Sustainable Development of EFL/ESL Learners’ Willingness to Communicate: The Effects of Teachers and Teaching Styles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Relevant Literature

2.1. L2 Willingness to Communicate

2.1.1. Conceptualising the Construct of L2 WTC

2.1.2. WTC Inside and Outside Classrooms

2.1.3. Chinese English Learners’ Low WTC: Mute English

2.2. Teachers and Teaching Styles (TTS)

2.2.1. The Role of Teachers in L2 Pedagogy

2.2.2. The Role of Teaching Styles in L2 Pedagogy

2.3. The Effect of TTS on L2 WTC

2.3.1. Motivational Influences of TTS on L2 WTC

2.3.2. Affective–Cognitive Influences of TTS on L2 WTC

2.3.3. TTS in Broader Social Context

3. Research Questions

- (1)

- To what extent are Chinese English learners in mainland China and abroad willing to communicate in English inside and outside classrooms?

- (2)

- What are the attitudes of Chinese English learners studying in mainland China (domestic group) and abroad (abroad group) towards their teachers and teaching styles (TTS)?

- (3)

- To what extent do Chinese English learners’ attitudes towards TTS affect their L2 WTC inside and outside classrooms in each group?

- (4)

- Are there any differences in the influences of Chinese English learners’ attitudes towards TTS on their L2 WTC inside and outside classrooms between the two groups? If any, what are the possible reasons?

4. Method

4.1. Research Design

4.2. Participants

4.3. Instruments

4.4. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Findings from the Questionnaire Data

