Reshaping the Role of Destination Management Organizations: Heritage Promotion through Virtual Enterprises—Case Study: Bresciatourism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cooperation in Tourism

2.2. Virtual Enterprise in a Turbulent Environment

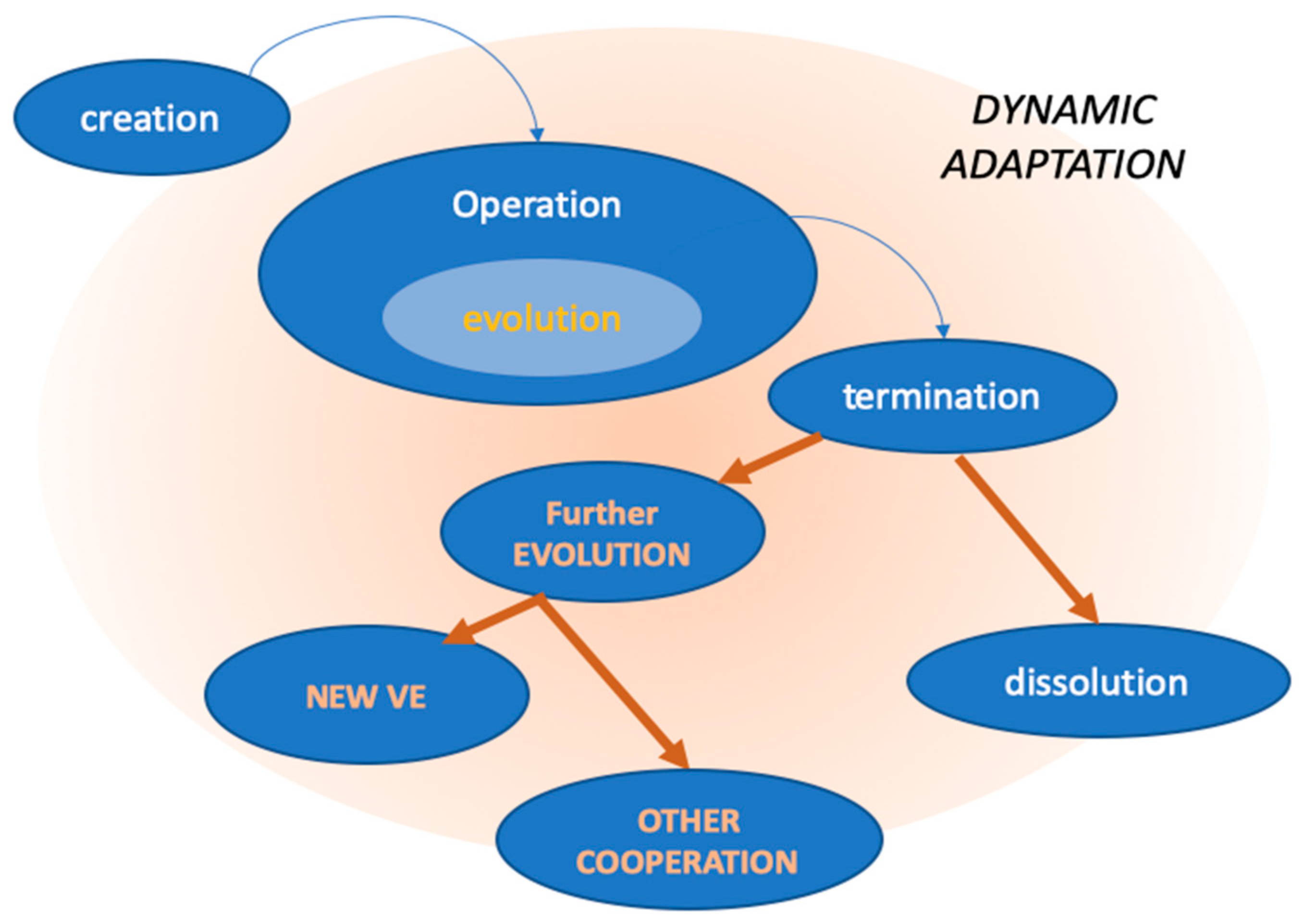

- Establishment: This stage defines and configures the relationship between partners, establishing an initial discussion on the resources and business process interfaces that each participant can devote and the conditions for it (such as security, reliability, authentication, payment and fault tolerance).

- Provision: This represents the operability of the VE.

- Termination: The access rights, interfaces, and implementations of the provided business processes and services can be modified by the VE partners.

3. Methodology

- time;

- resources (to run strategies and activities);

- overlapping activities of the autonomous parties.

