Abstract

Researchers indicate that employees with a high level of education tend to have better creative performance. However, few studies have investigated the boundary conditions of this association. The componential model of creativity demonstrates that both task-relevant skills and creativity-relevant skills are indispensable factors of creative performance. Job tenure, which generally hinders employees from acquiring creativity-relevant skills, is regarded as a potential boundary condition. In this study, we investigate how job tenure weakens positive influence of education on creative performance through task performance. Using a sample of 368 employees and 43 leaders in a provincial bank in China, we indeed find that job tenure negatively moderates the indirect relationship between education and creative performance via task performance. Specifically, the positive relationship is weakened when job tenure is high than when it is low. We also discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our study and highlight future research directions.

1. Introduction

Creative performance has become a valuable asset for employees and a kind of sustainable source for organization and it is critical for organization’s sustainable development in a dynamic environment [1,2]. The componential model of creativity articulates the process of individual creativity and emphasizes that task-relevant skills (i.e., task-relevant knowledge, technical skills, and special talents) and creativity-relevant skills (i.e., creative cognitive style and a heuristic exploration of new ideas) are indispensable factors in creative performance [3,4,5]. Prior research has shown that appropriate education and learning can improve employees’ creative performance [6,7,8], since task-relevant skills enhanced through education in the domain of endeavors can account for the improvement of creative performance according to the componential model of creativity [3,4,5]. However, merely a few studies have investigated the boundary conditions of this association. Therefore, the present study seeks to simultaneously consider the influence of both task- and creativity-relevant skills on creative performance. Specifically, job tenure, which generally hinders employees from acquiring creativity-relevant skills [9,10], is regarded as a potential boundary condition of the relationship between educational level and creative performance. This is because employees with high job tenures tend to increase their cognitive fixation and rely on previous experiences, and they are less willing to participate in training and development programs and lack the desire to create new products and methods, resulting in fewer creativity-relevant skills [9,11]. Employees with many task-relevant skills cannot achieve high creative performance if they lack creativity-relevant skills [3,5]. Therefore, this study has verified the common important effects of both task- and creativity-relevant skills on creative performance.

Although task-relevant skills can generate high creative performance, creativity-relevant skills are also a necessary component of creativity [3]. Therefore, this study seeks to investigate the critical factors that may heavily influence the acquisition of creativity-relevant skills. As job tenure increases, employees tend to rely on habitual thinking pathways or fail to abandon inappropriate problem-solving angles. Gradually, they are loath to explore creative working methods, which results in them developing a fixed mindset and cognition [9,12]. Additionally, when employees work in a position for an extended period, they, naturally, devote a great deal of time and energy to prior work approaches and experience; consequently, they strengthen their commitment of resources toward previous work decisions and methods, even if they are inappropriate [13,14]. The increase in job tenure tends to decrease flexibility, which results in a lack of creativity-relevant skills [3]. Especially for employees with high task performance, their fixed mindsets are further entrenched and their creative performance is low. Therefore, the current study considers job tenure as a critical factor that may influence the relationship between task performance and creative performance.

Few studies have tested the specific theoretical mechanism between educational level and creative performance. To bridge this research gap, the present study explores the theoretical mechanism on how educational level influences creative performance. Specifically, this study investigates how educational level positively affects creative performance through task performance according to the componential model of creativity [3,5]. Education is a kind of important human capital, and individuals can develop various professional skills and improve their productivity through a formal education system [7]. Then, employees will apply the acquired knowledge to their daily work, so they can complete assigned tasks adequately and efficiently, and improve their task performance. Moreover, education can cultivate critical thinking, which improves the employees’ ability to solve problems and acquire cognitive skills, resulting in the increase of task-relevant skills and improvement of task performance [15]. The componential model of creativity demonstrates that task-relevant skills contribute to high creative performance [3]. Thus, creative performance is expected to improve through the increase of educational level mediated by task performance.

In sum, this study seeks to uncover the relationship between educational level and creative performance through the theoretical mechanism of task performance and explore the boundary condition of job tenure. The present study has at least three contributions. First, by integrating the componential model of creativity, we explain how educational level influences creative performance through task performance and verify the moderating role of job tenure. By testing this model, we emphasize that both task-relevant skills and creativity-relevant skills are emphasized as important factors influencing creative performance and contribute to the research literature about creative performance. Second, our research results also contribute to the further understanding and development of the componential model of creativity by studying the theoretical mechanism of task performance. We indicate that education, as an important human capital, may increase employees’ creative performance through basic task performance. Third, this study tests the boundary condition of the educational level–creative performance link by showing that job tenure, which can influence employees’ creativity-relevant skills, affects the relationship between educational level and creative performance.

2. Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Componential Model of Creativity

The componential model of creativity articulates the process of individual creativity and emphasizes that there are two kinds of important skills that employees need to increase their creative performance [3]. The critical components of creativity include both task-relevant skills (called “skills in the task domain”) and creativity-relevant skills (called “skills in creative thinking”) [3,5]. Specifically, task-relevant knowledge, technical skills, and special talents belong to task-relevant skills, which employees use to solve a given problem or to do a task. Similarly, creativity-relevant skills, which include creative cognitive style and a heuristic exploration of new ideas, are indispensable for producing creative work [3]. Task-relevant skills are seen as raw materials available for creativity and they are the essential elements to do creative work in the task domain [3,5,16]. However, excellent task-relevant skills alone are insufficient for employees to create new ideas and products. Creativity-relevant skills are seen as an executive controller [3], so they are also an indispensable element for creative work. Only with this kind of skills can employees generate useful and novel ideas [3]. The higher the level of the two skills (i.e., task-relevant skills and creativity-relevant skills) that employees acquire, the greater the employees’ overall creative performance should be [3].

2.2. Educational Level and Task Performance

Task performance refers to employees’ contribution to the core technology of the organization, directly through production activities and indirectly providing materials or services [17]. It is an important dimension of work performance [18] and is measured according to the degree of goals accomplished based on formal job descriptions [19,20]. Employees transform the raw resources into products and services and invent technology through task performance [21].

Concerning education, the intention of being educated is to acquire knowledge, develop rationality, and reflect social values, and education is seen as a practical social activity [22,23]. Individuals obtain certificates for formal school completion, approved by an educational administrative department, and the highest degree of education obtained represents their educational level. Education is seen as a kind of human capital, which is a crucial input for creativity, research, and development activities [7]. Educational level is closely related to employees’ productivity and performance [24]. Through receiving education, employees can improve their cognitive level, gain appropriate knowledge, and accumulate production skills [25,26]. Employees can then apply the knowledge and skills they have acquired to their daily work, so they can complete assigned tasks adequately and efficiently, and fulfill their work responsibilities. Thus, we expect an increase in educational level to improve their task performance, and propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Educational level is positively related to task performance.

2.3. The Mediating Role of Task Performance

Creative performance is an important factor of organization production and competitiveness [27,28]. It can be conceived as an advantage for sustainable development [20], and consequently, it receives increased attention from companies, especially high-tech firms. Creative performance can be defined as the generation and implementation of innovative and meaningful ideas by individuals or a group of people, incorporating proposing innovating ideas, finding adequate ways to solve problems, and producing original contributions [29,30]. To improve creative performance, individuals or organizations need to abandon established working methods and develop creative solutions and products [31].

High task performance may indicate that employees have some relevant skills in the task domain and can complete tasks adequately and effectively [3,5]. In addition, the employees with high task performance generally get more support from the environment. For example, they can gain their leader’s attention and acquire more training and work opportunities, resulting in further improvement of their task-relevant skills [32]. According to the componential model of creativity, task-relevant skills are an essential component of creative work [3]. They are seen as “raw materials”, the basis for any creative performance [5]. Employees who secure high task performance ratings generally have plenty of task-relevant skills and they tend to seek more technical skills and task-relevant knowledge, thus further producing creative ideas and work, finally leading to high creative performance. Moreover, high performance brings employees good job satisfaction, which indicates they have good feelings in prior work experience, so they will devote more to creative work [33]. Therefore, we posit that task performance positively affects creative performance and propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Task performance is positively related to creative performance.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Task performance mediates the positive relationship between educational level and creative performance.

2.4. The Moderating Role of Job Tenure

Previous studies indicate that job tenure is an impeding factor of creativity-relevant skills [9,12]. Job tenure also influences the relationship between task performance and creative performance, mainly for two reasons. First, when employees work in one position for an extend period of time, they rely on habitual thinking pathways and be loath to explore creativity working methods [12]. The increase of job tenure tends to decrease their flexibility, which results in a lack of creativity-relevant skills [3]. Especially for employees with high task performance, they tend to rely more on their previous successful experiences. Subsequently, as their working time extends, they become unlikely to change their previous working patterns and less willing to acquire creativity-relevant skills. Creativity-relevant skills are a necessary component of creative performance since creativity-relevant skills act as an executive controller and determine how to explore cognition flexibly and solve problems creatively [3]. Thus, job tenure weakens the positive relationship between task performance and creative performance. Additionally, when employees work in one position for a relatively long time, they are satisfied with their own working patterns, they will summarize previous work experience and rely on this work knowledge and these thinking habits and are unwilling to create new working methods or develop creativity-relevant skills. Gradually, the employees with high job tenure will develop cognitive fixation and fixed mindsets, resulting in less motivation and the ability to be creative [9,12]. Therefore, the longer the job tenure, the lower the probability that employees with high task performance will have high creative performance.