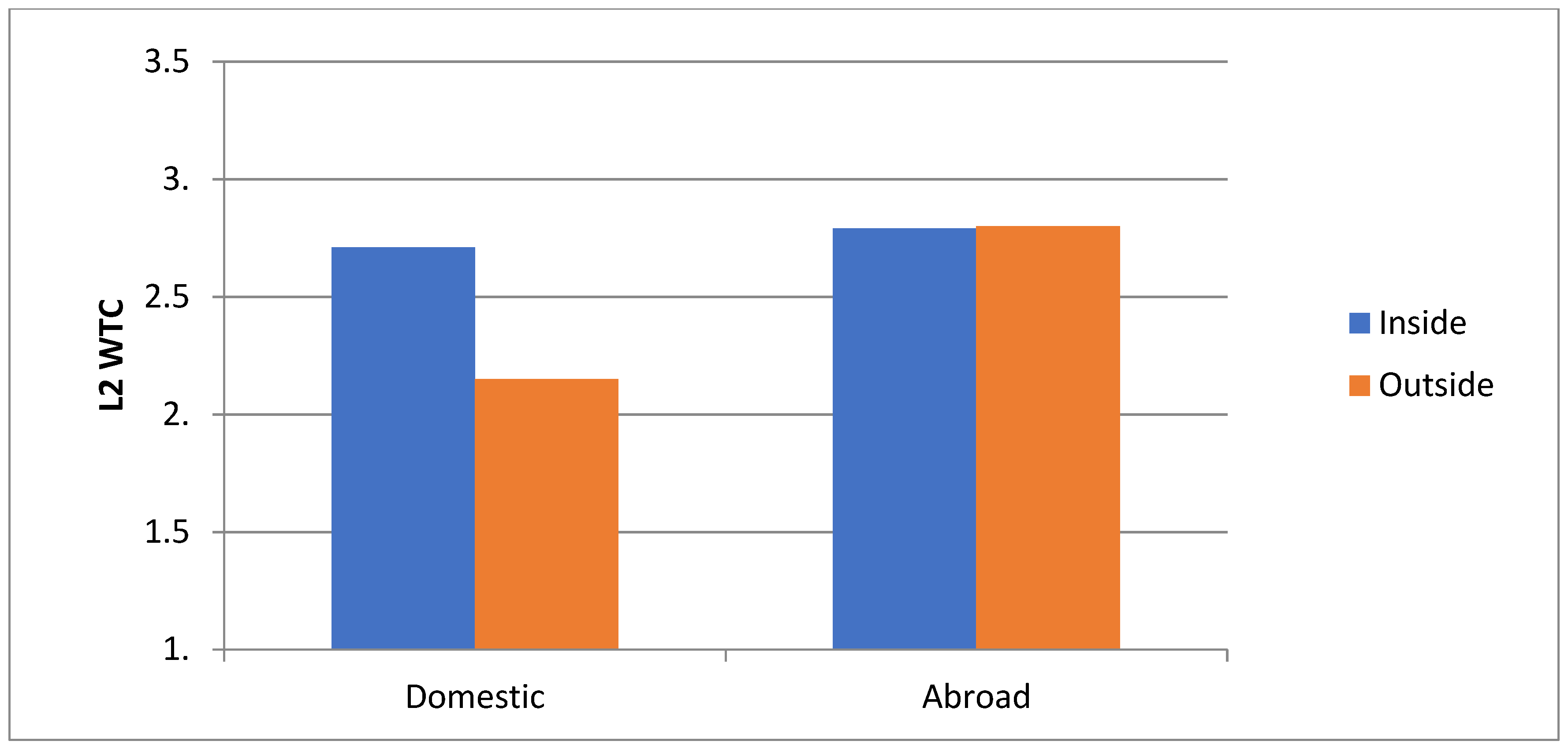

5.1.1. Chinese English Learners’ L2 WTC

5.1.2. TTS in Each Group

5.1.3. Relationship between TTS and L2 WTC

5.1.4. Significant Predictors of L2 WTC

5.2. Findings from the Interview Data

5.2.1. Relationship between TTS and L2 WTC in Both Groups

Zhao (male, 26): My English teacher tells jokes sometimes, but always in Chinese. We will laugh and feel relaxed, but the effect is almost gone immediately when we get back to English.

Zhang (male, 24): I didn’t realise that the teacher was joking until later. All I could see was my classmates’ laughing.

Chen (female, 23): She follows the textbook strictly. I could make preparations in advance. We always know what kind of questions she will ask. Most of the time, I answer her questions in the way she wants, mostly under obligation, not my free will.

5.2.2. Relationship between TTS and L2 WTC in the Domestic Group

Jia (female, 23): I like her, so I want to speak English more even outside classrooms because I am not afraid of making mistakes in front of her.Chen (female, 23): My English teacher is amazing. We think it’s charming for a person to speak English so fluently, and we want to be like her. So, we would grasp every opportunity to practice our English.

Sun (male, 24): It would be better for a teacher to dress formally. It shows that he/she is taking education and students seriously.Zhao (male, 26): Dressing too formally makes the teacher distant. I was usually too scared to talk in front of her.

5.2.3. Relationship between TTS and L2 WTC in the Abroad Group

Zhang (male, 24): My English teacher often makes gestures to us, and we could easily keep pace with her. Otherwise, I would probably feel too formal and would be less likely to communicate.

Ding (male, 21): It does not make any difference whether my English teacher makes any gesture in class or not.

6. Discussion

6.1. Chinese English Learners’ L2 WTC

6.2. Differences in the TTS of Both Groups

6.3. Relationship between TTS and L2 WTC

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Gender: female/male

- Age:

- Is your school: a secondary school/ university?

- Which languages do you know? (chronological order from birth; for your first language, L1, you can give more than one if you grew up in a multilingual family: L1a, L1b), by “knowing” I mean the ability to have at least a basic exchange in the language

- L1a____________

- L1b____________

- L1c____________

- L2____________

- L3____________

- L4____________

- L5____________

- Other languages (please specify)_______________

- Which English-speaking country are you studying English in?

- How long have you studied English in an English-speaking country? (In years)

- Have you ever lived in another English-speaking country? Yes/no

- If you have ever lived in another English-speaking country, how long?

