Abstract

This paper addresses open data, open governance, and disruptive/emerging technologies from the perspectives of disaster risk reduction (DRR). With an in-depth literature review of open governance, the paper identifies five principles for open data adopted in the disaster risk reduction field: (1) open by default, (2) accessible, licensed and documented, (3) co-created, (4) locally owned, and (5) communicated in ways that meet the needs of diverse users. The paper also analyzes the evolution of emerging technologies and their application in Japan. The four-phased evolution in the disaster risk reduction is mentioned as DRR 1.0 (Isewan typhoon, 1959), DRR 2.0 (the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake, 1995), DRR 3.0 (the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami: GEJE, 2011) and DRR 4.0 (post GEJE). After the GEJE of 2011, different initiatives have emerged in open data, as well as collaboration/partnership with tech firms for emerging technologies in DRR. This paper analyzes the lessons from the July 2021 landslide in Atami, and draws some lessons based on the above-mentioned five principles. Some of the key lessons for open data movement include characterizing open and usable data, local governance systems, co-creating to co-delivering solutions, data democratization, and interpreting de-segregated data with community engagement. These lessons are useful for outside Japan in terms of data licensing, adaptive governance, stakeholder usage, and community engagement. However, as governance systems are rooted in local decision-making and cultural contexts, some of these lessons need to be customized based on the local conditions. Open governance is still an evolving culture in many countries, and open data is considered as an important tool for that. While there is a trend to develop open data for geo-spatial information, it emerged from the discussion in the paper that it is important to have customized open data for people, wellbeing, health care, and for keeping the balance of data privacy. The evolution of emerging technologies and their usage is proceeding at a higher speed than ever, while the governance system employed to support and use emerging technologies needs time to change and adapt. Therefore, it is very important to properly synchronize and customize open data, open governance and emerging/disruptive technologies for their effective use in disaster risk reduction.

1. Introduction

Governance is the way rules, norms, and actions are structured and sustained. The words “governance” and “government” are often mixed up, and it is often considered that the government is the custodian of governance. A variety of bodies related to decision-making can govern and can be responsible for taking responsibility for specific actions. From the national to the local level, the level of governance varies both in terms of resources, the implications of decisions taken, and the roles of stakeholders. Governance is considered the art of decision-making. If one looks back to the origin of governance, it was initially people-based, whereby the people and community took the collective decisions and were responsible for the decision being taken. Then, gradually, after the formation of the state, the power and responsibility of governance fell into the hands of governments. In recent years, the context and process of governance has been changing, and different terms of global governance, public governance, corporate governance and community governance are emerging. Additionally, in thematic sectors, the increasing importance of environmental governance, health governance, and educational governance are being seen. With the advancement of technology, internet governance, blockchain governance, and information technology governance are also emerging. Thus, the governance landscape is gradually expanding, and in each sector or level (from global to local), the role of governance is becoming more important.

Governance in the disaster risk reduction field has been discussed and highlighted in different publications. Ref. [1] on disaster governance identified social, political and economic dimensions, and emphasized that it is an evolving concept, which changes dynamically over time. The paper also highlighted the importance of state and civil society relationships. Ref. [2] analyzed the importance of public administrations in general, and more specifically in disaster and emergency management. The balance of democracy and bureaucracy is considered very important in timely decision-making. In a similar analysis by [3], the importance of collaborative decision-making is highlighted, whereby nontraditional approaches are emphasized with non-hierarchical structures and flexibility. The collaboration of state and non-state actors during emergencies is also highlighted by [4] in the case of Bangladesh. The study highlighted the importance of accountability, participation, collaboration and leadership during the response, evacuation, rescue and relief in a post-disaster situation. Ref. [5] argues for the integration of disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation (CCA) with governance goals, and presents a framework that is sensitive to context-specific variables, norms and networks. In a recent analysis [6], the authors discussed the complexities of governance and its implications to Sendai priority 2. The paper emphasized the importance of local governance in DRR, and suggested four strategies for addressing vulnerabilities as root causes, which were the inclusive approach, the governing of urban disasters, the governing of CCA, and risk reduction for resilience. In summary, governance in DRR is attracting attention in the literature, emphasizing decision-making before, during and after a disaster. The incorporation of the risk reduction concept is considered as the key to governance in both DRR and CCA.

Within this diverse and dynamic governance landscape, in recent years, the importance of “Open Governance” has been highlighted in different sectors. Open governance is defined as the “culture of governance based on innovative and sustainable public policies and practices inspired by the principles of transparency, accountability and participation that fosters democracy and inclusive growth” [7]. Open governance is very much linked to public policies. Robert Putnam, in his comments on social capital and civic engagement, has stressed that both these elements can contribute by creating “strong, responsive and effective representative institutions” [8]. Social capital, as defined in terms of networks, norms, trust and leadership, can enable communities to participate and engage in decision-making along with the governments proactively. Although the emergence of the term open governance as well as government has been observed in the last 30–40 years, the concept of transparent information in the context of decision-making dates back to the 17th century, when Thomas Jeffreson stated that “in order for people to trust their own government, they need to be well informed”. Therefore, people’s trust in governance becomes a core issue of any open governance system. Ref. [9] narrowed down the concept of open government to “a multilateral, political and social process, which includes in particular transparent, collaborative, and participatory action by government and administration”.

Open governance is often considered as a function of transparency, participation and accountability in terms of decision-making. Different international efforts are being made to enhance transparency, such as the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI: focusing on international aid and civil society engagement), the Transparency and Accountability Initiative (focusing both on public and private sectors), Transparency International [10], Publish the Way You Pay (includes citizens in the decision-making process), the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI: global standards for transparency in government revenues from extractive industries), Open Government Partnership (OGP: international platform for reforms) and so on [11]. Ref. [7] defined ten guiding principles for open and inclusive policy-making, as: (1) commitment, (2) rights, (3) clarity, (4) time, (5) inclusion, (6) resources, (7) coordination, (8) accountability, (9) evaluation and (10) active citizenship.

With the evolution of digital technologies and accessibility and the availability of digital tools, open governance is taking a new global shape, both in the developed as well as in developing countries. Ref. [12] suggested three specific domains of open governance: (1) crisis management, (2) environmental governance and (3) security control. As an example of the first category, after the Christchurch earthquake of 2010 and 2011, university students, in cooperation with the local government and civil society, created an online regional map using open government data, which was used as a platform for information sharing immediately after the disaster. It was stated that the ad-hoc nature of the collaboration helped different stakeholders to come together at the right time and share their expertise and experiences. Similarly, citizen science has played a role in the recent pandemic responses as well [13], especially in the case of Iran. In the second category of environmental governance, the role of citizen science and volunteers is prominent in addressing and solving several cases [12]. In a classic example from Kathmandu, Nepal, a group of young volunteers and environmental activists used citizen science and open-source data mapping to save trees in and around the city to protect them from the environmental consequences of road infrastructure projects. In the third regime of security control, there are numerous examples derived from the Arab Spring, during which videos were uploaded through citizen journalism, or from New York, where the crime map is open to the public.

From the perspective of disaster risk management, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Management, issued in 2015, states that “disaster risk management policies and practices should promote real-time access to reliable data, the use of space-based and ground-based information, including geographic information systems (GIS), and the use of innovative information and communication technologies to enhance the collection, analysis and delivery of measurement tools and data”. In Japan, the open data concept gained momentum after the East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011, and disaster prevention information is considered to be the most suitable data for disclosure. In 2015, more than 100 apps were listed on the Apple Store. In the beginning, most of the open data were public-centered [14]. Against this background, this paper analyzes the chronological evolution of Japan’s disaster risk reduction regime, with a specific focus on open data and the analysis of a case in Shizuoka prefecture. The paper attempts to draw some lessons, which can be useful beyond Japan.

2. Methods and Approaches

This paper explores the role of open governance and open data in the field of disaster risk reduction, with specific examples from Japan. First, an overview is given to explore the role of open data and open governance in the field of disaster risk reduction through a narrative review of changes in the initiative of disaster management and the lessons learned, and we extract the key concepts from them in terms of effectiveness, potential and future challenges. This is followed by a deeper analysis of Japan’s DRR, which sets forward some of the key principles of global open data and open governance. The evolution of Japan’s DRR field is scrutinized, and perspectives and challenges related to the new concept of Society 5.0 are reviewed.

