revindication in an intercultural context.

Thus, mobility movements, practices, and meanings have been constituted in a localized way through these accumulative traces that contain ways of inhabiting the territory. These traces have an effect on the construction of place in accordance with political-historic contexts and the biographical experiences of the interviewees.

5. Present Mobility as Construction of Place and Cultural Revindication

Despite the strong ties with their localities, none of the interviewees ever definitively returned to live in the low-lying mountains or altiplano again. The primary reasons for this were the formation of their own nuclear families in the city, and that the rural towns had very few or no job opportunities for electricians, accountants, secretaries, tailors, factory workers, or domestic workers, nor were there many services or industries; some did not even have electricity.

These reasons were intrinsic in the construction of a place with an emotional base in Arica. In forming this place, the emergence of social and community spaces related to towns of origin was also an intrinsic factor. To this day, such spaces continue to be built based on networks of people from one or more towns. In this way, different cultural and local expressions have been reterritorialized in the city, configuring a spatial tapestry of cultural revindication. Although for several decades these spaces were only developed through intimate social circles, over time they expanded, first through food and the Andean football league, and then through music and dance (

Figure 3). These spaces now play a very important role, and are constituted as spaces that mark a strong reference in terms of their ethnic identity, origins, and culture.

These anchors—culturally significant and politically revindicating—have deepened the interdependencies between the city and the towns of origin in the highlands. Physical and symbolic mobility are expressed based on the trips by the interviewees to their towns of origin, and by the mobilizing role of memory, tradition, and customs in the spaces of reference in Arica. Over time, this process has been constituted into what is referred to as “making” a town in the city, coming to include newer Aymara generations that were born in Arica. Thus, indirect symbolic mobility is practiced constantly through group associations, socio-political demonstration, music, dance, food, celebrations, and memories that trigger individual and group nostalgia. At the same time, such shared elements produce cultural reproduction, ethnic identification and emotions connected to a native land. Therefore, a place of belonging and memory is constituted as a, “container of meanings [that] emerge from deeper experiences that have accumulated over time” [

54] (p. 197). Such places concentrate traces of meanings that are spatialized, connecting emotions, histories and experiences that reference past, present, and future human communities.

All of this also accounts for the political role of mobility in terms of resistance and territorial dispute, especially in symbolic terms. In this sense, the strong ideological pressures embedded in state policies that led to an apparently voluntary displacement from which cultural assimilation processes were promoted gave rise to and accommodated cultural expressions that over time generated counterbalances and made space, through moving bodies and memories, for affection for the place of birth and for the place of principal residency, demonstrating a translocal realization and revindication of place, i.e., a spatio-temporal act of self-determination. The same city that made this culture invisible for decades is used today by Aymara groups as a platform for resistance and revindication of cultural traditions, which are expressed in various types of socio-political and cultural activities. However, these urban activities are spatio-temporally connected with other manifestations that the same Aymara groups that today live of Arica still carry out in their towns of origin in the Altiplano (

Figure 4).

The intertwining forms of physical and symbolic movement corroborates the idea that movement from one point to another is only one dimension of mobility. Mobility occurs on several scales, from regional to corporal, composed of experiences imbued with meaning that traverse subjects and connects them with various times in history. These experiences are incarnated within the relational places in Arica, their towns of origin, and the routes taken between the two. The trips by the interviewees to their towns of origin reinforces the aforementioned idea of accumulative traces, which are reflected along the routes, and where current practices of urban-rural mobility that include modes of mobilization and experiences along the way, are constituted by memories and aspects of daily life:

“Around here we took the animals to pasture with my cousin” (Woman, 71 years old, born in Chapiquiña);

“In the rainy season so much water came down that the trucks couldn’t pass, and here we would wait for the water to go down a little to be able get by on horse” (Woman, 64 years old, born in Putre);

“Here the truck got stuck, and we got down with a shovel to dig it out of the mud” (Woman, 72 years old, born in Putre);

“Before that road went to Arica” (Man, 66 years old, born in Chapiquiña);

“My grandparents used to plant crops on that hill” (Man, 69 years old, born in Pachama);

“From this point on I usually sleep” (Woman, 76 years old, born in Putre);

“I was afraid to travel with the trucks because the road was bad, there were a lot of rocks, holes, sometimes the brakes would go out and the trucks flipped over (…) but today the road is paved” (Woman, 72 years old, born in Putre);

“Here in Zapahuira we always have breakfast” (Woman, 44 years old, born in Parinacota);

“On the road sometimes I talk to people I know, sometimes I read the newspaper, sleep, or sometimes I just get bored” (Woman, 72 years old, born in Putre);

“I like to knit on these trips” (Woman, 65 years old, born in Guallatire).