In contrast, employees with low job tenure are more active in exploring new work approaches and creative process. High task performance employees, in particular, tend to have a strong motivation to learn and create new patterns, which develops their creative mindset [34]. Employees with creative mindset are more willing to accomplish creative tasks and have high cognitive flexibility, which results in their high creative performance [3]. Therefore, the positive relationship between task performance and creative performance is enhanced for employees with low job tenure. In summary, we propose that the longer the job tenure is, the less likely task performance will positively lead to creative performance. Hypothesis 4 is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Job tenure negatively moderates the relationship between task performance and creative performance, such that the positive relation is weaker when job tenure is higher.

In sum, because we have argued that task performance mediates the positive relationship between educational level and creative performance, and that job tenure negatively moderates the extent to which task performance affects creative performance, we further propose the following conditional indirect relationship. The mediating effect of task performance will be weakened when employees have higher job tenure. Thus, Hypothesis 5 is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Job tenure negatively moderates the strength of mediated relationship between educational level and creative performance via task performance. That is, the relationship will be weakened when job tenure is high than when it is low.

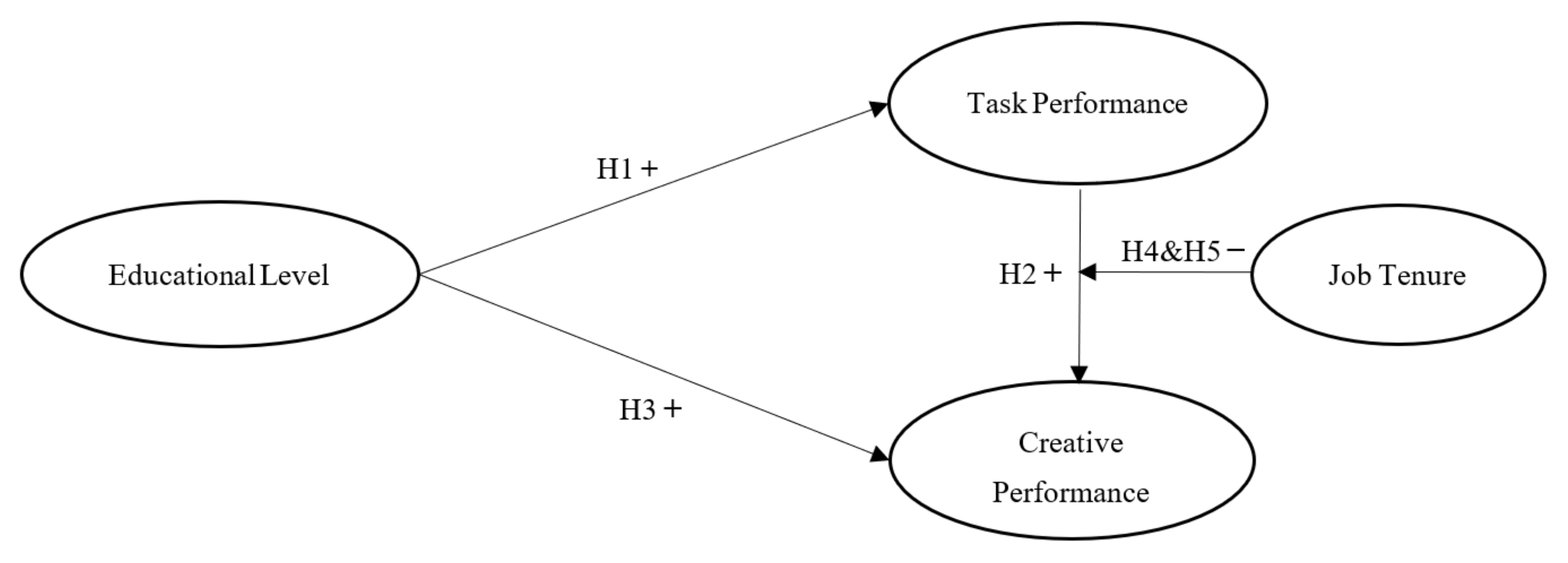

We therefore developed a moderated mediation model by combining Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed theoretical model.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Setting and Sample Descriptions