The specific case of the Atami landslide disaster is analyzed from Japan to draw some conclusion regarding the effectiveness, potential uses and challenges of open data and open governance [15]. The case presented here is one of the first of a few recent examples wherein collaboration among stakeholders (both public and private) using open data in decision-making is demonstrated. The timing was critical, with Society 5.0 and Digital Agency at their initial stages of formulation and action, and open data/open governance is employed in both approaches. Data collection was conducted through a chronological review of newspapers and websites, as well as field observations, to understand disaster situations. The data were also collected in the context of participation in related seminars and semi-structured interviews with stakeholders, related to the responses to the disaster event, so as to explore the usage of open data and the role of open governance, referred to as the ethnographic approach [16,17]. Stakeholders include local government representatives, private sectors and open data experts. The contents of the discussion were: (1) the chronology of Shizuoka landslide event, (2) challenges and opportunities of open data, including its licensing issues, (3) the informal network among professionals and the government’s formal network, and (4) the possibility of upscaling the Shizuoka experience.

Japan has been at the forefront of disasters, in terms of their occurrences, as well as their mitigation, and the dissemination of DRR lessons through organizing three world conferences and contributing significantly to global DRR activities. In the discussion part, some specific conclusions and recommendations are drawn out, which have wider applications in open governance in different parts of the world. Although the governance itself is a context- and locality-specific issue, the basic principles drawn from the open data and open governance analysis can be applied to a wider socio-economic context.

3. Open Governance in Disaster and Development Field

Meijer et al. [12] have highlighted the importance of three critical issues for open governance: (1) openness of data, (2) data quality assurance and (3) open participation. Correspondingly, five core elements of open governance are also recognized: (1) radical openness, (2) citizen centricity, (3) corrected intelligence, (4) digital altruism and (5) crowdsourced deliberation. Markedly, citizen engagement has become core to open governance, for which open data becomes a critical determining factor. It has been gradually realized that citizens are not just the data receivers, rather they also serve as potential data providers, such as in terms of citizen science, citizen reporter, citizen volunteer and citizen experts. Co-creation, co-production and co-delivery therefore become critical for the open governance process. Ref. [18] argues that open governance also helps in the adaptive learning process, which is key to problem-solving with a higher level of satisfaction rate. Likewise, data transparency is also recognized to be a critical factor for this purpose.

Ref. [19] has analyzed the importance of open government data for disaster risk reduction. Herein, in relation to the definition put forward by Ref. [20], it is important to highlight that data is open when it is “accessed, reused and redistributed by anyone for any purpose including commercial reuse, free of charge and without any restrictions”. Open government data for development includes environmental protection, social inclusion and inclusive growth. To enhance open government data, there needs to be an open data policy, which can remove two important barriers: control and revenue.

In 2007, the Sebastopol Principles of Open Government Data [21] were prepared when thirty open government advicates gathered in California. Therein, eight core principles were defined to make stimulate open governance, namely: (1) complete, (2) primary, (3) timely, (4) accessible, (5) machine-processable, (6) non-discriminatory, (7) non-proprietary and (8) license-free. In addition to that, a few other principles were also recognized, such as: (1) online and free, (2) permanent, (3) trusted, (4) a presumption of openness, (5) documented, (6) safe to open and (7) designed with public input.

In 2011, the Global Facility for Disaster Risk Reduction (GFDRR) launched ‘Open Data and Resilience Initiative’ (Open DRI) to apply the concept of global open data movement into addressing disaster risk reduction. Ref. [22] engages with the governments to mainstream the importance of open data and utilizes simple, collaborative, crowdsourced mapping tools like Open Street Map. In that regard, five key principles of open data are adopted in the disaster risk reduction field: (1) open by default, (2) accessible, licensed and documented, (3) co-created, (4) locally owned and (5) communicated in ways that meet the needs of diverse users. Remarkably, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) has also called for openness in data and information sharing, while calling for stronger public and citizen engagement. The notion of openness can be customized based on mitigation and prevention, preparedness, response and recovery [22]. Although the use of open governance is still largely restricted in the DRR field, there are some recent examples such as GeoNode, which is an open-source visualization of geospatial data, and was used in 2013 after the typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Similary, Indonesia has also been utilizing InSAFE for impact assessment in the field in the field of DRR. In Nepal, ‘Open Cities’ uses details of the critical infrastructures like schools, hospitals, and other related government officials [22]. The platform of Open DRI also presents Open Cities in Africa (creating open spatial data on built and natural environment), Pacific islands (Cook Island, Fiji and several other island countries), East Europe and Cental America (Haiti, Guyana).

In summary, there are ever-increasing trends of utilizing open data and open governance in the field of DRR. These trends also foster a culture of innovation in governance and citizen and other stakeholder engagement in the area of DRR.

4. Japan’s Evolving Context of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR)

While Japan is prone to various types of disasters, the country has long been promoting efforts for disaster prevention based on the lessons learned from repeated major disasters. Apart from the 1923 Kanto earthquake, a few major landmark disasters which have influenced and changed the DRR notion and approach in Japan are: the Ise Bay Typhoon (1959), the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (1995), and the Great East Japan Earthquake (2011). Besides, the intensification of disasters brought about by the changing climate holds the potential to be equivalent to these significant disasters in the future. Moreover, the evolution of Japan’s DRR can be described into four phases as follows [23].

DRR 1.0: 1959 Ise Bay typhoon was the turning point of Japan’s early warning system. During the disaster, the government’s system for dealing with large-scale disasters was not yet in place, for instance the disaster-related laws were not unified, and the roles and responsibilities of each agency were not clear. To improve this situation, Japan has been developing a governance system that can function efficiently and effectively in times of emergency. In lines with that, the Disaster Countermeasure Basic Act was formulated as an umbrella strategy to address disaster-related issues, clarifying the roles and responsibilities of governments and stakeholders. At the national level, a unified system for disaster management was formed, which collaborates with the prefecture and local governments in times of emergency and disaster preparednesss. At the central level, the Central Disaster Management Council was formed, which supervises the formation/revision of legislations and develops future policies and strategies.

DRR 2.0: The turning point for this phase was the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, which was a massive earthquake with its epicenter directly underneath the city, causing enormous damage. A significant number of houses collapsed, and there was also a disruption of water, electricity, and gas (lifelines), paralysis of transportation, and a huge number of victims. In addition, the inadequacy of the crisis management system in the Prime Minister’s Office, as well as the initial information understanding and communication system, were major issues. Correspondingly, the following measures were taken to address the identified issues: (1) Enactment of the Law for the Promotion of Seismic Retrofitting of Buildings, and (2) Enactment of the Law for Supporting the Reconstruction of Disaster Victims’ Lives. Since the 1990s, “vulnerable people” were identified as the physically and mentally disabled, the injured and sick, the elderly with physical weakness and infants with poor understanding and judgment even if they are healthy on a daily basis. Foreigners with poor understanding of the Japanese system, tourists who are not familiar with the geography of the area are also considered “vulnerable”. While most of the information from the government was earlier written in Japanese language, adequate consideration was subsequently given for vulnerable people in disasters and emergency measures. In public relations activities as preventive measures, it has also been argued that detailed general information should be provided to the elderly, the disabled, and foreigners. The 2006 White Paper on Disaster Management [24] asks for evacuation support for those who need assistance, and the following three major problems have been identified: (1) the system for communicating information is not sufficiently developed, as there is insufficient coordination between disaster prevention-related departments and welfare-related departments; (2) the sharing and utilization of information has not progressed, and the number of those who can share the information is limited to protect their privacy, which makes it challenging to utilize the information at the time of a disaster; and (3) evacuation action support plans and systems have not been materialized, as there are no designated evacuation supporters for those who need assistance. After the disaster, a total of about 1.4 million volunteers rushed to the disaster area from all over Japan in what was called the “First Year of Volunteers”, which led to the establishment of specific items for “self-help” and “mutual-help” initiatives in the Basic Act on Disaster Countermeasures, such as the creation of an environment for disaster prevention activities by voluntary disaster prevention organizations and volunteers.

DRR 3.0: The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011 was the turning point for this phase. It was the largest earthquake in Japan’s recorded history, which triggered a massive tsunami that caused enormous and widespread damage, especially in the coastal areas of the Tohoku region. Herein, it has been pointed out that there was inadequate preparedness for a disaster of the maximum scale, and that there was an insufficient assumption of a combined natural and nuclear accident disaster. Additionally, the problem of inadequate information surfaced, such as in terms of update on daily lives and living situation during the long evacuation period after the disaster [25]. As the disaster struck the entire town, including public offices, the people were forced to evacuate to unfamiliar places, which lead to physical and mental stresses. Especially, the use of SNS (such as Twitter and Facebook) on devices such as smartphones and social media served as various vital relief functions such as damage information provision, safety identification, fund-raising, and moral support systems. It was noted that younger people were relatively more connected through social media. However, they are also victims of false information sharing more than the older people [26]. In the aftermath of the 2011 disaster, there were: (1) Review of damage assumptions and measures for large-scale earthquakes, (2) Positioning the concept of “disaster mitigation” as a fundamental principle for disaster prevention, (3) Disaster mitigation measures for the largest possible earthquake, tsunami, flood, and (4) Review of nuclear policy, including the establishment of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Particularly, the Basic Act on Disaster Control Measures has been amended to include a system that allows prefectures and the national government to supply goods at their own discretion without waiting for requests (push-type material support) [27]. The amendment also includes the establishment of a mechanism for the national government to support disaster response activities and take over emergency measures when a disaster severely impairs the functions of local governments. In addition, the Act on Recovery from Large-Scale Disasters was enacted to establish a framework for recovery in the event of a large-scale disaster.