In this way, current mobility practices are made up of memory landmarks and past experiences, as well as by common actions or sensations such as sleeping, getting bored, listening to music, knitting, or talking to the person in the adjacent seat.

Although present mobility continues to be related to the past, it is a mobility that is in constant transformation. Practices, for example, in terms of ways of moving, have changed a lot since the first trips. Walking, riding a horse, or trips in the back of a pick-up truck as a passenger are no longer normal for getting from the city to the towns. These days, public transportation or a private car are more common.

Such changes to the modes of transport have influenced the experiences of travelers along the routes: today the character of these trips is generally dual or collective, as trips are made as a group or a family. It is increasingly rare for someone to travel alone to his or her town of origin (with the exception of work-related trips). This new dynamic is related to the reasons for making the trip and the frequency with which they are made; trips are made with far more planning rather than spontaneously as they used to be, and the time spent generally ranges from just a day to a weekend, depending on the occasion. These changes are also facilitated by a higher degree of access to private means of transport, as most now have and use their own car or a shared vehicle, which allows them to better plan the departure time and travel more comfortably. Some people occasionally use public transport to get to their towns of origin, mainly on meeting days. However, it is important to note that the supply and frequency of transport services are scarce (one or two companies and/or private individuals offer services to each locality), which is also a factor regarding the low use of this mode of transport. In effect, with the exception of the towns of Putre and Socoroma, which have daily transport services from Arica (once a day), most other towns in the low-lying mountains only have such services twice a week (in the case of Belén or Chapiquiña, Tuesday and Friday) (

Figure 5). Such services are even scarcer for certain towns in the altiplano such as Guallatire, which only run once every two weeks.

This scenario reopens the political dimension of mobility: it shows that mobility is a resource with differential access for different users [

18], in which the frequencies, velocities, and comfort levels of journeys vary based on governmental mobility polices and on the economic capacities of travelers. In these regard, mobility experiences of Aymara people “open up significant debates regarding who exactly benefits directly from mobility policies, and how public policies can positively affect the possibilities and conditions of travel for the population” [

35] (p. 258).

Regarding the reasons for physical mobility practices, it can be pointed out that these are cultural, symbolic, and political in nature: the interviewees travel for the celebration of festivals, traditions and costumes; visiting patron saints, family or local farms; attending meetings of territorial organizations and to discuss political issues related to their culture. A few interviewees travel for economic or productive reasons, such as checking on animals or as tourism guides.

The reasons for travelling to the towns are related to the meanings that people connect with them. The towns represent a reunion with their origins, a source of cultural revindication, a trip to the past, the cultivation of present connections, and projections to the future that, in a certain way, provide for communal sustainability regarding their culture and locality.

Thus, the towns are places that represent roots and a sense of belonging fixed in a specific location, while at the same time are also part of people’s very existence. They are like an engine that mobilizes people, connecting to the extended territory through personal and collective experiences located in relational places: “I have always said that the town is a big family, we are all connected (…), we still have roots there, and that’s why we share everything, we are related by that family, we are related culturally, politically and territorially” (Woman, 52 years old, born in Chapiquiña).

In this way, these meanings associated with mobility are related to going back in order to maintain their place, and to not forget their family, cultural, and territorial lineage: “Since I left I have always thought that one ought to contribute to their place of origin, and I think that people make places…I think that my kids ought to contribute to the place where their grandparents are from” (Woman, 54 years old, born in Belén).

All of this shows that memory is mobile and active within this group of Aymara, making them travel both physically and symbolically, constantly constructing place and shared identity. This is because the town and its extension is memory, as well as a space produced by those involved in the struggle, as the same occurs in power dynamics [

55,

56]. Thus, in the memory that is interwoven in space and time by means of mobility, socio-spatial practices are reconfigured as well as a complex network of cultural and political resistance: Indigenous revindication.

This place is also maintained by experiences in Arica, where indirect symbolic mobility is continually practiced through associativity, music, dances, food, celebrations, and memories themselves that trigger individual and group nostalgia and at the same time trigger cultural reproduction, ethnic claims, and affection for their own homeland as a place of belonging and memory.