We conducted this study in a provincial bank in China. Research participants consisted of 380 employees of various ages from 43 sub-branches who accepted our survey. One of the authors of this study was on-site to distribute and collect the questionnaires. The data were collected from two sources: the employees and their immediate leaders. Employees reported their own educational level and job tenure, and leaders rated the followers’ task performance and creative performance. We collected the data in two different time periods. At Time 1, employee demographic information (i.e., age and gender), educational level, and job tenure were collected; at Time 2 after a month, leaders rated their followers’ task performance and creative performance. Ultimately, we retained the sample of 368 employees and 43 leaders after deleting the questionnaires with incomplete information, yielding a 97% overall response rate. Demographic data were provided by the human resources department of the bank before the formal survey was distributed. All respondents were informed that their information would be treated with strict confidentiality and that they had the right to withdraw from the survey at any time.

The 380 employees were separated into 43 work groups, each with an average of 8.84 individuals. Among them, 79.4% of participants were female and the average age of participants was 29.96 years (SD = 7.17). The size of the groups ranged from 4 to 21, which fits the standard of working groups set by [35] of between 3 and 50 participants.

3.2. Measures

All measurement items were used in prior studies and were originally drafted in English. The items were then back-translated to ensure accuracy [36]. Our analysis produced four factors: educational level, task performance, job tenure, and creative performance.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

3.3.1. Educational Level

Educational level refers to the highest degree of education that an individual has received from a formal school. Individuals receive certificates of formal school approved by the educational administrative department. We divided the educational level into three degrees: less than a Bachelor’s degree, Bachelor’s degree, and Master’s degree or above. Employees rated their own educational level on a three-point scale (1 = less than a Bachelor’s degree, 2 = Bachelor’s degree, and 3 = Master’s degree or above). Results showed that most employees had a Bachelor’s degree (87.1%), while 12.1% had less than a Bachelor’s degree, and 0.8% had a Master’s degree or above.

3.3.2. Task Performance

This study adapted Williams and Anderson’s [37] measurement scale to assess task performance. Sample items included, “The employee adequately completes assigned duties”. The employee fulfills responsibilities specified in the job description.” Each item was scored on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 7 = “totally agree”. Cronbach’s α for task performance was 0.91.

3.3.3. Job Tenure

Employees wrote down the number of years they had been working in their current position. Job tenure ranged from 1 to 36 years.

3.3.4. Creative Performance

To assess creative performance, we adapted Zhou’s [30] measurement to make it suitable for the workplace in China. We retained four important items and the measurement was more applicable. The employees’ creative performance was rated by their immediate leaders. Sample items included, “The employee is the first to try new ideas or solutions”. and “The employee comes up with creative solutions to problems”. Each item was scored on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “totally disagree” to 7 = “totally agree”. Cronbach’s α for creative performance was 0.94.

3.3.5. Control Variables

The demographic variables of the employees included age, gender (1 = male, 2 = female), educational level, and job tenure. Demographic variables (i.e., age and gender) were assigned as control variables. Specifically, age is related to one’s accumulated work experience and thus can influence his/her performance [38]. As men generally receive better performance evaluations from their supervisors than women [39], we also controlled for gender.

3.4. Data Analysis

Prior to testing the hypotheses, we initially used MPLUS 8.3 and did confirmatory factor analysis to rate the discriminant validity of the key variables in this study [40]. The two-factor model (i.e., task performance and creative performance) exhibited an adequate fit to the data. χ2 (25) = 105.00, standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) = 0.03, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.11, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.97, and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.96. Thereafter, we combined task performance and creative performance into one variable to form a one-factor model. χ2 (24) = 397.03, SRMR = 0.06, RMSEA = 0.22, CFI = 0.88, and TLI = 0.83. The results showed that the two-factor model was better, indicating that the two constructs had good discriminant validity.

4. Analytic Strategy and Results

Descriptive analyses and correlations between each pair of variables are presented in Table 1. We then employed hierarchical regressions to test the proposed hypotheses, and the results are shown in Table 2. Hypothesis 1 predicted a positive relationship between educational level and task performance, and the results in Table 2 Model 1 show that the positive coefficient was marginally significant (β = 0.33, p = 0.09). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

Table 1.

Mean, SD, and correlations of main variables.

Table 2.

