Transition and Transformation of a Rural Landscape: Abandonment and Rewilding

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

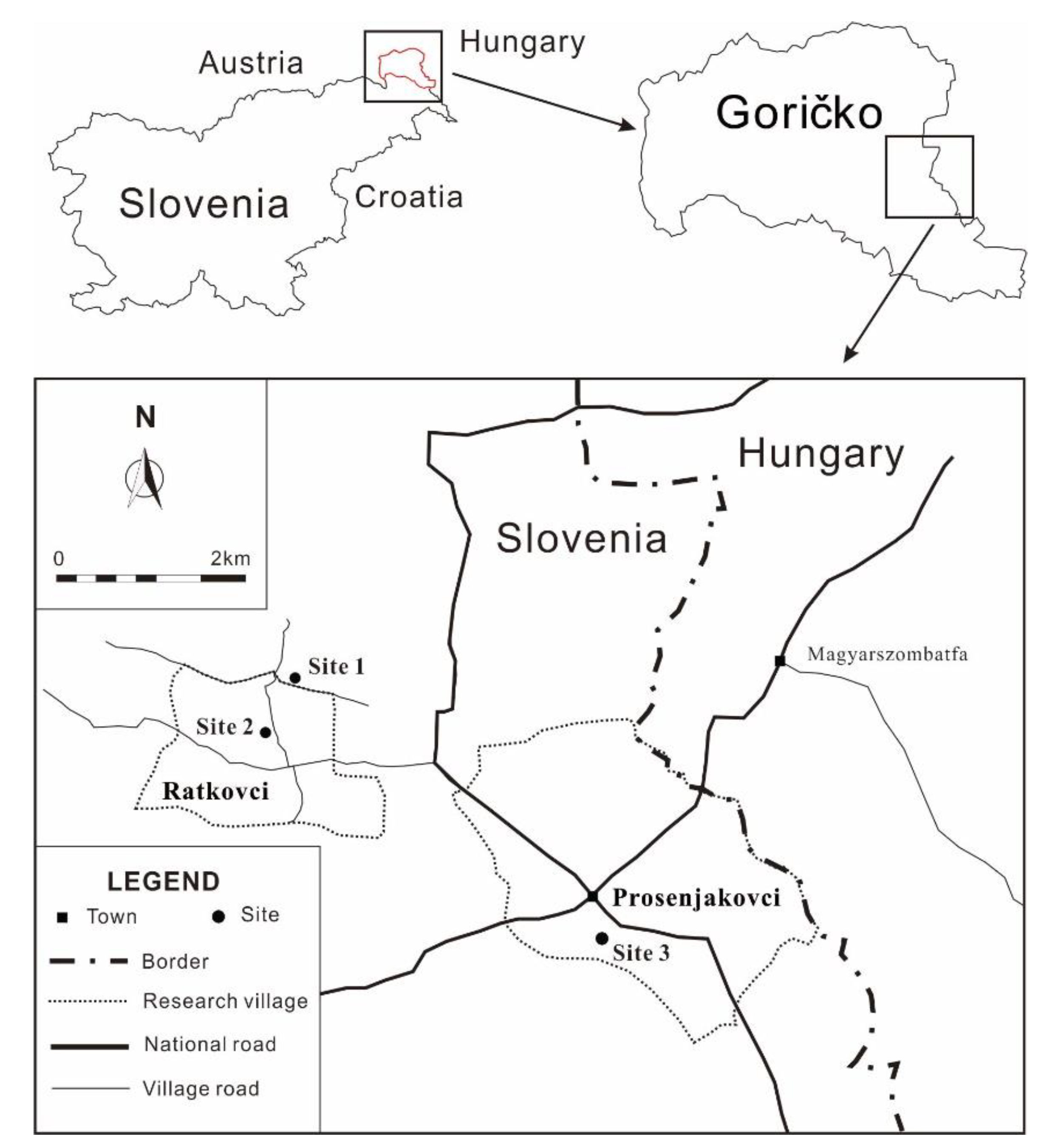

2.1. Study Area and Study Sites

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evidence of Former Human Presence