DRR 4.0: Since “DRR 3.0”, the government has been strengthening disaster prevention measures against earthquakes, tsunamis, windstorms, floods, volcanic disasters, and other disasters by enacting and revising relevant systems based on the latest knowledge. As mentioned above, based on the occurrence of major disasters in the past, the system has been reviewed and systems have been improved each time. However, in response to the intensification of disasters caused by the ongoing climate change, it is important to recognize that the assumptions for disasters have changed significantly. In particular, it has been recognized as a fact that can likely delay the completion of countermeasures through the construction of facilities throughout the country as planned. While it is a prerequisite that governments (especially the national government) make the best use of their knowledge and experience as mentioned above, there is a limit on the amount of “public assistance” that can be provided in the event of a disaster. In regards to that, efforts are being made to realize a society in which each of the various actors, such as the local community, the business community, residents and businesses, can rebuild their mutual connections and networks, thereby enhancing the resilience of society as a whole and preparing for disasters autonomously. The use of quasi-zenith satellites and drones is also being promoted according to the type of disaster and the scale of the affected area. In the event of a disaster, accurate information collection and prompt communication are gaining utmost importance. In addition, it is important to make systems for aggregating and viewing local information using social media, which is available from normal times in order to ensure user operability and convenience. Therefore, in order for citizens and businesses to proactively deal with disaster risks, it is essential to share the critical information sufficiently and encourage continuous efforts in each region to foster an awareness of relevant preparedness measures. This notion brings up the context of open governance in DRR in Japan, as perceived in DRR 4.0. From a complete prevention policy, a shared responsibility is arising gradually, and it is important to look at that reality.

One of the key aspects of DRR 4.0 is the establishment of SIP4D (Shared Information Platform for Disaster Management) as a core unified platform for public-private data acquisition, sharing, analysis and distribution. SIP4D is one of the national projects established to realize science and technology innovation, led by the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation, Cabinet Office, with management that transcends the boundaries of government ministries and old fields. The SIP4D aims at coordinating among different government departments as well as the private sectors and civil society to enhance efficiency and reduce redundancy for disaster management [28]. Thus, the Digital Agency and Society 5.0 bring a new dimension and hope for the open governance in Japanese society, wherein disaster prevention and mitigation are specially recognized as a priority. The key features of DRR under Society 5.0 will be optimized information for evacuation, search and rescue, which will enhance its efficiency. Robotics play an important role in search and rescue when it is combined with the information provided by other emerging technologies, like drones and big data analysis through AI. Quick damage estimation is also one of the key future focus areas, which will be linked to rapid decision-making during the disaster event. The AI-based analysis will be helpful for evacuation, especially targetting the aged and vulnerable groups [29]. The use of drones will be useful for damage assessment as well as for rescue operations. Correspondingly, a new initiative has also been started, which is supported by the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI) Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP) “Enhancement of Social Resiliency against Natural Disasters” [30]. Based on the “sharing of related information (resilience information network)”, effective disaster relief is a major goal in protecting Japan from future large-scale natural disasters, securing peace of mind and safety, and promoting the international presence and industrial power of our country. Seven tasks are envisioned to contribute to the three areas of prediction (to foresee and identify disasters), prevention (to develop liquefaction countermeasure to withstand disasters), and response (to minimize damage when a disaster occurs). Focusing on prediction, prevention and response, the SIP program aims to promote a new paradigm shift of DRR 4.0 under Society 5.0. In regards to that, Ref. [31] has made the first attempt to link DRR and CCA under the Society 5.0, and has linked it to the key sectors identified as priority sectors under climate change adaptation plans.

This evolutionary change in DRR 1.0 to 4.0 has also been demonstrated in the evolution of the DRR education as well, which has started from a science base to community participation to emphasise multi-hazards issues to bring DRR into daily lifestyles as well as to link to broader economic, political and social contexts [32]. Japan is possibly one of the few countries where the DRR issue becomes a point of discussion during political debates at times of election. Noticeably, the development of a specialized agency for disaster management or integrating disaster issues in different ministries and sectors through having it under the Cabinet Office has been a long political debate in Japan.

5. Society 5.0 and New Technology Regime in Japan

Japan is now becoming a transition country with several demographic issues, such as aged population, low birth rate, and depopulation in rural areas. Risks arising from climate change and disasters are further intensifying these concerns. To address these demographic changes, the Cabinet Office of Japan has announced the concept of Society 5.0 in its fifth Science and Technology Basic Plan in 2016 [33]. Herein, Society 5.0 is defined as: “A human-centered society (Society) that achieves both economic development and resolution of social issues through a system that highly integrates cyberspace (virtual space) and physical space (real space).” In that context, the previous societies have evolved in the following forms, as Hunting society (Society 1.0), Agricultural society (Society 2.0), Industrial society (Society 3.0), and Information society (Society 4.0). Although Society 4.0 is called an information society, the use of information in different sectors is faced with unique challenges and divides, based on age and gender. Thus, Society 5.0 aims to break the digital and information barriers, and enhance the ease of lifestyle at the core of society [34]. To realize the concept of Society 5.0, the business federation has come out strongly to utilize emerging and new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), drones, automated vehicles, and robotics putting information, as the core of the community [35].

Four megatrends are considered for the creation of Society 5.0, namely, digital transformation (DX), changes in the socio-economic structure, global environmental issues, and shifts in people’s mindsets. It is critical to turn the megatrend into opportunities for the realization of Society 5.0, the evolution of ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investment, which can also lead to the swift and reliable achievement of the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) [34]. Further, five figures which underline the characteristics of Society 5.0 are recognized in the analysis: “value creation” society, “diversity” society, “decentralized society”, “resilient society”, and “harmony with nature” society.” The business community (e.g., Keidanren) has strongly committed to “co-creation” of Society 5.0, by looking at the link of Society 5.0 and SDG as a future business and R&D opportunity [36]. Aiming to realize harmony of human and nature, Society 5.0 will have the following core emphasis: (1) Cities and Regions: Decentralized communities will be created in suburbs and rural areas, (2) Disaster Prevention and Mitigation: Sharing disaster information across organizations will facilitate swift responses to disasters, (3) Finance: Financial systems will allocate funds efficiently and effectively across society and (4) Public Services: Safety nets established by governments will enable anyone to tackle a variety of challenges with security. The “co-creation” of society also exemplifies concrete social images of energy, healthcare, agriculture/food, logistics, manufacturing/service.

After the notion of ‘Society 5.0’ was proposed in 2016, on 1 September 2021, Japan established its Digital Agency, which contributes to reforming the culture of administration in a user-driven manner through digitalization. The Digital Agency is intended to bring administrative reforms in the bureaucracy and governance, as it cuts across all ministries and agencies with a digital axis, with an aim to provide services that are driven not toward ministries, agencies, laws, or systems, but toward users and to improve user-experience. The Digital Agency represents a unique combination of public, private and semi-private organizations to serve the people in the most effective way. Within FY2021, Digital Agency aims at: (1) setting up a service which addresses core social problems, (2) settting up data standards and related rules and guidelines, and (3) identifying relevant human resources. This will faciliatate the digital drive and enhance data coordination [28]. Additionally, there are several sectors with immediate focus, such as: health, healthcare, education, disaster management, mobility, agriculture/fisheries, port and infrastructures.

6. Open Data Usage after DRR 3.0

As mentioned previously, the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami were one of the turning points for open data movement in Japan. Since then, the open data concept has gained momentum, and disaster prevention information is considered to be the most suitable genre for data disclosure. Before that, there was also a disaster response effort using OpenStreetMap, and the sinsai.info disaster-related information sharing site was launched using Ushahidi, which was used to map the damage caused by the 2010 earthquake and subsequent tsunami off the coast of Haiti [37]. Likewise, after the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, Safecast was established to collect and share accurate environmental data in an open and participatory way, which soon began monitoring, collecting and publishing information on the environmental radiation, rapidly expanding in scale, scope, and geographic coverage [38]. In addition, citizens, mainly engineers, launched Hack for Japan to support the development of applications and services to help and rebuild the disaster victims. On the Internet, several ideas were posted, and support application development took place [39]. Since then, many idea-thons and hackathons for disaster prevention and mitigation have also been held by governments and companies, as development and support activities continue.