Regression results for moderated mediation model.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that task performance was positively related to creative performance, and the results in Table 2 Model 3 show that the coefficient was significant and positive (β = 0.80, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3 predicted that task performance mediated the positive relationship between educational level and creative performance. We used SPSS-PROCESS to confirm the indirect effect of educational level on creative performance via task performance. The results showed that with a formal two-tailed significance test, the completely standardized indirect effect was significant (β = 0.07, 95% CI = (0.01, 0.14)). Hypothesis 3 was thus supported.

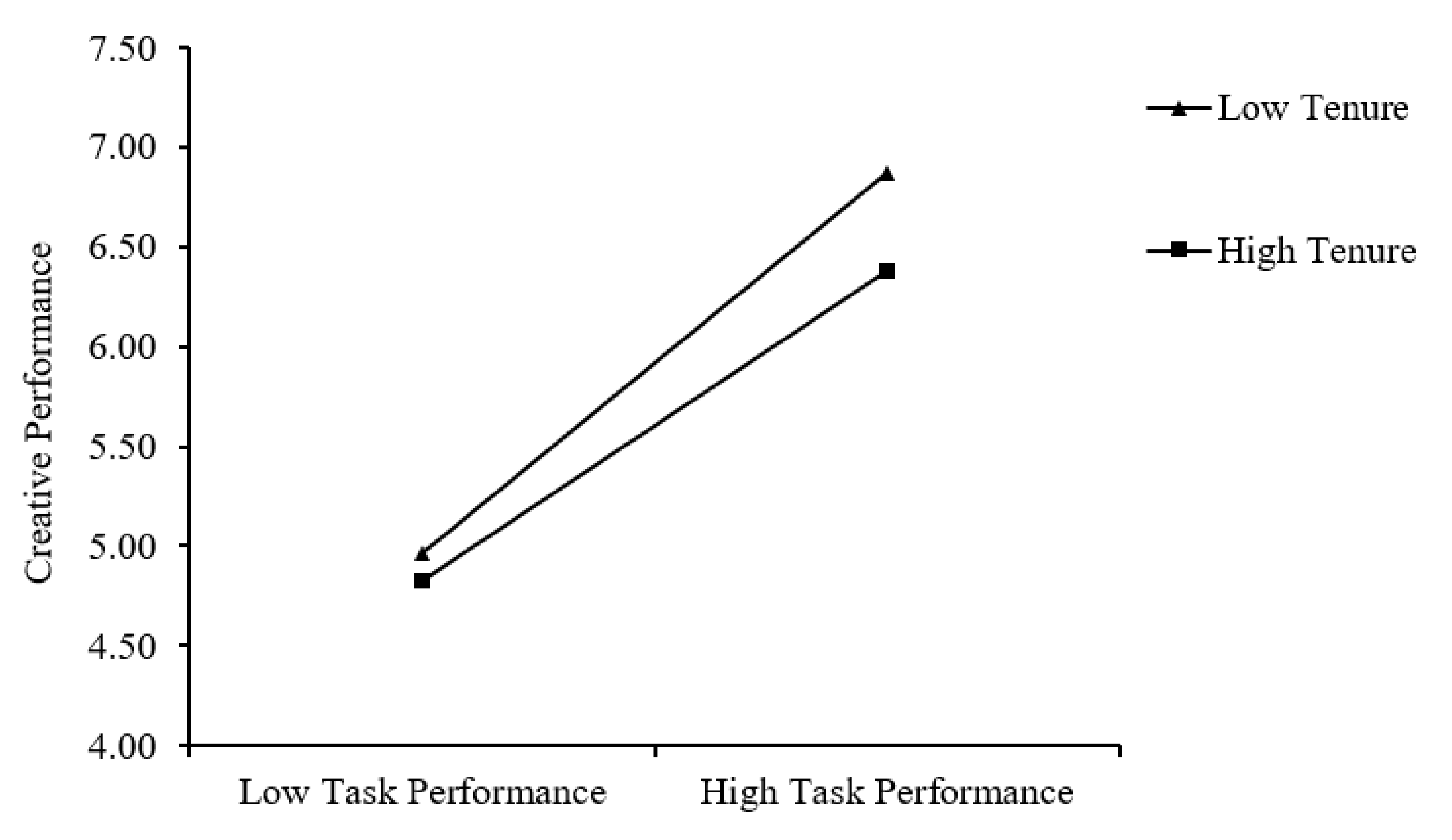

Hypothesis 4 predicted that job tenure negatively moderated the relationship between task performance and creative performance, such that the positive relationship was weaker when job tenure was higher. We used SPSS-PROCESS and derived 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to test our moderated hypothesis and research question. From Model 3 in Table 2, we found that the coefficient of task performance and creative performance was significant and positive (β = 0.80, p < 0.001), suggesting that task performance positively impacted creativity performance. The interaction effect between task performance and job tenure was significant (β = −0.02, p = 0.05), as shown in Model 4 of Table 2. At lower levels of job tenure, task performance had a significant effect on creative performance (Effect = 0.85, t = 20.34, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.77, 0.93)). At higher levels of job tenure, the positive effect of task performance on creative performance is weakened (Effect = 0.74, t = 16.51, p < 0.001, 95% CI = (0.65, 0.83)). The results indicate that with a lower level of job tenure, the positive effect of task performance on creative performance is larger, which means that job tenure weakens the positive relationship between task performance and creative performance. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported. Figure 2 shows the interaction effect of task performance and job tenure on creative performance.

Figure 2.

Job tenure moderates the relationship between task performance and creative performance.

Hypothesis 5 predicted that job tenure negatively moderated the strength of the mediated relationship between educational level and creative performance via task performance. Namely, the relationship is weaker when job tenure is high than when it is low. Based on the moderated mediation model described by Preacher et al. [41] and Hayes [42], we used the sample mean and mean ± 1 SD to distinguish the different levels of job tenure and conducted a bootstrapping test. We utilized a bootstrap sample of 5000 and the result is shown in Table 3. Under the 95% confidence interval, job tenure moderated the mediation effect of task performance on the relation between educational level and creative performance, thus indicating that the moderated mediation model was significant. Hence, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Table 3.

PROCESS results for moderated mediation model.

5. Discussion