In this context, despite the changes that state policies and modernization processes have brought about in this territory, Aymara Indigenous mobilities have diversified, concentrating webs of meanings that spatialize and connect emotions, stories and trajectories that refer to past, present, and future human groups. In this sense, as Huiliñir [

57] (p. 11) indicates in the case of the Mapuche people in southern Chile, the landscapes of Indigenous mobilities “involve a continuous process of updating and/or re-elaboration of practices and narratives of the displacements that resist and subvert the effects of the interventions of the state agency in mobility”.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study involved a trip down mobile paths. From the individual to the collective, these trips demonstrate the mobilities of a group of Aymara people from the region of Arica and Parinacota. The work provides evidence of an experience that contributes to the diversity of mobilities in Latin America.

We are very aware that these experiences cannot be extrapolated to the mobility dynamics of the entire Aymara population, and that they demonstrate one form of mobility among many others. However, we believe that this case study in inter-cultural and Indigenous contexts contributes to a more complex perspective on mobility regarding its heterogeneity and the connection of differing temporalities that are physically and symbolically intertwined as key aspects in the configuration of place.

This is precisely one of the main contributions to the new paradigm of mobility: Aymara mobility, as a representation of a “mobility of resistance” in intercultural contexts, crosses and challenges the notion of chronological time. Aymara mobility connects the past and the present through complex intergenerational and embodied transformations and representations of the landscape. This spatiotemporal understanding of inhabiting place though movement questions the traditional approaches to time and mobility; it helps us to generate a more holistic understanding of mobility, from which new epistemologies emerge for its development.

The narratives and references, both those that are localized and those identified en route, demonstrated that mobilities were gestated from the very beginning, based on material, functional and/or forced necessity, as well as emotions, rural ways of life, communication and absence. This then gave way to a diversification of mobility, mainly centered on a symbolic-emotional mobility and, in a way, on another kind of need: spiritual, emotional, and a sense of belonging.

This reaffirms that the mobilities of this group of Aymara are part of and have been constructed by accumulative territorial traces, which are manifested in places that they have made relational through their own actions. These mobilities are connectors to past and present times, through practices and meanings associated with physical and symbolic movements.

In this sense, it is important to point out yet again that these mobilities not only refer to human displacement, but also to other inter-related elements that move, such as culture, memories, emotions, customs, and foods. Considering the complexity of the relations between these elements makes it possible to conceive of extended territory from a different perspective: that of transformative and dynamic mobility, which is necessary for transcending the static categories of ‘rural’ and ‘urban’, and of mobility itself as merely physical movement.

Based on the development of this research, we conclude that these mobility practices and meanings dispute perspectives on territory and place based on experiences. This leads us to consider the political role that such mobility has played in different areas, from the reproduction of inequalities based on access to basic rights such as education or healthcare, to the depopulation of towns in the altiplano and Andes mountains, the creation of referential spaces of a social or ethnic-identity based nature, and the memory of travel and physical travel for reasons ranging from festive to functional, and which allow for the reactivation of the towns. The same was also observed during the mobile accompaniments. Such experiences were part of a “lived” time, full of localized references to the landscape along with songs, conversations between two people or a group of people, spaces of contemplative silence and sleeping, stops for breakfast and scented water for altitude sickness, fear of steep drop-offs and trucks, laughter and varying speeds, all along the way.

In this sense, the experiences of this group of Aymara as a representation of Indigenous mobilities contribute relevant and particular aspects to the new paradigm of mobility, integrating a symbolic and translocal dimension through these cumulative routes that reflect ways of inhabiting, contesting, and building territories. At the same time, they show us how the current processes of cultural and political self-determination are deeply linked to dynamics of mobility.

In a broader sense, this case helps us to expand the theoretical limits of the new mobility paradigm, which has mainly been commanded by Eurocentric perspectives or cases. Current literature in this area has been somewhat disdainful, not yet examining in sufficient depth the ways in which the politics of mobility (in Cresswell’s terms) have made indigenous and minority group worldviews invisible for centuries. Examining more deeply the processes of Indigenous (im)mobility is therefore key to understanding the new paradigm of mobility from the perspective of heterogeneity and difference, and with that really expanding the meaning of what Creswell called the politics of mobility.