- What is your attitude towards English? Very unfavourable, unfavourable, neutral, favourable, very favourable

- What was the result of your last major English test (in %)?

- How would you describe your English performance compared to the rest of the group in class? Far below average, below average, average, above average, far above average

- Would you describe yourself in your English as a: beginner, low intermediate, intermediate, high intermediate, advanced, very advanced

- What is your attitude towards your English teacher? (If you have several, focus on one only) (Very unfavourable, unfavourable, neutral, favourable, very favourable)

- What is your English teacher’s gender? (Female/male)

- What is your English teacher’s age? (Twenties, thirties, forties, fifties, sixties or older)

- How does your English teacher dress? (Very casually, casually, neutral, formally, very formally)

- How strict is your English teacher? (Not strict at all, a little strict, rather strict, strict, very strict)

- How friendly is your English teacher? (Very unfriendly, unfriendly, neutral, friendly, very friendly)

- How often does your English teacher joke in your English class? (Never, rarely, sometimes, regularly, very frequently)

- How often does your English teacher show concerns about your needs? (Never, rarely, sometimes, regularly, very frequently)

- How much does your English teacher enjoy interacting with students? (Never, little, somewhat, much, a great deal)

- How often does your English teacher use her/his hands and arms to gesture while talking to students? (Never, rarely, sometimes, regularly, very frequently)

- What kind of voice does your English teacher use while talking to students? (Very dull, slightly dull, neutral, slightly animated, very animated)

- How is your English teacher’s body position while talking to students? (Very tense, slightly tense, neutral, slightly relaxed, very relaxed)

- How far away does your English teacher stand or sit while talking to students? (Very far, slightly far, neutral, slightly close, very close)

- Is your teacher a native speaker of English? Yes/no/do not know

- How frequently does your teacher use English in class? (Hardly ever, not very often, sometimes, usually, all the time)

- How much class time with your teacher is spent on writing? (in %)

- How much class time with your teacher is spent on reading? (in %)

- How much class time with your teacher is spent on listening? (in %)

- How much class time with your teacher is spent on speaking? (in %)

- How predictable are your English teacher’s classes? (Very unpredictable, unpredictable, it varies, predictable, very predictable)

| Using English in Class | Almost Never Willing | Sometimes Willing | Willing Half of the Time | Usually Willing | Almost Always Willing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Speaking in a group about your holiday. | |||||

| 2. Speaking to your teacher about your homework. | |||||

| 3. You are confused about a task you must complete, how willing are you to ask for instructions/clarification? | |||||

| 4. Talking to a friend during class. | |||||

| 5. How willing would you be to be an actor in a play? | |||||

| 6. Describing the rules of your favourite game. | |||||

| 7. Playing a game in your English class. | |||||

| 8. Volunteering an answer/comment |

| Using English Outside the Class | Almost Never Willing | Sometimes Willing | Willing Half of the Time | Usually Willing | Almost Always Willing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Making a presentation in front of a large group. | |||||