Applying the componential model of creativity, we find that educational level is positively related to creative performance via task performance and job tenure can weaken this positive relationship. This indicates that employees’ job tenure can mitigate the positive effect of educational level on creative performance, such that the positive relationship between educational level and creative performance becomes weaker as employees’ job tenure gets longer.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, our primary contribution is the emphasis on the combined effects of multiple skills on creative performance. Prior research demonstrated the positive effect of every kind of skill on creativity respectively [3]. However, our research verifies that only one component such as task-relevant skills may not lead to high creative performance. Even if employees have many task-relevant skills, they cannot produce creative work when they lack creativity-relevant skills. This is because creative performance is improved by novel ideas and appropriate solutions to open-ended tasks [43]. Task-relevant skills are seen as raw materials for creativity, but creativity-relevant skills act as an executive controller and determine how to explore cognition flexibly and solve problems creatively [3]. Our findings verify and deepen the componential model of creativity.

Second, as we mentioned that combined effects of task- and creativity-relevant skills on creative performance should not be ignored, this study proposes a boundary condition of educational level-creative performance link by demonstrating that job tenure can mitigate the positive relationship between educational level and creative performance via task performance. When employees with high task performance work in one position for a relatively long time, they rely on their previous successful experience and tend to have fixed mindset [12] and cognitive fixation [9], and these employees will be loath to acquire creativity-relevant skills. Creative work cannot be produced when creativity-relevant skills are lacking [3]. Thus, job tenure may weaken the relationship between task performance and creative performance. In contrast, employees with low job tenure are more active in exploring new work approaches and creative processes, especially for high task performance employees [31]. Therefore, the positive relationship between task performance and creative performance will be strengthened at low level of job tenure.

Third, our study contributes to the theoretical understanding of improvement of employees’ task performance via which educational level connects with creative performance. Previous research concentrated on studying the antecedents of task performance, while we incorporate task performance as a mediator and investigate how educational level predicts creative performance through it. Education helps individuals accumulate work-related knowledge, improve production skills, and support fulfillment of main tasks, so their task performance can be improved through the increase of educational level [21,22,23,44]. As mentioned earlier, employees with high task performance generally receive their leader’s attention and gain more training opportunities, which results in further improvement of their task-relevant skills. The componential model of creativity demonstrated that task-relevant skills are a major component of creativity [3]. Thus, task performance can be a mediator linking educational level to creative performance.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study also offers some important practical insights. First, for the high-technology companies, recruiting new staff with high educational level is a good way to improve organizational performance. Such employees are likely to have more task-relevant skills and are able to complete work more efficiently and effectively, thus resulting in high task performance. Additionally, when these employees with high educational level join in a company and work in the position for a relatively short time, they more actively explore new ideas and creative solutions and tend to have a creative mindset [31], which may result in high creative performance [45].