3.1.1. Items Considered Household Artefacts in Site 1

3.1.2. Items Considered Household Artefacts in Site 2

3.2. Ecological Evidence of Former Land Use

3.3. Transformation from Anthropogenic Use to Ecological Habitats

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Register Number | Artefact Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| II:1 | Trug | A movable wooden feed trough on runners in poor condition due to woodworm |

| II:4 | Donkey carts (2) | One larger with willow woven tray, axles of both worm eaten However, the wheels (of beech or black locust) were in good condition |

| II:5 | Wooden ladder | Extensive patina indicating long use, positioned to provide access to the hay loft |

| VI:1 | Hay rake | Extensive patina, wear and mends indicated long use |

| VIII:1 | Stool | Wooden stool with patina in fair condition |

| VIII:2 | Amphora (2) | Pottery amphora simple external decoration, broken flange rims, internal glaze one minus handle and has string substitute |

| VIII:3 | Copper bowl | Part of an alcohol distillation plant |

| VIII:4 | Wine keg | Oak keg in good condition |

| IX:1 | Wooden bench | Finely crafted pine bench with doweling joints, minor nail mends |

| IX:2 | Oak chairs (2) | Hand crafted chairs in good condition |

| Register Number | Artefact Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I:A i | Prayer book | An Evangelical volume with owners’ signatures inside the front cover, dated 1906, eaten by mice |

| I:A ii | Religious calendar | An Evangelical calendar dated 1965 |

| I:A iii | Religious calendar | An Evangelical calendar dated 1972 |

| I:A iv | Coins | Three Hungarian coins and one Slovene coin |

| I:B i | Religious calendar | An Evangelical calendar dated 1974 |

| I:B ii | Tax receipt | For the year 1924 addressed to Ivanševci 35 |

| I:B iii | Photograph | Document size, male portrait |

| I:B iv | Doctor’s notice (three) | Dated 1969 for a broken wrist. Three documents in total |

| I:B v | Income tax booklet | Dated 1951 |

| I:B vi | Newspaper fragment | Dated 1983 very poor condition |

| I:B vii | Cash benefit | Dated 1969, kombinat Pomurka |

| I:B viii | Extract from Marriage Register | Dated 1913, Ivan Grabar married Franciška Hujs |

| I:B ix | Envelope | Notation, not dated |

| I:B x | Doctor’s notice | Dated 1969 for a broken wrist |

| I:B xi | Co-operative pass | Dated 1946 |

| I:B xii | Goods receipt | Dated 1969, kombinat Pomurka |

| I:B xiii | Tax receipt | Dated 1969 |

| I:B xiv | Prescription medicine | Lanitop packet containing tablets |

| I:B xv | Tax receipt | Dated 1922, addressed to Ivanševci 35 |

| I:B xvi | Land survey | Undated, written by hand a summary of agricultural land |

| I:B xvii | Tax receipt | Dated 1923, addressed to Lončarovci 48 |

| I:B xviii | Tax receipt | Dated 1922, addressed to Lončarovci 48 |

| I:B xix | Tax receipt | Dated 1924, addressed to Ivanševci 35 |

| I:B xx | Tax receipt | Dated 1925, addressed to Lončarovci 48 |

| I:B xxi | Tax receipt | Dated 1924, addressed to Lončarovci 48 |

| I:B xxii | Tax receipt | Dated 1922, addressed to Lončarvci 48 |

| I:B xxiii | Official envelope | Dispatched from Murska Sobota, stamped, addressed to Josip Hujs |

| I:B xxiv | Document | Dated 1977, a decision on tax payments, eaten by mice |

| I:B xxv | Tax receipt | Dated 1921, for both addresses: Lončarovci 48 & Ivanševci 35 |

| I:B xxvi | Goods receipt | Undated, for cellulose (plastic?), kombinat Pomurka |

| I:B xxvii | Tax receipt | Dated 1968 |

| I:B xxviii | Contract | Dated 1965, kombinat Pomurka, an agri-industrial combine (purchase?) |