| 2. Talking with an acquaintance while standing in line. | |||||

| 3. Talking with a salesperson in a store. | |||||

| 4. Talking in a small group of strangers. | |||||

| 5. Talking with a friend while standing in line. | |||||

| 6. Talking with a stranger while standing in line. | |||||

| 7. Talking in a small group of acquaintances. | |||||

| 8. Talking in a small group of friends. |

References

- Han, J.; Geng, X.; Wang, Q. Sustainable Development of University EFL Learners’ Engagement, Satisfaction, and Self-Efficacy in Online Learning Environments: Chinese Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.W.; Zhang, D.L.; Zhang, L.J. Metacognitive instruction for sustainable learning: Learners’ perceptions of task difficulty and use of metacognitive strategies in completing integrated speaking tasks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jämsä, T. Philosophy, perception and interpretation of concepts-The concept of sustainable education. In Education & Sustainable Development, First Steps toward Changes; Pipere, A., Ed.; Saule: Daugavpils, Latvia, 2006; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J.; Pae, T.I. Social psychological theories and sustainable second language learning: A model comparison approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baran-Łucarz, M. The mediating effect of culture on the relationship between FL self-assessment and L2 willingness to communicate: The Polish and Italian EFL context. In New Perspectives on Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language; Zarrinabadi, N., Pawlak, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 85–117. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.E. Willingness to Communicate in the Chinese EFL University Classroom; Multilingual Matters: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clément, R.; Baker, S.C.; MacIntyre, P.D. Willingness to communicate in a second language: The effects of context, norms, and vitality. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 22, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Doucette, J. Willingness to communicate and action control. System 2010, 38, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, M.D.; de los Ángeles Hidalgo, M. L1 use among young EFL mainstream and CLIL learners in task-supported interaction. System 2017, 67, 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, D. Teaching ESL versus EFL: Principles and practices. Bur. Educ. Cult. Aff. 2005, 43, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, N.; Sato, M. Comparing the same task in ESL vs. EFL learning contexts: An activity theory perspective. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2020, 30, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N.; Naganuma, N.; Data, B. Transition from learning English to learning in English: Students’ perceived adjustment difficulties in an English-medium university in Japan. Asian EFL J. 2006, 8, 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q. An emotional journey of change: The case of Chinese students in UK higher education. In Researching Chinese Learners: Skills, Perceptions & Intercultural Adaptation; Jin, L., Cortazzi, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011; pp. 212–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Y.; Hiver, P. Using a language socialization framework to explore Chinese Students’ L2 Reticence in English language learning. Linguist. Educ. 2021, 61, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.P.; Clément, R. A Chinese conceptualisation of willingness to communicate in ESL. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2003, 16, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.-M.; Dewaele, L. Learner-internal and learner-external predictors of willingness to communicate in the FL classroom. J. Eur. Second. Lang. Assoc. 2018, 2, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dewaele, J.-M. The effect of classroom emotions, attitudes toward English, and teacher behavior on willingness to communicate among English Foreign Language Learners. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 38, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Peng, A.; Patterson, M.M. The roles of class social climate, language mindset, and emotions in predicting willingness to communicate in a foreign language. System 2021, 99, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.M. Understanding Chinese learners’ willingness to communicate in a New Zealand ESL classroom: A multiple case study drawing on the theory of planned behavior. System 2013, 41, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N.; Tanbakooei, N. Willingness to communicate: Rise, development, and some future directions. Lang. Linguist. Compass 2016, 10, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiryousefi, M. Willingness to communicate, interest, motives to communicate with the instructor, and L2 speaking: A focus on the role of age and gender. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2018, 12, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Investigating situational willingness to communicate within second language classrooms from an ecological perspective. System 2011, 39, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, P.D.; Burns, C.; Jessome, A. Ambivalence about communicating in a second language: A qualitative study of French immersion students’ willingness to communicate. Mod. Lang. J. 2011, 95, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.E. Willingness to communicate in an L2 and integrative motivation among college students in an intensive English language program in China. Univ. Syd. Pap. TESOL 2007, 2, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zarrinabadi, N. Communicating in a second language: Investigating the effect of teacher on learners’ willingness to communicate. System 2014, 42, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, Z.; Rezazadeh, M.; Rahimi-Dashti, M. Teachers’ Immediacy, Self-disclosure, and Technology Policy as Predictors of Willingness to Communicate: A Structural Equational Modeling Analysis. In New Perspectives on Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language; Zarrinabadi, N., Pawlak, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey, J.C.; Baer, J.E. Willingness to Communicate: The Construct and Its Measurement. In Proceedings of the Paper Presented at the Annual Convention of the Speech Communication Association, Denver, CO, USA, 7–10 November 1985. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Dörnyei, Z.; Clément, R.; Noels, K.A. Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Mod. Lang. J. 1998, 82, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D. Willingness to communicate in the second language: Understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. Mod. Lang. J. 2007, 91, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J. Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System 2005, 33, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T.; MacIntyre, P.D.; Ikeda, M. Situated willingness to communicate in an L2: Interplay of individual characteristics and context. Lang. Teach. Res. 2018, 22, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munezane, Y. Enhancing willingness to communicate: Relative effects of visualization and goal setting. Mod. Lang. J. 2015, 99, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fushino, K. Causal relationships between communication confidence, beliefs about group work, and willingness to communicate in foreign language group work. TESOL Q. 2010, 44, 700–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonsooly, B.; Khajavy, G.H.; Asadpour, S.F. Willingness to communicate in English among Iranian non–English major university students. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 31, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T. Willingness to communicate in a second language: The Japanese EFL context. Mod. Lang. J. 2002, 86, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Philp, J. Interactional context and willingness to communicate: A comparison of behavior in whole class, group and dyadic interaction. System 2006, 34, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A. Investigating the dynamic nature of L2 willingness to communicate. System 2015, 50, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashima, T.; Ikeda, M.; Nakahira, S. Talk and silence in an EFL classroom: Interplay of learners and context. In The Dynamic Interplay between Context and the Language Learner; King, J., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 104–126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Beckmann, N.; Beckmann, J.F. To talk or not to talk: A review of situational antecedents of willingness to communicate in the second language classroom. System 2018, 72, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nematizadeh, S.; Wood, D. Second Language Willingness to Communicate as a Complex Dynamic System. In New Perspectives on Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language; Zarrinabadi, N., Pawlak, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. In Attitudes, Orientations, and Motivations in Language Learning; Dörnyei, Z., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, J.-M. On emotions in foreign language learning and use. Lang. Teach. 2015, 39, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taguchi, N. Cognition, language contact, and the development of pragmatic comprehension in a study-abroad context. Lang. Learn. 2008, 58, 33–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mystkowska-Wiertelak, A.; Pawlak, M. Willingness to Communicate in Instructed Second Language Acquisition; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, J. Western misperceptions of the Confucian-heritage learning culture. In The Chinese Learner: Cultural, Psychological and Contextual Influences; Watkins, D.A., Biggs, J.B., Eds.; Comparative Education Research Center: Hong Kong, China, 1996; pp. 