Second, for leaders, they may need to provide employees who have long job tenure with more learning opportunities and cultivate team creative culture. Our research results show that educational level positively affects creative performance, but job tenure weakens their positive relationship. Moreover, employees’ creative behavior is affected by organizational creative culture and external environment [46]. Therefore, in the companies where development depends on high creativity, leaders should not only hire the employees with high educational level, but also cultivate creative team climate and encourage team members to invent innovative products and technologies. Furthermore, as employee job tenure becomes longer, employees tend to have a more fixed mindset, especially for those with high task performance. Therefore, leaders need to offer more training opportunities to improve these employees’ creativity-relevant skills and help employees to shift their mindset from fixed to creative [31].

Third, if employees receive a high level of education and acquire sufficient task-relevant knowledge and production skills, they can generally achieve high task performance. However, these employees may not produce creative work or achieve high creative performance when they lack creativity-relevant skills, especially when their job tenure becomes longer. To improve employees’ competitiveness and integrated performance, they need to develop a creative mindset and learn continuously. Moreover, employees should not rely solely on previous work experience, but keep exploring new ideas and approaches. Through this, they can attain numerous task and creativity-relevant skills and achieve both high task and creative performance.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study achieved valuable results, there are some limitations worth noting. First, the sample was confined to the financial industry, so the research findings are not widely representative and may not be generalizable to other fields. Different industries place different emphases on education and creative performance, and employees’ educational levels in different industries may also vary. The study of different samples may draw different conclusions. Therefore, further research should enlarge the sample size and include data from other industries.

Second, our research is based on a survey and there are some limitations in concluding a causal relationship between the main variables from the current study. Future studies can design an experiment to further support these hypotheses and improve the precision of research methods.

Third, the correlation coefficient between task performance and creative performance was not ideal, because both kinds of performance belong to different dimensions of performance. Moreover, task performance and creative performance were rated only by leaders in one time period, which may also have resulted in the high correlation coefficient. Therefore, future studies can try collecting the data from various sources (i.e., employees and leaders) and in two time periods.

Fourth, Hypothesis 1 predicted the positive relationship between educational level and task performance, and the regression result showed the coefficient was marginally significant. Our data collection process may account for this imperfect result. Specifically, the data was collected in two different time periods and from various sources (i.e., employees and leaders). Future researchers can design an experiment to further verify the relationship between educational level and task performance.

Fifth, the componential model of creativity articulates that task-relevant skills, creativity-relevant skills, and intrinsic motivation to do the task contribute to creative performance [3,5]. This study only explores the combined effect of two components (i.e., task-relevant skills and creativity-relevant skills) on creative performance. Therefore, the influence of intrinsic motivation on creative performance can be investigated in future studies.

Sixth, this paper studies a moderated mediation model and finds job tenure negatively moderates the strength of mediated relationship between educational level and creative performance via task performance. Other mediation mechanism and boundary conditions should be explored. For example, Shin et al. [17] studied the mechanism of task performance and creative performance at the team level. Future research can consider the variables at team level as the mediator or moderator to promote the research of task performance and creative performance.

Finally, our data were collected in China, and cultural differences that may also affect the generalizability of the findings have not been considered. To ensure external validity, future scholars should expand the sample to include other countries and conduct cross-national research.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, by integrating the componential model of creativity, the present study finds that job tenure weakens the positive influence of educational level on creative performance through task performance. Specifically, the positive relationship is weakened when job tenure is high than when it is low. We emphasize the importance of both task-relevant skills and creativity-relevant skills for creative performance, and find the boundary condition and theoretical mechanism of the educational level–creative performance link. These findings enrich the relevant research literature and have important managerial and practical implications.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the research concepts and design. L.Y. drafted the manuscript and performed data analysis. J.W. predominantly contributed to the data acquisition. L.Y. and J.Z. repeatedly revised and refined the content of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by ethical committee of the University of Science and Technology Beijing.