4. Case History

- fill the information/communication gap by providing key content in different languages;

- provide better info-promotional content and promote interchanges between local tourism operators;

- attract prospective travelers interested in visiting the province;

- improve awareness of local attractions abroad;

- educate tourists about the rich heritage of the Brescia province;

- support the tourism experience;

- enhance cooperation and communication between local areas of the province;

- increase the touristic and digital skills of the local tourist operators.

4.1. Content and Templates

- art and culture, UNESCO;

- food and wine, itineraries, main events;

- sports;

- environment, protected areas, natural parks, mountains, lakes;

- wellness and health;

- intangible heritage and historical villages;

- religious tourism, itineraries and pilgrimage;

- lifestyle and luxury.

- Follow-up link: In order to enhance content dissemination, each post must contain a direct link to the DMO’s website and/or the partner’s website.

- Hashtags: Hashtags are allowed and recommended. The main one is the official one for Bresciatourism (#visitbrescia), and partners could add their own. A list of suggested hashtags was defined and shared.

- To create the best post to be viewed by potential tourists, each partner was requested to add copyright-free photos or videos about the destination or the event being promoted.

4.2. Timing

4.3. Localizing Content in Different Languages

- The time needed to run a project such as this is huge, but it is reduced when sharing with partners, delegating all of the organizing activities to a head (the DMO), and focusing on the activities each one is in charge of, following the agenda and the due date.

- Resources (to run strategies and activities) are well-defined at the beginning of the project: the DMO is in charge of several activities, while each partner only needs to generate posts and send visual material about their local heritage.

- Overlapping activities of the autonomous parties are quite limited due to the given content, templates and timing.

5. Findings

- agree to devote a defined share of their resources (financial, materials, information, human resources and time) in exchange for mutual improvement and in pursuit of the VEt’s goals.

- plan and develop the project under the coordination of the DMO in such a way that it will be optimally run. Timing is fundamental to plan the temporary cooperation and to achieve the best results from it.

- The DMO should head the VEt and partners should trust and recognize the DMO as crucial.

- Time has a strongly negative association with the VEt: The VEt usually requires a short-term commitment to accomplish the temporary cooperation; moreover, it emerges indirectly through dynamic capabilities and mid-process checks.

- Information and communication technologies support optimum VEt operability, enabling the benefits of the relationship at lower costs. Both the VEt structural system and its operation benefit from strong dependence on ICTs.