In one of these cases, at the 2014 World Bank-sponsored Disaster Prevention Hackathon, a prototype of SHEREPO was proposed. This is a tool for evacuation shelter information application that intuitively and quickly extracts an evacuation shelter information index (based on water, food, living environment, and health hazards) and immediately visualizes it on an Open Street Map. This platform was created for Japan and the Philippines. In relation to this tool, Ref [40] summarizes the key challenges of information issues as follows: (1) the challenges of pre-disaster information due to displacement of people during disaster events, (2) uncertain IT infrastructure, (3) inability to confirm the accessibility of information and data, (4) inability to visualize the insights of social welfare of residents, (5) simultaneous display of information with time differences, (6) discrimination of information duplication, (7) ensuring reliability and validity, (8) setting cross-cut points for reporting information, (9) overlooking the issues related to vulnerable situations and people, and (10) not reporting the progress of improvements. While recognizing these factors, it was found to be important to generate information that can be used for decision-making and subsequent analysis of responses and instructions [41].

In 2016, the Basic Law on Public and Private Data Promotion was enacted to comprehensively and effectively promote the use of public and private data, thereby contributing to the realization of a safe and secure society and comfortable living environment for the public. The number of individual baseline data and research data for the indicators of the new global agenda is increasing, and the cross-disciplinary databases and disaster prevention models are being developed across meteorological, geological, civil engineering, social and health fields. The number of possible natural, scientific and technological measures has also increased. With the advancement of information and communication technologies (ICT), such as the establishment of a system for information sharing and utilization based on big data, it has become possible to construct people’s knowledge systems and activities with new technologies, and the types and means of disaster information available in the medium to long term and in real-time before and after disasters have increased remarkably. It now seems that it is necessary to organize useful information from miscellaneous and excessive information to overcome the lack of information. In addition, in the field of Evidence-Based Policy Making (EBPM), it has been recommended that local data should be analyzed and processed efficiently, and that both service providers and recipients should be able to obtain information and receive administrative services autonomously, rather than based on empirical measurements.

In 2016, the website of the Geospatial Information Center opened, providing a one-stop service for searching and obtaining geospatial and related information maintained by various entities for various purposes [42]. The year 2017 further saw the Cabinet’s approval of the new Basic Plan for the Promotion of Geospatial Information Utilization [43]. The plan outlines the goals of contributing to the formation of a disaster-resilient and sustainable land area, and contributing to a safe, secure, and high-quality life in a society with a declining and aging population by realizing a world-class G-spatial society, that utilizes advanced technologies such as IoT, big data, and AI [44]. At times of a disaster, common understanding through location information on maps will accordingly lead to accurate information sharing. As a basis for multi-organizational cooperation, reporting on information sharing systems using GIS (Geographic Information Systems) is also considered to be effective in terms of centralization and visualization of changes over time. If the communication environment permits, reporting with photos or videos of the situation can lead to a dramatic increase in confirmation and understanding of the situation [45].

In the aftermath of the flood in Mabi, Kurashiki on 6–7 July 2018, the city government made an attempt to use open GIS linked with drone survey to provide updates on the disaster damage to the public [46]. The organization of a research team for the use of GIS systems made it possible to systematically and continuously provide disaster-related information using GIS. As for the results of the damage assessment survey, the estimated inundation height was obtained using GIS and other technologies by setting the area for total destruction. This was extremely useful for the city government to reduce the time of damage assessment and is considered as the first use of the open data for open governance in a post-disaster situation, and is also considered as one of the key lessons from the West Japan flood [47]. On the other hand, citizens collaborated with Open Street Map’s Crisis Mappers and local Civic Tech to create a quick way to disseminate the information gathered from people in order to recover and rebuild the affected areas [48]. Information on the status of emergency support and opening of pharmacies, restaurants, convenience stores, and toilets were also shared using the Mabi Care platform. This set of information was crucial for the local residents immediately after the disaster. However, it was found that there were data distortions, variations, and duplication, while it was also difficult to reach the evacuees outside the designated evacuation centers. The city of Kurashiki then used Mabi Care as a tool to define the contents and format of data and align it so that customized information can be shared [49]. The city decided to prepare the data as open data during normal time, so that it can be used during the disaster, and a new platform called “Machi Care” was launched, where citizens can utilize the data and also expand it to a wide area [50,51].

In 2019, when typhoon Hagibis hit Nagano and Chiba, Machi Care was also used as a tool for volunteers to provide support information. At that time, items such as charging spots, Wi-Fi spots, available medical facilities, home centers, bathrooms, toilets, and disaster garbage collection sites were added [52]. By creating “open data” based on actual cases and releasing definitions and sample data, the system was quickly deployed in other areas. By releasing the data, new issues were discovered and brushed up, leading to new social businesses [53].

From the above analysis, how the 2011 East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami was one of the turning points for Japan’s DRR initiatives is corroborated, when Japan entered the DRR 4.0 phase. The need for customized and open information in normal time was felt for use during the disaster situation. However, it was only in 2018 that a specific initiative was undertaken, although many efforts started to incorporate the lessons learned from previous disasters. The West Japan flood of 2018 was another turning point when the open data system was actually used through civil tech initiatives, and gradually used by the government in the affected areas as well as other cities and municipalities.

7. Shizuoka Landslides and Open Data Usage

In relation to the key points of literature review and the concept that emerged above, a specific case study was conducted in the search for the fact and to explain the phenomenon that exists [15]. The aim of the case study was to address some of the following issues: (1) how the social collaboration and open governance emerged in an open data initiative and open governance at the time of the disaster, (2) how the team was formed at an early stage of response through social networking, and (3) what are the pros, cons and obstacles to facilitate the open governance for disaster risk reduction.