Informed Consent Statement

The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rese, A.; Kopplin, C.S.; Nielebock, C. Factors influencing members’ knowledge sharing and creative performance in coworking spaces. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2327–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative self-efficacy development and creative performance over time. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amabile, T.M. A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Cummings, B.S., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1988; pp. 123–167. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Gryskiewicz, S.S. Creativity in the R and D Laboratory; Technical Report Number 30; Center for Creative Managership: Greensboro, NC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.B. Employees’ online-based education and training program and creative performance: 3-way interaction effects of creative self-efficacy and perceived organizational support. Korean J. Resour. Dev. 2020, 23, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, D.A.; Okemakinde, T. Human capital theory: Implications for educational development. Pak. J. Soc. Sci. 2008, 24, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Shafait, Z.; Yumin, Z.; Meyer, N.; Sroka, W. Emotional intelligence, knowledge management processes and creative performance: Modelling the mediating role of self-directed learning in higher education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G.; Akinola, M.; Mason, M.F. “Switching on” creativity: Task switching can increase creativity by reducing cognitive fixation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2017, 139, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.; Maurer, T.J.; Barbeite, F.G.; Weiss, E.M.; Lippstreu, M. New measures of stereotypical beliefs about older workers’ ability and desire for development: Exploration among employees age 40 and over. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 95–418. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.; Feldman, D.C. The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Penguin Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Staw, B.M. Knee-deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perf. 1976, 16, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, M.L.; Deghetto, K.; Ketchen, D.J.; Combs, J.G. The impact of hiring directors’ choice-supportive bias and escalation of commitment on CEO compensation and dismissal following poor performance: A multimethod study. Strat. Manag. J. 2019, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, H.; Toom, A. Developing a performance assessment task in the Finnish higher education context: Conceptual and empirical insights. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 89, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, G.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Zhou, J. A cross-level perspective on employee creativity: Goal orientation, team learning behavior, and individual creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Pearse, J.L.; Porter, L.W.; Tripoli, A.L. Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: Does investment in employees pay off? Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 1089–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welbourne, T.M.; Johnson, D.E.; Erez, A. The role-based performance scale: Validity analysis of a theory-based measure. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 540–555. [Google Scholar]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In Personnel Selection in Organizations; Schmitt, N., Borman, W.C., Eds.; San Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, M.; Choi, J.N.; Lee, S.H. Does team culture matter? Roles of team culture and collective regulatory focus in team task and creative performance. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 41, 232–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basit, A.A. Examining how respectful engagement affects task performance and affective organizational commitment: The role of job engagement. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccia, E.S. The concept of education. Stud. Philos. Educ. 1968, 6, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitinski, M. The concept of education. Methodol. Rev. 2005, 12, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, B. Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Q. J. Econ. 1991, 106, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Babalola, J.B. Budget preparation and expenditure control in education. In Basic Text in Educational Planning; Babalola, J.B., Ed.; Ibadan Awemark Industrial Printers: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in Human Capital; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.; Chiang, H.; Lin, A. Helping behaviors convert negative affect into job satisfaction and creative performance: The moderating role of work competence. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1530–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hora, S.; Lemoine, G.J.; Xu, N.; Shalley, C.E. Unlocking and closing the gender gap in creative performance: A multilevel model. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris, B.; Shalini, K. Rewards and creative performance: A meta-analytic test of theoretically derived hypotheses. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 138, 809–830. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C.E.; Zhou, J.; Oldham, G.R. The effects of personal and contextual characteristics on creativity: Where should we go from here? J. Manag. 2004, 30, 933–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, W.; Fehr, R.; Yam, K.C.; Long, L.R.; Hao, P. Interactional justice, leader–member exchange, and employee performance: Examining the moderating role of justice differentiation. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Fayzullaev, A.K.U.; Dedahanov, A.T. Management characteristics as determinants of employee creativity: The mediating role of employee job satisfaction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, X.; Dust, S.B.; Direnzo, M.S.; Wang, S. Negative creativity in leader-follower relations: A daily investigation of leaders’ creative mindset, moral disengagement, and abusive supervision. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Joshi, A. Work team diversity. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Building and Developing the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 651–686. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship behavior and in-role behavior. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirom, A.; Shechter, G.S.; Fried, Y.; Cooper, C.L. Gender, age and tenure as moderators of work-related stressors’ relationships with job performance: A meta-analysis. Hum. Rel. 2008, 61, 1371–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, M.B.; Kaplan, S.; Brief, A.P.; Shull, A.; Dietz, J.; Mansfield, M.T.; Cohen, R. Does it pay to be a sexist? The relationship between modern sexism and career outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 69, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, C. Mplus User’s Guide: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables (version 8). In Proceedings of the 2017 19th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Girona, Spain, 2–6 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. J. Educ. Meas. 2013, 51, 335–337. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S. Cultural brokerage and creative performance in multicultural teams. Organ. Sci. 2017, 28, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Starchoň, P.; Lorincová, S.; Caha, Z. Education as a key in career building. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 1065–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P.; Farmer, S.M. Creative Self-Efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Stacho, Z.; Potkány, M.; Stachová, K.; Marcineková, K. The organizational culture as a support of innovation process’ management: A case study. Inter. J. Qual. Res. 2016, 10, 769–784. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).