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cortazzi, M.; Jin, L. Cultures of learning: Language classrooms in China. In Society and the Language Classroom; Coleman, H., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- de Saint Léger, D.; Storch, N. Learners’ perceptions and attitudes: Implications for willingness to communicate in an L2 classroom. System 2009, 37, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.R. Foreign language teaching in China: Problems and perspectives. Can. Int. Educ. 1987, 1, 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Walsh, S. ‘Seeing is believing’: Looking at EFL teachers’ beliefs through classroom interaction. Classr. Discourse 2011, 2, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Bourne, J. Intercultural Adaptation–It is a Two-Way Process: Examples from a British MBA Programme. In Researching Chinese Learners: Skills, Perceptions & Intercultural Adaptation; Jin, L., Cortazzi, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011; pp. 250–273. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, J.-M.; Comanaru, R.; Faraco, M. The affective benefits of a pre-sessional course at the start of study abroad. In Social Interaction, Identity and Language Learning during Residence Abroad; Mitchell, R., Tracy-Ventura, N., McManus, K., Eds.; Eurosla Monographs Series; The European Second Language Association: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q.; Maley, A. Changing places: A study of Chinese students in the UK. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 2008, 8, 224–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.E. L2 motivational self system, attitudes, and affect as predictors of L2 WTC: An imagined community perspective. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2015, 24, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Warden, C.A.; Chang, H.T. Motivators that do not motivate: The case of Chinese EFL learners and the influence of culture on motivation. TESOL Q. 2005, 39, 609–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durkin, K. The adaptation of East Asian masters students to western norms of critical thinking and argumentation in the UK. Intercult. Educ. 2008, 19, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durkin, K. Adapting to Western Norms of Critical Argumentation and Debate. In Researching Chinese Learners. Skills, Perceptions and Intercultural Adaptations; Jin, L., Cortazzi, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 274–291. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Topping, K.; Jindal-Snape, D. Intercultural adaptation of Chinese postgraduate students and their UK tutors. In Researching Chinese Learners: Skills, Perceptions & Intercultural Adaptation; Jin, L., Cortazzi, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011; pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, V.P. Teacher nonverbal immediacy: Uses and outcomes. In Communication for Teachers; Chesebro, J.L., McCroskey, J.C., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; McCormack, J. The influence of teachers. Phi Delta Kappa 1986, 67, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Effiong, O. Getting them speaking: Classroom social factors and Foreign Language Anxiety. TESOL J. 2016, 7, 132–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.A.; Belmont, M.J. Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. J. Educ. Psychol. 1993, 85, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assor, A.; Kaplan, H.; Roth, G. Choice is good, but relevance is excellent: Autonomy-enhancing and suppressing teacher behaviours predicting students’ engagement in schoolwork. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 72, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.P.; Wellborn, J.G. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In Self Processes and Development: Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology; Gunnar, M.R., Sroufe, L.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A.; Friedman, D. The impact of teacher immediacy on student participation: An objective cross-disciplinary examination. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 2013, 25, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, S. The relationship between teacher’s technology integration ability and usage. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2010, 43, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, R.; Dunn, K. Teaching Secondary Students through Their Individual Learning Styles: Practical Approaches for Grades 7–12; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, B. An exploration of speaking-in-class anxiety with Chinese ESL learners. System 2011, 39, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Z. Chinese students’ perceptions of native English-speaking teachers in EFL teaching. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2010, 31, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Oxford, R.L. A diary study focusing on listening and speaking: The evolving interaction of learning styles and learning strategies in a motivated, advanced ESL learner. System 2014, 43, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, M. Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J. Pluricentric Views towards English and Implications for ELT in China. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2015, 8, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kachru, B.B. World Englishes: Agony and ecstasy. J. Aesthetic Educ. 1996, 30, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.-M.; Bak, T.; Ortega, L. Why the mythical “native speaker” has mud on its face. In Changing Face of the "Native Speaker": Perspectives from Multilingualism and Globalization; Slavkov, N., Melo Pfeifer, S., Kerschhofer, N., Eds.; Mouton De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, S.L. English as an International Language. In The Cambridge Guide to Pedagogy and Practice in Second Language Teaching; Richards, J., Burns, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen, T.; MacIntyre, P.D. Capitalizing on Individual Differences: From Premise to Practice; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D. The idiodynamic method: A closer look at the dynamics of communication traits. Commun. Res. Rep. 2012, 29, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollon, S. Not to waste words or students. In Culture in Second Language Teaching and Learning; Hinkel, E., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Degen, T.; Absalom, D.; Australia, C. Teaching across cultures: Considerations for Western EFL teachers in China. Hong Kong J. Appl. Linguist. 1998, 3, 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Xing, J. Teachers’ perceived difficulty in implementing TBLT in China. In Contemporary Task-Based Language Teaching in Asia; Thomas, M., Reinders, H., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2015; pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.C.; Rodgers, T.S. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Baker, S.C.; Clément, R.; Conrod, S. Willingness to communicate, social support, and language-learning orientations of immersion students. Stud. Second. Lang. Acquis. 2001, 23, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashimoto, Y. Motivation and willingness to communicate as predictors of reported L2 use: The Japanese ESL context. Second Lang. Stud. 2002, 20, 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- Plonsky, L.; Ghanbar, H. Multiple regression in L2 research: A methodological synthesis and guide to interpreting R2 values. Mod. Lang. J. 2018, 102, 713–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roever, C.; Phakiti, A. Quantitative Methods for Second Language Research: A Problem-Solving Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gonulal, T. Investigating the potential of humour in EFL classrooms. Eur. J. Humour Res. 2018, 6, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Housen, A.; Janssens, S.; Pierrard, M. Frans en Engels als Vreemde Talen in Vlaamse Scholen. Een Vergelijkend Onderzoek [French and English as Foreign Languages in Flemish Schools. A Comparative Study]; VUB-Press: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D. Case Studies of Iranian Migrants’ WTC Within an Ecosystems Framework: The Influence of Past and Present Language Learning Experiences. In New Perspectives on Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language; Zarrinabadi, N., Pawlak, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.X. Bridging the gap between teaching styles and learning styles: A cross-cultural perspective. Teach. Engl. Second Foreign Lang. 2006, 10, n3. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Cortazzi, M. Researching Chinese Learners: Skills, Perceptions, Intercultural Adaptations; Palgrave-Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzer, M.B.; Frymier, A.B.; Irwin, J. An explanation of the relationship between instructor humour and student learning: Instructional humour processing theory. Commun. Educ. 2010, 59, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Cross-Linguistic and Cross-Cultural Humour Appreciation among Chinese L2 Users of English. Ph.D. Thesis, Birkbeck College, University of London, London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.S. Social orientation and individual modernity among Chinese students in Taiwan. J. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 113, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.E. The roles of multimodal pedagogic effects and classroom environment in willingness to communicate in English. System 2019, 82, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Dewaele, J.-M. What lies bubbling beneath the surface? A longitudinal perspective on fluctuations of ideal and Ought-to L2 self among Chinese learners of English. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 2015, 53, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Participants | Gender | Age | English Proficiency Level (Self-Reported) | Country of Study | Length of English Study (Domestic or Abroad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | Male | 24 | Intermediate | China | 12 years |