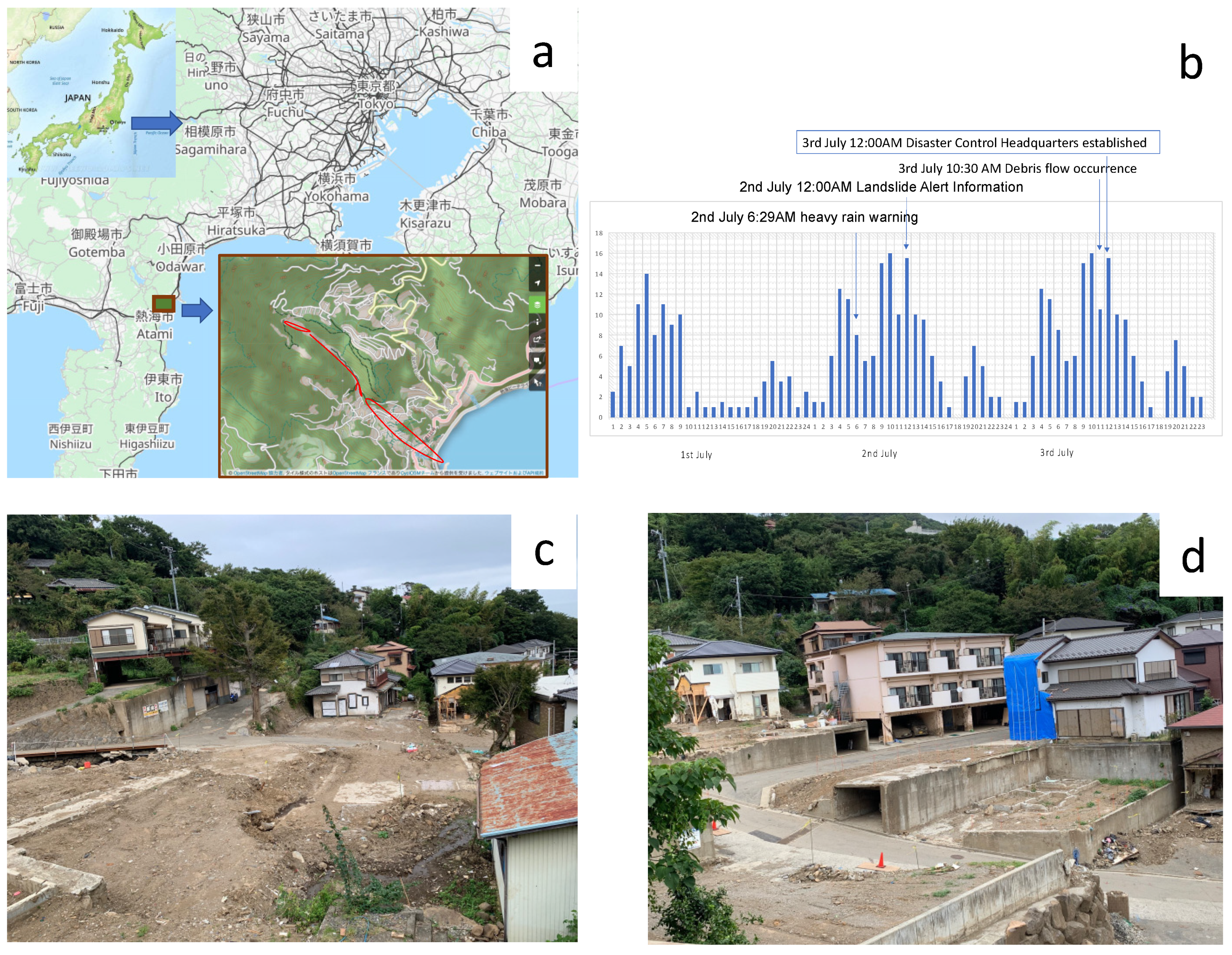

Towards the end of June 2021, a rainy season front moved northward and stalled in western and eastern Japan. Warm and humid air flowed toward the front one after another, making the atmospheric conditions extremely unstable, which resulted in record-breaking heavy rainfall, mainly in the Tokai and southern Kanto regions. The rainfall was unprecedented, with several locations in Shizuoka Prefecture having the highest 72-h rainfall (819 mm) ever recorded with the highest hourly rainfall of 58 mm in some areas. The heavy rains caused mudslides in Atami City, Shizuoka Prefecture, as well as swelling rivers and flooding in low-lying areas (JMA 2021 [54]). On 3rd July, around 10:30 a.m., the mudslide that occurred in the Izusan area of Atami City started at the head of the Ohatsu River at an elevation of about 390 m (about 2 km upstream from the coast) and flowed down the Ohatsu River, resulting in 26 life losses, one missing and three injuries. In total, 128 buildings were damaged. The area affected by the mudslide was approximately 1 km in length and 120 m in width [55,56]. Figure 1 shows the location map of the landslide disaster (a), rainfall pattern (b), and damage to residential houses (c), (d).

Figure 1.

(a) Location map, (b) rainfall distribution over time, (c,d) damages of houses.

On the administrative side, after the landslide at 10:30 a.m., the prefectural disaster countermeasures headquarters were established at 12:00 noon, and a request for dispatch of the Self-Defense Forces was made. At 13:30 p.m., a request to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency to dispatch an emergency firefighting aid team was made, and at 15:30 a Public announcement of the application of the Disaster Relief Act was announced. Firefighters were dispatched at 10:28 a.m. after receiving a report from a resident in the Izusan area that a house across the street was buried under mud and sand. The information spread quickly and widely through social networking services, as a video of the firefighters almost being caught in the mudslide was posted on Twitter and picked up overseas. As of 14 September, 115 people from 60 households had evacuated to a hotel, and on 15 September, the hotel was closed for use. Of the evacuees, 74 people from 35 households had not yet found a place to stay or had not completed the necessary procedures, so the city secured another hotel [57].

From 2019, there was an initiative called “Virtual Shizuoka”, which is a digital twin development plan being promoted by the Shizuoka Prefecture. The main target area is the eastern part of the Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture, where land and buildings in the prefecture are scanned in 3D and released as “point cloud data” for open use. The data were usually used for various purposes, such as improving the efficiency of infrastructure management (roads, rivers etc.), disaster recovery work, automatic driving initiatives to secure means of transportation in areas with a high ageing population, and promotion of tourism (geoparks and others). In accordance with Shizuoka Prefecture’s policy, the data have been released as open data on the G-Space platform [58]. Originally, the prefecture was promoting construction projects that utilize ICT, such as 3D surveying using drones and terrestrial laser scanners, an online preview of point cloud data, and construction using ICT equipment with machine control technology. The Geospatial Information Center has made the data measured by local governments available for free secondary use [59,60].

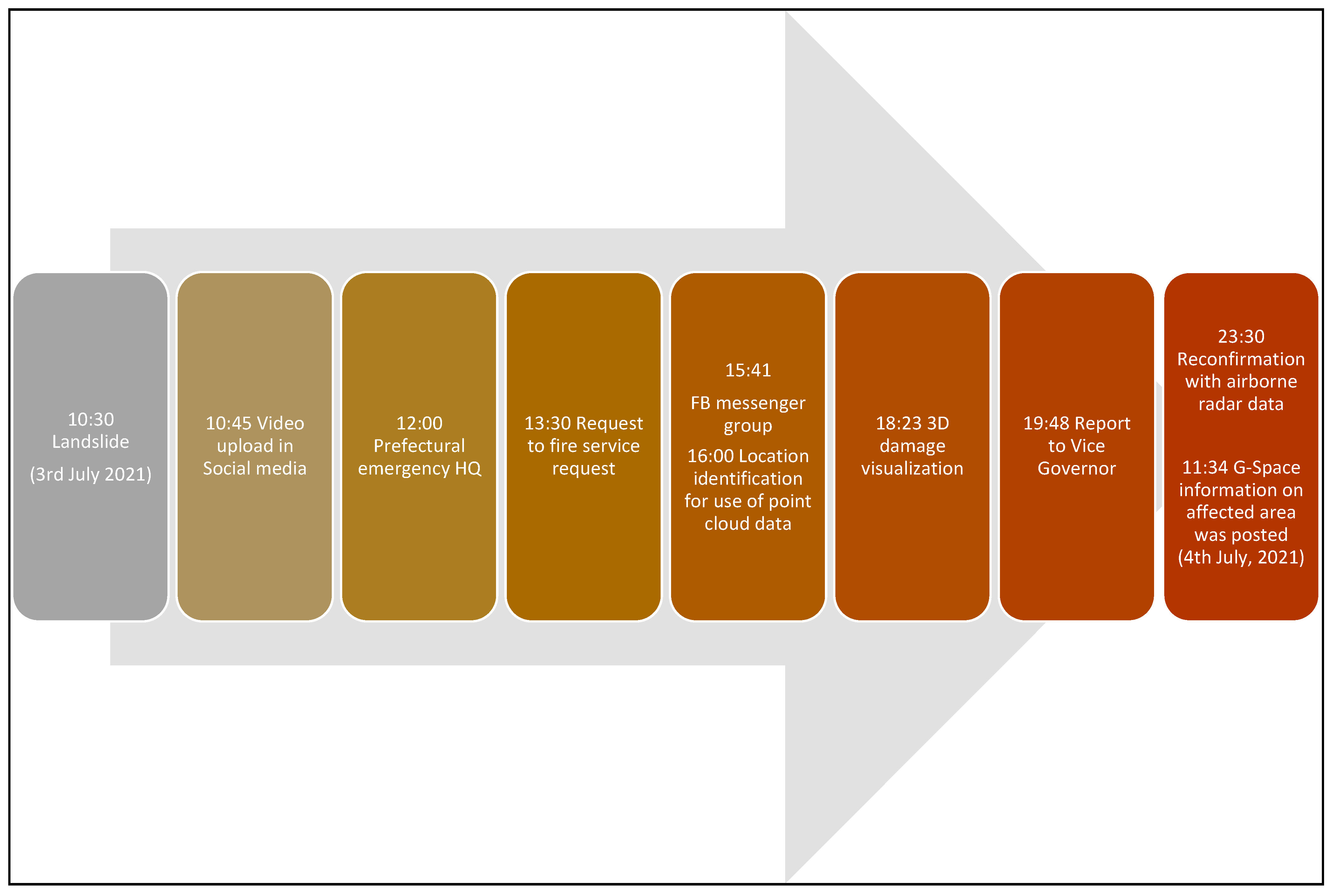

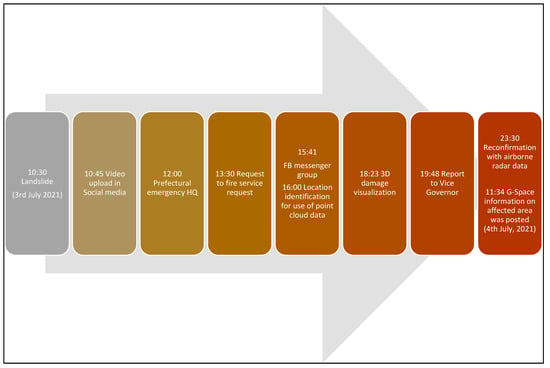

Figure 2 shows the chronology of different decisions after the disaster event, especially on the use of point cloud data [61]. As can be seen from the chronology that within four hours from the establishment of the social media group, the damage assessment and 3D maps were prepared, and reported to the Vice Governor. It was done by a team of five people including two professionals from the prefecture office, and three from the tech companies and academia. Originally, the data were meant for the prefectural government’s civil engineering work, and the team had assumed that the data could be used after a disaster, but what the team had assumed was that if a road slope collapsed, it would be useful for quick recovery by comparing the data with what the terrain looked like originally. In the immediate aftermath of the mudslide, the images were still being shared. The exact location and scale of the mudslide were not yet known, in light of which the team utilized the the point cloud data to identify the locations and estimate the damage [62].