| I:B xxix | Tax receipt | Dated 1923, addressed to Lončarovci 48 |

| I:B xxx | Tax receipt | Dated 1925, addressed to Ivanševci 35 |

| I:B xxxi | Tax receipt | Undated, addressed to Lončarovci 54 |

| I:B xxxii | Tax receipt | Dated 1922, addressed to Ivanševci 35 |

| I:B xxxiii | Tax receipt | Dated 1923, addressed to Lončarovci 48 |

| I:B xxxiv | Land survey | Undated summary of agricultural land |

| I:B xxxv | Death certificate | Dated 1961, for Ivan Grabar |

| I:B xxxvi | Instructions | Undated, in the case of natural disaster |

| I:B xxxvii | Cash benefit | Undated, kombinat Pomurka |

| I:B xxxviii | Account book | Undated, agricultural co-operative |

| I:B xxxix | Certificate | Undated, Agricultural producers’ insurance |

| IB xl | seeds | Approximately 1000 been seeds, unviable |

References

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=0900001680080621 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Oliver, A. Preface. In Europe’s Cultural Landscape: Archaeologists and the Management of Change; Fairclough, G., Rippon, S., Eds.; Europae Archaeologiae Consilium: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, A.T.; Rackham, O. The Nature of Mediterranean Europe: An Ecological History; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Agnoletti, M. Rural landscape, nature conservation and culture: Some notes on research trends and management approaches from a (southern) European perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 126, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.; Šmid Hribar, M. Assessment of land-use changes and their impacts on ecosystem services in two Slovenian rural landscapes. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2019, 59, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agnoletti, M. (Ed.) Cultural Values for the Environment and Rural Development. In Italian Historical Rural Landscape; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loures, L.; Horta, D.; Santos, A.; Panagopoulos, T. Strategies to reclaim derelict industrial areas. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2006, 2, 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, C. An evaluation of human intervention in abandonment and postabandonment formation processes in a deserted Cretan village. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2013, 26, 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Aesthetic appreciation of landscape. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Howard, P., Thompson, I., Waterton, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Given, M. Commotion, collaboration, conviviality: Mediterranean survey and the interpretation of landscape. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2013, 26, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, C. Observed Decay: Telling Stories with Mutable Things. J. Mater. Cult. 2006, 11, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, C.; Beilin, R.; Folke, C.; Lindborg, R. Farmland abandonment: Threat or opportunity for biodiversity conservation? A global review. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O. (Un)ethical geographies of human-non-human relations, encounters, collectives and spaces. In Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Amimal Reltions; Philo, C., Wilbert, C., Eds.; Routledge: Bristol, UK, 2000; pp. 268–291. [Google Scholar]