- The heritage of the whole destination is promoted through the VEt.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hannam, K. Tourism and Development II: Marketing destinations, experiences and crises. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2004, 4, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, K.; Varvakis, G. Competitive Strategies for Small and Medium Enterprises. Increasing Crisis Resilience, Agility and Innovation in Turbulent Times; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- D’aveni, R.A. Hypercompetition; Simon and Schuster; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garbelli, M. Performance Measurement and Global Networks; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mella, P.; Gazzola, P. As the turbulent environment in periods of accelerated dynamics modifies structures and functions of viable firms. Munic. Util. Ser. Econ. Sci. 2016, 127, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Selin, S.; Myers, N. Tourism marketing alliances: Member satisfaction and effectiveness attributes of a regional initiative. J. Travel Tour. Res. 1998, 7, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Formica, S.; O’Leary, J.T. Searching for the future: Challenges faced by destination marketing organizations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P. Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 607–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, L.S. Sami tourism in destination development: Conflict and collaboration. Polar Geogr. 2016, 39, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornhorst, T.; Ritchie, B.; Sheehan, L. Determinants of tourism successfor DMOs and destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders’perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H.; Boucher, X. The role of collaborative networks in sustainability. In Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- King, J. Destination marketing organizations—Connecting the experience rather than promoting the place. J. Vacat. Mark. 2002, 8, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Cooper, C. Marketing and destination growth: A symbiotic relationship or simple coincidence? J. Vacat. Mark. 2002, 9, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J.; Gray, B. Toward a comprehensive theory of collaboration. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1991, 27, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. (Eds.) Tourism Collaboration and Partnerships: Politics, Practice and Sustainability; Chanel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2000; pp. 200–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Tourism Collaboration and Partnership; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Co-operative tourism planning in a developing destination. J. Sustain. Tour. 1998, 6, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.; Scheyvens, R. Development Alternatives in the Pacific: How Tourism Corporates Can Work More Effectively with Local Communities. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R.; Fesenmaier, J.; Van Es, J.C. Factors for success in rural tourism development. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W.; Laing, J. Public–private partnerships for nature-based tourist attractions: The failure of Seal Rocks. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czernek, K.; Czakon, W. Trust-building processes in tourist coopetition: The case of a Polish region. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V.M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saito, H.; Ruhanen, L. Power in tourism stakeholder collaborations: Power types and power holders. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, S.A.; Ness, H.; Grønseth, B.O.; Aarstad, J. Development of tourism destinations: An integrated multilevel perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybers, T.; Bennett, J. Environmental management and the competitiveness of nature-based tourism destinations. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2003, 24, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybers, T.; Bennett, J. Inter-firm cooperation at nature-based tourism destinations. J. Socio-Econ. 2003, 32, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Stewart, W.P. Rural Tourism Development: Shifting Basis of Community Solidarity. J. Travel Res. 1996, 34, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.B.; Getz, D. Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiehm, J.H.; Townsend, N. The U.S. Army War College: Military Education in a Democracy; Temple University Press: Phyladelphia, PA, USA, 2002; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N.; Su, P. Selection of partners in virtual enterprise paradigm. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2005, 21, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, P.K.; Hardaker, G.; Carpenter, M. Integrated flexibility—Key to competition in a turbulent environment. Long Range Plan. 1996, 29, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, M.; Bolton, R. The industrial virtual enterprise. Commun. ACM 1997, 40, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil. Diverse Shades of Flexibility and Agility in Business. In Systemic Flexibility and Business Agility. Flexible Systems Management; Sushil, Chroust, G., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Janssen, M. From policy implementation to business process management: Principles for creating flexibility and agility. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, S61–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.G.; Lu, W.F. A framework of implementation of collaborative product service in virtual enterprise. In Proceedings of the SMA ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM—Innovation in Manufacturing Systems and Technology, Singapore, 17–18 January 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.; Kang, D.; Chae, H.; Kim, K. An enterprise architecture framework for collaboration of virtual enterprise chains. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 35, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, C. Strengthening regional cohesion: Collaborative networks and sustainable development in Swiss rural areas. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, B.; Sen, T.; Kilic, S.E. Formation of dynamic virtual enterprises and enterprise networks. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2007, 34, 1246–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, B.; Sen, T.; Kilic, S.E. Ahp model for the selection of partner companies in virtual enterprises. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 38, 367376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malone, M.; Davidow, W. Virtual corporation. Forbes 1992, 150, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Davidow, W.H. The Virtual Corporation: Structuring and Revitalizing the Corporation for the 21st Century. 1992. Available online: http://papers.cumincad.org (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Childe, S.J. The extended concept of co-operation. Prod. Plan. Control 1998, 9, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, J.; Zhang, J. Extended and virtual enterprises–similarities and differences. Int. J. Agil. Manag. Syst. 1999, 1, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, R.J.; Baldo, F.; Alves-Junior, O.; Dihlmann, C. Virtual Enterprises: Strengthening SME Competitiveness via Flexible Business Alliances. In Competitive Strategies for Small and Medium Enterprises; North, K., Varvakis, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H.; Ollus, M. ECOLEAD: A holistic approach to creation and management of dynamic virtual organizations. In Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H. (Eds.) Infrastructures for Virtual Enterprises: Networking Industrial Enterprises IFIP TC5 WG5. 3/PRODNET Working Conference on Infrastructures for Virtual Enterprises (PRO-VE’99), Porto, Portugal, 27–28 October 1999; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzounis, V.; Tshammer, V. A framework for virtual enterprise support services. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 5–8 January 1999; HICSS-32, Abstracts and CD-ROM of Full Papers. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A.; Schmidt, H.; Gilbert, D.R. Formal Models of Virtual Enterprise Architecture: Motivations and Approaches. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS), Taipei, Taiwan, 9–12 July 2010; p. 117. Available online: http://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2010/117 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Liu, P.; Raahemi, B.; Benyoucef, M. Knowledge sharing in dynamic virtual enterprises: A socio-technological perspective. Knowl. Based Syst. 2011, 24, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyall, A.; Garrod, B.; Wang, Y. Destination collaboration: A critical review of theoretical approaches to a multi-dimensional phenomenon. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Collaborative destination marketing: Understanding the dynamic process. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, E.; Vanneste, D. Tourism networks unravelled; a review of the literature on networks in tourism management studies. Tour. Manag. Persp. 2015, 15, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chim-Miki, A.F.; Batista-Canino, R.M. Tourism coopetition: An introduction to the subject and a research agenda. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 1208–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melian-Gonzalez, A.; García-Falcón, J.M. Competitive potential of tourism in destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 720–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C. Facebook’s New Multilingual Composer Lets You Post in Several Languages at Once. 2016. Available online: www.theverge.com (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Mun, J.; Shin, M.; Lee, K.; Jung, M. Manufacturing enterprise collaboration based on a goal-oriented fuzzy trust evaluation model in a virtual enterprise. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 56, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Advantage, C. Creating and sustaining superior performance. Compet. Advant. 1985, 167, 167–206. [Google Scholar]