Figure 2.

Chronological events of use of Point Cloud Data for damage assessment.

As a result of the field observations and lessons from the Shizuoka landslide case, the previously mentioned five principles of open data in the DRR field can be analyzed as follows: (1) open by default, (2) accessible, licensed and documented, (3) co-created, (4) locally owned, and (5) communicated in ways that meet the needs of diverse users.

- (1)

- Open by default: In Japan, the Basic Law and Basic Plan for the Promotion of Public-Private Data Utilization have been in effect since 2016, wherein the basic idea is that government data should be open. Originally, Shizuoka prefecture created the catalog site and handled the point cloud data as part of that process. Each department was looking at past disasters to see what their field could do better. As a result, they had the mindset that it should be open data, and it was easy to understand. Additionally, since the prefecture was always communicating with users on a daily basis, the data administration was able to quickly make the final decision on the conversion to open data (upload, download method, data aggregation destination).

- (2)

- Accessible, licensed and documented: Shizuoka Prefecture had made it CC BY4.0 open data, so various companies were able to use it. As a result, the private tech firms were able to obtain a wide variety of data, some of which were taken with 4K camera drone data and made available to the public. On the other hand, some were concerned that the data taken by the mass media might be trapped by copyright.

- (3)

- Co-created: The team members in this project were familiar with using a variety of tools in their daily work. It is important to be able to use the tools that are normally available when collaborating. Using Zoom, the team was able to share the screen using a browser and discuss using the messenger. The tech company provided a remote desktop connection to their servers so that the 3D data from the point cloud could be viewed immediately. Thus, the co-creation was done by the local government, academic and tech company.

- (4)

- Locally owned: When collaborating within the government, activities may usually be limited to those within the LGWAN (Local General Government Wide Area Network). Since the network is designed to be essentially closed for security purposes, it is difficult to communicate with the outside world quickly or handle large amounts of data. It must be used under highly secure conditions. It is important that the local government has an Internet machine for emergency use. Since there were no restrictions on the tools used in academic research sites, there was no limit to the tools, but it is rather important to know how well such tools can be used in practice. There is an email address for administrative staff in local government, but even if one receives an email there, it cannot be automatically forwarded to one’s personal terminal. This time, some officers tried to use their iPad to send an email to the prefecture, but it was blocked. As a result, the responsible officer solved the problem by sending it using his personal address. Thus, a locally owned system with proper security is considered to be important.

- (5)

- Communicated in ways that meet the needs of diverse users: The flow of information in society, including SNS, is faster. However, the problem is how to handle it. Only what people use on a daily basis is useful in the field. If there are people who do not understand, the work will stop there. It is rare to have a situation like this. In this case, the use of familiar social media such as Facebook and Twitter was used extensively.

8. Potentials and Challenges of Open Governance

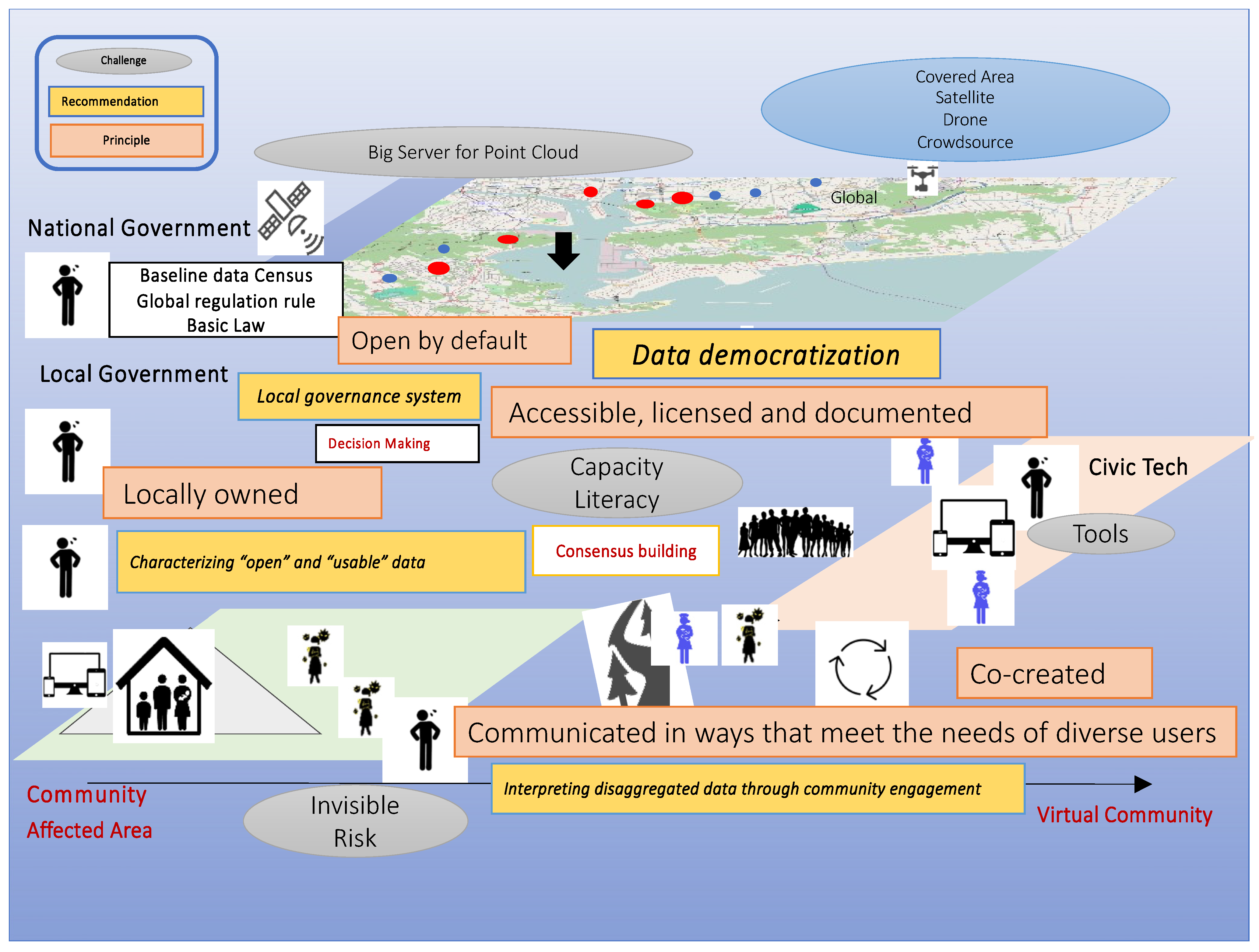

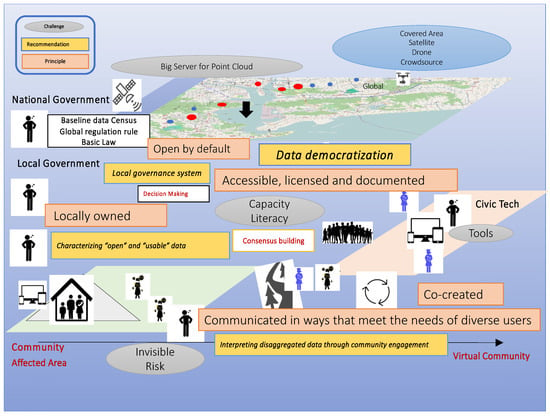

Based on the lessons derived through the review of existing literature, field survey, interviews and analysis of the Shizuoka case, the following five generalized lessons can be drawn for enhancing the effective use of open data for open governance in the DRR field as well as disaster response and recovery. Figure 3 illustrates the concepts, challenges and potentials of use of open data and open governance.

Figure 3.

Conceptual diagram, potentials and challenges of the use of open data for open governance.

- (1)

- Characterizing “open” and “usable” data: Since the DRR 3.0 era, Japan has promoted “data utilization” and “digital government” as the pillars of its strategy through the establishment of the Government CIO (Chief Information Officer) and the enactment of the Public-Private Data Basic Act. It has also been noted that Shizuoka prefecture complies and promotes open data in normal times, due to which it could use the accumulated data in emergency situations. However, the utilization of data has not progressed sufficiently in Japan due to low data literacy and strong concerns about privacy. According to the “Survey and Research on Consumer Attitudes toward the Data Distribution Environment” [63], variation in data formats and quality assurance are cited as critical issues in the use of digital data. In most cases, fundamental data of government are open as a pdf file, due to which it is difficult to use them as specific data for analysis. Furthermore, the information on damage caused by the disasters includes, among others, damage to public infrastructures such as electricity, water, gas, telecommunications, transportation [64], information on follow-up fires and industrial accidents (NATECH: natural hazard induced technological disasters), and evacuation and displacement of people [65]. It is anticipated that the progress in the use of public data by a wide range of entities can help solve various issues through the promotion of public participation and public-private collaboration. Improving the quality of the data shall also lead to its effective utilization. There is a clear demarcation of “open” and “usable” data in DRR, wherein it is recommended to use a customized data format to make it usable during and after the disaster. After the Kurashiki case described above, at the Open Data Utilization Roundtable, on the theme of disaster prevention, recommended datasets are mentioned that could be useful for disaster prevention, if prepared in advance. Following the government’s recommended data sets, and having published them with recommended templates, it should be reviewed and customized based on local risk [66]. To facilitate a variety of subsequent analysis with emerging technology, standard metadata for time, location and attributes, which are fundamental to epidemiology, must also be available.