| Zhao | Male | 26 | High Intermediate | China | 14 years |

| Chen | Female | 23 | Low Intermediate | China | 11 years |

| Hao | Female | 23 | Intermediate | China | 11 years |

| Jia | Female | 25 | Intermediate | China | 13 years |

| Luo | Female | 26 | Advanced | USA, UK | 3 years |

| Zhang | Male | 24 | High Intermediate | UK | 2 years |

| Ding | Male | 21 | Intermediate | UK | 1 year |

| Domestic | Abroad | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | |

| Students’ attitudes towards teachers | 4.09 | 0.73 | 3.77 | 0.92 | 2.60 ** |

| Teacher’s age | 1.42 | 0.71 | 1.82 | 0.89 | −3.89 *** |

| Dressing style | 3.07 | 0.85 | 2.92 | 0.79 | 1.32 |

| Degree of strictness | 1.95 | 1.04 | 2.47 | 1.19 | −3.18 ** |

| Degree of friendliness | 4.45 | 0.56 | 4.26 | 0.83 | 1.95 |

| Joking | 3.2 | 0.62 | 3.36 | 0.63 | −1.73 |

| Showing concern | 3.71 | 0.82 | 3.48 | 0.80 | 1.98 |

| Enjoying interaction | 3.78 | 0.85 | 3.61 | 0.82 | 1.39 |

| Gesturing | 3.34 | 0.77 | 3.21 | 0.96 | 1.01 |

| Tone of voice | 4.03 | 0.98 | 3.44 | 0.76 | 4.56 *** |

| Body position | 4.17 | 0.98 | 3.45 | 0.91 | 5.23 *** |

| Physical distance | 3.29 | 0.78 | 3.15 | 0.61 | 1.44 |

| Frequency of using English | 3.91 | 0.56 | 4.79 | 0.50 | −11.45 *** |

| Time spent on writing (in %) | 18.36 | 11.36 | 18.01 | 7.55 | 0.25 |

| Time spent on reading (in %) | 39.39 | 16.22 | 19.83 | 9.69 | 10.58 *** |

| Time spent on listening (in %) | 23.52 | 12.41 | 18.62 | 8.73 | 3.19 ** |

| Time spent on speaking (in %) | 18.03 | 13.22 | 41.29 | 17.93 | −8.96 *** |

| Predictability | 3.45 | 0.88 | 3.32 | 0.80 | 1.14 |

| Domestic | Abroad | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 WTC Inside Classrooms | L2 WTC Outside Classrooms | L2 WTC Inside Classrooms | L2 WTC Outside Classrooms | |

| General attitude towards teachers | 0.369 ** | 0.282 * | 0.125 | 0.045 |

| Age | −0.129 | 0.003 | 0.319 | 0.254 |

| Dressing style | 0.343 ** | 0.190 | 0.006 | 0.059 |

| Degree of strictness | 0.114 | 0.054 | 0.044 | 0.120 |

| Degree of friendliness | 0.240 | 0.111 | 0.181 | 0.052 |

| Joking | −0.034 | 0.050 | 0.093 | −0.025 |

| Showing concern | 0.336 ** | 0.275* | 0.280 | 0.263 |

| Enjoying interaction | 0.267 * | 0.198 | 0.333 | 0.209 |

| Gesturing | 0.248 * | 0.045 | 443 ** | 0.222 |

| Tone of voice | 0.351 * | 0.232 | 0.343 | 0.118 |

| Body position | 0.164 | 0.081 | 0.097 | −0.006 |

| Physical distance | 0.171 | 0.097 | 0.240 | 0.194 |

| Frequency of using English | 0.148 | 0.167 | 0.094 | 0.153 |

| Time spent on writing | 0.175 | 0.227 | 0.179 | 0.204 |

| Time spent on reading | 0.060 | −0.030 | 0.177 | 0.239 |

| Time spent on listening | −0.014 | 0.003 | 0.280 | 0.381 |

| Time spent on speaking | 0.043 | 0.090 | −0.301 | −0.385 |

| Predictability of a class | 0.059 | 0.015 | −0.003 | 0.028 |

| Model | Β | t | p | Adjusted R Square | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 WTC inside classrooms | General attitude towards English teacher | 0.321 | 4.31 | 0.000 | 0.207 |

| Dressing style | 0.290 | 3.89 | 0.000 | ||

| L2 WTC outside classrooms | General attitude towards English teacher | 0.282 | 3.56 | 0.001 | 0.073 |

| China Group | Abroad Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| L2 WTC Inside Classrooms | Correlations | Students’ attitude towards teachers; Dressing style; Showing concern; Enjoying interaction; Gesturing; Tone of voice | Gesturing |

| Significant predictors | Students’ attitude towards teacher; Dressing style | ||

| L2 WTC Outside classrooms | Correlations | Students’ attitude towards teacher; Showing concern | |

| Significant predictors | Students’ attitude towards teacher | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Dewaele, J.-M.; Zhang, T. Sustainable Development of EFL/ESL Learners’ Willingness to Communicate: The Effects of Teachers and Teaching Styles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010396

Chen X, Dewaele J-M, Zhang T. Sustainable Development of EFL/ESL Learners’ Willingness to Communicate: The Effects of Teachers and Teaching Styles. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010396

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xuemei, Jean-Marc Dewaele, and Tiefu Zhang. 2022. "Sustainable Development of EFL/ESL Learners’ Willingness to Communicate: The Effects of Teachers and Teaching Styles" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010396

APA StyleChen, X., Dewaele, J.-M., & Zhang, T. (2022). Sustainable Development of EFL/ESL Learners’ Willingness to Communicate: The Effects of Teachers and Teaching Styles. Sustainability, 14(1), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010396