| Author | Features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camarinha-Matos et al. [47] | - Business opportunity | - Temporary alliance | - Shared skills | - Shared resources | - Supported by several tools (e.g., computer networks, IT) |

| Davidow and Malone [42] | - A common aim | - Minimizing costs | - Maximizing efficiency | - Realizing an aggregate value chain | |

| Childe [43] | - Purchasing company | - Several suppliers | - Common aim | - Shared returns | |

| Browne and Zhang [44] | - Specific aim | - Specific markets | - Shared resources | - Shared costs | |

| Ouzounis and Tshammer [48] | - Different business domains collected | - Shared business processes | |||

| Goel et al. [49] | - Business opportunity | - Temporary alliance | - A common goal | - A common manifesto | - Partners completely free to join or drop out at any time |

| Rabelo et al. [45] | - Dynamic and temporary aggregation | - Logical aggregation | - Partners are autonomous | - Partners are heterogeneous | - Partners are geographically dispersed |

| Purpose | Organizational Structure | Costs and Resources Involved | Lifetime | Technology | Participation | Reconfigurability | Dynamicity | Partner Dependency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual enterprise | Exploit a specific business opportunity | Controlled by common goal and manifesto | Low cost, labour-related. | Mainly indirect | Ad hoc, temporary | Necessary to make it effective | Partners join or drop any time; may be involved in multiple VEs | Very high | Very high | Low |

| Extended enterprise | Seamlessly integrate external entities/partners | Controlled by a main enterprise, who extend its boundaries vertically in the value chain | Moderate to low cost, labour-related. Mainly indirect | Long-term and Stable | Not directly connected | Participants may join exclusively | Low | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Interfirm network | Increase competitiveness | Differs depending on cases | Direct and indirect (HR, knowledge, infrastructures, etc.) | Long-term and stable | Not directly connected | Participants may join the network exclusively | Low | Moderate | High, competencies | |

| YEAR | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Days Stayed | 3.83 | 3.73 | 3.73 | 3.72 | 3.72 |

| Arrivals | 2,308,488 | 2,480,647 | 2,687,679 | 2,809,688 | 2,799,559 |

| % Foreign | 54% | 55% | 57% | 57% | 57% |

| Languages | Tourist Stays | % |

|---|---|---|

| German | 3,826,685 | 38.2 |

| English | 1,019,731 | 10.18 |

| Dutch | 914,051 | 9.12 |

| French | 338,733 | 3.38 |

| Main Subareas | Partners Involved |

|---|---|

| Brescia city and Hinterland | Assessorato al Turismo del Comune di Brescia Fondazione Brescia Musei Strada del Vino Colli dei Longobardi |

| Garda Lake | Consorzio lago di Garda Lombardia Strada dei Vini e dei Sapori del Garda |

| Iseo Lake | Visit Lake Iseo |

| Franciacorta | Consorzio Franciacorta Strada del Franciacorta |

| Idro Lake and the Sabbia Valley | AGT Valle Sabbia e Lago d’Idro |

| Camonica Valley | DMO Valle Camonica Comprensorio Pontedilegno-Tonale |

| Trompia Valley | Comunità Montana di Valle Trompia |

| Lowlands of Brescia | Fondazione Pianura Bresciana Fondazione Castello di Padernello |

| Language | Post Content | Link |

|---|---|---|

| ITA | Prenotate uno spettacolo di opera, danza o musica al Teatro Grande, uno dei più bei teatri classici italiani. Godetevi un caffè tra gli affreschi veneziani dello sfavillante foyer. Brescia, che sorpresa! | Bit.ly/TeatroGrande |

| DE | Buchen Sie eine Opern-, Tanzoder Musikaufführung im Teatro Grande, einem der schönsten klassizistischen Theater Italiens. Genießen Sie einen Kaffee unter den venezianischen Fresken des glänzenden Foyers. Brescia, was für eine Überraschung! | Bit.ly/TeatroGrandeDN |

| EN | Book a ticket to the opera, a dance or a music show at Teatro Grande, one of the most beautiful classical Italian theatres. Enjoy a coffee amidst the wonderful Venetian frescos in the sparkling foyer. Brescia, never fail to surprise me! | Bit.ly/TeatroGrandeEN |