- (2)

- Local governance system: It is important to develop the local governance system for open data. While during the COVID-19 pandemic times, the direct visits to offices have been restricted to maintain social distancing; it could address the importance of the data cloud, which can be remotely accessed. This thought has led to towards a mindset change of the local governments. Initially, the environment was visualized to be like a large room where data to be collected and information to be disseminated can be centrally managed and scrutinized based on analysis and decision-making needs. However, as the open data does not need a specific expertise in the local government, starting point and consensus-building becomes critical. By displaying the data spatially and looking at differences from normal times and from region to region to improve the fairness of future support, and by looking at fixed point data from various groups over time, it has now become possible to confirm differences in change. Herein, data licensing is a critical part of open local governance, which enables the outside stakeholders to use the data and be part of the analytical team. It is important to have a dual license (Open Database License: ODbL, Creative Commons: CC BY 4.0) and other similar multiple licenses. It is also urgent to set up the platform to carry out rapid and accurate activities with the goal of saving lives and reducing disasters in a safe area [67]. In light of these potentials, local governance holds great promises in the changing risk landscape on all-hazard approaches.

- (3)

- Co-creation to co-delivery: It is vital to have partnerships in data sharing, data analysis and data interpretation. Human resources become critical, and the common use of protocols (like similar communication platforms) is important. In the Shizuoka case, it has been noted how the government officers often worked with civic tech companies. They could connect online and create the data with limited members. Citizen participation thus becomes critical in co-delivery, though main findings of field works are that co-creation is mostly initiated by non-governmental actors, and that most local governments have neutral or even negative attitudes towards co-creation. It is the reason why the digital divide remains vulnerable to disaster since DRR 2.0. To extend to human (vulnerable people)-centered DRR, it is required to take ownership of the problem and communication. It is also important to keep in mind that although communication via the Internet is quick, it is a method that tends to overlook important information. Some information can be obtained more quickly through SNS such as Twitter. The easiest way is to set a place to listen to the voices of people in the field. The latest consensus should be identified using emerging technology on information sharing, people and data. It is required to develop an enabling environment and human resources capable of responding to it.

- (4)

- Data democratization: This is an important vision for the open data ecosystem. In most cases, the data are concentrated to a specific institution/company, which prohibits the free use of data by other users as well as updating the databases. Any changes in data require technical expertise, which is mostly available to the host institution. In that context, data democratization can be defined as “making digital information accessible to the average non-technical user of information systems, without having to require the involvement of IT” [68]. The grassroots approach of data management increases the data users to non-specialist groups. The more one uses democratized data, the more it becomes user-friendly, and can be used for open governance, and is linked to a better data ecosystem [69]. On the other hand, the lack of data storage and the limited understanding of access in a culture of closed data can violate people’s privacy and lead to misuse and misinterpretation of data. Further, even highly reliable open data can contain erroneous data, which raise concerns of misinterpretation and disadvantages on consensus building. It is therefore important to constantly improve the accuracy of data. When data are combined and analyzed, new problems and vulnerabilities may be highlighted. It is also necessary to consider how to deal with the situation if it leads to something unintended. Combining accumulated knowledge of the community and academic field makes it possible to conduct activities to make the data and knowledge open in an efficient, scientific and ethical manner. Preparing the data into items by departmental resources accountable for human casualties and property damage can make governance easier to track, manage, and update.

- (5)

- Interpreting disaggregated data through community engagement: It is required for citizens to work together with the government, businesses, and NPOs to co-create and co-interpret data, especially when it is desegregated based on age, sex, occupation, physical and mental soundness, nationality, etc. Gathering information from inside the community, where there are barriers to information such as physical isolation, technological communication breakdown, and linguistic inability to hear or read varies greatly depending on the information provider and listener, and is also difficult to share. Hence, citizen participation in data collection and management becomes critical. Although citizen science is popular in other fields such as biodiversity or environmental management, it needs a proper platform and incentive mechanism to upscale in the DRR field. Grassroots problem-solving using social networking sites and other forms of communication that residents use on a daily basis, such as web forms to confirm each other’s safety quickly, can also be seen as a way to connect with the broader community. The non-verbal insights observed in the communication between vulnerable people and those whose last mile is connected are also of importance, as well as the responsiveness of being aware of and respecting the gender, position, crisis, and vulnerability of others, and protecting them before they are subsequently exposed to danger. Thus, it is required to raise literacy to be able to make decisions for risk reduction and appropriate recovery that exist in normal times. A place to listen to the voices of people in the field is very much required.

9. Conclusions

Based on the case study analysis and literature review, the following key conclusions can be derived for the effective use of open data and open governance in DRR.

The case of Shizuoka, as described in the paper, illustrates the respective needs of each group and how the data can be shared. In that way, one can avoid the duplication of efforts and address the needs of the organizations. Local government bodies need to accordingly strengthen their capacities. Science and technology can help towns and cities run more efficiently on a day-to-day basis. It is not an advocacy for investing more funds in complex infrastructure. Instead, even if the fund is not available, the data collected on everyday aspects such as traffic, public works, and public health can be used to save lives in a crisis situation and there are ways to be more successful using the already existing capabilities.

Open data is a common tool for information communication through a coordinated approach. While there has been success in making open data for geo-spatial information, as learned from the case study analysis, it is important to have customized open data for people, wellbeing, and health care to reduce persisting vulnerability. An essential step in preparing open data is to know which data must be shared and which data must be protected to ensure that no one will be left behind. Due to privacy issues, sensitive data can be shared among government agencies but not outside the government. It is essential to define the boundaries and have a data usage and license in place to be used, as and when needed.

The local government’s role as the critical platform is important to use the data and analysis for rapid response and decision-making during, before and after a disaster. It should prepare a standardized platform to share the data they collect (e.g., road conditions, geomorphological, demographic and infrastructure data) with the state and other organizations. Trusted partnership and transparency in data sharing becomes important. It needs a cultural shift in the governance mechanism with proper balance of privacy and security of data, eventually making it more accessible for the critical case during an emergency, in case they may not have enough capacity. Moreover, open governance is still an evolving culture which takes time to transform, because it is difficult to understand its essential social behavior and norms in daily life that become critical in the time of disaster. It should make the most of this favorable opportunity to address both legal and technical challenges in an accelerated digitalization process and paradigm change of disaster management during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Open governance can help community-based DRR, especially a human-centered approach which is more efficient on a day-to-day basis. It is not an advocacy for investing more funds in hard infrastructure. Rather, even if the funds are not available, data collected on everyday aspects such as traffic, public works, and public health can be used to save lives in a crisis situation. This can ensure success using the already existing capabilities.