- Torkar, G.; Čarni, A.; Dešnik, S.; Burnet, J.; Ribeiro, D. Kulturna krajina in ohranjanje narave Prekmurja. In Kulturna Krajina ob Reki Muri; Žajdela, B., Ed.; Regionalna Razvojna agencija Mura: Murska Sobota, Slovenia, 2012; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Darby, H.C. The Domesday Geography of Midland England; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Wrbka, T.; Erb, K.; Schulz, N.B.; Peterseil, J.; Hahn, C.; Haberl, H. Linking pattern and process in cultural landscapes. An empirical study based on spatially explicit indicators. Land Use Policy 2004, 21, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanc, M.; Printsmann, A.; Palang, H.; Skowronek, E.; Woloszyn, W.; Gyuró, E.K. Comprehension of rapidly transforming landscapes of Central and Eastern Europe in the 20th century. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2004, 44, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urbanc, M.; Fridl, J.; Kladnik, D.; Perko, D. Atlant and Slovene National Consciousness in the Second Half of the 19th Century. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2006, 46, 251–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skokanóva, H. Methodology for Calculation of Land Use Change Trajectories and Land Use Change Intensity; Silva Taroucy Research Institute for Landscape and Ornamental Gardening: Brno, Czech Republic, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lettner, C.; Wrbka, T. Historical Development of the Cultural Landscape at the Northern Border of the Eastern Alps: General Trends and Regional Peculiarities. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Landscape History, Workshop on Landscape History, Sopron, Hungary, 22 April 2010; Balázs, P., Konkoly-Gyuró, E., Eds.; University of West Hungary Press: Sopron, Hungary, 2010; pp. 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Rodela, R.; Torkar, G. Identities and Strategies: Raising Awareness. Survey of Oral History, WP6.1 Repor; Univerza v Novi Gorici: Nova Gorica, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaligarič, M.; Sedonja, J.; Šajna, N. Traditional agricultural landscape in Goričko Landscape Park (Slovenia): Distribution and variety of riparian stream corridors and patches. Landsc Urban Plan 2008, 85, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvanec, B. Arhitektura Slovenije. 2, Vernakularna Arhitektura, Severovzhod; Fakulteta za Arhitekturo: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, J. Za Prekmurskimi Kolniki; Tiskovna Zadruga: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Trstenjak, A. Slovenci na Ogrskem: Narodopisna in Književna Črtica: Objava Arhivskih Virov; Pokrajinski Arhiv Maribor: Maribor, Slovenia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Statistični Urad Republike Slovenije. Available online: http://www.stat.si/ (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Orožen Adamič, M.; Perko, D.; Kladnik, D. (Eds.) Krajevni Leksikon Slovenije; DZS: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Prosenjakovci. Available online: http://prosenjakovci.naspletu.com/ (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Stopar, I. Grajske stavbe v Prekmurju. In Katalog Stalne Razstave; Balažic, J., Kerman, B., Eds.; Pokrajinski Muzej: Murska Sobota, Slovenia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kladnik, K. Settling and settlements. In Slovenia: A Geographical Overview; Orožen Adamič, M., Ed.; Association of the Geographical Societies of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2004; pp. 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Maučec, M. Podstenj in priklet v prekmurski hiši. Časopis Zgodovino Narodop. XXXIV 1939, 3–4, 176–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zrim, K. Moji Spomini na Družino Matzenauer; Občina Moravske Toplice: Prosenjakovci, Slovenia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, D.; Ellis Burnet, J. Kulturni predmeti v estetski pokrajini. In Prekmurje-Podoba Panonske Pokrajine; Godina, M.G., Ed.; Založba ZRC: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Smej, Š. O Slovencih na Ogrskem. Vestnik 1986, 37, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Smodiš, R.Š. Arhitekturna dediščina. In Vzhodno v Raju: Drobtinice iz Pomurja; Rous, S., Fujs, M., Dešnik, S., Smodiš, R.Š., Pšajd, J., Buzeti, T., Karas, R., Eds.; Evrotrade: Murska Sobota, Slovenia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vugrinec, J. Videnje sodobne prekmurske hiše skozi prizmo stoletnih sten. Zb. Soboškega Muz. 2008, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rondinini, C.; Boitani, L. Habitat Use by Beech Martens in a Fragmented Landscape. Ecography 2002, 25, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhatič Širnik, R. Lov in Lovci Skozi Čas; Lovska Zveza Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reimoser, F.; Reimoser, S. Long-term trends of hunting bags and wildlife populations in Central Europe. Beiträge Zur Jagd- Und Wildforschung 2016, 41, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, O.; Walz, U.; Decker, A. Historical Landscape Elements: Part of our Cultural Heritage—A Methodological Study from Saxony. In The Carpathians: Integrating Nature and Society Towards Sustainability; Kozak, J., Ostapowicz, K., Bytnerowicz, A., Wyzga, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ellis Burnet, J.; Ribeiro, D.; Liu, W. Transition and Transformation of a Rural Landscape: Abandonment and Rewilding. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095130

Ellis Burnet J, Ribeiro D, Liu W. Transition and Transformation of a Rural Landscape: Abandonment and Rewilding. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095130

Chicago/Turabian StyleEllis Burnet, Julia, Daniela Ribeiro, and Wei Liu. 2021. "Transition and Transformation of a Rural Landscape: Abandonment and Rewilding" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5130. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095130