| FR | Réservez un spectacle d’opéra, de danse ou un concert au Teatro Grande, un des plus beaux théâtres anciens d’Italie. Dégustez un bon café dans le splendide foyer, décoré de fresques vénitiennes. Brescia, quelle surprise! | Bit.ly/TeatroGrandeFR |

| NL | Boek een heerlijk avondje opera, dans of muziek in het Teatro Grande, een van de mooiste klassieke theaters van Italië. Geniet van een heerlijke espresso onder de Venetiaanse fresco’s in de indrukwekkende foyer. Brescia, wat een verrassing! | Bit.ly/TeatroGrandeNL |

| Time | Followers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | ++ | - - | # Variation | % Variation | |

| Spring * | 92,192 | 1117 | 840 | 277 | 25% |

| Summer | 92,217 | 645 | 674 | −29 | −4% |

| Autumn | 92,442 | 521 | 438 | 83 | 16% |

| Winter ** | 92,780 | 654 | 174 | 480 | 73% |

| User Language | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 (January–February) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dutch | +539.40% | +629.90% | +301.62% |

| French | +245.45% | +257.33% | +63.41% |

| English | +188.03% | +231.25% | +85.58% |

| German | +151.39% | +288.96% | +113.75% |

| Substages | |

|---|---|

| Creation | Common aim identification (purpose) Partner selection Resource attribution |

| Operation | Collaborative VE planning (timing, milestones, etc.) Operation of the virtual enterprise |

| Evolution | Mid-process check Mid-process adaptation of collaborative VE planning |

| Termination and Dissolution | Achievement of the common aim Dissolution of the VE or further evolution in a new VE/in cooperation |

| Virtual Enterprise Life Cycle Stages | Bresciatourism VE: Localization Strategy to Promote the Destination through Social Media | |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | 1. Common aim identification (purpose) | 1. Development of a localization social media strategy for the comprehensive and effective promotion of the overall destination. |

| 2. Partner selection | 2. Partner selection adopts two criteria: inclusion of every area; relevance in terms of tourism attraction ability. | |

| 3. Resource attribution | 3. Partner decided to devote a chosen slack each, to make the project effective. | |

| Operation | 4. Collaborative VE planning | 4. Detailed VE planning was released |

| 5. Operation of the virtual enterprise | 5. The VE operation activities started 1 March 2018, with the first post released. | |

| (Evolution) | 6. Mid-process check | 6. A mid-process check was planned at the halfway point of the project. |

| 7. Mid-process adaptation of the collaborative VE planning | 7. For the specific project, no mid-process adaptation was required. | |

| Dissolution | 8. Achievement of the common aim | 8. The project was intended to close on 31 December 2018, with the last localized post released. |

| 9. Dissolution of the VE or further evolution in a new VE | 9. In a follow-up period, partners agree to dismantle the VEt for the achievement of the aim. | |

| Purpose | Achieve a particular aim (business opportunity) in sustaining the whole destination’s heritage promotion. |

| Coordination and Trust | The DMO plays a pivotal role in generating both the system of partners and the common rules, coordinating resources, activities and efforts and measuring results. Heading the system, the DMO should generate trust among participants. |

| Partner selection | Should be representative of the whole destination for comprehensive development. |

| Participation | Participants are entities dynamically involved in more than one VE at the same time but with no overlapping aims (nonexclusive basis). |

| Partner Dependency | Low, but mainly because coordination intends to avoid overlapping for the activities run by the VE. |

| Organizational structure | Controlled by a common goal and manifesto, requires a formal business plan. Activities should be planned, and timing should be defined. The DMO can serve as facilitators and coordinators of partners’ actions. |

| Lifetime | Ad hoc and temporary, depends on the VE’s purpose (or intention). |

| Costs and Resources involved | Low cost, mainly indirect and labour-related. |

| Technology | Conditio sine qua non to make it effective:

|

| Reconfigurability | Very high, mid-process adjustments. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garbelli, M.; Gabriele, M. Reshaping the Role of Destination Management Organizations: Heritage Promotion through Virtual Enterprises—Case Study: Bresciatourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084471

Garbelli M, Gabriele M. Reshaping the Role of Destination Management Organizations: Heritage Promotion through Virtual Enterprises—Case Study: Bresciatourism. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084471

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarbelli, Maria, and Manuel Gabriele. 2021. "Reshaping the Role of Destination Management Organizations: Heritage Promotion through Virtual Enterprises—Case Study: Bresciatourism" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084471

APA StyleGarbelli, M., & Gabriele, M. (2021). Reshaping the Role of Destination Management Organizations: Heritage Promotion through Virtual Enterprises—Case Study: Bresciatourism. Sustainability, 13(8), 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084471