In conclusion, open governance needs a cultural shift in the governance mechanism with the proper balance of privacy and security of information, and making it more accessible during an emergency. It is very important to properly synchronize and customize open data, open governance and emerging/disruptive technologies for its effective use in DRR. The evolution of emerging technologies and their usage is presently going at a higher speed than ever. During the emergency, community needs communication tools and platforms to co-deliver including risk communication, consensus-building and coordination. Transparency, ownership, citizen and stakeholder participation in data gathering, management, analysis and interpretation become crucial. Local government’s role is important to use the data and analysis for rapid response as well as decision-making during, before and after a disaster. These findings are also useful for societies outside Japan, especially in terms of data issues and licensing, adaptive governance, stakeholder usage and community emngagment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and R.S.; Methodology, S.K. and R.S.; formal analysis, S.K. and R.S.; writing- orginal draft preparation S.K. and R.S.; editing, S.K. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP 18H03120 to S.K. and Fukuzawa Research Fund from Keio University to R.S.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the discussion with Naoya Sugimoto of Shizuoka prefecture and Shogo Numakura of Symmetry for their inputs on the contents of the case study. R.S. acknowledges support from the Fukuzawa Research Fund of Keio University. S.K. acknowledges support by JSPS KAKENHI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tierney, K. Disaster governance: Social, political and economic dimensions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 37, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N. The state of the discipline of public administration: The future is promising. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Garayev, V. Collaborative decision-making in emergency and disaster management. Int. J. Public Adm. 2011, 34, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, E.; Ray-Bennett, N. Disaster risk governance for district-level landslide risk management in Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 59, 102220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forino, G.; Meding, J.; Brewer, G. A conceptual governance framework for climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction integration. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2015, 6, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djlante, R.; Luwasa, S. Governing complexities and its implication on the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction priority 2 on governance. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2019, 2, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Open Government: The Global Context and the Way Forward. 2016. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/gov/open-government-9789264268104-en.htm (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Putnam, R.D. Turning in and tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. Political Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.; Birkmeyer, S. Open government: Origin, development and conceptual perspectives. Int. J. Public Adm. 2015, 38, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. Open Government: Helping Citizen Engaging with Governments. 2021. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/projects/open-governance-helping-citizens-engage-with-government (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- OCED. OECD Handbook on Information, Consultation and Public Participation. 2011. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/citizens-as-partners_9789264195578-en (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Meijer, A.J.; Lips, M.; Chen, K. Open governance: A new paradigm for understanding urban governance in an information age. Front. Sustain. Cities 2019, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidi, H.; Taleai, M.; Yan, W.; Shaw, R. Digital citizen science for responding to COVID-19 crisis: Experiences from Iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensaiinfo. Report on the Community Workshop of the Office for Promotion of National Spatial Resilience, Cabinet Secretariat. 2016. Available online: https://www.gensaiinfo.com/blog/2016/1128/7822 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case study methods. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bikker, A.P.; Atherton, H.; Brant, H. Conducting a team-based multi-sited focused ethnography in primary care. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, T.L. Basic classical ethnographic research methods. Cult. Ecol. Health Chang. 2005, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, A. The Value of Open Governance, Adaptive Learning and Development. 2016. Available online: https://www.globalintegrity.org/2016/01/21/the-value-of-open-governance-adaptive-learning-and-development/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Yao, K. Open Government Data for Disaster Risk Reduction, in Bangkok, Thailand. 2016. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/OGD%20for%20DRM0308.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- UN DESA. Guidelines on Open Government Data for Citizen Engagement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013; 104p. [Google Scholar]

- SP-OGD. Open Government Data Definition: The Eight Principles of Open Government Data. 2007. Available online: https://opengovdata.io/2014/8-principles/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Open DRI. Available online: https://opendri.org (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Cabinet Office Japan. Disaster Risk Reduction 4.0: Future Concept Project. 2016. Available online: http://www.bousai.go.jp/kaigirep/kenkyu/miraikousou/index.html (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Cabinet Office Japan. White Paper on Disaster Management. 2006. Available online: http://www.bousai.go.jp/en/documentation/white_paper/index.html (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Sekiya, N. Anxiety and information behavior after the great East Japan earthquake. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 62, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, A.; Toriumi, F.; Komori, M.; Matsumura, M.; Hiraishi, K. Disaster information propagation and emotion in social media: A case study of the great East Japan earthquake. J. Jpn. Soc. Artif. Intell. 2015, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office Japan. Overview of Disaster Countermeasures Legislation. 2012. Available online: https://www.cao.go.jp/houan/doc/180-8gaiyou.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Digital Agency. Priority Policy Program for the Realization of a Digital Society. 2021. Available online: https://cio.go.jp/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/digital/20210901_en_04.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Nakajima, M. Strengthening Resilient Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Functions—Real-Time Sharing and Utilization of Disaster Information. 2016. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/gaiyo/sip/sympo1610/bousai.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021). (In Japanese).

- SIP. SIP: Changes the Approach of Disaster Prevention. 2016. Available online: https://www.jst.go.jp/sip/dl/k08/k08_vision_en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Mavrodieva, A.; Shaw, R. Disaster and Climate Change Issues in Japan’s Society 5.0. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, K. Continuity and Change in Disaster Education in Japan. Hist. Educ. 2015, 44, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office Japan. Cabinet Office 5th Science and Technology Basic Plan. 2016. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/kihonkeikaku/5honbun.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021). (In Japanese)

- Tegakari. Society 5.0 Accelerates R&D in Japan. 2020. Available online: https://www.tegakari.net/en/2020/07/society5_0/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Keidanren; University of Tokyo; JPIF. Toward the Evolution of ESG Investment, Realization of Society 5.0, and Achievement of SDGs—Promotion of Investment in Problem-Solving Innovation. 2020. Available online: https://www.gpif.go.jp/en/investment/Report_Society_and_SDGs_en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Keidanren. Revitalizing Japan by Realizing Society 5.0: Action Plan for Creating the Society of the Future Overview. 2017. Available online: http://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2017/010_overview.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Seto, T. Spatiotemporal transition of volunteered geographic information as a response to crisis: A case study of the crisis mapping project at the time of great East Japan earthquake. In Papers and Proceedings of the Geographic Information Systems Association; Reconstruction Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; Volume 20, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Coletti, M.; Hultquist, C.; Kennedy, W.G.; Cervone, G. Validating Safecast data by comparisons to a US Department of Energy Fukushima Prefecture aerial survey. J. Environ. Radioact. 2017, 171, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utani, A.; Mizumoto, T.; Okumura, T. How Geeks Responded to a Catastrophic Disaster of a High-Tech Country: Rapid Development of Counter-Disaster Systems for the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011. In Proceedings of the Special Workshop on Internet and Disasters, Tokyo, Japan, 6–9 December 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kanbara, S.; Estuar, M.R.J.E. Feasibility Study of Integrating Human Dimension and Human Security in a Disaster Management System: Integrating eBayanihan and SHEREPO. 2015. Available online: https://www.the-easia.org/jrp/pdf/w05/Kambara_Estuar.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Estuar, M.R.J.E.; Kanbara, S. S121: Integrating health and disaster. BMJ Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association for Promotion of Infrastructure Geospatial Information Distribution. Toward the Distribution and Business Creation of Various G-Spatial Information in Industry, Government and Academia. 2021. Available online: https://aigid.jp/?page_id=1785 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Cabinet Secretariat Japan. Basic Act on the Promotion of Public-Private Data Utilization. 2016. Available online: https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/singi/it2/hourei/detakatsuyo_honbun.html (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. What is the Basic Act and Basic Plan for the Promotion of Geospatial Information Utilization. 2017. Available online: https://www.gsi.go.jp/chirikukan/about_kihonhou.html (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Kanbara, S. EpiNurse: Participatory Monitoring of Health Security and Disaster Risk Reduction by Local Nurses. 2017. Available online: https://janet-dr.com/100_renkei/102_renkei/201706_SCAProgram.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Hara, T. Case Study of GIS Application in Kurashiki City Disaster Countermeasures Headquarters (Heavy Rainfall in July, 2008): Drone Aerial Photography for Flood Damage Assessment and House Damage Survey Activities. 2018. Available online: http://microgeodata.jp/contents/pdf/mgd14/mgd14_4.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021). (In Japanese).

- Das, S. Six Months since Western Japan Flood: Lessons from Mabi. 2019. Available online: https://www.cwsjapan.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Lessons-From-Mabi.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Mabi Care. Available online: https://mabi-care.com (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Data Cradle. Available online: Bousai-map.datacradle.jp (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Machi Care. Available online: https://machicare.jp (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Oshima, M.; Kanbara, S.; Sikanae, J.; Hara, T. Enhancing Information on Evacuation Centers and Building an Evacuation Planning Support System (the Future of “Mabicare”) Challenge Open Governance 2021. 2021. Available online: http://park.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/padit/cog2018/final/49_Idea_COG2018_presentation.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. ICT Regional Revitalization Award Disaster Prevention Portal “Machi-Care” using Open Data. 2019. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/joho_tsusin/top/local_support/ict/taisho/index.html (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Open Data 2.0. In Promoting Data Distribution through Public-Private Partnership: “Realizing” Open Data to Solve Problems.; 2016. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/johotsusintokei/whitepaper/eng/WP2020/chapter-6.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Japan Meteorological Agency: Heavy Rain due to Rainy Season Front. 2021. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/data/bosai/report/2021/20210708/20210708.html (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- NHK. Atami: “A Large Amount of Muddy Water Turned into a Mudslide Three Hours Later,” Filmed by a Woman near the Site. 2021. Available online: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20210709/k10013129851000.html (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Shizuoka Prefecture. Mudslide in Atami Izusan Area (36th Report). 2021. Available online: http://www.pref.shizuoka.jp/kinkyu/documents/atamidposya36.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- TV Shizuoka. Atami Mudslide: “Two and a Half Months Go by Quickly” as Evacuation Hotels Expire and People Move into New Homes. 2021. Available online: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/7326de11f9a4cb80eb8db4982a9819e9aeb55de5 (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Sugimoto, N. Shizuoka Prefecture Aims to Utilize 3D Data in the Near Future. 2019. Available online: https://www.zenken.com/kensyuu/kousyuukai/H31/659/659_sugimoto.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).